Magic

How Arsenal vanquished a worthy foe; what hard-won tactical lessons were learned; a four-year contract for the four-role White; an øde to Ødegaard; the pushing CBs; the difference Raya brings; more

When asked how he felt after the exultant Porto win, Mikel Arteta started with a word: “Magic.”

And any good trick requires preparation.

“We prepare everything,” said Arteta. “The extra-time, the scenarios, the changes, how the players have to drink and eat and all that and in the end, you have to do it in the game, and to replicate the scenarios is really difficult. Total credit to the boys, stepping up with maturity, with that confidence and they delivered.”

It has been a beautiful week, and we’ll have ample time to think about what’s to come.

A multi-week lull in the schedule will be followed by its equal and opposite reaction before we know it. By the end of the month, a positively relentless schedule kicks off with a trip to the Etihad. Bayern looms.

For now, though, let’s reflect on what we’ve learned.

Here’s a huge feast.

🙌 How the tie was won

One of the satisfying parts of winning is that you get to be gracious in the end.

Great match, you say. You really made it hard for us.

Whenever I’ve been on the receiving end of such praise, it always comes off a little condescending, however true it may be.

I now get to do it with Sérgio Conceição.

Only a few days after facing Thomas Frank, who can nail the little details of a gameplan like few others, Arsenal had their sequel with Conceição. It’s hard to imagine the Porto manager doing much better. This is especially true when considering the skill and investment gaps between the two teams. Every little thing — from certain set piece movements, to throw-in defending, to passing patterns, to whatever else you can think of — had to be meticulously planned and drilled into his players if they were to have a chance. He rose to the challenge. (With the exception of the penalty prep, perhaps.)

In a change from last time, Arteta brought on the double-pivot midfield of Jorginho and Rice that we’d been requesting for the first leg. Havertz went up to the #9, Trossard spelled Martinelli on the wing, and Ødegaard played the lower-touch, higher role we’ve seen so often over the years.

For Porto, we saw the return of the much-reviled mid-block, which we’ve covered in great depth. There were some tweaks, but the broad-strokes remained the same. They stayed disciplined. They stayed close. They stayed frustrating.

There were a few counter-measures for Arsenal’s new lineup. Instead of being so tight and primarily zonal, Porto became a little more man-oriented.

Pepê (the attacking one, not the one who sold his soul for a map to the fountain of youth) followed Rice around at the 8, which is a nice sign of the respect he’s paid at that position. Alan Varela stayed close on Jorginho. And Nico did his best to cut off all service to Ødegaard. They all performed their duties well.

They continued fouling, going down, and interrupting play, of course — as an underdog will. For perspective, the most fouls whistled against Arsenal this year was Porto away (22), and the second-most fouls whistled against Arsenal was Porto at home (18). My problem is less with a team doing that in a knockout tie, insomuch as the time added (or lack thereof) by the refereeing crew, which creates an incentive system for such interruptions. One minute! One minute?! Positively silly.

With the new lineup, and a 1-0 deficit to overcome, Arsenal played a little differently than last time — pushing forward with more impatience and directness.

They took risks. There are game-length effects here, but to boot:

Arsenal had 83 high losses, compared to 36 last time.

Arsenal had 6 deep completed crosses, compared to 1 last time.

Arsenal had 13 deep completed passes, compared to 1 last time.

Arsenal had fewer back passes, the same amount of lateral passes, but 50 more forward passes (187 to 137).

Arsenal had fewer passes per possession (5.32 to 3.83).

Lest we forget the foundation of this game: Porto limited Arsenal to zero shots on target last time, and had even less incentive to attack this go-round.

My take? The strategy and lineup were generally right. There were two problems: some of the passes were imprecise (Jorginho didn’t get the ball enough, and looked a little less fresh on a shorter turnaround; I didn’t like some of the deliveries to the wingers, who often received it in static situations on the touchline; and there were more errant passes from the likes of Saliba and Saka, despite the overall level of skill and gravity they displayed); and Arsenal just lacked an extra runner (Martinelli couldn’t play, and Arsenal simply don’t have enough of this profile otherwise). The feel of the game improved once Jesus came on, and we should never forget what a healthy Jesus adds to this team.

It was always going to be tough. The team fought with the right energy, but weren’t perfect with their touches against an opponent who made it hard.

The more interesting challenge was in the Porto possession game.

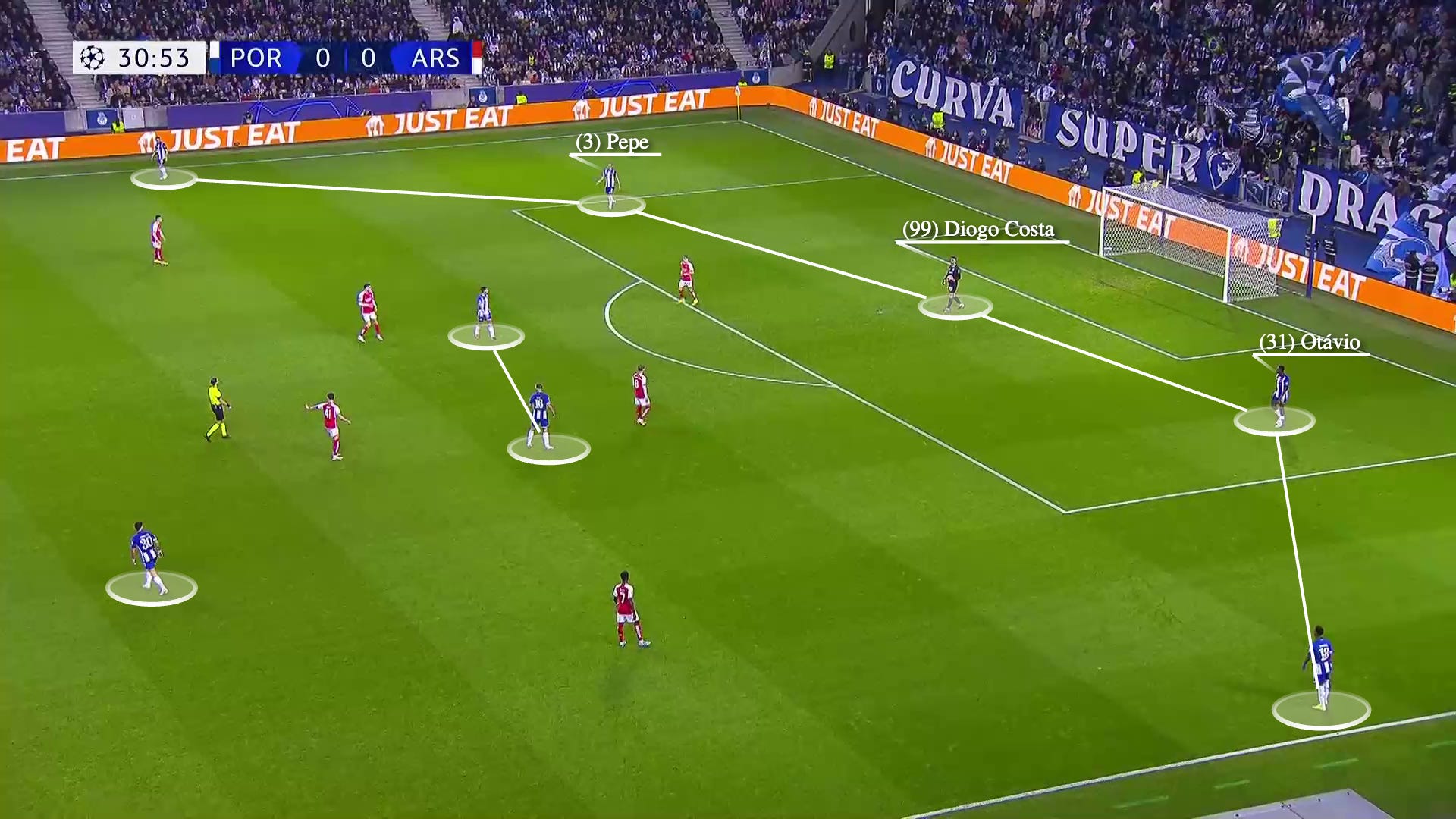

Here’s how they typically line up. The 4-2-4 shape is very en vogue right now, and is often associated with Roberto De Zerbi and Brighton, who didn’t invent it.

This is, generally, what we saw in the first leg. Pay particular attention to the spacing of the CB’s and the FB’s before moving on.

In the second leg, things changed. Here’s what we saw.

You’ll see a dramatic difference in the spacing. The CB’s pushed as far out as possible.

That was noticeable to the naked eye, but the follow-on effect was just as important: the full-backs pushed up high, which dragged both Arsenal wingers (Trossard and Saka) down the pitch.

From there, Porto would ferry play out wide, wait until pressure came, and then blast it long, hoping to find the most isolated attacker (this often meant big attempted switches to Kiwior’s side). Otávio attempted 23 long passes on the day.

This gets to a question I got from Stephen in the chat. I’ll leave in the compliment for my own ego.

Billy, your analysis of Porto proved to be spot on! They were much better than most people seemed to expect. They dealt with everything we threw at them and made life difficult for us in ways no one else has this season. I’m thrilled we won but feel like last night’s match has left me with more questions than answers. How is a team so well-drilled & well-coached only in 3rd in their league? Why don’t more teams play the way they do? What elements of Porto’s performance are going to be employed against us by other teams during the run-in? Should I be worried? Because I am! 😬

Let’s investigate.

Below is a rough approximation of how Porto did build-up. Costa would handle the ball in the middle, and there was a staggered pivot of midfielders in front of him.

