Everything you need to know about Roméo Lavia

A scouting report on the game of the Arsenal midfield target. Where does he excel? How "raw" is he? What’s his long-term profile? Where would he fit in now?

Much can be said about Pep Guardiola. If his outfit had successfully pulled off a late swoop of Declan Rice, I’d have a few more things to add. For now, I’ll be more obsequious, and say this: Pep Guardiola notices things.

As a small, terrible example, I remember stumbling upon an anecdote from a Bristol City assistant after a Carabao Cup tie. Pep invited their coaching staff to join him for a post-match meeting, showering them with his usual Peppy compliments. Before long, the conversation turned to information-gathering. He wanted to know, among other things, the strategy behind their pitch markings, and what tactical benefits they offer. The guy was like “uh, they play rugby here too.” Ah.

He did some noticing a year later in Belgium, too. Accepting Kevin de Bruyne’s invitation to attend the KDB Cup, an international youth event, he soon locked his eyes on a 15-year-old midfielder who was orchestrating play, keeping the ball, and eventually winning the tournament.

A year later, that player — Roméo Lavia, as you’ve already surmised — signed his first professional contract with Man City.

It’s been a whirlwind since then.

An introduction to Lavia

If we were to look for a similarly pithy way of describing the real subject of this article, it’d be this: Roméo Lavia bets on himself.

Reports have linked the midfielder with Arsenal:

Talks have been held over moving for Lavia. The 19-year-old is likely to leave Southampton after their relegation from the Premier League and is valued at £45m.

Chelsea have registered interest in the Belgian, who has also been watched by Manchester United and Liverpool, but there is growing belief he will end up at Arsenal.

Back where our story began, reports suggested that there were ample voices, even from the City side, that recommended Lavia stay in Belgium at the time. It was certainly understandable considering the difficulties of navigating such a stacked system. But thanks to a “very strong character,” he wanted to make the jump.

After a handful of appearances for the U18’s, he quickly moved up to the U23 level. There, with the EDS team, he won the club’s first Premier League 2 championship and got voted Player of the Season in a side flush with budding stars a year or two (or three, or four) his senior.

It was a fruitful experience over 18 months: studying Fernandinho’s game, mostly playing a Rodri-ish incarnation of the 6, earning a few senior team call-ups as a 17-year-old (including a start in the Carabao), and once making the squad for a Champions League game.

By 2022-23, Fernandinho was set to leave, and reinforcements were necessary for the senior squad. Being the sole cover for a player as important as Rodri was a hell of a task, and Pep ultimately judged it too gnarly of a responsibility to lay upon the talented feet of the 18-year-old. He turned to the more seasoned Kalvin Phillips — signing the Leeds midfielder to a six-year deal and a £42 million transfer fee.

This made Lavia’s path precarious. Armed with that aforementioned “strong character,” and the sneaking suspicion that he was ready for every-week Premier League starts, despite his age, he pushed for a transfer, betting on himself again. Thus began the season that we’ll cover in some depth here.

Anyone who has watched him for a moment will know he’s plenty talented. But how “raw” is he? How ready is he? Where does he still need patience and development? Can he earn enough minutes in a side looking to win trophies?

I’ve watched a fair bit of him this year, but for this, I did late-night speed-runs of ~10 matches, going back to his youth days for Man City. Here’s what I found.

His year for Saints

There are two things that must inform any analysis of Lavia’s game.

First, his team. It was bad, except against us, finishing last and ending an 11-year stay in the top-flight. Tactically, he navigated the demands of three different managers — Ralph Hasenhüttl, Nathan Jones, and Rubén Sellés — all of whom nonetheless gave him every-week starts in the most difficult role in the game: the number 6.

