Lessons from Everton

Was it a dip in form? Was it excellent defending? What has to get sorted out tactically? How should Arsenal attack a 4-5-1 moving forward?

In many ways, analysis of the Everton match is simple. If you face a Premier League opponent who manages to stay disciplined in their block for a full 90 minutes, and your touches aren’t crisp, you generally won’t win.

To help illustrate, here’s the worst graphic I’ve made in my life:

Still, Arsenal is a much better football team than Everton, and despite all the variables in play—Sean Dyche’s practical intelligence, the new manager bounce, the history at Goodison Park, yadda, yadda—this was their worst in-league performance of the season. As tempting as it can be to write this one off as one of those games, it’s still worth examining.

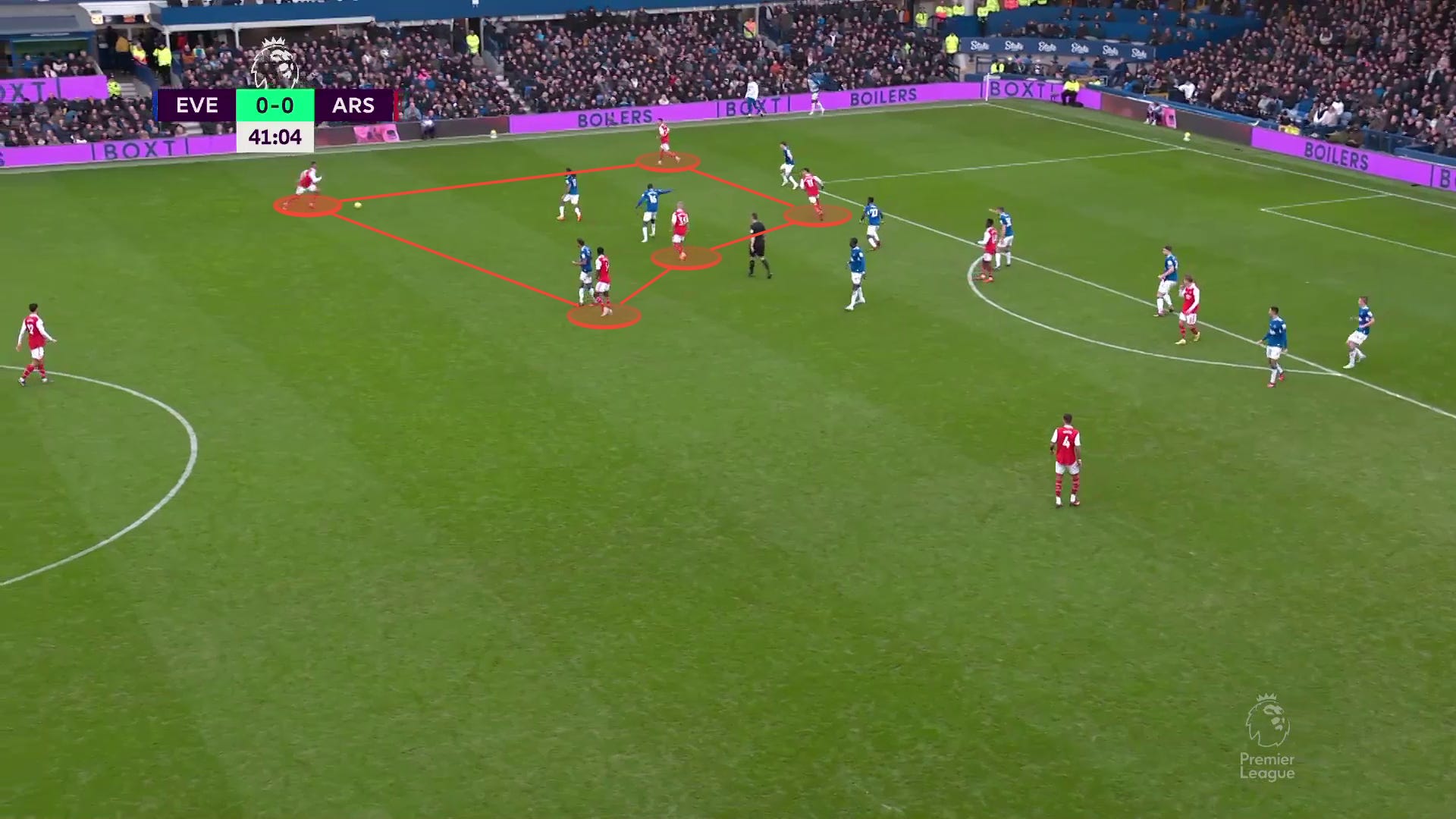

There’s another reason for closer inspection, of course. The tactics used by Dyche had many similarities to those employed by Eddie Howe in the goalless draw against Newcastle in January. Both utilized a low-to-mid 4-5-1 shape; both used their widest wingfielders to double Arsenal wingers and cut off their access to the 8’s; and both tried to show as much compactness and physicality with three midfielders roaming the middle (largely “Zone 14”) as possible. See:

There was nothing particularly novel about either approach, and for those wondering if Dyche uncovered some mystical skeleton key that deactivated the Arsenal Machine, I didn’t see it. They were just ruthlessly effective.

Both teams had three things in their favor that most teams simply don’t: 5 or 6 athletic monsters who are capable of roaming everywhere for a full-90; near-perfect individual defensive performances; and a manager who is elite at drilling these shapes.

While that offers some reason for optimism against future teams who seek to employ these tactics, let’s dive into detail to see how Arsenal fared against the challenge—first on the Arsenal right, then on the left—to understand where we go from here.

Examining the Arsenal right

While playing against a settled block, the gameplan is straightforward, if difficult to achieve. Stretch the pitch to open up lanes; overload wide areas; dribble to drag defenders out of position; transition as quickly as possible before the opposition is set; change the play; score bangers.

