Profiling Martinelli

An examination into where he plays best and how to continue unlocking the full potential of a 21-year-old who is already great

Let us start, as we must, with the LOLs.

In a detailed story by The Athletic about how the Mykhailo Mudryk saga unfolded, there was a buried gem. Late in the ordeal, it was up to Chelsea executives to make a closing argument. Among the points they chose to emphasize with Mudryk, one was that he needn’t fear — for, despite their infinite signings and freedom dollars, he will not have to compete with a certain winger for game-time:

Eghbali and Winstanley stressed how he would arguably face stiffer competition from 21-year-old Brazil international Martinelli if he chose to join Arsenal.

They have not been alone in their praise. Guardiola called Martinelli “an incredible weapon.” Klopp called him “a talent of the century.” And behind closed doors, Rio Ferdinand shared that Arteta told him “there’s a bit of Suarez in there.” The rest of the Ferdinand quote—shared after the I’m Him display against Liverpool—was funny, too:

“He’s a bad player. He was the wrong ingredient for Trent when he’s searching for confidence. The wrong ingredient. He did not need that!”

It’s been an eventful year for the young phenom. He started the campaign with back-to-back goals, and amidst injuries to his colleagues, has since solidified his place as the locked-in starter at left-wing for a top-of-the-table Arsenal. He completed an uphill battle to make Brazil’s World Cup squad over the likes of Firmino. And after requesting a pen, he got a pen—no, not that kind of pen—and he signed a new four-and-a-half-year contract to stay in North London.

Still, after a few uneven performances that coincided with the absence of compatriot Gabriel Jesus, some questions remain. (Luxury questions, it must be said). Namely: with his work-rate and determination, he can be pretty excellent at virtually whatever he does; but what is the best way to utilize this incredible young talent?

Lows and Highs at Everton and Leicester

No title run is a straight line, and the performances of Martinelli and Arsenal bottomed out in lockstep. Facing the irrepressible Dyche Bounce at Goodison Park—why did that feel inappropriate to type?—he battled with endless wide double-teams in a disciplined, muscular, 4-5-1 block.

He’d accept the ball around here and look to make the difference down the touchline:

It didn’t go so well. As you can see in map of his total actions, much of his work was in isolation out wide, in what might be categorized as “Zone 10” or “Zone 13.” He managed only two total touches in the box, had some loose touches, and never really threatened the goal:

Against Brentford, things started to unstick. Martinelli made a conscious effort to free himself and increase his dialogue with the rest of the pitch, as we can see in the direction of his total passes:

Perhaps the clearest example was within seven minutes, when he freelanced through zones to nearly drive home this Ødegaard pass through the middle:

The underlying numbers showed a sea-change compared to the Everton beat-down, but unfortunately, the result was still a 1-1 draw. (For the sake of the focus and length of this post, we shan’t revisit why that was a draw.) Reasonable questions were asked about whether Martinelli was feeling the burn of a relentless schedule, whether he was being used correctly, or whether he was crying out for Jesus’ untethered ways.

