Five ways to improve Arsenal

Arteta implored us not to be satisfied. In that vein, we turn the opposition scouting tool inward. The result is a huge essay on the specific ways the team can still get better

There are two stages of processing this point in the calendar year.

First, you take stock of the season.

Then, you transition into full transfer market sicko mode, slamming F5 to refresh accounts and websites you know for certain are unreliable. The goals and drama are behind us — we need something, anything, to feel alive.

Many of us skip the first step. If this poll is to be believed, it’s enough for a quorum.

After much deliberation, I have decided to break the first rule of newslettering and ignore the expressed wishes of the reader. (Perhaps more accurately, I am defying the expressed wishes of the more dopamine-addled Twitter user, where this poll was housed.) This is because I believe that to successfully approach stage #2 (transfer szn), one must have their head fully wrapped around stage #1 (a post-mortem).

How do you take stock?

The first and most obvious way: it was a resounding success. The season resulted in a spate of records, including the highest win percentage in Arsenal history, the second-highest points haul in team history (after the Invincibles), and the most wins in the Premier League era. Our Arsenal boasted the clear-best out-of-possession side in Europe, and against the so-called “Big 6” of the league, Arsenal never lost once (6-4-0); including the Shield, Arsenal were never defeated in three matchups against Manchester City.

This, from the wonderful DataAnalyticEPL, shows how superlative the defending was.

It was a clear step forward.

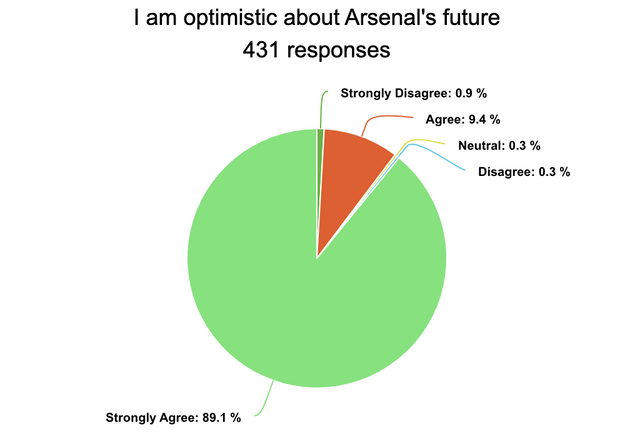

In a different survey — this time of Reddit users, you beautiful people — and utterly scientific, thank you very much — it’s obvious that people are feeling pretty good.

It may not be the best use of a time machine, but if one could flick the big red switch, one could return to the autumn, and one could tell oneself that, by year’s end, Kai Havertz (98.5%) and David Raya (96.4%) would be almost universally viewed as successful signings.

Be sure not to enter the portal empty-handed. Your past self will require proof.

I am, however, not here to write a long article about how great Arsenal’s squad looks. I ultimately summed up my personal feelings on the season with four words: “So grateful. Still greedy.”

Arteta said something similar right after the last kick.

“All this is happening because you started believing,” said Arteta. “You started to be patient, you started to understand what we were trying to do and all the credit has to go to these amazing players, and the staff that are unbelievable. I think now it’s time to have a break, think, reflect and please, keep pushing, keep inspiring this team. Don’t be satisfied because we want much more than that, and we’re going to get it. Thank you so much.”

Arsenal are ideally set up for the future. With big sides rebuilding throughout Europe, we have the great fortune of supporting a club that serves as a shining example of the right way to proceed.

But progress is not perfunctory. Maintaining a trajectory is difficult at the top, especially when discussing the final marginal gains that decide titles, and especially when comparing oneself to a bylaw-flouting petrostate behemoth with Pep Guardiola at the helm.

Regardless, it’s time for some fucking trophies. So we must take stock.

How do we do this with the level of dispassion required? One person who can answer the question of how to take stock more literally — what goes up, what goes down, and why — is Aswath Damodaran, a professor at the Stern School of Business at New York University. He studies and teaches on the topic of valuation.

Bear with the analogy, but I think this is a helpful way to look at things.

When you value a company, you say well, “they’re going to do this, it’s amazing, that’s going to increase their growth rate.” But what if everybody else does what they do?

We need to bring in some game theory into valuation and realise that when companies make changes, the rest of the world doesn’t just sit still and let them do it. They respond.

It’s a mistake I see analysts making on growth rates often. We know conclusively that analyst estimates of growth and earnings of individual companies are biased upwards. Why? Because they look at companies, see all the special things the company does, they listen the management, and they give it a high growth rate. But if there are 15 other companies doing the same thing, they can’t all grow at that rate. Because the market is not big enough.

You’ve got to build in those responses when you value companies. It makes life a lot more difficult. But it makes it much more realistic.

The mistake is to assume that Arsenal are the only smart ones around, or that the club’s methods will not be copied, or that things will improve indefinitely as a matter of course, or that it’s easy from here. Life doesn’t work like that, and this club has myriad examples of careers taking winding turns when a more linear path once seemed certain. I don’t know how many would have predicted that Martinelli would go from 15 league goals last year to 6 this year.

Before I freak you out, football is different than the global economy. There are fewer stakeholders, fewer inputs. Stable, lockstep, proven football apparatuses (with the ledgers to match) are exceedingly rare. There are only a few dozen players alive who possess that final level of gravitas to put you in the position to win the biggest trophies; the clubs that acquire and develop those players will always have a moat around their castle. You can scour your spreadsheets for a “Saliba type” all you want, but we have Saliba.

Meanwhile, there are even fewer world-elite managers.

Evidence sure seems to support the idea that Arsenal have said football apparatus, players (mostly), and manager. That is, in fact, fairly durable.

But as tempting as it can be just to stay the course, the task at hand is always a bit more complicated. We saw that with the departure of Granit Xhaka, who himself went invincible at Leverkusen, and solidified himself as the most progressive force in Europe.

While it may have been more comfortable to run it back with Xhaka, or try to replicate the dynamics of the previous season with a more similar profile, it was more difficult — but more necessary — to change. The opponent is not static. Yesterday’s price is never today’s price.

This kind of dilemma is discussed in the Steve Jobs biography.

One of Job's business rules was to never be afraid of cannibalizing yourself. “If you don't cannibalize yourself, someone else will,” he said. So even though an iPhone might cannibalize sales of an iPod, or an iPad might cannibalize sales of a laptop, that did not deter him.

(My self-conscious brain implores me to tell you this: I don’t read such hagiographies uncritically. But it doesn’t mean there aren’t a few interesting kernels to grab.)

If you’d prefer a more modern way of describing what I’m talking about, here’s a tweet.

im so ruthlessly commited to Dialectics that i am constantly at war with the person i was two days ago, who is a clown and a coward

Continuous improvement is a long road. Stasis is a risk in itself.

In the early days of the season, I led with an Eric Hoffer quote.

