Takes One to Know One

How Bukayo Saka's formative experiences at left-back helped him become one of the world's most dominant wingers

Bob Dylan tells us that life isn’t about finding ourselves, it’s about creating ourselves. If that’s the case, Bukayo Saka is quite the artisan.

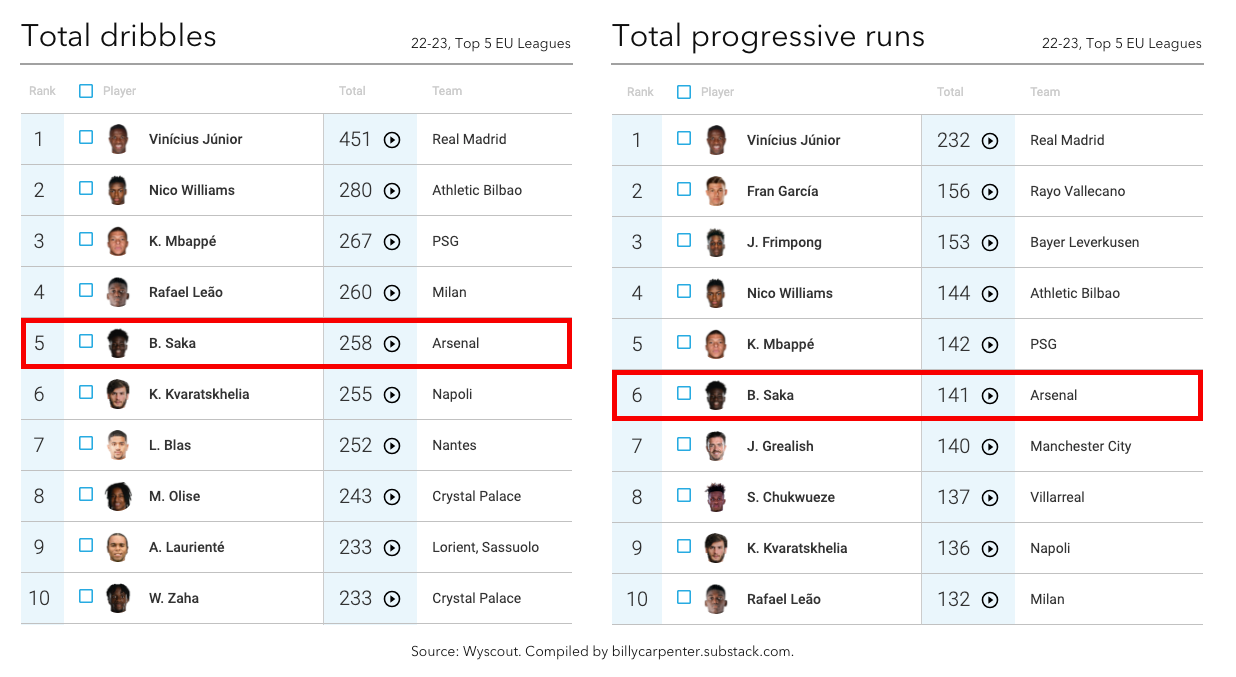

By any measure, he has built himself into one of the most skilled one-on-one dominators in the world at 21-years-old.

He led the Premier League in touches in the attacking third — with 193 more than the next highest player, Bruno Fernandes. He attempted the most take-ons in the league, with 161. He led the league in progressive carries, which is a good indicator of winger impact (for reference: rounding up the top 5 are Grealish, Mitoma, Martinelli, and Salah). He has the most carries into the final third, with 92. And he was #1 in progressive passes received, with 520.

Across top leagues, his numbers still shine:

Oh, and he had 25 G+A in the league, while often looking like England’s best player at the World Cup. A long-term deal followed, cementing his place as one of the most valued talents in the game. Transfermarkt currently lists him as the fourth most valuable player in the world, and the top right-winger.

Not bad for a guy was playing left-wingback for England as recently as last September (oh, Gareth), and who was born 19 months after Arsenal’s recently-signed, regularly-developing, longer-term project centre-back (Jakub Kiwior).

Saka is unique for many reasons. Not least of which is his experience at the very position he now faces down every week. In total, I found 3,710 minutes played as an LB/LWB, going back to his U17 days, which is the equivalent of 41 full-90s.

After establishing himself as a Premier League regular at the position due to injuries ahead, the teenage Saka had this to say:

"I've learned a lot about how wingers in the Premier League play against defenders and how to position myself … In the future if I do get to go back onto the wing I feel like I know how full backs play and playing as a full back I know what wingers do, what I like them to do and what I don’t like them to do. It’s a good learning experience for me.”

So: how did this espionage at left-back inform his work against them as a winger?

After looking back at all his defending duels from those days, and relating them to his work as an attacker, let’s explore.

The heart of the duel

There is no one “correct” way to defend, as you will no doubt tell me in the comments, but it may be helpful to have some overarching concepts to discuss. So to begin, we’ll dramatically oversimplify the defensive responsibilities of a full-back in a 1v1 duel.

