Cue the music

Some observations after the Everton win and before the Champions League anthem, including: how opponents are changing, why the attack feels different, how to better support Saka, and much more

Our reputations precede us. For some, especially so.

I remember listening to an interview with a celebrity — I forget which one — describing some of the unexpected trade-offs with fame. One of the sacrifices was that they had all but lost the ability to make a first impression. From a certain day forward, almost everybody they’d meet would have a predetermined expectation of them.

It’s been almost four years since Mikel Arteta was introduced as head coach at Arsenal. Though he would establish a reputation in the transition years, his full vision would come into focus during last year’s campaign, setting the league alight with a vibrant style of play, resulting in a surprising, nearly season-long perch atop the table (and the highlight reels to match), and a long-awaited Champions League berth. The chosen scheme was linked with its ancestors but contained many aggressive changes, including inverted full-backs, higher lines, “fake 10’s,” more active rotations, and much more.

In the world of music, follow-up albums are notoriously difficult. In the world of film, save for a few notable exceptions, sequels are notoriously shit. Expectations are mounted on a high bar. The audience wants something exactly the same and brand new, all at once. Good luck.

Football can be cruel in this regard. Smart, experienced thinkers, buttressed by mountains of data, spools of virtual tape, and some of the best athletes in the world, are paid millions to ensure your sequel flops. For every action, an equal and opposite reaction.

However much has been written about the changes to the dynamics in this Arsenal side through five games — Kai Havertz! Declan Rice! David Raya! Jurriën Timber! 🙁— the most underreported change is the one that sounds like bad teenage poetry: this year, last year has already happened. Unlike the previous go-round, teams have now watched a full season of Arsenal’s title-challenging ways, and a reputation is fully conjured. There are no more first impressions.

Opponents are adjusting. While Arsenal are more likely to show security and clarity in their approach, their foes are even less likely to commit forward. Their buses are fully parked: opponents are allowing Arsenal to complete 21 passes in our 60% of the pitch before launching an intervention, compared to 14.1 last year. Meanwhile, their challenge intensity is down (6.1 to 5.4), and so is their tempo (16.16 to 14.5).

To varying degrees, these dynamics remain true when adjusted for opponent.

What results is an opposition attack that is less enthusiastic, less committed. This is due to a few reasons. For one, their wingers are pinned back to help with Arsenal’s, so they have trouble getting up the pitch in time to generate sufficient threat. For another, opponent attacks occur less because Arsenal lose the ball fewer times in possession. And finally, Declan Rice.

There was a moment in the second minute that showed some of this — though, in fairness, it wasn’t too dissimilar to what Everton may have tried last year.

Early on, Arsenal were struggling with the speed of their passes on the long Goodison grass. Zinchenko’s dish out to Martinelli was batted down by the pesky green blades, which helped Ashley “Old” Young step in to intercept. On the other side, look at how deep the full-back Mykolenko is, of course — but also the opposite winger, Dwight McNeil:

Doucouré makes an excellent, dangerous run through the middle, but Rice can peel over and safely dispatch the opportunity with relative ease. In previous iterations, Partey was able to do these tasks quite well, but Rice is probably the preeminent player in the world at them, and adds a bit of soul-crushing inevitability to the equation. Attacks are often stopped before they even get started:

Meanwhile, and tellingly: because of how many players Everton still have back, there is no opportunity to counter the counter. Rice just dinks it away and Arsenal start a new possession.

In his post-game comments, Dyche was especially mournful about these missed opportunities:

“Defensively a shift was put in by the players and we were pretty effective on the defensive side of things, but on transition there were so many loose passes and that first pass is so important … Then of course having the energy and the mental energy that when you do work in transition you are then active and it is not just everyone waiting for the chance to break, or the chance to build… In the end I think that link on transition was missing and in the end we were not effective enough.”

Arsenal lead the league in final third possession, with a 72% “field-tilt.” This has led to suffocating defensive numbers, including a total xGA (expected goals against) of 4 through 5 games. Bernd Leno made more saves against Arsenal (8) than Arsenal have had to make all season (6).

