Anatomy of a goal

How Leeds employed a narrow 4-3-3 to limit Arsenal's control of the half-spaces, and how Arsenal responded to make it a brace for Jesus

Arsenal scored their third goal against Leeds in the 55th minute, but it originated much earlier.

When preparing to face this Arsenal side, one of the primary challenges for opposing managers is how to contain and neutralize the half-spaces. So much of the Arsenal threat is generated through the dialogue of the wide areas (generally the wingers) and those to the inside of them (generally one of the “twin 8’s” — Ødegaard and Xhaka — or a freelancing striker). If you’re able to cut off that lifeblood, as Everton did, things suddenly look less dynamic.

For Arteta’s side, the half-space plays a primary role in preparations.

To help explain, here’s a graphic I made in haste. On the left diagram, you’ll see a “traditional” way of looking at the football pitch — the pitch is divided into 18 zones, and much of the focus is on exploiting “Zone 14,” where so many attacks originate:

On the right, however, you’ll see an evolution of that in the form of a positional, 20-zone layout. Pep Guardiola often gets the credit for the implementation of this system, but I don’t know the history well enough to say whether that’s true or not (and suspect he’s probably getting into Shakespeare-of-football territory where he’s a magnet for citations, both true and apocryphal).

What is true is that his teams have implemented this way of looking at the pitch to devastating effect. The bishops and queens of his chess boards — think Messi, Müller, or KDB — exploit this space by maximizing the amount of options they have to attack, and forcing defenders into bad situations.

Arteta has his own bishop — or should I say bish∅p? — and also focuses on control of this area. In a delightfully forensic piece for the Athletic, Liam Tharme and James McNicholas went through YouTube clips and All or Nothing footage to better understand the shrouded world of Arsenal training.

As you’ll see, the pitch is marked up to focus on the half-spaces:

This isn’t particularly unique in today’s game. But given Arsenal’s pure skill and relentless drilling, it has been uniquely impactful.

So how do teams try to defend against this? Generally speaking, one of two ways.

Some managers opt to double-team the wingers out wide. This serves a dual-purpose, the first obvious: it makes it harder for Saka and Martinelli to be successful in isolation, because it’s not a 1v1 — it’s a 1v2 (or in Saka’s case, a 1v3 … or a 1v4).

The other purpose is that it serves to effectively create a wall between the winger and the half-space. Joelinton and Dan Burn, for example, tried to cut off passes between Saka and Ødegaard. It generally worked, resulting in scoreless draw:

At Goodison Park, Dyche also threw multiple players at the wide wingers, isolating them and forcing them down the touchline, in what was probably Martinelli’s worst performance of the year:

This strategy has been less successful since Trossard’s introduction to the striker role, which preceded the return of Jesus — both of which have generally “unstuck” the wide areas amidst increasing defensive support.

Since then, opposing managers have been looking elsewhere.

That brings up option #2. Of late, that’s taken the form of man-marking the players in the half-spaces, and most specifically, assigning a player to rabidly follow Ødegaard around.

At Craven Cottage, Lukić looked to match the skipper’s movements as best he could, often shadow- or front-marking him to block passing lanes in his direction. I don’t feel like going through all that tape again, so here’s a screenshot I have on file that kinda shows it:

You’ve heard Ødegaard described as a “controller,” or the heartbeat of the team, and this is a move to counter that strength. There was a qualitative difference there that ultimately prevailed, but the idea was sound: take away the controller’s impact in the half-space, take away the control.

This is the route that Javi Gracia ultimately chose for Leeds.

