Use your head

How exactly Toney dominated Saliba in the air, and what can be done about it (plus a couple other dubious observations after Brentford)

I should have a City preview coming your way this week, but in the meantime, the Brentford game is still fresh in the mind, sadly. To hold you over, I thought I’d empty my notebook with some dubious observations from the 1-1 draw.

Let’s begin!

Flight of the Bumblebee

In aerial duels, it’s best to be both good and tall — but if you must choose one, be good.

The list of NBA career rebounding leaders is predictably filled with giants, but peppered throughout are those who remind us that height is not the end-all. As a 7x rebounding champion, Dennis Rodman made up for his relative lack of size with every trick in the book. He’s held court in entertaining detail about studying the number of rotations the ball would take after missed shots on a player-by-player basis, and analyzing the likely trajectories off the rim for various teammates. Here was one such time:

Whether it’s positioning, balance, technique, scouting, strength, focus, or the dark arts, it all comes into play eventually. The good ones utilize them all.

Both City transplants reinforce this lesson at Arsenal. The savvy longball muscling of Gabriel Jesus has been missed since the World Cup break, and Oleksandr Zinchenko has been winning aerial battles at a surprising 75% rate.

Meanwhile, at center-half, the twin towers can sometimes struggle to impose, despite some fun goals to their name. Helming positions that usually dominate the air, Saliba wins 54.4% of his battles in the air (24th percentile amongst CB’s), and Gabriel wins 48.9% (10th percentile).

These struggles came into 4K focus against Brentford. The Bees won 32/45 aerial battles (71.1%) in all, their highest win rate in any game this season.

More specifically, the struggles were against Ivan Toney. According to fb-ref, Toney won 12/14 (85.7%) of his aerial duels, also his highest number of the season.

Most specifically, Toney dominated Saliba— and did so in a particular spot on the pitch. Saliba ended the day 1 for 11, for a 9.1% success rate.

But… Saliba is tall, athletic, and generally composed. What gives?

Brentford’s overall approach wasn’t exactly a well-guarded secret. After discussing their likely defensive gameplan, here’s what I wrote before the game:

It's all about being aggressive and direct to generate efficient chances in attack. Raya is pretty ridiculous with the ball at his feet, and his pairing with Toney is potent: Toney seems to come down with everything. They just skip the middle phase of progression a lot, and come down with second balls if they don't get the first one. From there, Mbueno is smart/fast at finding complementary runs.

It’s easy to see why this is part of Thomas Frank’s strategy. For one, the Raya-to-Toney longball maximizes the strengths of both, and handshakes perfectly to Mbueno’s savviness at picking out angles on second balls. It also allows them to skip standard buildup, where they can look more ordinary.

