Bangers only

An investigation into Arsenal’s shot selection and quality, how it stacks up to the primary trophy rivals, and what can be done to improve in the years ahead

It was the spring of 2019.

In a true underdog story, Manchester City hadn’t lost in months, but still needed every single point available to secure another title. Stop me if anything sounds familiar.

Their opponent on the day, Leicester, were plucky and resilient, and the match was a scoreless deadlock into the 70th minute. That’s when Bayern’s new manager took some probing touches into the space ahead.

After a moment of consideration, Vincent Kompany thundered it into the top corner.

The blast secured victory and ultimately left the 97-point Liverpool as the most successful second-place team in league history.

Rewatching the strike, you’ll see Kompany deliberate on an earlier hit before settling himself. His doubt was understandable, especially for a team (and a game) that has increasingly prized higher-quality chances.

In the post-game celebrations, cameras picked up Sergio Agüero recounting his thoughts.

“Vinny, I tell you, don't shoot. Noooo!”

Pep concurred with Agüero at the time. Here was Raheem Sterling’s contribution.

This 31-yarder was, after all, his only goal of the season, and his first goal from outside of the box in 12 years. The xG gods gave him a 3% chance to score from there.

Kompany was defiant.

“I’ve had 15 years of top-level midfielders telling me not to shoot … But I’ve not come this far in my career to be told when I can and can’t shoot.”

Liverpool, heartbroken on that day, have been on the other side of the equation, thanks to a likelier source in a likelier time.

Steven Gerrard, of course, hit this late winner in 2004 to send Liverpool into the Champions League knockout stages.

The goal is commemorated as a plinth outside Anfield.

As we discuss decisive bangers, your thoughts may naturally wander to the famous Zidane volley in the 2002 Champions League final.

The wondergoal earned Zizou his only Champions League victory as a player after losing two previous finals with Juventus.

“My team performed like champions today," said Leverkusen coach Klaus Toppmoller. "But we were defeated by one of the most magical goals in the history of football.”

Some others probably come to mind.

Moments of brilliance, all. Legendary players, all.

These snapshots live long in the memories of supporters. But our memories play tricks on us. Because of all manner of biases, our brains tend to weigh things in disproportionate, and often inaccurate, increments.

Part of the allure of statistical models like xG is that they can serve as a counterweight to our fallible emotions, and point us toward what matters, really, when creating an attacking force deserving of the world’s biggest trophies.

When rifling through the data, one can be led to a straightforward conclusion: the focus should be on generating the highest-quality chances.

No, no, Vinny! Don’t shoot!

Simple.

Or is it?

🎯 Shot distance, quality, and xG

The footballing world writ large, and the Premier League specifically, has been on a steady march away from the days of Gerrard. Short shots rule the day.

The reasons are easy to grasp. For all the punchy memories of these long-range bangers, the numbers tell us that shorter shots are, simply, better.

Says Mark Carey of The Athletic:

If analytics has had any influence in the modern game, we should see an evolution in the locations of shots taken towards higher quality areas closer to the goal. This may not please the fan in the stadium yelling “shooooottt!!” when their midfielder picks up a loose ball on the edge of the area, but it would keep Pep Guardiola et al happy to know that players are making better decisions around the penalty area.

[…]

It looks as though the influence of analytics and time spent on the training pitch is sanding off the edges in reducing those low-value shots. Looking at the percentage of open-play shots taken from outside of the box over time, we can see that there is a noticeable decline. Where previously there were as many as 47 per cent of shots taken outside the penalty area, this was a lot lower last season (38 per cent).

The results of this shift may be more extreme than any analytics acolyte may even expect.

Shot quality isn’t everything — it may be the only thing. Look at this.

As they write over at Soccerment:

This result is quite remarkable, implying that more than half of the variation in team performance can be explained with their shot quality relative to their opponents’.

I repeat: more than half of the variation in team performance can be explained by a team’s shot quality relative to their opponents.

There is good news. This season, Arsenal were a huge outlier in opponent shot quality, not to mention volume.

