It's Jover

The Inswinger Era, Saka's levels, Jorginho's anticipation, Ødegaard's movement, Rice's legs, why that first half felt static, Saliba!, Raya's distribution, and a lot more

“To me, boxing is like a ballet, except there's no music, no choreography, and the dancers hit each other.” — Jack Handey

As we inch closer to another transfer window, there is #content to come. We should, however, keep our expectations fully in check. This is not because the squad is full, or because lurching for a quick fix in January isn’t always the best decision. It’s because there is an increasing constraint on our budget: any funds for a top-tier forward must now be diverted to the contract renewal of a fucking set-piece coach. £70m sounds about right.

We have plenty to cover — good and bad, obvious and nuanced, Nicolas and Jover — after the five-goal demolition of West Ham and the sleepy-then-raucous victory against Manchester United. In truth, though, tactical analysis seems insufficient for the West Ham game; the honest, sober analysis of that one is basically “are you serious, Bukayo Saka?”

In one half, he logged a goal, two assists, a drawn penalty, a corner for another penalty, and a generally decisive, low-touch, overpowering performance.

He currently leads the European top-5 leagues in:

Goal-creating actions from live-ball pass (12)

Goal-creating actions from dead-ball pass (5)

Goal-creating actions total (21)

…and he’s done it as a high-touch playmaker, an off-ball mover, an elite corner-taker, a shot-hound, a pseudo-10, a dribbler, or whatever else the situation requires.

It's hard to argue with the peak levels of Vini, Haaland, Rodri, Bellingham, KDB, Mbappé, and perhaps a couple of others. On current form, two global players are performing above the rest to my eye (though Van Dijk probably has a shout too). One has been in that discussion several times before; the other is making his defiant entry.

Now, that’ll show a fairly clear picture: more overall involvement for Saka, and more goals for Salah. But it also shows one of the shortcomings of “radar views” of statistics, as no one view is all-encompassing: proportionality. Goals (and the shots they require) matter most, by far, and this can give us a false sense of equal weighting with other stuff. This is to say: yeah, Salah still takes it; he’s been frustratingly inevitable. But this is the company Saka now keeps.

I’ve been casually researching a longer piece on Saka to help understand some of the little, hidden-in-plainview nuances of his game. As he is still younger than players like Joshua Zirkzee and Jack Clarke, he still has an improvement or two to make, too: things like receiving crosses at the back-post, or the speed of his first-touch strikes in the box. The team can always work on improving the conditions around him. But with every year, a new weakness gets deleted from his game, never to be seen again, and a new level emerges.

Joleon Lescott, who is part of the England staff, was asked on The Rest is Football which talent impressed him most in senior training. I think he put it best.

“Saka and Kane let me know they were world-class, not just because of their talent, everyone can see that, but their consistency. To see Saka control the ball, as simple as this sounds, to make the right decisions — not nine, but 10 times out of 10. If you showed him inside he’d get a shot or a cross off, or if you showed him down the line he’d do the same thing. To see that it’s like ‘that’s why you’re world class.’ Not because you can do the most tricks, because you make the right decisions all the time.”

Saka also had a big hand (foot) in the story of the week.

👉 Corner Kings

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Arteta traces his focus on set pieces back to the manager he played for most: David Moyes.

“Probably when I was a player because I was at Everton and I understood how important they were, how difficult it was for the opposition as well,” said Arteta. “When I came here, we had a period in some big matches as well we suffered, then we were out. Then I went to [Manchester] City and I immediately realised that we have to do something about it and I continue to do that.”

Arteta repointed a question about being the “corner kings” of the league by inferring that it was a wider push toward marginal gains in every direction.

“We want to be the kings of everything — at set pieces, the best in the world, at high press, the best in the world, attacking open spaces, the best in the world. We want the best atmosphere in the stadium, and be the best at everything.”

I’m no Set Piece Sicko (have you followed Jake yet?), so outside of the nitty-gritty tactical stuff, if we’re going to oversimplify the reasons for Arsenal’s success, here are three I’d offer.

Focus — Somebody once told me that your priority list is not your priority list — your calendar is your priority list. And within areas of our control, at least, there’s often a huge delta between what people say they find important (“stated intent”) and what they actually spend time on every day (“revealed intent”). In the same way, it’s one thing to say you care about set pieces — it’s another to invest in coaches, give those coaches a seat in transfer dealings, vacate the technical box for said coaches, and take hours away from general training to show you care about their efforts. There is a cost there. A team must acknowledge and pay.

Players — As a corollary, this focus has trickled down into the squad that Arsenal have built. This includes a lot of big, physical players. Here’s what I wrote after the Merino deal went through.

Whatever nits there are to pick, there is something I really like about this deal, as well as the one for Calafiori. It presents a clear “theory for the case” for how Arsenal, and not others, can win the top prizes. The club is pushing its stack of chips into the middle of the table on Arsenal’s clear advantages, instead of spreading them around on the theories of others. No half-measures are being taken. Amongst top, high-possession clubs, Arsenal can be the most aggressively pressing, physical, imposing, tall, set-piece dominating, bullying team in the world. If it works, it’ll be hard to replicate.

But it also involves something else — sheer consistency of application. In Saka and Rice’s case, there are other players who can generally hit a ball as well as them. But these two aren’t really flair players; they take a certain pride in the workmanlike, reliable technical application of their skills, and can do it reliably.

Communication / Details — I think Arsenal have some things to figure out with communication on defensive set pieces. But in attack, you’ll see how clear the chain of command is — how the information flows cleanly through the different parties, and how everybody then acts as one. Football is played on an enormous, loud pitch, with players often out of earshot of their managers. I think “intentionality of communication flow” is an aspect of the game where there are still marginal gains to be had.

That’s all a long way of saying: Arsenal are tall, and the deliveries are ridiculous — and ridiculously consistent.

This is also why I generally advocate against dropping back into a more passive pressing shape. Dead balls are a numbers game, and maintaining the high-possession, high-line side helps tilt the odds toward you.

It’s no surprise that this recent uptick in dominance came after a quiet international break for our two corner-takers (Saka and Rice), allowing them to rest their legs, coupled with a torrent of corners. The team earned 23 in all against Manchester United and West Ham.

Corners are complicated and chaotic. They should have elements of stealth and surprise to keep the opponent off-balance. That said, Arsenal seem particularly effective with a specific one: in-swingers to players arriving from the back post.

We saw the near-post variety on the Timber goal against Manchester United.

A few minutes later, Arsenal almost scored another, eerily similar one.

Timber’s goal didn’t look too different from his shot in the 24th minute against West Ham.

Which brings us to the archetypal example.

Six Arsenal players line up at the backpost. Some of the West Ham players are “zonal” — see Emerson and Paquetá — while some are “man-to-man” and have specific responsibilities to mark certain players. This is probably the right way to defend Arsenal. But Calafiori runs a “rub route,” and things get crowded in the middle; Gabriel then sprints around the bend, losing Antonio (who should have probably fought over the screen). Gabriel then heads straight to that soft spot between the two zonal markers.

Timber helps with a nudge and Gabriel delivers a glancing blow across the face of the goal.

There’s a reason why there are two steps here: first losing the man-marker, and then attacking the spot in-between zonal markers. Don’t take it from me. Take it from Tony Pulis:

“I always used to hope and pray teams would zonal mark because you have people standing and jumping,” said Pulis.

“When it's a running jump against a standing up, there's not many people who will beat you. Arsenal are attacking the spaces in between the zonal markers and everyone is on the move.”

Manchester United didn’t have Gabriel to deal with. They man-marked Havertz on corners; otherwise, they were hilariously zonal. They are almost locking arms in protest. Hell no, we won’t go!

(They went).

The warning signs were there early for United. You can see what Pulis is talking about below. When a zonal marker starts from a standing position, they have a literal inability to simultaneously a) see you running and b) track the flight of the ball. When you come at them with the full inertia of a run, it’s easy for you to nudge them forward and win position. Despite the cage that Manchester United sought to build around the goal, this was a totally free header.

