How it's going

What we learned against Sevilla and Sheffield United, looking at the ESR/Havertz pairing, interesting tidbits on progression and chance creation, Freestyle Tomiyasu, what unlocks Nketiah, and more

The fixtures come well and fast these days. It can feel hard to keep up, but we’ll do our best.

Recent newsletters have begun with pleas to respect the opponent. For all their hand-crafted travails, Chelsea have a dangerous squad, one that was a tougher challenge than their spot in the table would suggest; they’re well-suited to face Arsenal. Lens, too, offered an enormously difficult atmosphere and some worrying underlying metrics. Any cup game against Sevilla in Spain (particularly on a two-day recovery) should be treated with the utmost seriousness.

In the spirit of intellectual honesty, then, I must say this: Sheffield United are bad. The powers-that-be took a truly fun Championship side and did everything in their power to ensure Blades fans would be as morose as possible upon league reentry. They sold off Iliman Ndiaye to Marseille, Sander Berge to direct relegation rivals Burnley, and lacked a compelling vision (or budget) for restocking these departures, though a few interesting talents snuck their way in. Take that, and add a nine-man injury list by my count, and things are looking bleak. As somebody who enjoyed watching them last year, it makes me a bit sad.

The results have been predictable: bottom of the league, bottom in goal differential, and bottom in a lot of other stuff. You know how Luton Town have looked particularly feeble this year? Sheffield United have given up 43 more shots than them.

From Arsenal’s perspective, a 5-0 home destruction of the bottom-dwellers had the knock-on effect of fortifying our statistical CV. Just like that, Arsenal have more goals than Manchester City and are joint-first in goal differential, whatever concerns there have been about an early adjustment period. This should serve as a handy reminder of how much fixture strength and sequencing can impact our impressions.

So the opponent helped the squad look back at their best. But there are a bunch of other factors in play. To better understand those, we have to take a quick look back at the games that preceded it.

We’ll be focusing heavily on the midfield.

👉 Residual lessons from Chelsea

There were many emotional reasons to like Arsenal’s performance in the second half against Chelsea. Once Declan Rice — and his teammate for a brief moment, Robert Sánchez — gave the team the slightest hint of a point, they grasped a draw with both hands. Encouragingly, they left disappointed.

“I really liked going into the dressing room and it’s really quiet, after drawing 2-2 with Chelsea and coming back from 2-0 down,” said Arteta.

As such, the review of the game tape was probably extensive, and there were a couple of key areas of improvement in the wake of a somewhat understandable, but quite frustrating, result.

For one, Mauricio Pochettino did a handy job of decoupling Jorginho and Declan Rice, making the older guy defend in space:

…and for another, Chelsea absolutely jam-packed the middle, making central access difficult to find (in a running theme on the year). Ødegaard had trouble directly impacting the game.

Indeed, Ødegaard has been a bit less impactful in attack than last year, a situation for which Arteta helped add clarity: “Martin has been carrying a little thing that wasn’t very comfortable in the games … I think he has endured a lot.”

Ah. This was a friendly nudge that we rarely have the full story, and should pontificate accordingly. But if you’ve found yourself wondering if the captain offers a sufficient threat to the attack, consider this: one look through the tape shows that the opposition managers clearly do. Bissouma was glued on him, for example:

But other things are true as well, and they impacted the two games to follow.

👉 Notes on progression and threat

A lot of interesting things are afoot with Arsenal in regards to progression and chance creation, and it feels like a weekly discussion in this newsletter. Part of the intrigue is that it feels a little hazy to parse. So let’s keep parsing.