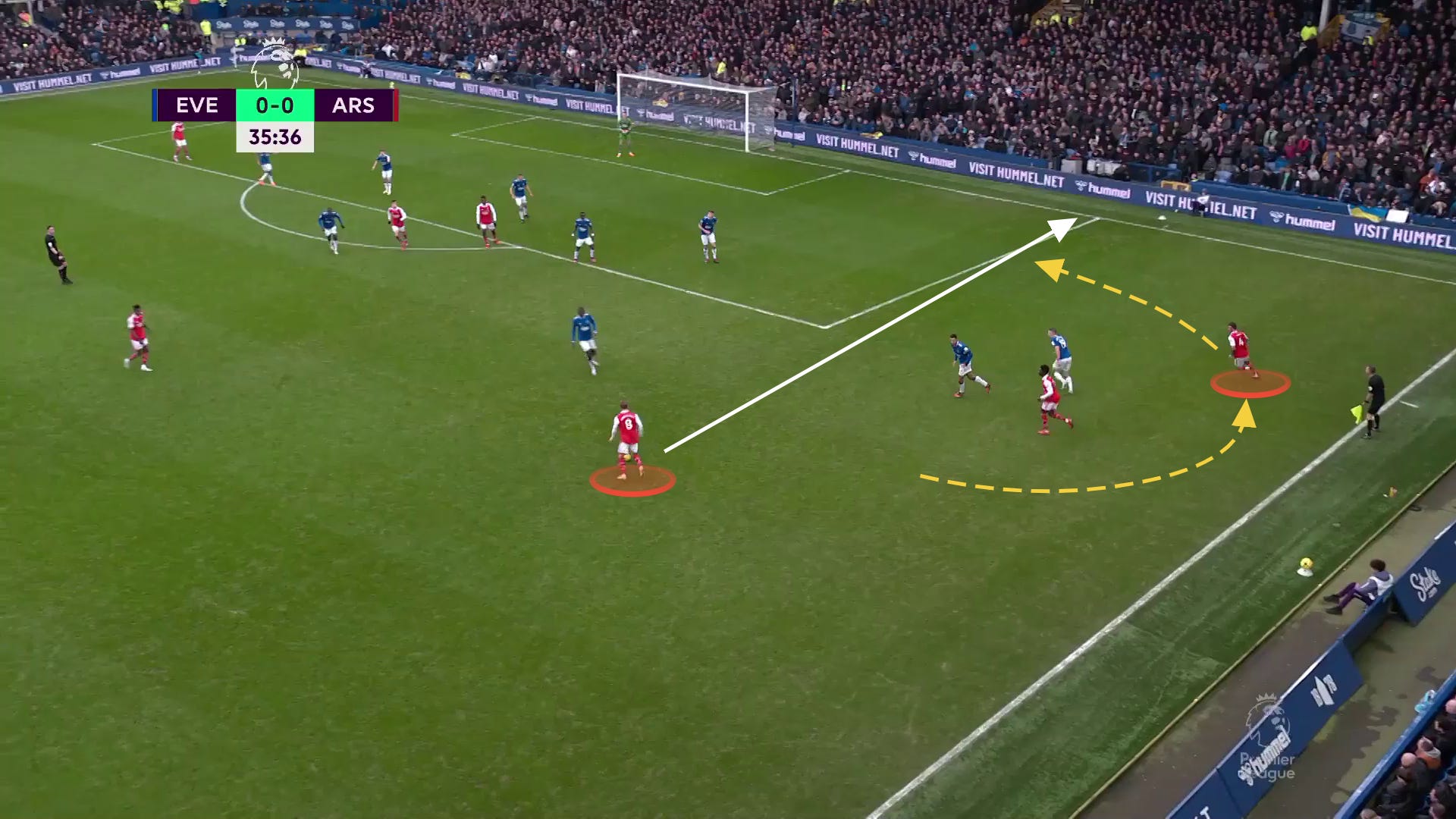

After the United game, I had some concerns that Ted Hag had laid out a new blueprint for defending Ben White that others would replicate. By laying off him and challenging him to make something happen on the dribble, they were able to more effectively crowd the space of both Ødegaard and Saka without further commitments:

I expected this was the case against Everton, even after the initial watch.

After watching back, though, I saw that White generally provoked plenty of individual coverage as he entered the final third. Everton ran at him:

In fact, it struck me how the Arsenal right side ticked off virtually every box you’d want in a tactical execution.

