Havertz?

Where he works best, why he has underwhelmed for Chelsea, and how he might fit in for Arsenal

Earlier this week, in another dimension, we used the quizzical links to Timothy Castagne as an excuse to talk about squad-building. Specifically, we discussed the need to remove single points of failure from the team by creating redundancies across the pitch.

The term we borrowed (and likely misused) from the world of mission-critical engineering is “triple modular redundancy.” Triple, as in three options. Modular, as in different configurations. And redundancy, as in backup processes in the event of failure. Do that, and your bridge generally won’t collapse.

I like Castagne fine, and was all good with him as a ~£10m versatile “load balancer” in the event of the ultra-pricey midfield double-swoop, ending the piece thusly:

He wouldn’t be my choice, but […] I understand the logic. I can live with almost any ancillary signing if Caicedo and Rice are on the way. If it’s just one, I’d look to level up.

Lord knows we’ve had plenty of updates since then. As I hit publish, the Rice talks keep progressing, and Arsenal has reportedly taken themselves out of the running for Caicedo.

Now, I’ve been beating the drum of the “Twin 10” configuration for a while now, but adjusted my expectations for the potentially ridiculous market opportunity a Caicedo/Rice could present. I believe both of them have sneaky-high potential in advanced areas if supported correctly, and think their versatility (and Caicedo’s ability to invert) means you can still have the option to slot an attacking 10 with them. It’s a best-of-all-worlds situation.

But once the numbers started looking like £100m+ all-in for Rice, and started moving from the £70+10 originally floated around Caicedo to a cool Tony Bloom ask of £120 million (which I doubt he’ll get), the realism and resignation started creeping in. That’s just too much dough.

Considering the moves so far, is it any surprise, then, that we were promptly linked with an attacker with so much “flexibility” that nobody knows where to play him?

Enter King Kai

During the Champions League winning run of 2021-22 — in which he scored the winning goal against Manchester City by beating Zinchenko behind — a nickname started gaining steam: King Kai.

Havertz himself said it was a media creation. Since then, the player self-reported a new nickname:

“Some of my teammates call me Donkey.” A grin creeps across Kai Havertz’s face. “It’s not because of my football,” the Chelsea forward adds, as if he needed to. Instead, he says, it is something deeper. “From day one, I felt a special relationship with donkeys. It’s a very calm animal: maybe I personalised myself in them because I’m calm too. They chill all day, don’t do much, just want to live their life. I loved them always. And when I lost, I would go to the sanctuary. You look at the animals, see something human in them. It was a kind of recovery, a place I felt peace.”

“King Kai” and “Donkey” may be a good way to describe the two sets of reactions to the news that Arsenal was interested in signing Havertz.

I’m of the camp that loves his fascination with donkeys, without a hint of irony. In fact, I’ll go a step further. Those who would mock a man’s friendship with a donkey are no friend of mine.

In general, I think it’s better to share and discuss possible biases rather than pretending they’re not there. Temperamentally, I find myself rushing to defend the merits of players when I feel like the discussion around their game has been unfairly flattened and stripped of context, particularly when they’re being held to the standard of a transfer fee they didn’t pocket. Sometimes, I can find myself hanging on too long.

That is to say: I like Kai Havertz, was immediately excited by the links, and it took me a moment to remember that the thought may not be widely-shared.

I fully understand any trepidation. Those with concerns are slapping down the sunshine-pumpers like Billy Beane in that scene from Moneyball:

Scout: "I like Geronimo. The guy's an athlete. Big, fast, talented. Clean cut. Good face. Good jaw."

Billy Beane: "But can he hit?"

Scout: “He’s got a beautiful swing. The ball explodes off his bat. He throws the club head at the ball and when he connects he drives it.”

Billy Beane: “If he’s a good hitter, why doesn’t he hit good?”

Advantage, Brad Pitt. At most things in life.

Baseball, of course, is situated around a more controlled, individual showdown: pitcher throw ball, batter hit ball. Football is a lot more bewildering. The swimmy interactions of 22 players inform the actions of every other player on the pitch. Managers despotically hover over thousands of little factors, then relinquish near-complete control when the game starts, shouting at people who can’t hear them while the result is determined by individual moments of brilliance, a surly fraternity of Mancunians wearing fluro-yellow and needlessly long socks, and huge spikes in luck and variance. But I repeat myself.

