Frustrated after Fulham

Observations in the wake of a disappointing draw, including: the urge to scapegoat, whether Arteta is overthinking, how Havertz impacts dynamics, mistakes, set pieces, Vieira's explosion, and more

Society loves a scapegoat.

Look around, and you’ll see examples everywhere. The bully deflecting blame to the less-powerful kid. The politician telling you that your problems are caused by some extraneous group: it’s them, over there. The internet commentariat ringing the shame bell for the day’s Main Character, sometimes for good reason, sometimes indiscriminately, but always in haste.

This is nothing new; the phrase itself goes back to the days of Leviticus. The reason this is so embedded into our shared consciousness — or, rather, unconsciousness — is because there are powerful psychological factors in play. The simplest one is just that it’s easier to blame someone else than to look at ourselves. But it’s more than that.

Here’s how one psychoanalyst puts it:

Scapegoating not only feels cathartic but also stokes a sense of self-righteousness, a “seduction of virtue,” Stewart said. By casting others as bad or inferior, a person will “come up smelling like a rose,” she added. “That is a defence, too. We’re justifying. We’re moralising. The righteous mind is a dangerous thing.”

If society loves a scapegoat, the footballing world especially does.

There are understandable reasons for this. These fuzzy, unrestrained passions are why we’re here, and nobody should suggest that players, managers, or executives are immune to critique: they’re millionaires who signed a deed on a house in funkytown. And though most of these critiques are rooted in some truth, we also know that things can get, shall we say, disproportionate.

There is a reliable tidiness to the operations. Last year at Arsenal, it seemed some invisible baton — previously held by Granit Xhaka or Nuno Tavares or whoever comes to mind for you — was cleanly passed from Sambi, to Vieira, to Nketiah, to Holding, and so on. There may be many, but there must always be one.

I’d suggest there is another, more innocent, factor in play: the very human desire for straightforward explanations in a sport that often deprives us of them. Hundreds of millions play worldwide; the best athletes on Earth go through thousands of hours of training, competing and moving and climbing the ranks until the best ones are funneled into a few select squads; they perform in jam-packed stadiums over a hundred or so minutes, having thousands of tiny opportunities to prove their superiority. And yet, entire games, trophies, and careers are regularly decided because of one slip, one bouncing ball, one referee protecting his mate from stress. Everything is hostage to random strokes of bullshit, luck, or variance. Football, as always, is a metaphor for life.

Even when the performance is to blame, the reality is complex. Any number of factors can contribute: a small but cascading tactical issue, a learning curve, a beloved player making a mistake, a phasing-in period, a wet pitch, a genuine recurring problem, an opportunity missed by a blade of grass, a simple bad day, our own expectations.

It can feel bewildering to navigate all that. It’s much easier to yell HEY MAGUIRE, YOU’RE FUCKING SHIT!!!

We are all subject to these forces, and I guess all we can do is try to be aware of it when apportioning blame. Part of the objective of this little writing project is to dive into that complexity with full force and see what we can learn.

Reflecting on a day in which Fábio Vieira, a previous sacrifice, put in one of the more impactful substitute performances you’ll see, and Kai Havertz, the current target of ire, was passed the invisible baton, let’s do just that.

📘 Is Arteta thinking or overthinking?

It’s tempting to describe this as Arteta’s experimentation phase; I’ve seen more than one reference to him going “Pep galaxy-brain” of late.

First, I’m not sure that’s the insult it’s intended to be: “Oh, LeBron is just going through his Jordan phase.” Pep is the best to do it, and while there have definitely been examples of his overthinking causing issues, it’s also impossible to decouple his experimentation from his success.

But secondly, after the preseason, I’m not sure how galaxy-brain these opening games have actually been, aside from a genuinely new look against the back-five of Forest.

There are new players phasing into a complicated system, with nascent relationships being forged.

Otherwise, some points must be considered first:

The team’s two top choices at inverted full-back, Zinchenko and Timber, have been injured.