"In times of change, learners inherit the earth, while the learned find themselves beautifully equipped to deal with a world that no longer exists."

OK, enough with fuckin’ quotes.

Let’s dig in.

👉 Looking within

For this post, I won’t be excavating specific losses, or explicitly discussing who should be signed this summer. I’d like to look at things on a more holistic team level to understand where Arsenal may improve next year.

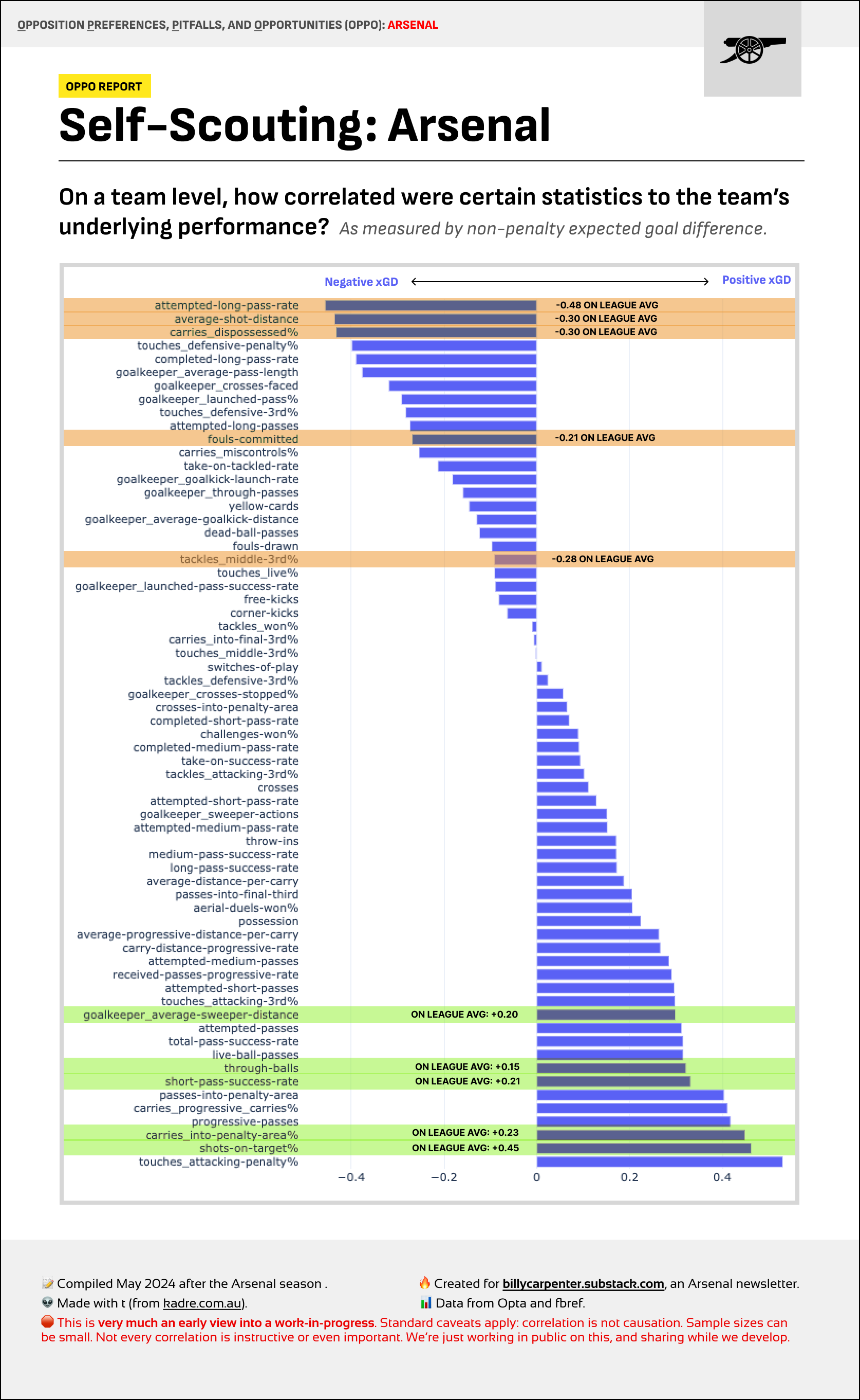

To do that, we begin with our scouting tool, which is now tenuously called OPPO: Opposition Preferences, Pitfalls, and Opportunities.

I’ve worked with a brilliant statistician named t (from Kadre) to bring this to life, and we introduced it against Man City. Here’s the overview from then.

To oversimplify, I’d wanted to do some correlation studies to see which statistics — be they individual or team-level — had the strongest relationship with the underlying performances of specific opponents.

For instance, if you learn that disrupting a certain kind of pass, or restricting a certain player’s carry, is disproportionately pivotal to a team’s performance, then you can use that to focus your film study — and, ultimately, your gameplan.

Here were the caveats:

Correlation is not causation. Just because something happened more frequently, it does not mean it caused the underlying xG difference. “Just stop them from getting corner kicks and prosper!” is not the takeaway here.

Not all correlations are instructive or even important. It’s not all that useful to learn that teams tend to win more games when they shoot a lot. Key passes, assists, touches in the attacking third — these are all likely to come from dominant performances.

There are sample size limitations and general noise, particularly on statistics that don’t happen at a high volume.

Out of silly competitive paranoia, I didn’t want to share the findings on Arsenal during the season.

That changes now!

In orange and green, I’ve highlighted 10 stats that have the highest negative (orange) and positive (green) deltas from Premier League averages. This should give you a sense of what may be particularly important to Arsenal’s performance levels.

On a team level, there are a few things that pique interest:

Obvious alert: Arsenal did disproportionately well when they passed short and forward. Conversely, the more they went long, the more they struggled. Arsenal didn’t necessarily employ a lot of big-space passers, and were short on big-space runners. Arteta may steer them away from such passes in any case.

As such, Arsenal did better the more the ball was in play; interrupted games with more fouls and delays were more difficult to weather. This is common among teams who are qualitatively superior. When there are more plays, there are more chances to show you’re better, and bouncy variance matters less.

Anecdotally, Arsenal could sometimes take a bit of time to find their rhythm, manipulate the block, and settle in. When games were interrupted, that rhythm was more difficult to find.

Shot quality (and distance + general lack of difficulty) was very important to Arsenal success. This is the opposite case for Man City. We’ll cover that in a bit.

Dispossessed carries — that is, times that Arsenal players were stripped without trying an actual take-on — were an indicator of struggle.

Tackling in the middle third — that is, engaging in an actual tackle in the middle of the pitch — was tied to poor performance.

Now, let’s check it out on a player level. Here is a curated top-15.

Some takeaways here:

When he played well, Martinelli was quite impactful. Specifically, his carries.