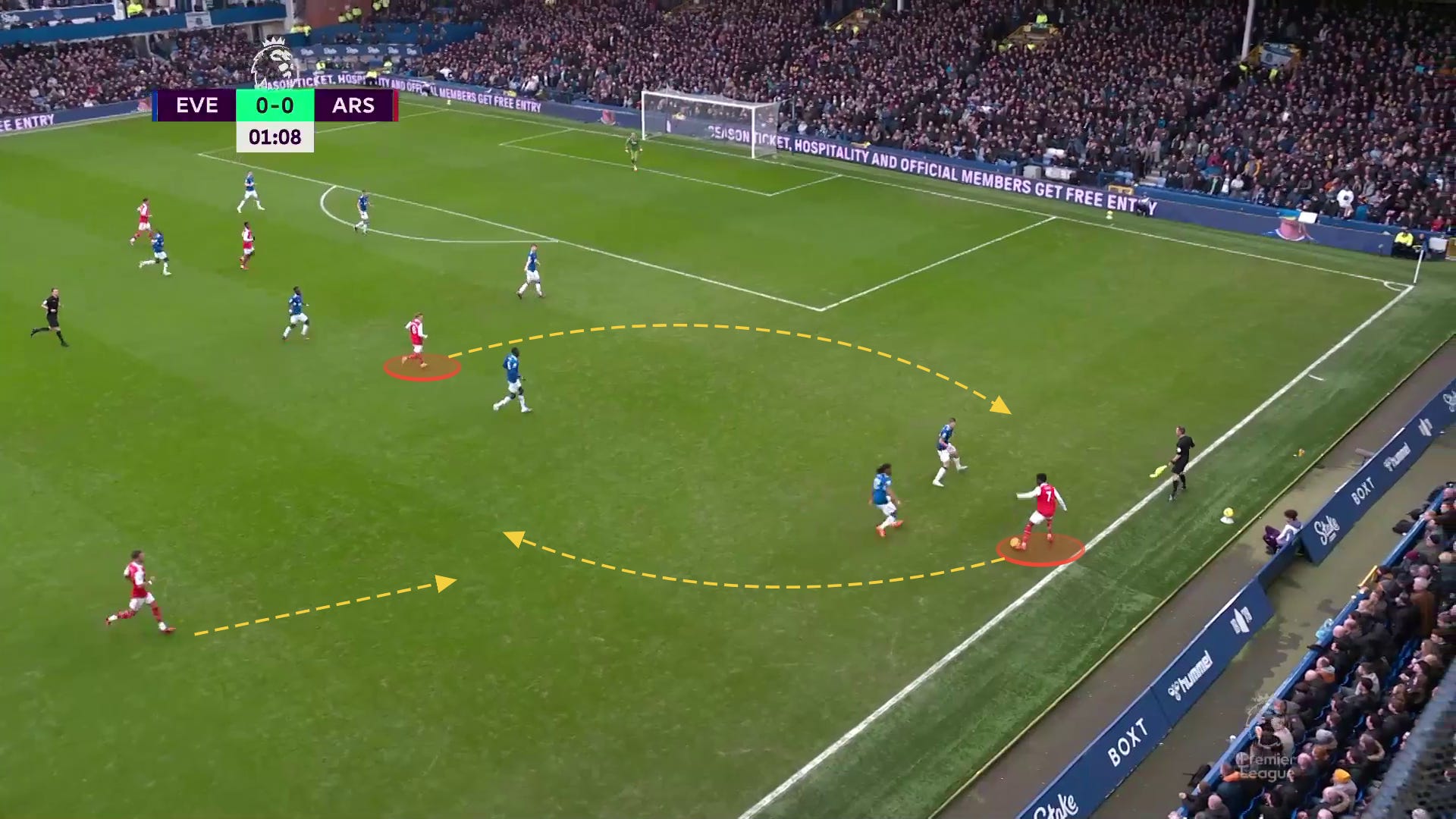

In the first minute, Iwobi is rushing over help to cut off Saka from Ødegaard, forcing him into the 1v2 that we saw countless times on the wing. Saka decides to cut back and drag him through the middle to open up space for his colleagues:

After he does, he hits Partey in the middle to recycle the play, and with Everton now shading to the middle to follow Saka, there are numbers on the outside:

Partey plays it back to Ødegaard, who now has everything you’d want: Mykolenko isolated 1v1; Saka cutting into the “assist zone;” White overlapping and dragging Iwobi with him.

At that point, Mykolenko climbed on Ødegaard’s back and rode him for 10 yards until the ref whistled the foul. It was a good defensive effort, but ultimately, there’s little I’d change with the Arsenal tactical approach here.

A little later, White and Ødegaard narrowly missed out on an overlap, as White tried to awkwardly bend his run to stay onside. It was one of only three missed passes by the skipper:

Aside from that, Arsenal generally pushed in transition on the right. They overlapped and underlapped, although they could have done it a bit more. Saka received high switches from Zinchenko. Partey even got one of his lane-busting shots off, although it ended in a whimper.

So why wasn’t there a goal generated from this side? Boring football stuff, mostly. Saka was his brilliant self, but didn’t hammer home his near-chances. Ødegaard got muscled around before settling in during the second half. White was a little imprecise.

Meanwhile, Everton executed their gameplan flawlessly. No goals for you.

I’m not sure there are any “macro” tactical takeaways here. In general, I think Arteta should try and scheme a little more attacking threat from White’s position, but I’m not sure this game was the clearest example of that.

Perhaps White could push up a little higher and overlap a bit more. Perhaps he’s a little tired and Tomiyasu could offer a marginal improvement at the moment. My gut feeling is that the fixes lie elsewhere.

How do you unstick the left?