Without them, there are three obvious choices available:

Scrap inversion, playing a double-pivot of Rice and Partey, which has many benefits against top sides, but may generate insufficient attacking threat against lower blocks

Invert from the left with remaining players, most likely with Kiwior as a midfielder, as we saw against FC Nürnberg

Invert Partey, playing last year’s system, but with flipped dynamics

This is to say: I’m not sure this was the most experimental version of what Arteta could have done on Saturday. In fact, it may have been the least disruptive.

This was a 4-3-3 base, with an inverted full-back, a hybrid CB/FB, and five attackers pinned to the front-line. The similarities outnumber the differences by a vast margin.

But new players and flipped dynamics are an adjustment all the same. This was visible in the first minute.

🤬 Another mistake. But why?

We’d like to avert our eyes, but let us watch and rewatch to understand what happened. Here’s a repeating gif of the shameful moment in question:

From the opening whistle, Arsenal were looking to do some fluid rotations with Partey and Rice. The system is based on corresponding movements like these. But here, there was a set of cascading issues:

After Partey had dropped to the backline, White carried toward the middle, essentially regaining a position as a wide CB

Partey, seeing this, and noticing Rice moving outside, interpreted this as a trigger to join and support the midfield, doing so in White’s periphery

White either didn’t see this, or ignored it, and cut back out wide as an expressive full-back, even though he had no cover

No one is home

Saka delivered an expertly-weighted through-ball to Pereira

In short: Partey can join the midfield here, or White can act like a wide right-back, but not both at the same time.

There is no coherent structure in the above screenshot. Seeing as how White cut inside, Partey responded within his purview, but White still went back wide — then Saka passed to nobody in particular, there’s some blame to go around. (And none of it, sadly, falls on Havertz.)

But there is also a tactical update which deserves support and critique. Playing as a CB, White has clearly been given the green light to pick his spots to roam forward. When enough coverage exists, he’s looped around for overlaps, providing another unexpected attacking threat. This is a new weapon against the block, and is the equivalent of Gabriel doing this last year:

It’s a good wrinkle — so long as it’s actually covered. In theory, Rice should offer much more of a platform for such things.

At 34’, White could see that Saka was isolated 1v1 after a switch, and knew Partey, Rice, and Saliba could all rotate centrally by the time Saka did his work — so he committed forward again, unafraid and looking for a goal:

In the second half, you could see White going forward out wide — so Partey peeled backwards to cover any counter:

…and when White was ultimately dispossessed near the edge of the box, Partey is back to clean up the transition the other way.

It’s even White who eventually retrieves the ball:

With all of Arsenal’s struggles at home in the opening minutes, though, I question the player instruction early. Even without hindsight, it would have made sense to tell White and his colleagues to lean steady in the first 15-20 minutes or so, and then layer in some of these more dynamic, highly dependent, riskier rotations after things settle in.

🐐 How Havertz is impacting dynamics

The plan for Havertz is multi-faceted, says Arteta:

“We can play different formations and shapes. And we can move structures in different ways that in the past we haven’t been able to do. I don’t want Kai Havertz to stick in one position. I prefer to do that with other players as well because when you do that you are more unpredictable, you open your options, you open their minds to other things. When you explore that, and we have many examples of that in the squad, you get very good surprises.”

Playing Havertz in this spot is essentially a transaction: by reinforcing the backline with build-up players, you “free up” one midfielder from many of those responsibilities, and allow him to default as a bonus forward.

Another, entirely oversimplified, only marginally-true way of looking at The Havertz Transaction is this: if this position is 10 yards further from build-up, he can be 10 yards closer to goal.

Looking at Havertz’ lanky frame in a position that is nominally called “midfielder,” one can naturally wonder if a more controller-type should be played here. Against the best sides, I myself have worried in these articles if Rice’s bully-8 role is properly fortified. But there has been a consistent philosophical through-line in recent Arsenal transfer windows, as more prototypical 8’s are passed up for 6’s and 10’s.