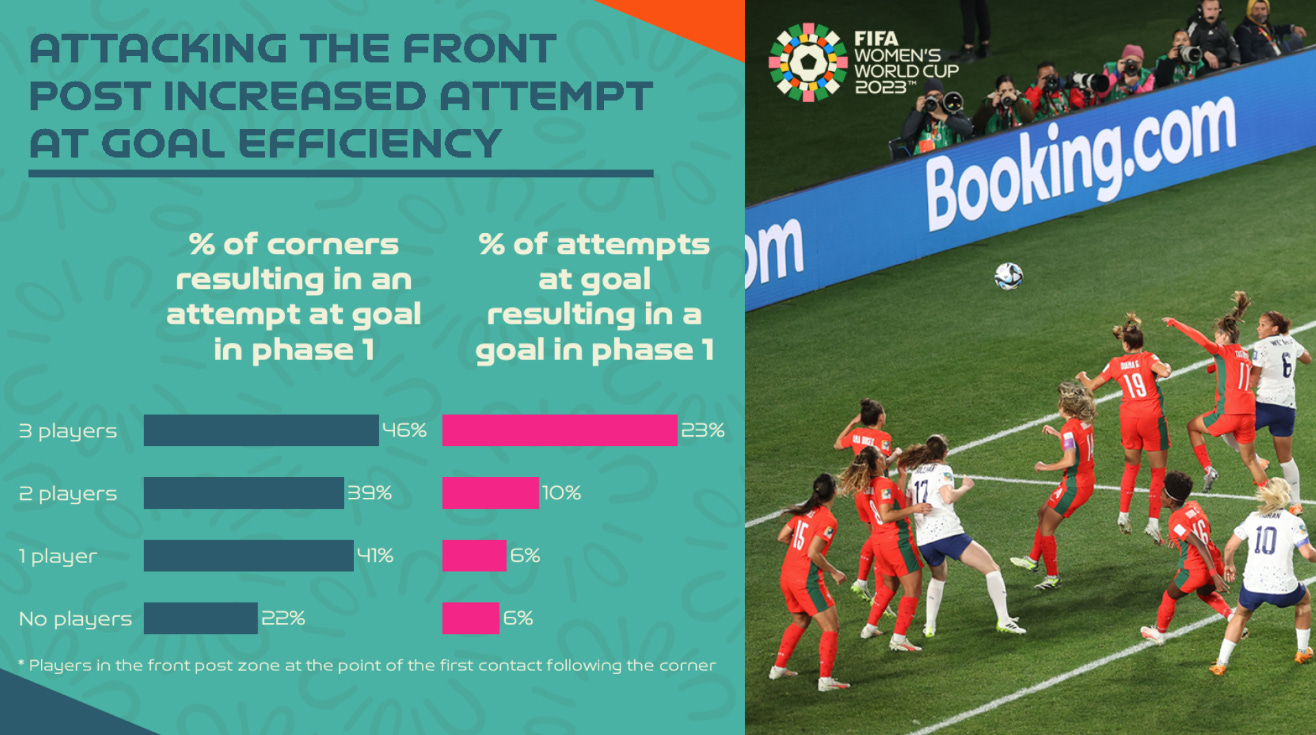

There were many others. Flooding the front zone helps with the numbers, as we saw in this (small sample size alert) in the Women’s World Cup.

There are a lot of complex considerations about shot quality in different areas of the box on corners. So much of it is ultimately about the characteristics of the players on the pitch. Where is the opponent’s weakness? What do they want us to do least?

Try and hit it there.

And what about the delivery?

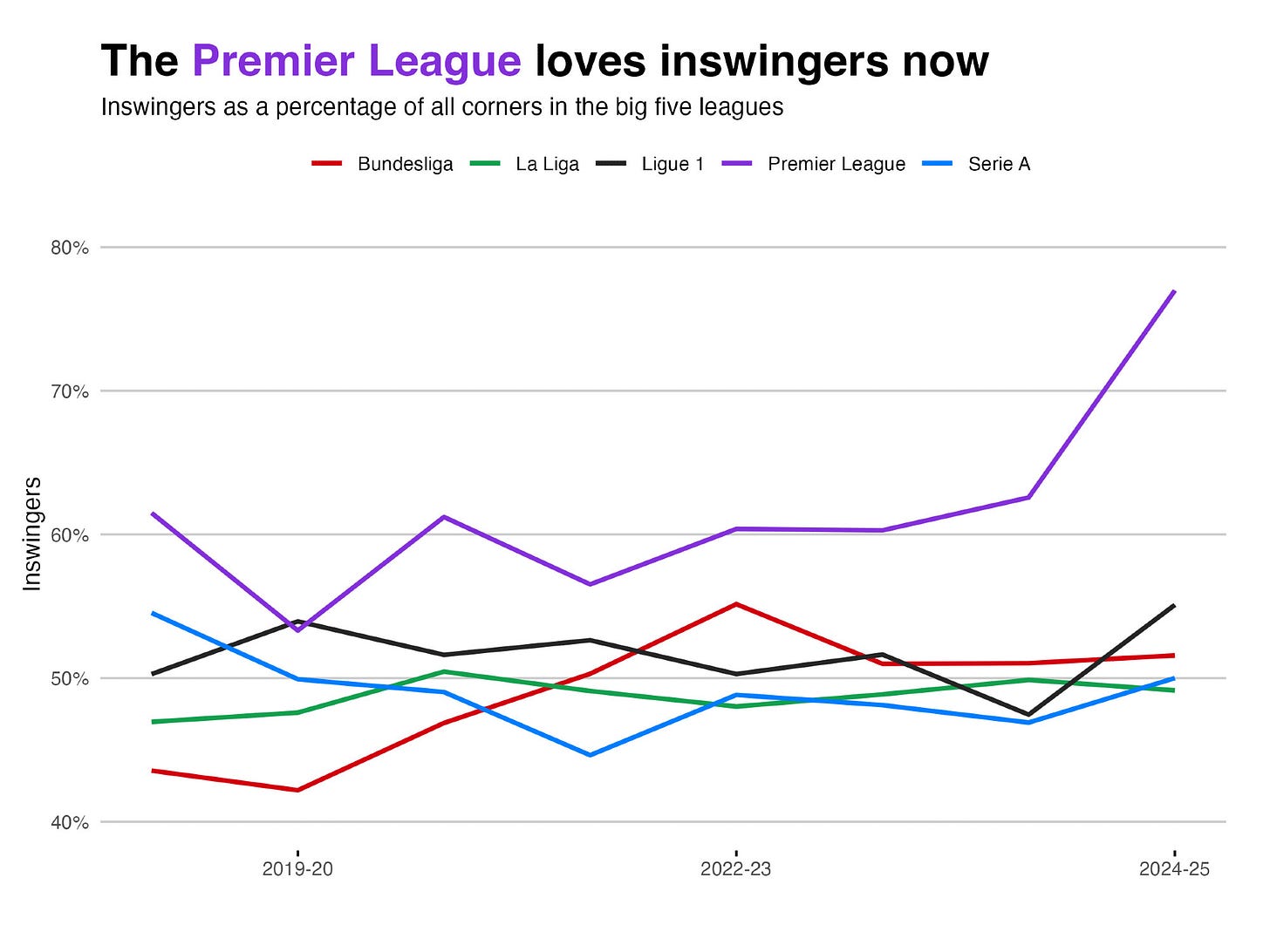

Arsenal are the most extreme inswinger team in Europe right now. For all the complexity and nuance, this is something they don’t budge on.

The only outswingers were three Declan Rice balls from the right corner flag hit during the Bournemouth red card match. That was a special case: the starting lineup was missing Saka, Ødegaard, Martinelli, and Nwaneri.

This focus on inswingers is part of a wider trend in the league. As the great John Muller (follow on Bluesky!) notes:

There are a few interesting factors here.

The first is that you’re generally less likely to get an immediate shot on an inswinger, as The Analyst tells us:

Shots directly from corners are incredibly rare, and even more so when your corners are inswingers. Inswinging corners led to a shot from the first contact 16.9% of the time in the Premier League last season, whereas the first contact was a shot from outswingers 25.1% of the time.

But! It’s a big but, and I cannot lie. The quality of chances are higher.

Shots directly from inswinging corners were higher quality chances than outswingers, with an average xG per shot of 0.14 compared to 0.08.

This makes sense for a few reasons.

If you think about the relative paths for inswingers and outswingers, the degree of difficulty for a good inswinger may just be higher. An inswinger has hazards (also known as players) in the path the entire time it is in flight; if it’s not delivered with enough whip or height, it’s getting stopped with ease. An outswinger is often untroubled until the end, and it may be easier to deliver around the penalty spot.

Many attackers prefer outswingers, as well. It can feel easier to direct a ball when you’re already looking at the goal and can use the power of the ball to blast it forward.

The Athletic’s resident goalkeeping analyst (and former goalkeeper) Matt Pyzdrowski had a counterargument, though.