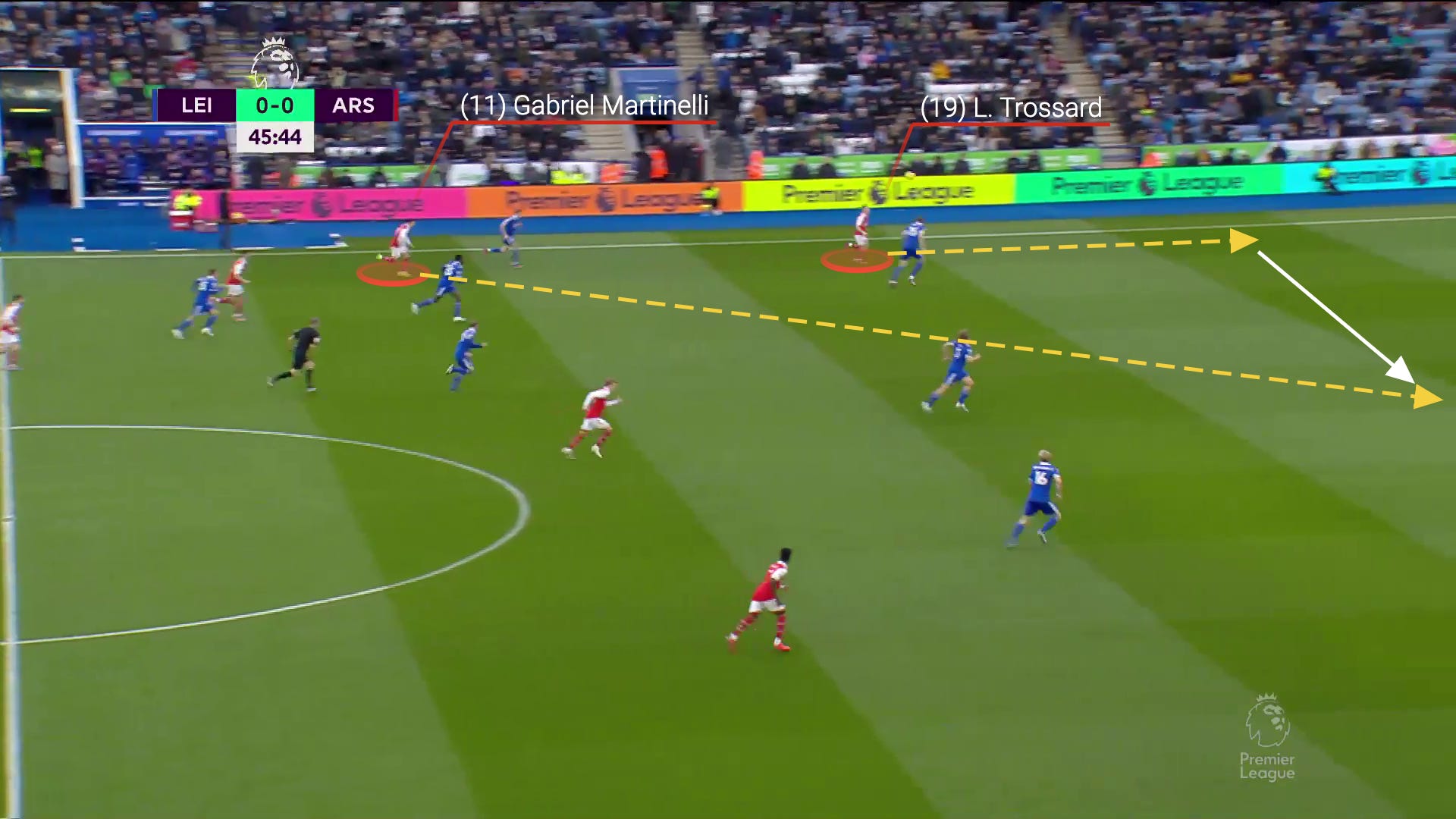

Fast forward a couple weeks to Leicester, and we got some data on the final question. Leandro Trossard jumped in for Nketiah at the 9, and with him carried a lot of the left-leaning expressionism that Jesus brought to the table. If Martinelli’s early-season exploits are still fresh in your mind, it’s no surprise that the goal came when Trossard swung out wide and Fast Gabi made a speedy cut inside:

For another moment, we can dive into the locked-in Saka penalty that wasn’t. Martinelli accepted the ball out wide in classic inverted winger position, then Zinchenko underlapped and Trossard moved to fill the vacated half-space:

Now, with Zinchenko holding width, Martinelli does a little 1-2 with Trossard and starts cutting across zones:

Joining a front-five, the ball is worked out to White, who is being overlapped by Ødegaard. The midfield two is Xhaka (in Zinchenko’s spot) and Jorginho.

White crosses it into Saka, who is promptly rugby tackled near the 6-yard box. No foul:

Perhaps most interestingly, Arteta shared afterwards that he had a flexible gameplan, which may have involved Martinelli switching into the 9 in a more concrete way:

“We had the option to play Gabi as a nine and Leo on the left, we had to see how the game developed and what Leicester wanted to do. I wanted to have that option from midfield to make that change if necessary, and it was great because I think his contribution was really good.”