There are countless examples of players being misprofiled and ill-served by their circumstances before discovering new “form” elsewhere. One little example that creeps in my mind is Benfica’s midfielder Florentino Luís, who moved from a trainwreck of a situation at Getafe to a side led by the brilliant Roger Schmidt:

Last year at Getafe, he completed 18.3 short passes per 90 at 81.6%

This year at Benfica, he completed 38.5 short passes per 90 at 94.2%

Are we led to believe that he suddenly discovered how to complete a short pass?

Nah. Situations matter. But situations are complex.

Comparing Havertz

I could use saltier language, but no situation is quite as “complex” as that of Chelsea, where managers are seasonal workers, ballyhooed players get dressed in the hallway, and attackers go to die. But we can’t write off everything we see, and should interrogate further.

To begin, I created a list of 66 hybrid attackers across the world — i.e., those who could play in multiple roles across the front-line. I then created a quick algorithm based on advanced defending, dribbling, carrying, and key passing — but heavily weighted it towards actual goal creation. Then, with some extra weights for age, Sofascore variables, FotMob rating, and Transfermarkt value, the objective was to find the best value-based production among hybrid attackers last year.

I didn’t have time to get the methodology a little more buttoned-up, but wanted to share a little window of progress in response to this story.

The top 10 was filled with names you may expect:

Dybala averaged .93 G+A per 90 in the games he played; that means he broke the system. Güler’s underlying stats are fucking bananas, even when league-adjusted, and his value is still listed at £15m (which may actually be around his real transfer fee). Foden being here despite a £110m transfermarkt value is pretty wild, as well.

Not too far behind were the likes of Kudus (who would be higher, but some of his advanced passing stuff is almost non-existent), Eze, Brandt, Kubo, Sané, and Trossard.

Where does Havertz rank based on his performances this year? With a season spent as a lonely striker for a side that didn’t score, few opportunities to key-pass, and an £80m transfermarkt value, he's down in 46th — alongside the likes of similarly-disappointing Mount and Jota, plus less-developed attackers like Reyna and Lindstrøm. A lot of overall stats are still plenty good, but with the model weighted towards actual goals, assists, shooting efficiency, etc, his production didn’t compensate for that value.

Needless to say, Arteta wouldn’t be interested in Havertz if he thought 2022-23 was the height of Havertz’ potential. So, as a thought experiment, I kept his transfermarkt super-high and then plugged in his Leverkusen stats to see where he fell:

That would be more like it.

But it’s no guarantee that he could return to such levels, or, rather, consistently display them in the Premier League. With that, we stay interrogating. Let’s roll into some of the more interesting questions of his game.

Why Kai?

Let’s start with the bull case.

👉 Space manipulation

In nearly every game, even the unproductive ones, you can see his brilliance as a Raumdeuter — and understand why Real Madrid was at least a little interested in him as their Benzema successor.

He can be the first in the box and pick out tap-ins, but that’s not where he’s best. He is in the absolute highest tier when arriving as the second or third runner, with the objective of manipulating defenders and peeling out a pocket of space to exploit.

Here’s an example.

Against Iceland, Kimmich gathers the ball and blasts a through-ball behind to Sané. Havertz is somewhat close to Gnabry in the middle, and right away, Havertz sneaks behind his man:

As the play progresses, Havertz sees that both CB’s are likely to run with Gnabry, so he lays up his run to preserve a pocket of space in front of him:

Now that they’re both sprinting, he settles into a pocket, against the momentum of the runners. Sané cuts it back:

And it’s an easy goal:

That’s not the fiercest competition, but it lays out a clear formula: (1) Attacker ahead. (2) Recognition of exploitable space. (3) Goal.

Let’s see him pick on somebody his own size.

These are the runs of play where I like him most, and illustrate why he can be such a dangerous back-and-forth tournament weapon.