Any appraisal of the current form of the Arsenal left has to start with a comparison of Eddie Nketiah and Gabriel Jesus. Before Eddie Nketiah’s run of starts, I expressed great optimism while wrapping up with two questions:

First, can the team as a whole work to minimize some of the difference in progression and disruption with Jesus off the pitch? Second, can Nketiah seize the moment, and finish with higher efficiency to offset the quality of Jesus elsewhere?

On the second count, ✅.

On the first count, also ✅—but with many caveats.

An eye test will safely tell you that Eddie has been great. Trust your instincts. He’s been an above-average Premier League striker while doing the most important thing: scoring 0.6 goals per 90. He was pivotal against Manchester United.

Lower blocks haven’t phased him: he turned in a strong performance against Tottenham in a 2-0 win, and his mature hold-up play helped convince Newcastle to stop attacking, forget they’re a third place team now, and go for the Full Dyche.

So any comparison to Jesus is no knock on him. Jesus has simply been one of the better all-around players in the world:

Despite all of Eddie’s enhancements in middle-third play, he is still constitutionally driven by goals—and is more likely to hang around the net than his teammate. That is as it should be. He’s good at it, they are different players, and those very sensibilities are what won the game against United.

But in terms of overall frequency of impact, we can see how different their games can be when facing comparatively deep blocks:

Against Everton, Nketiah played very centrally, often flanked by both Everton center-backs. He made a lot of dummy runs with varying degrees of believability, but he was ultimately able to generate fewer touches and actions than any other start this season.

Therein lies the central question facing the Arsenal squad as presently constructed. If the striker stays central, and Xhaka stays parked in the left half-space, how exactly is Martinelli supposed to generate danger inside? How do you make sure the attack retains its fundamental unpredictability?

Here are some ideas.

1. Play Martinelli into space

Arsenal has faced many 5-back shapes. While the team has so far been more neutralized when playing against a muscular 4-5-1, there is one area that may be easier to attack in a 4-back.

In transition, teams employing a 4-5-1 like to stay compact to defend the “V” of the goal. Without true wing-backs, that opens the opportunity to play wingers into space.

Carrying the ball forward with minimal obstruction, here’s an opportunity that Partey passed up 13 minutes into the game. Martinelli had a sprinting start on a flat-footed 34-year-old:

There’s a lot of talk about Martinelli’s form, but we’re only a few games removed from Ødegaard delivering him a through-ball on a platter against Brighton, and Martinelli beating a young burner (Lamptey) for the goal. As much as the team likes to keep the ball on the ground and retain possession, let’s get the dude in space.

In addition, hitting on a few of these will force the defenders to play against type, and be less comfortable about simply dropping back and giving the likes of Partey and Zinchenko space to roam. If they can get more attention pulled up towards them, that means more space behind.

2. Put dribblers in the left-8

If games like Tottenham, Liverpool, and United are a showcase of Xhaka’s strengths, more bogged down affairs like Newcastle and Everton tend to shine a light on some of his limitations. It was the case on Saturday, particularly on rewatch.

At 12’, Partey was able to generate the exact kind of situation you hope for against a disciplined block. By attracting two midfielders via dribble, then evading them, he passed the ball off to Xhaka — and now there was a rare chance to face an out-of-shape block, including the option to hit a cutting Martinelli in a golden zone:

Instead, he took another touch, and kicked it out of bounds.

Next is another tough one. At 23’, Zinchenko delivers the ball to Xhaka in the half-space as the defenders aren’t set yet.

But here’s an example of how a lack of dribbling threat can make passing more difficult. Because he’s not attracting direct commitments here, the defenders are dropping to crowd lanes. (Contrast this to how Trossard helped win the game against United by drawing three on the dribble.) Xhaka plays it into traffic and the attack fizzles:

Earlier, at 5’, White had changed the play, first to Zinchenko and then to Xhaka. This wasn’t some big mistake: he simply dinked it out to Martinelli, who miscontrolled it to made the attack go poof. Still, I can’t help but notice that big patch of grass, and wonder what may have happened with a dribbler who was confident they could beat Coady on the turn:

Finally, at 81’, he received the ball with an ultra-high-quality opportunity. Eddie and Trossard were cutting, and no one was fully rushing to meet Xhaka directly. But instead of dribbling forward to pull space for others, or playing a throughball to Eddie, he immediately dinked it out to Trossard, whose defender easily recovered. Trossard fired wide.

