Chelsea and beyond

What the 2-2 draw taught us about what's wrong, what's right, and where to go from here — on identity, defending, issues with creation, second-half changes, and the promise of going long to Kai

Let’s say you’re a pilot setting off on a long, non-stop trip from London to Los Angeles. For whatever reason, you make a mistake at the outset, and start your voyage a single, solitary degree off-course.

This will have big impacts, known as the “1 in 60 rule” in the world of navigation: For every sixty miles you travel, you’ll be another mile in the wrong direction. In this case, unless you course-correct, you’ll wind up some ~90 miles away from Los Angeles.

You probably see where I’m going here. Arsenal started more than one degree off-course on Saturday against Chelsea, a situation a little too familiar with this group. As they kept travelling, the need for an aggressive correction only heightened. Try as they did, they still missed their desired destination, and three points were not available at baggage claim.

OK, Billy, kindly fuck off with your analogies. Let’s see what we learned from the game.

👉 First impressions

The tenor was established early.

Regular readers of this newsletter know that I like to stress how structurally difficult it is to be an inverted full-back in this system, and how, at various times throughout the pre-season, every full-back bar Jurriën David Norman Timber (🙏) contributed to the defensive blooper reel.

Since coming back into the side, Oleksandr Zinchenko has taken his responsibilities seriously. Nearly every metric supports this: he’s losing fewer duels than he ever has, he’s tackling dribblers more, he’s tackling at a higher percentage rate, and so forth.

In the waning minutes of his shift against Man City, Pep sent Jeremy Doku after him — and Zinchenko took his lunch money. Doku actually switched to left-wing shortly thereafter to try his luck against White instead, even before Tomiyasu was subbed on.

There are more than a few examples of this in the season thus far.

But I can’t muster much of my nuance for this one. He got rekked 1v1 against Sterling. Pochettino’s tactics meant that Gabriel and Saliba would be pushed up by rotating false-9’s (mostly Palmer), and Sterling would be free to operate in space against Zinchenko, where the latter’s lack of recovery speed can be exploited.

He made two mistakes in the first minute. At first he defended this well, crowding space, getting his hands involved, leaning forward. But then his steps got wide and big, and that’s not a recipe for success against a Sterling. To compound things, he then was “over-composed,” as he can be when passing, misfiring and creating a shot for Chelsea:

Other facets of the game introduced themselves quite early, as well. Within two minutes, Raya pounded a goal-kick long to Jesus. Colwill won the duel, and it bounced back to Jorginho. Arsenal did eventually control the bouncing ball, but it still felt pretty loose.

Now, Jesus is admirably max-effort on these aerial duels, comfortably outperforming his height. And while I like the circumference of players round Jesus —Saka behind for a flick-header, Rice/Ødegaard/White around to pick up second balls — I find myself wondering if the Jesus vs. Colwill aerial match-up was the best qualitative advantage that the match had to offer. The fact that Jorginho ultimately had to fight for this ball is telling, as well. If you’re going long and looking to make hay with the bouncing balls on offer through the midfield, is Jorginho the right choice? I’m not sure.

And that, really, was my issue with the early gameplan on Saturday. The Man City tactics binder had a clear through-line: a rugged, double-pivot “high block,” that was thoroughly conservative in the first half and kept Jorginho out of having to cover big spaces. With Martinelli coming on at half, it transformed into high-pressing, high-intensity long-ball strategy as the game wore on. Against Chelsea, however, it was a touch more convoluted, with less of a clear identity in the first half: kind of going long, kind of playing out of the back, kind of pressing intensely, kind of hanging back … kind of, kind of, kind of. That lack of clarity translated to the performances.

(And I wrote all that before seeing this Arteta quote from the post-match presser!)

“I think where it went wrong was at the start of the game, I think we didn't play with enough purpose with the ball and clarity, we were just moving the ball without really having the intention to threaten them, and that's a really dangerous thing to do against teams like Chelsea.”

Which brings us to a few seconds later, when Saliba passes to Rice in the middle of the park. You can see the water trail in the thick grass as the ball makes it way. Rice then underhits it to Gabriel — by 10+ yards, turning it into a nice lead pass for Palmer:

👉 The Chelsea strategy

All these contours of the game were introduced within minutes, and Pochettino deserves credit for his gameplan. It followed some of the basic tenets you try to teach in the youth ranks: spread when attacking, squeeze when defending.