From there, the full-backs pushed high and the CB’s pushed wide. There are a couple requirements to be able to do this: the GK needs to be able to “quarterback” the play by himself, and the CB’s can absolutely, positively not lose the ball — the recovery shape for the build-up team is utter shit, and any dispossession offers the chance of a goal.

But you see Porto’s advantages if Arsenal were to try to press. The “door hinge” front three pressers just have so much space to cover, as you saw in the clip above. Ødegaard, in particular, is overburdened on the right with only Jorginho behind and Saka yanked all the way down. So the smart thing to do is what Arsenal did: relax the first line of engagement, ease the press, and just try to be patient and steal the ball when possible.

This dulls the impact of Arsenal’s best playmaker this side of Ødegaard and Saka: the high press. I’ll say it every week, but in practice, there are no separate “phases” in football. If you take some of the bite out of Arsenal’s press, you have hurt them in attack.

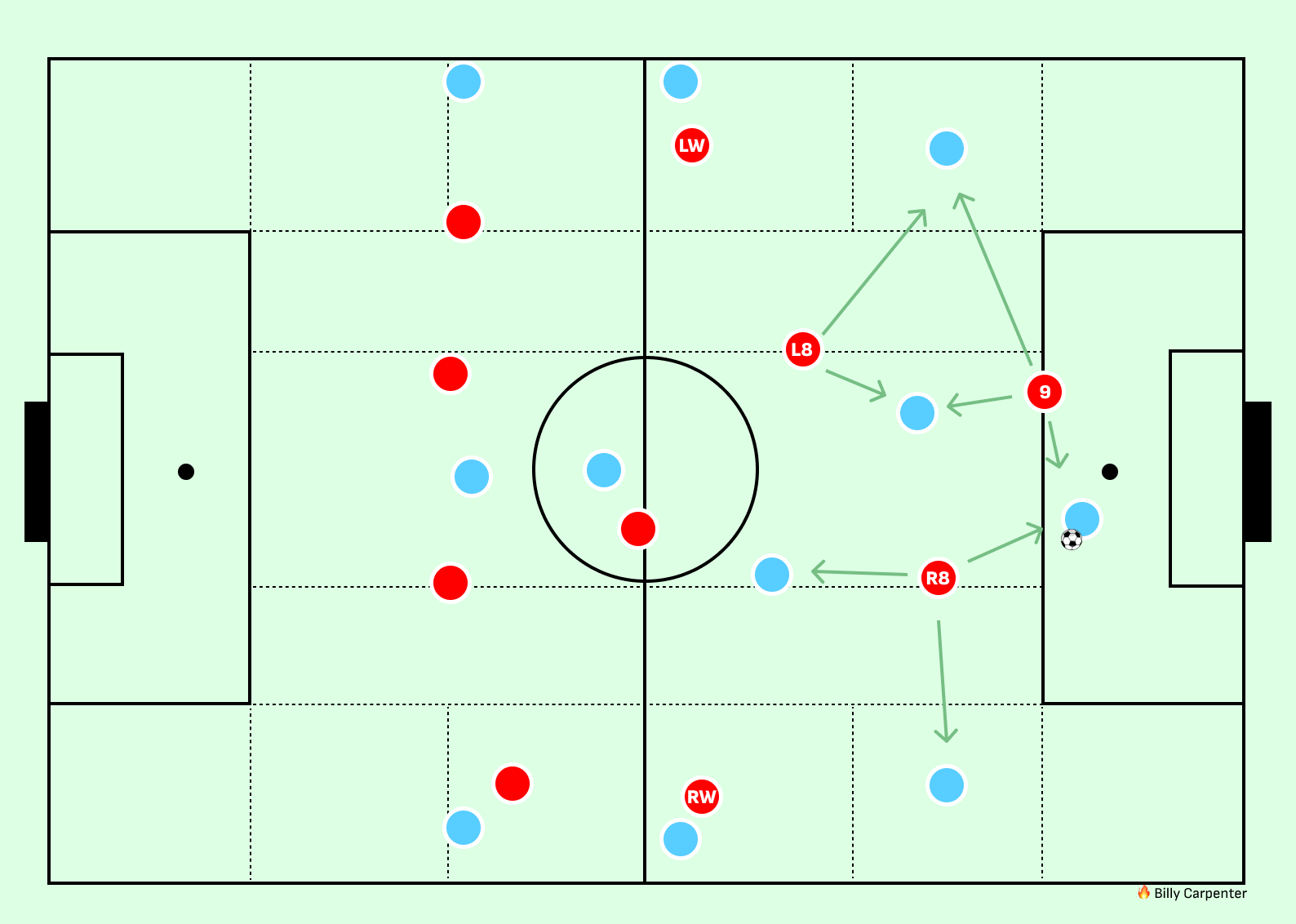

So what would Arteta do if he wanted to dial up the pressure? It may look something like this.

The wingers are higher up and the highest pressers are more supported. You’ll see we’ve had to “borrow” a player from the backline to do this. This can be either of the full-backs (Kiwior or White, in this case), usually the ball-side one, doing aggressive jumps to back up the winger, and, say, Saka having “hybrid” responsibilities out wide on the wing. By pushing the wingers up high, the added pressure up top has a much higher chance of resulting in dispossessions and dangerous opportunities.

But there are big trade-offs. The first is that the backline is purely man-to-man. If any of them have a moment or a bobble, there’s a high chance of concession.

But the more important one is highlighted there in red. If you leave the #6 alone in the middle of the pitch, and don’t have an extra CB there to support him, they are going to have to cover a lot of ground.

I don’t mean to drudge up old trauma, but it can look a little something like this.

So there would be a straightforward counterargument to pressing too aggressively against this shape: you have a huge risk of putting Jorginho into space.

After Arsenal lost the ball here, you can see the danger of having a slow midfielder patrol big spaces here.

So it’s important to keep things in proportion. Was Arsenal’s press at its most ferocious? No. The first line was generally pretty relaxed, and Porto had a little more possession than they may usually enjoy.

That said, the highest pressers, particularly Ødegaard, ran tirelessly anyway, and picked their moments to nick the ball. There were real chances created.

So what’s my TL;DR on this whole shebang?

Arsenal did the right thing in not pushing another player up and risking putting Jorginho in space or isolating the backline 1v1. It was, after all, a clean sheet.

Not every team can do what Porto did here. It requires a really smart, capable GK and CB’s who never lose the ball. Otávio is a really nice talent but it still got pretty close to misery for him.

This is a good display of the out-of-possession considerations to be made when formulating a lineup. You are essentially trading Jorginho’s passing for a little less flexibility out-of-possession (which I thought was a good trade). If you start Rice at #6 and Havertz at #8, and have Rice through the middle, you can probably afford to press with another player; this may lead to more chances in attack.

It may have been worth switching the positions of Rice and Jorginho here, as we saw against Liverpool.

If you put a better athlete in the #6 here, the whole calculation may change. This is why my sicko side will never fully discount the abject fun and admonishable bullying that somebody like Amadou Onana could offer, even if I have some other questions.

To answer the other part of Stephen’s question — how is a team so well-drilled and disciplined only third in Portugal? — well, they’ve been figuring out some things of their own. A side like them is generally lab-created to be hardest on top clubs; otherwise, they’ve largely evolved from the double-striker formation that they’d usually be identified with, and Otávio (the LCB) joined up in January, adding something much-needed to their overall structure. In their last four league matches, the cumulative score was 14-2.

But enough about them.

💥 White Noise

It’s been an eventful couple of weeks for Ben White. I hereby rise to defend him.

Back in October, the Tanned White gave a wide-reaching interview with Sky Sports in which he talked about the responsibilities of playing his newer role under Arteta.

“To play full-back for him, you've got to be a centre mid, a centre-back, a winger, a No 10. So, it's been about developing the whole of my game, rather than just as a full-back or a centre-back.”

It has never been more true than the last month or so. I think we all intellectually know how flexible he’s been, but it’s another thing to pause and actually reflect upon it. Let’s count the ways.

He’s always comfortable as a CB in the back-three of build-up. Against Newcastle, he was interchanging a little with Saliba, giving the latter more freedom to push up and join the midfield as needed. Raya plays a role too, of course.