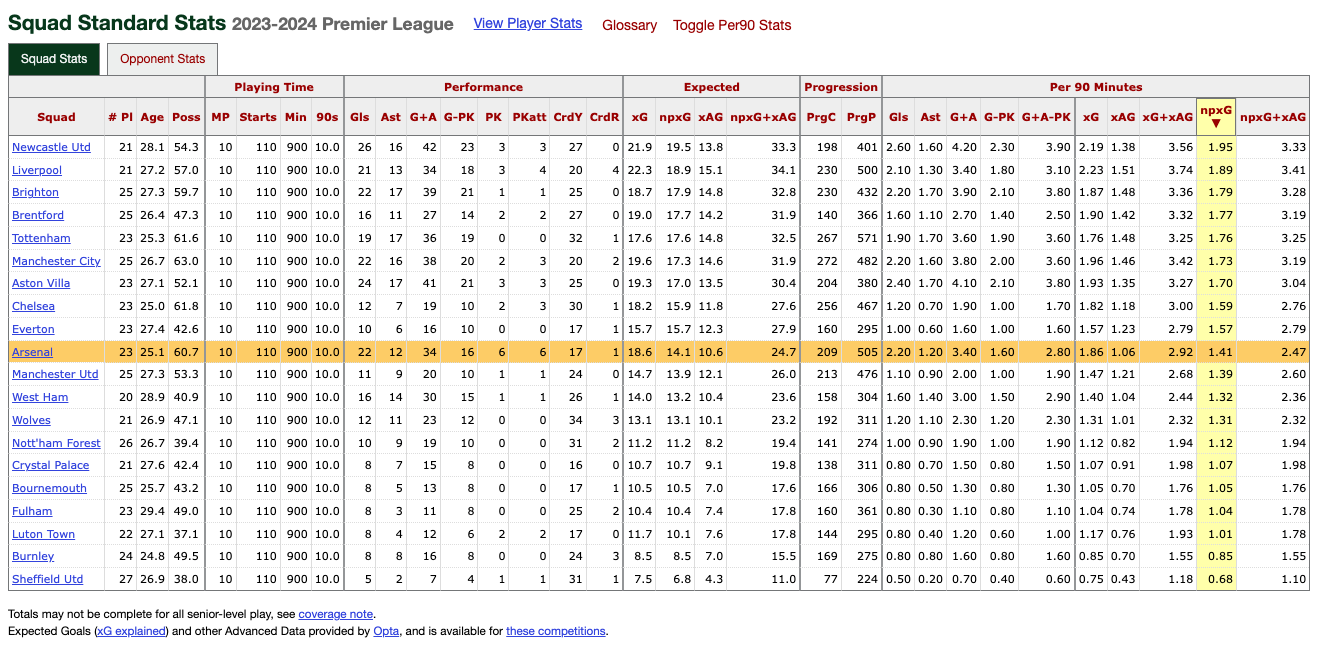

By now, you probably know the following: Arsenal chance creation is down. The simplest way of illustrating this is just that non-penalty expected goals are at 1.41/90, or 10th in the league, below Everton. Not as fun, not as good:

Relatedly, Arteta also made a bold (and risky) decision to sacrifice some typical midfield solidity through the signing of Kai Havertz, who has not been able to match Xhaka’s progressive passing output. While he’s been a difference-maker in pivotal contests, he hasn’t personally piled in the goals that would offer the clearest compensation.