Now we enter the #TakeZone. My belief is that Xhaka should start almost every game. However, if the following conditions are met…

The opponent is playing a packed block (so Arsenal’s lineup should be heavy with individual dynamism and dribblers)

Saliba/Gabriel have the opponent attack largely covered (so Xhaka’s efforts as a structural, communicative, Arsenal-third defender are less required)

Jesus is not playing (so the left-8 needs to be a driving force in rotations)

…I believe Arteta should be more aggressive about plugging other options in.

I’ve written at length of Xhaka’s success in his new role, and I expect it to continue. What’s clear is that the role itself is a fucking demon. With two wingers getting doubled, Ødegaard getting coverage, strikers making runs, and Zinchenko dragging people every which way, there are so many opportunities presented in this location. Now that the team is blessed with a little bit more depth, I’d humbly suggest that this intervening period—with lesser teams stacking the box, and Jesus out—is a good opportunity to try some things out.

Ultimately, you want to force the opponent into bad choices, and teams are finding the decision between letting Xhaka dribble and tracking a Martinelli cut to be too easy to make.

My preference would have been for Vieira to come on for Xhaka instead of Ødegaard, who was really coming into the game. I’m anxious to see Trossard in the spot, as I argued here. One needn’t squint too hard to see how Trossard/Martinelli sprinting together at defenders may unsettle them.

I’m OK with the talk of a late-Tierney sub to offer overlaps, and suggestions of Zinchenko offering cover in the left-8. Generally speaking, though, I’m partial to Zinchenko retaining his unicorn status at left-back, where his current role helps him dominate touches and dictate play like only he can. He can overlap, too.