That’s all positive, but there have been knock-on effects. One is that there is less opportunity for chaos and pressing. Opponents have 34.6 fewer touches in the middle third per 90; if you watch through goal compilations from last year, you’ll see how many of them started with a feisty repossession in the middle of the pitch, and ended with a goal against a block that was trying to get resettled. Those chances still pop up, but the bouncing ball is more rare; when it does appear, the opposition usually hasn’t flung too many attackers forward anyway, so the opportunities are lacking.

There’s another, chicken-and-egg factor at play. Arsenal are scoring a little less because they’re scoring a little less:

With early strikes, the game opens up, and opponents are forced to move out of their comfortable block to try to, uh, score goals. Without those deficits, their buses are more comfortably parked.

So if this is the new reality, what is the antidote?

🏝 A visit to Saka Island

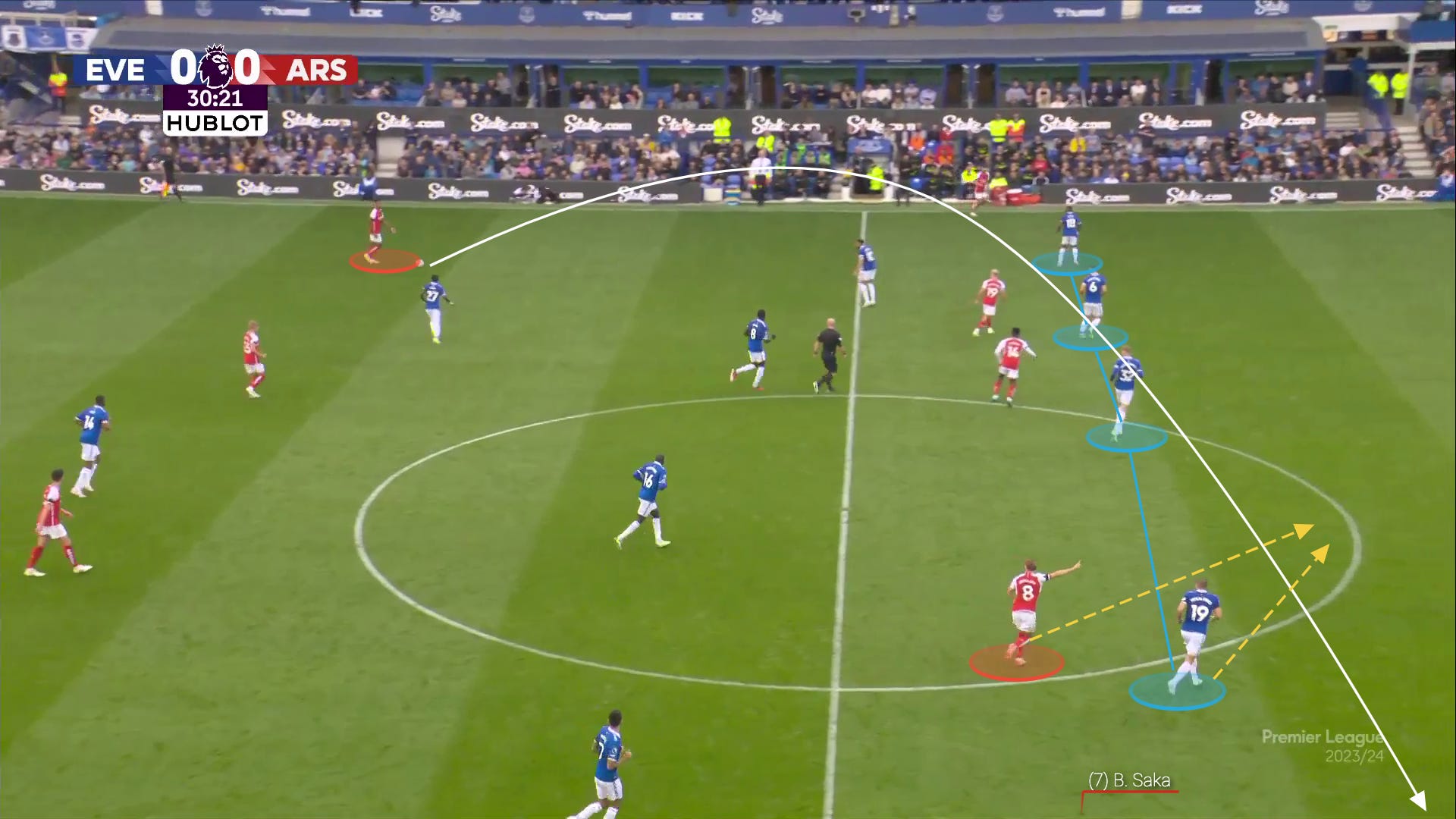

As an Arsenal supporter, one of your biggest questions may be how to avoid situations like this:

It’s a good question. Right at the outset, I have three points to raise:

The first is that if Saka doesn’t manage to heroically score from these situations, he has not necessarily had a bad game. Look at what the guy is dealing with.

The second is dispelling the notion that these situations are even inherently negative. This is a ridiculous amount of attention for one man to receive. Not only does his starpower open up the middle/left of the pitch, it’s also defensive: Saka is pinning McNeil’s ability to offer any attacking threat. If you ever wonder where Saka ranks among the world’s most-feared attackers, just look at how top managers defend him.

The third is Ødegaard. I’m all for tweaks, rotations, and evolutions, but swapping out another player here does not miraculously change the dynamics of a 6v2.

So how do you generate higher-percentage opportunities? You move quicker — either by more decisively ushering reinforcements his way, or by switching the play with more force.

You may wonder why Saka is usually double or triple-teamed, but occasionally finds himself isolated 1v1, and what factors are in play to make it so.

At 15’, he was again walled-off, but still managed to move it forward through a nutmeg — though it was still ultimately a 5v2:

At 18’, he carries it up to a triplicate of double-teams:

(“Triples makes it safe. Triples is best.” - Sean Dyche)