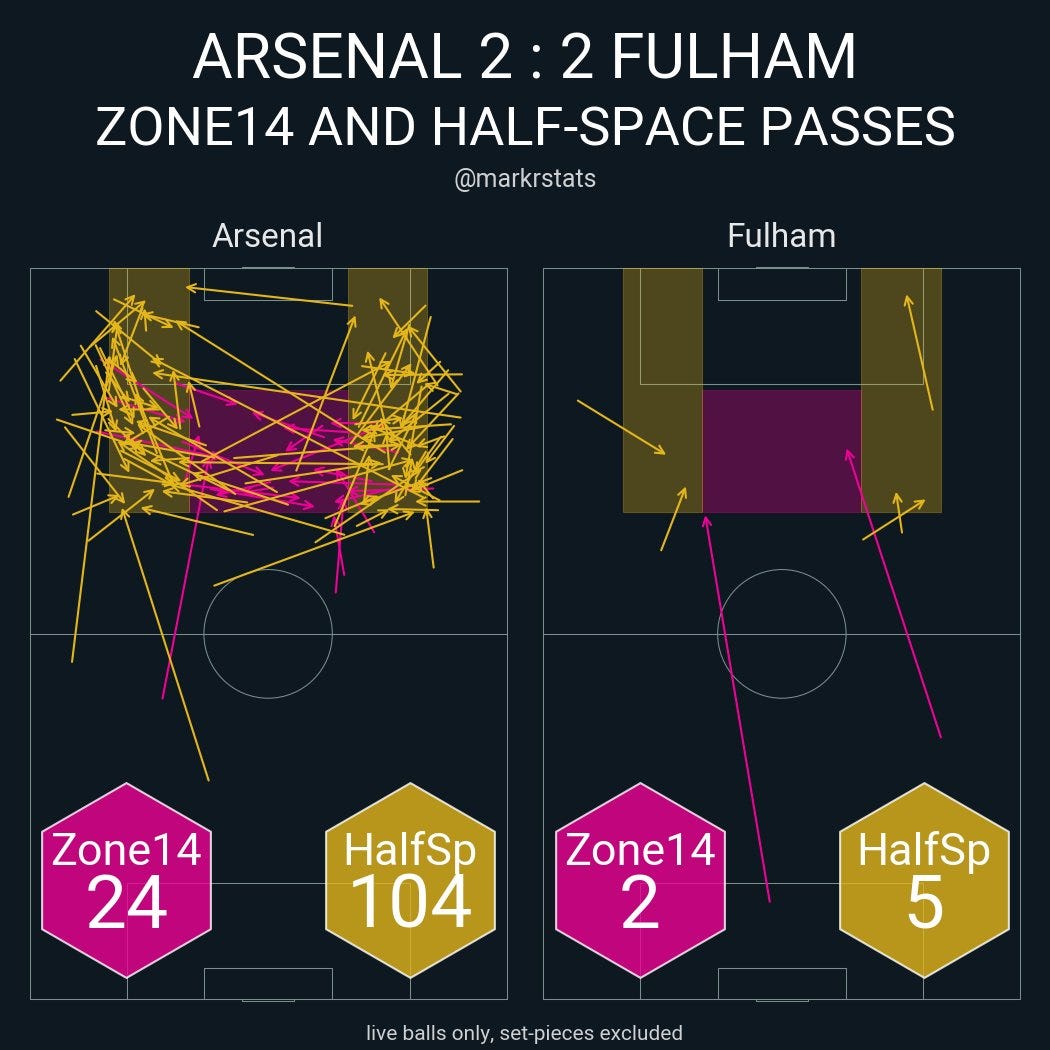

Here, the first thing we must interrogate is how these dynamics may have impacted the team’s ability to get the ball forward toward the goal.

Does this look like a team with endemic structural issues moving the ball forward?

What about this?

Or this?

Nah. On a day when the possession differential is so stark, and the field tilt is 90.4%, it’s hard to argue that more midfield control was the problem.

In fact, there were some truly beautiful switches of play. The plan of attack was to overload certain areas before quickly changing play and immediately generating threat. This was largely successful in manufacturing chances against a compact, four-man block.