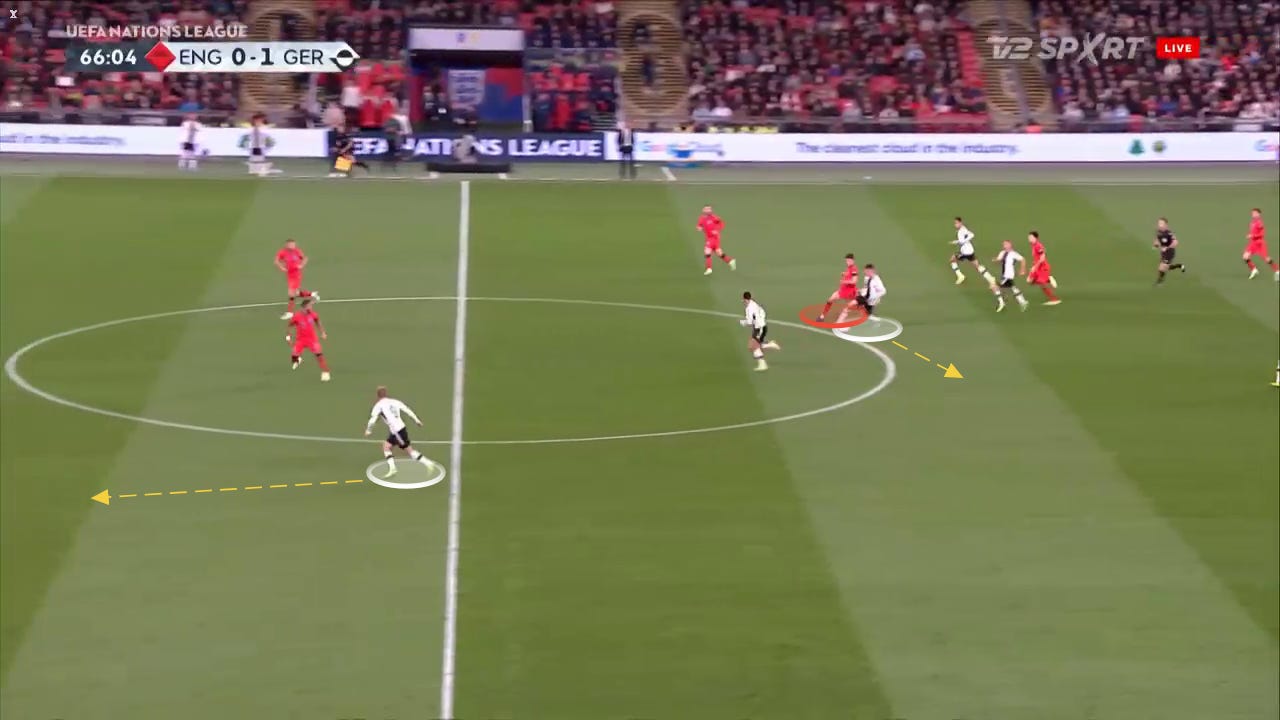

Havertz gathers the ball in a transition opportunity, and Rice starts leaning in to him. (Side note, one of the only things Rice should work on defensively is that he should foul more, IMO.) Rather than tangle with the beast, Havertz pulls away:

He then hits to the … wait for it … attacker ahead, Timo Werner:

And as Werner holds play up while reinforcements arrive and England sprints back to get set, Havertz peels a run through the middle and then angles it to the right, behind the blindspots of the defenders. He ultimately scores from this space:

Again: Attacker ahead. Recognition of exploitable space. Goal.

👉 Immediate acceleration

And that’s a crucial thing in Havertz’s column: real speed. This ability to sprint and modulate on a dime allows him to try out different angles until he eventually finds the best real estate. While he may be associated with savvy box movements like his compatriot Müller, sometimes a defender does match his idea — and Havertz simply turns or outruns them.

Here, during his best run of form with Chelsea (during the 3-4-2-1 Tuchel Champions League blitz, where he was a “Twin 10”), the ball is played long to Mount. Havertz sneaks in from the left and looks to read the situation:

As Mount gathers it, Havertz turns the defender’s hips, before sprinting behind him. Goal:

In all, you may think, at first glance, that Havertz generates most of his opportunities by cutting in from the half-spaces (primarily the right). But in actuality, so much of his production simply comes by these box movements through the middle — settling into small, open pastures and just straightforwardly kicking it in:

In that chart, you’ll notice something else: 26 aerial goals.