The challenge

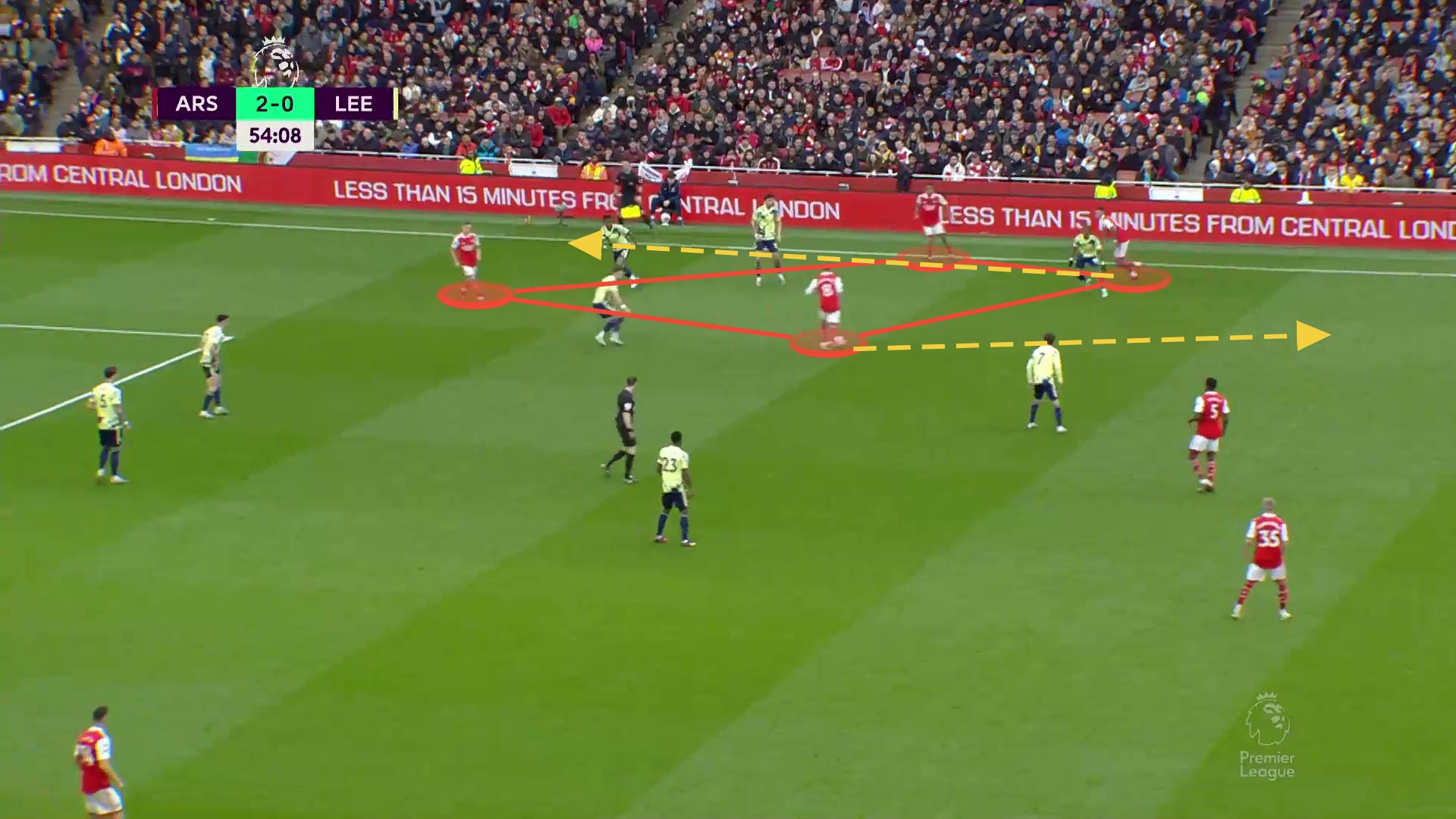

Potentially saving some players for the pivotal relegation fights ahead (including against Forest later today), the newish gaffer opted for a surprising lineup, seemingly featuring too many full-backs (4, if you include Struijk) and too few strikers (0). In the hour before kickoff, I thought it probably pointed to a 5-4-1 parked bus situation, but that’s not ultimately what unfolded.

Instead, it was a narrow 4-3-3, with extra attention on the half-space: big full-back Rasmus Kristensen tucked in as a midfielder, often following Xhaka around, and pivotally, CAM/winger Jack Harrison dropped back into an LCM spot.

With similar physicality and speed to Ødegaard, Harrison’s role wasn’t to stand in a zone, but to make life difficult for the captain — following him as closely as possible whenever he was moving around on the attacking right.