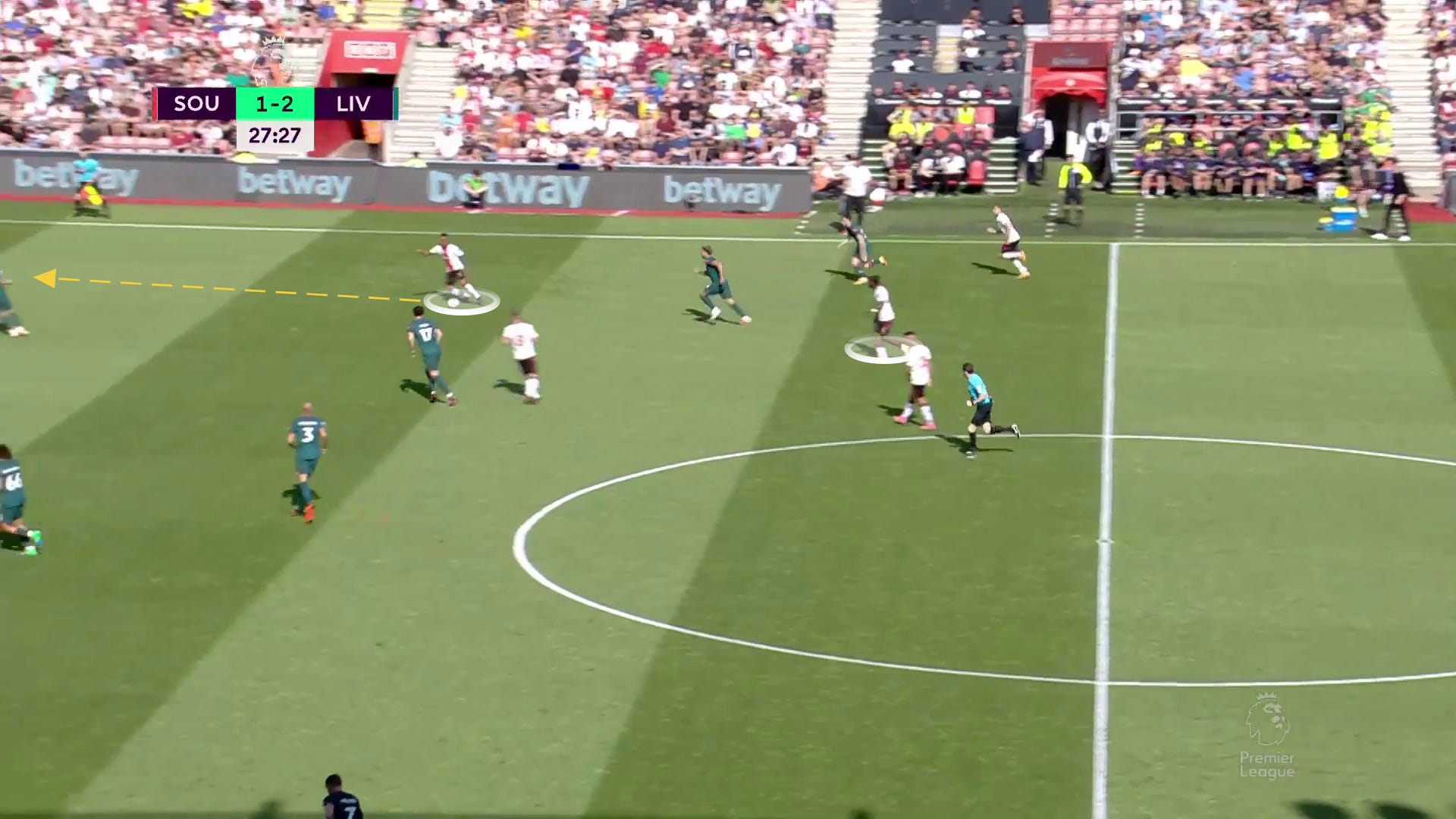

This deployment as the deepest midfielder was true even in the opening weeks, when Oriol Romeu was still on the squad — a player now linked to play the role with Barcelona. His interpretation varied a bit throughout the season, sometimes with James Ward-Prowse in an actual double-pivot, sometimes playing more advanced, but he racked up all of one (1) touch in the opponent box. Often, it was a pretty “true” and lonely version of the lone 6, as you’ll see in a build-up shape here against Wolves:

His midfield partners weren’t the speediest, particularly JWP, which led to niggling spacing issues, and gave Lavia a lot of ground to cover.

The team wasn’t fully practical — which may have been bad for their results, but wasn’t the worst for his development. Rather than sitting back and playing hoofball, they generally played semi-open by the standards of a cellar dweller, going low-possession but not no-possession — running a normal press (11.66 PPDA per Wyscout), and attempting (at least at times) to play out the back, and not opting for fully parked buses through a variety of formations:

Nonetheless, they scored the third-fewest goals, were pressed a ton (the equivalent of playing Arsenal every week), and had the worst goalkeeping performances in the league by some distance. Their post-shot xG allowed was +.57 goals per 90 higher than would be expected (!).

Second, we must again consider his age. Now 19, he’s got a full Premier League season under his belt. At the same age, Thomas Partey was on Atlético Madrid B, a year off from joining Mallorca on loan in the Spanish second level. Moisés Caicedo was playing for Beerschot. Rodri had one start for Villareal.

When Lavia was born, Zlatan was midway through his third season at Ajax.