👉 Aerial duels

With a 193cm frame, Havertz is #4 amongst all non-defenders in the Premier League in winning aerial duels. He has the highest win rate of that group:

Tomáš Souček, 114 (55.3% win rate)

Ivan Toney, 109 (48.2%)

Aleksandar Mitrović, 100 (48.8%)

Kai Havertz, 79 (57.2%)

This, almost understandably, helps push managers in the direction of playing him at advanced striker, where his quick, tall, muscular bursts can occasionally look Osimhenian.

In the Champions League last year, Jorginho hits a clipped pass over the back — and Havertz outmuscles Carvajal to get to it, heading it past Courtois:

It should be said, by the way, that I saw a wonderful connection between Jorginho and Havertz while going through this tape. Their (literal) lockers were next to one another, and with Jorginho seemingly fully bought into the project, he may be able to provide a helpful character reference for Donkey King Kai.

Meanwhile, the lack of this threat in the frontline was one of the few frustrating bits of Arsenal’s season. Of all those who played in the front-five — Saka, Ødegaard, Jesus, Nketiah, Xhaka, Trossard, Martinelli, Reiss, Vieira, ESR — only a couple show any proclivity to look for headers, and even then, only sporadically.

On a dangerous whipped cross like this, all three of Trossard, Xhaka and Jesus let it ride — perhaps expecting somebody else to go for it:

This aerial presence would be much-welcomed. While the size and height of individual players can be overstated — go watch Bernardo Silva dribble through the Champions League if you think slight players can’t be successful — I think the team makeup of size and strength may be underindexed. On corners, Arsenal typically got into trouble when there were too many slight characters in the box, which helped opponents isolate and create mismatches. The additions of Havertz and Rice would go a long way.

👉 Key passing

When playing in central areas throughout his career, Havertz is 75% at passing into the penalty area — a number that always needs context, but is still a good starting point.

On the right is how Arteta looks at the pitch:

Control of “Zone 14” is typically described as the most important battle, akin to controlling the middle of the board in a chess game. In a positional system, the pitch is usually split up into 20 zones, to instead stress the importance of the half-spaces. This, indeed, is where Arsenal originates most of its attacks.

Havertz also likes these areas, but may also add a new dimension when it comes to passing from the central area on top of the box.

In this video that has made the rounds, you’ll see a compilation of such passes while at Leverkusen. We should always take compilations with a grain of salt — they are a motivated creation, and generally don’t show an indicative swath of a player’s skills — but I think what’s notable here is the sheer volume of sick passes in this clip:

Playing in the furthest role up can squander this potential. To help illustrate, look how accurate his penalty area deliveries are in the last year — but look how relatively rare it is:

This is because he is often already in the box.

👉 Other stuff

As we’ve seen already, Havertz excels at link-up play. The GOAT sang his praises on this front:

"I thought he was good on the first goal you could see held the ball ever so well," Henry told CBS Sports. "He reminds me sometimes, a little, of Robin back to goal the way he can hold the ball. Robin van Persie was very good with his left foot, the touch was always immaculate he tried to bring people along. This is why out of the guys that used to be wingers or No.10 he plays as a nine because with his his back to goal he can hold the ball well. Now he needs to make sure he can transform that into more goals because you can play off him.”

Despite the lack of good, forward runners ahead, Havertz still showed excellent underlying numbers on this front. Look at his medium pass completion percentage below, where he is excellent at weighting the ball:

Despite Chelsea playing a confusingly lethargic yet high-possession style, Havertz still availed himself pretty well when it comes to counterattack contributions:

Finally, I’ll mention his pressing and work-rate. This used to be more of an uncertain quality about him, but particularly this year, effort was never the problem. I have incomplete data, but knew he led the team in distance covered against Dortmund. In fact, unless I’m missing something, I didn’t find a single Champions League forward who covered more ground than him per 90. It goes a long way to showing why manager after manager stuck with him while trying to clean up culture with their jobs on the line.