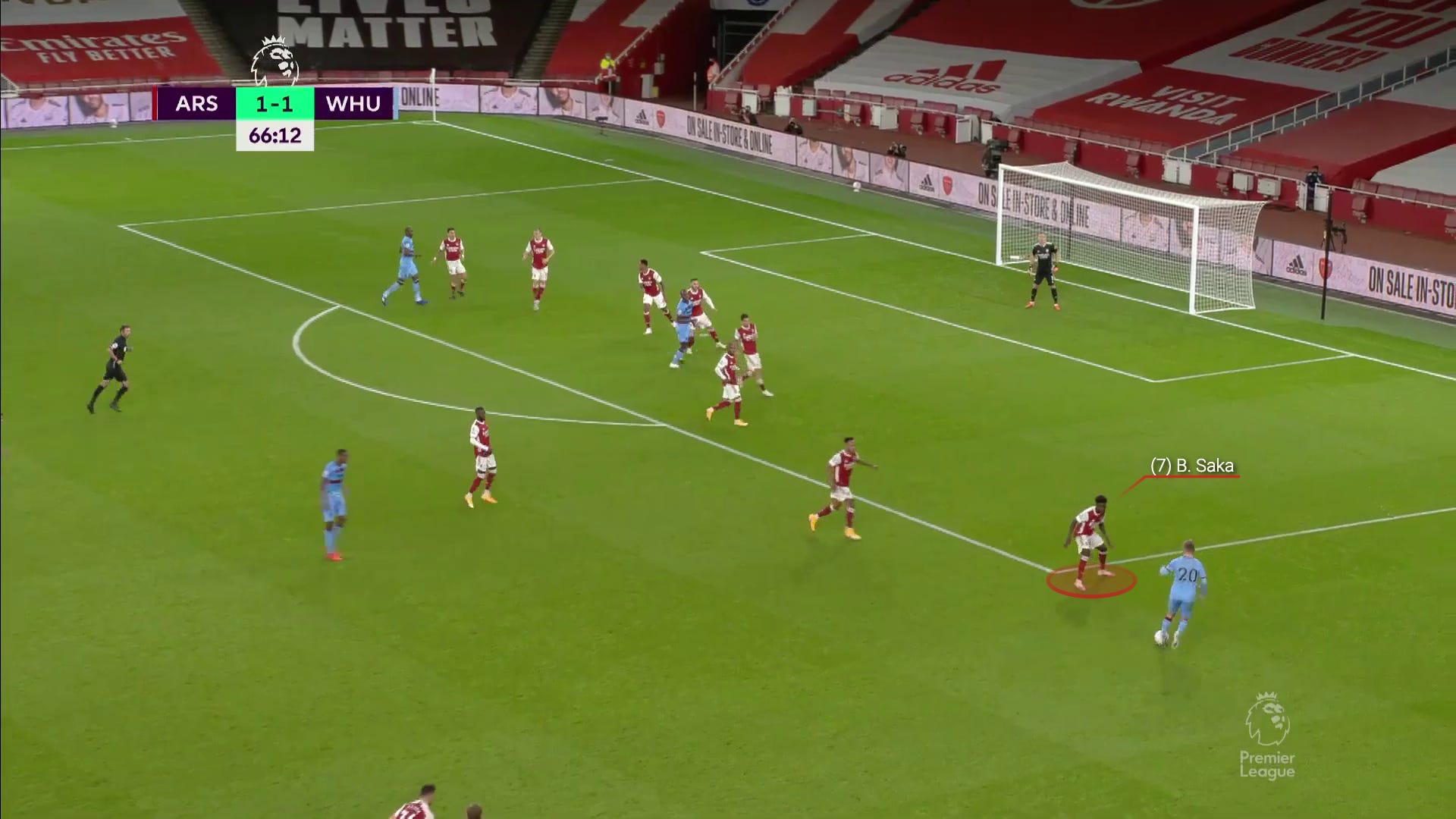

Here is the standard image of a full-back. They’re slightly crouched, on the balls of their feet, hands near their waist for balance, angled towards the direction they’d like to lead the player, and hopefully, not indiscriminately lungy. Saka here is leaning back and sideways a bit while he pushes Bowen wide, taking little steps along the way:

But really, the engagement starts before this. For today, we’ll look at three key moments in the matchup, and what a defender may be looking to achieve:

The reception — Unless an immediate interception is possible (which is unlikely on the wing, and more liable to cause a defender to get caught out), the defender will try to arrive around the same time as the ball, putting weight on the attacker in an effort to unsettle the first touch and disrupt the reception.

The dribble — From there, the defender should look to patiently shepherd the opponent to a place of less threat, usually away from the goal, as we see Saka doing in the screenshot above. This task — proper positioning — is the heart of defending.

The tackle — Once engaged, there are two real opportunities for a dispossession:

A loose (i.e. unintentional) touch: If the ball momentarily gets away from the attacker, the defender should look for the perfect time to poke it away, and not lunge promiscously.

A long (i.e. intentional) touch: If the ball is purposefully flung forward in an attempt to get by, the defender should look to win position first (instead of always going for the ball).

With that as our basis, let’s dive into these areas to better understand how Saka’s backline experiences have shaped his strategies as a winger.

The reception

Arteta is very clear about how he prefers his wingers not to receive the ball:

"I don't like creating lines between the wide players. Why? Because the full back passes to the wide player like this. His back's to goal. He can't progress the play. There's always someone at his bum. He cannot play forward.”

As a full-back, Saka knew how to pounce on these situations.

Here, with Mahrez accepting the ball out wide and without progressive options, Saka arrives a touch late, but still uses his leverage and positional advantage to drive him all the way back to the goal:

As a winger, Saka tries to avoid these situations whenever possible. He does this in two ways.

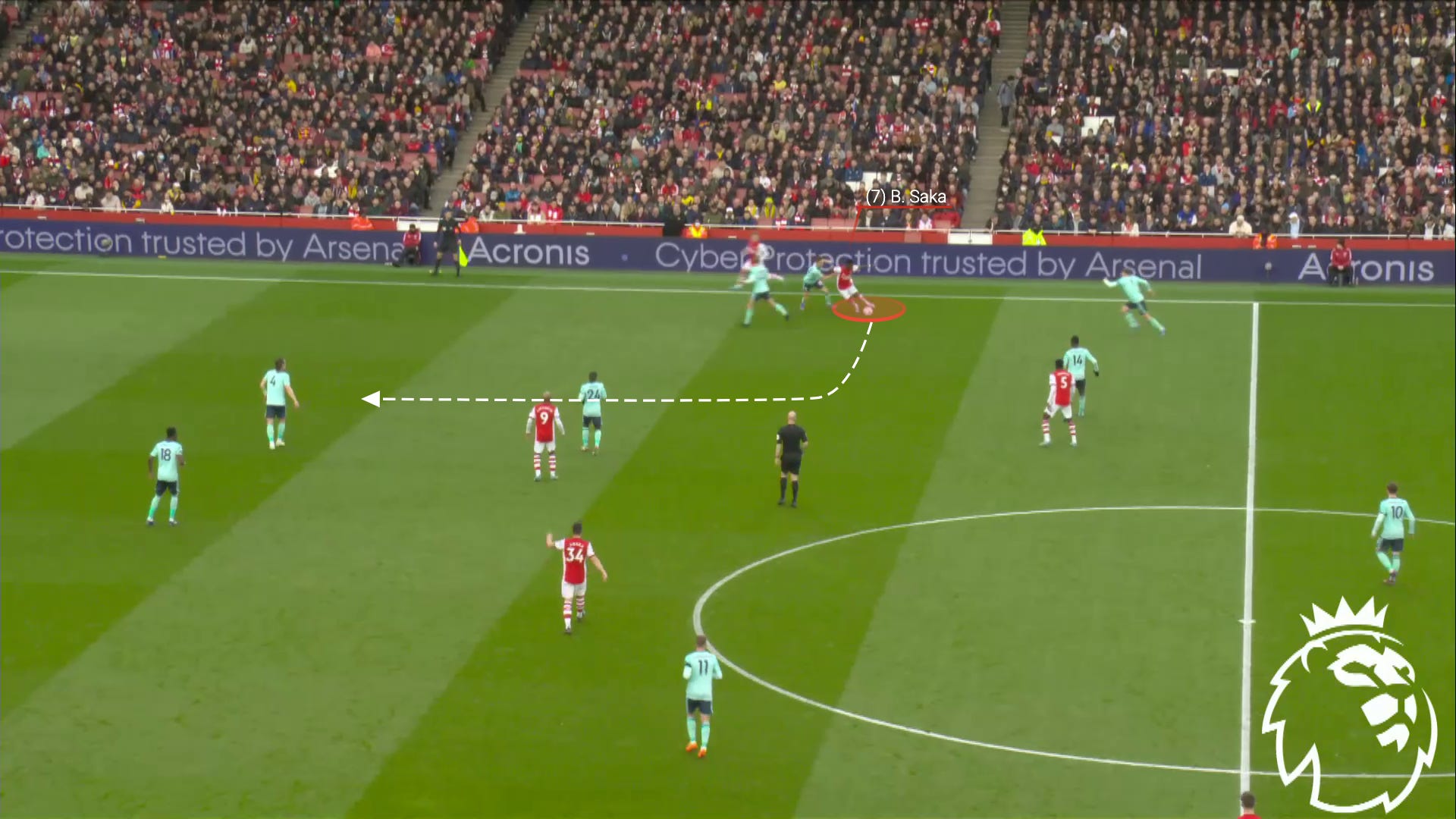

The first is in his interplay with White. Especially as the season wore on, they worked in unison to follow Arteta’s direction and ensure that, wherever possible, Saka wasn’t receiving the ball with someone at his back, but moving towards the goal:

These rollers — helping Saka keep inertia flowing toward the goal, and increasing the chance of manipulating a defender’s balance — became a dangerous weapon, so much so that managers like Erik Ten Hag had to make specific schematic adjustments to cut this pass off, dropping players off White to clog the middle of this lane.