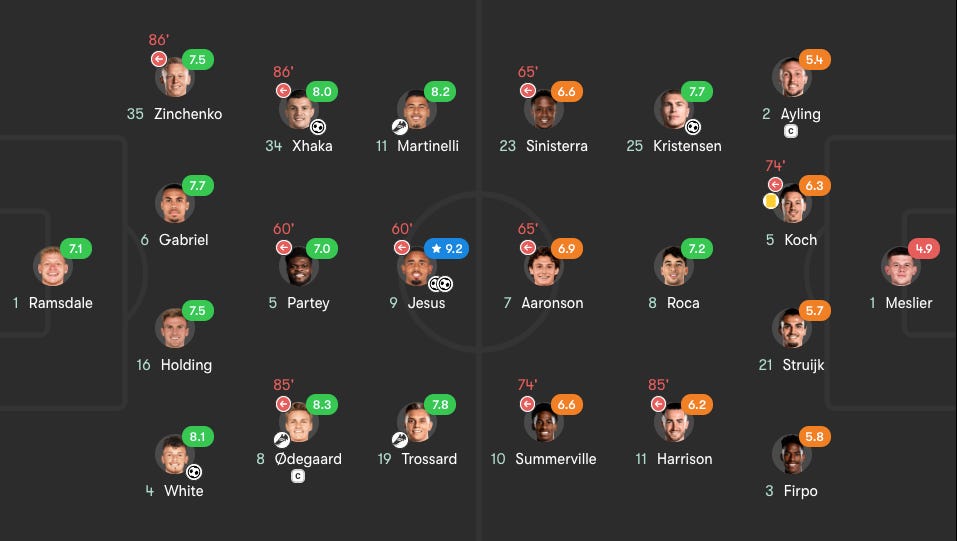

In practice, it looked like this. At 16’, Harrison followed Ødegaard all the way down to a back-5. Up top, you’ll see Kristensen following Xhaka as well:

…upon Ø receiving the pass, Harrison then immediately ran up to put pressure on his back, forcing Ødegaard to give it up to Trossard out wide. (For a later point, look how big of a gap there is between this right triangle and the other three attacking players up top):

…then, when Ødegaard got it back, Harrison trailed him all the way here:

Ødegaard recognized this all immediately, as he does. Within seven minutes, he was trying to drag Harrison around and create space behind for others.