Saka is one of the best progressive carriers in the world, and the value of these carries can’t be overstated; moving the ball up and holding width is the primary function of Pep’s wingers right now. Why? Vertical passing into the final third can be difficult and lower-percentage. You get Saka or Martinelli on the wing, and whatever happens, the defenders turn negative, back-pedaling from the off. Voilà, the ball is progressed.

But to understand how to unstick these situations, we have to look earlier in the play. After moments like these, Ødegaard usually has some observations to act upon.

With the play on the left side, Everton are doing their customary, disciplined job of defending. They are leaning ball-side, tracking underlappers, and crowding both the middle and the overloaded side at the same time. With that lean, Ødegaard is being tracked by Mykolenko while Saka holds width. Everything is as it should be:

But here’s where things change. With Trossard deciding what to do, Ødegaard wants to free up width — so he drags Mykolenko on a striker run. This may be a decoy run, or a genuine threat, but it does the job nonetheless. That run triggers McNeil to drop back and cover Saka, and Trossard fires it across the park to White, who then delivers it out to Saka:

…and look, no more 6v2 or 5v2. Saka is now 1v1 on a winger, with space to operate, and an overlapper around:

This resulted in a White cross, a Rice shot, a Vieira cross, and another near-chance.

Here, Ødegaard is highly demonstrative about another over-the-topper when the ball is on the left, only for Gabriel to hit the player behind him (Saka) with the intent of giving him space. The pass was a little off and McNeil was able to disrupt it, but the idea was repeated:

Ten minutes later, you can see how Ødegaard again picks up Mykolenko and pulls him through the middle, so a switch can get hit out to Saka in space. This resulted in some good interplay and that left-footed shot by White:

…and, of course, in the rare moments when there are numbers out there, shots and goals come. This is why opponents are so fixated on shipping out help:

Arsenal remain tremendously dependent on Saka to move the ball and hoover up attention. He has 59 more touches in the attacking third than any player in the Premier League. The squad can continue to better support the effectiveness of those touches by creating better conditions: not just switching it to him, but pairing off-ball runs with those switches to drag defenders away and give him a fair fight.

When the opponent achieves defensive overloads, as they often did at Goodison Park, I do think Rice and White can rush up to form a diamond with increasing velocity, and not just when an overlap is possible. I have some other thoughts.