“As a keeper, I hated inswingers more because the ball is coming towards you and you have a load of people running towards you in a tight area and a lot can happen. Small deflections can make a big difference.”

As Pyzdrowski inferred: it’s not just about the initial action. An inswinger’s path is toward the goal. The chaos that ensues on an inswinger is more threatening. Any miscommunication or misstep is more likely to get punished.

That really tells you what you need to know.

Inswingers are harder to deliver as a corner-taker, but more dangerous when hit well.

Inswingers may be harder to contact as a jumper, but are more dangerous when hit well.

By upping the level of difficulty, you up the reward.

This chart will also tell you what you need to know.

lol:

👉 Jorginho and the value of anticipation

Last time I wrote you, I shared some of my issues with the pressing this year.

Whereas my previous beefs have been mostly on the player-level (small miscommunications, late jumps, Partey’s proclivity to dissolve into the backline), some of my beef against Sporting was more philosophical: I generally believe in a “press or don’t” approach, and don’t like the in-between stuff that we saw so much from Ten Hag sides. It means your first line is too easy to bypass and you’ll be running a lot for no reason.

I can’t really argue with the results [against Sporting], especially in the first half. Instead of having Partey join all the way up high, he’d patrol the middle — which would generally mean that there is a free man in build-up, but that Gyökeres would be marked by both of our CBs and our midfielders would be around to pick up second balls. The gamble was that the first line of press would still force a long-ball, and then the backline have the numbers (and quality) to win it. When it worked, it looked like this.

In a positive situation, the mostly man-to-man but kinda-zonal press looks like this — in which the press is aggressive but outnumbered high, Partey is in the middle covering space, and Arsenal look to win the battles from there. In this example, Sporting can’t get past the outnumbered Arsenal press, long-ball it up to a fortified backline, and the second ball is secured.

Though the shape is different, this isn’t wholly different from what Liverpool have been doing this year: pressing with the forwards, yes, but being fairly conservative elsewhere, and always ensuring that they’re not emptying out the midfield.

In the less positive situation, it looks like this, though. The free man is found, and it’s easy to play through the middle.

It’s always worth remembering that professional athletes are in their own stratosphere; many overestimate their closeness to these cyborgs. That said, as far as mid-range running is concerned, I think Jorginho is a rare case: he is actually One of Us. Do you have any idea how smart (and coordinated) you have to be to be in contention for a Ballon d'Or while also being One of Us?

This brings us back to my bugaboo: the relative committedness of the press. With a 32-year-old, famously slow, slight midfielder who is working on his coaching badges, it was worth considering how “maximum” the pressure would be against West Ham. We got our answer pretty early. See:

He is always going to try to pick up a step with his anticipation. It seems to almost be a point of pride that he looks to arrive in the same positions a quicker player would.

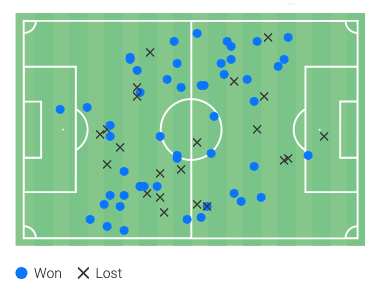

In all, you can see his total actions across the pitch.

“He is a refined player, probably not understandable by everyone,” said Maurizio Sarri. “You have to set your eyes on him and only watch him in the game. He is so good and intelligent that he makes everything seem easy, rarely anything spectacular remains in your eyes. This is its greatness."

After extolling his virtues in possession, Thomas Tuchel also made sure to mention the other side.

“As well as this, he is relentless in defence,” said Tuchel. “He wants to help everywhere on the pitch. He has a huge ability to run a lot for the team. Maybe he lacks the high speeds, but he compensates with a lot of work-rate and anticipation in his defensive work.”

Even as his speed wanes even more, this obstinance continues unabated.

Here was him stopping a counter on a quick read.

Here’s him dribbling away from an encounter with Summerville.

…and in the fourth goal of the game, it was his repeated intensity that eventually won the ball — setting off a quick (and ingenious) Ødegaard touch, followed by a “weak”-footed blast over the top by Trossard, who is good at this kind of ball when facing play.

His primary value is with the ball, of course.

Sometimes it feels like our other options at the #6 can lean too safe or too aggro — their weighted dials go 0 or 10 — but Jorginho is a master at clicking the dial to all the numbers in between, depending on the situation.

You can see how laterally free he was against West Ham.

You can also see how different his focus can be from Partey. Partey relentlessly looks to deliver line-breakers to that right pocket. Jorginho is more likely to switch with Rice, and to flow over to the left to help things along over there, or to try out different things. Partey has a hammer; Jorginho has a few other tools.

Back in Italy, Roma's Radja Nainggolan said Jorginho was the hardest opponent he's faced. Nainggolan had an interesting observation about such a slow player: he’s exhausting to play against.

“He always plays in tight situations and passes very close to him,” said Nainggolan. “It's very hard to follow him and stop his plays. You get tired because he moves the ball very fast, but he didn't even move himself.”

Against West Ham, there was urgency and clarity in the team’s play in the first half. While we may associate Jorginho with slowing things down, he does a lot of things like this on regains.

This led to the tempo that bore immediate fruit. Arsenal usually average 5.56 passes per possession in the first half. In that five-goal first-half explosion, the number dropped to 4.61.

He’s so comfortable with the ball in part because of how much of it he’s had over the course of his career. Chicken and egg, of course.

Between 2004-05 and 2017-18, here’s the leaderboard for most touches in a game in Serie A, from Sky Sports.

He’s going to be difficult (and expensive) to replace.

👉 Ødegaard’s horizontal freedom

“Bukayo Saka and Martin Ødegaard linked up beautifully at times and they looked like the side we’ve seen over the last couple of years. It just shows everybody what Ødegaard does for this team, he knits it together ... He frees Saka up and gives him that time in one-on-one situations that you can’t really have unless Ødegaard is playing.”

One of the ways this happens is through endless, tiring off-ball runs. Ødegaard is not particularly threatening as an in-behind runner; it’s hard to remember any time he’s been hit with such a ball. But defenders can’t leave him totally free, and Ødegaard is more than happy to do One Million Full-Sprint Decoy Runs that pinch the full-back in a step or two. Watch Trossard gathering the ball here:

…now, watch how aggressively Saka can prosecute his 1v1 upon reception.

It’s not the biggest thing, but this is the kind of detail that has been missing from the left for much of the last two years. Rice and Havertz can provide it in theory, and have done it in spurts; to apply this timing consistently, though, it requires such a comfort with the role that the run is starting before a deep receiver even gets on the ball.