3. Go for numerical advantage through Ødegaard or Gabriel

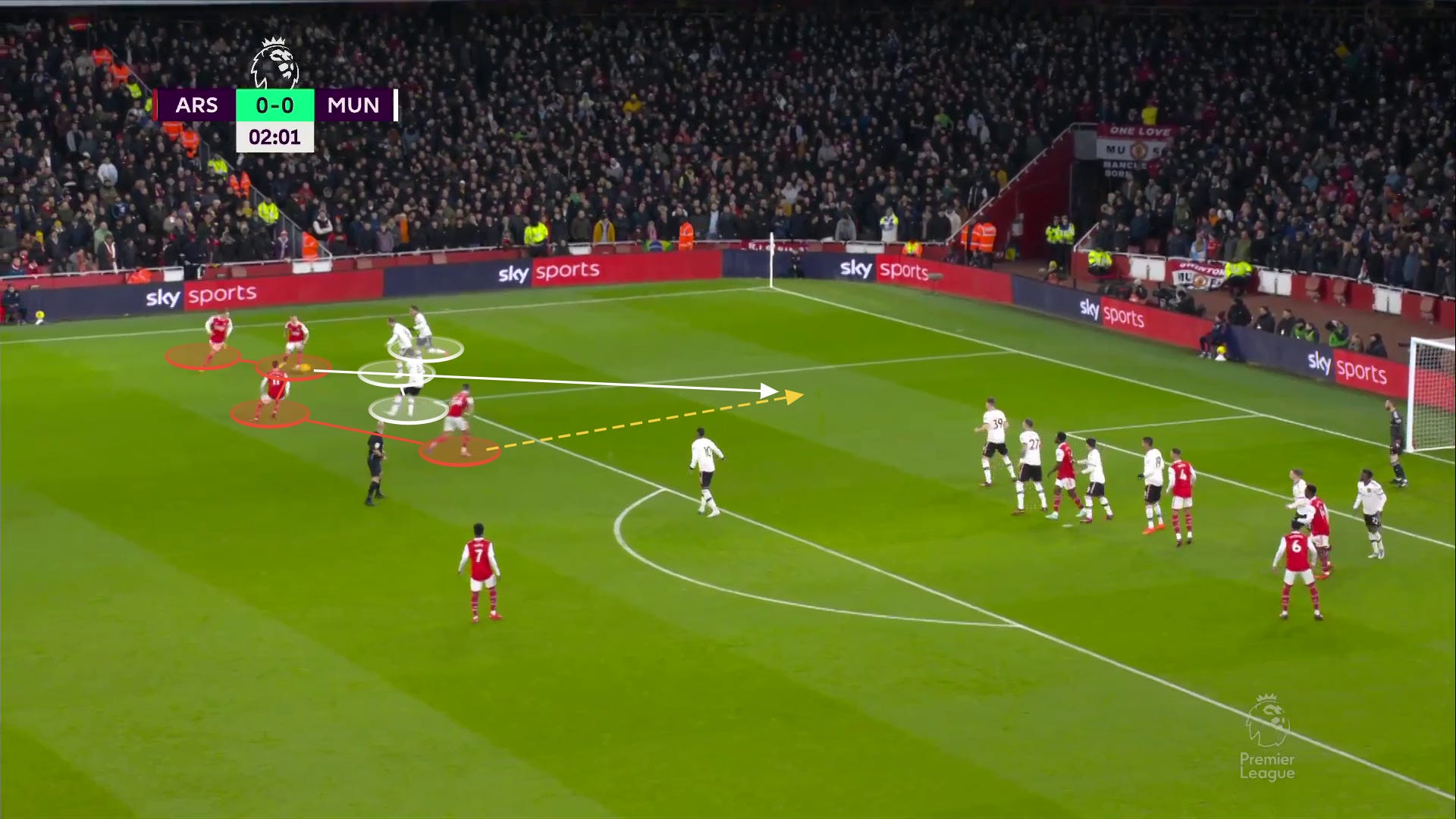

I was a little hard on Xhaka up above, so let me make up for it. When the team is able to generate numerical advantages on the left side, he has a genius for identifying the perfect moment for a cut — as he did against United:

Much of the danger against United was generated in these post-corner sequences where Ødegaard and others were joining the left to outnumber the opponent. I would have liked to have seen that more against Everton.

Likewise, Gabriel cheated up to fully join the wide areas as a wide midfielder, providing “double width”—but it was also too rare a sight. Simply by forcing the wide midfielder/winger (in this case, Iwobi) to lean towards him, you effectively take a wide double-team out of the equation:

As Xhaka stays in the role—and make no mistake, he will stay in the role—the team should continue to look for more routine ways of generating numbers out here, which he is masterful at exploiting.

Especially against teams like Everton, Gabriel can push forward. In the back, Saliba’s got that shit covered.

4. Swing Eddie out wide

While Nketiah stayed pretty central in a performance that resembled a few Haaland games of late, it’s telling that he generated one of the best opportunities of the game during one of the only times he busted out left:

I’ve noticed a lot of rotations are kicked off by the 9 dropping deep, and others swinging around to cover. Against a team like Everton who allows easy progression, dropping deep isn’t necessary—so there have to be other triggers for rotations.

A little more, please.

5. Is this a safe space for bad ideas?

I’ll start with what you already know: in many of the prevailing shapes of the day, the full-backs are providing the width. They do this through overlaps and crosses, while the winger “inverts” to more central positions, shooting with their inside (dominant) foot. See a classic Liverpool example on the left:

This changes with inverted full-backs. With the inside channels occupied by the 8’s, and the full-backs tucking into the midfield, the wingers often are the ones holding the width.

Perhaps after this year’s role updates, it’s marginally less important that their dominant foot is on the inside, as they can play a more traditional winger role if they choose.

When attacks are stagnating, why not flip Saka and Martinelli at times? I wouldn’t mind seeing them try and blow past full-backs using a more shielded body position—similar to the Manchester City pairing of Sané and Sterling a few years back—and bang in some endline passes with their better foot.