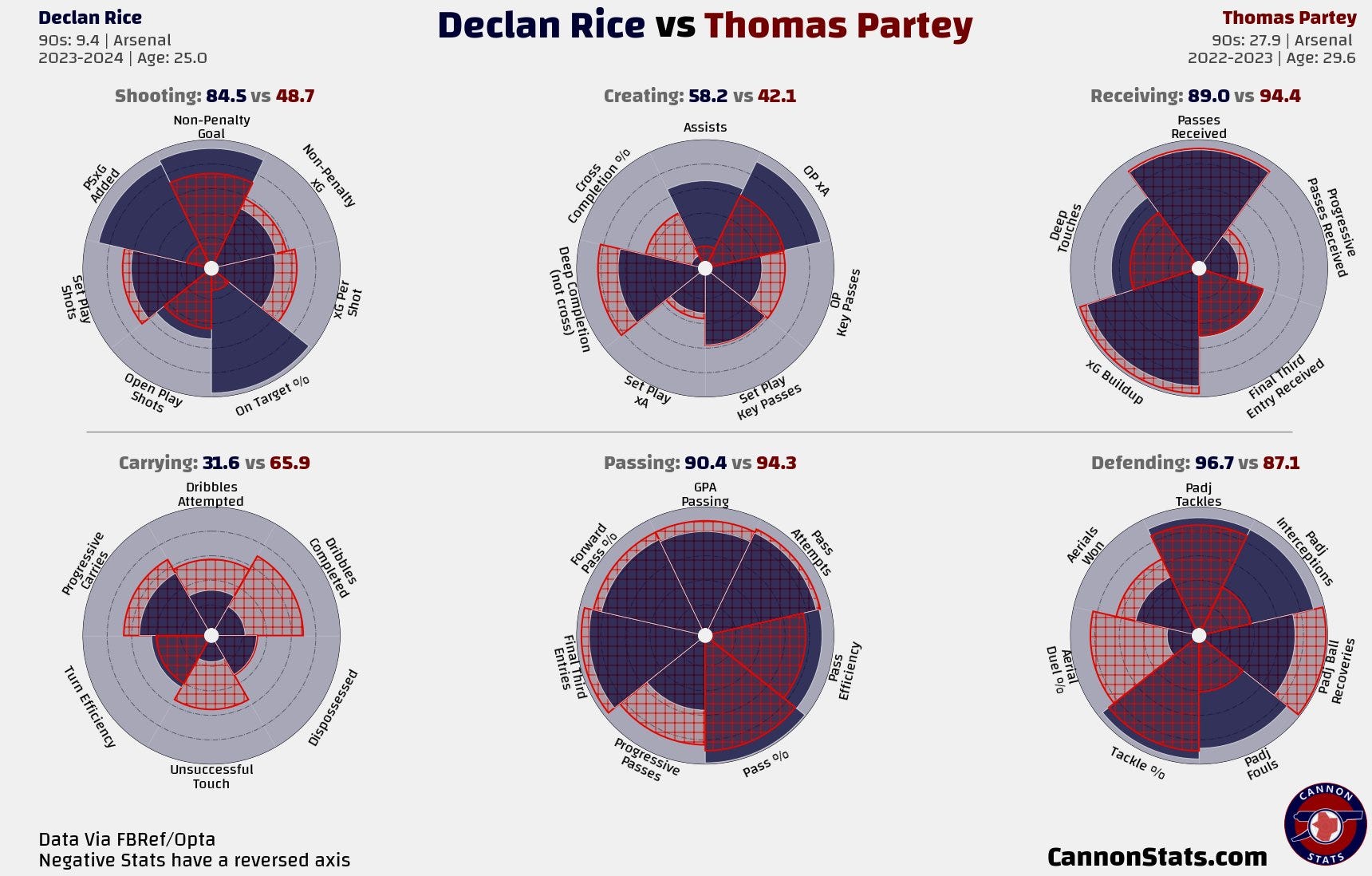

From there, questions turn to the difference between Declan Rice and Thomas Partey, and whether or not Ødegaard is simply struggling to be at his best.

For the Rice/Partey question, we can again lean on the great work of Scott Willis at CannonStats (follow, subscribe, etc):

There, you’ll see Rice performing admirably, particularly when you consider that he played some of these games in the more off-ball #8 role. It seems unmistakably true that Partey added a bit more directness and immediate ambition through the middle last year, and to date, outperformed Rice as a dribbler.

But some of that may be due to overall schematics rather than individual performance. I’d suggest there are some other factors to consider.

For one, progression isn’t broken — or even really struggling at all. It’s just happening in a different place. With an average opponent defensive line height of 38.14m, Arsenal faces the most stationary bus in the league, which is the equivalent of playing the deepest block (Nottingham Forest) every week — even though that average includes games against Man City, Tottenham, and the like.

Arsenal have more possession and, crucially, more progression with Havertz and Rice in the lineup. They also have no problem moving it up — and, in fact, have more touches in the final third than last year.

But if Havertz, Rice, Ødegaard aren’t contributing as much, how is that possible?

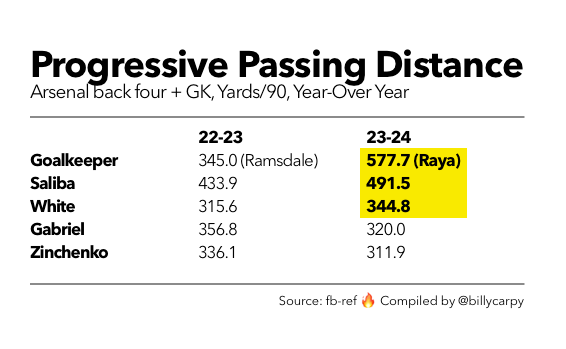

With teams sitting back, general progression is easier, and more readily taken on by deeper players — including (it’s all coming together now!) that new keeper of ours.

To recap: less aggressive pressing structures are being faced. More solidity is desired. And so progression is happening further back and with a more rightward lean, which has usually been true, whether Saka is in the lineup or not.

Considering those variables, then it makes sense that the “safer” Saliba/White side may be the chosen avenue to move things forward:

Meanwhile, the Raya/Ramsdale difference is pretty stark. As you’ll see below, Raya is offering 232.7 more yards of progression per 90:

If you’re wondering how there can be such a big jump in such a short period of time, we’re getting better glimpses with every game. I warned you about those drop-kicks.