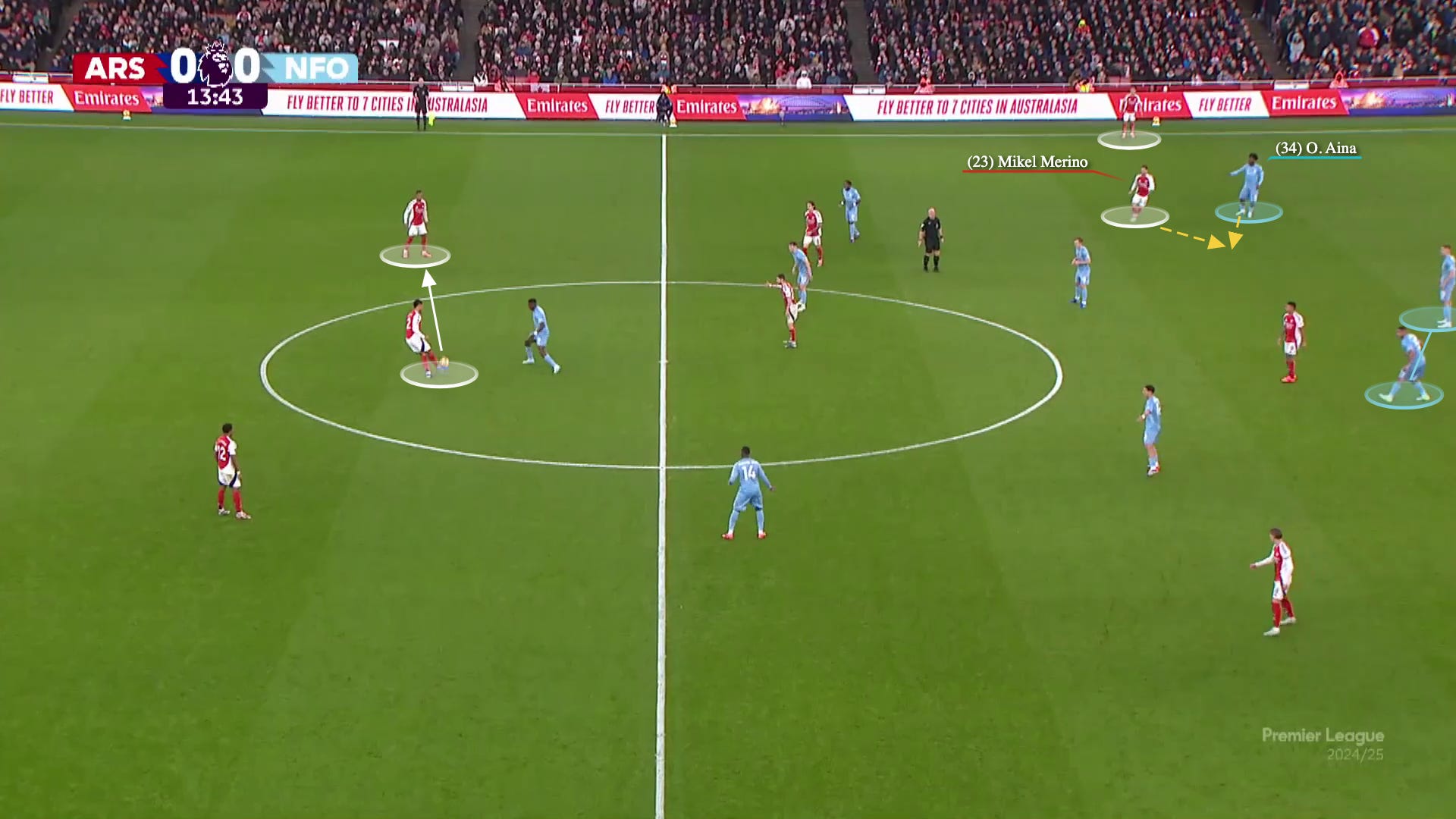

Merino is already showing it in flashes. Trossard was able to take this and push it forward.

But back to Ødegaard.

His ideal role is often a Catch-22. He essentially solved … everything … when he started dropping into build-up last year, progressing the ball at some of the highest rates in Europe. But that came at a cost. For one, it was just too much running to expect someone to do. More tactically, it was tougher for Arsenal to reset into their pressing shape on a ball loss, because Ødegaard was generally further away from his position up top.

Upon re-entry, Ødegaard has generally settled into the broadly correct role. He is not merely parked in the right half-space, nor is he a card-carrying member of the deep build-up committee. He’s generally on the right, but there aren’t artificial constraints: if he sees an opportunity to help the left, he does it; if build-up needs a little dynamism, he does that. But it’s not out of necessity. This is where the additions of Timber and Calafiori have been most helpful.

Here, you can see how things have played out. Against West Ham, he’d stick around that right half-space plenty while Jorginho floated up to the left, but he was also free to problem-solve and exploit little gaps throughout. Against Manchester United, he tried to be available more centrally.

The beautiful second goal against West Ham shows how much this can help to unhook things. After floating into a central area to try and get a shot off, Ødegaard stuck around as things reset. Calafiori was up in the left half-space, so Rice dropped down as a fake left-back. There were some little passes over here.

Somebody commented on Bluesky that Havertz specifically floats into the spot that Ødegaard vacates, and I’ve been seeing that ever since. He’s like a seat-filler at an awards show.

In this case, that spot that Ødegaard often goes to receive is open; Rice resets to the LCM, Calafiori drops down, and Havertz receives a ball from Saliba.

This leads to one of the prettier goals in recent memory. Saka receives it, passes it, angles his run perfectly, and Ødegaard flicks it over the top. Havertz is now entering the central area from deep. It’s a barrage of questions asked of West Ham, all at the same time.

Saka does two crisp touches; Havertz is running through the middle, just as he was on Martinelli’s goal against Sporting, and Trossard bats it home.

A similar situation reappeared against Manchester United. The shot didn’t fully come off, and Saka was ruled offside (I’m not sure — it was close), but three defenders were zapped out of the play in a single pass-and-move.

For whatever reason, Ødegaard didn’t fully look at his physical best against Manchester United, to my eyes; he wasn’t driving with quite the same ferocity. But he still pulled off a few moments like this, where he was again floating horizontally and providing the central access that has been so lacking in this period.

👉 Rice’s running and kicking

Speaking of physical returns, Declan Rice has had a brutally demanding year. He just does so much running, and neither Arteta nor England rest him much. By his standards, there was a touch of lethargia in his early-season performances. He also broke his toe.

Just based on some of his recent carries, it looks like he’s getting his legs fully back.

I thought the deployment of Rice was one of the biggest early-season tactical issues.

Here’s what I wrote after the August start:

The system calls for an elite ground-coverage #6. At this stage, Partey isn’t that. Oddly, he’ll be better against top teams when the block is closer and the press is lower. Less distance to cover.

Rice is that. But because of his positioning in attack, he is often far away from the ball and catching up to the play. There were several plays where Arsenal lost the ball and Rice was our highest player. I, uh, don’t really want Rice to be the highest player on a ball loss.

This space is being exploited. This leads to some cascading confidence issues where the press isn’t as fierce or committed as we see otherwise. This is central to Arsenal’s identity.

Final thing: when Rice is super-high and pinning the backline, he can’t really turn and carry.

As an example, look at the distance between the two midfield pivots on a ball loss.

That image shows how clearly an in-possession objective (get the LCM high) can impact the out-of-possession success (Rice is AWOL). There is a solution. From the same piece:

I'll write about it, but we've been pushing Rice up into the fake-10, with Timber or Zinchenko behind. Last year, Rice eventually stayed back with Jorgi, and the LB (Tomi, etc) went up into the half-space. This kept Rice's distance to Jorginho closer. This game had me thinking that again.

Last year, the coaches saw this vulnerability with Jorginho, and dropped Rice low to protect him upon ball losses (and Jorginho was also careful about said losses). They pushed the left-back up into the line. It’s time to do that kind of thing with more frequency.

This has been much better — particularly in these last two games. Here’s a look at his received passes as the LCM against Manchester United.

We saw it almost immediately. Here, Zinchenko floats up high into that half-space, Kiwior moves over to left-back, and Rice is an auxiliary CB. This allows him to roam if needed, carry if needed, and most importantly: be back to disrupt a potential counter.

That’s OK in spurts, but you ultimately want him a bit higher so he can snatch the ball back immediately and disrupt the opponent’s midfield. Especially in the first half, he was just a typical double-pivot midfielder instead of the Havertzy shadow-striker role that we’ve often seen him play.

He still had the freedom to push up, to be sure, but he wasn’t in a primarily off-ball, “parking and pinning” type role. He’s providing options in slightly deeper areas than he’s sometimes seen otherwise, which gives him real estate to carry.

The result? He’s not desperately trying to catch up to the play when the opponent gains possession.

Here’s a messy bouncing ball situation.

Instead of him being way ahead of it, he’s behind it. He snuffs it out and delivers a through-ball on his first touch.