As we mentioned, trying to cut the pass out to the winger usually ends in tears in the Premier League. Despite his aggressiveness as a full-back, Saka usually hung back before engaging, though he was occasionally caught out.

As an attacker, he keeps his eyes up while trapping it, clocking the defender’s movements in his periphery. If they’re looking to “jump,” he just opens up his body the other way to get past them:

Here’s another one of those, which I also filmed with a potato from 1974:

Paired up with Trent Alexander-Arnold for England, Saka is increasingly prodding the backline with runs for over-the-toppers, adding another measure of uncertainty for the full-back.

It would be impossible for him to lead the league in progressive receptions without sometimes having a defender on his back, however. In fact, it happens quite often.

In these cases, Saka looks to exploit the exact kind of aggression he showed in those situations. His first step is trying to feel out the defender — he usually extends his arm to initiate contact and soften their blow while gathering the ball. Defenders aren’t accustomed to that amount of fighting from a winger; off the top of my head, only Salah really hand-checks to the degree of Saka.

Hey, guess what position Salah played in his teenage years?

Here, Renan Lodi is determined to defend like Saka might if he was still in the backline — by being physical and knocking him off-balance as he goes to receive the ball. But Saka is returning the hand-checks, which turns it into a scrap, instead of a one-way act of bullying:

Then, when the ball and defender fully arrive, Saka bends his back to a near-crouch. This gives his body the low gravity that has become a trademark of his play. Combined with the bowling ball in his chest that is heretofore referred to as “Saka Strength,” it makes him really hard to push off the ball. Where do you push?

At that point, it’s the defender who is out of control, and Saka can dip his shoulders, fling him off, and turn up the pitch as Lodi looks for a foul for the contact he initiated:

Here, you can watch it all play out in .gif form:

Next, here’s a freeze-frame where the defender seeks to unsettle Saka with his hands, but drawing upon his experience with the roles reversed, Saka beats him to the hand-fight, extending his arm first. This gives him the slight bit of separation he needs to turn and dribble all the way to the box:

These moments have become commonplace. Here’s the one I may love most, where Cresswell is trying so hard to foul but Saka isn’t having it:

From that point, if the defender does successfully gain leverage, Saka is improving at knowing when to give up the ghost and go down. That is, he’s good at drawing the foul, but not necessarily receiving it. (To see that John McGinn drew more fouls than him this year makes me Big Mad, but that’s a discussion for another day.)

The dribble

After the reception comes the next part of the duel: the actual showdown.

At full-back, Saka himself had the hallmarks of a plucky, aggressive, sometimes jumpy defender. When he struggled, it was usually because he couldn’t diagnose what an attacker was looking to do, but stayed aggressive anyway — causing him to impatiently jump at the ball and get turned.

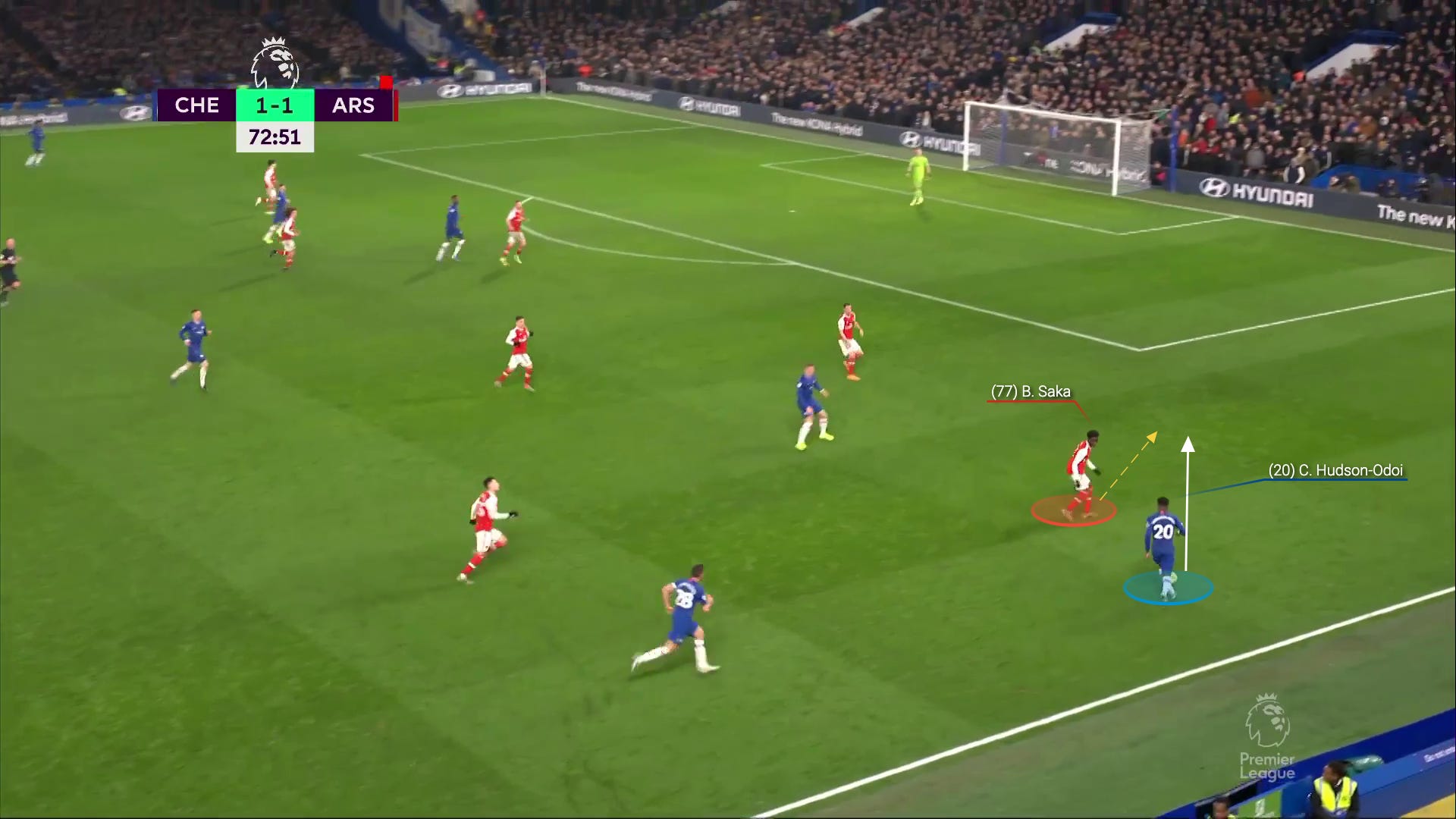

Here, Saka was in OK position as Callum Hudson-Odoi picked the ball up out wide:

…and at his best, Hudson-Odoi could be a handful to face. He keeps his body straight, disguises any intention, and is comfortable going to either side, making his movements unpredictable. As such, he drives at Saka directly and with conviction:

…and Saka is forced to push is weight back the other way. That moment of imbalance is all a good winger needs, and Hudson-Odoi flips him and goes into the space:

These are memorable, instructive moments for a young full-back.

The tale of Kaoru Mitoma writing his thesis on dribbling was much-ballyhooed; over-ballyhooed, even, if you ask the man himself. But when asked for his actual learnings from the process, Mitoma offered this:

“I am conscious of shifting the opponent's centre of gravity. If I can move the opponent's body, I win."