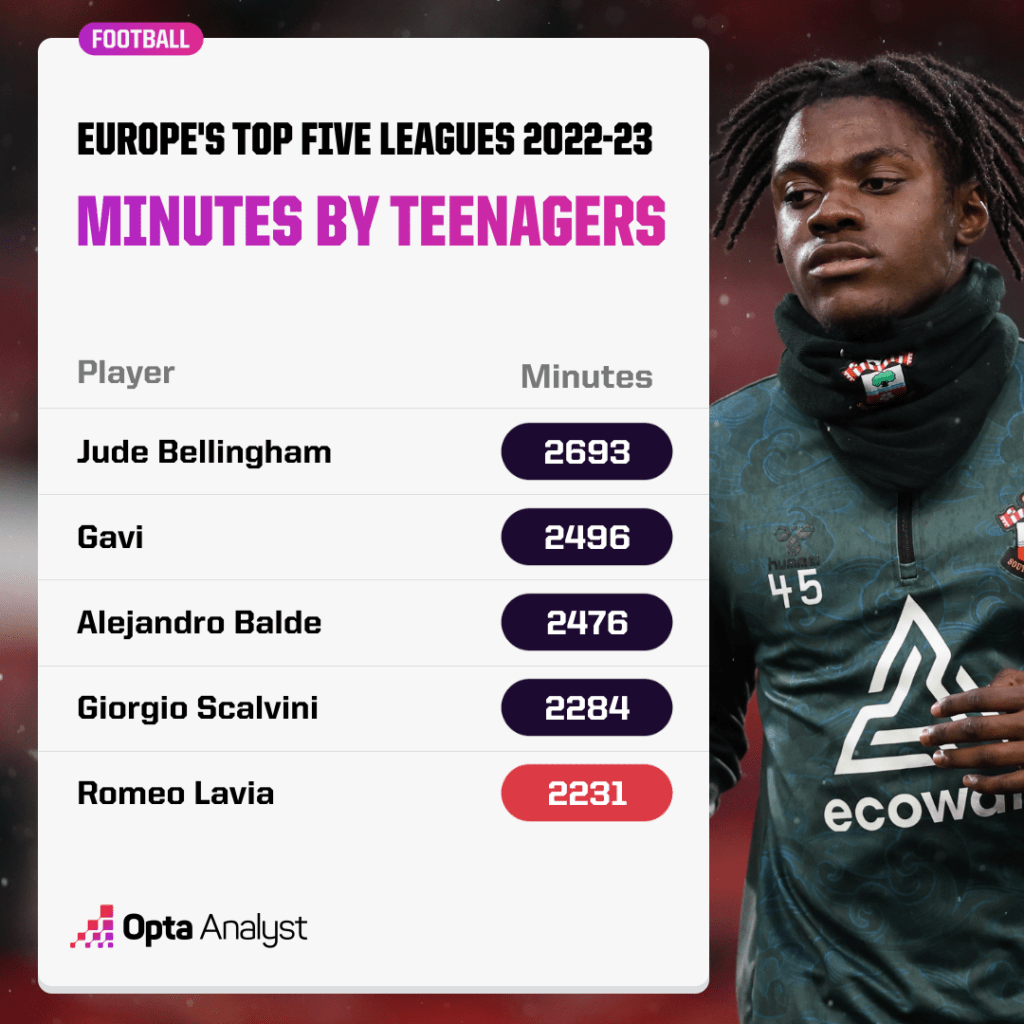

Not only did Lavia lead Premier League teenagers in minutes, he looked plenty promising and fairly comfortable from the jump. If you turned on his first match against Tottenham, you may have thought to yourself — “So I’m supposed to believe Pep is a genius for noticing that this guy is talented? Hell, I can do it, and I’m the guy who dropped my iPhone in a urinal last November.”

In that debut, he had 66 touches, 96% passing, 7/8 (88%) ground duels, 11 passes into the final third, and 13 recoveries. In his fifth start, Lavia became the first player born in 2004 to score in the EPL, netting a beautiful banger against Chelsea. (Before you ask, no, he hasn’t shown much shooting range other than that). He came off with a hamstring injury after helping his team to a record of 2-1-2.

Without him, the team lost the next four games, attempting unsuccessfully to cover his responsibilities at the 6. By the time of his next start, they were 3-3-9. The team continued to struggle from then on, while Lavia kept shining (though unevenly at times).

It’s no wonder he took home the team’s Player of the Year award, winning 41% of the public vote over players like Ward-Prowse.

It’s been skirted around, so I’ll say it more plainly: he did so in the hardest position in the world, for the worst team, as the youngest weekly starter, in the hardest league in the world.

Passing

One doesn’t need a full rubric to judge Lavia’s passing repertoire. A binary system will do: depending on the pass type, he’s either wildly advanced (1) or nowhere (0).

The good news is that the huge majority of the passes he uses are in the former camp; I’d conjecture that this is because, compared to his peers who have ventured around the pitch in their younger years, he’s played a pretty specific role for most of his life. As such, he has mastered many of the “defensive midfieldery” type passes.

Let’s start with the good stuff.

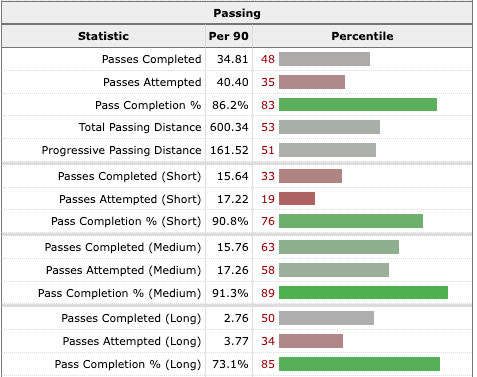

Lavia was pressured more than any Southampton player last year (with 18.8 pressures per 90), and completed the highest percentage of passes on the team (86.2%). When pressured, that accuracy rate only dipped to 79%, which puts him roughly on par with a player like Thiago.