(Please go follow @datanalyticEPL, won’t you? I’ve leaned on his work lately, and I can’t recommend it enough)

That solves one side of the equation.

Arsenal were elite at preventing high-quality shots.

But what about the other side?

⚔️ Comparing Arsenal with … them

Arsenal know what it’s like to experience the heartbreak of a screamer.

With the season going down to the final day, we were hopeful if realistic. Within two minutes, it was more realism than hope. Our kind were checking our phones in dismay to learn that Phil Foden had slotted this home.

Later in the match, with the outside possibility of a West Ham goal looming, Rodri ended things once and for all.

Both of these goals were from outside the box, but they were perhaps less Kompany than Gerrard (though let’s not overstate things). They can’t be considered fluky one-offs: Foden and Rodri have combined for 27 league goals this season, with 10 of those coming from outside the box.

In a season where Arsenal drew level or past Manchester City on a lot of underlying metrics, this is one of the areas in which our rivals retained their advantage.

But that’s just one kernel to a larger question.

In open play:

Man City had 69 (ugh, nice) goals on 60.54 xG and 519 shots

Arsenal had 56 goals on 54.7 xG and 495 shots

That’s a +13 goal advantage in a tight title race. How much of this is due to superior ball-striking — and how much should be chalked up to variance or results-based analysis? Let’s investigate a little further.

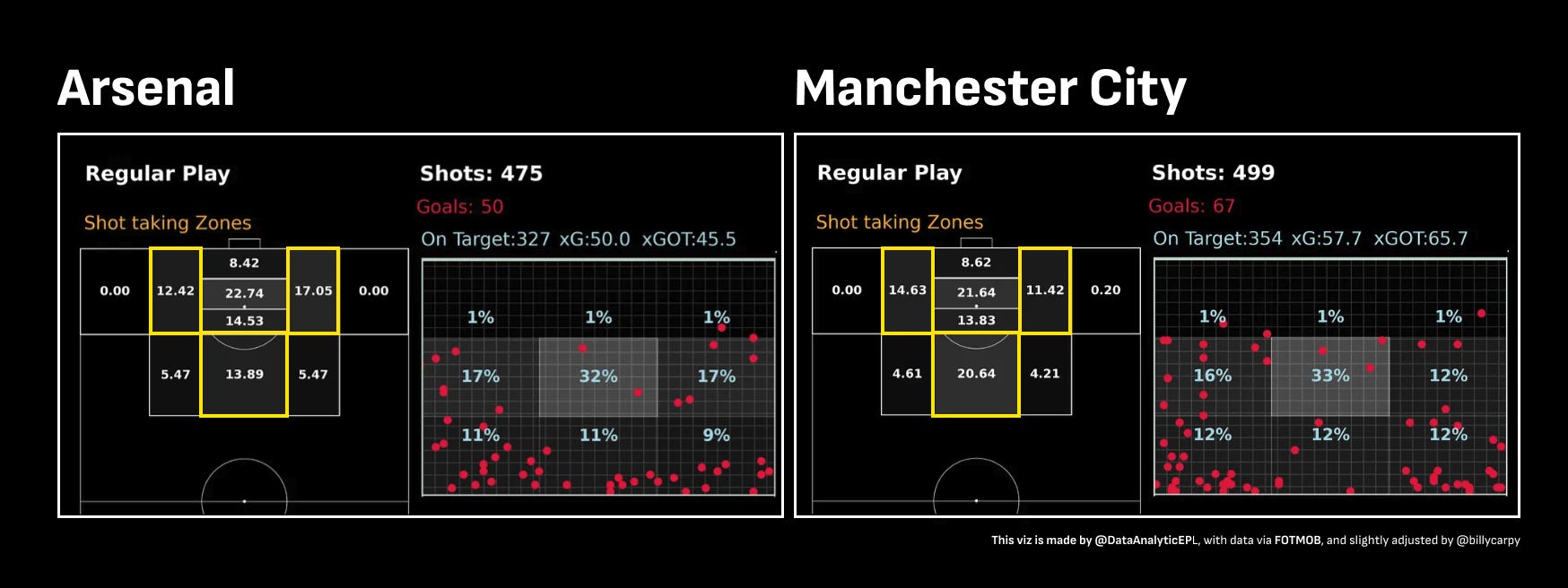

Here’s an overview of Arsenal’s shooting from this year.