This is the key thing. It can be easy to presume that an “alpha” player will seek to impose their will on the opponent, determining their own action and then saying “there’s nothing you can do about it.” The best dribblers, though, are actually a little more reactive and serendipitous.

Take a stroll through Messi’s career highlights, and see if you can find a single ounce of predetermination:

As Mitoma said, it’s about balance. Messi is making a million little calculations about where a body’s momentum is heading. If the desired leans aren’t naturally occurring, he generates them through feints and changes of direction, all the while keeping the ball close enough to masterfully and immediately exploit them.

The nightmare matchup for a full-back, then, is an attacker who is “intention neutral.” That is, they are not visually showing any signs of running a preprogrammed “move” on you — they are keeping momentum towards you, perhaps changing direction slightly, baiting you into action, or modulating their speed, but above all, they are ever-mindful of your steps. Then, as soon as you show the slightest bit of untoward momentum, imbalance, or jumpiness, they commence the ambush.

The short version of all this? If Saka is coming at you like this, you will not have the faintest idea of what he’s going to do, because you will probably make his decision, not him:

Mitchell had a heavy step on his back foot in this case, so Saka did a stepover, cut to the byline, and fired in a low cross with his right.

At these levels, the duel is so detail-oriented that you’ll see a defender like Aaron Wan-Bissaka fake these heavy steps to trigger movement from the attacker.

Now, much can be said about the repertoire of options Saka has at his disposal: shots and passes with either foot, crosses, 1-2s, speed-bursts, and more. It’s taken a great deal of work to get so good at so many things. But I’d suggest that there are lesser wingers who are a little more ambipedal, a little faster, or even have a slightly higher ceiling with ball-striking. What makes Saka so great is the alchemy of all these traits, combined with his strength and his brains.

But more granularly, what may be undercelebrated is his ability to mask any shred of intention before the time is ripe.

The tackle

Which brings us to the currency of the defending full-back: the tackle and/or ball recovery.

As with wingers, defenders can get into trouble when they predetermine their action, deciding to a) go for the interception too early, or b) stick their foot in, irrespective of what the attacker is doing.