From what I can tell from looking at further underlying numbers, Saliba/Gabriel/Rice were able to provide much of the stable floor for performance that we saw throughout the year. After all, Arsenal were only demonstratively “outplayed” a few times all year. From there, the variance was largely a product of the attack.

There is ample support in the data for why opponents give so much attention to Bukayo Saka. I would offer the hypothesis that Arsenal are especially dependent on his ability to move defenders around; when that doesn’t happen successfully, the opponent block is especially settled, and Arsenal don’t have enough options on the 1v1 dribble to compensate.

“Martin Ødegaard take-on success” being the #1 indicator seems a little noisy to me. That said, we know what it’s like when he’s feeling himself: Arsenal are 20-5-1 when he’s tackled one or fewer times.

Interestingly, the more Raya had the ball, the worse the team fared. I think this is similar to what we saw with Onana in the Manchester United report. It’s not an indictment of the keeper. It’s more indicative of other factors: namely, more touches for Raya probably means that the team is trying to build out from the back but not successfully cutting through.

There plenty of other data points you can use to confirm your priors. 🤪

When I saw that Jorginho’s passing into the penalty area fared well in the underlyings, I immediately thought of the Liverpool matchups — which featured some of the most promising (and portentous) dynamics of the year, to my eyes. Jorginho was in the double-pivot, but not usually the deepest midfielder, and was especially aggressive and line-cutty because Rice was generally behind him.

This shows up in his pass map, which was pretty direct.

I said I wouldn’t talk about transfers, but looking at that screenshot above and imagining the possibilities with a Bruno/FDJ type in that left-8 and a Timber/Hato type in the LB spot gets me feeling goooood. I struggle to find weaknesses on paper.

So what are some of the specific areas in which Arsenal should improve?

1. Improve Plan B

Let’s start with the right.

The right wasn’t necessarily firing all year, despite some great early individual efforts from Saka. This is largely because Ødegaard was parked near the box, often getting shadow-marked in the process, while White would stick behind to improve the rest defence, overlapping in moments. That all changed in December, as we’ve covered at length.

Here’s Jordan Campbell in The Athletic describing the change.

White has been given the licence to overlap and make late sprints forward to support. Saka has been given the freedom to vary his starting position, while Odegaard’s role has been changed from that of a second striker removed from build-up to a complete midfielder orchestrating the play from deeper.