When judging a player on a shitty team, look at the efficiency numbers rather than the volume:

A few of his moves are already fairly elite. The first one is something that should be heartening for Arsenal fans when thinking about the potential void in the defensive midfield. He’s excellent at winning (or recovering) the ball, and immediately pushing it (or recycling it) in one touch after the win. He generally needs no time to adjust or think about what to do with it:

If you’ve read my newsletter over the last year, you’ll know a pet peeve of mine is an uncontrolled recovery or hurried clearance. The art of taking an opportunity like that and actually doing something with it is often what separates the good teams.

This first one is not gonna be that impressive, but I think it’s instructive. Here, he watches as Firmino tries to kick off an attack:

…and waiting for a loose touch, he goes in there for the tackle. Where he’s unique is that he often makes the tackle and the pass in the same motion, because he’s already felt out what’s happening around him:

…and this kicks off an attack the other way:

Similarly, you can see how he leaves his man, pokes it away from Jones with a pass to JWP, gets himself available, lets it run, and then knocks an attack forward with his left:

No wasted touches.

As you saw there, he always uses the most advantageous foot. Next, he’s being closed down on his right side, so he knocks the weighted through-ball with his left:

Right after a duel, he can sometimes fall into the trap of going too hard, too fast upon repossession, but there’s a lot to like there.

In more standard build-up, it’s in the modulation of tempo, control, and press-resistance where he looks most comfortable and beyond his years. The things that you’d hope a young player would pick up over time — metronoming, availability for the ball, communication, 360° feel, anticipation, decisiveness, back-to-goal comfort, little digs and tricks — are already there.

Here against the Newcastle press, he’d been scanning while he awaited a pass. With JWP joining in a pivot — this doesn’t look too different from some Arsenal shapes, by the way — he identifies that the middle of the pitch is going to be crunched with a defensive overload, so his first pass is a press-buster out wide to Lyanco:

His timing with line-breakers is sublime; he’s not just a patient recycler. Here, he sees the Armstrong run unfolding, but knows there’s not an appropriate lane for him to hit it through, so he pushes his touch over to the middle to clear out Longstaff:

…and then hits it through the lane he vacated:

He’s good at those Brighton-y, subtle, studs-on-ball manipulations.

Finally, his ability to play diagonals is where he may be most unique; some real affordances have to be made when profiling him in this regard. One can see a ton of potential in his skill when receiving directly from a CB, shuttling the ball up to the exploitable zone of his choosing, and then rifling it directly to a winger (without any of the foreplay).

Here for the Belgian u19’s, he turns and offers a low, weighted bender to play the wide man into space:

This gif will give you a perfect snapshot into what it was like to play for Southampton much of the year:

Likewise, he’s able to offer similar passes with his left, though with slightly less consistency:

And Arsenal fans will remember the kind of things he was doing against us. Here was an outlet ball to Walcott:

It has not been perfect, though — as I said, it’s all 1’s and 0’s.

His passing errors come in two forms: shanks, and overconfidence against the press. (Plus, bad runs and controls by his teammates, but we won’t cover that).

On the first front, there is usually a pass every game or two where you go: oh yeah, he’s a teenager. The mishit can be so extreme as to be funny. Occasionally, you’ll see something like this on the passmap:

This helps inform the understandable perception that he’s raw.

Here, he tried to modulate one of those diagonals by putting some real power behind it — and just hit it straight to Kulusevski’s feet:

Some of his (rare) crosses barely leave the ground, and just pea-roll into the box, harmlessly.

Needless to say, he’s still ironing out technique on some pass types, but for the major things — press-rondoing, weighted through-balls, diagonals — he is already quite locked-in.

This leads us to his final issue in the passing game. Where you’d usually be preaching calma to a young defensive midfielder, Lavia occasionally takes it to an extreme; not in lack of effort, but in excess confidence. There are a couple howlers this year, like this ball that was intercepted by Jota for a goal in the season finale:

It is, however, important to keep things in proportion here. His first-touch control is perfectly sticky (.97 miscontrols a game); he is a 90.8% passer in the short range, and a 91.3% passer in the medium range. His shanks are usually overly-ambitious hits into advanced areas that don’t turn into the counters the other way. And the shorter, more grounded passes are rarely mishit.

He is more likely to get in trouble with a carry, which we’ll cover next.