In one early example, White switched to a wide Trossard, who then ping-ponged it to Saka at the back-post, who cut it back to Havertz — who got his leg kicked as he went for it, sending it wide:

These White/Rice (get it?) switches were incredible throughout.

And that last clip helps you see what Arteta looks to receive in the Havertz Transaction: hopefully, an increased presence at the mouth of the goal. It’s easy to picture a Xhaka hugging closer to the corner of the box, whereas Havertz, at his best, attacks the ball like a striker.

White’s exploits, and Kai’s almost-hits, were on further display with this over-the-topper. Again, this is something genuinely additive to this Arsenal side:

Havertz also had a flick-header that nearly created a goal off a set-piece. This takes a lot of height and skill, and causes the desired chaos in the box:

There was also a marginal-offside run that created Ødegaard chance that went into the back of the net. (Havertz does have a habit of running marginally offside, as Chelsea fans will tell you, so he maybe doesn’t deserve too much credit there.)

For 20 or so minutes in the first half, amidst Trossard’s struggles to declare his presence, Havertz was perhaps Arsenal’s most threatening presence. There were still glimmers of the other side: a lack of assertiveness in his decisive actions.

While many saved their loudest groans for Havertz in the second half, here’s where he got ‘ole Billy’s rankles up the most:

His actions are fairly understandable — he was asking for a popped ball for him to head into the net — but he still needs to attack this opportunity with full force. He’s done the run, he’s slipped coverage, he’s completed all the hard stuff — now he just needs to do the final bit and tap it in. (This is also worth zero xG by the way, if you’re looking for an example of the shortcomings of a shot-based stat).

Regardless of his position, those are the moments which will make or break his Arsenal career. It’s why he was signed.

There is also no doubt that he has to turn, burst, and carry with more aggression.

But to recap: he was fairly excellent for a 10-minute stretch, he was passing-grade for the longest stretch, he was shitty for a 10-minute stretch. On the day, the same could be said for Saliba, Ødegaard, Saka, Martinelli, and others, and some of their mistakes were more costly.

I’m patient. Especially in this role, against a team like Fulham, the team has now proven it can advance the ball, dominate possession, and generate chances. If he merely taps that one in — as he did against Barcelona — or Martinelli hits on that flick header, or a couple other bounces go his way, he would have done his job.

He is not above criticism. He is not above rotation, even in key games. He is, however, above much of the online shit flying his way.

💥 What Vieira offers

At half, Arteta acted early to try and reset the dynamics, first subbing in Nketiah for Trossard, then bringing on Vieira and Zinchenko in the 56th minute.

Vieira’s actions looked confident and bursty immediately.

Arsenal drew level on — you guessed it — a switch. Rice evaded some pressure, and pinged it out to Martinelli, who controlled it effortlessly. Vieira sprinted out to perform the “Xhaka cut” beneath his buddy:

Interestingly, you’ll see that Kiwior had pushed forward from the CB position to be a second striker, occupying Fulham’s CBs and acting like a screener in basketball. After the initial free-kick phases, he could be seen doing this late in the game when searching for a goal, as well.

Saka buried the penalty, of course, and only two minutes later, Vieira spun this one into Saka. Look at the late whip over Issa Diop’s head. This is fucking ridiculous:

That’s the play that caused Bassey to go down. Twenty seconds later, Vieira ripped this one into Nketiah to make the score 2-1:

Vieira also delivered the forward pass to Nketiah who drew the second yellow on Bassey, which should have proven decisive, and drilled this scissor as well:

It was a comp-reel performance, the one we’ve all been waiting for, and hopefully, the establishment of a new baseline.

“Vieira needs to bulk up” turned into a bit of a meme last year. It was my preferred, sardonic way of reacting to unrelated, disappointing moments in the season. Oh, one of our stars biffed a pass, leading to an early opposition goal? Vieira needs to bulk up.