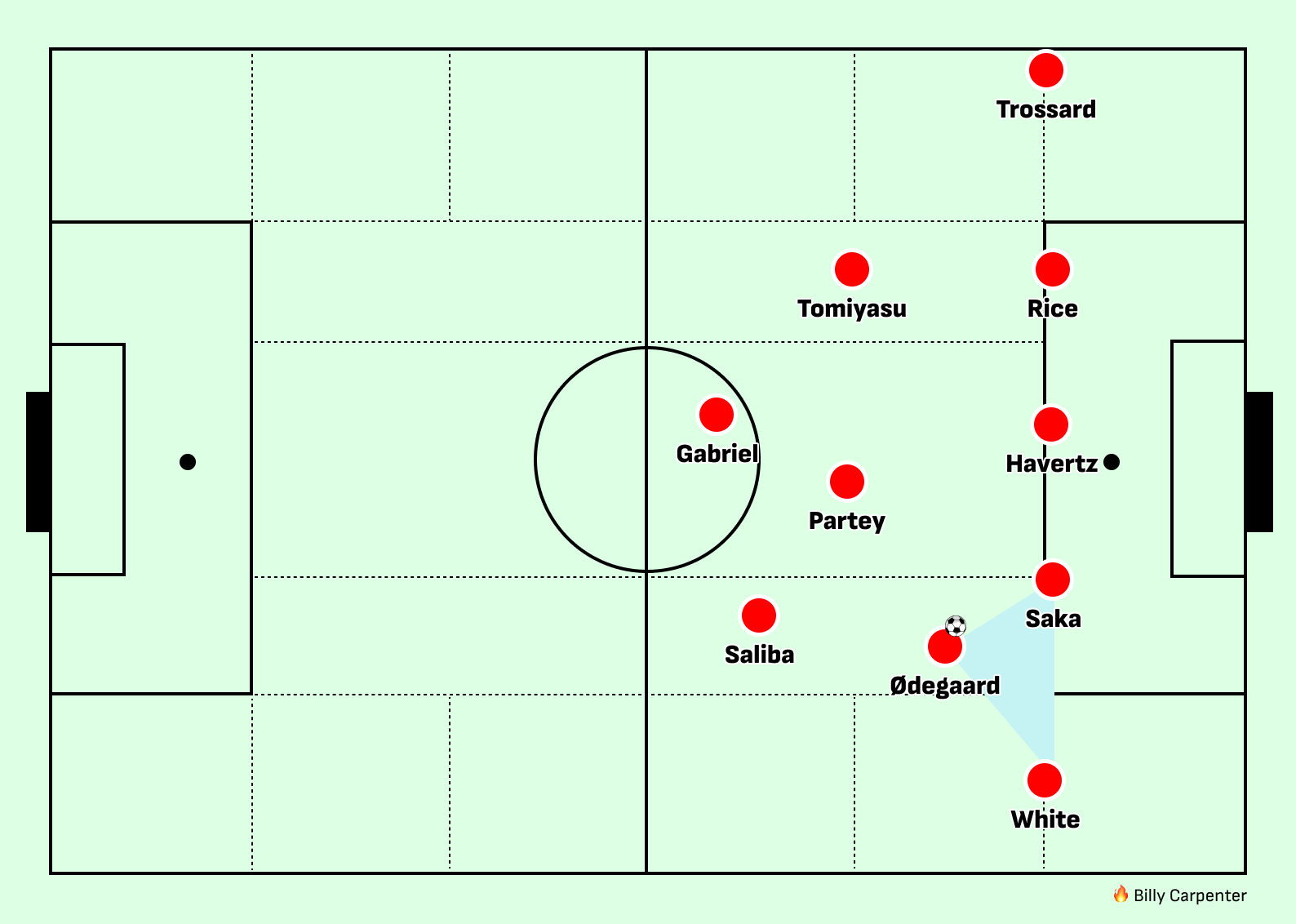

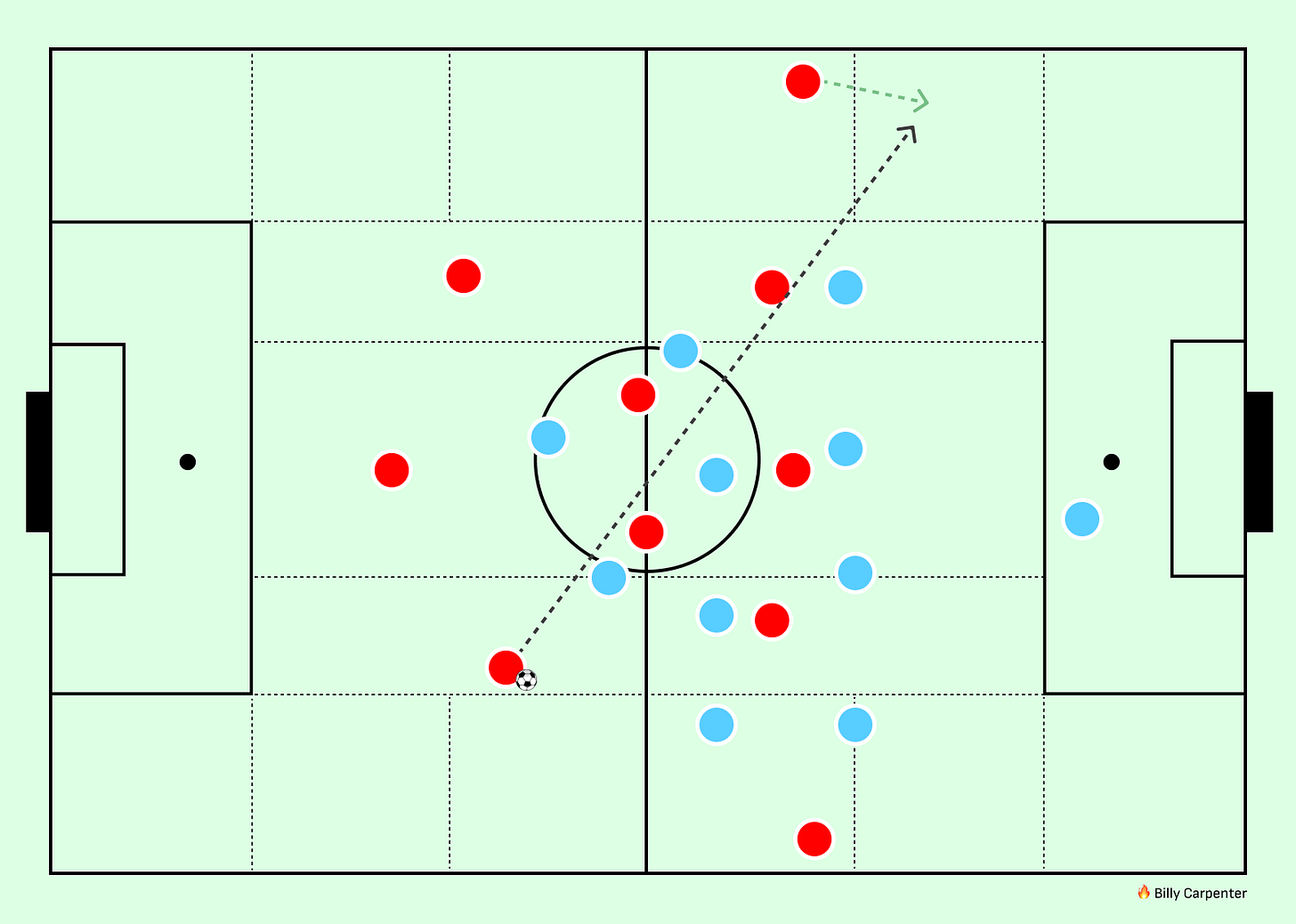

This right-sided pod started getting more dynamic. I thought it usually looked best in the below configuration, where Saka can pinch in and obtain more access to the goal.

Saka wound up leading all of Europe in touches in the penalty area. It wasn’t always in the most dynamic situations (given how far teams shaded to his side, and how many made him their primary concern). Still, the locations of his touches were rock-solid, and his gravitas had huge impacts throughout the pitch.

As this triangle started going brrrrr, Arsenal would overload the right, with Saliba increasingly joining the party. This side was full of stability and availability throughout the campaign and would go on to lead the world in most creative statistics.

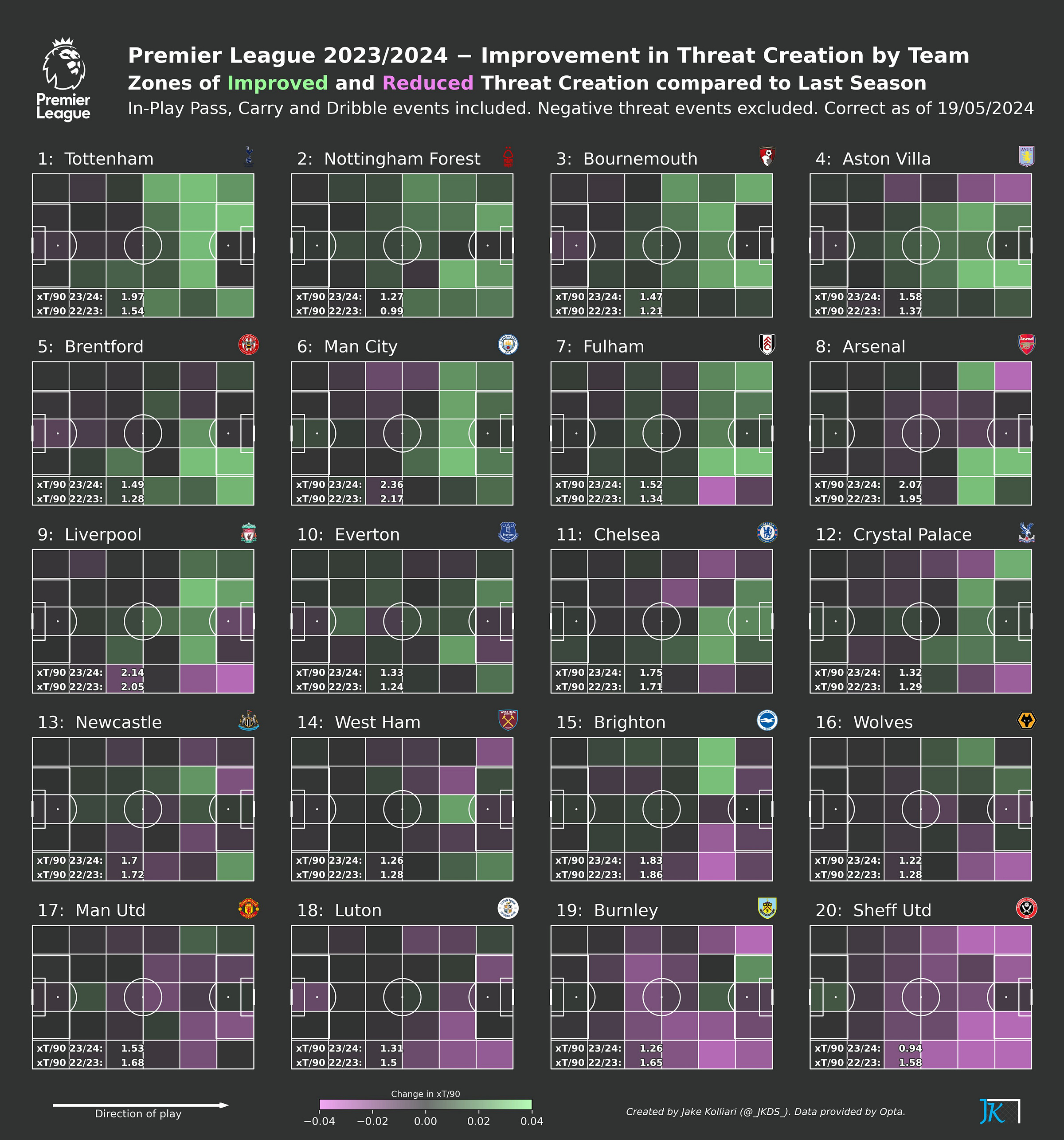

In threat creation (gosh, this work by Jake Kolliari is a fucking gold mine, read it and follow him), you’ll notice that the team, much like your uncle, has become decidedly more right-leaning.