In spite of Chelsea’s almost-pressing ways for much of the year, his defensive counting metrics are high — and get sky-high when they are adjusted for possession:

He can still be a little leggy and lungy with direct challenges, but by and large, should be a plus on the press.

Finally, I’ll throw this in there: I think he’s got more ball-striking prowess than he’s shown.

OK, enough of this fuckin’ positivity.

Why not Kai?

OK, he sounds perfect. What gives?

👉 Bouts of slop

A player is inextricable from their situation, but is still responsible for themselves. An optimist would say that for all the attackers who have struggled at Chelsea of late, he may look the most regularly hard-working and competent. A pessimist would say that’s a low fucking bar, and we can come up with a lot of fancy ways of deflecting, but 6.3 goals per year for an expensive forward is, in football terms, bad. A realist can hold both thoughts in their heads at the same time and retain the ability to function.

I don’t like speculating on player psychology, but in this situation, there seems to a difference in the speed of his decision-making at Leverkusen and Chelsea. This is no doubt partially due to the increase in speed and physicality in the Premier League, but I’m not sure it explains it all. He has Premier League speed and size.

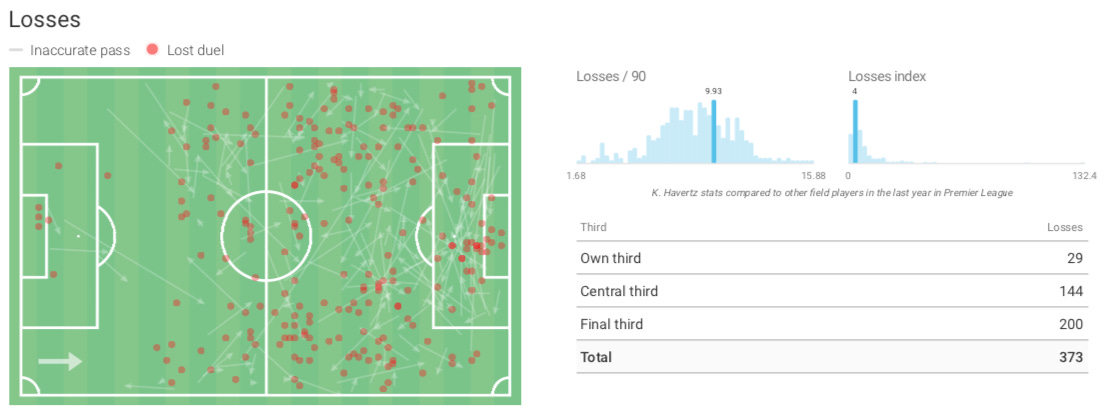

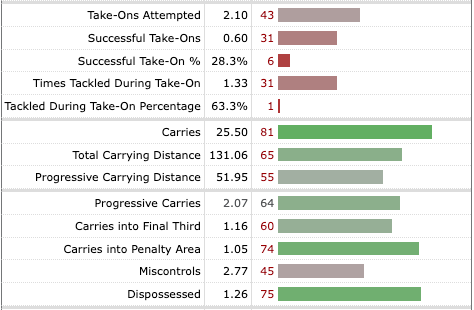

He has seemed prone to overthinking while waiting for ever-rotating cast of runners to appear, and can sporadically, and randomly, fail to show his technical gifts. This leads to three straight years of relative xG underperformance, and a relatively high number of losses — one that could be lived with if it resulted in more G+A production:

As he continues to receive the ball further and further in the box, and is more often getting the ball at his feet in more static situations, his take-on stats have been dropping every year. This year, as a more advanced striker, he’s been tackled 63.3% of the time. Yuck:

Which brings us to the next point.

👉 As a typical striker, he can get man-marked out in the box

When playing the most advanced role, he is the first to enter the box — and is thus man-marked by a CB, who these days is roughly as tall and fast as him. This takes away perhaps his single greatest asset as a player: the ability to enter the penalty area a little later, successfully lose himself in the process, and find a crease to operate and create a goal. With a single player following him around, the confusion is gone, and his sword is sheathed.

👉 As a winger, his wide 1v1 abilities are still unclear

He excels at rotations and interplay, and has probably had the most success in that regard in wide triangles on the rightmost edge of the box. But if he were to fill in for Saka at right-wing, could he supply a reasonable dose of the 1v1 production that keeps defenders hooked and gives teammates space? I’m not all that bullish, and have some of the take-on stats to prove it.