I told you it was a bad idea.

What does it look like when it goes well?

It’s important to remember that these blocks are now a weekly occurrence, and generally speaking—brb, checking the table—Arsenal hasn’t had much trouble breaking them down. After City, they face the second-highest PPDA (at 15.14), which correlates to a lower-intensity press, and they’ve, uh, scored a lot of goals.

Let’s use the Wolves game before the break to remember how.

After some frustrating moments breaking down the block in the first half, they won 2-0. How? Fluidity and unpredictability.

Goal 1 was after Martinelli took a dribble all the way across the pitch to the right wing, then switched play back to Jesus on the left-wing, and everybody cut and overlapped from there. Vieira made the “Xhaka cut” and passed it to a crashing Ødegaard for the goal:

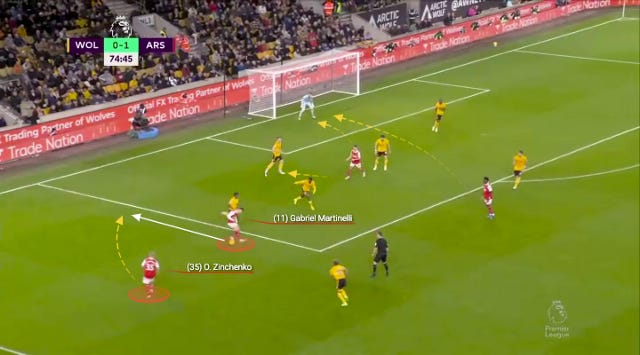

For Goal 2, Martinelli had sprinted from the corner flag after securing the ball, and back-heeled it to an overlapping Zinchenko, which kicked off more box crashing. Look where Saka is:

To regain its form against these blocks, the team must do more weird shit.

🔥 TL;DR 🔥

There was a confluence of factors that contributed to the Arsenal defeat. I won’t be able to list them all, but here’s a start.

The Dyche gameplan was indeed ruthlessly effective, but more than that, he inherited a midfield that was purpose-built to execute upon it. The Everton players never grew tired or impatient, and other teams may have trouble replicating their strategy without the corresponding size or athleticism.

The touch of a few Arsenal players was simply off. Because of the packed box, Arsenal players weren’t able to generate short opportunities: in one of those made-for-broadcast statistics, they’re 16-0-0 across the Premier and Europa Leagues when their average shot is under 17 yards, and 5-2-3 when their average shot is longer than that. Arsenal missed some chances. Corner delivery was subpar, in a recurring theme over the last couple months. They conceded too many corners, and Ødegaard couldn’t maintain balance against Tarkowski.

Lingering questions are more readily answered on the right. A double-team on a winger is not a problem in itself: that means that a single player is dragging multiple players to open up space for others. It’s a question of others making them pay when it happens, and Saka was still plenty effective overall. With White not as flawless as he was pre-World Cup, perhaps he should be ceding more minutes to Tomiyasu, but the gains are likely to be marginal, and the tactics look sound.

On the left, some rejuvenation may be in order. This side is undoubtedly most exciting and effective when it is overloading the opponent’s senses with constant, fluid rotations. There are a few ways of rebooting that dynamism before the resurrection of Jesus, including forcing Eddie out wide; sending Odegaard and/or Gabriel on freelancing expeditions to get numbers; or being more liberal about changing personnel in the left-8.

Arsenal fans should be grateful that Arteta possesses many of Pep’s finest qualities, without the more advanced symptoms of Galaxy Brain. His decision to start Tomiyasu against Salah was a masterstroke, but the one time he embraced his inner Chaos Merchant—triple-subbing off his LB, DM, and 8 for three attackers (Nketiah, Vieira, ESR) immediately after going down a goal against United—well, we don’t talk about that.

In general, he has opted for a steady 11 in the league, and the proof is in the pudding (in this analogy, the pudding is the league table). He’s got more quality depth at his disposal these days, though. The next time they face a team looking to replicate the Dyche/Howe strategy, it may be time for a few small tweaks.

Happy grilling everyone.

🔥