Here, you’ll see that WhoScored attributes 41% of the attack to right.

Now, let’s take a step back. We hear a lot about balance, but we have to decide how big of a “problem” this is, really. The objective is not to create a perfectly egalitarian balance in touches throughout the pitch; the objective is to score as many goals as you can. Balance can help with that, but our pixel-perfect passmaps won’t get us into heaven.

Here’s a hypothetical. You’re a manager and, through a series of unfortunate events, you are forced to start a limping 58-year-old chainsmoker at right-back against Kylian Mbappé. In this scenario, what will give you the poorer night’s sleep: the idea of Mbappé’s team dinking it around, trying to achieve perfect balance? Or the thought of Mbappé getting the ball and going after your guy 40 times in a row?

I know what I’d choose.

To some degree, that’s what has happened with Saka. I’d argue he’s our best player, and he should be fed as such.

And so I rise to defend the idea of right-sided overloads, followed by box-crashing from the left, as a Plan A. I don’t care if the passmaps are balanced. We saw Trossard rain a healthy amount of goals in this way, whatever his other shortcomings.

But what happens if, as we saw in the OPPO report, Saka is dispossessed and nullified? The job, then, is to create a better Plan B.

Arsenal didn’t do so, especially early in the year. Jesus was hurt, and Eddie Nketiah came in his place. What resulted was the appearance of a Martinelli/Havertz/Nketiah left side, which didn’t effectively platform any of the three. The struggles were masked by defensive insanity and set play brilliance.

This is not the fault of any individual player. Martinelli was working to figure things out; Nketiah found the crowded space and increasingly-deep (and giant) defensive lines hard to exploit; and Havertz was at his most conservative and least dynamic.

What resulted was a lot of stuff like this. You’ll see how three poachery players all have the same impulse in such a moment.

That’s stinky for all involved. The overlap in their positional instincts was too much to overcome — do Nketiah/Havertz want to go out to the left-wing, really? — and wasn’t offset with effective take-ons or passes.

The circumstances lined up poorly for Nketiah, a player I believe is capable of chatting with several 15-goal Premier League strikers on skill; I’d expect him to join their ranks next year. The opposition dropped increasingly low, which deprived him of channel opportunities; for much of the year, Arsenal faced the lowest average defensive actions in all of Europe. This meant two huge, athletic CBs were on his shoulder in most situations. He followed up a Spurs game in which he had 6 completed passes with an Everton game in which he had 10 total touches.

When you’re defended like Man City, it isn’t easy to find space without a sufficient advantage in height or burst. Combine that with poor service from his midfield — Rice and Havertz were learning the ropes, perhaps out of position, and Ødegaard was shadow-marked — and his season probably didn’t reach his expectations, despite him being the fucking man.

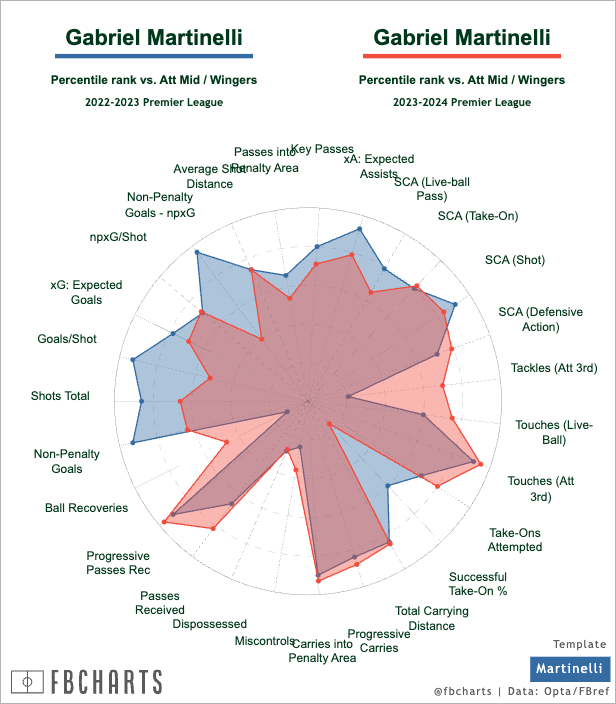

All of these circumstances impacted Martinelli as well.

He’d often ferry the team up the pitch, encountering a double from there and generating a lot of corners. This helped. But from there, he wasn’t well-served with stable partnerships on his side. This led to a lack of mind-meld fluidity and interplay, resulting in fewer through-balls behind and access to the middle. He responded by running, running, and running some more.

The timing of his season was annoying from his personal perspective. As soon as dynamics started improving, and Ødegaard started shepherding play throughout, and actual midfielders were in the left-8, Martinelli was battling some knocks and Trossard had rendered himself undroppable.

Later in the season, with Ødegaard sitting atop a defensive double-pivot, the captain was able to venture leftward with more sagacity. This kind of Ødegaard passmap would have been a sight for sore eyes for much of Martinelli’s early going; instead, Trossard reaped the rewards later in the year.

Earlier this year, I looked at how the void of Xhaka had impacted Martinelli. What I found was that Xhaka did indeed help a lot with this “Plan B” (or even Plan A) progression, and gave Arsenal more credible build-up through the left — but as far as pure goal-scoring, Martinelli was much more likely to get his numbers through other means — namely via a) transition with other players and b) passes directly from Saka (i.e., box-crashing).

This all led to a season that was perhaps less of a step back than many would perceive. Looking through the data, he’s improved or matched his previous campaign in most statistics. He was just able to score with less frequency.

Martinelli was reliably able to drag the team up the pitch through his carry; this shouldn’t be taken for granted. We’d like to see those shots go up.