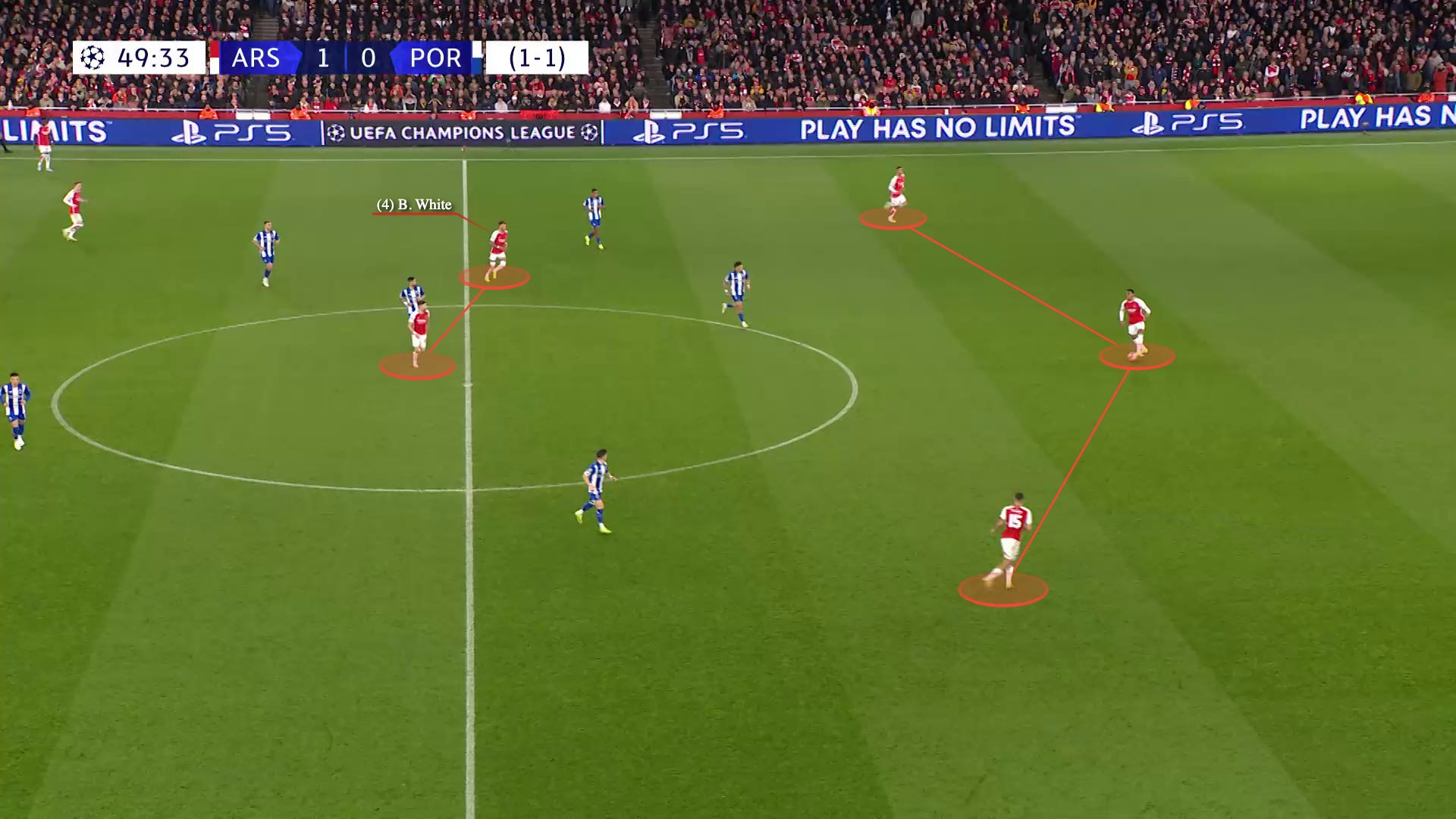

Since the West Ham game, White has been tucking in as a primary or “auxiliary pivot,” joining up the midfield to help progress play.

When he arrives from midfield, he can show up in the final third by tucking right into the half-space, as he often did last year. Here, he exploited the gravity of Saka — who immediately commands a double-team — to deliver an assist from this zone.

But it gets more freewheeling than that.

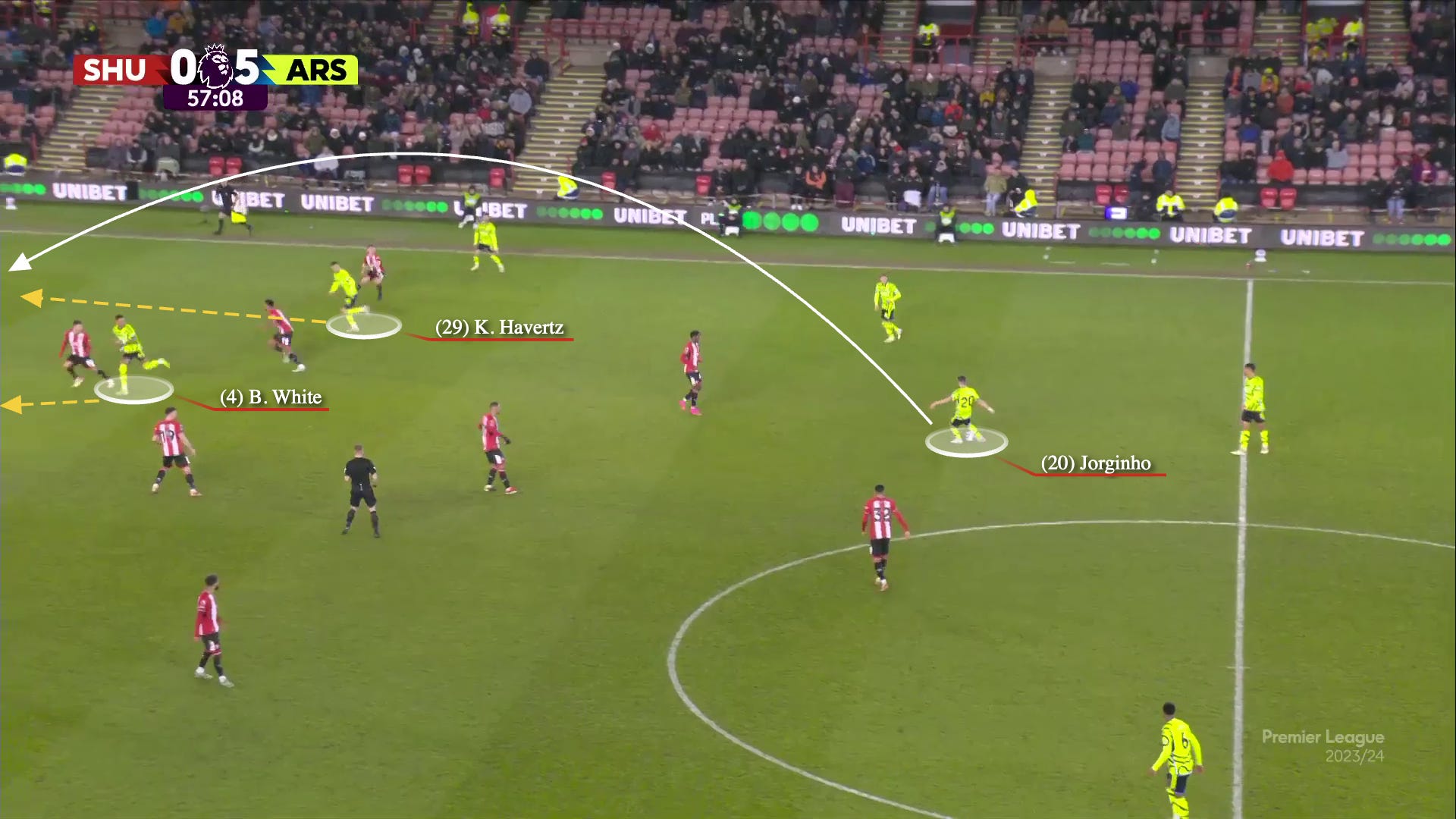

Nursing a 5-0 lead against Sheffield United, Jorginho and Ødegaard had dropped back in the formation, so White went storming through the right half-space, actually getting inside of the striker at the time. While the rest of the game had (understandably) slowed down a little by this point, Havertz and White were still running.

After Havertz came down with it, White was in a prime spot to blast home a spinning, wild, no-look, weak-foot goal into the side netting.