It sounds basic, but the best manager in the world got it wrong last time out against Arsenal. Facing a Jorginho/Rice double-pivot, Pep went compact both in and out-of-possession. This helped Jorginho play as a small-space defender, where he doesn’t just clear the bar of “not a liability.” He is a big asset, and that’s why I may lean towards dialing down the press a bit when he plays against tougher opponents.

Pochettino sought to give him a lot of space to cover, both vertical and horizontal. Here, Mudryk got a tad lucky (as he would later), and his diagonal chest pass to Gallagher got through traffic. That said, these slanted out-to-in balls were a potent, intentional weapon in spreading out the Arsenal press, and now it’s off to the races:

This covers another thing they did well, partially out of necessity due to injuries up front. Both Gabriel and Saliba would be high in the list of world defenders you’d relish in assigning a straightforward, all-90 duel: “See this guy? Ruin his day. That’s your job.” You saw it with Saliba against Haaland, and you’ve seen it countless times with Gabriel. Certainly more than he is typically given credit for.

When their assignments are a little less clear, they’re still excellent, but they can feel a little less overpowering. Both Palmer and Gallagher would drop to try and pull them forward, but the twin towers would often leave that bait behind. It led to situations like this, where they’re eyeing who to track — instead of the simpler assignment of “I’ll run with the striker,” for example. Meanwhile, Jorginho is having to cover the wing for White:

…and here was the cross that led to the hand-ball that led to the penalty that led to the goal. You’ll see how fluid it is: Enzo is attacking the wing, Mudryk is running through the middle (followed by a trailing Gallagher), and the nominal 9 (Palmer) is running through the half-space:

All that said, Arsenal recovered pretty nicely here. It was just unfortunate how it turned out. If you’re asking my opinion on the handball call, I may be more sober about it than most in our camp (though nOt LiTeRaLlY).

I think by the letter of the law it’s probably not a penalty. But my personal bar for a big decision like this (penalty or red) is whether you can let it happen several times a game, every game of the year, and things will broadly be OK.

For instance, I think virtually anything shoulder-to-shoulder is fine, and there should be a higher standard for stuff in the far-off corners of the box where a goal is unlikely to occur in the first place, and players are often just lurching for a pen. But I also think you absolutely cannot give a keeper free rein to destroy the attacking line, as Sánchez did to Jesus; that’s a disaster and a major injury waiting to happen. I think Cucurella accumulated about 4 yellow cards, and that’s no bueno, either. But I also feel a little mixed about whether I’d be OK with headers regularly being blocked by the flailing arms of a defender, however natural that may be when jumping. Perhaps it’s just me. Whatever, ignore this.

These wide, stretch-then-pounce interplays were when Chelsea looked at their best — and Jorginho looked at his slowest. He ran a pick on Saka here for good measure:

But I do also want to keep the Chelsea matchup in appropriate context. They’ve spent £1 billion in three windows. This is a perennial-title-or-bust level of spending that has somehow managed Europa-or-bust level expectations. Moreover, while the team composition has been a mess, and I worry that more than a few promising young players will see their paths to minutes become collateral damage in such a profligate plan, I will not hate falsely. The individual talent ID has been stellar from my point of view — they keep picking up guys that ranked highly in all my bullshit stats. Cole Palmer is lurching impatiently towards stardom, used perfectly by Poch. The team’s underlying metrics are all strong.

Still, it’s £1 fucking billion in three fucking windows. This should be a tremendously difficult opponent. The margin of error is stratospheric. They’ve hand-picked top young talents throughout the world, budget be damned. It’s an away game. And yet:

“I really liked going into the dressing room and it’s really quiet, after drawing 2-2 with Chelsea and coming back from 2-0 down,” said Arteta. “Because I know that they wanted more. That’s the positive.”

Let’s look at how Chelsea fared against an increasingly-domineering Arsenal out-of-possession shape.