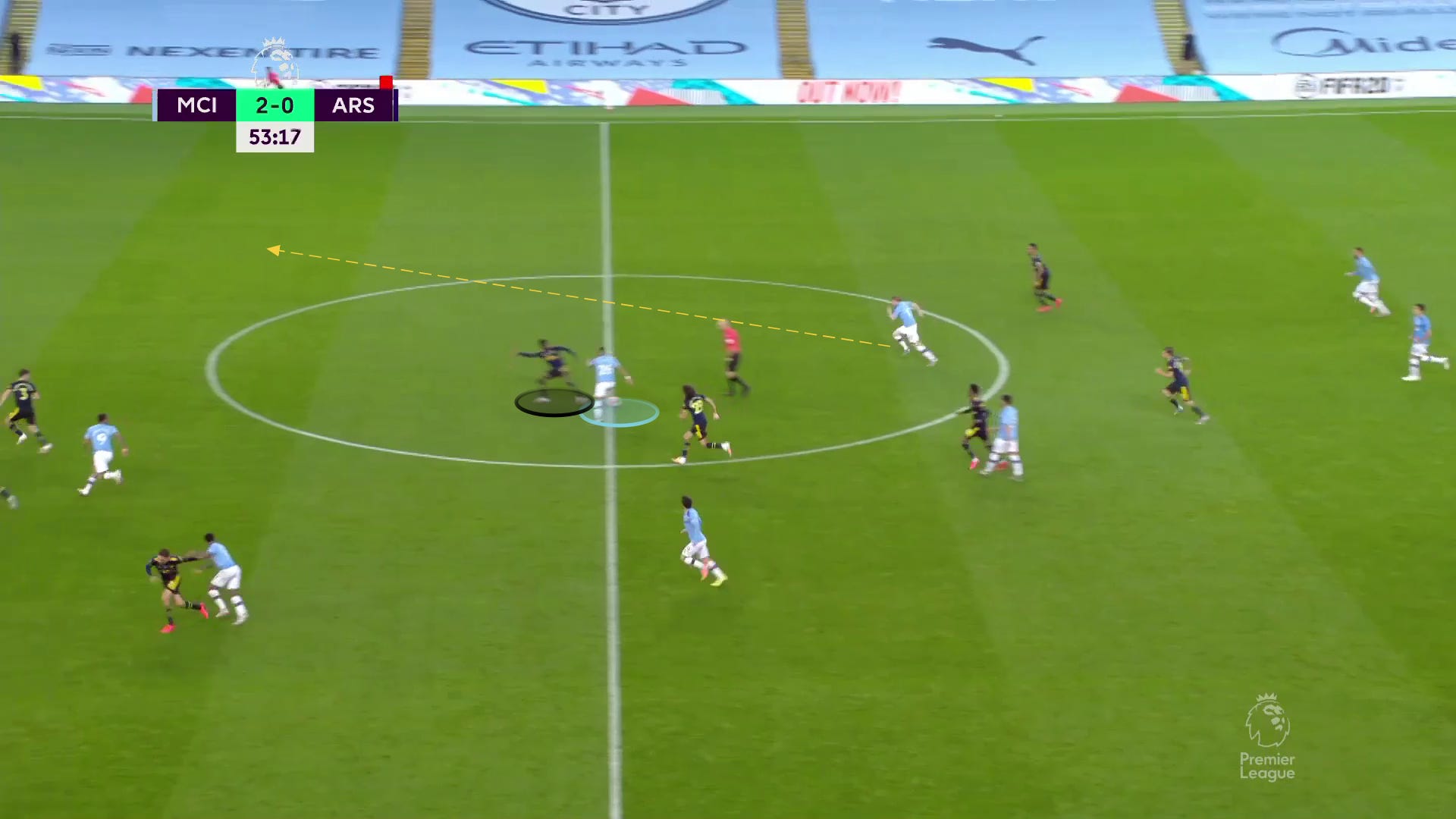

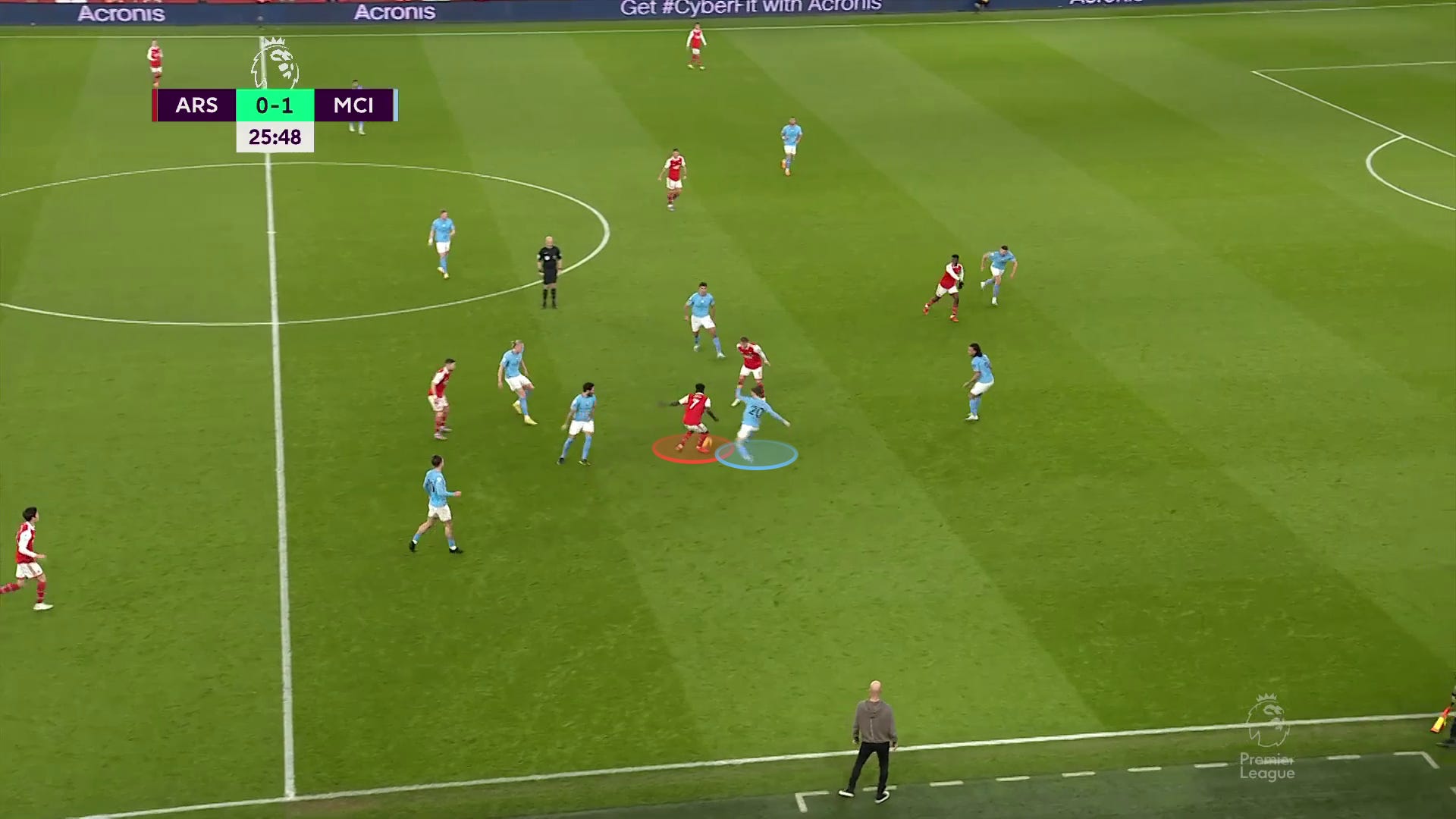

Saka could be guilty of this back in the day. Here against Man City, he lunged at a Mahrez dribble, even though there wasn’t much to lunge at. With De Bruyne making a run behind, it could have been dangerous:

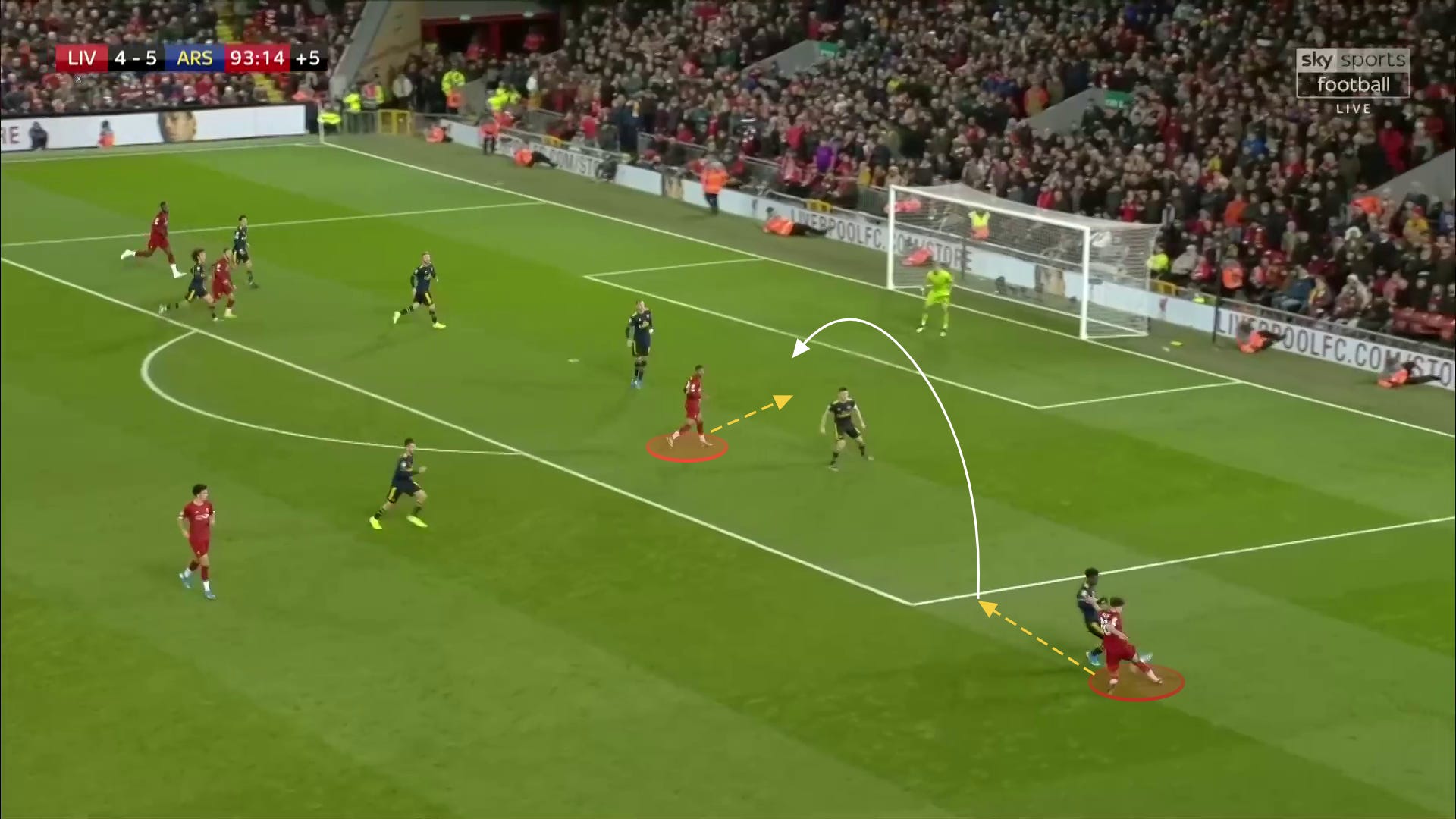

Here against Liverpool, he sprinted out to the wing and overcommitted against Neco Williams, allowing him to cut back and cross it in:

As a defender, the more discerning he was, the more successful he was.