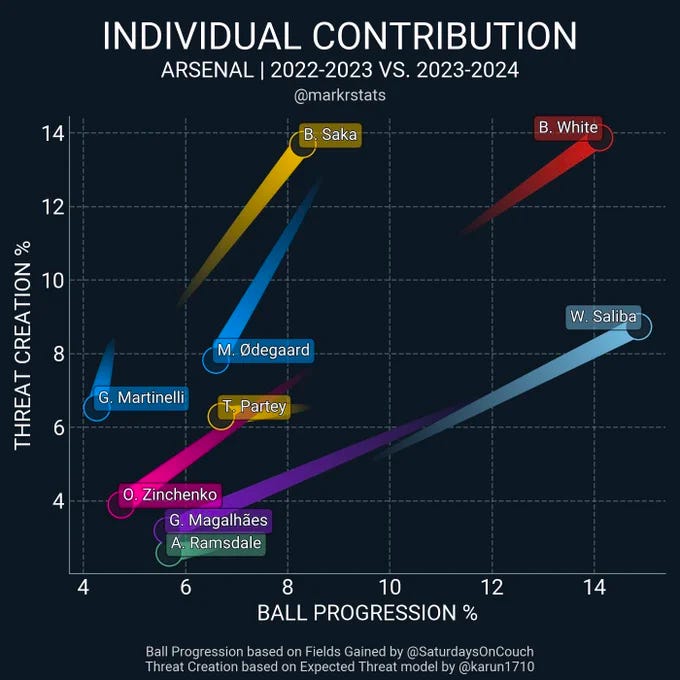

⚪️ Credit to White

Still, that’s splitting hairs. Progression and threat have become increasingly driven by the right:

You’ll notice something else from that graph: while playing two positions, White has been creating as much threat as anybody, and progressing the ball as much as anybody. He’s yet to come off the pitch, for good reason — he’s 25, and still improving.

Wyscout credited him with 80-of-91 passing on the day. His switches, in particular, have looked marvelous thus far, always weighted and driven to perfection:

…and seemingly every time I rewatch a game, I find a few subtle moments of the dark arts:

Ødegaard’s evolution has been interesting. Previously so passive in front of the net, last year, at 22-years-old, he was able to match Kevin De Bruyne’s high for goals in a season with 15. It’s still early, but this year, he’s passing a little less, assisting shots a little less, getting the ball in the penalty area a little less (15 times total, the same amount as Matty Cash), and shooting a bit more.

As always, he is orchestrating the out-of-possession look and triggering a lot of coach-on-the-pitch movement (like the above) through his tireless work. But particularly with the scoring-focused Nketiah and Havertz often in the lineup in the year so far, I’m not sure the off-ball, goal-hound interpretation of his role is what I would have chosen for him.

It’d be nice to see him swing out wide more and let Saka operate in the half-space. Some more far-post crosses and Enzo-like scoop passes would be a sight for sore eyes; I also think he can help drive the ball right-to-left closer to the box, instead of relying on deeper players to do it. He’s capable of all this and more.

When Jesus is in, vacating the central areas, helping along the relational play on the right, greasing the rotations and contributing everywhere, I’m better with his more shot-minded approach.

🪵 Winning ugly (with a pretty lineup)

I wrote a whole thing before this game to place emphasis on the importance of set pieces, and discussed Arsenal’s ability to field its largest lineup in twenty years. Naturally, Arteta responded by starting the shorter keeper (Raya) and the much shorter option at left-attacking midfielder (Fábio Vieira).