Of course it carried a kernel of truth, as the Premier League is certainly a physical adjustment. But what you’ll see throughout his actions on Saturday is that absolutely none of them relied upon improved physicality; what the fluid attacker really needed was to improve his processing speed to make his actions more immediate. The Premier League can be cruel to those who hesitate. Anybody is capable of getting pushed off the ball if they hold it for a beat too long.

Build in a half-second of thinking into that initial underlap, and he doesn’t draw the penalty. He showed everything else last year, but the margins are slim. Small improvements can lead to huge results.

Vieira, like Havertz, also requires some mutual adjustment. Despite his frame and his technical aesthetics, back in November, before Havertz was ever linked, we noted Vieira’s sneaky-raumdeuter qualities, comparing some of his off-ball runs in Portugal to the ungovernable Müller. The burden of adjustment has not been on him alone — his teammates have to find his oddball associative runs with more frequency.

Adjustment can take a little time. I’d build in a clever way of bringing this back to Havertz, but you get the idea.

🗡️ The set piece dagger

Which brings us to the final, throw-your-TV-remote moment.

The second Fulham goal has many fathers. The first is a fairly worrying, and altogether annoying, tendency to dial down the intensity once a lead is gained.

Especially after the reinforcements have arrived, this team has the depth and technical prowess to win through 300,000 passes, but can settle into a sleepy version of Moyesball. They are still disciplined enough not to concede from their normal block shape, but any mistake or set piece can spell trouble:

Zinchenko was incredible once he came on, and his relentless line-busting passing is a big reason for the second-half charge. But for his second straight substitute appearance, he alternated some brilliantly controlled passing with moments of needless risk. You may have remembered his attempt to dribble around Palace from the left-wing position while down a man. As an elder statesman on a young team, he should be careful to lead by example in these close-out moments.

But there’s another recurring issue: squad composition on corners. Arsenal have a core — Ødegaard, Saka, Zinchenko, Martinelli among them — who are exploitable in these situations. This makes the makeup of the remaining players so important. Last year, I went back to watch all the corner concessions, and noticed how many of them were when this Big Guy “ratio” was off, and the opponent could too-easily isolate onto the smaller players.

With Gabriel not playing, Jesus (who is an asset on these) not in yet, and Havertz/Partey out, the balance was tipped the other way. A lineup of Zinchenko, Jorginho, Vieira, Saka, Nketiah, and Martinelli is just too thin, and if corners are one of the two ways Arsenal concedes, it’s something that Arteta can be more conscious of.

Or, I’m overthinking it. While most of the squad looked a touch lethargic, this was another one where Saka should have simply done better. It’s a rough one to watch back:

Bah.

🔥 Final thoughts

After a thoroughly disappointing outcome, it is annoying for geeks like me to try and reassure people based on stats, underlying tactical considerations, and other Very Logical Reasons. We shouldn’t seek to win the “second-most passes completed in the league” trophy, and ultimately shouldn’t rush to ascribe too-familiar mistakes to the fundamental unfairness of football. In fact: if you fuck up twice, and get punished for it both times, that sounds pretty fair to me.

So the analysis is simple. Continue to build upon tactical and technical superiority, fuck up less, and score more. Whether you find that analysis satisfying and/or encouraging is up to you.

It’s natural to be impatient for the next step. The helpful context may be that Arsenal still boast the third-youngest team in any of Europe’s top-five leagues this season:

As a result, the burden of leadership can fall upon a contingent of younger players, who largely perform with a wiseness beyond their years. The power of their example in work-rate, pressing quality, tactical know-how, and technical aptitude reverberates throughout the pitch. They are why Arsenal are so good, so soon.

But they are, after all, still young. Zinchenko, for example, is the fifth-oldest player on Arsenal’s new squad list. Three of the four players ahead of him are newer additions: Raya, Trossard, and Jorginho. The left-back would be the 13th-oldest player on Man City.

This group can continue to improve their example in a few areas by cutting out early mistakes, being more relentless and assertive in the final action, not letting energy dip after a lead is acquired, and improving their effort and leverage on defensive set pieces. Arteta still has a few things to iron out, too.