…and here’s that of Manchester City.

There are all kinds of little observations you can make from those two tables, but I’ll let you have that fun.

If you take a pure number of Goals-xG, which incorporates every kind of goal (including penalties), the teams were top-two.

Total goals above (or below) expected:

Manchester City: +13.5 G-xG

Arsenal: +9.9 G-xG

This is to be expected. Opta’s xG model, for example, is powered by nearly one million shots using historic data in 40 competitions. This context is so important. If the surrounding characteristics are the same, it will assign the same xG to a shot by Kevin de Bruyne and James Tarkowski. The teams with the best hitters should naturally “overperform” — 0.1 xG shots are not created equally. It is not worth the same to Manchester City and Everton.

…and that brings us back to our questions around shot locations and selection. The first thing to consider is: where do goals come from?

In a general sense, it's fairly clear. A full 40.69% of Premier League goals come from “the second six-yard box,” which I’ve outlined here.

But a lot of set play goals are scored in that area, too. When you only take open play chances into consideration, here’s how the numbers turn out.

With that in mind, let’s compare the shot locations of the two teams.

(Before we go on: I have no choice to mix models a bit here, so please take that as a caveat.)

At the top of this next image you’ll see the first warning shot.

Through FotMob’s model, Man City are up on xG in “regular play” by +7.7 (57.7 to 50.0), which excludes “fast breaks,” set plays, and penalties. That can be overcome by those other means. But Man City are up +17 on actual goals, with a +20.2 on post-shot expected goals. Sheesh. We’ll get into what that means later.

I highlighted the biggest differences in yellow. While you’d love all your chances to be in that “second-six yard box,” it’s not realistic in practice — the opponent tends to make that hard.

As we’d expect, Arsenal’s shot locations tilt right. They shoot 5.63% more from the right side of the box. Man City are more balanced, while taking 6.75% more shots from the top of the box — the area where both Foden and Rodri scored in the final game.

The other difference is how many are blasted into the very bottom of the net in the corners. If you look at the actual placement of the red dots, you’ll see how many more shots are hit on the ground.

OK, so Man City have a slightly more balanced shot selection, shoot more from the top of the box, and aim lower and in the corners.

Let’s look at the longer shots. Thanks to Statsbomb (and @GiantGooner), we have this view of shots from a radius of 18+ yards out from the goal.

You’ll see some gaps in distribution on the Arsenal side, particularly that left corner.

The rest will also tell you a whole lot.

Shot from 18+ yards: Man City took 67 more (or 1.76 more a game)

Statsbomb xG: Man City’s was 16.5, compared to 12.69 for Arsenal

Total goals from 18+ yards: Man City 26, Arsenal 10 (!!!)

In a title race decided by the finest margins, being up 16 goals more from this area may have proven decisive. Just anecdotally, there were certainly several games in which Man City didn’t have the most quality attacking dynamics; then, they hit a banger, and everything was forgotten.

The next thing we can look at is the average open play goal scored by each side.

What you’ll see is that Arsenal’s goals require shorter (i.e. “better”) shots but our rivals are better at adding value to those shots when they boot it.

This showed up in our opposition report, in stark terms. They were polar opposites.

For Arsenal:

Shots on target % had a +0.46 correlation to underlying performance

Length of shot had a -0.43 correlation to underlying performance

For Man City:

Shots on target % had a -0.36 correlation to underlying performance

Length of shot had a +0.27 correlation to underlying performance

That seems to indicate that one team, ahem, had to walk it in — while the other actually fared better when they sprayed it around. This adds some nuance to the “shorter shots are always better” conversation. League averages may only matter so much — the highest echelon of teams are not defended like the others.