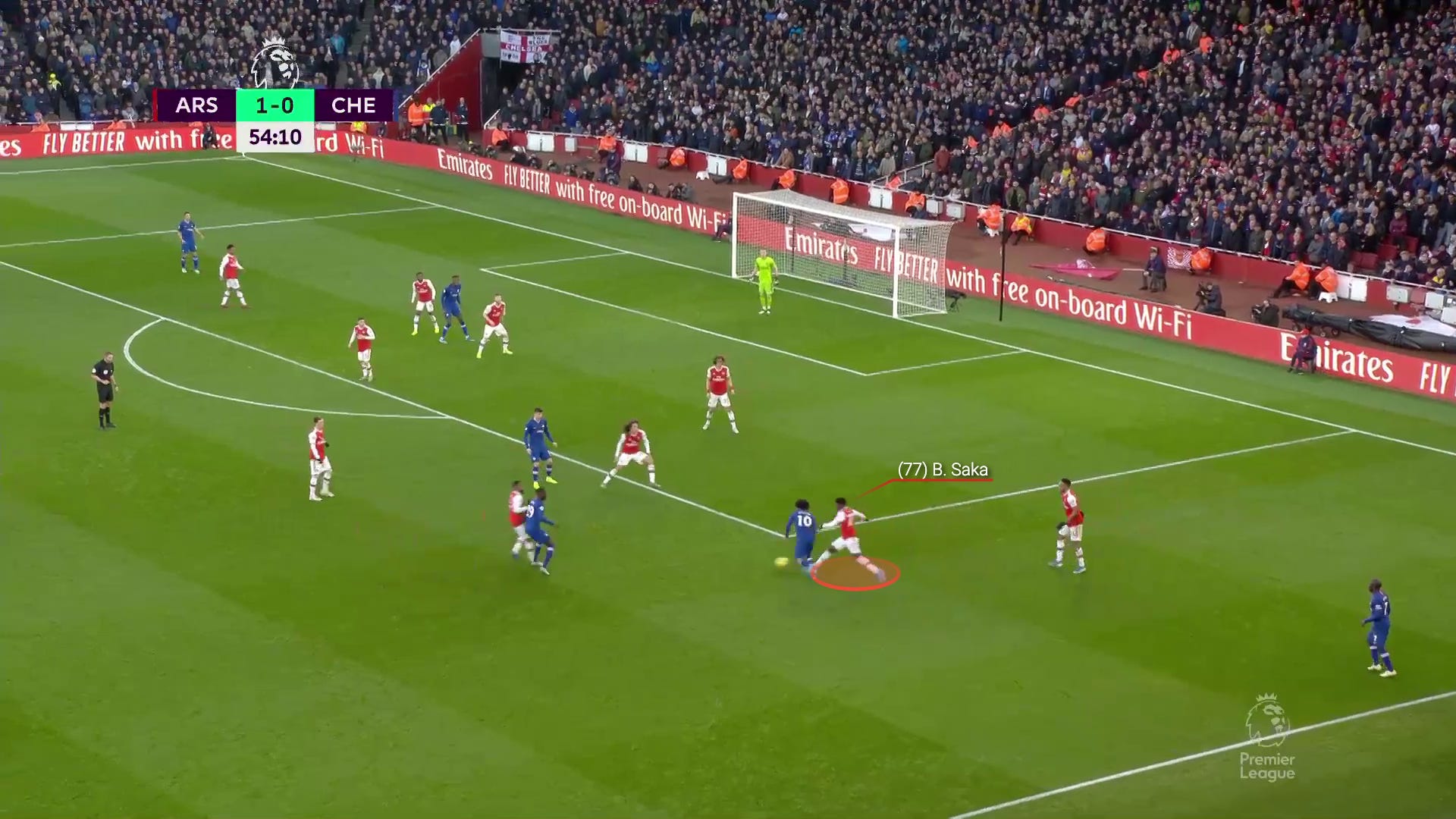

Facing Willian here, he leaned outside, and patiently waited for a move to be made. When Willian finally had him “beat,” Saka knew to expect a longer touch as he tried to get around. Timing it well, he poked it away:

As a winger, Saka counteracts this defensive option in a few ways.

The first is by simply not having many loose touches. When he’s in a situation like this, he’s almost dragging the ball along, touching the ball with every step, and opting to make control a higher priority than outright pace:

At higher speeds, his gait is different than many speedy wingers. His long shuffles turn into a glide, enabling a closeness with the ball:

As a defender, you’re taught not to take huge steps, ensuring you’re caught off-balance as little as possible. Perhaps it’s just a sense of projection for the sake of this article, but it does sure seem like Saka has almost adapted that shuffling to the attacking game.

All of this combines to make it really difficult to know when to step in on him. Together with some of that famed Premier League cynicism, defenders tend to get frustrated and take full whacks at his legs, as Silva did multiple times before waving the white flag:

Which brings us to the final step: the intentional, longer touch. We’ve all seen the clips of speedy attackers flicking the ball into space and sprinting past the defender.

When facing such a move, the natural impulse — ever-present in younger divisions — is to try to chase the ball and beat the attacker to it. Saka attempted to do that here while defending Antonio:

That’s not going to go so well. Not only does the attacker have the natural advantage of initiating the action, they are already at a full sprint.

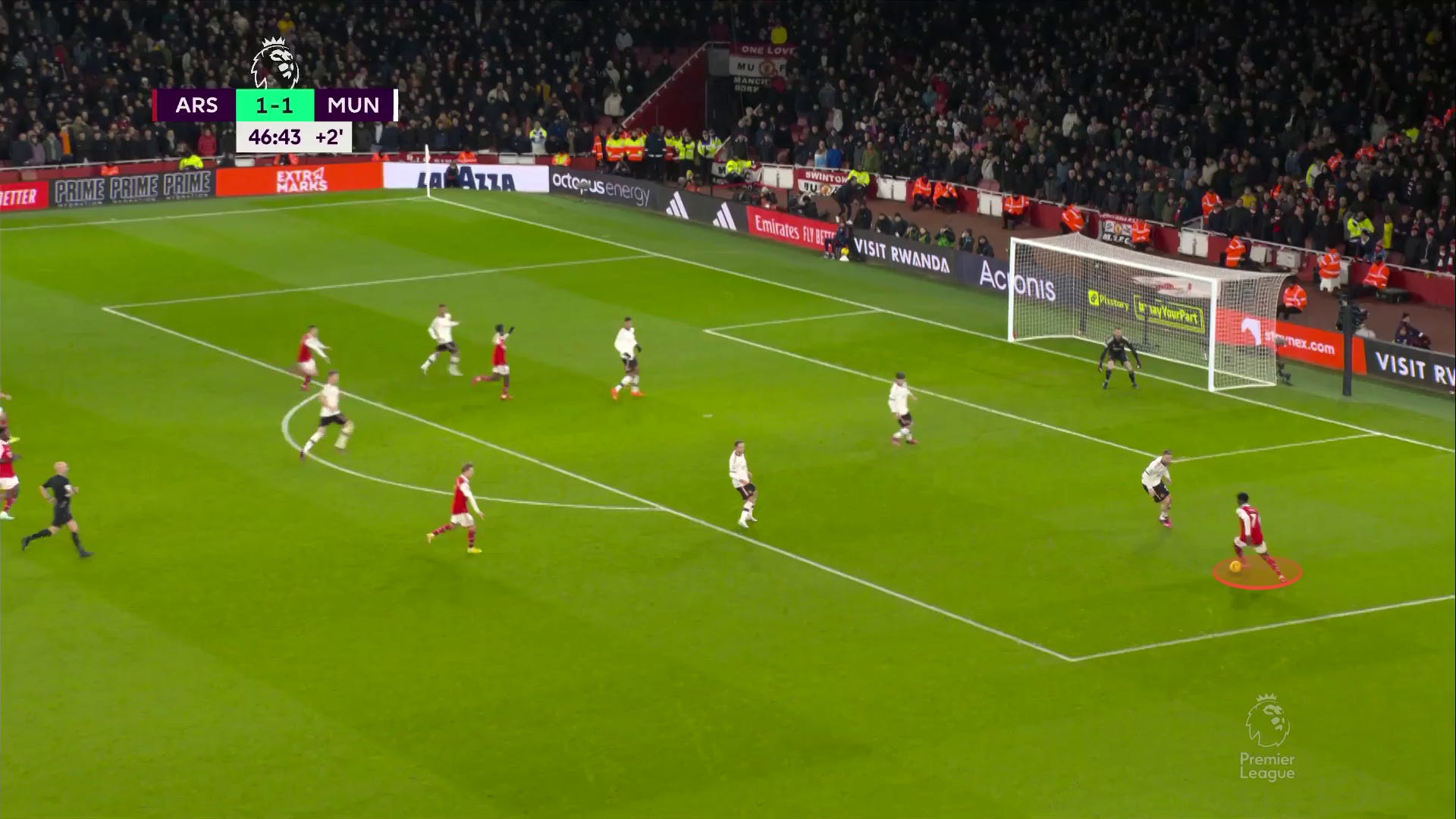

With training, one can learn to override this impulse. Gradually, as the #77 became the #7, Saka started improving in these situations.