We don’t know what would have made such an option necessary in Arteta’s mind. If I were to idly speculate, I’d guess that if Leicester decided to double Martinelli wide, Arteta may opt to switch the two—making Trossard more of a wide playmaker and forcing the opponent to choose whether to leave Martinelli a little less marked in the box. But who knows.

Where is Martinelli best?

It probably says something about Arteta’s faith in Martinelli’s mindset that, upon inking his contract extension, his attention quickly turned to where he can improve:

“When you ask him, he can develop physically, he can develop mentally, he can develop in terms of consistency, he can develop defensively and develop in the final third and the spaces that he occupies. His numbers can be improved. He’s so willing, that’s the best thing about Gabi.”

For this piece, I went back to watch some of his Ituano tape, even going back to some of the U20 stuff to understand his instincts. In a 3-0 win against Red Bull Bragantino in the Campeonato Paulista, he started a goal from here (and ultimately put it in himself), which is probably the kind of thing would have gotten him noticed if he hadn’t been noticed already:

Martinelli ultimately was a flexible attacker, with time spent on the right and centrally, but mostly on the left. From what I’ve seen, he stood out most for two traits: speed and control in the transition, and savvy movement in the middle of the box to score on rebounds and tap-ins.

Here, he’s tightly marked in the box, but is able to do the Benzema thing of sticking in his defender’s blindspot and manipulating space:

…and before the marker realizes it, he’s created 5 yards of room for an easy tap-in:

In his first interview as a new Arsenal player, he was asked who he patterned his game after:

“I model my game on Cristiano Ronaldo. He is a player who works hard, pushing himself to the next level. Always in the run for titles and individual trophies.”

Martinelli announced himself with a run of starts in the Europa and Carabao in 2019. He didn’t have the flair or skill moves of a young Ronaldo, but once he got going, he had a quick, glued-on, head down, chugga-chugga thing that was almost eerily similar.

In his first four starts—all at striker—he had 7 goals and 1 assist against the likes of Nottingham Forest, Standard Liège, Vitória Guimarães, and a brace in that absurd 5-5 Liverpool game that went to penalties (which he also converted). What he lacked in polish and strength he made up for in pure tenacity.

Throughout that period, both Martinelli and Emery shared that his eventual role was to be found on the left, and oddly enough (considering that early production), he hasn’t had another run of games in the middle since.

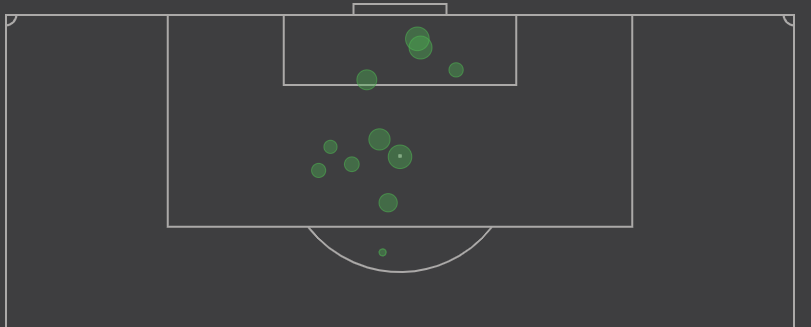

Looking at all of his goals before this season, we can see how central they are:

I went back and watched all his career goals/assists, jotting down quick notes, and wrote something like “angled run through the middle” on a good 90%+ of them.

A typical goal during this period looked like this. With Lacazette false-9ing, the left channel is open for Martinelli to sprint through. It’s important to note that Martinelli is not the one holding width. It’s Tierney who is forcing Coufal to shade wide:

…and the winger completes what should be known as The Martinelli, a perfectly-placed, direct, falling away shot to the far post:

This year has brought a confluence of factors that can feel hard to separate, and the conclusions can feel counterintuitive. Thanks to changes elsewhere (largely the inversion of the full-back behind him, and the pushing-up of Xhaka beside him), Martinelli has taken up a spot as the widest player by default. As a result, he’s been pushed closer to the touchline, and further away from goal:

But because of the improvement of the team’s overall form, quality, and possession %—and the degree of freedom with which he and his teammates, particular Jesus, play—he has still been able to notch more touches overall, and more touches in the attacking penalty area.