📷 Zooming out

Let’s widen the view.

It seems pretty clear that there is room for improvement here to reach the highest heights.

Arsenal have the second-shortest shot in the sample, but are last in terms of “shots on target percentage.” Now, “shots on target” isn’t really the best metric — if somebody pea-rolls a ball to the keeper’s feet it is “on target” but if a truly threatening shot narrowly misses, or is blocked, it is “off target.” But I think that combination of stats sure looks like it could improve.

While the non-penalty xG per shot is on the lower end of the sample (0.11), the gap is small, and it’s roughly the same as Real Madrid, Manchester City, Liverpool, etc. That means that the general situation (space, closest defender, placement of keeper, etc) is roughly in line with rivals, though it could improve.

Then there’s the gap: the post-shot xG/90 and open play goals are all near the bottom of the sample.

Arsenal lead the sample in corner goals, of course.

It feels instructive that Europe’s top-two overperformers in terms of non-penalty xG, Real Madrid (+17.8) and Atalanta (+13.1), took home the two biggest tournaments.

🛑 Block party

But I don’t have too many memories of Arsenal players air-mailing shots.

So where do these “off-target” shots go?

Here’s a primary culprit.

Arsenal had the second-highest % of shots blocked, at 34%. They also had the most long shots blocked in the league (with 69, ugh, nice again). Over 50% of their long shots were stuffed.

In addition to the crowded spaces, I tend to think there are a fair amount of prep touches and slower backlifts on the team. Shots can feel demonstrative and expected.

As the team amasses talent, you want more “where the hell did that come from?” goals. Trossard seems most likely to provide them as it stands. You can see how congested the space is here — if he does anything but fire this off in the first millisecond, there is roughly a zero percent chance at goal.

While we talk ball-striking, many may pine for an improvement on free-kicks. Arsenal, after all, haven’t netted one since Ødegaard got one against Burnley in September of 2021.

In reality, it’s a rounding error these days, as Adrian Clarke covers in this great piece.

Between 2007 and 2014, an average of 32 direct free-kicks were scored per season, but in 2023/24 only 11 direct free-kicks found the back of a Premier League net.

Up until the final round of matches that figure stood at only nine, before Idrissa Gueye and Alfie Doughty struck on the final day. Nevertheless, the total of 11 is a record low for goals scored from such situations.

Yes, that’s 11, by every team, all season. Shots are at an all-time low, too.

Hey, maybe the “lay on the ground behind the wall” thing is working.

Anyway. What does this all mean?

🔥 Conclusions: obvious and less-so

It should be restated that all these stats can be noisy and bouncy. Teams fluctuate in the short-term, and definitely fluctuate on a year-to-year basis, though top clubs usually settle into 10-15% of “overperformance” on xG.

The bounciness is especially prevalent on an individual level.

We have our own example of Martinelli. Elsewhere, Erling Haaland underperformed his xG this year, despite doing the opposite every year of his life. Son Heung-min underperformed last year, and in a haunting moment, underperformed it in a crucial moment against Manchester City this year. Oh, why did I bring that up?

That variance should be expected and baked in. The best you can do is to focus on creating great chances, while also creating a deep bench of potential overperformers — all while looking at things with a lot of nuance based on the players at your disposal.

Here are some possible conclusions to take from here.

In a general sense, Arsenal’s attack is now strong and their quality of chance is fairly high. I am comparing them to the best clubs in the world for a reason, so that must be taken into account.

Arsenal wound up with a solid finishing year. Our non-penalty xG (+7.5) was good for second in the Premier League and 17th in Europe after running cold through December.

Arsenal were tremendous at finding other avenues to score, specifically on set plays and winning penalties. These methods of scoring are not less legitimate, whatever Ange may tell you. If you pin the opponent over and over, they will sit back (which means that finding space is harder) but you are more likely to win corners and penalties.

There is clear room for improvement, in my eyes.