👉 Chelsea’s attack vs. Arsenal

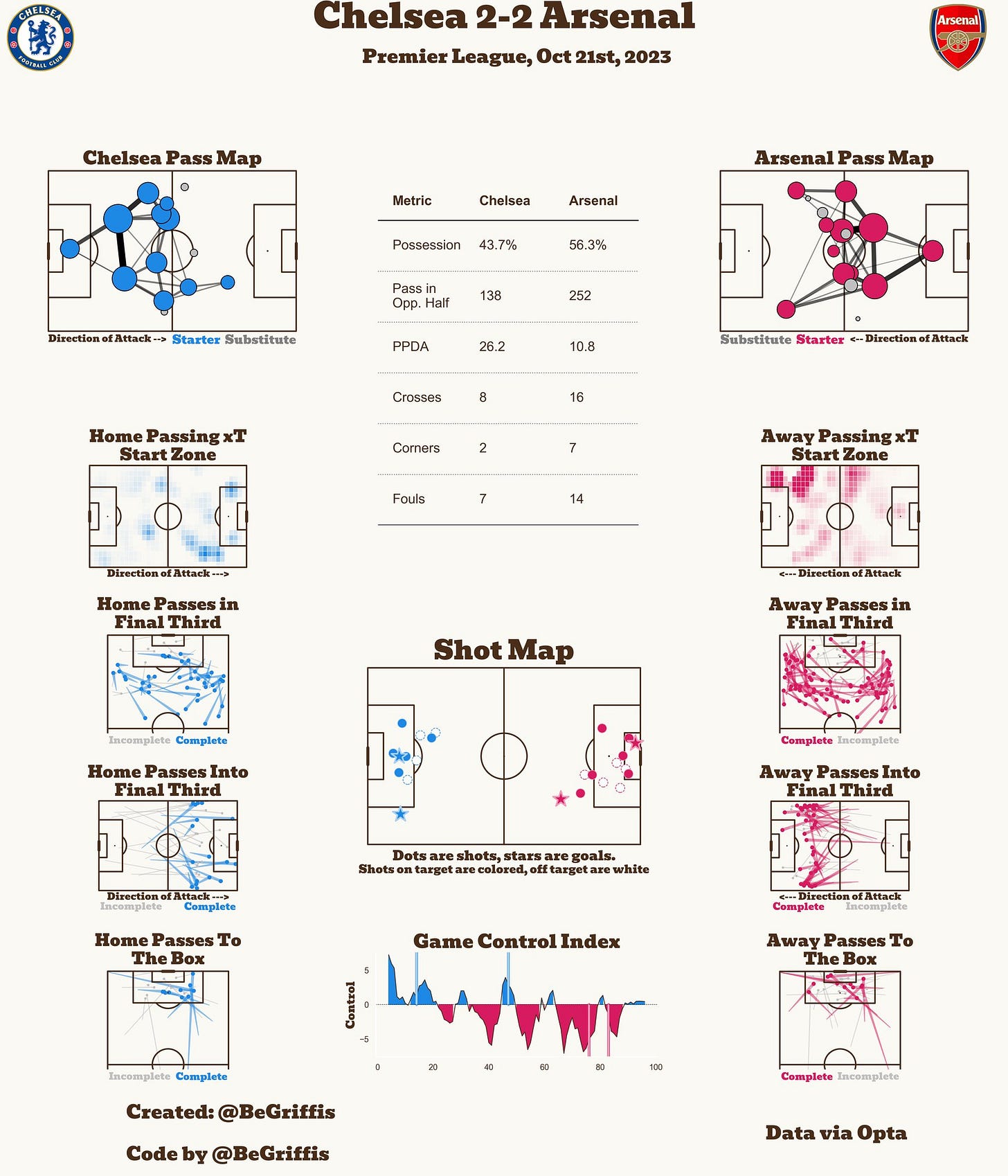

Here are the stats from Opta:

Overall: Lowest xG of season (1.3), lowest possession of season (44%), furthest average shots of season (20.4), second-fewest shot-creating actions (10), most lost aerial duels in a game (15).

Passing: Fewest passes (475), lowest completion percentage (81.3%), lowest distance travelled (6517 yards), lowest progressive distance (2003 yards), fewest passes into the final third (17), fewest progressive passes (20).

Carries/Dribbles: Fewest touches in attacking third (93), fewest touches in middle third (228), fewest attempted take-ons (14), fewest successful take-ons (4), lowest take-on percentage (28.6%), fewest carries by 67. Chelsea had 288 fewer carries than their draw against Liverpool.

Even if Jorginho and Zinchenko had some spiky, memorable moments, this still has all the looks of a world-elite defensive unit.