👉 Confusing physicality

You may have seen him be an outright bully, as his aerial stats show. You may have seen him fall like a feather. There is more in the former category these days, but they both still happen to confusing degrees.

If I had to explain it through mindless conjecture, I’d say this: his body isn’t naturally in fight mode. When he is expecting contact, he runs people over. When he’s not, he goes flying.

👉 Mid-block concerns

I went back and watched all of his duels in some of the early games at Chelsea where he was deployed as a low-8 alongside Kanté and Mount — including matchups against Wolves, Leeds, and Sevilla. It, uh, looked like a young guy straight from the Bundesliga: instead of holding passing lanes in deeper areas, he treated everything like a high-press situation — lunging, tackling, missing, and opening up gaps.

These were different times; two Lampards eras ago, to be precise. If he were to play the left-8 at Arsenal, he’d flow down to the middle of the 4-4-2 block alongside the DM. As we’ve covered at length, the “Xhaka role” as it was previously defined wasn’t especially interventionist. I’m generally confident in his ability to do this with proper coaching. He has the size, strength, speed, and positional sense to excel. But this opinion isn’t especially corroborated by the Premier League tape thus far.

👉 Right foot

A lot of his imprecise finishes are the product of a right foot that can let him down.

👉 He’s expensive, his wages are high, and there are other concerns

Thank you, Captain Obvious.

Where should he play if he joins Arsenal?

There is a red, flashing sign blinking over the remaining discussion: Arsenal are seemingly willing to pay a healthy transfer fee and wages for Havertz — starter’s wages, some would say. There is one clear opening for a player like him. It is in Xhaka’s spot in the lineup.

But we are here to discuss, so discuss we shall.

To start, I found some interesting subtext to 2022 praise of ESR by Arteta:

“I think he can play in four positions. As a left winger, a left attacking midfielder, a right attacking midfielder and he can play as a nine, very, very well.”

Notice anything? He didn’t say “left-8” and “right-8,” like we are wont to do. He said “left attacking midfielder” and “right attacking midfielder.”

Moreover, when discussing Xhaka’s role evolution with Jamie Carragher, Arteta said this:

"I think it was a necessity. The squad wanted to evolve to another level and be more dominant and have more resources in the final third to attack and to score more goals. We needed to make that change.”

I covered this all in great detail in this piece: Xhaka, ESR, and the future of the left-sided 8.

Which brings us back to Havertz. I think this marvelous video — a couple years old now, but still ringing true — is probably the best place to understand his optimal usage:

In it, Alex Stewart had this to say:

“There are two different reasons that a manager moves players around. Sometimes that’s because there are gaps that have appeared in the squad, and there are players of sufficient quality to be able to plug those as and when is required. Somebody like Havertz is more where you want to put him where you can most exploit wherever the opposition is weakest. He’s not a gap filler. He’s a person who you want to play at the 8 if you want those surging runs from central midfield. He’ll play at 9 if you want to pull defenders forwards and exploit spaces behind.”

Ultimately, my belief, as it is with nearly ever player we discuss these days, is that it’s not about nailing down one specific role, and more about creating triple, modular redundancy across the pitch, and regularly exploiting the player’s best skills, wherever that is.

Those skills are such:

Savvy and bursty space manipulation in the box

Key passing in and around the box

Playing in attacker(s) ahead

Aerial dueling

High-pressing

The findings from Chelsea, especially this year, aren’t too complicated. Here’s the easiest way to visualize it, with two relevant games I watched — one where he was meh, and one where he looked every bit the star that Chelsea hoped for:

That shows him leaning to the right, still as the “striker,” but with players ahead and runners around. While he’s leaned right for a lot of his career, I think he can be just as effective (although in different ways) floating through the left — where his crossing radius is a little better and he’s scored more goals, I think.

This is to say — saying he can’t play striker (or any other advanced role) is a little reductive, as the role can be interpreted any number of ways. He just shouldn’t be the most advanced player.