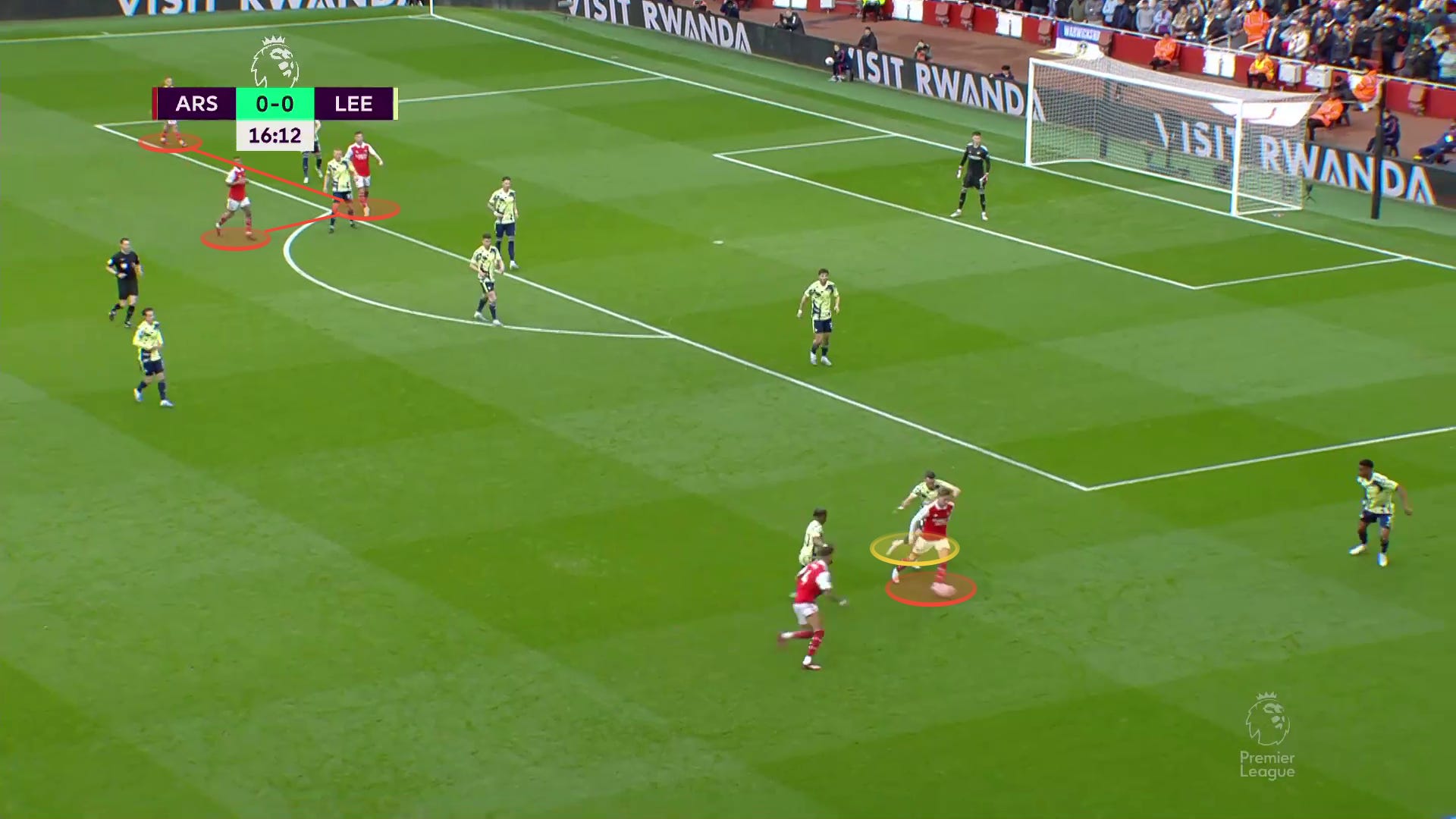

In a later moment, at 38’, he sprinted through the middle to drag Harrison up, and then ran across the pitch to force Harrison to hand him off to others, including Roca:

With Jesus so often hanging out left, this created a lot of situations like this in the first half — with the objective being to create wide overloads on the left:

To give you a sense of how left-leaning the attack generally was, here’s a map of Jesus’ received passes in the first half:

He wasn’t completely absent from the other side, but ultimately never really got involved in linking things up over there.

So with Jesus naturally floating left, and Ødegaard increasingly moving left to escape Harrison (without somebody necessarily backfilling his spot), there was nobody consistently challenging the line alongside Trossard — leaving him a bit isolated, and giving Harrison some plays off. I’m not sure I saw a single White overlap in the first half.

While leaving Saka solo over there can still pay dividends — he’s Bukayo Fucking Saka, after all — it’s a tall ask for virtually anybody else on earth, which even includes Trossard. He did his best, but he had limited options.

Combine that with some hasty clearances, impatient passes, and a few nice sequences by Leeds attackers (namely Summerville), and the result was a first half which could have easily been 1-0 either way.

To conclude, what became clear from the first half is that if:

Jesus is largely floating left

Ødegaard is also moving left to shed his marker (without rotation to cover his place)

…and Saka is not playing

You can’t reasonably expect huge attacking contributions from the right.

The solution

After a quick, opportunistic goal that saw Arsenal go up 2-0, there appeared to be a conscious effort to get the right-side going, which ultimately resulted in the next two goals.