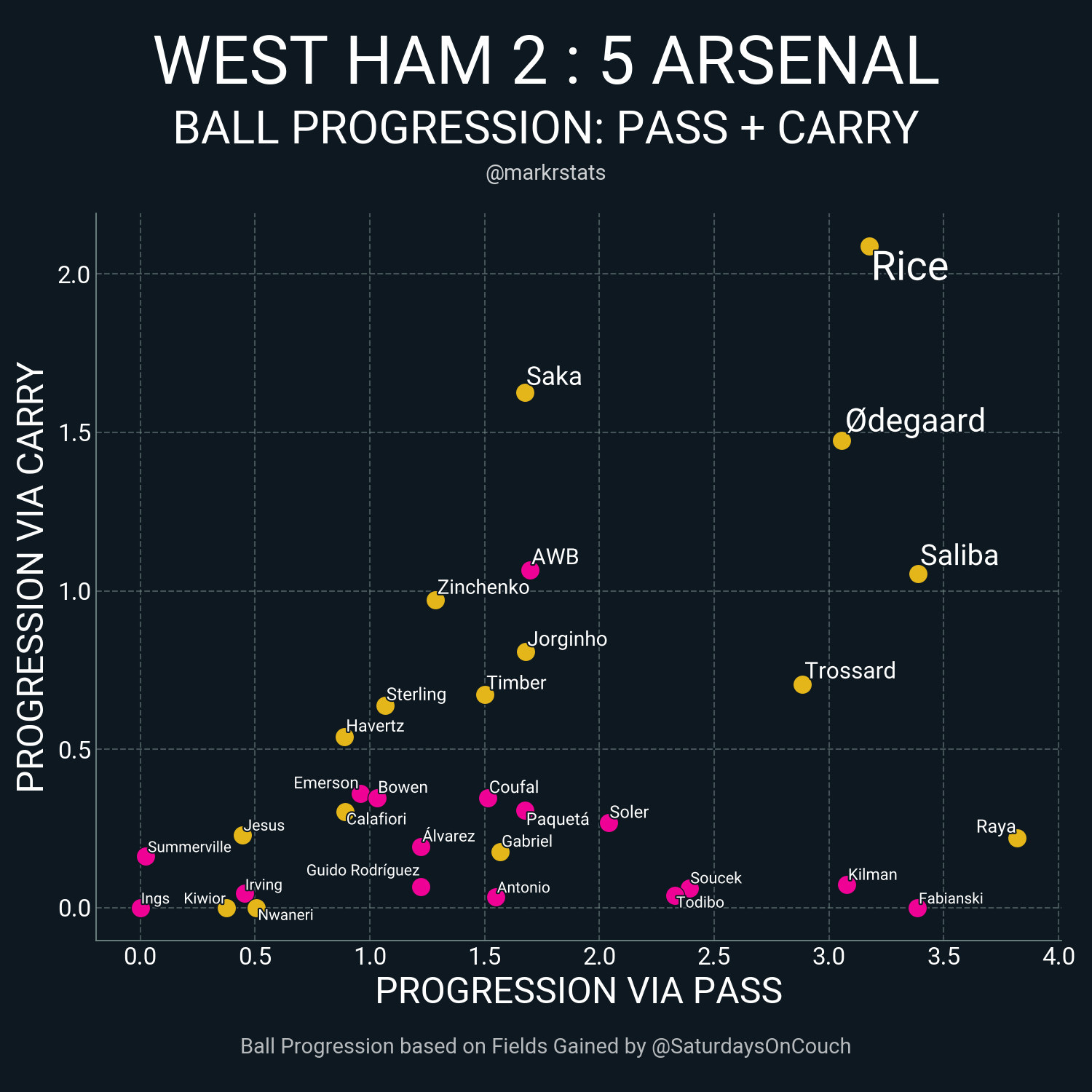

The pass-map against West Ham showed movement both deep and high, as well as a lot of competent switches out to Saka.

He was the progressive star of that day, which you wouldn’t usually associate with that LCM role.

Things are trending upward there.

👉 Adventures in build-up

Against West Ham, the build-up shape was what you’d expect from this team generally. Raya, Saliba, and Gabriel would feed into Jorginho — but aside from that, the full-backs could pinch in, drop back, stay wide, and Rice, Ødegaard, and Havertz were floating around to find gaps. Rice generally played the role of Actual Double Pivot for much of the match.

The build-up against Manchester United was a little bit more complicated. The opponent, led by newly-minted Ruben Amorim, was well-disciplined and difficult to break down when the score was even; the 3-4-3 (5-2-3) had the right amount of activity, the wide areas had a lot of bodies and backup, and most of their starting eleven could actually run. It was tough because it was tough. The opponent has a say.

This led to a lot of poking and prodding to try and find vulnerabilities. If I had to say anything was a base formation, it was probably this.

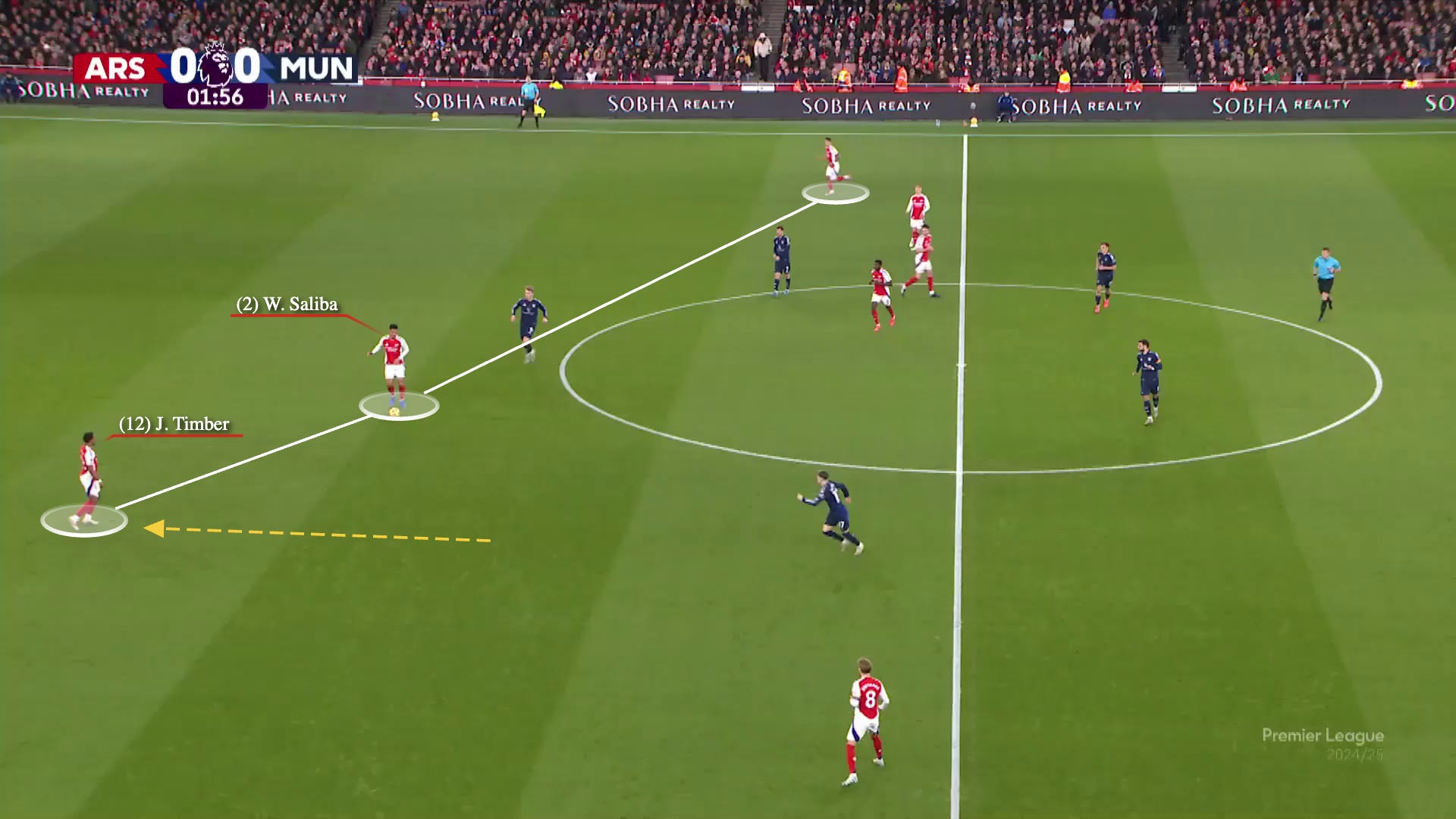

Rice and Zinchenko were frequently switching and floating, and then Timber again differed from White by pinching closer into the midfield and keeping his options open. On top of this shape, Ødegaard and Havertz would drop in at will to overload the midfield.

A lot of last week’s newsletter was about Timber intentionally crowding Saliba’s space, and often even dropping behind him. This is an effort to draw the opposing winger out, which opens up lanes through the middle and keeps them further away from Saka for an eventual reception. It happened again.

Within two minutes, we’d already seen Rice as an LCB, Zinchenko as a #10, Kiwior as a left-back. Now we’re seeing Ødegaard go over to the LCM spot, Saliba move to RB, and Timber at RCB.

Here’s an example of the swirling structure working in fairly novel ways compared to previous years. It illustrates how Arsenal are not unchanged.

The back-three is staggered from the midfield in this example. Instead of staying in the right half-space, Ødegaard pushes left to help overload that side. Timber, again, is closer to Saliba than we may see otherwise.

Once the ball makes the rounds, Timber goes to fill Ødegaard’s spot, which he now does often, and looks to carry through the middle. It doesn’t work out in the end. But it shows potential.

In the end, the play in the first half wasn’t good enough.