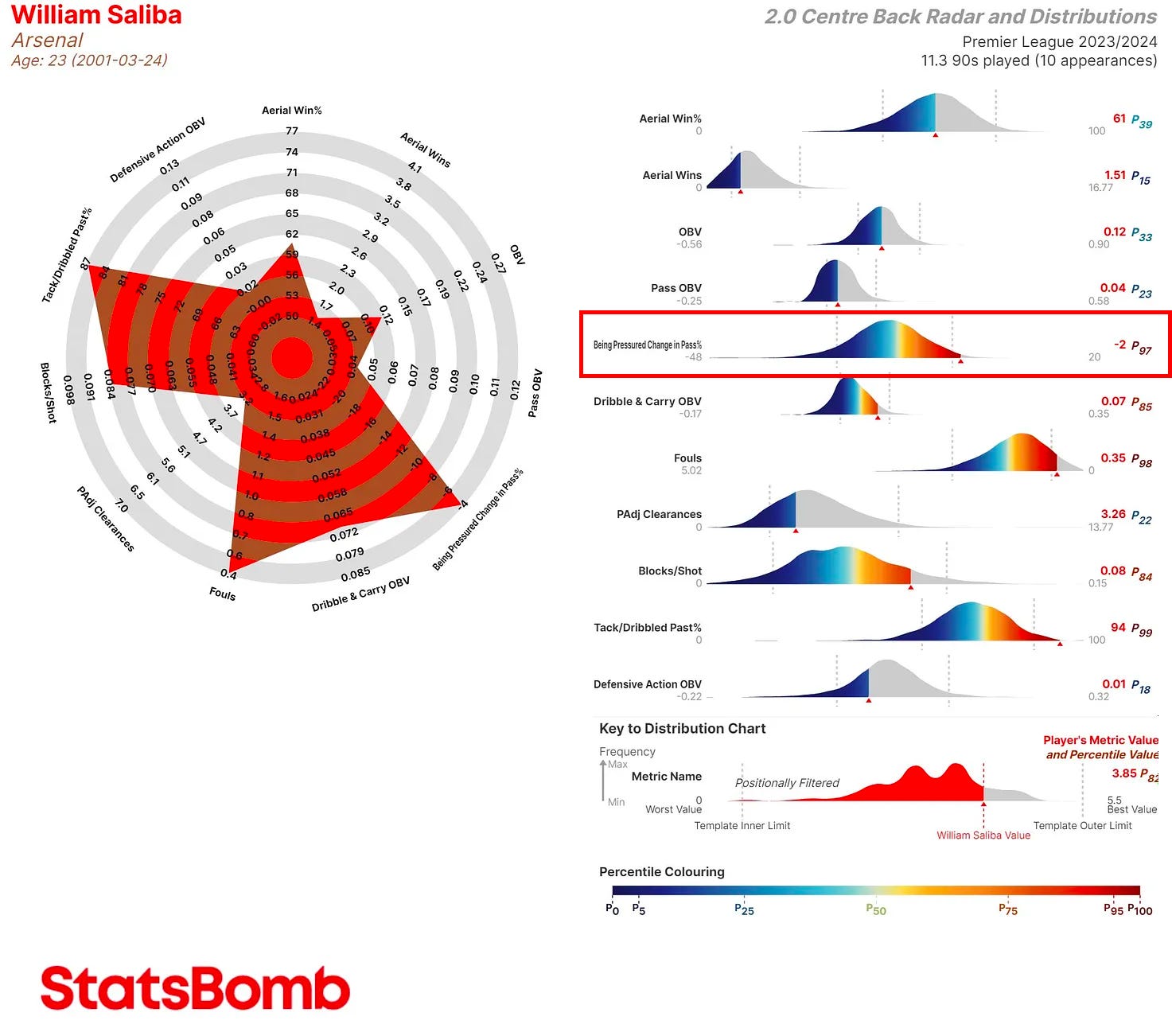

Which brings us to the genius alien in back. Saliba’s pass percentage changes only two fucking points when under pressure, making him one of the more press-resistant defenders in the entire world.

Yeah, I’m good with him having more of the ball:

It can be difficult to find interesting ways to talk about Saliba — “yeah, he was perfect again, no notes” — and perhaps this leads to some little details being missed. He’s passing 17 more times per 90 than last year, all at higher percentages (94% to be exact), and this — along with Raya — is offsetting much of what you see dipping in progression elsewhere.

So the problem isn’t general poss-ession, or prog-ression, or even getting the ball up to the final third. It is a little more straightforward than that: getting the ball from advanced areas into the box, and then shooting it from there. Goal-creating actions from live passes are down from 3.18 to 1.9 per 90.

Again, there are some different factors in play here. The first is that a priority of control means fewer bouncing balls, for both good and ill. In an Arsenal game last year, there would be an average of 100 loose ball recoveries by both teams. Now it’s 92. Even with a similar pressing output, that’s eight fewer opportunities for some happy mayhem to exploit.

Arsenal were skilled at pouncing right after winning a recovery last year, wherever it was. Remember the first minute against Liverpool?

But there have, strategically, been fewer of these moments this year — due at least in part to a desire to avoid situations like the second half of the return leg at Anfield.

Ødegaard helps demonstrate some of these changes. Despite approbations, he’s actually (#actually) now shooting a little less, and he’s receiving more progressive passes than last year.

So what gives? In line with what we’ve mentioned, the location of his touches has changed. While he’s touching the ball once more per 90 in both the defensive third and the attacking third, he’s having five fewer touches in the middle third. His touches in the box are also down a touch. He’s more likely to be doing simple passes in build-up, or crowded, wide passes in the right pocket, where things can get a touch static.

Looking through the tape, you don’t necessarily get the impression of a team that is trying and failing to push it through the middle. They are more likely to regroup and then progress out to the wings. Here’s a hypothesis for that: playing it out on the wings can still be dangerous for Arsenal, but is much less likely to result in a dangerous opposition counter than if you lose it through the middle, as Havertz did against Manchester United, or others did a few times in key moments last year.

Regardless, Ødegaard — and Arsenal more widely — are finding it a little tougher to get the ball into the box. What can be done about that? Arteta has been spitballing some ideas.

👉 Free Tomiyasu

I remember Tom Green doing a Norm Macdonald joke that went something like this: “I read a story that a 17-year-old kid stole a plane, crashed it, and survived. Why don't we just make the whole plane out of that kid?”

Seeing Tomiyasu jump up to be a second striker in the left half-space against Man City, and directly help win the game, a thought may have occurred to you: why don’t we just make the whole game out of that moment?