The team’s intentions were clear in the first action. It’s become the weekly routine for Ramsdale to knock the opening play up long, provoking his teammates to fight for a second ball up the pitch. Here, with a smaller lineup, there was little advantage to doing so. Raya dished it out short to White:

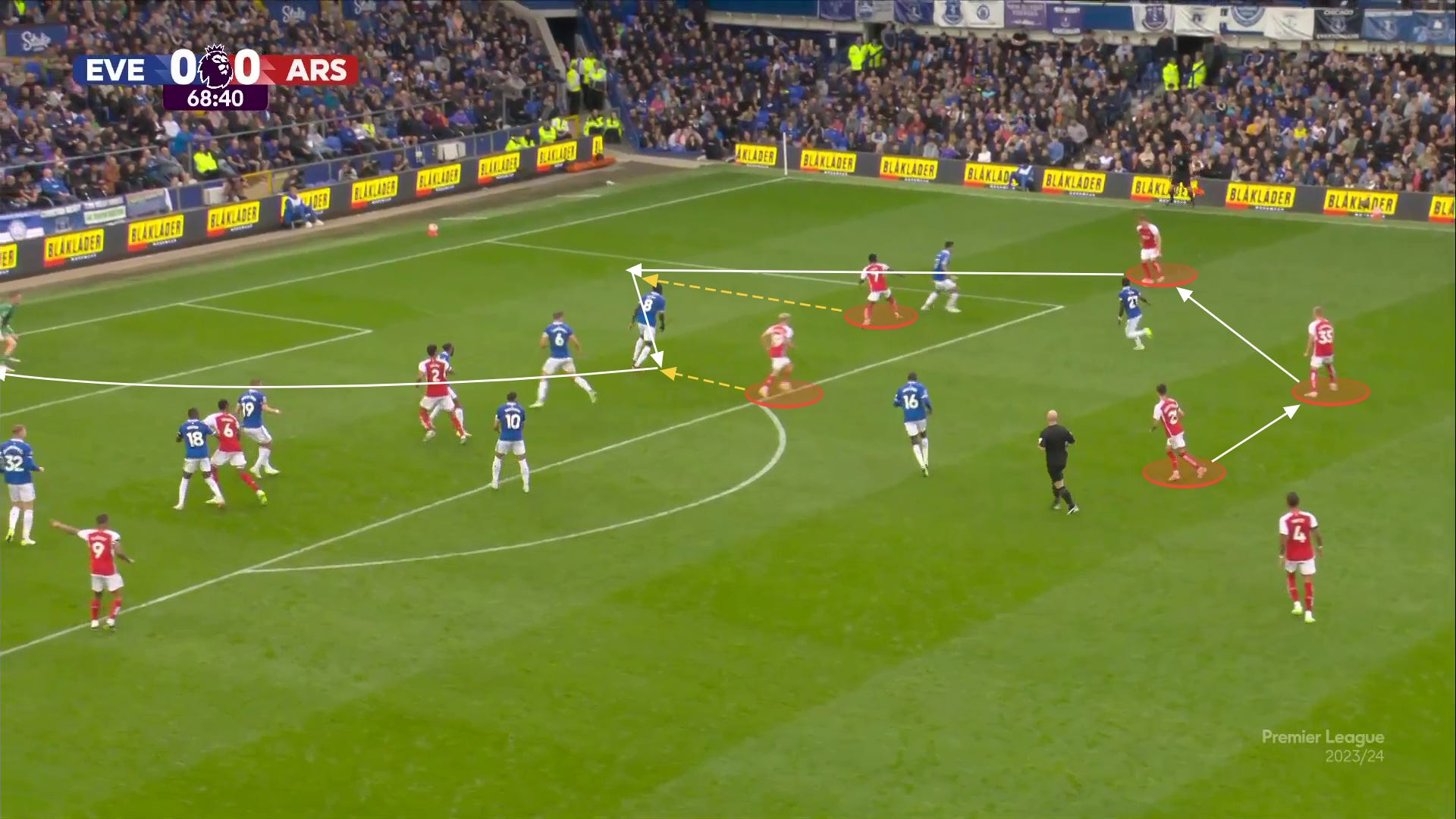

The plan was also showcased through an increased battering via the short corner routine, in which Everton’s advantages in the air were nullified and their bulky lateral agility was exploited.

The crispness and discipline in this set of actions was a sight to see:

In a perfectly fitting moment, the Large Man who floated over this Arsenal team last year to put in the winning goal (#6, James Tarkowski) was sent flailing outside the box to track the small Vieira, before hustling back into the goal mouth to try and block the small Trossard’s chance. His efforts were in vain:

Perhaps most promisingly, Declan Rice, Saliba, Gabriel, and White were able to marshal a defensive look that suffocated any opportunities from Everton, fully compensating for an undersized lineup that featured an advanced midfield of Ødegaard and Trossard.