Dribbling & Carrying

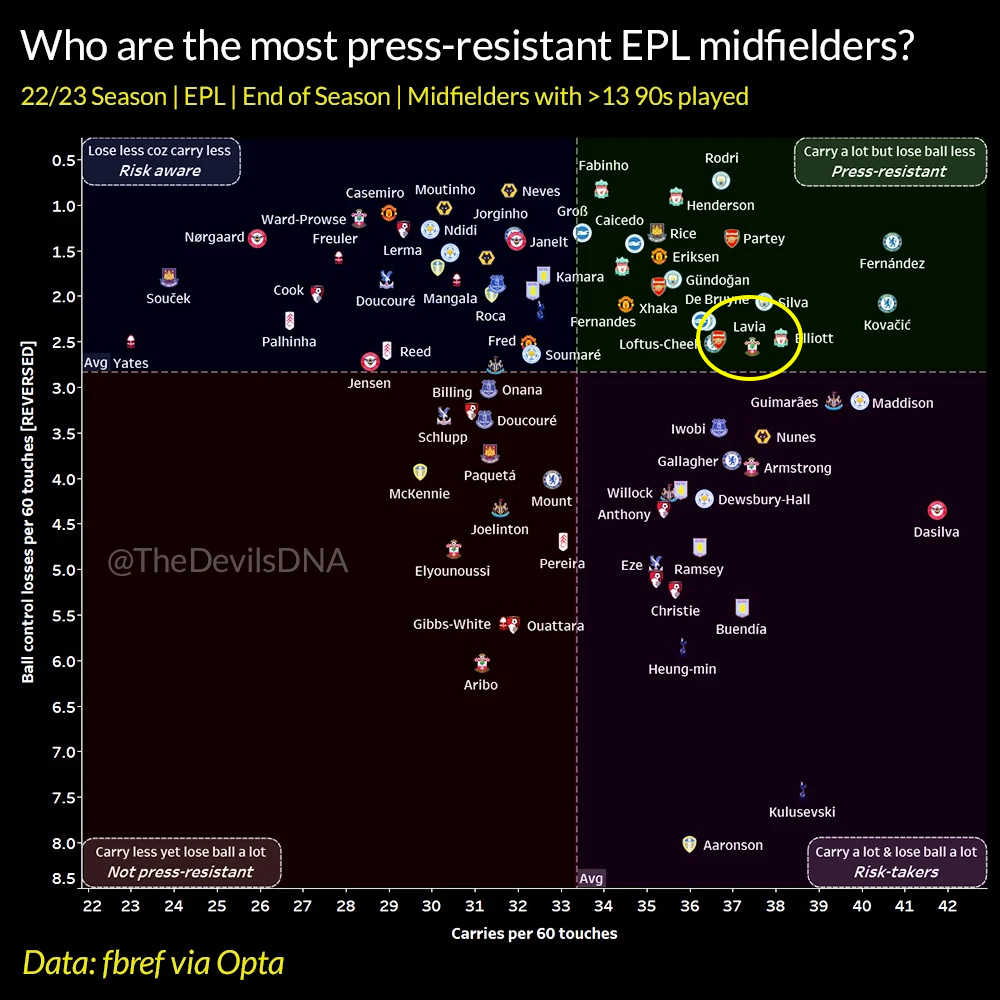

This is a somewhat incomplete, but still useful, view of press-resistance:

Here, you’ll see a fairly ambitious, successful profile:

Unlike a Declan Rice, he is not likely to burst through the midfield on a lone carry to blow past several defenders with speed; he is more likely to carry forward and survey the pitch for the right pass. But he does have ample “phone booth/box agility,” where his comfort with surroundings and tight spaces, coupled with good balance and an understanding of where players will be, helps him navigate difficult situations:

You can see how quickly he moved after the pass there. Ten seconds later in the same game, you see Lavia take Rodri out of the play at the top of the box and set up Sulemana:

He is probably too confident in his turning ability — a lovely weapon that he overuses. This is the kind of play that he gets away with, and will make comp videos, but is perhaps too eventful at the 6 of a top side:

An easy counterpoint would be that this was a necessary evil at Southampton. Look how far the distances between himself and the other midfielders are.

I’d still say he loses the ball a bit too much, and tries to muscle his way out of situations when a more straightforward pass will do, or tries to dribble when there’s not a teammate around. This is common when players are adjusting to the reality of not being the clear-best player on the pitch like their youth days.

His own half losses were at 3.48 per 90, which is fewer than, say, Bruno G and Casemiro, but is more than Rodri, who attempts twice as many passes (though against lower-intensity presses). Whether or not he can cut that down as his volume significantly increases (and his teammate quality increases as well) is perhaps the most significant question that hovers over him.

On the other side, he’s good at drawing fouls when he’s caught, and PFF rated him the 4th out of 158 midfielders in ball carrying.

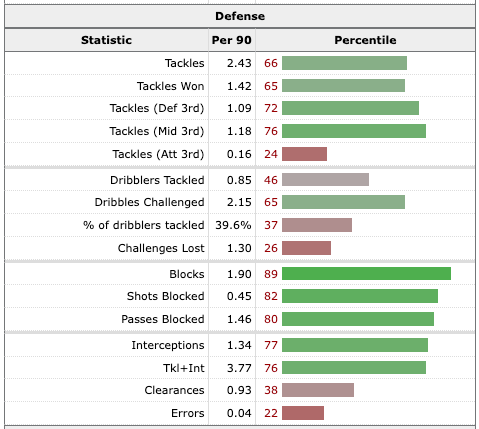

Defending

Drawing from the influence of Fernandinho, Lavia has a high trajectory on the defensive side. He is feisty, direct, balanced, and aggressive — though occasionally, a bit leggy and overambitious.