Arteta may be on the same page after seeing another great cameo against Chelsea. Immediately against Sevilla, Tomiyasu went up to the spot usually held by the left-8. Within four minutes, he was raising his hand on a Benjamin White free-kick. Look where he is.

Look at me, look at me, I’m the striker now:

This type of expressionism was to be the rule, not the exception. Within 15 minutes, he had dynamic rotations on the left, a nice shot on goal, and a bunch of other roaming plays that dripped with confidence.

When swinging out the expected full-back spot in build-up, he played a wanded ball to Jesus that could have very easily resulted in a goal.

But a lot of times, he was hanging out up here, which often evolved into nice little interplay with Martinelli and Rice.

Arteta has hammered home the importance of revealing cohesive relationships on the pitch, and Tomiyasu has looked wonderfully comfortable (and aggressive) in that half-space with Martinelli and Rice. What a nice surprise.

Like Timber bombing forward in his short stint before injury, there are other things to gain from this tweak. It has to do with Rice and Jorginho.

Here was what we wrote in the Rice scouting report, completed before he was signed, about how to update the role of “left #8” to increase Rice’s impact:

The question, then, turns to the “rest defending” — or how you get the most out of Rice defensively. As we’ve covered, if he were to merely inherit Xhaka’s role, he may not be optimally placed to cause the havoc he should.

The answer to that is pretty simple: more aggressive and automatic rotation with the left-most pivot, usually Zinchenko, from the first phase on up. With Zinchenko (or Caicedo??) coming over there, they can invade the box and pick out little tricky passes in crowded space, while Rice can hang back, keep the ball pinned, and survey passing opportunities:

Aside from the Caicedo wish-casting, this is what has happened. Remember how Chelsea were able to separate Jorginho from Rice, then force Jorginho to cover space? That’s more difficult if, upon a ball loss, Rice is already next to Jorginho, instead of standing up in the front line by default. Not only is he one of the pre-eminent counter-disruptors in the world (if not the very best), he has different responsibilities. The full-back has a responsibility to cover their flank — whereas Rice can cheat over towards Jorginho and offer as much help as needed. This helped provide stability against Sevilla.

Which brings us back to the other member of the midfield: Ødegaard. As we’ve covered, there is something to the impression that he may not have as much of a fluid relationship with the newer players in build-up. Rice wasn’t the #6 here, but regardless, another full game passed without him hitting Ødegaard with a single pass.

Boubakary Soumaré accompanied the captain all day, often shadow-marking him (i.e. standing in front of him) to stop the funnel of balls in his direction. When this happens, as it often does in this era, it can feel tempting to say Ødegaard just needs to play better. And if it’s just one player committing such coverage, that’s a somewhat fair expectation for a player on the Ballon d'Or list. But when a team’s primary motive out-of-possession is to stop Ødegaard, then it’s up to others to exploit the space he leaves behind. Because he’s always communicating and moving.