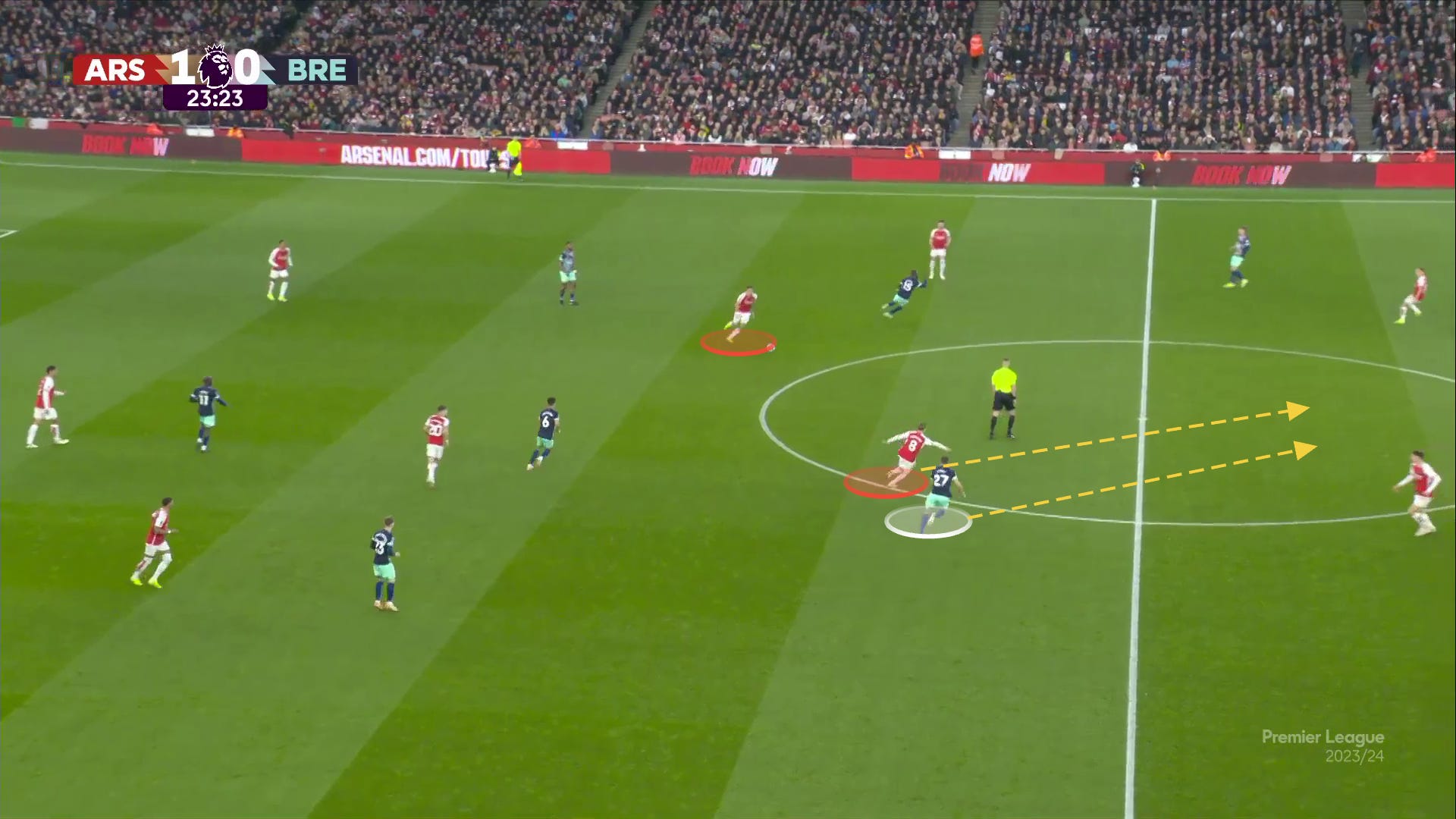

But the most meaningful moment was when it was 1-1 against Brentford. As the team pushed forward, the attack risked getting a little staid — you can see how many Brentford players are in the box after a dead ball.

But White just kept jockeying, moving, pushing things forward. And this is an important shape in the context of Arsenal’s season: Ødegaard dropping lower, White high, Saka in the half-space. You’ll see Havertz and Jesus “switched” as the 9 and the left-8:

…and from there, we have the winner.

One of the real improvements in the attacking dynamics over the last couple of months is the increasing use of the shape you just saw, and which I’ll outline below. White is out wide with Ødegaard lower and Saka pushed in. There are plenty of subtle schematic reasons this is effective, but I’ll choose the easier ones: more players have access to the team’s best player (Saka), and that player is closer to goal. White’s comfort out wide has played a big role in that.

…and I’d be remiss not to mention how good he’s been at stepping up on transition balls and keeping things pinned.

Against Porto, White had the second-most touches on the team (behind Saliba), and led the team in both blocks (3) and interceptions (4).

His role is incredibly intensive, both physically and mentally. Late in the calendar year, it became pretty clear he was playing through something. It’s no surprise to hear reports that he is “known to mask injuries in training so he can play at the weekend,” which probably isn’t ideal, but fits with an overall picture.

I feel compelled to mention that he started this season essentially starting in place of Gabriel, with Saliba pushed over to LCB. And guess what? He was still doing overlaps.

I’m hesitant to wade into the Southgate drama except to say that White does not seem to suffer fools gladly, and has the ability to say “that does not sound like fun, so I am not doing it, regardless of what somebody else expects,” which are two qualities I am frankly envious of. He’s always seemed to get along swimmingly with the likes of Bielsa, Potter, and Arteta — so my tea-leaf impression would be that there is a, uh, variable here.

Ultimately, I don’t know everything that happened behind closed doors. But I wasn’t surprised to see this in the Athletic story:

At one team meeting, Steve Holland, England’s assistant manager, is understood to have made a comment in front of the other players and staff about White’s admission in an interview that the player did not like football.

We’ve all been in the workplace with the person who runs laps around everybody else in productivity and leaves at 5 every day; we’ve also been around the person who performatively stays late every night, showing their dedication to the craft, while breaking shit left and right, leaving a mess for the others. People have different ways of approaching problems; all you can really evaluate is the work itself. Good managers can discern all that.

I look at what White can do — as a CB, as an overlapping CB, as a right-back, as a midfielder, as a 10, as a winger — and I see somebody who likes playing football an awful lot, and has put a ridiculous amount of dedication into learning the details of his trade.

Long-term contract, well-deserved.

The rest is noise.

🇳🇴 An Øde to Ødegaard

We went through some of the tactical complexities against Porto. I exhausted my sober analysis. So, like we did with White, let’s continue the hagiography.

We’ll start by saluting his partner in crime, which will also call attention to an under-celebrated part of the captain’s game: his off-ball work as an attacker.

Brentford set up in a 5-3-2 formation. I remember Frank talking about how he settled on this formation through his travails as a dominant Championship side (with Raya as keeper). He thought this was the toughest shape to play through.

Below, you’ll see how the middle is jam-packed, but there is still appropriate width to defend the wingers. Janelt (the LCM at this time) was to hassle Ødegaard in this phase of progression. Then, when things got more advanced for Arsenal, his job was to double Saka.

After the switch, Lewis-Potter (the left wing-back) is solidly on Saka, and then Janelt commits a clear double-team. This leaves the half-space open.

And there’s the first goal.

The primary thing to watch here is the gravity of Saka. Even if he doesn’t have his best game — he was great here, of course — this is the fundamental advantage of having a superstar like this. The effects compound:

He has a long track record of hurting teams whenever they leave him 1v1; as such, they rush over help, sometimes haphazardly so.

This opens up a soft spot in the half-space and the overlap; we saw the former here.

BUT — this is also an out-of-possession advantage. In this example, a wing-back and a midfielder are dragged to the corner, which dulls their ability to break out on a counter. In many other examples, it’s the opposing winger.

Still, though, the best case is to get Saka isolated, no matter how many obstacles are in the way. Why? Goals.

If he gets a hint of daylight, there’s always a chance.

Let’s look at how to do that.

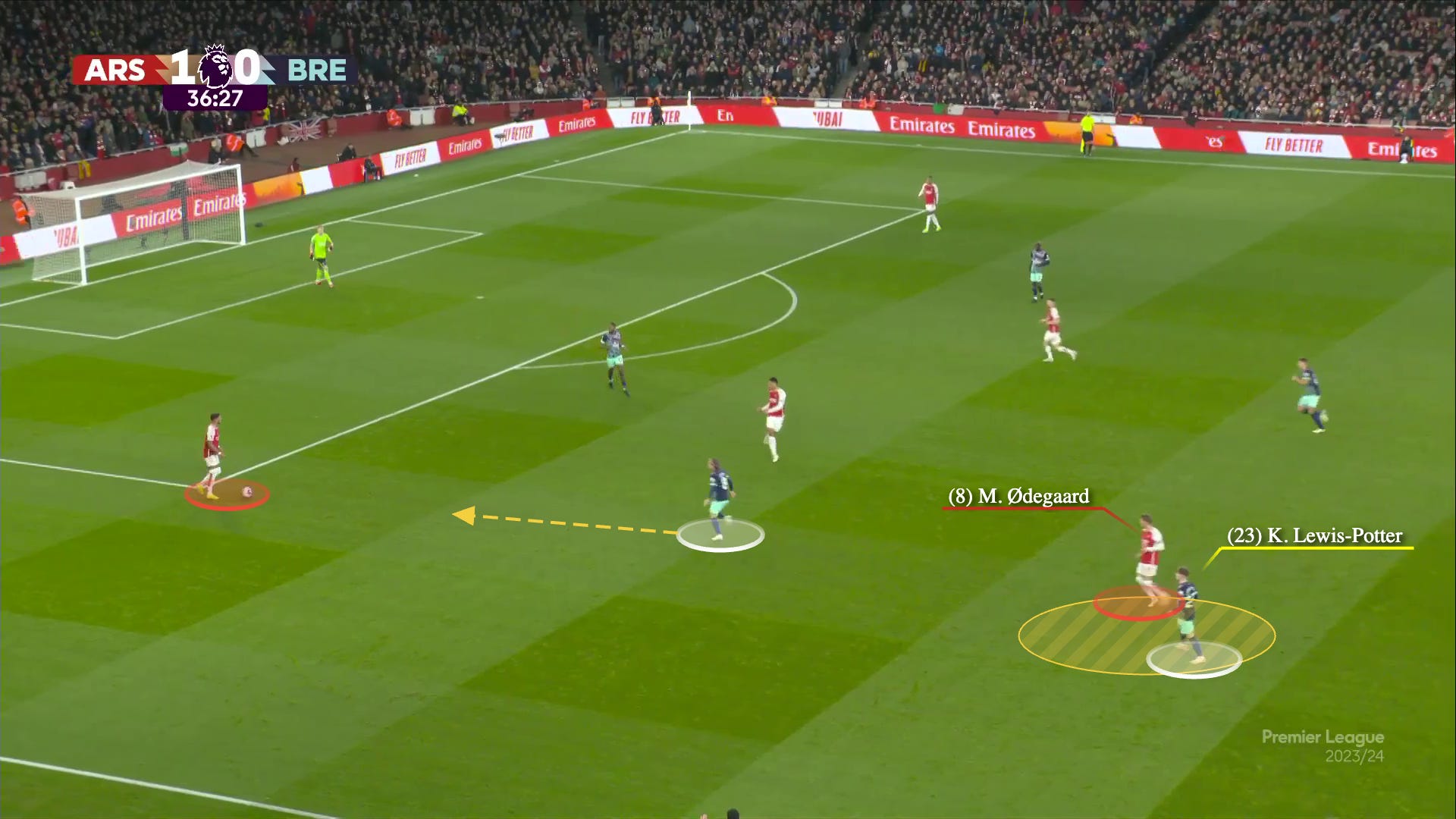

After that first goal, Brentford looked to increase the intensity of the press. Because they had three CBs back at all times, they used their wing-backs and midfielders to back up the initial pressure.