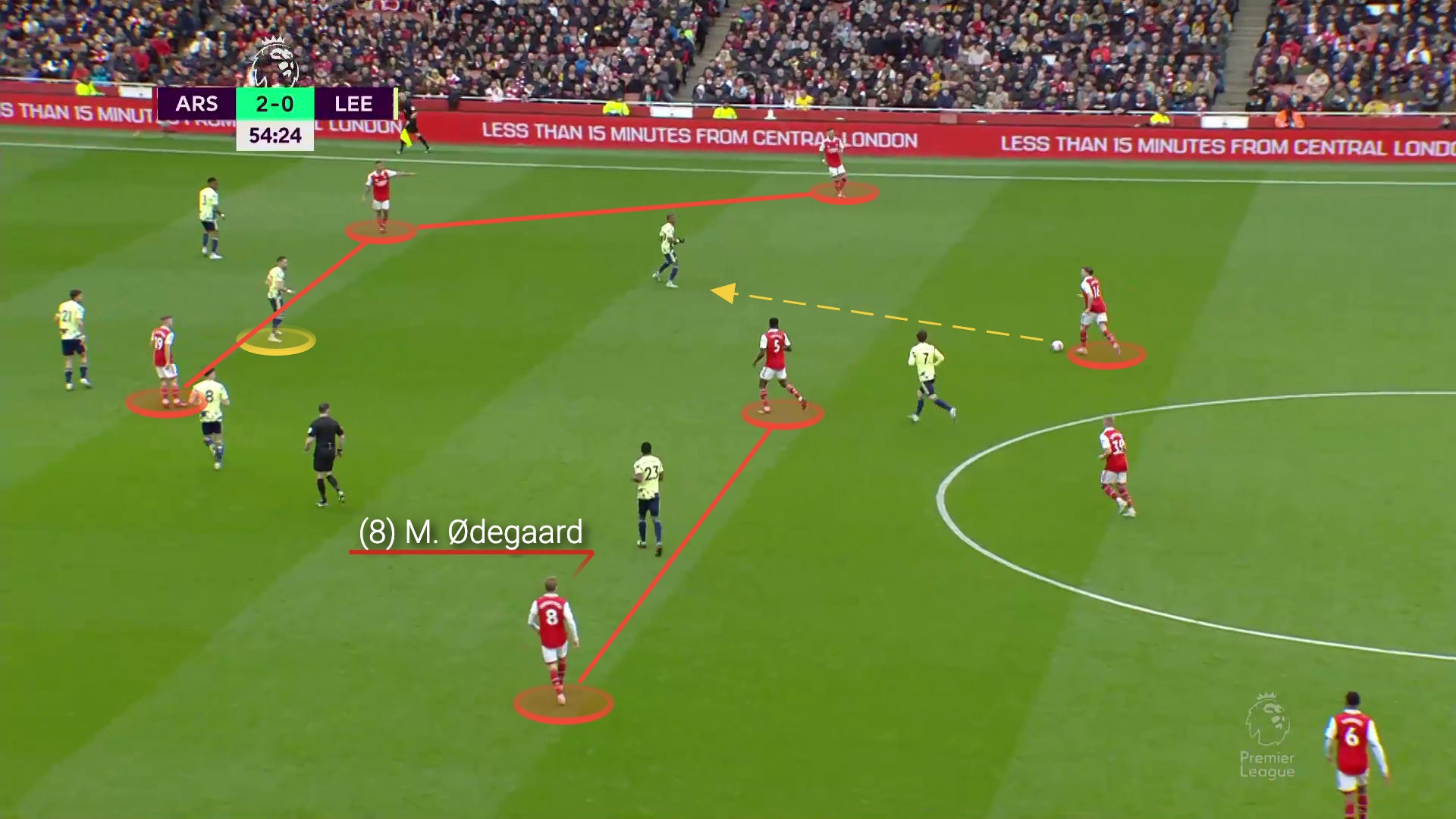

In the next sequence, Zinchenko dribbles up and passes it along to Ødegaard. Virtually everyone is in their normal place, with some minor tweaks: Gabriel is pushed up, Xhaka is dropping deep to make up for how central Zinchenko is, and most pivotally, Jesus is shading right. This is largely what Leeds trained for:

So it’s time to throw them off balance. Ødegaard again dribbles away to pull Harrison out and create space behind. He then starts one of those beautiful Arsenal rondo drills, giving it to White. Ødegaard cuts back up, Jesus cuts across to the touchline, Trossard cuts into the half-space, crisp passes are made, and so on:

With Ødegaard getting it back, the motion continues. White overlaps Jesus on the touchline, but Ødegaard ultimately doesn’t see a direct opportunity forming, and realizes he can pull Harrison back out again, so he dribbles away:

…now that he’s given the ball up to Holding, Ødegaard sprints across the pitch to Zinchenko’s normal spot, which will leave Harrison without his standard assignment:

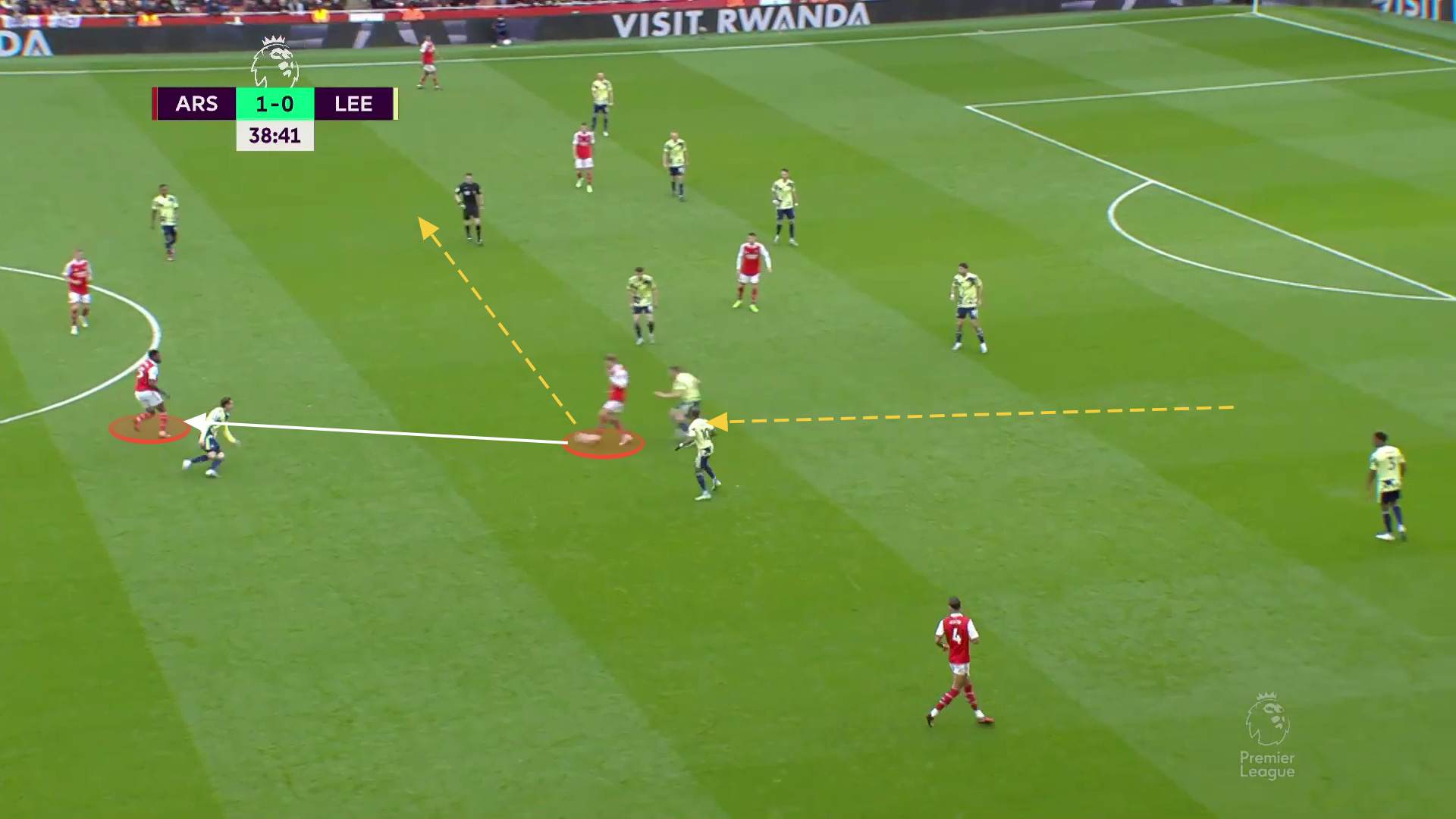

…but unlike most of the first half, there are now players backfilling Ødegaard’s rotations near the half-space. Harrison heads back to his spot, and is now “zonal,” caught in-between marking Trossard and Jesus. With Ødegaard across the pitch, Harrison’s responsibilities are less clear:

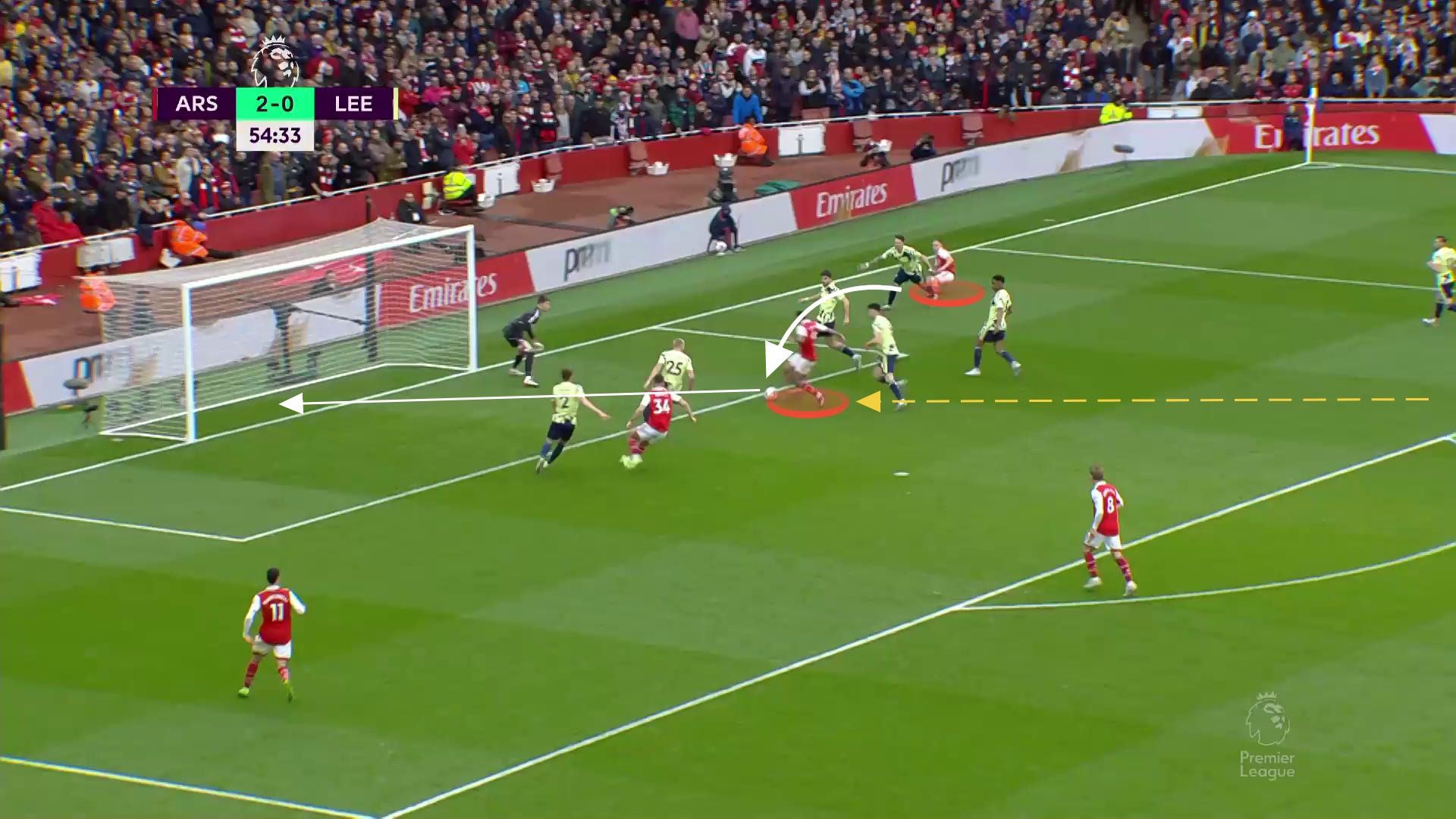

Meanwhile, we’ve covered the importance of centre-back dribbles to get numbers in these situations. Holding does the right thing by dribbling upfield and forcing a commitment from Summerville before passing. This takes him out of the play:

Harrison hesitates. He goes outside, and then back in, but generally gives Jesus the space he wouldn’t afford Ødegaard earlier. This gives Jesus the room for a cutting pass to Trossard:

…and Trossard will need an extra pair of celebration goggles for the eyes in the back of his head. He has a ridiculous control and goes for the cutback cross, somehow laying it out perfectly. Because Jesus is not anybody’s clear mark from the half-space, Harrison hands him off to Roca. Thanks to that moment of hesitation (and, in truth, his pace and effort), Jesus beats Roca to the ball. It’s 3-0, and #9 has a brace:

As much as this was just a display of individual quality, it was also something else: a display of what happens when multiple pivotal chess pieces control the exact half-space that the opponent is trying to take away.