To my eye, the distances looked good and interesting. This season, Arsenal can too readily dump out the middle in the middle third when Havertz isn’t at #9; other than that, the structure has felt consistently good, but not always the performance. Parts of last year irked me more. So what gives?

For one, play was too slow. Whereas the squad was a perfectly tuned machine against West Ham, there was more dithering here. In the first half against Manchester United, the team averaged 6.75 passes per possession; that number against WHU was 4.61.

The team was more horizontal. They tallied 112 lateral passes in the first half (the average this year is 95), but only 17 progressive passes (the average is usually 30).

Raya was fairly conservative, going long instead of being overly-risky in the back. With Manchester United playing in that five-back, they usually had a +2 or +3 in the backline, which means that it wasn’t tough for them to dispatch these.

When it came time to hit that aggressive pass, they were often missed.

Nothing particularly complicated. These eventual breaker balls were just a little late and overly-telegraphed.

It led to possession spells that were a little slow getting started, and then were interrupted before they started converting into final actions.

On the other side, Amorim has already installed some Sporting-esque passing structures and — surprise — the Red Devils have immediately looked more competent.

Visually, the Arsenal press immediately came out flying, but statistically, it was pretty conservative in detail, and had some relaxed triggers.

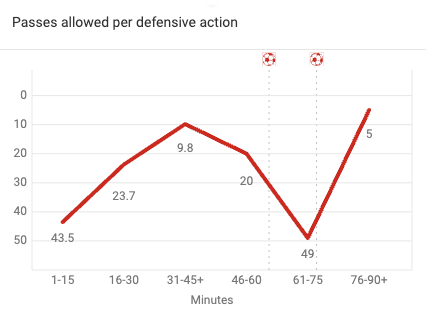

For example, PPDA is an imperfect measure of the intensity of a team’s press. The lower the number, the higher the press (in theory). In the first half, this number is usually at 10; against West Ham, with Jorginho flying high, that number was 5. Against Manchester United, the first half number was at 20.7.

The press looked a bit like what was used against Sporting, which makes sense given the systems (where did Amorim come from again?). In the midfield, Partey had a maximum “line of engagement,” which I believe was tactical and instructed. With United looking to pass around and then go long to Højlund, Arteta didn’t want to empty out the midfield for second balls.

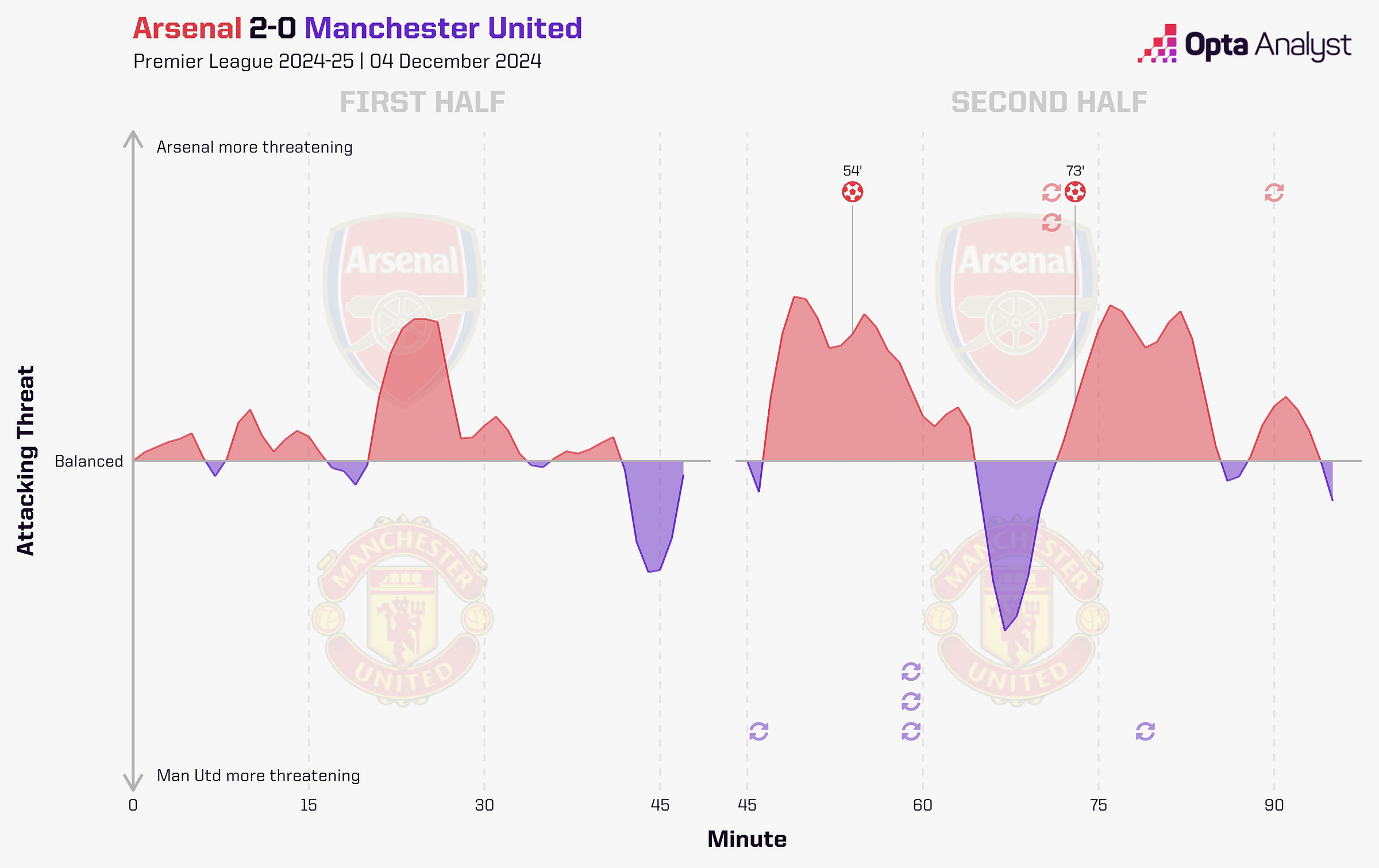

Manchester United wound up “defending with the ball” for much of the first half. They didn’t look particularly threatening but they dulled the Arsenal threat as a result. Here’s Arsenal’s possession throughout the match.

Maybe I should rethink my somewhat straightforward, impatient desire to go aggro man-to-man across the pitch. After all, one could argue it was the best defensive performance of the season. Once United got through the gears into the middle-third, they were rendered toothless; in all, they logged six touches in the attacking pen, the fewest Arsenal have allowed all year.

Amorim saw the fruits of his work in back, but not as possession progressed.

“We work a lot on building up. You can see the structure, you can see the idea, you can see the bounce when the centre-backs go to the midfielders, you can see that. But in the last part or last third you can see we need to improve, be more aggressive, more ideas but that part is more difficult to improve without a lot of training.”