In other words: the role is more isolated on paper, but less isolated in practice. (Great analysis, Billy, thanks!)

He almost always looks his best in transition, or when he’s playing with a degree of expressive freedom. Against Leicester early in the year, Jesus attracted a crowd while drifting right, allowing Martinelli to sprint through Zone 14:

After receiving the ball with a little space, he sees a crease and goes for it with his left foot. Goal:

Within four minutes against Nottingham Forest, he’d gathered the ball after a counterpress, and changed play to Saka:

Then, by sprinting through the central area (vacated with Jesus out wide), Saka hits him with a cross and he heads it home:

There’s been two headed corners, two near-post rips, and memorable moments in transition: the Liverpool opener, the Liverpool first-half closer, the Liverpool dribble leading to a Xhaka goal; the beautiful outlet ball from Odegaard to spring him against Brighton.

As such, we can see his shot chart floating left. The greens are the goals:

The output has followed: Martinelli had outperformed his xG, and his goals/90 is higher than that of Vinicius and Saka, and on par with Leão.

Where has he struggled?

We should probably begin by saying that reports of Martinelli’s struggles are probably overstated.

Post-World Cup, his game has been broadly similar, but there are a couple things worth noting. Here’s an ugly graphic I made in 11 minutes to honor him:

His overall activity has been largely similar. His shots have been less accurate, his dribbles have been a little less successful, and he’s lost the ball a bit more. He’s taken all of 19 shots post-WC, so it’s not exactly the most statistically significant data pile.

The biggest things that stick out are that he’s touching the ball in the penalty area more, but passing it in there less. This might seem like an OK thing as he takes more of an alpha role, but the tape shows that all touches are not created equal.

First, he and Nketiah have, indeed, not found an ideal chemistry. Against Manchester City, Gabi sent two passes in to the striker, and received one in return. Against Manchester United, the two didn’t exchange a single pass.

This has directly impacted Martinelli’s overall game. Looking at the tape, you’ll see a lot more straightforward sprint-dribbles down the wing that start deep and don’t necessarily amount to much (like we mentioned against Everton).

In the box, you’ll see more situations like this, where nobody’s holding width and no particularly dangerous cuts are happening, so multiple defenders can squeeze him out:

These factors—a bit more ball-dominance, and a role more likely to be isolated 1v1 on the wing—have had some knock-on effects. One example is that while he is attempting take-ons more, he’s succeeding less. His success rate has dropped from 57% last year to 41.6% this year.

I pulled per 90 data for Gabi and four other iso wingers that offer stiff competition: Saka, Vinicius, Leão, and Kvaratskhelia. While he kept pace in some of the big stats (like goals and shot accuracy), he lagged behind them as a playmaker, ranking last of the four in key passes, assists, shot-creating actions, attempted take-ons, progressive carries.

This tracks with the eye test. Compared to that world-class company, he can be a bit more straightforward in moments like this:

While the others may pull from a bag of step-overs, hip-fakes, body-feints, or unexpected passes, defenders can safely assume that Martinelli is either a) trying to burst around them on the touchline or b) slowing things down.

There are a few other oddities to his game this year:

Despite his wonderful work-rate, he’s become increasingly ancillary in raw defensive activity. He’s won 10 tackles (total) through 23 starts, and is only 3-of-12 when facing down dribblers (25%). According to FotMob, he’s tied for 10th on the team in possession won in the final 90 (.4 per 90).

Despite being pretty good around the goal with his head, he’s been in less successful aerial situations this year. Some of this is because of Ramsdale blasting kicks his way in hopes of securing second balls, but it’s still not ideal. He’s 9-of-39 aerially, for a 18.8% win rate.

He’s underperforming his xA numbers, tallying 2 assists in league compared to a 5.1 xA.

With all this information, let’s talk profile.

Profiles, Profiles, Profiles

Sometimes conversation about profiles can feel a little academic and gate-keepery: “no, it is I who holds the authoritative definition of a regista, and you, my friend, are no regista.”

That said, any discussion about how to make sure a player is in the best position to succeed is a valid one, and Lord knows my dumb ass will participate. After all, the majority of the Arsenal lineup is not in the position they were playing when they originally joined the Premier League.