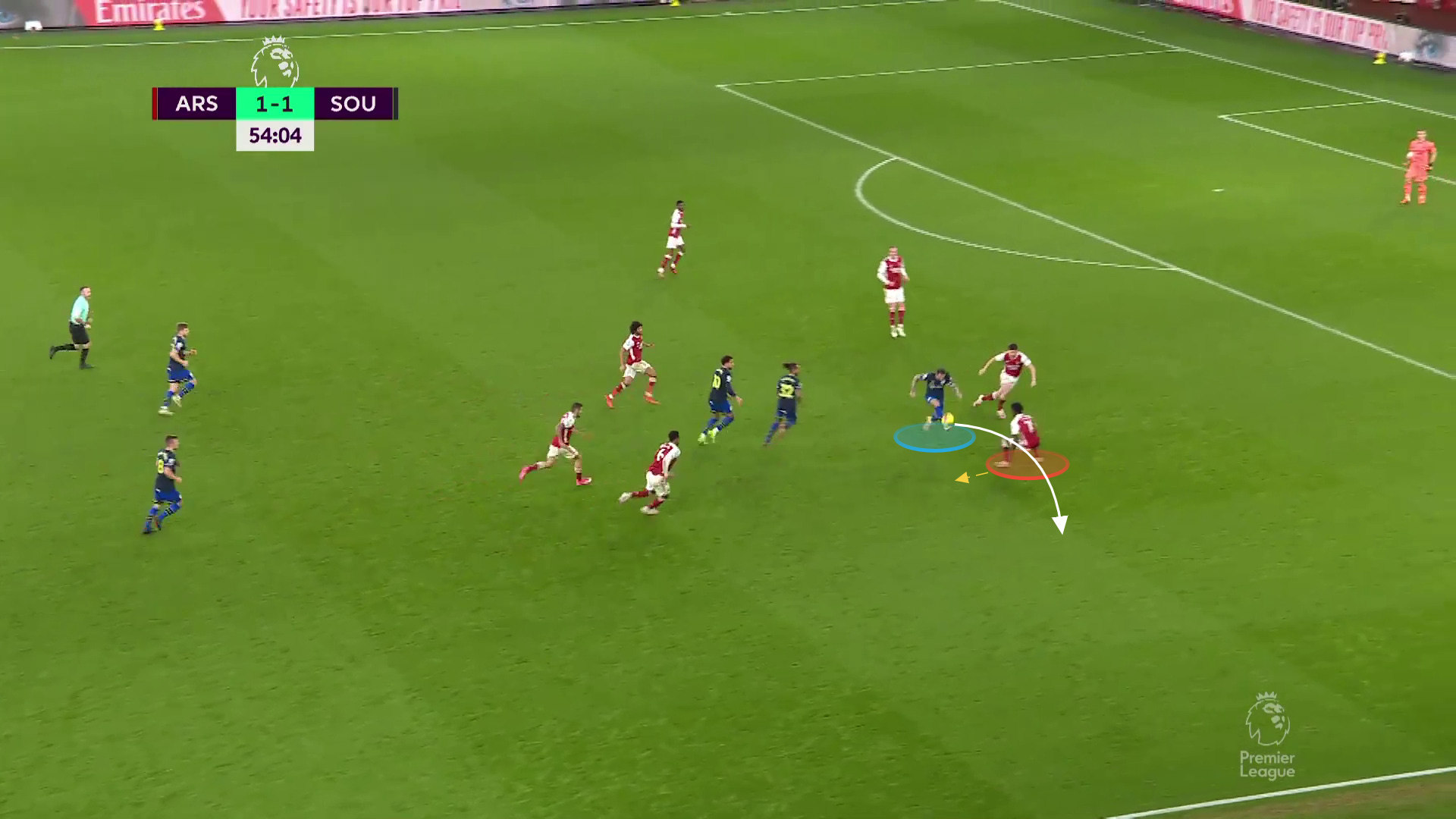

Here, Danny Ings tried to flick it into space so he could play attackers like Walcott through the middle. Instead of turning around and going after the ball, Saka went after the man:

Winning position first, he boxes him out from the ball, and fully interrupts the attack:

They called a foul, but fuck that.

The point here is that Saka has learned to adapt this skill to the attacking phase. Whenever it’s popped long, he looks to establish position first, like a defender, prior to securing it. Coach Paul McGuinness refers to this as “body as barrier,” and it’s something Messi always excelled at, often intentionally winding his dribbles directly in front of trailing opponents.