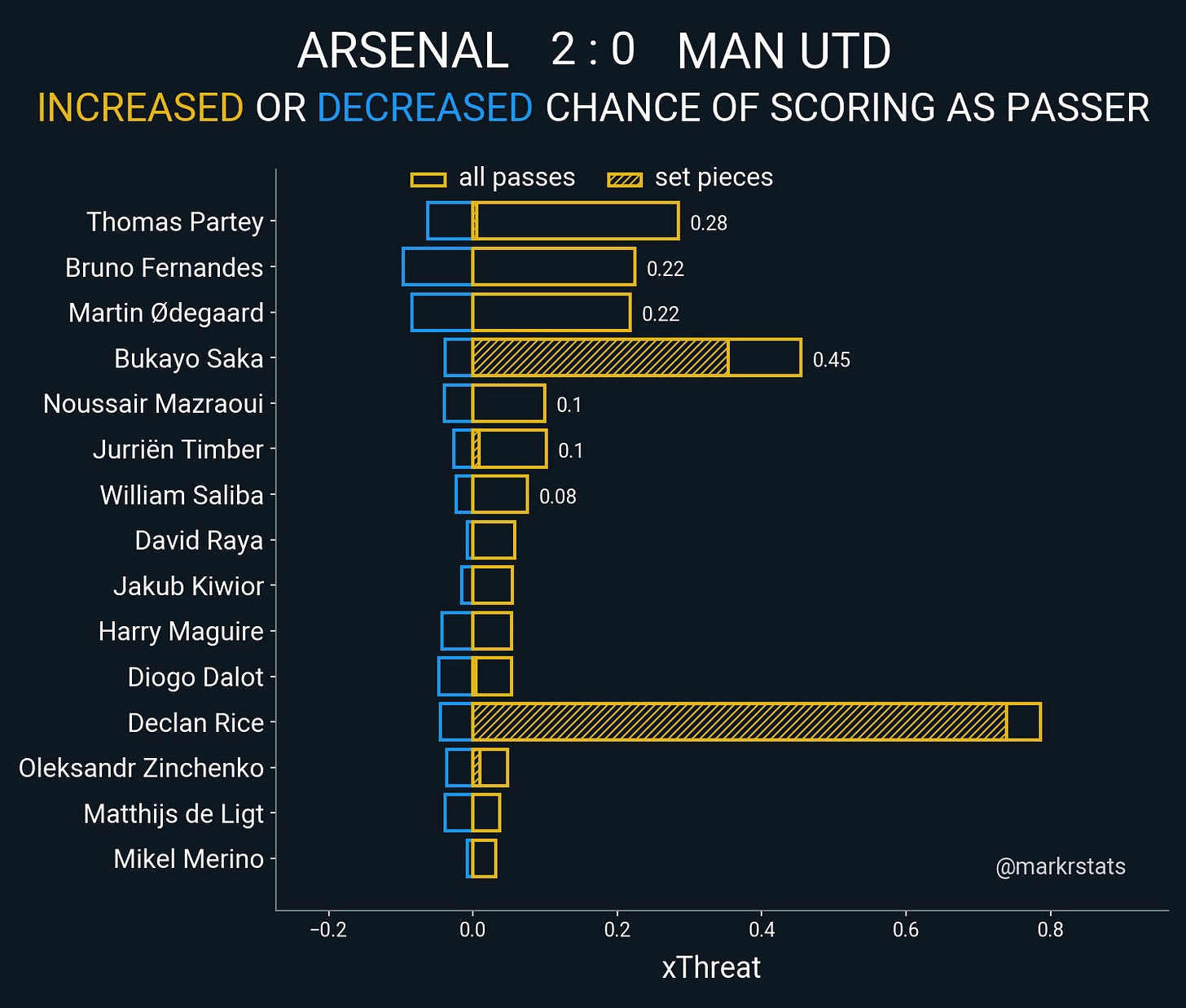

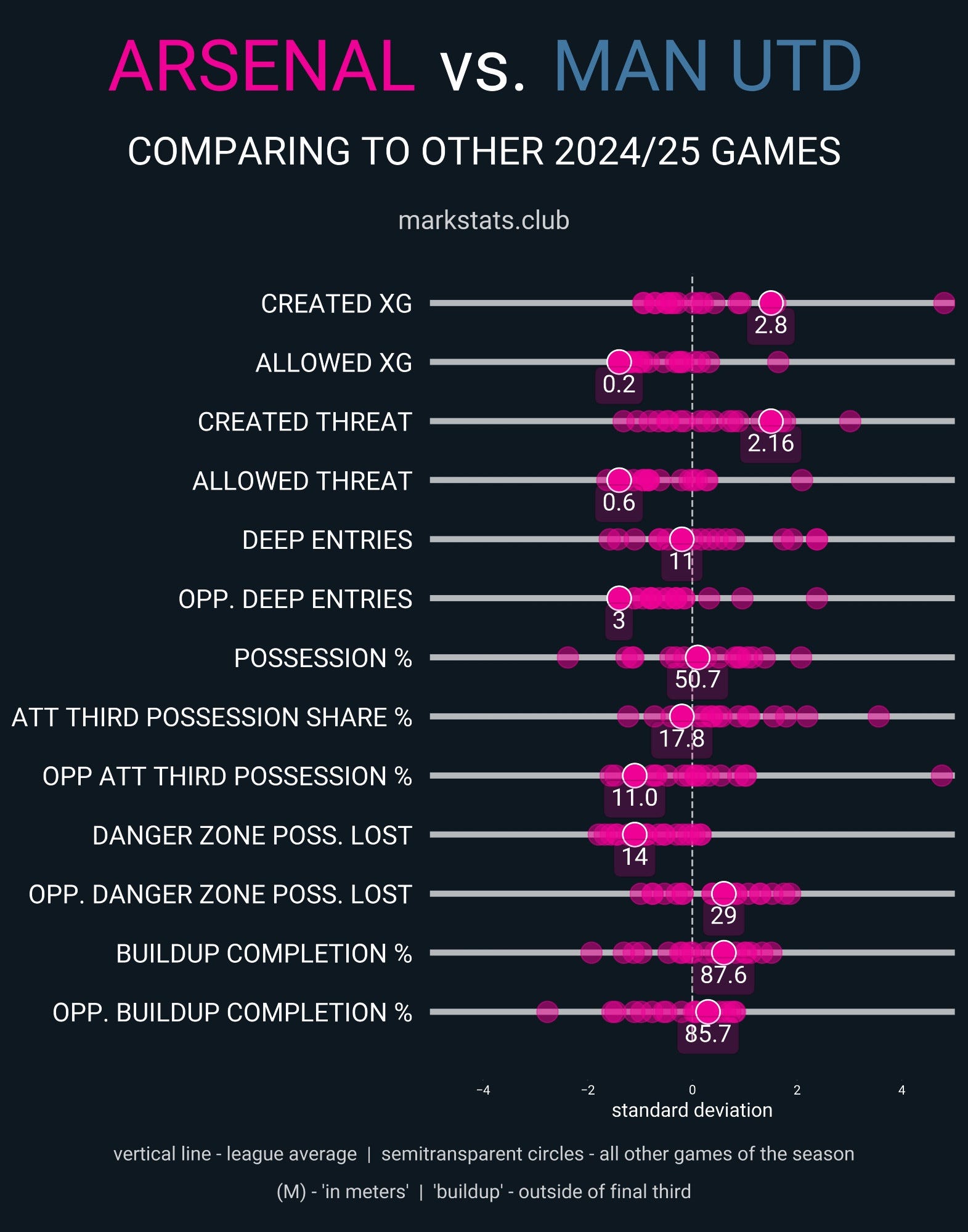

Here’s a great chart from Mark (follow!).

The reason for this?

Yeah, Saliba probably had the most to do with it.

He was assured in back, but he personally interrupted a lot of the United middle-third play, resulting in six recoveries around the half-line.

I liked seeing Kiwior get more time. As I wrote before the game:

Happy anytime Kiwior gets to play LCB (you know, his position) alongside Saliba. I remember him doing it against Preston (2 assists) and a 5-0 against SUFC, but barely otherwise. It’s kinda like how we barely saw Vieira inside of Saka. Partnerships/dynamics can have a big impact on our impressions.

He won each of his defensive duels (6/6) and had some moments of confident savvy back there, like when he chest-passed one back to Raya in a crowded box.

He contributed to some of the spells with lower possession. The team logged the most long-balls of the year (73), and many of them weren’t all that strategic — they were just hitting them over the top to see what happened.

But as the game progressed and United were forced to push more players up, some of them started hitting. Kiwior has a lot of skill here, and he hasn’t been able to show it off enough.

Perhaps the club had higher hopes about some of his other uses (left-back, even midfield cover), which limits some of the impact he can make; his athleticism is kind of complex and not easily discernible. He can gallop at high speeds but there are certain changes of direction where his hips look stiff. But there’s not a lot of time on offer behind Gabriel and Saliba, and this simply looks like a strong CB to me.

The other reason some of the possessional stuff took a while to get going? I think the team is growing dependent on Calafiori in a way we wouldn’t like to admit.

I gather that the fanbase was unsatisfied with his game against West Ham, which is understandable — he made a mistake or two in possession and didn’t lock down the back-post when Wan-Bissaka ran behind Trossard (Trossard and Calafiori can have the same problem with blindspots; Martinelli decidedly does not have that problem).

But watching back, he is so additive to possession. Whereas Arsenal can have some overlapping passing profiles, Calafiori is kind of his own thing — a battering ram, impatient and vibrant with ideas, that warrants the suspicion of the opposing press. This drags and moves lines around, creating space for others.

Up top, his comfort in all three areas (wide, deep, in the half-space) helps grease the wheels of movement.

Zinchenko has been playing a mature version of his role; December seems like a good time for him to get minutes. I’ve been worried about Calafiori’s workload and playstyle, so beggars can’t be choosers when he is eased back gracefully.

But I just looked through the results, and yes: Calafiori’s record in games that stay 11v11: eight starts, eight wins. This includes multiple five-goal displays.