Some final notes:

Scapegoats don’t only come in human form: they can be tactics, too. If it wasn’t clear above, I am far from throwing in the towel on inverting with Partey as one of the many options available to this Arsenal squad, though I prefer the more familiar, Zinchenko variety. By and large, the team has been able to progress and dominate the ball against this level of opponent, creating chances along the way. Rice’s ability to lean on either side is starting to pay dividends in the defensive coverage. That is not to say the dynamics are perfect, or that this is currently a preferred option in the Champions League or anything. As it stands, Martinelli isn’t receiving enough support — he’s being asked to perform Saka’s 1v1 heroics from last year, but without an overlapper. Saka and Martinelli are more comfortable with the standard dynamics at the moment. But on a calmer rewatch, paired with the statistical underpinning, the quick switches and triangles generally paid ample dividends. Trossard didn’t have the best individual performance but his work to push Havertz and Martinelli inside looked promising. A personal inclination? If things start to feel stagnant up front, have players flip: Havertz can perform some overlaps for Saka, and Ødegaard can try and deliver balls for Martinelli to run to. I’d generally lean against this as a default formation (their finishing quality is higher in the current spots) but the potential is there.

I am so heartened by Kiwior’s performance. He barely put a foot wrong all game, and in fact, was one of the steadier performers on the day. His physical characteristics are so apparent, but he did some subtle coverage and rotations that showed an increasing comfort and boldness in his game. He can still provide more support up top, but as a way of reintroducing himself in a meaningful contest, this was nice, nice, nice.

I can still cling to some tactical reasons for Gabriel missing this one (the inversion was from the right for most of the game, Kiwior was performing well, and subs had to be preserved), but it’s feeling a bit more tenuous.

It’s worth noting that Havertz has still never played in the “left-8” role with Zinchenko behind. When that side started to come alive, there’s context: perhaps not so much “Havertz off” as “Zinchenko on.” The dynamic naturally shifted once a true inverter was pushing up there in support.

This was also the debut of Rice and Zinchenko as a double-pivot pairing. While it was natural to wonder how they’d interface together, as they’ve historically occupied the same zones, Rice is looking comfortable just about everywhere at the moment. Early returns are so good.

I would have written a lot more about Rice if I didn’t already do my full gush-piece last week. He has no business getting up to speed quite this quickly. His peak is stratospheric.

Still, there are some little gaps in anticipation between the likes of he and Saliba that led to chances the other way. Do you have 98% certainty that will get ironed out soon? I do.

Nketiah reminds us of the importance of game-state on player perception. While it was commonly believed that he struggles to make an impact as a sub, he was usually brought on in the less-intense moments when Arsenal were protecting a lead and Arteta was channeling a bit of his inner Moyes. When a goal is needed, he often provides it. He also seems to be continuing his development trajectory, showing little new details to his game every week. What a guy.

Whatever I’ve said here, I am open to rotating basically everyone on the squad. I’ll weigh what I think is best against United, but going back to a 4-2-4 with a Rice/Thomas double pivot and Havertz or Jesus up top makes some sense in my book.

After Forest, I wrote about how it was a delightfully player-dominated affair, with individual moments of brilliance making all the difference. The opposite can also be true. While the structure led to regular chance creation, the finishes were often missed or overly tame. Combine that with a couple huge mistakes, and you have your answer.

Again, whether you find that explanation dispiriting, encouraging, or satisfying is up to you.

Happy grilling everyone.

May Havertz turn the haters into donkeys.

🔥

*me, reading the BBQ after tweeting obscene things about Arsenal drawing a single Premier League game*: ah yes finally some common sense

Idea for next bbq; havertz is a luxury fellaini and that's a good thing.

Have a theory lots of people see havertz as some kind of Ødegaard/ozil/bergkamp type technician.

I think actually he's technically average not comparable to those types of players. But he's physically elite and what he will provide is this.

If you look at fellaini's best years he's scoring .5 G/90 which is outstanding while not showing any kind of technical ability really.

He profiles quite similarly to havertz statistically too.