Discussion about the best use of a wingery goalscorer is certainly not new, and that is because many (most?) of the best players of all time are wingery goalscorers.

What is important to note here is that Martinelli is a little different from others of his inverted-winger “generation,” of which I’m haphazardly including Saka, Vinicius, Leão, and Kvaratskhelia for now. While he has the raw physical traits of any of them, he is a little less imposing as a pure 1v1 mark when he has the ball: he is a direct speed-train to the net. In a 1v1 situation further away, he can have fewer options in his bag, and be a bit more predictable as a result.

While he may not match up on their terms, he certainly matches up on his own. He combines an astronomical work-rate with a higher defensive projection than perhaps anyone on that list. His subtle box movements and sense of space may outpace any of them, as well, and he has a certain knack for clear-eyed, deceptively simple finishes.

As such, he deserves a role all his own. His own model, Cristiano Ronaldo, went through a similar transformative process, first from wide right midfielder in a 4-4-2, then to an inverted left-winger, then finally to a striker. While researching this article, I came across this piece about Ronaldo’s changing role for Real Madrid, which may lay out a bit of a guidebook for properly utilizing Martinelli:

What exemplifies Ronaldo’s increase in attacking instinct, is that rather than receiving the ball in deeper areas of midfield, and aiming to create a chance through breaking down the opposition defence, Ronaldo now makes off ball runs from the left hand side of the “BBC” (Bale, Benzema and Cristiano) front line. As a result, Ronaldo can receive the ball further forward, possibly in a greater amount of space, and have more effect on the outcome of chances.

Try as he might, Martinelli is also not a Ronaldo clone either. Turns out scoring 800 goals is hard.

Raheem Sterling comes to mind a bit. In his best years at Manchester City, he used his speed and positional genius to relentlessly poke and prod the opponent’s backline. But reviewing the findings of this piece—savvy in-box positioning, wingery instincts, gargantuan speed, ridiculous work-rate, “total football” mindset, directness in goal-scoring—a name kept coming up in my head as a guidepost: that of Sadio Mané.

They are not carbon copies of one another, but I believe they constitutionally see the game in much the same way:

How to best use Martinelli

There are two situations in which plugging Martinelli in would require the least amount of managerial creativity. The first I would posit, believe it or not, is in a Simeone/Conte type side. After watching more Atleti games that I’d care to mention, in an effort to understand how and why João Félix was being misused, I couldn’t escape the thought that Martinelli would thrive in a rugged defensive side with 2-3 high forwards that look to spring clean, fast, uncomplicated, direct counters.

The second such situation is in a Kloppian Liverpool side. Perhaps the single player that reminds me most of Martinelli is one Luis Díaz, who is five years (!) older than the Arsenal man. (We should never lose track of how young these guys are, and how much potential they have left to show.)

With overlapping full-backs holding the wide-space, Klopp’s wingers have historically been able to crash the narrow zones and spend a lot of time in the box, and get all the way to the goal through the vacated zone of a false 9 striker. This enables somebody like Mané to be a forward and a winger at the same time:

That’s the ticket. But players like Ronaldo and Mané have had something in common, of course: a player holding width. By default, the 22/23 Arteta system does not afford Martinelli that luxury by default. That means it’ll have to be manufactured.

Looking back at the games he’s started at RW, I believe Martinelli should be considered legitimate depth there. Like a Kingsley Coman or Sterling, his game doesn’t seem to fully depend on inversion. His sprints down the right line with a more shielded body shape can yield results, and he can be skilled at one-touch crosses with his dominant foot. Plus, who can forget this one touch finish after he cut in from the right:

His ability to truly rotate out there should offer more flexibility with future signings.

As a pure striker in this system, there is a little bit more of a mixed bag. His runs, probing, and finishing would look right at home. That said, this team has been shown to be at its best when the striker is dropping deep and acting as a playmaker, and I’m a little less enamored with his potential with his back to the goal, or when keeping his head up to an array of runners in front of him in settled possession. It’s an option, but having him cut centrally from the flanks seems preferable.