Moving forward, this left pod needs a few things:

More continuity so relationships can develop

More credible width-holding from either (or both) LB or LCM

Some more dynamic passing range and 1v1 take-on ability from this side

Ideally, you sign an LB who can credibly play in all three of thee points in this triangle; I personally don’t think this has to be a pure overlapper, because that can result in the scenario with both full-backs holding width, and that can be a little open in transition. Your CM (Rice or another) should be able to do the inside two at least; all three would be ideal.

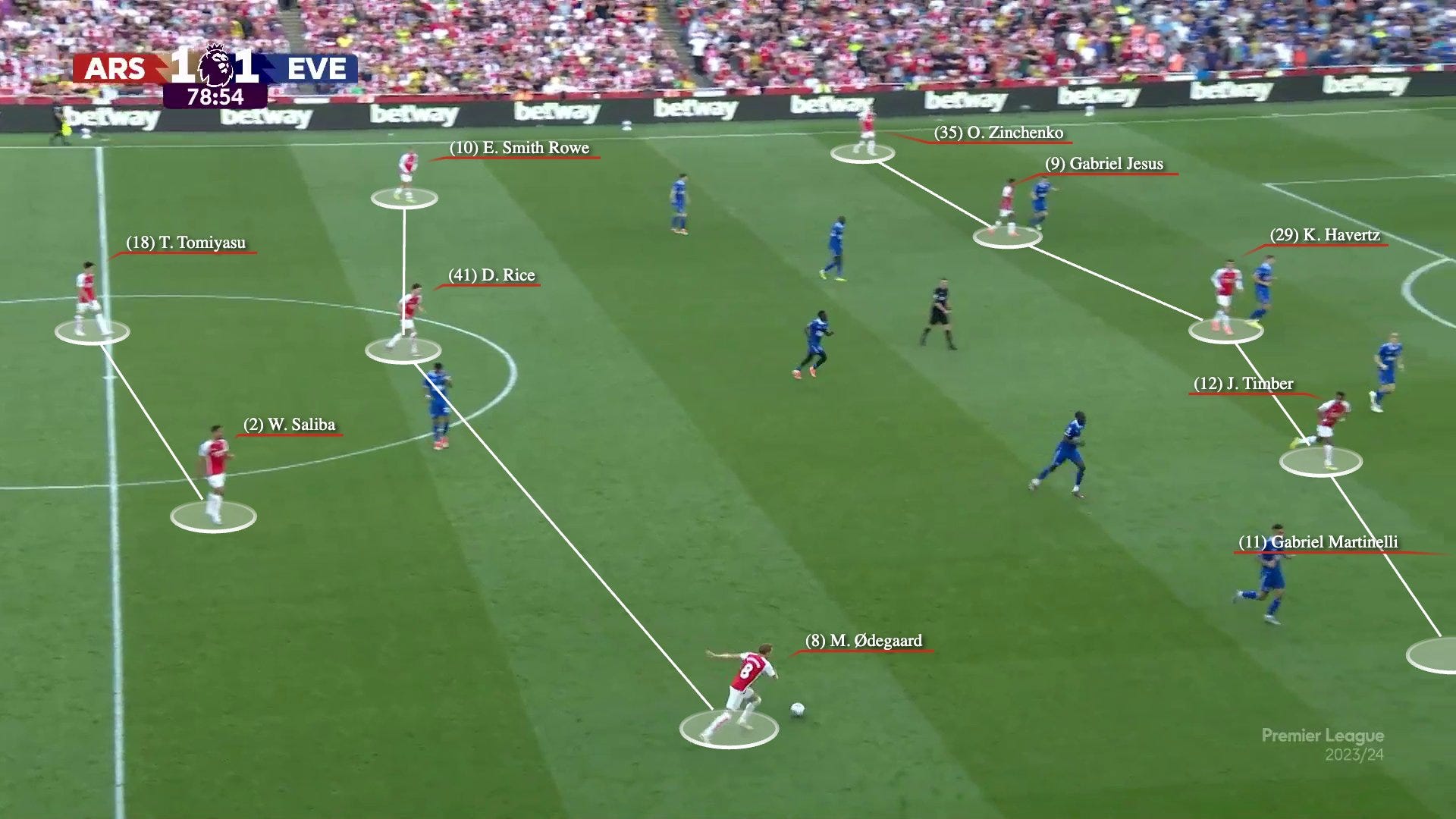

From there, you get exciting opportunities like what we see below from the last game of the season. Jesus (LW) is pinched in, which would also make Trossard/Martinelli (or a Šeško???) happy; Zinchenko is high at LB, and we can potentially imagine a slightly more wingery, crossy presence out there; the LCM (Smith Rowe) in this case can drop down to either carry (Rice/ESR), rip apart via dynamic passes (Vieira), or both (Bruno/FDJ type).

Logically, this will grab some attention from Saka (though I expect that to persist). What may be underappreciated is how a better left side will allow Saka to cash in on some easier goals. Left-sided cutbacks could happen with greater frequency, and there’s no reason Saka can’t knock in these more, as a mirror image.

…and no, I haven’t fully written off the Havertz shadow-striker thing in certain matchups, particularly overpowered teams who are going to sit back. It’s easily forgotten that some of the bigger wins in January were with Trossard/Havertz interchanging up top. There just needs to be an intense focus on the surrounding dynamics, and how the profiles interlock with each other.

In sum:

Problem: Create a more threatening “Plan B” through the left. Turn the sides into “Plan 1A/Plan 1B.”

Solutions: More use of double-pivot midfield; Ødegaard floating horizontally; more stable relationships; one more credible width-holder (perhaps third on the priority list, behind CM and attacker); if Havertz is at LCM/SS, needs to either be at the tip of a 3-4-3 diamond or with a 9 who vacates the space

2. Increase risk tolerance in the middle

A team’s in-possession and out-of-possession strategies are inextricable. How (and where) you attack has a direct impact on how (and where) you defend.

There are many reasons to attack in those wide triangles:

It pulls opposing wingers down, dulling their transition threat

The middle is usually absolutely packed with defenders; the best blocks are almost impossible to move around

A ball loss is less threatening, as it’s further away from the goal. If you lose it by the corner flag, you can construct a series of booby traps (counter-press, counter-press, foul, delay, Saliba/Gabriel, etc).

A loss in the middle is more dangerous. It adds variance, which you despise if you feel you’re the better side

We saw the pros and cons of this with Thomas Partey inserted back in the lineup. His one-touch direct balls through the middle would often generate threat, but they could also generate transitions the other way.

As far as passing range at the #6, there were two ends of the spectrum: Rice (a little too outward-facing and conservative, though I expect that to improve), and Partey (a little too one-note and direct). Jorginho was the best at modulating this tempo, but obviously brings other disadvantages with him.

The more conservative bent took the majority of the year.

Below, for example, you’ll see how few times Arsenal are blocked on the pass.

But it’s not only the passing.