👉 Arsenal in possession

But what about how Arsenal did with the ball?

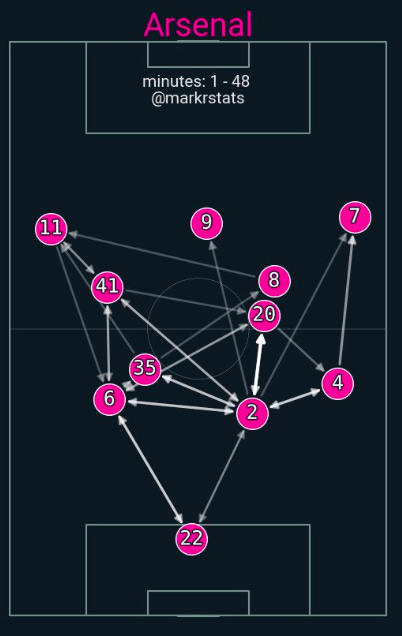

In the interest of intellectual honesty, I must say: as much as I’d like to crow, this is probably the starting XI that I would have chosen, assuming Partey was too big of a risk on the damp pitch. And it’s also true that if I were to create an ideal passmap on the day, it may look something like this:

But it is not necessarily the gameplan I would have chosen, given the corresponding personnel. Hindsight offers us a few lessons.

In deep build-up, you would have seen a purely opportunistic, disciplined quasi-press from Chelsea — not too dissimilar from what we saw against Lens, though in a different shape. Here, you’ll see how actively Raya looks to join the build-up in the LCB role:

I’m a big fan of mid-to-high blocks like the one Chelsea employed. In addition to the Lens comparison, it’s also what Arsenal looked like in the first half against City. The entire point of playing out of the back is to draw pressure forward, and then take players out of the proceedings. These kind of blocks give the defenders the opportunity to keep the opponent honest, without risking getting removed from the equation. It’s the best of both worlds, and inherently frustrating for a team who wants to gain advantage through build-up. The relatively passive nature of the press also makes some of Arsenal’s foibles less excusable; it shouldn’t have been particularly difficult to move the ball around. The conditions probably played a factor.