He won possession 7.5 times per 90, which was the highest rate of all Southampton players and a mark that only 14 other Premier League midfielders could better.

He goes in hard most times, and as we’ve covered, is mostly successful when doing so — particularly when the play is in front of him.

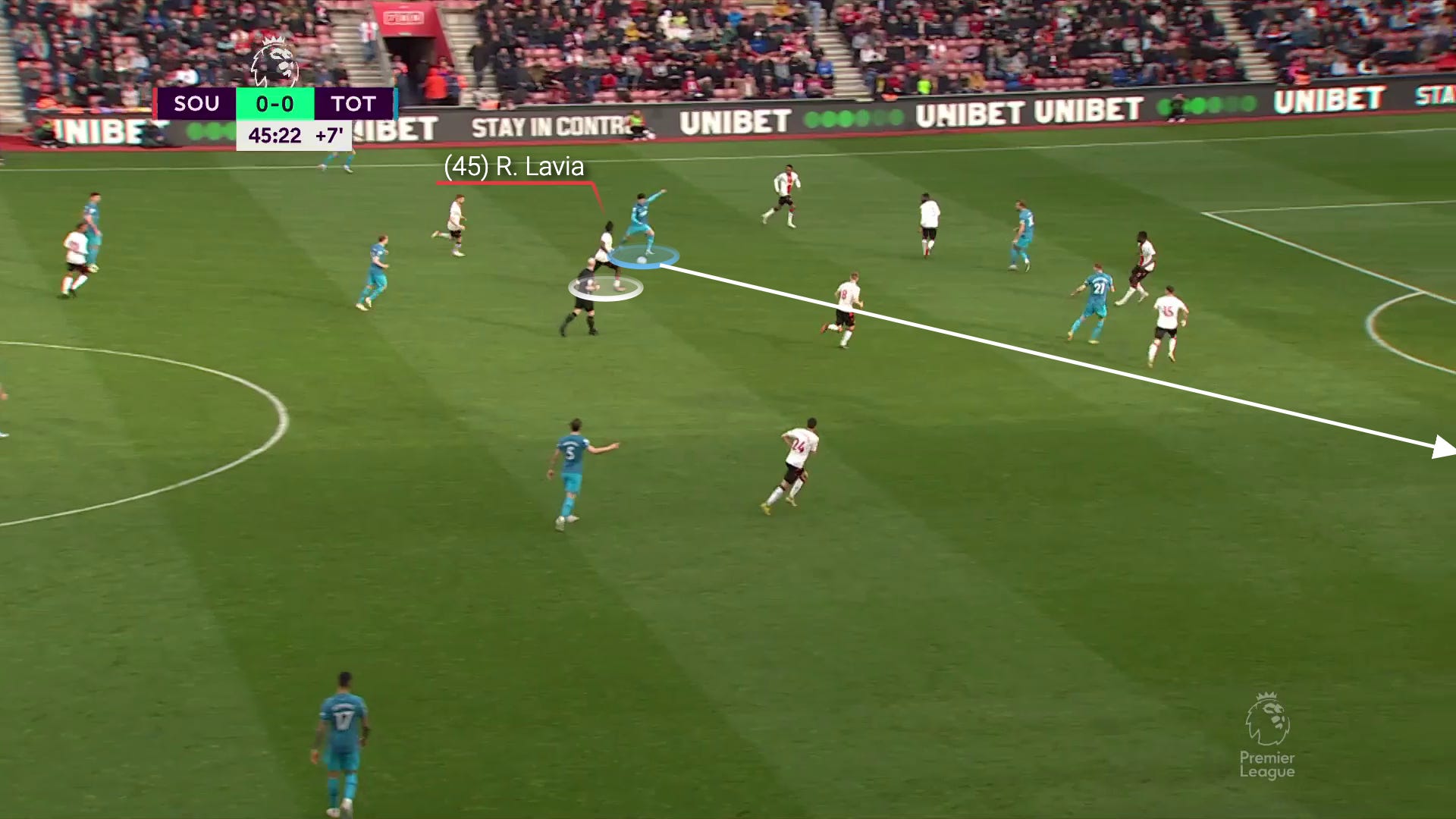

The late-season 3-3 game against Tottenham showcased the whole experience.

Here, he picks Kane’s pocket on a dribble, and carries it the other way:

That’s a very indicative challenge for him: face-up, aggressive, leg-stickin’, and usually successful.

This example of him hassling Kane back to his goal was kind of entertaining:

But once the play goes past him, the results are more mixed. He can play with more careful of an overall outlook. While he generally succeeds in identifying runners, though not always, and is fast enough, he hesitates to put his leg in (as he does on more direct challenges).

On this one, the ball was played around him to Son — and while he could have caught up and closed off this pass, he gave Son enough space to deliver this assist to the sprinting Porro:

In the box, he can be very careful, letting the CB’s do their work, and not looking to throw in legs and risk a foul.