️🔥 In conclusion

When a player starts reaching Martinelli’s level of production as a 21-year-old, it’s safe to say you have something special on your hands. As such, the goal shouldn’t be to neatly box him into an existing profile, but to craft a role that best suits the unique abilities of he and his team.

After going through this exercise, that role seems, to me, to be a midpoint between an inverted winger and an inside forward, relying less on wide 1v1 take-ons and generating as much off-ball movement, transitional moments, and central touches (and shots) as possible. To achieve this, he can combine some of the aspects of Ronaldo, Mané, and Sterling’s best roles to create a tactical way of playing that is uniquely his own.

But given the realities of the system—and specifically, the fact that he doesn’t have wide help built-in—how can that be achieved?

Here are a few thoughts on unleashing Martinelli in the months and years to come:

To confirm a #narrative, he is, indeed, being impacted by the loss of Jesus. This is both because of where Jesus plays—swinging out wide left like Trossard did, attracting a crowd—but also where he vacates: the central area is more wide open for Martinelli cuts. The idea shouldn’t be to perfectly delineate who is the winger and who is the striker, but to continue blurring the lines of the two to where they’re virtually indistinguishable. Total football, baby.

In the meantime, it seems clear that Martinelli operates best with another player offering wide help (as most wingers do). In transitional moments, Martinelli should seek the ball in the left half-space (not just the flank) and be patient in waiting for overlapping runs from Zinchenko and Xhaka while breaking down the defender.

In more settled possession, there are a few ways of getting width. One is through looping underlaps. As we saw above, the best way to achieve that with the current starters may be to have Xhaka drop into Zinchenko’s spot, Zinchenko underlapping in the half-space, and then looping around to the widest role. (No, I don’t expect the LB to suddenly turn back into a Tierney bombing/overlapping situation again any time soon—there a lot of good reasons for that, and this is ultimately about somebody holding width and not just about overlapping, etc—but a couple more a game could be in the offing).

In the years to come, Martinelli will naturally be able to drift centrally through a more wingery player in the left-8. The more central his play, the more he gets to dialogue with Ødegaard, the better.

In terms of play-style, it’d be nice to see a few things continue to evolve in the short-term: a little less reliance on straightforward 1v1’s far away from the goal, a little more prodding the back-line for through-balls in advanced areas, and (maybe most importantly) a lot more Martinelli-triggered rotations. So many of the season’s best moments have not been through “automatic” rotations, but through a player like Martinelli simply deciding to do some shit. If things are getting stuck like they did last time against Everton, I don’t think there’s such a thing as too much unexpected cutting, rotating, cross-zone dribbling—and in Jesus’ absence, Martinelli is the front-line player most capable of providing it.

I don’t believe the current Arsenal shape is fully capturing his value as a defender or sprinter at the moment. Now that the press has leaned more man-to-man, he can be seen marking decoy full-backs more, shading back towards Zinchenko, and is a little less disruptive and involved than he could be. Whenever the team eases into its 4-4-2 block, I can’t help but picture Jesus and Martinelli leading the line in the future (instead of a striker and Ødegaard, as it stands). That makes things a little tricky in the “mid” part of the mid block, but an asymmetric 4-4-2 was a key for some of those Zidane Real Madrid teams: with Jesus up top as a target man (where Benzema was), and Martinelli taking up spots that are high by nature (where Ronaldo was), the team is purpose-built for nasty transitions.

I don’t see any reason he shouldn’t be snagging starts across the frontline in years to come, and have his gamelog look a bit more like a Mané’s: mostly LW, some RW, a false-9 start here and there. Later in his career he may grow to lean more strikery.

OK, went a little overboard on that one, particularly considering that I introduced this as a “luxury question” and an area of the team that is already going pretty swimmingly. Oh well. It’s exciting to see all of Martinelli’s potential in action. It’s even more exciting to see all the potential left to realize.

While I regret nothing, I also stand by nothing.

Happy grilling everybody. And remember to sign up for this newsletter if you haven’t already.

️🔥

Loved this. And loved seeing Martinelli pop up on the right for Saka's first goal today. His presence disrupted the defender's attention for a split second, allowing Zinchenko's pass and Saka's turn for the right footed goal.

An excellent read, I like your writing style. Thanks