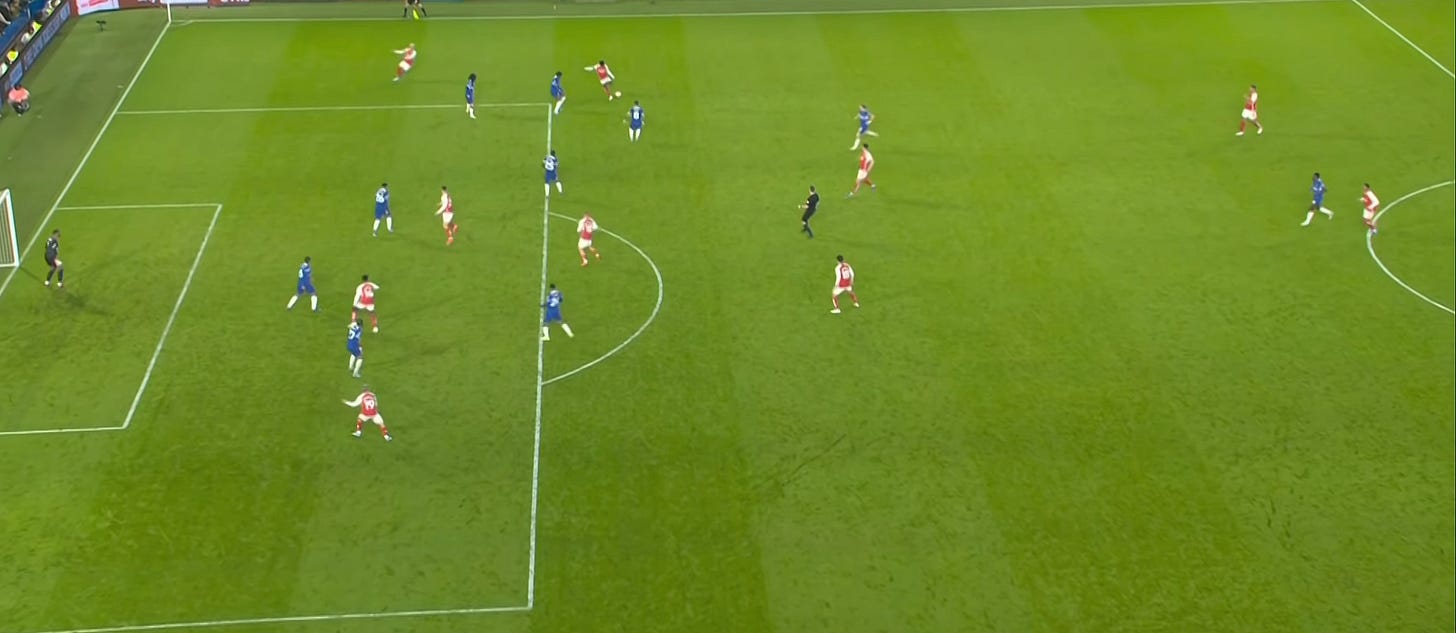

As Arsenal moved forward, you can see just how compact things are in a 4-4-2 block. This should be one of the lasting images from this one, and I’ll explain why:

Colwill was following Ødegaard from behind. Caicedo was leaning a bit towards him. Enzo was essentially shadow-marking him. Gallagher was too. Even Mudryk shaded that way. This is the equivalent of those games when Saka is triple-marked. It’s just a little less easy to spot, visually, so Ødegaard tends to get less credit.

Teams are increasingly learning that if you can cut off access to Ødegaard, you can kill the link between the progressors and the last line of attackers, because there is not enough creative outlet otherwise.

This was a particularly extreme example of defending him. In any game, Ødegaard is constantly moving, gesticulating, looking to open up lanes for others, so in these situations, I’d typically just counsel that those around him need to drop into the gaps he leaves (something, say, Nketiah hasn’t taken enough advantage of yet). But honestly, those gaps didn’t really exist on Saturday. There were simply too many players clogging the middle, and Ødegaard doesn’t have enough bursting running power to offset something like that. Chelsea were fully committed.

Moreover, it warrants further investigation, but there does seem to be a kernel of truth to the idea that he is missing the connection with Partey. While the Rice/Ødegaard relationship hasn’t been bereft of interaction — they traded 22 passes against Lens, for example — that number was only 2 on Saturday, and 2 in that half against Tottenham (although there are reasons for both). Rice passed it to Ødegaard a grand total of zero times in this one.

When he did get the ball, he couldn’t get on the same page with those in front of him. Here, for instance, I thought it was fully rational to play Jesus into the space. Jesus held up his run and hoped for the ball to his feet, a characteristic that probably describes too many of our players. The end result is that it looked like a bad pass by the skipper:

The result of all this? Arsenal increasingly vacated the middle completely, as we’ve seen multiple times this year. Look at how wide open the middle of the chess board is here:

This may seem like a white flag, or a failure, but really, it was fully practical. After Arsenal attacked the wide areas, the very play that you saw above wound up as one of the better chances of the first half.

Jorginho had a few moments of aforementioned struggle when he was stretched as a defender, but looking at his pass map for a 70-minute performance, it sure looks like a great balance of safety, clarity, directness, and work through the middle:

So what happened? I’m sorry that it’s not more interesting, but it’s this: the wingers lost their battles.

👉 Struggles on the wing

Out left, Gusto largely was able to keep Martinelli in check. His agility allowed him to keep up, and his small steps, leans, level of focus, and discipline with lunges allowed him to keep pace with the threat. These are the kinds of straight-up, 1v1 fights that are so rare for Arsenal wingers … and they didn’t take full opportunity, especially early.

On the other side, Cucurella struggled last year in the huge-space, communicative, team stuff, and certainly wasn’t helped by a thoroughly dysfunctional system — often the terrible version of a “passive press,” the worst of both worlds. But he can be a capital-D defender in the right situation, and it’s one of the reasons I had him on my list of options (as a loan) after the Timber injury, despite your boos. In a strict 1v1 he can be awfully balanced, feisty, annoying, and technically sound — crowding the winger, leaning forward, taking tiny steps, and using his hands well.

And that was the case, for sure. But what was also the case was that he was hacking the shit out of Saka with impunity.

On that one, because the VAR check was just triggered, Arsenal received nothing. No card, no foul, no free-kick, not even a throw-in.

Here’s one that’s less dangerous and perhaps even more obvious.

There were several others. On the day, Cucurella only received two fouls. Saka received three. I don’t know what we’re doing here.