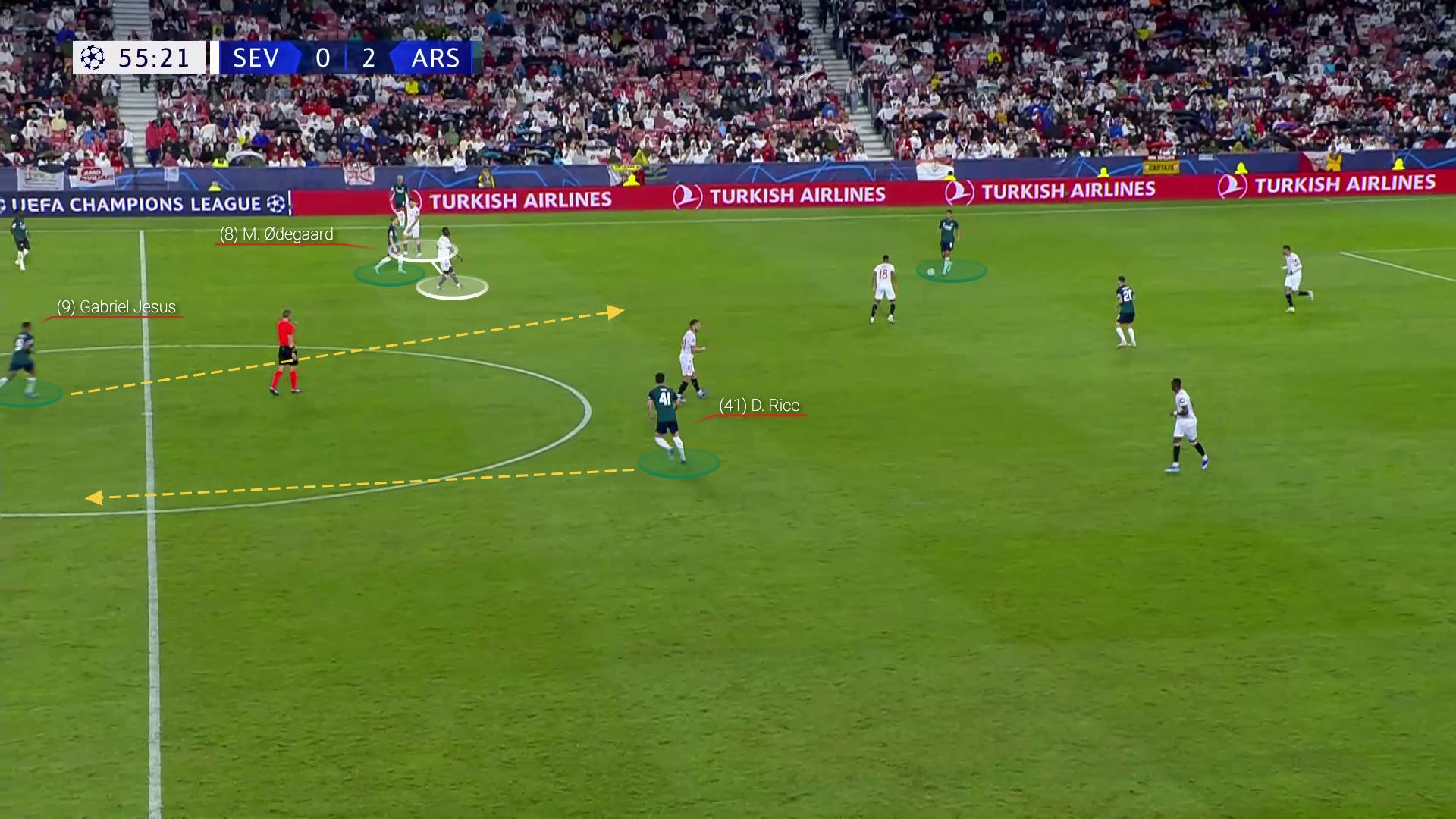

At 55’, there was a particularly good example of that.

As Saliba orchestrates play, Soumaré is again following Ødegaard around from the front, and his teammate is even helping. Three other smart players perk up and see how this can be exploited. As Ødegaard drifts up to drag Soumaré up the pitch, Jesus drops down into the space. This brings his CB along with him. Rice does a corresponding run into that space:

And in the following gif, you can see what happens next. Sevilla has to commit too many players to one side of the pitch. That means the other half is open, so as Rice drops back down, it’s clear sailing. He’s able to carry forward without obstruction.

These opportunistic rotations and corresponding movements are as much of a key as “Ødegaard just needs to play better,” which carries a bit of truth. By exploiting the opposition’s desire to cut off access in one place, you open it up in another. The rest of the game saw similar plays to Tomiyasu, Rice again, and all the way up to Jesus.

It’s just too many things to track for the opponent.

I’ll coda this section with a controversial take: please don’t forget that Ødegaard is really fucking good. Thank you.

👉 Rotations up front

The most interesting lineup decision on Saturday against Sheffield United was the “twin 10” attacking midfielders: Kai Havertz and ESR. I found myself wondering what I’d think if, even a year or two ago, you told me that the Arsenal midfield was Rice, Havertz, and Smith Rowe. Strange, fun times.

But with this Arsenal side, it’s very difficult to isolate the performance and tactical possibilities of any one player on their own. If my solution to everything seems to be “they need to get stuck into their spots less, play more expansively, and rotate more,” well, that goes a long way towards what I actually believe.