I beat the drum all last year that aesthetics aside, Vieira was a capable defensive contributor — especially when rest defending, where he runs hard and frequently pokes the ball away.

The best way to nullify the opponent’s threat on corners is by making sure they don’t get them in the first place. Everton only earned one corner all day; Arsenal had 11. Rice is looking every bit the platform signing we hoped him to be.

Raya, for his part, looked perfectly in control. If not for a sense of profound loyalty to Ramsdale, my coverage of the new keeper would admittedly stray towards fan-fiction. So let’s move on before I embarrass myself.

👈 What about the left?

On the left, dynamics are still being discovered. We’ll find that in many cases, these players aren’t plug-and-play, but fairly dependent on the interlocking profiles of the players beside them. Arteta keeps stressing the importance of revealing relationships on the pitch, and this area is probably the clearest example of that.

I think it’s likely that Gabriel Jesus was the domino that led to this lineup. With him working back to fitness, and his Champions League services required later in the week, Nketiah was next up for a start. The Nketiah/Havertz dynamic hasn’t shown much promise, at least not yet, with the two having some redundant positional impulses. Havertz was also signed with one eye towards the Champions League. Combine that with some sparkling recent form from Vieira, and a decision is made.

The shared characteristics of a Martinelli/Vieira/Nketiah trio look good, though we only got a short glance. Vieira is starting to regularly display the output of a €35m player, and if one of his best skills — his shot — didn’t let him down, this was another star turn. Here was his passing map:

I’ve always thought his size can lead to false impressions, as he shares little in common with a Bernardo Silva. He does kick the ball a bit like Bruno, but can have a more low-touch, high-impact mindset of players bigger than him; he is the first new signing to whom I ascribed sneaky-raumdueter qualities. He has fully solidified a regular role, right when he needed to; “like a new signing,” etc.

Once Martinelli went out, I would have leaned towards Reiss Nelson to fill his spot. With Nketiah camping in the middle, a more prototypical wide 1v1 dribbler may have found more joy against Ashley Young. Trossard nonetheless looked more vibrant as the game wore on, and a trio of Trossard/Havertz/Jesus works as well, with all three comfortable in each role.

Especially after the examples provided last year when playing Everton, I’m still not so sure of why Nketiah is quite so central in a game like this. I understand the concept of occupying CB’s, and think that prototypical strikering can still be the base impulse, but openings are only found by forcing the big guys to shuffle back and forth or otherwise confuse their assignments. Nketiah has been incredible this year; I’d still like to see him move around a bit more here. He received six passes on the day.

Overall, it was a good team attacking performance — one which nonetheless left some meat on the bone. Tie in a “BBQ” reference at your leisure.

🔥 Final thoughts

Before too long, the anthem will ring, and a dangerous opponent will loom.

PSV is undefeated in nine matches thus far, scoring 28 goals along the way, led by a deep attacking force including Chucky Lozano, Noa Lang, the electric Johan Bakayoko, and Luuk de Jong’s big head.

The new-look squad is packed with intrigue, ranging from steady Eredivisie hands, to reclamation projects, to top talents like Armel Bella Kotchap. (Not for nothing, as he’s probably a rotational piece, but I really love what I’ve seen of 18-year-old Isaac Babadi, who has so many clever passes and moves in his repertoire). The team has been steadily high-possession and high-press thus far, and may not fall neatly into the category of defensive looks we’ve witnessed to date. A more open game may be on offer.

In short, it’s a test worthy of the Champions League. It will be downright fascinating to see the makeup of Arteta’s side, and the degree to which he leans towards strength and control with his new weapons.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I’m off to go pulsate with anxiety. Or is it excitement?

Happy grilling everybody.

🔥

Think Odegaard read this. He was collecting balls from deep and helping with buildup and those scoop passes were indeed a sight for sore eyes. Or maybe Arteta read this or both did ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

!!!