Next, I pulled his career data across prospective roles, in every competition:

With all that in tow, here are some build-up shapes which might suit Havertz best. You can assume that every form reverts to a 4-4-2 midblock out-of-possession, and a rotating 2-3-5 in more advanced areas:

1: If I were drawing up the best way to get the most out of Havertz, it would be this: as the point of a 3-diamond-3, with license to roam forward, across, and behind. By inverting Thomas from the right, Rice can step a little forward and do what he does best — and Havertz can be covered behind by both Rice and Gabriel. There are some things to sort out in terms of block shape (does everybody in the backline shift over a spot?). Also, there is thin depth at midfield-inverted RB, where only Partey (and perhaps White) can play at the moment. It would be great to fortify that before the window is closed.

2: This is pretty much the 22-23 build-up shape, with Havertz in for Jesus (who can rotate across the wings), and Rice in the left-8. Havertz should be highly-used in link-up play, with runners (principally Martinelli) running forward into central areas. This quasi-striker role suits Martinelli well, and Havertz playing behind him and arriving late will suit his abilities nicely. He’d just need to be careful to not get trapped in a specific zone in the opponent box for too long without rotating out.

3: The most straightforward way to incorporate Havertz into the side, and probably the most likely outcome. There are a lot of reasons to believe that Havertz can do a lot of what Xhaka did, just at a higher level, and that the defensive load is not as cumbersome as it may seem. That said, that left Havertz/Zinchenko still flank feels a little vulnerable in advanced possession.

4: Against top sides or excellent presses, the team can revert to a 4-2-4 double-pivot, with a rotating striker pairing up front. This would be incredibly sturdy defensively, and is how Manchester City ultimately bested us.

From there, he can rotate as Saka and Odegaard cover as needed (though I’d marginally prefer Havertz to play centrally and Jesus play wide when Saka gets a rest).

These four shapes would also be a good use of Rice: a good dose of 8, a good dose of 6, and always central and part of the action.

Triple. Modular. Redundancy. Babbyyyyyy.

“Oh no, did this fuckin’ guy just suggest Havertz as a rotation option at striker?”

🔥 In conclusion

I am bullish about the potential of Havertz in this team. I am not very bright, so my perspective is fittingly simple: get high-effort, high-talent, young players, and the rest usually follows.

But I am also quite price-conscious here. There is too much unevenness, too many unknowns, and too much leverage to go to a £70m range with this.

Now do I actually think it’s an enormous risk? Not necessarily. In a world where Matheus Cunha fetches £44m, a 24-year-old Havertz can just duplicate his disappointing 22-23 form and still provide about £50m of value. And as long as he doesn’t preclude other reinforcements (I was so heartened by the Roméo Lavia links), anywhere in that £55-60 range strikes me as A-OK. The counterarguments should be priced in, but the upside is enormous. Like: fucking enormous.

I’d been working on my Big Board of targets (which ranks players based on age, value, potential, underlying stats, etc), and recently added Havertz. In the £55m range, he would be my second choice of the hybrid attackers, behind Szoboszlai. Once that number gets towards the £70+ range, he falls off the map, behind the likes of Wirtz, Simons, Kulusevski, Mount, Güler, Kudus, Maddison, and Gonçalves.

In other words: I think it’s good news however turns out, so long as Arsenal doesn’t actually pay the unreasonable fee.

I’m sure we’ll have updates and non-updates galore in the hours ahead.

For now, I nap.

Happy grilling everybody. 🔥

Great piece, and I love that arrested development meme!

I would love to see him come to Arsenal as he’s one of the most technically gifted players with speed and acceleration that I’ve seen and he’s more than willing to put in the defensive work. But, the price does concern me in terms of wages (and in terms of transfer fee if it gets to 60M+). That said, I have to think that if Arsenal have already ironed out personal terms, his wages will be coming down considerably from his time at Chelsea.

Superb piece Billy. One thing that I worry with Havertz in the team is that Rice's strengths may be under-utilized (especially if Rice is deployed at the bottom of a diamond). I was honestly hoping that Rice performs the role that Xhaka performed, until the Havertz links messed up my calculus. That said, I do agree with you- there is a player in there, and a damn good one. There are a few people who can fix him, and Mikel is one of those.