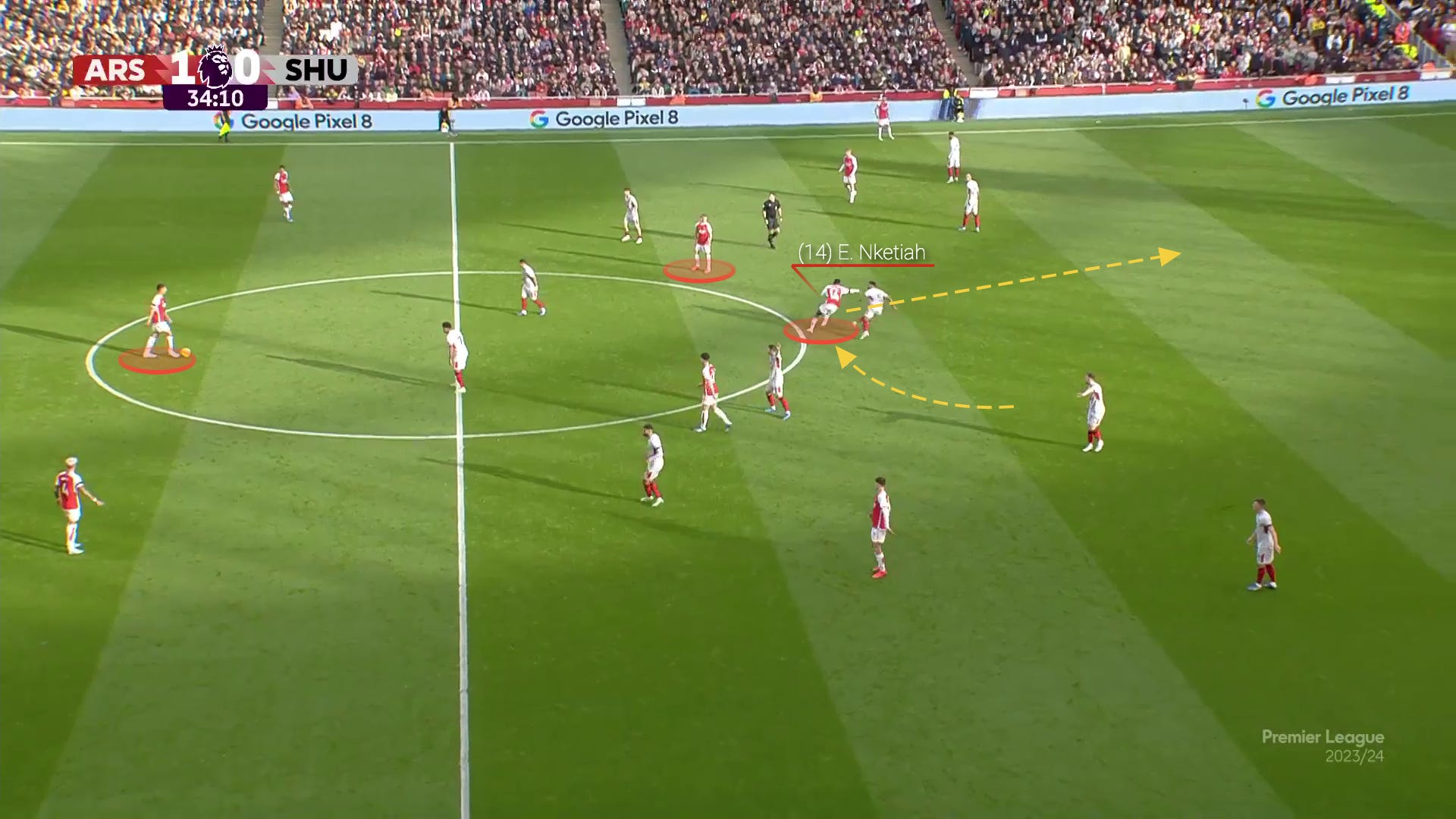

And this starts up front. My small brain sees certain correlations in the good Eddie Nketiah games and the more anonymous ones. The question is this: is he playing as the more connected, all-action striker he now is — or the more isolated, one-note poacher he once was?

The most extreme example of this was against Spurs. In 101 minutes, this was his one completed pass:

Against Man City, he again stayed stuck up front, and again had only one successful pass reception. He seemed glued to the shoulder of one big CB or another for the entirety of the proceedings.

If you contrast that with his better performances — and there have been plenty this year — and his impact seems to be heavily correlated with his level of involvement.

On the left, the meh stuff. On the right, the great stuff.

Watching the tape, it’s clear that the “park and poach” iterations of his role are part of the game-plan, and not just the product of a certain CB marking him out (after all, Ethan Pinnock on Brentford is a tough one). I think he does, temperamentally, like to situate himself near to the goal, but I hope we keep seeing the more expansive version of his game, as it’s felt throughout the pitch.

If you don’t have a physically dominant striker, and want flexible attackers at their best — and I’d include everyone from Saka, Havertz, Martinelli, ESR, Trossard, and Vieira in that mix — they need places to rotate into. Particularly if you start runners like ESR and Havertz, they need places to run into. And that can’t happen if the middle is always clogged with traffic.

Here, Kiwior shuttles it over to Saliba, and Nketiah drops into the lane a bit. Martinelli, at his freewheeling best, sees the opportunity and sprints through the middle. Havertz makes a corresponding run into the space:

…and it’s a 2v2 on the backline. The ball goes to a top aerial target in Havertz, with Martinelli running in the blind-side; these runs are so damn hard to track. It doesn’t fully happen, but is the product of all these corresponding movements.

For lack of a better term, this is Brentford Ball — which is a high compliment. There are a million examples of this throughout the years, but here’s the first one that comes to mind — Mee hitting it over to Toney for a blindside goal against Man City:

Think of the responsibilities laid at a CB’s doorstep there: track the ball, track the primary runner, track a potential shot, track a blindside runner, block that shot. It’s a recipe for the “good” chaos that has been missing in the box too much this year.

A little bit later, you’ll see Nketiah understand that this spot in the pitch is momentarily understaffed because he, Zinchenko, Rice, and Havertz are all there. He swings down to grab Trusty and usher him away from the area. You’ll notice Zinchenko seeing this in his scanning, because he’s always scanning:

…and now that area is wide open, and Saliba plays it to him at the exact right moment. This ends up with a near-chance for ESR.

Now, under a minute later, Nketiah is doing a similar thing — except, instead of curving the run around to prod the back-line, he’s dropping all the way back to Saliba. Zinchenko sees this too, and darts into the space, making a now-famous Arsenal left-back-striker run all the way to the box. Saliba hits him with a pass that nearly turns into a delicious chance.