Chance creation (and thus, shot location) can be more diverse and central. We’d certainly like to be higher than sixth in “open play xG created” next year. By rebuilding the left and improving the access on the top of the box, Arsenal will also be able to shoot more from the place on the edge where Foden and Rodri scored on the final day. By preserving as much angle to the goalmouth as possible, you increase your chance of scoring.

Arsenal should continue to tilt their chances toward their best shooters. This sounds obvious, but for much of the year, it didn’t necessarily happen. For large stretches, Martinelli didn’t have enough access to the goal and was underperforming his normal shooting metrics; once Trossard started playing more, he got that access, and started banging them in.

As such, I think there are a few places for Arsenal to more steadily outperform xG in-house. This includes: Martinelli and Trossard crashing the middle; Ødegaard in the “Ø-zone,” where he should return if Arsenal field a double-pivot more often; Rice bangers from the middle-top of the box; Havertz headers; better shooters playing regularly; and Saka anywhere. Oh, and Nwaneri/Vieira 😜

On shot placement, there seems to be some evidence that Arsenal should hit lower, quicker, grounded strikes to the corner. I’d also argue for a slightly greener green light at the top of the box.

Let us not overcomplicate things. This is mostly about players. Sign another great ball-striker or two and prosper. In terms of overall team depth, I think Arsenal are still a touch behind the Champions League’s best on this.

The numbers tell us to mind our shot quality. They also tell us to generate as many high-percentage chances as possible.

As always with football, though, the numbers require a lot of nuance and context — and that’s why I generally believe in being data-informed instead of data-driven.

While I wrap these posts up, I tend to Google around and do some fact-checking on my bullshit; in doing so this time, I noticed that the great David Sumpter wrote The geometry of shooting, a lovely piece on the subject that I can’t recommend enough.

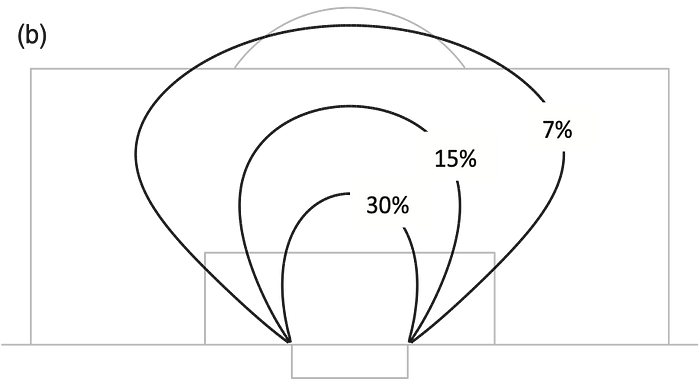

In that article, David separates the conversation from “in the box” and “out of the box” shooting — and funnels it into this simpler graphic.

As David writes:

One important discussion I have had with several players is about the 7% ring. One interpretation might be that a player should not shoot unless they are within this ring. This is wrong! Instead, the 7% ring tells us about how much a few steps closer to goal can increase the chance of scoring. For example, shots from the top corner of the penalty box are 2% chances. A few steps centrally can triple the chance of scoring.

A team should generate the best chances possible. But to be able to do that, you need space; and to generate space, you need to offer a complex threat. One tangible way that Arsenal can improve is by creating more chances centrally, especially on the edge of the box.

At the highest-of-high levels of the sport, the objective is to use the numbers to your advantage — but it is also to acquire and unleash some talent that defies the algorithm, and can blast one in when the math isn’t mathing. How lovely that would have been against, say, West Ham.

You want your opponent to abandon hope. You don’t want to give them a sense of “if we stop their perfectly-orchestrated goals, we’re good.” You want to give them a sense of “even if we stop their perfectly-orchestrated goals, we’re probably still fucked.”

Arsenal’s next steps are interesting and complicated. This, I feel, is an important one.

Or perhaps the answer has been waiting in the wings this whole time.

Be good. ❤️

There's an analogy in poker. You have to bet on some of your weaker hands to increase the power of your stronger hands.

Looking forward to how this analysis factors into your thoughts on a potential striker transfer this summer!