Here against Wolves, he watched a few of his teammates struggle to contain a situation that, in fairness, they should have handled. Some messy bouncing balls resulted in a goal:

At 5-11, he doesn’t quite have the domineering size of a Rice, Rodri, Casemiro, or Tchouaméni. He also wins only 41.2% of his aerial duels, and attempts fewer than one per game. He seems to have the base and athleticism to succeed in the air but hasn’t shown it yet.

By and large, his work-rate, aggression, and baseline judgment is tremendous. His defensive ceiling in a higher-possession, higher-pressing side is astronomical. He has few struggles with the ball in front of him, but for a team that needed a “sitter,” he got sucked around the pitch a little too much while covering the wide acreage; it was a little too easy to exploit his aggressiveness when no one else was around, forcing him to get behind the ball and perhaps lose a runner.

That shit’s hard. Rodri was still working through this as a 25-year-old. As Pep said:

“Last season he moved too much. The holding midfielder has to be there, don’t move — be there. He’s getting better reading the situation and defensively he has more presence.”

Lavia himself used one of his idols to explain how he’s working on this:

“Fernandinho knows what he’s doing,” said Lavia. “He doesn’t run just to run. He’s like the brain of the team. When you’re young you want to run — left, right — but he knows what he’s doing so he won’t run as much but will still be effective. That’s something I keep learning from him.”

He’s still learning.

Lavia’s readiness

Here’s a word I try not to use: “raw.” Why? A younger player is not necessarily so.

When Lewis Hamilton entered Formula 1 and slotted directly into a top seat alongside a two-time champion, was he raw? Compared to his future self, sure. He would go on to grow leaps and bounds in technical knowledge, racecraft, and composure. But you know what else he was? Fast as fuck. Faster than virtually every driver alive.

(If you’d prefer to swap out the example of Max Verstappen, feel free).

To be sure, some players simply aren’t ready and necessitate further development, and it’s easy to underestimate the difficulty of a big jump. But in the case of guys like Camavinga, Tchouaméni, and Caicedo, among others — a player is not automatically below the required level just because they are young and have more growth to offer.

In fact, depending on their current baseline, they can offer a best-of-both-worlds: better production than many of the “readier” versions in the short-term, despite a few mistakes, and a sped-up trajectory towards maximum potential from then on. Lavia strikes me as occupying that tier.

Put another way: would you rather have a young Lewis Hamilton crash a couple cars, win a bunch of races, and challenge for the championship as a rookie — or a more experienced driver who can safely deliver you fourth place?

Kalvin Phillips may still turn out well for Man City — I have a feeling he will, honestly — but I can’t help but wonder if Pep regrets underestimating the younger mint.

(Editor’s note: Just as I was going to schedule this post up, I saw that James, the legend from gunnerblog, posted a brilliant video on Arteta’s obsession with ‘youthful experience,’ and the false choice between youth and rawness. Here it is…)

A 19-year-old from the Man City system with a full year of Premier League starting experience under his belt may just fit the bill.

Back in January, I created a new bullshit stat called “D.U.E.L.S." to sift and rank 80 potential defensive midfield targets on dozens of underlying metrics for defending, passing, dueling, versatility, value, creativity, age, fit, league-adjustment, etc. Rice was first by a mile, followed by some other stars and potential targets.

Many were surprised to see Lavia already up in eighth:

After an initial set of more proven, can’t-miss players (Rice in a first tier, then Caicedo/Zubimendi in the next), and a speculative group of likely-unavailable stars (Tchouaméni or Camavinga, come to the carpet), I would currently rank Lavia first among remaining targets at DM.

If all four current Arsenal options at DM return, my eyes would drift towards a more 8-y player like Koné, Thuram, Locatelli, or Koopmeiners. My greedy side wants one of them in either case.

From there, the question turns to minutes.

Do I think Lavia is ready to be the locked-in, every-week starter for a team with such ambition? No. But in the event he comes to Arsenal, that won’t be the expectation. If his arrival does indeed spell the end of Partey’s time here — the two seem interrelated — I ultimately think that a trio of the always-available Rice, Jorginho, and Lavia is sufficient depth for a real title challenge; Arsenal just launched a title challenge in a season they set forth with Partey, Elneny, and Sambi. While Jorginho can serve as a human safety net in the event of injury, Rice can flow into different roles depending on matchup, and I think Lavia is capable of earning significant, meaningful minutes. In fact, I don’t think he’d come otherwise.

Eduardo Camavinga provides a useful example. As an even earlier-developing freak-slash-prodigy, and more advanced profile, Camavinga was able to earn a role in a Champions League winning side as an 18-year-old. That year, Real Madrid played 56 games total across La Liga, Copa del Rey, Supercopa de España, and the Champions League. Camavinga started 17 times, and made 40 overall appearances — which was the minute equivalent of 19 full-90s across 56 contests.

Lavia is a year older than Camavinga was then, but possesses many of the same mature characteristics. I think that amount of action could serve as a worthwhile objective.