Here, Lewis-Potter runs all the way up to White to press. Janelt is marking Ødegaard during this phase of progression.

Now that White has hit it to Kiwior, Lewis-Potter is sucked up the pitch. Ødegaard makes a really demonstrative run through the middle to drag Janelt in that direction.

The players you saw double-marking Saka in the first play? They’re both trying to catch up to the play, and Saka is lined up against a wide CB.

That one didn’t fully come off, but it was a good situation to manufacture.

Mathias Jensen came on for an injured Christian Nørgaard a little later, and responsibilities shifted.

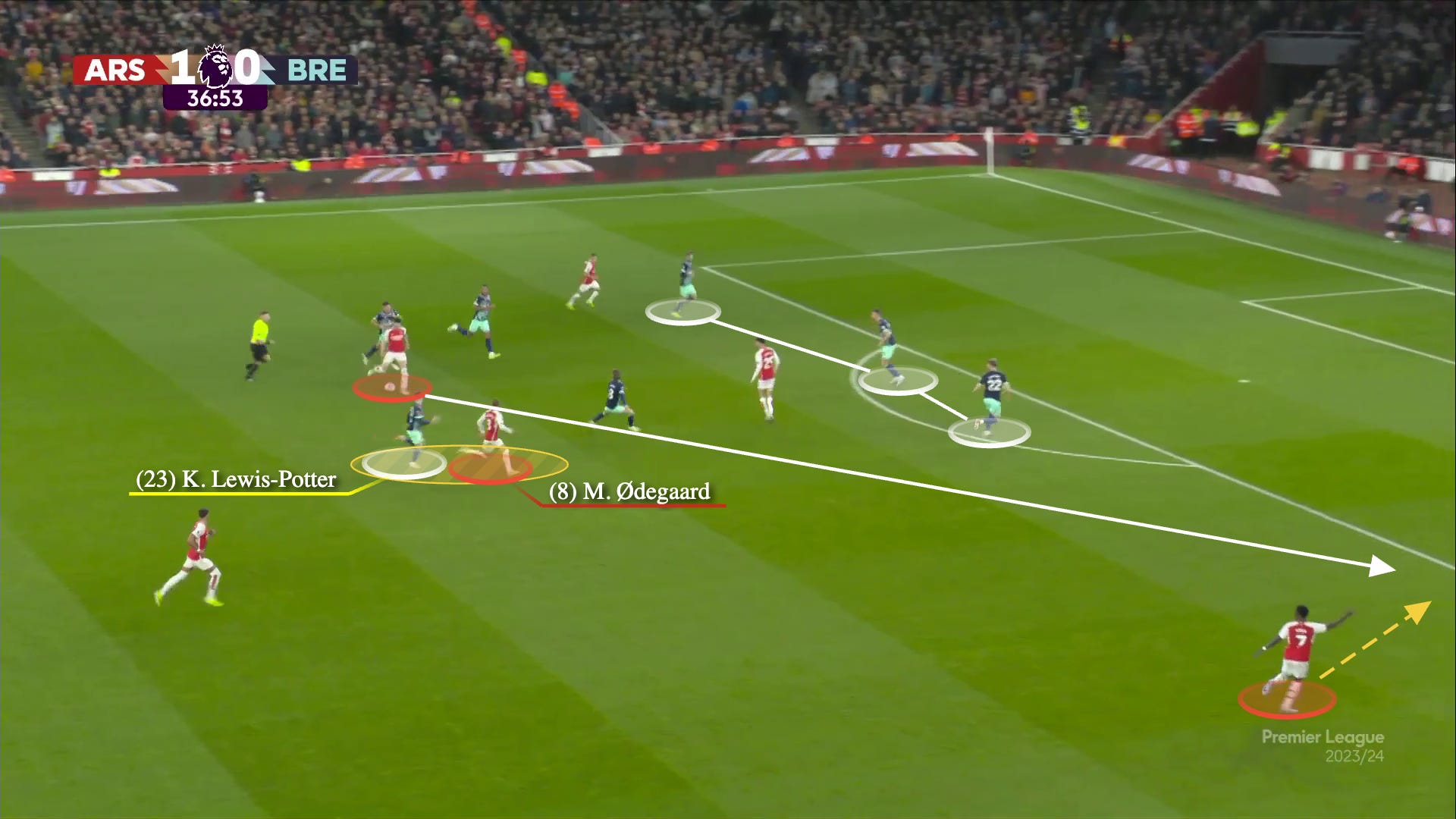

Here’s Jensen running up the pitch to supply pressure, with Lewis-Potter man-marking Ødegaard behind him.

What do you do with a man-marker? You take them where you’d like them to be. In this case, Ødegaard decides to drag him all the way over to the other side of the pitch.

Now, Lewis-Potter, a left-wing back with Saka in the back of his mind, is on the other side of the Arsenal penalty box as Kiwior has it on the touchline. It’s hard to imagine him further from Saka.

There are some quick passing patterns until Ødegaard finds Rice (before he even understands he’s free) and Rice goes sprinting up the line on one of his trademark carries.

And there you have it. The entire Brentford shape is discombobulated, and Saka — the player who they’d really like to double or triple team — is in his own solar system.

Again, that one didn’t fully come off, but I just wanted to call attention to how 1v1s are ultimately created, and how seemingly unrelated off-ball runs can create great situations in the final phase.

Ødegaard’s year, from my perspective, is going underappreciated.

I think most people can appreciate that he’s having a great season, but I’m not sure the level of it is truly settling in with the world writ large.

His assist against Porto was clear for all to see. He came down with a second ball, drifted to the other side, waited until he could bait a 1v4, then passed through it to Trossard. It was sheer will.

It was the quintessential big game performance.

And if you take a step back, the numbers get even more stark. When compared to all players in the “European Top-5 Leagues,” he currently ranks:

#1 in passes into the penalty area (82)

#1 in through-balls (27)

#1 in shot-creating actions via live-ball pass

#3 in progressive passes (behind Xhaka and Rodri, but he’s done it in 1100 fewer passes than those two)

All while captaining and leading perhaps the best press on Earth.

Are discussions about him unnecessarily restrained? You decide.

♦️♦️ Pair of diamonds

I’ve talked about this a bit on Twitter (ugh), but I should probably stop doing that, so I’m going to cross over some of my thoughts here.