There were still moments of relative brilliance. Jorginho had some great cutting passes. Zinchenko hit a beautiful through-ball to Rice, and his outside-boot shot sailed narrowly wide. Saliba looked as Saliba as ever.

It may have felt familiar to some of the chance-creation struggles thus far in the campaign, but I’d argue that this was slightly different, as would be expected from a different lineup. Whereas the team usually hasn’t struggled to progress the ball (first in touches in the attacking third), or even get it into the attacking penalty box (third in the league, higher than City, among others), it’s the final action that has been lacking (ninth in shots, 13th in expected assists).

Here, the progressive stats were on par with the usual rate, but they lost their duels out wide. This led to only 4 touches in the penalty box in the first half, down from a usual rate of 12. Zero shots on target in the first half.

Not nearly good enough.

👉 The second half

I’ll have to be quicker from here, as the Sevilla game is coming up soon, and I’d like to get this up beforehand. So let’s roll.

Tomiyasu started the second half, and things felt a little better, until they didn’t. Are you wondering if I thought the Mudryk shot was intentional? I’m old fashioned. If a guy who is known to be inconsistent with technique never looks at the goal, and uses his off-foot to swing in a looping ball to a central runner, then laughs maniacally with his teammates when it miraculously goes in … I’m going to guess no.

From that point forward, Arsenal’s mandate was crystal clear, and they benefited from that sense of purpose. They initiated way more duels, won way more, recovered the ball more, and passed with more directness:

In terms of game flow, you’ve probably seen stuff like “field-tilt,” threat, and even simple possession making the rounds. They all have their value, just so long as you use them with appropriate context.

But they can have difficult capturing the reality of a David Moyes style game, whereby a team willingly concedes possession but functionally dominates play anyway. I say this because Chelsea fared better than their field-tilt would suggest. Ben Griffis has a good stat called “Game Control” that feels closer to the truth, because it “includes on-ball and off-ball pressure such as passes in the final third, shots, forcing the opponent out of the final third, keeping their possession deep, and interceptions.” See:

Declan Rice was incredible in this one, and, as is becoming a theme, looks at very best when the game is in flux against a tough opponent. There are more results-oriented examples, but his stubborn effort late against Lens was perhaps most encouraging.

You know what happened next. Rice single-footedly brought the team back into the game, launching the furthest-range goal for Arsenal since 2006-07.

When I watch that, I feel the need to do the airplane noises one does when feeding a child.

The behind-the-net view may have been just as impressive. It is a ridiculous thing to bend it into here from 36 yards out.

Here was my wife’s reaction: “I didn’t know people could do that.”

A couple subs loomed large, and with a well-stocked bench (that Vieira didn’t even make!), Arteta is quickly disabusing anyone of the notion that he’s not a good tinkerer. He just didn’t have the materials before.

Tomiyasu is looking really good in that left-back role. He is not offering the line-breaking forward passing that one might hope for, but his burst is more than back, and he led the team in second-half ball recoveries (with 10). Him shutting down that leaky wing is a big reason the second half felt better, and as the team got more athletic, the “rest defending” — i.e., the shape you hold if/when you lose the ball —got increasingly suffocating for Chelsea. That Rice goal didn’t actually come out of nowhere; the press was improving.

👉 Kai’s big head

…and then, of course, there was the double-sub of Havertz and Trossard right after the Rice Rip. With ESR already on for Ødegaard, Kai started out on the left in his more expected role, helping keep the ball pinned and doing well.

And at 84’, that’s when Poch made a double-switch of his own, taking off two of the primary tormentors of the day:

This led to a corresponding change from Arteta: ESR would move left, and Havertz would switch into a “free 10” role behind the striker (Nketiah). We can call this whatever we want, but I call it: “fuck it, we’re going long.”

…and just as it did against Man City in the Community Shield, or against Crystal Palace with 10 men, or against Brentford in the Carabao, or against Man City at the Emirates, it paid immediate and clear dividends. We should be close to done debating his impact to date. I’m not sure we could have expected more of a decisive points contribution than we’ve received already, and I don’t think anyone would argue it’s a solved problem yet.

Readers. This was the first fucking play of him doing this role on Saturday.

We praised Jesus earlier for how max-effort he is on these aerial duels. On the contrary, look how easy it is for Havertz.