Arsenal are unlikely to engage on the dribble through the middle. Part of this is down to the profiles available (this is just not a strength for players like Havertz and Ødegaard), and part of it is down to a philosophy of not losing the ball too much here.

Meanwhile, their biggest rivals have loaded up on every dribbler they can find:

This success rate isn’t a proxy for quality. Vinicius is a 38% dribbler; Mbappé is 46%. This is more indicative of where a team decides to engage in these dribbles.

In the attacking third, dribbles are crowded but more likely to result in a goal, and a ball loss is less problematic — so the success percentages will naturally be lower. In the middle third, dribbles can be higher-percentage: see an opponent in space, beat them. The problem is that the losses are much more dangerous, and can be turned into counters in short order.

In the midfield, Arsenal are only really likely to attempt these dribbles when they’re already in trouble; the dribbles aren’t on their own terms. If they have space, they usually power-pass it out into the wings.

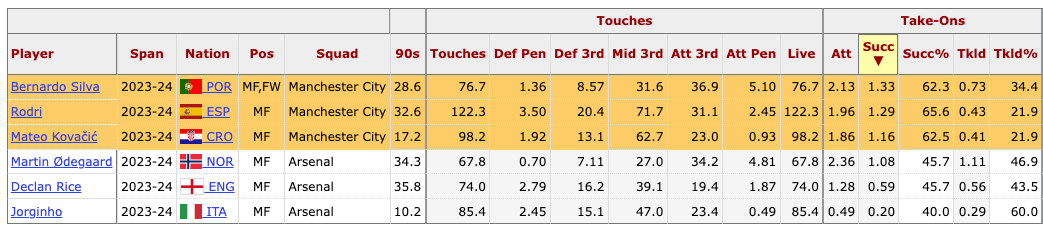

You’ll see the difference in philosophies below. Excluding a player like Foden (who would top this list), the example Man City players are top-three.

On the year, Declan Rice had 21 successful take-ons, while Rodri had 42.

This reliance on Saka to move players around led to those moments where things felt overly static and difficult to break down. I don’t like adding any expectation to a teenager, but our next wunderkind is pretty much the exact tight-space, confident, tekky, strong, central dribbler that you’d target to rectify this.

If Arsenal wind up playing in a double-pivot with four CBs, it feels like the risk factor can get turned up a little.

Problem: Not enough threat is generated through the middle

Solutions: Let Rice dribble more; bring in another carrier/dribbler; rely on a more defensively-solid LB to shield in case of a ball loss; unleash ESR (if not sold) or a certain next-gen starboy

3. Boost team speed

Here is, essentially, how Arsenal got knocked out of the Champions League.

Speed kills.

Some of this improved through the year. One of the advantages of playing Havertz at the #9 is that he can gallop more, and this decreases the reliance on Martinelli to provide that pace on his own. A little more space-coverage in the midfield (see Jorginho above) can also increase Rice’s risk tolerance in attack.

You can beat a so-so mid-block with dribbles. To beat the best ones, you need killer passers and killer runners. Arsenal don’t have quite enough of either.

Top speed is a noisy stat and we should be cautious about over-indexing it. But in the Champions League this year, no Arsenal player made the top 83 of top speeds. That player was Saliba (at 34 km/h). For reference, Antony was clocked faster than any Arsenal player this year.

Problem: Need more speed, especially to increase counter threat and runs behind a mid-block

Solution: Sign a runner or two. I’m a genius!

4. Add ball-striking

I have given Phil Foden shit thusly.

The objective of every Arsenal gameplan is to move heaven and earth to manufacture 30 seconds per game where Bukayo Saka is defended like Phil Foden.

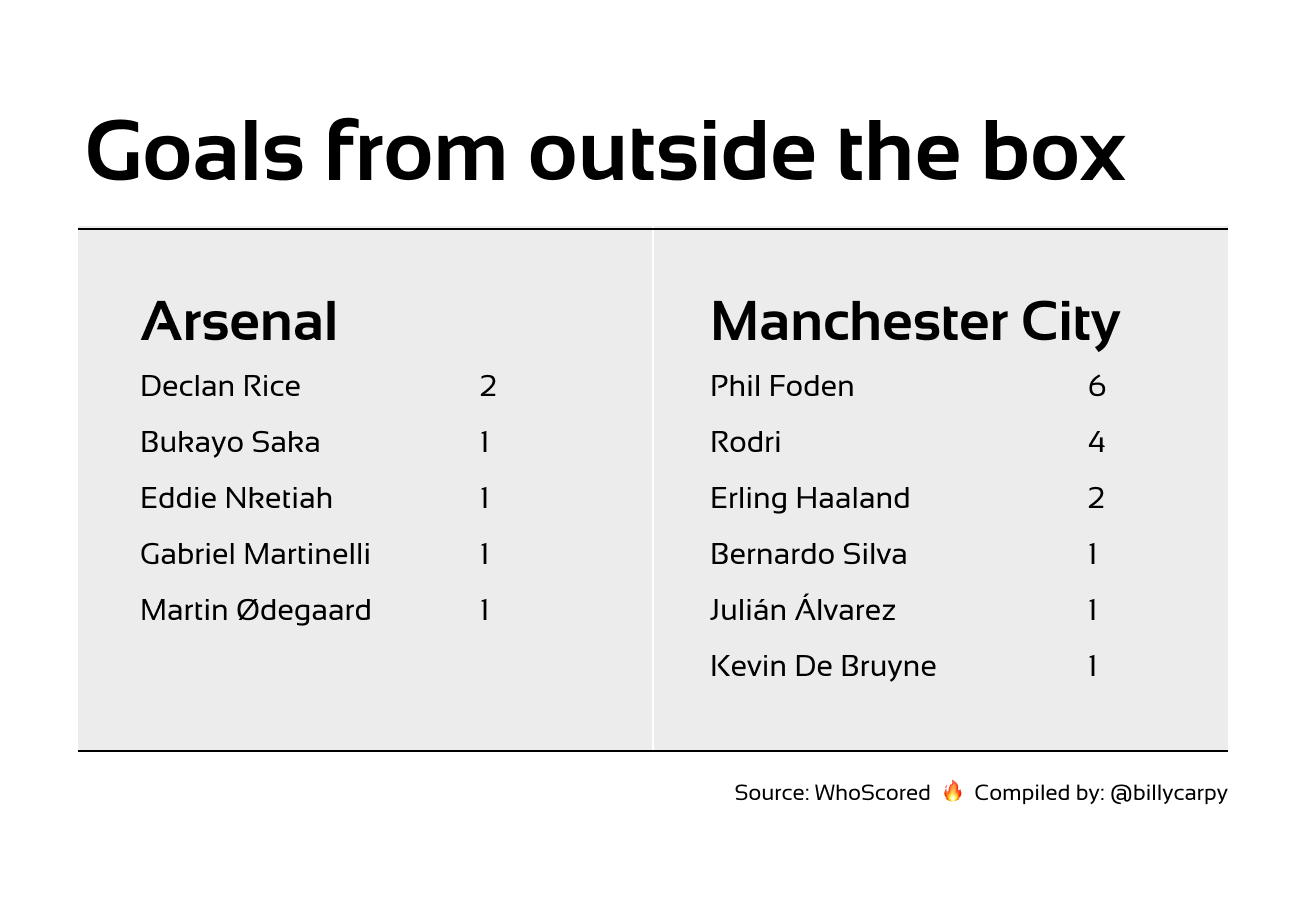

He wouldn’t be my pick for Player of the Season, but the truth is, he’s been great, and has had a major impact on the title race. This is for a fairly straightforward reason: as we saw in that final day, his ball-striking has been hugely influential to their season, always seeming to come through in the right moment. While running our opposition reports, Man City have been an outlier — they do better when they take further, off-target, “worse” shots. This is because they’re likely to get one in. If not, they at least generate a little chaos in the box.