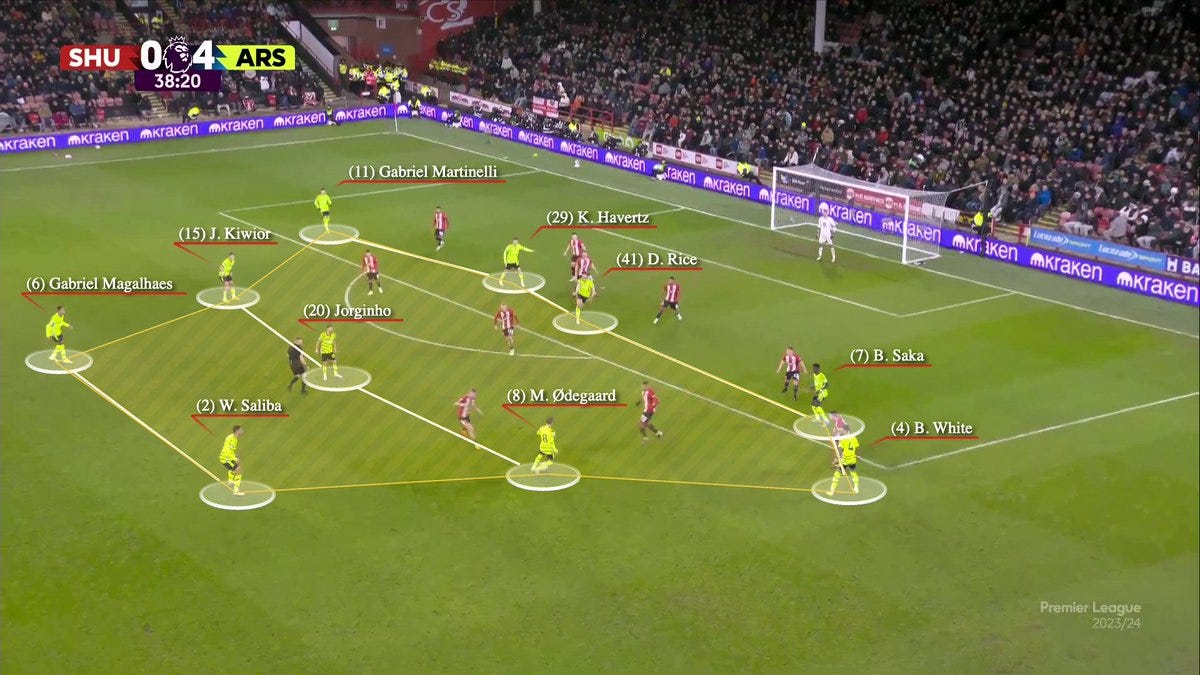

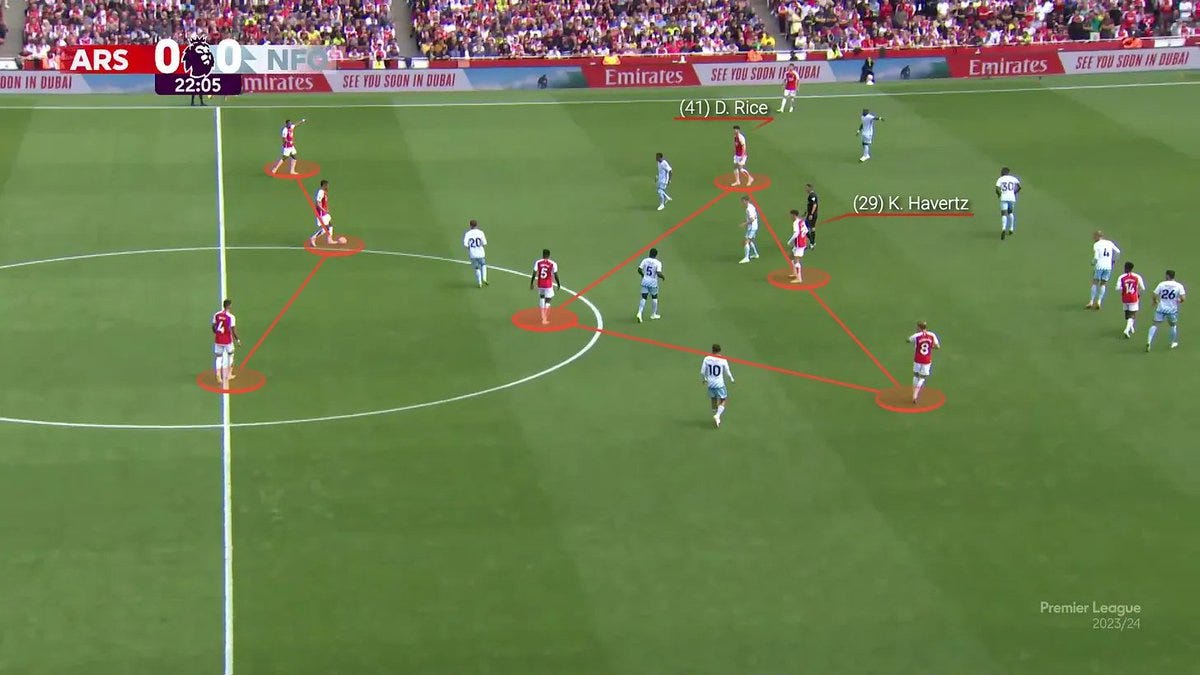

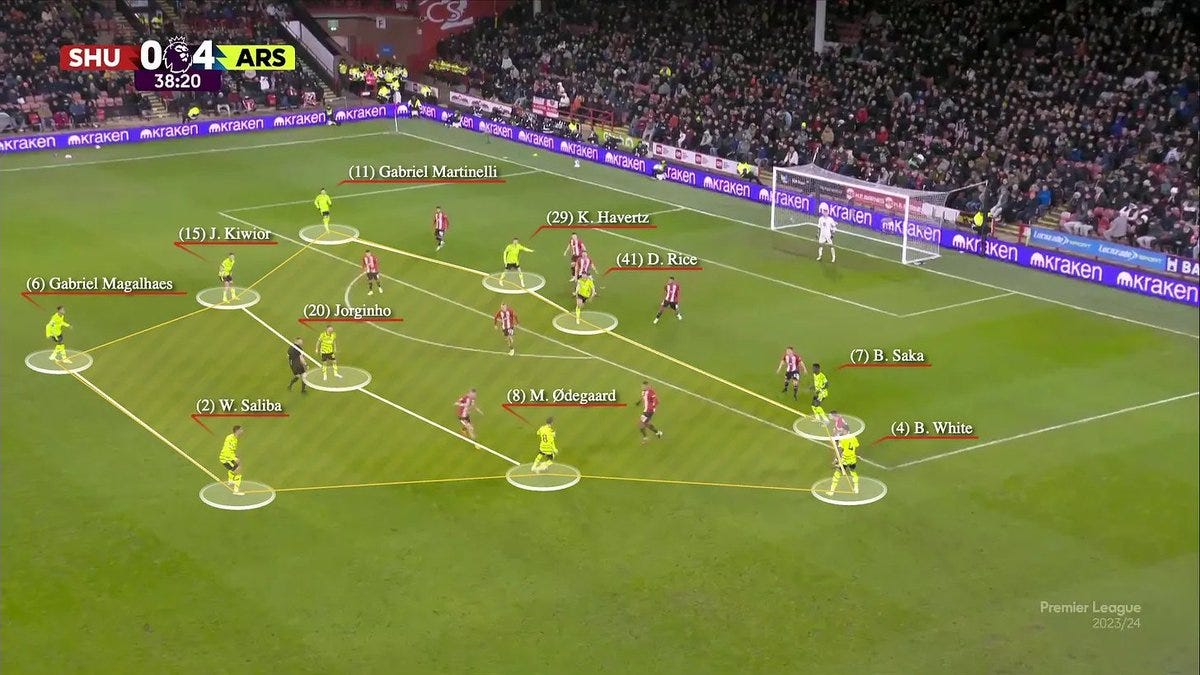

About a week ago, I posted this screenshot of all ten outfield players for Arsenal before the fifth goal. Yo:

You may have the normal questions: How was this achieved? Why didn’t Sheffield United push somebody higher up?

A lot of it has to do with the CB pairing. With that, I wanted to dive into how Arteta has evolved in his deployment of Gabriel and Saliba throughout the season — and how he used them both to create the wide overloads that suffocated Sheffield United and kept them pinned.

While this was an extreme example, Arsenal have been the best team around at dictating the location of battle. From data from markstats, they currently have the highest average defensive actions of any team in the top-5 leagues, and face the lowest opponent defensive actions.

From preseason, Arteta envisioned a Saliba that was even more ball-dominant and central than his previous mint. James McNicholas had a great piece to that end.

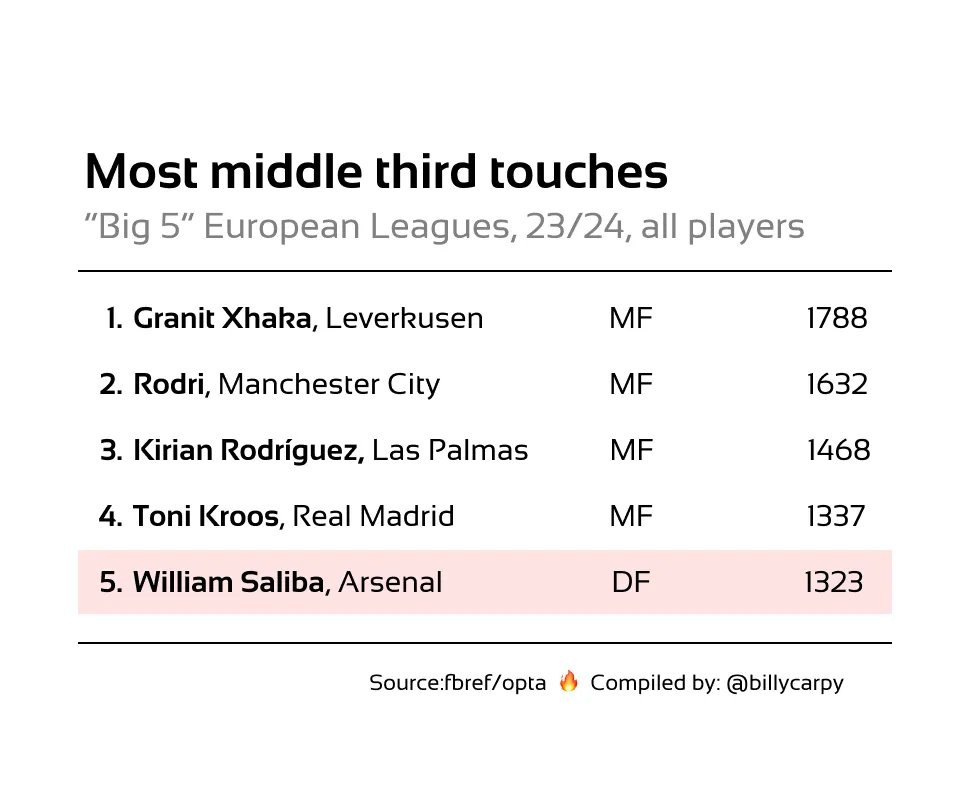

This vision has come to fruition. Saliba has more touches in the middle third than any defender in the top-5 leagues in Europe.