You know what happened next. At Jurassic Park, Dr. Ian Malcolm warned us that life finds a way. At Stamford Bridge, Cucurella could have heeded a similar warning about his opponent: whatever your perfectly-laid plans, Bukayo Saka always finds a way.

Saka, donning the captain’s armband, provided the decisive assist.

To me, this all feels like more than a nice moment in a game — it feels like a flashing red sign about what should come.

Let’s oversimplify: generally speaking, with some exceptions like Bournemouth, teams are no longer actively pressing Arsenal. They’re staying in compact, mid-ish blocks. This makes it difficult for Arsenal to capture the advantages of playing out of the back: without pressers, there are few guys to pass through and take out of the play. On top of that, Arsenal have lacked the ability (and desire) to generate the requisite chaos in the opponent box; it is crowded and relatively static back there.

BUT! Arsenal now have perhaps the best long-balling keeper in the world. They now have one of the best aerial targets in the world. In Rice, Saliba, Ødegaard, Havertz, they have some of the best loose ball recoverers in the world, and an elite rest defence that can keep it forward, and some good chaos-merchant passers. These moments create the potential for disorder in the opposition that is all too rare otherwise.

TL;DR: Let’s kick it to Kai’s head a whole lot more and see what happens. This can be at striker, sure. But Saturday showed what I’ve been yelling all year: if he starts at “left-8,” there is no reason Havertz can’t just rotate up to be the aerial target with Jesus falling in behind. This turns him into the unicorn he potentially is.

He already did this with Nketiah at Brentford to good effect. See:

…and see:

In terms of positioning, something interesting about Havertz is that he excels at link-up play while leaning a little right, but seems to be a clearly-better finisher in his home left pocket.

In his career, he’s played a lot more on the right, and has rarely scored from over there. Here are his career goals — you’ll see a little gap on the right:

Which brings me to my final point on this one: I see little reason that Ødegaard and Saka shouldn’t just be spamming 4-5 far-post crosses to Havertz a game. We’ve barely seen it at all, and to my simple mind, it looks like money laying on the ground.

👉 Finally, on Raya

I’ll wrap up on Raya. Here was his passmap:

You’ll always notice a degree of caution in my #analysis of keeper positioning. Here’s why. If you don't have a goalkeeping background and ever go down a rabbit hole of training videos, reading, and/or listening to what actual GK's have to say — you'll quickly understand how much of what you know about “good positioning” may not be the case. Take it from me! A lot of goalkeeping is overriding some base impulses on what feels obvious to do, and a lot of the wider discussion around positioning is, well, horse shit — or, perhaps, Win shit (that’s our dog).

But I will say this. Raya’s little pass to Rice was a brutal read, and almost a costly one. I cautioned about things like these inevitably happening from the opening scouting report on, but when it actually happens, it certainly doesn’t feel great. Let’s hope that it’s part of the normal settling in process.

But I find something to be missing in the discussion about Raya, and that is how much more is asked of him. We saw him rushing up to play LCB yet again. This has the practical effect of making him much more influential in build-up and general play. This comes through in volume, with Raya making about 18 more passes per game on average. Over, say, a 38-game slate, that means he would pass about 680 more times than Ramsdale. Can we understand why there may be a couple more nervy moments in there? Even with lower volume, Ramsdale’s had moments of his own. Can we say with any certainty that, given 680 more passes to attempt, Ramsdale wouldn’t be contributing a lot more of those? I sure can’t.

👉 Finally

In all, we are a short period from Sevilla kicking off, and I’m probably picking the worst time to post this. Meanwhile, the Arsenal we know are changing:

It is clear that the defensive structure of the team is improving. I’m not in a rush to attribute this all to the safety of the passing. There’s Declan Rice, a still-improving William Saliba, and some tactical tweaks that put the players in better positions to succeed. There is certainly the potential to do all that while tweaking the risk/reward quotient in the final moments.

Here’s to hoping that happens — starting today.

Personal note: last week, I had the pleasure of writing a huge read for SCOUTED on why we get young players wrong — which looks at Henry’s time at Juventus, among other things. From there, found some old hand-written scouting reports of great players, and dove into some of the psychology of why we miss, misuse, or misunderstand players as they come up, and how to do better. There’s a trial thing if you’re not a subscriber. Enjoy!