Role & Profile

What kind of player would Lavia be long-term? Well, I’ve now spent several weeks talking about “triple modular redundancy,” and how a player’s overall profile and dynamics are more important than locking them into a particular position. Arteta and company are clearly looking for flexible profiles that work in multiple roles across the pitch.

In this case, though, I’ll zag. After watching all this tape, Lavia strikes me as a fairly prototypical incarnation of a modern deep-lying playmaker. To understand why I say this, consider this recent quote from Zidane:

"Football today, physically it has changed a lot. In my time you can be less well physically it was not a big deal you could get out of it with your technique. Today, physically, it might have played tricks on me.”

A player like Lavia, then, is part of the sport’s inexorable march forward. You take a previous generation’s best technical examples, and you add more physicality, training, and athleticism — not to mention, more historical context to draw upon.

With that, Lavia is a different profile than some other modern defensive midfielders, whether we’re talking Rodri, Rice, Casemiro, or Tchouaméni. His on-ball inclinations are more that of a regista (as explained well here). For the uninclined:

The regista is a creative player who operates in front of the defence, almost always in a central position, and looks to get on the ball as often as possible. They are responsible for providing the link between defence and attack, and controlling the tempo of the game through their passing. The regista is also known as the deep-lying playmaker: they retain their deep position and dictate their team’s play with their distribution.

The purest example of this role in football history is Pirlo, who’d gather the ball from the backline, recycle it or carry it to a place of his choosing, and flawlessly ping it all over the pitch — directly creating attacks out of thin air through a variety of switches, line-breakers, and swoopers to the line. Think back to that through-ball to Armstrong from earlier in the post, and how comfortable Lavia was in that area further back.

Lavia has got a bit of the “it” factor when it comes to confidence against a press and all the requisite subterfuges and changes in tempo. It’s also nice to envision the Pirlo over-the-toppers landing at the feet (or heads) of Havertz and Martinelli, among others, and a wide passing range against low-blocks.

But Pirlo was afforded space, and his defensive limitations were offset by skilled wreckers like Gattuso. In England, there have been doubts about whether such a regista could truly succeed in a league that is so physical, rushed, and efforty, as was brilliantly covered in this video by Tifo.

The best example of a modern regista, though, currently plays in England. He plays for Arsenal, in fact. His name is Jorginho. He has survived and thrived in the Premier League by combining aspects of Pirlo’s game (including the slowness) with higher defensive awareness and intensity, not to mention excellent complementary partners in the midfield. It’s certainly worked, and one can see how Rice may be a Giant Kanté to Lavia’s Jorginho.

Lavia, to his credit, is showing some early signs of Jorginho’s intelligence and temperament. There are also comparisons to be made to the likes of Thiago and Kovacic, and I wouldn’t put his potential as an 8 totally off the board. But his savvy doesn’t seem to extend to more advanced areas at the moment, and that’s where some of the aforementioned “0’s” in his binary passing game show up. I don’t personally see any potential as an inverted full-back yet, either: he looks best through the middle.

I’m not too scared off by his height at 5-11 (especially with his own strength and balance, some mountainous CB’s behind him, and a potential pairing with Rice), and to me, he’s most exciting as the answer to a rhetorical question: what if Jorginho had a healthy dose of Camavinga’s athleticism?

Yesterday, I sketched a few options of using Rice in build-up. Aside from straight-subs in cup games and the like, I think the rightmost image is the best way to envision Lavia’s potential as an occasional starter with the big boys. They can even swap around like you may have envisioned Rice and Caicedo to do:

Defensively, a midfield block with Rice and Lavia would be pretty nasty.

Which brings me to my next idea for his usage in the short-term: as a Camavinga-style “impacter” sub in the LCM spot when protecting a lead, turning it into a left-DM, or as an actual depth option there as he eases in. With the likelihood of Arsenal using some “Twin 10” configurations to secure goals, the idea of gaining a lead and then having Lavia come on for a Havertz, ESR, or Vieira is very appealing: he can partner up with Rice and run around, press, disrupt, add solidity to the block, and contribute to “death by 10,000 passes” as well. Their double-pivot would allow Arteta to sub see the game out with a 4-CB configuration as needed (in a 4-4-2 in possession and out), and with transitions possible, Rice and Lavia could play long-balls over the top at will.

He’s very young, it’s true. He’ll need to be supported tactically, where Rice could be a big help. He’ll need to learn to sit more centrally and do less at times, which will help the play stay in front of him, where he’s best. He needs to dramatically improve in 1-2 passtypes, and perhaps dribble a bit less and carry a bit more. He should be playing with the best players available so he can rise to their level.

But that’s all inherently coachable. It’s also true that his raw self is more impactful than the fully-manifested versions of many older, safer players. He’s ready to play.

The ceiling is high, and the immediate floor is not as low as you may think. It’s simply not normal to be this good, this young. With top-6 suitors swarming, it’s time for Lavia to bet on himself once more.

'And it's Edu's BBQ put through by Billy Carpenter would you believe it! That sums it all up!'

with a name like Romeo Lavia, you know he has...skills