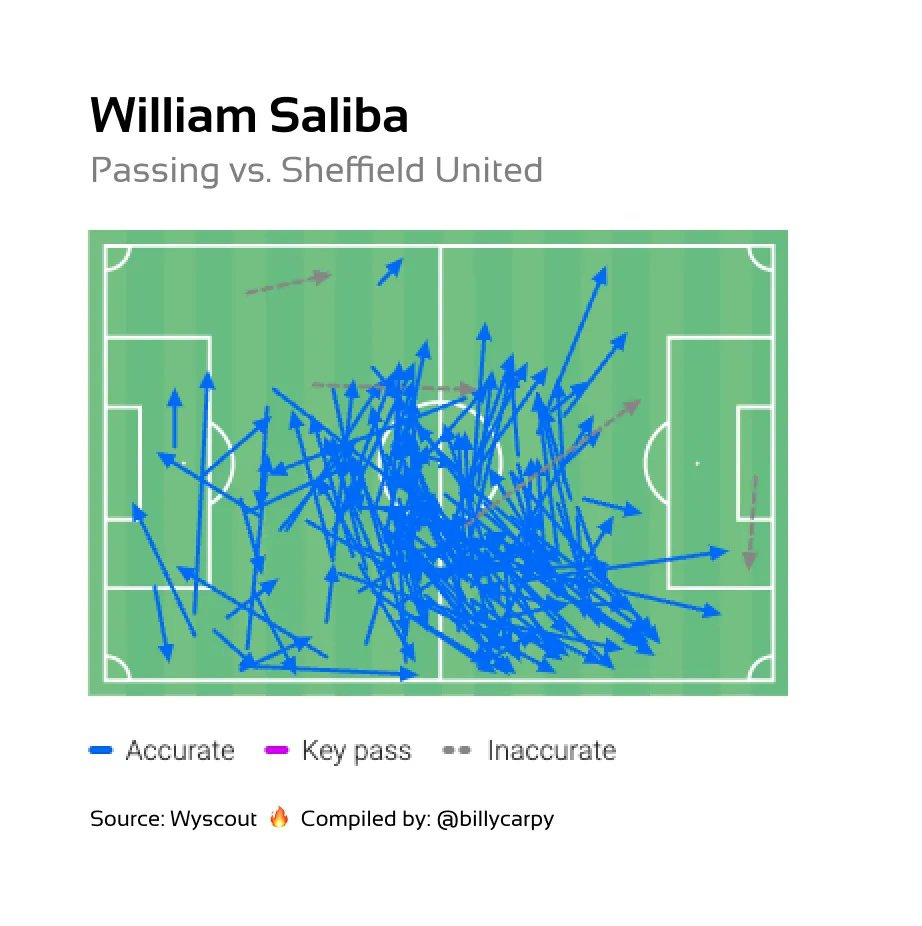

This was especially true against Sheffield United. Saliba’s 168 total passes (per Wyscout) were 41 more than his previous career-high, and more the opponent completed total. He went 83/83 on medium-length passes.

But what was most interesting was his evolving relationship with his batterymate. Against Sheffield United, they combined for 271 touches in the middle and attacking thirds, per fbref/Opta data. In other words, they ran shit.

The dynamics last year were relatively stable — at least when both were healthy. Saliba would man the fort at CCB, and Gabriel would support the left side, where Zinchenko was roaming and needed help. This also allowed Gabriel to be more involved further up the pitch as Saliba swept behind.

All kinds of permutations were tried in the preseason and early going: Timber inverted RB/LB. Timber non-inverted LB. Partey inverted RB. Rice 6+8. Gabriel even was on the bench in the early days.

The only constant was that Saliba was central.

Injuries mounted, and practicality ruled the day. In standard games, the team largely settled back on last year’s dynamics, with the inversion coming from the left side (often Zinchenko), Gabriel floating left and up to help, and Saliba staying back.

Eventually, those dynamics started to falter, and Ødegaard was unleashed deeper and wider to fix everything for a month there. He basically did, scorelines be damned. But it wasn’t fully sustainable in every contest.

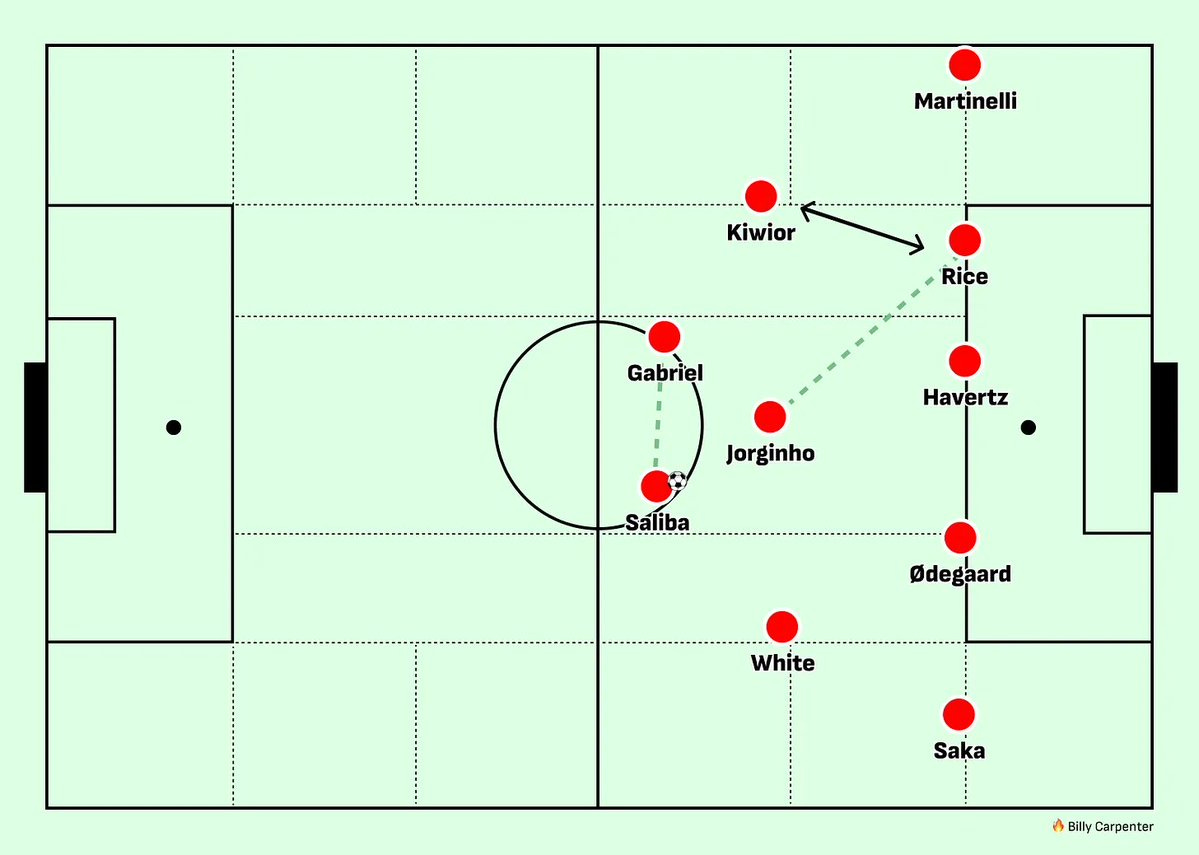

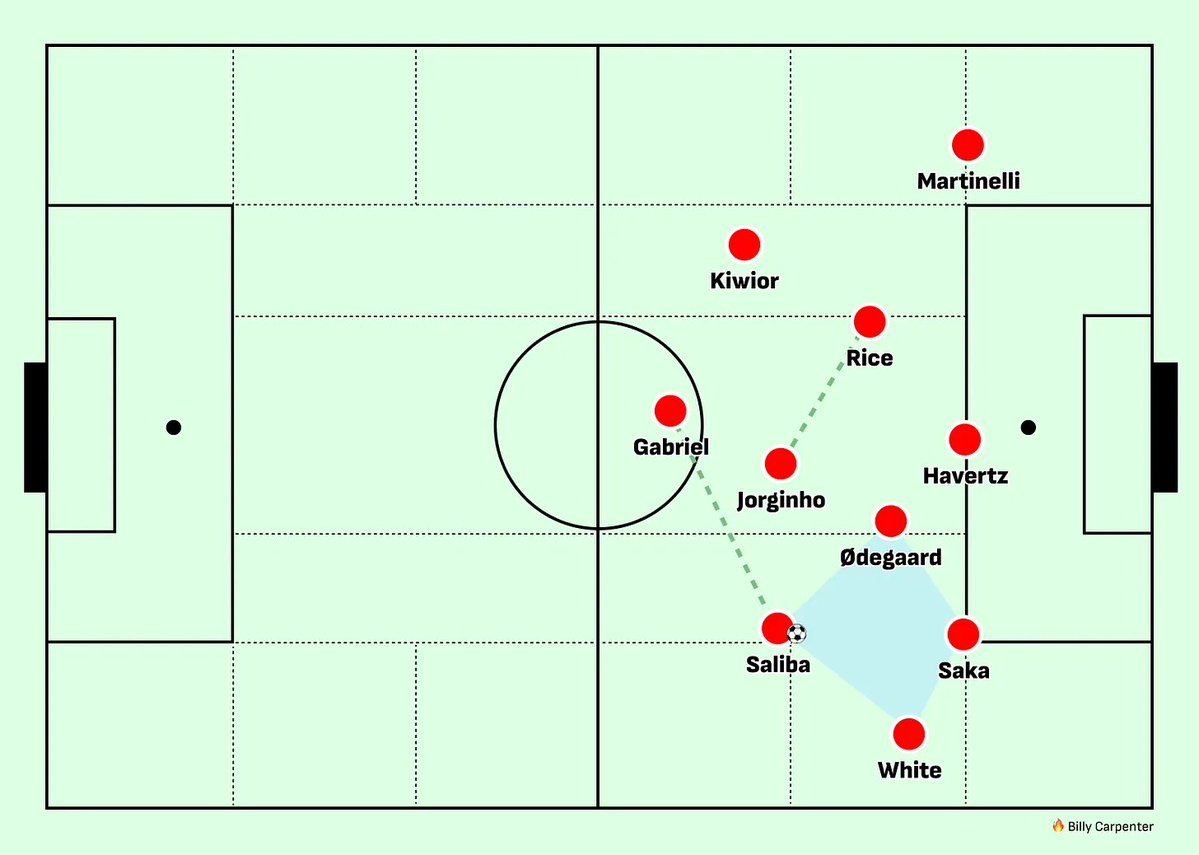

Upon return from Dubai, the team has kept evolving. The big shifts? The increased role of Jorginho in specific matches, as well as the aforementioned pivot I like to call the “White Rice.”

In the latter case, dynamics flip. Gabriel has the deep responsibilities, and Saliba is the one with more freedom to push up.