Please, Phil, I’m trying to be a hater over here.

If you’ll remember, the 3-3 match between Real Madrid and Manchester City was, essentially, a banger competition.

Arsenal have had their own experience with this.

In the first half of the season, Arsenal underperformed their xG by -1.9, indicating worse luck or worse finishing.

In the second half of the season, Arsenal outperformed their xG by +9.3, indicating better luck or better finishing.

A big factor in this:

Trossard started twice as many games in the second half of the season (12 to 6). He upped his minutes from 666 to 983.

In the second half, he scored 9 goals on 4.1 xG.

Whatever precise concerns you may have at Trossard as a winger, there’s an important thing in this particular sport.

This extends elsewhere. Success rates of free kicks are especially low everywhere these days. But hey, the last time Arsenal scored on one of those was September 21.

Every team has off days. Bangers are a bailout technique of so many top sides.

More of that please.

Problem: Insufficient out-of-the-box threat

Solution: Get Rice, Saka, Ødegaard a few more shots from deep; acquire a midfielder/forward with high-level ball-striking

5. A few more big passes?

Speaking in a far-reaching (and lovely) interview with the Athletic, Rice had this to say.

“The manager doesn’t like diagonals, really. He does like diagonals if you’re going to gain an advantage from it.

“So if it’s there to hit and it gives you an advantage, you hit it, of course. But if it doesn’t, he’d rather you play short relationships, let them come onto you and play around them to then create the space for him (the winger).”

“We’re really big on playing ‘same side’.”

The idea of “same side” playing is hopefully some evidence that players playing tight 1-2s isn’t a bug, but a feature of the system. A list of the best short-passing sides has a lot of similarities to the best sides, period.

Xabi Alonso is perhaps the most notable traitor to his class. Leverkusen played 2,525 more short passes than anyone in the Bundesliga; meanwhile, they played 230 fewer long passes than anyone in the league as well.

That said, they do differ in one way. Leverkusen play twice as many switches as Arsenal.

Now, I’m not advocating for a huge uptick in this pass specifically (a switch is defined as traversing >40 yards laterally on the pitch). But I do think that some of the passes from side-to-side need to be a little bit more immediate, with fewer layovers on their flight.

What I’d like is a more of this kind of thing.

The big switches are still a powerful tool against mid-blocks, so long as they’re hit low, fast, and right — as Toni Kroos taught us time and time again.

Arsenal have scored on a lot of headers this year, but many of them came via set play. I’m a broken record, but I tend to think the whipped crosses to the far post can still see an uptick.

Havertz ended the season with 18 shots via header all year. I think that number can still rise.

In short, simply add a touch more KDB to our attack.

Problem: Short passing is a thing of beauty; nasty-boy passing can increase

Solution: Open up Rice (and a new DM), White, and Saliba to switch a little more (when there is an advantage); more back-post crosses; speed up the movements when transferring from right to left and vice versa

📝 Other notes

Here are some final, scattered stuff on my mind.

Don’t drop nine points to Fulham and Aston Villa. Sorry, I had to! Many of these points (left side solidity, speed, big passes) will help in those matchups.

Arsenal could score in the first 15 minutes a bit more. This is from understat:

In the first half, I could see fortunes improving. For example, here are the team’s respective records, as logged at halftime:

Man City were 21-10-7: 40 goals for, 16 goals against (1.92 PPG)

Arsenal were 18-16-4: 42 goals for, 12 goals against (1.84 PPG)

In other words: at half time, there was a 42% chance Arsenal were drawing level; it was actually more likely that Arsenal were drawing or losing than winning; the draw rate was only 26% for Man City. Arsenal were a little cagier, but this also helped them trail less, of course.

Arsenal made 18 errors leading to shots. I’m not too doomsday about this. This is a young team; when the other team attacks, it’s almost always a max-pressure situation. This also includes some of those GK spills we saw earlier in the year. Still, we’d like to see this number go down as the project progresses. (Declan Rice had zero, by the way.)

Something I’ve touched on here and there: I think Arsenal can sometimes rush and pin the ball up in the final third with too much haste. I’m not talking about counters here, but the normal build-up sequences. They should potentially keep the ball in the middle third with more patience so that they can pull around and move the block with a little more flexibility.

I’d talk about freeing up Saka to come inside, or Ødegaard floating laterally, or Saliba being more free to carry, but that all generally looked to be improving as the year went on. An improvement in left-side dynamics should get Ødegaard and Saka a few easier goals. As good as White/Saka have been, the Timber/Saka pairing looks pretty nasty as well.

In all, I think a focus of the transfer window has to be fewer trade-offs. Ultimately, at this level, you don’t want to choose between your progressive left-back or your defensive left-back. You’d like to start a progressive, defensive left-back.

A little more practical depth would of course be welcome. We can talk tactics and profiles all we want, but looking at the 2-0 defeat to Aston Villa, the truest conclusion felt intensely human: they were spent.

⏭ Next

I see my word counter is vibrating off the desk. I have even more to say, but will hold that for future installments. It’s a sickness.

From here, we’ll tackle the transfer market, and do some rankings of potential fits.

I’ll end with a rehash of the fuller Arteta quote:

"Don’t be satisfied. Because we want much more than that. And we’re going to get it."

Above all:

I’m intensely grateful for our time together.

I’m grateful for you.

Let’s keep it going, shall we?

❤️🔥🍖

![r/Gunners - [Billy Carpenter on X] And why do we like Trossard again? r/Gunners - [Billy Carpenter on X] And why do we like Trossard again?](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!jQPk!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F12a1f3c0-9bd5-49be-bfb0-30732a37fd18_886x958.jpeg)

Thank you a million times over Billy. In a season full of incredible moments, being able to enjoy your newsletter has absolutely been one of them. Your silly bullshit has made this season even better.

Great work this season, Billy. Love your writing and the care you put into understanding the game.