It wasn’t long before Jesus got his rest, and Saka came on at right-wing.

Before the game ended, Leeds was trying our aforementioned Option #1 — ferrying help over to Saka to cut off his ability to attack 1v1 and/or pass it to Ødegaard. His sheer gravitational pull scoops up four defenders, and leaves only one CB in the box (with Ayling and Rasmus keeping an eye otherwise).

But Leeds aren’t quite as good or disciplined at this kind of thing as Newcastle (or Everton was at home). Saka still wriggles free, gets the ball to Ødegaard, who ships a pitch-perfect cross into an unpopulated box for Xhaka to head in:

In the second half, Ødegaard stayed on the right more, looking to add control to the area rather than evading pressure. With some additional rotations and support coming his way, he was able to be more impactful: attempting 11 more passes in 9 fewer minutes, while winning more duels and total actions. In turn, Trossard (who swung inside to striker to close out the game) also started imposing himself.

While play still flowed through the left, the right was no longer being neglected, and the proof was in the 4-goal pudding.

(Why do I type sentences like that?)

🔥 TL;DR

So what did we learn here?

When firing on all cylinders, this Arsenal team can combine what you see from the most disciplined positional teams with what you may see from a Real Madrid in a Champions League game. On one hand, the motive behind positional set-ups is to enable players to play with more flexibility and creativity, because they always have a sense of where their teammates will be. You’ll hear guidelines that make that possible (“no more than 3 players in a horizontal zone,” “no more than 2 players in a vertical zone”), but I see Arsenal breaking those rules pretty regularly. That’s when they play like Madrid. At times, as you saw against Liverpool, it can feel like Ancelotti’s advanced tactics are to put three or four of the best players in the world around a half-space, and ask them to do whatever they think will score a goal; they can feel under-coached in the best possible way. There’s a reason this has been so effective, so filled with moments of brilliance, but prone to occasional inconsistency in league. If you’re able to combine the relentless buzzsaw tactics of good positional play, with a little more combo-laden simple entrepreneurialism of tip-top players when things need a jolt, you have a mighty concoction. Jesus and Trossard naturally provide that. Increasingly, others are joining the party.

In any case, success generally flows from control of the half-space. When Ødegaard is man-marked and dragging his defender around, others have to continue to be intentional about filling his vacated spaces to keep up control of the pivotal zone. Leaving it empty can play into the hands of the opponent.

It’s difficult to overstate the impact of Saka. In a typical game, there is endless support offered to the left side by the floating striker and Zinchenko, but the attack is still balanced because … Saka can single-handedly (footedly?) make it so. Seeing how marooned a wonderful player like Trossard can look in his boots just illustrates the burden he regularly bears.

In Saka’s absence, the team (and the striker in particular) has to be intentional about fostering rotations on both sides. Luckily, Jesus is the best Mr. Fix-It in the business.

In this particular game, my hunch is that Arsenal could have used more of those big rotational diamonds on the right side in the first half. Ayling isn’t at a Premier League level athletically, and had a rough performance whenever attacked 1v1 — but he’s OK at handoffs and communication, so it’s fine to just attack him directly (as the team still did) while trying to generate miscommunications or late handoffs on the Struijk/Harrison/Firpo side.

I will say that back in October, Kristensen had one of the better 1-v-1 performances against Martinelli all year, so it was a little quizzical to throw him inside and start Ayling at full-back. I’m guessing that Gracia liked the physical matchup of Kristensen on Xhaka, but asking Ayling to watch Martinelli and Jesus out wide is a little unkind. It’s no wonder Arsenal was so focused on the left.

In all, Arsenal won 4-1 against a team that gave them issues the last go-round and this time implemented a thoughtful, likely correct gameplan.

Moving forward, as teams seek to disrupt the heartbeat of the Arsenal attack, the second half showed a good blueprint as to how to respond.

Wow, that’s a lot to write about a single fucking goal, he says to himself.

Happy grilling.

🔥

A lot to write about one goal indeed, but also very interesting to read. Thanks for another banger of an analysis!

love this analysis.. subscribed..

now i will go and read your other newsletters.