This has had the practical effect of allowing Saliba to carry it up and participate in more of the reindeer games up front. For those who watched him in France, you’ll know how talented he can be on the carry.

Previous questions about Gabriel having a clumsy streak at CCB haven’t shown up.

So, basically, if it’s a left-inversion game, then Gabriel can push up. If it’s right, then Saliba does.

But what happens if the pivot can be created from either side, and you feel more confident with either at CCB, *and* the GK can play LCB or RCB? We got a taste of that against Newcastle.

We got the full helping at Sheffield United.

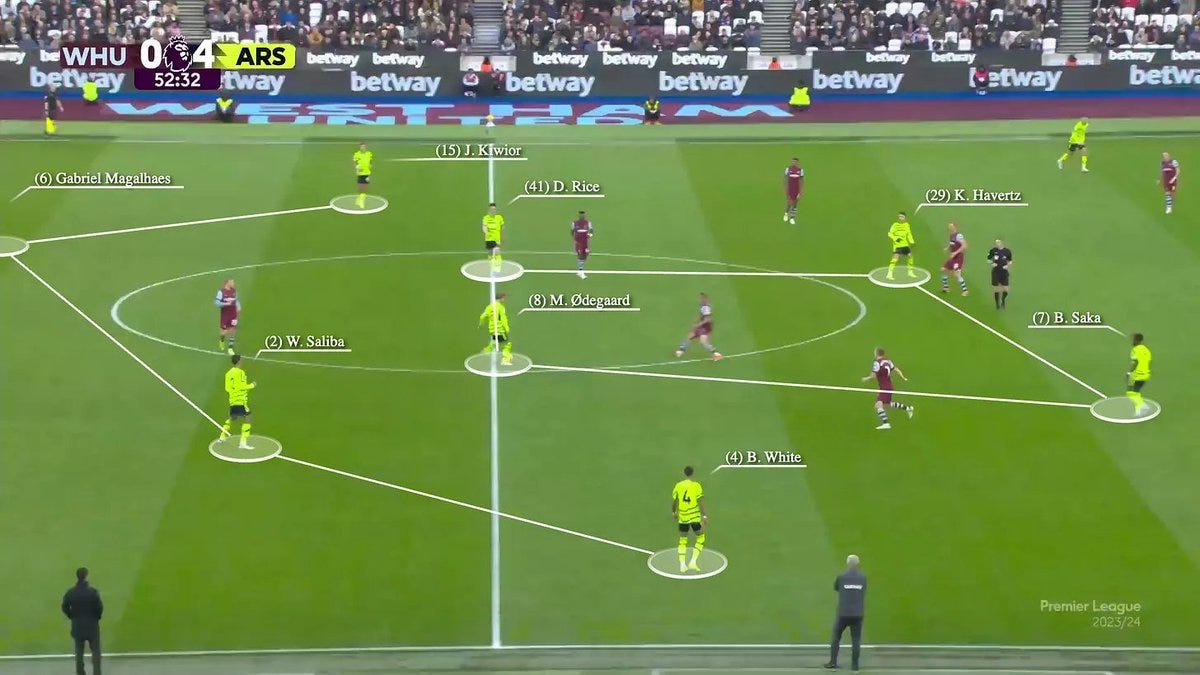

Let’s make it visual. For example, here’s what a later phase of progression could look like if the ball is in the middle in a 2-3-5.

Now, if the ball is played out left, the LCB can push and help create overloads over there, and the auxiliary pivot/CB/FB on the other side (White) can swing back, and a bendy 2-3-5 is maintained. Nothing too new here.

But if the play swings to the other side, the opposite can happen more. Gabriel is trusted at CCB, so the left side’s auxiliary CB (Kiwior) can swing lower, and Rice can also drop as needed (and based on the dynamics).

You now have balance: a CB-created overload on both sides.

OK, Billy, but that looks awfully exposed in back — just one CB. Sheffield United could just place a player higher up and hit on the counter. Right? Right?

They got an immediate example of what would happen if their advanced players didn’t get fully back.

Here, Gabriel and Jorginho have joined the wide diamond. Because McBurnie (the striker) isn’t “in” this, it’s 5v4. Two passes create a 2v1, and Rice is through to the byline.

And there’s the first goal.

But more unique to this one, when Arsenal ferried play the other way, the mirror image would happen immediately. This was a late-game example but it’s the first one I can pull up to demonstrate that moment — look how Gabriel falls back to CCB as Saliba carries forward.

Here’s the clearest example after that first goal went in. Gabriel is central, so Saliba carries up to draw a commitment. Jorginho now goes to the right, and unless McBurnie gets way back and puts himself in this shape — it’s a 5v4 again.

We saw some of those heavy wide shapes on the right throughout. While Saliba has done this opportunistically in the past, the degree of commitment was higher. Opponent quality no doubt had a part to play.

And you can see how aggressive it was still on the left.

Now, we shouldn’t read too much into a performance against Sheffield United.

But in many ways, this was a product of seasonlong evolutions: Raya’s ability to play “CB,” Gabriel gaining comfort at CCB, White/Ødegaard/Kiwior’s time in the pivot, the Jorginho/Rice pivot, and more. We’ve continued to see it since.

Combine that with Kiwior at left-back, and the opponent loses a coherent strategy for an out-ball — there’s no clear vulnerability to hit on the counter.

In sum, that’s how you get this.

🔥 Ramsdale and Raya

Here was the conclusion of my long piece on Raya, written before he was signed.

That is another characteristic of Arteta’s moves this summer: a devilish impatience to get Phase 4 moving.

This logic, then, seems to extend to the question at hand. Should we continue to put our eggs in the Ramsdale basket, or see how the year goes, then look for competition?

“Now.”

That’s why I’d err to the simplest explanation. I think they’re interested in Raya because they think he’s a level better than Ramsdale, as I do, and they had expected his ultimate sale price to be higher. When it actually started looking more viable, they started moving.

You may think to yourself: this still seems like a lot of money for marginal gains.

I consider him more of a genuine upgrade, but even so: marginal gains have compounding effects that reverberate throughout the pitch. At this level, marginal gains are all you have left.

If nothing else, the last week or so has felt like a blinking validation of this summer’s transfer business.

Rice scored. Havertz scored a winner. Raya saved the day.

The save against Wendell (the first save in the sequence) struck me as pretty special.

But penalties can be fickle and highly “varianced,” of course.

The more durable takeaway was from the rest of the game. Last week, we got a Ramsdale start. With it, we got the full Ramsdale experience: incredible reaction saves, relentless energy, and the odd mistake. Here’s what I wrote about him in that same Raya scouting report:

But the best reason to be excited for Ramsdale is for his performance relative to age. He is very good already, occasionally sloppy and impulsive, and young for a keeper; if you believe he keeps up that trajectory, he’ll be in that highest tier in no time. Speaking personally, I think either of these scenarios carries an equal chance of coming to fruition: a) he turns into a bonafide star, or b) he continues on as a distinctly above-average keeper with a persistent, and sometimes-frustrating “vibes” element to his game.

In the end, we saw the difference between the two, which is often subtle. While the objective of a long pass is not always a “true” completion, this still tells a story.

In the end, Ramsdale has shown a more understated version of the questions that have faced some previous Arsenal players. That is: even when they produce an individual performance that pleases the eye, there’s an unmistakable bounciness that gets added to the proceedings — a little less control, a little more variance, a little more need for individual heroics. That kind of thing is welcome when you are the overmatched side, but not always when you are the one who is consistently doing the overmatching.

Against Brentford, Ramsdale has the most launches of the year for an Arsenal keeper (24), the highest launch percentage of the year (66.7%), and the highest length of pass (47.1 yards). Perhaps interestingly, he had the most crosses stopped of the year, as well.

On Raya’s side, he has the best cross stoppage in Europe (by a distance), and is also in the top-5 for the highest defensive actions. When I wrote the “bear” case for his signing, I said this:

Goalkeeping is communication by another name. Passing, scheme, shot-blocking, corners, free-kicks: it’s all a team sport. Any new keeper carries some risk of settling in. Brentford’s system is not always similar to Arsenal’s, and there could be some awkward moments that lead to significant questions.

If he’s worked his way out of that period, as he seems to have done, the arrow is pointing up.

🔥 Wrapping up

I have much else to say. I’d love to talk about the composure of Kiwior, and how his trajectory has been a fail-safe for Arsenal right when it was most desperately needed. I’d love to talk more about the steeliness of the penalties, Trossard’s finishing, or how Jesus just makes things happen. Have I written enough about Havertz? I hope.

But for now, with a longer break ahead, I’ll wrap it up — and will return before too long to talk about Man City, Bayern, and a whole lot more. I might even try to write something on Mika Biereth. If you have something you’d like covered in more depth, please drop it in the comments.

I happen to write these newsletters a couple of days after the games take place. I hope that the “analysis” side doesn’t feel cold, as it often can. I hope it enriches your experience, and never strips away the humanity, joy, dismay, highs, and lows that this sport (and this club) can produce with such regularity.

That was a special week. Here’s to more to come.

Be good. And happy grilling. ❤️

A wonderful column, dissecting a fabulous week for us. I do not mind the delay, as it gives us time to look at games objectively after our euphoria has settled. And I would love a part and parcel on Kiwior. Watching his game grow this year shows another phase of how astute our business has been. He has been wonderful to watch mature in the Lb "role." Cheers, and keep it up!

🎶We've got super Bill Carpenta🎶

(Another excellent article. I'd love to read your analysis of Kiwior, and anything about the profiles you feel the team should go for in the summer window)