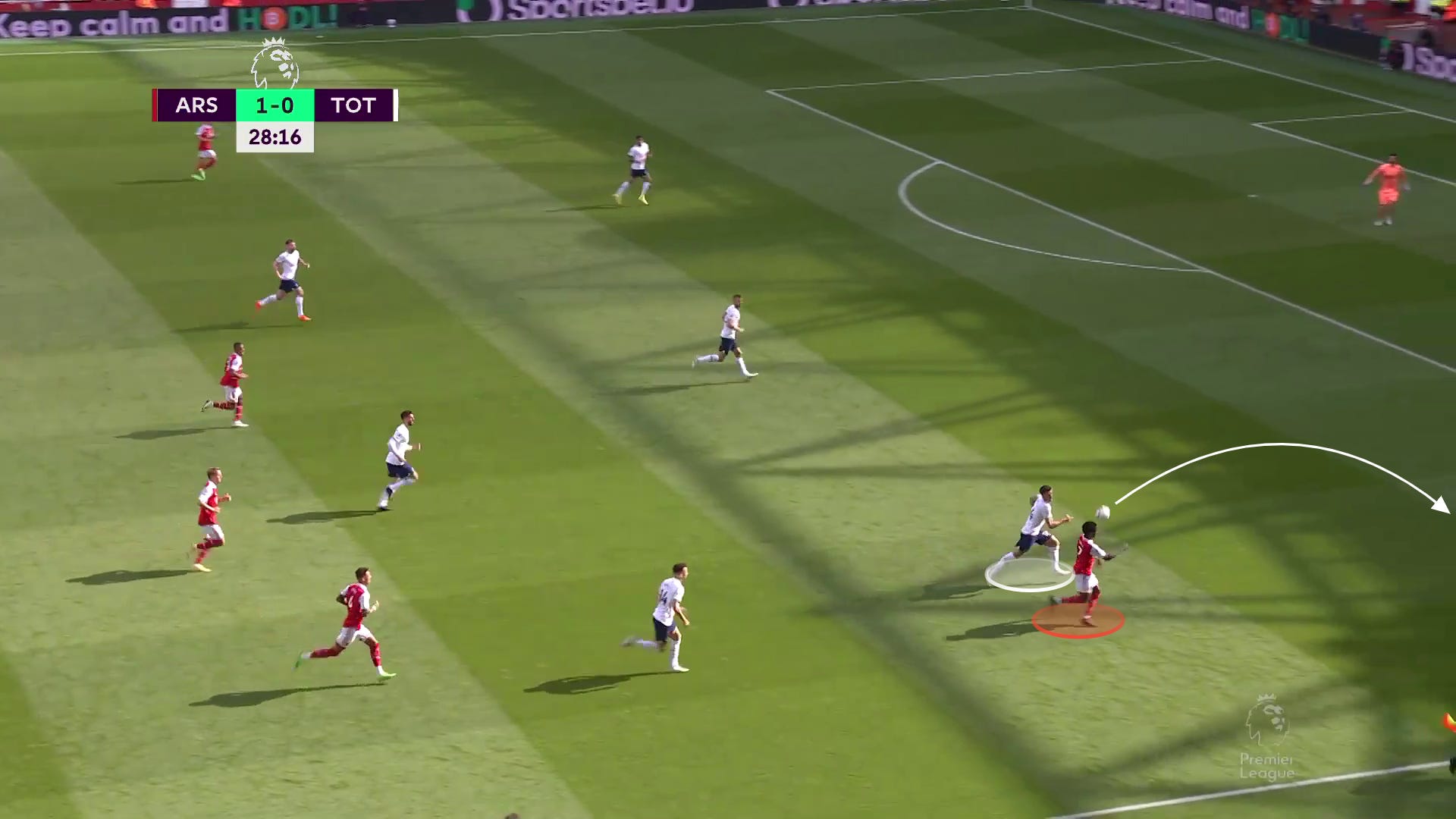

Here against Spurs, Saka accepts a long-ball from Ramsdale and pops it into the corner with his head. It’s now a race with Lenglet:

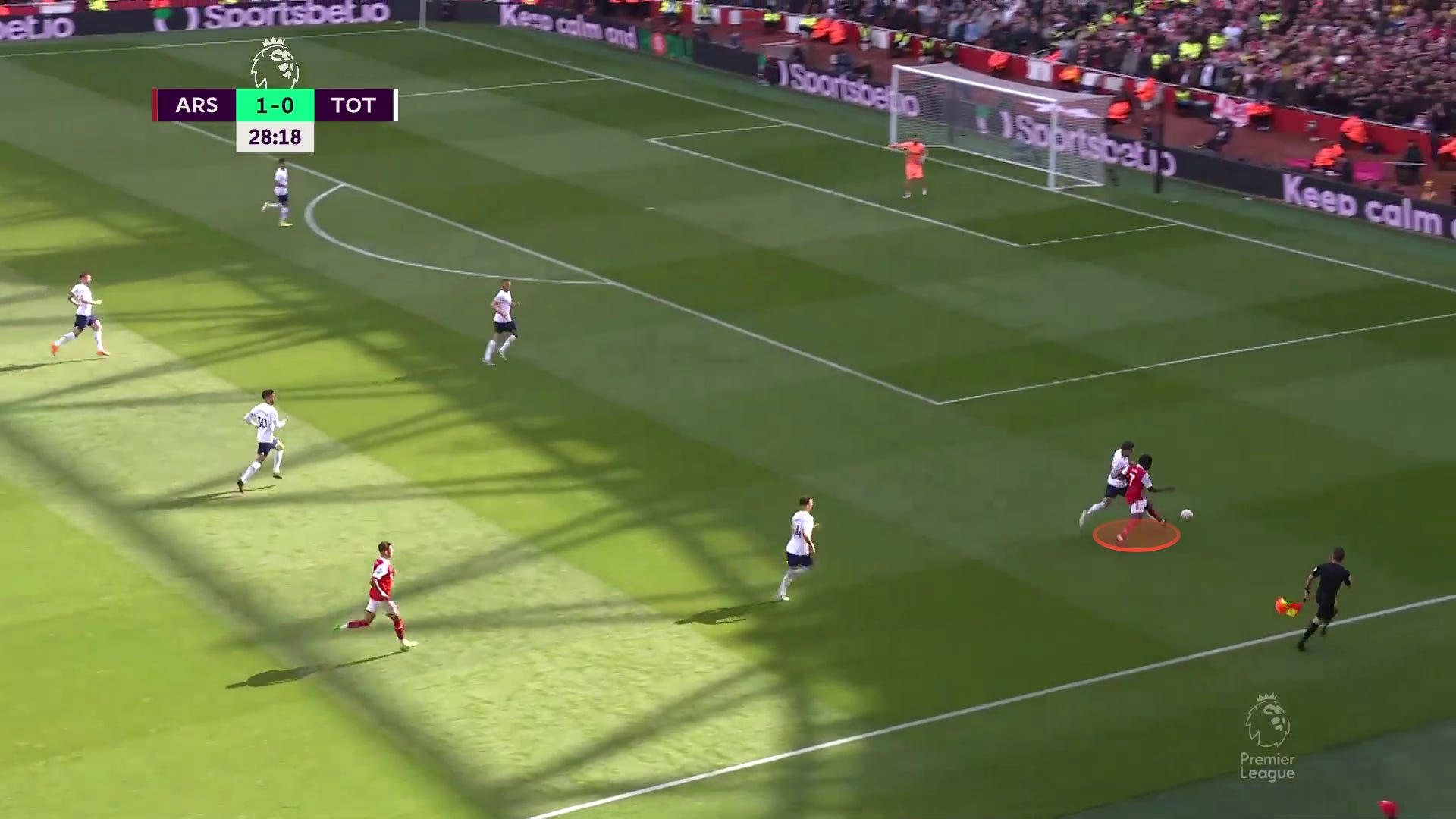

…and as always, his thoughts turn to gaining leverage, stepping in front of Lenglet’s run to establish position before securing it:

Or, you can look at the angle he takes when he’s corralling a loose ball:

Man first, ball second. A defender’s instinct brought up the pitch.

TL;DR

I shan’t overstate my findings. It’s nearly impossible to decouple the concept of “being excellent at exploiting full-backs” from “being a good winger,” and many of these qualities are those that a winger has to pick up in any case. In truth, Saka displayed many of these inclinations from the word “go.”

Said Ben Chilwell:

“I can’t believe he (Saka) played at left-back when he can do that ... An assist and a goal and it ultimately wins us the game. I am delighted for him.”

Still, Saka is bizarrely advanced in many ways — as a human being, above all — and there are still a few skills in which I suspect his experience as a defender has helped him advance to such heights, so quickly, as a winger. It was rewarding, for example, to observe the similar strategies that he and Salah use when fighting for the ball — and then remember Salah, too, played left-back in his younger years.

So, here are five of Saka’s skills that may be extra-refined thanks to his experiences further back:

Avoiding (or counteracting) the moments of maximum defensive leverage when receiving the ball

Giving the defender the smallest, lowest, most balanced target to try and push against

Pre-empting a defender’s leans and hand-checks with leans and hand-checks of his own

Showing “neutral intentions” when dribbling, until the defender shows imbalance

Fighting for position (instead of the ball itself) on long touches or loose balls by using his “body as a barrier”

As the teenage Saka once shared, his experience as a full-back helped him put wingers under the microscope, and vice versa. It helped him think about “what I like them to do and what I don’t like them to do.”

That empathy, so present in all his interactions, becomes a weapon on the pitch.

Those poor full-backs.

And a thank you to Reddit user r/NketiahPropagandist for floating this as a potential topic way back. It’s been on my list ever since, and I finally got around to it!