If you’re Trusty, would you rather be facing the version of Nketiah that hangs on your shoulder all day — or does that, and drops deep, and curls his runs, and does channel stuff, and does false-9 stuff? All of this pressure is cumulative, and all contributes to the eventual goals, from my perspective.

ESR and Havertz were both solid. Crucially, starting them both didn’t contribute to a lack of control in a game like this. It’s a testament to the efforts of Havertz that dropping him into the defensive midfield spot of a 4-4-2 alongside Rice is a complete non-issue at this stage. Wherever you put him defensively, he’s been good. Arteta deserves credit for seeing this.

In a game with more than a few heart-warming moments, it sure was nice seeing ESR, Saka, and Martinelli combining on the left for chances. The constant rotations made all this possible. Look, ESR is a driving winger, Saka is an all-action attacker, and Martinelli is a shifty striker. All of your dormant dreams can be held, dear child, regardless of their original starting position:

Which brings us over to the right. As you’ll see below, I made a little grid to show how Havertz interprets the role differently to Ødegaard, and how that impacted Saka’s ability to move around some more, like we saw above:

And below, we can see that area in action. You’ll also notice an all-important concept in football: attracting commitments to take them out of the play. Here, White could have played a pass or two much earlier — but he first waits for Oliver Norwood to commit to Rice, and then won’t actually release the pass until Anis Ben Slimane commits a step forward. Havertz times his movement in lockstep, and Sheffield United has to scramble back to their block.

Now that the ball has progressed, Sheffield United does a good job of getting numbers back, but they’re not fully settled. Rice rifles in a half-space cross for a beautiful touch and goal from Nketiah.

…and whatever the opponent, some things were just nice to see, and would be great to see more of against all opponents.

This includes:

Half-space crosses: If teams are defending Arsenal differently, they must respond in kind, and update some of their mechanisms for goal-scoring. I’ll also speak about this every week, it seems, but KDB attempts somewhere in the vicinity of 5-6x the amount of crosses as Ødegaard. He’s better at it, sure, but there’s no reason that gap should be so large with Havertz and Martinelli (who is good at subtle de-mark-ations) in tow. As we saw with Saka-to-Trossard, or Rice-to-Nketiah, there are goals to be had.

Going long and coordinating runs: As we covered last week, Havertz makes aerial duels look way too easy for this to not be used as relentless advantage.

More aggressive, fluid rotations: I think Arsenal are hardest to defend when they’re moving over the place. They have few prototypical players at certain positions; almost everybody is a hybrid of some sort. That should always be treated as a strength instead of a hindrance, and unleashed accordingly. With that in mind, I’m not one to suggest the necessity of straight-up position changes for already-superstar players; it’s not an either/or proposition. For example, you can simply say “as a winger, we need to be more inventive in getting Saka into the half-space.” Or, “when things get stuck, the 8’s should switch, drop deep, and/or float more often.” I like what I’ve seen from White when he just parks as a right-winger, allowing Saka to push inward.

Despite not playing with a typical 8, Arsenal’s newfound depth nonetheless dominated the key areas of play:

Are Arsenal doing better than last year? Yes and no. They can undoubtedly become a more vibrant attacking side.

But one can take a simple view towards the objectives after last season:

Improve depth: Arsenal just won 5-0 in a Premier League game without playing Jesus, Partey, Ødegaard, Gabriel, Ramsdale, or the marquee defensive signing (Timber). Check.

Improve control, and keep variance minimal, against weaker sides: Underlying stats would seem to suggest that this has been the case. Some more goals would improve the margin of error.

Slay Goliath: Arsenal have beat Man City twice this year.

Looking at those three factors, not to mention a 0 in the league loss column, it’s hard for me to get too down on the performances so far. But the solidly mid-table goal and creation numbers should be treated as the issue that they are, and updates — perhaps even big ones — should continue to get pushed until the door unlocks. With Rice and Saliba in the spine, I’d reject the false choice of “control” and “creation.” I’d humbly suggest one option: playing Vieira and Trossard a bit more, because they make goals happen.

As I wrap this up, I just remembered that I never talked about someone I really wanted to: Jakub Kiwior. Oh well, I don’t have all that much interesting to say.

He made 98 actions on the day, and I went back and watched them all. Here is my constructive feedback: he overhit one pass. That’s all I got.

He’s 23-years-old, but given his winding development path, I think it’s more fair to look at him as a hyper-talented 20 or 21-year-old player. For now, he’s doing the core thing I could hope from him, which is playing at the right speed. He’s not meek or hiding from responsibility, and he’s not ahead of his skis either. He’s demonstrating his talent every time out, and has the foundation of a real difference-maker. His tools as an athlete and a passer can allow us to dream big.

That’s it for now.

Happy grilling everybody. ❤️

If you’d like to help me continue churning these out every week, and available to all, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Thank you!

Might be the best BBQ yet

Hi Billy, just FYI I know it is often listed as defensive line height but that measure is the average height for defensive actions against. It’s a good proxy for height but slightly different in that if actions aren’t happening there is nothing to measure.