👉 Raya’s distribution

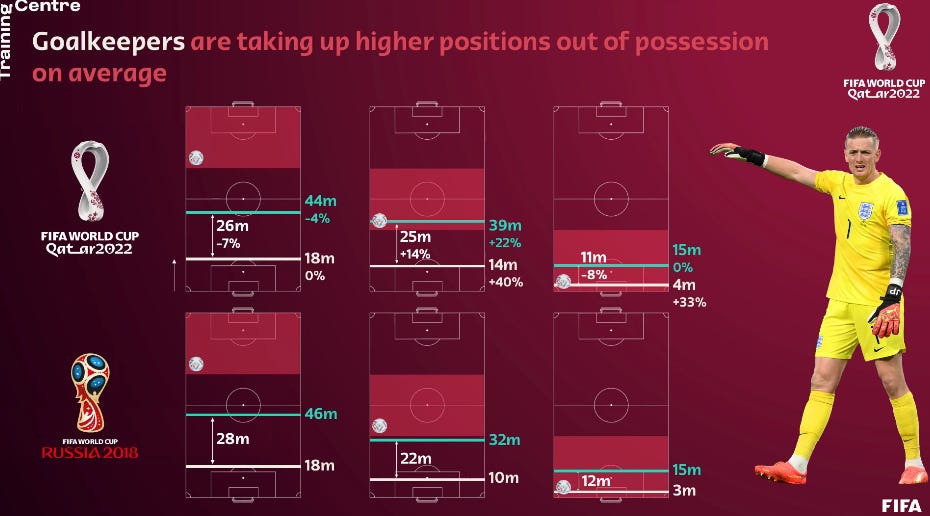

It is not news to say that goalkeepers are pushing up higher than before.

This graphic from the FIFA Training Centre shows how that is especially pronounced in the middle third, where keepers are more likely to join possession.

In the span of four years at the World Cup, keepers almost doubled their involvement.

Their framework for distribution offers a helpful way of looking at the skills that a modern keeper must master.

That framework includes:

Play around and support (for example to a centre-back)

Play through (for example to a central midfielder)

Play into (for example to a full-back in a relatively high position)

Play onto (for example to a centre forward)

Play beyond (behind the opponents’ defence)

Goalkeeper distribution often gets simplified into “good with the ball” or “bad with the ball,” but there are a variety of passes that make the job difficult, and players have different aptitudes with them.

Raya’s distribution has been a big part of the more recent spells of production. Especially once goals get on the board, the opponent is forced to leave their hidey-hole and start applying some pressure. Some of the more satisfying passes of late have come from these moments.

Here’s West Ham generally going man-for-man when down. Carlos Soler can already sense what’s wrong.

Havertz dropped into a zone with Álvarez and can simply outrun him into space.

That was an example of “playing through.”

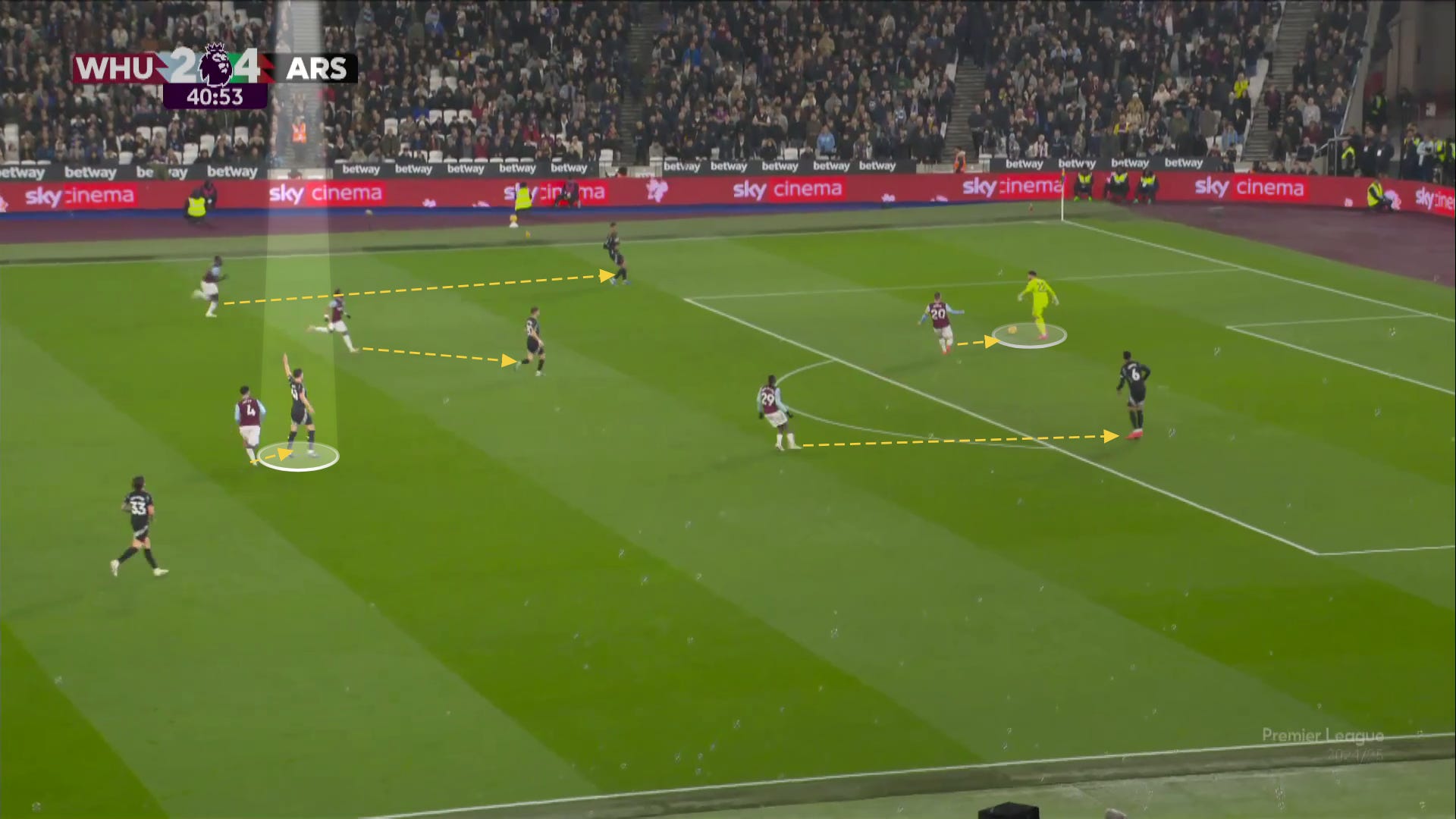

Next, Havertz and Rice essentially switch roles. Havertz drops all the way to drag the slow West Ham midfield down. Nobody switches over to Rice, and he’s free to carry all the way forward.

Here, West Ham goes man-to-man, but like Arsenal, they don’t want to leave an advantage for the opponent in the backline. That usually means that one player is free in build-up, but they are hard to hit because it requires a little clip. Rice sees who is free.

And Raya flips it over to Timber. This is an example of “playing onto.”

Timber has been helpful at interchanging with Ødegaard, floating into the free areas while the captain moves around.

For the third goal against West Ham, in which Saka drew the foul in the pen, Raya “played onto” — hitting it up to Havertz, with Ødegaard sweeping it up and knocking it up to Saka for a 1v1. Who needs playing out from the back?

That play offers a distillation of principles. The interlocking signings of Raya and Havertz showed that Arteta wanted to invest heavily in the ability to go long as the situation requires.

In an ideal world, you’re only hitting it long when there’s a specific, strategic advantage to be gained. My take on the play this year is that we’re still leaning on this too much, hitting some long-balls that are clearances by another name. Preferably, you’re just counting the opponent’s shape. If they commit forward, go long; if they stay back, drag them out.

🔥 In conclusion

So that’s that. The overall direction is mostly quite positive, but there are still lingering questions: specifically, the current defensive depth, and whether Arsenal can be vibrant and penetrative enough through the middle, especially without Calafiori. I have also been doing nightly meditations for Raya’s continued health, which feels concerningly like a single point of failure to me.

Fulham have been one of Arsenal’s trickiest opponents of late. This time, they bring along some more familiar faces. If there’s any silver lining from the early-season travails, it’s this: the mandate couldn’t be any clearer. Three points, every time.

Still haven’t thought about a new name.

Fantastic as always Billy. Would love to know your thoughts on Martinelli at mo. He seems off the pace and unconfident...