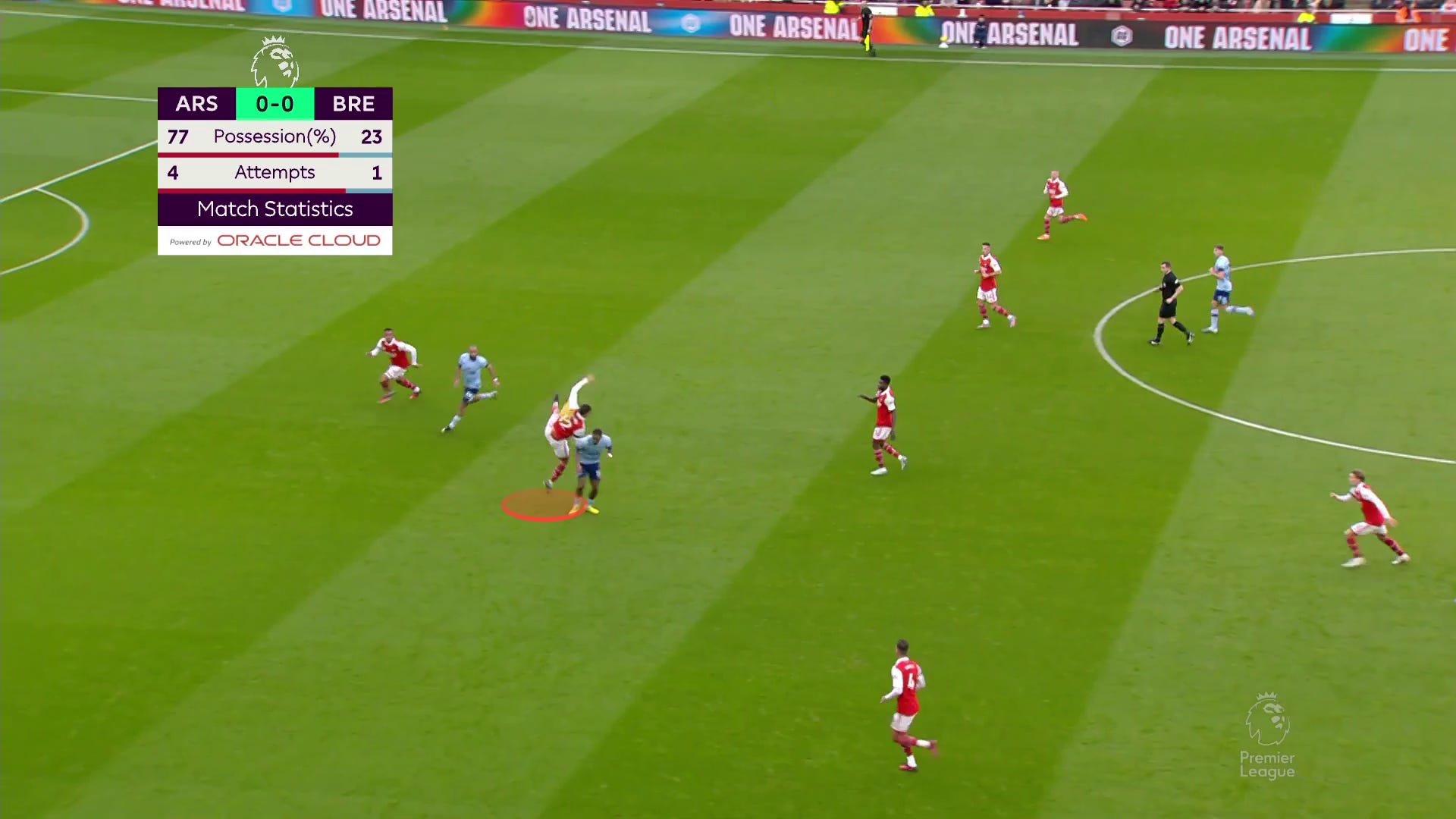

But there’s another reason why it’s part of Brentford’s gameplan, and it’s this: all aerial duels are not created equal. Corner routines are a beautiful chaos symphony unto themselves. Around the middle of the pitch, on the other hand, it’s often a more focused 1v1 battle, with a surrounding blanket of players looking for the second ball. As such, there are many advantages to the attacking team if they’re not too precious with possession. Let’s look at this screenshot of a ball coming in from Raya:

What built-in advantages do attackers like Toney have here?

They have preferred position on the ball: They are on the inside track.

They can make mistakes: The two players have different risk profiles. A mistake for the attacker means a bouncing ball in the midfield that may still be corralled by a teammate. A mistake for the defender may mean a goal.

They can launch off one foot: Depending on the run-up, it might be easier or more effective for a player to jump off one foot. This option is more readily available to the attacker, who can afford to lose balance in the air. A defender going down can quickly turn into a goal.

They are less likely to be called for fouls: I have no backing statistics for this, but it feels true, and saying something feels true without evidence is the kind of thing that gets you elected to public office these days, so I’m giving it a whirl. Vote Carpenter.

Despite it all, top center-backs use their size and positioning to whisk these attacks away without much pageantry. Let’s see where Saliba went wrong.

First, he played the ball, not the man. These longballs are of the true 1v1 variety, and as such, the objective is not to be the highest jumper on the pitch, or even win every individual duel—it’s to maximize leverage and position on one guy to make sure a good chance doesn’t get kicked off. (Outrun your friend, not the bear, etc.)

Looking back at the first half, there was a common theme in Saliba-vs-Toney aerial duels. Saliba’s failure, strangely enough, was in trying too hard to win the ball—without caring enough about Toney.

Early in the game, he ignored Toney, tracked the ball, and showed his cards by planting his feet for the jump:

Toney can then arrive a split-second later, jump off one foot to generate power into Saliba, win the header by flicking it to Mbeumo, and knock Saliba over in the process:

Toney was called for a foul, but I’m not sure he should have been.

It wasn’t long before Saliba did it again—jumping at the ball without first establishing position. Here he goes straight up without any drive from his back foot:

At the same time, Toney stays on the ground and leans towards the ball a bit, which is his right. This unsettles Saliba’s balance, and sends the big man flying again:

So how do you generate better position? You start by using your arms.

Speaking of arms, here’s a screenshot that made the rounds after the game:

Saliba was ultimately called for the foul here, which led to the set piece, which led to the uncalled offside, which led to the other uncalled offside, which led to the goal. Bullshit inception was successfully achieved, the grapes are still sour, but that’s ultimately a different post. Back to this.

This isn’t just about Toney looking for a foul. By drawing Saliba into him, Saliba can’t successfully use any real momentum (aside from a lean or nudge) to move Toney off his spot, and most importantly, he can’t use his arms to do so.

Ideally, the sequence may go like this:

Saliba broadly tracks the flight of the ball

He immediately uses his forearm in a “shield” position to unsettle the attacker and create as much space as he can

Then he backs up, plants his back foot, and jumps forward off both feet — timing the jump without excessive concern about being the first in the air

There are a million examples of Van Dijk doing this successfully over the years, and for everything else, he’s been keeping up his aerial dominance in this campaign (doing so at a 78.6% clip).

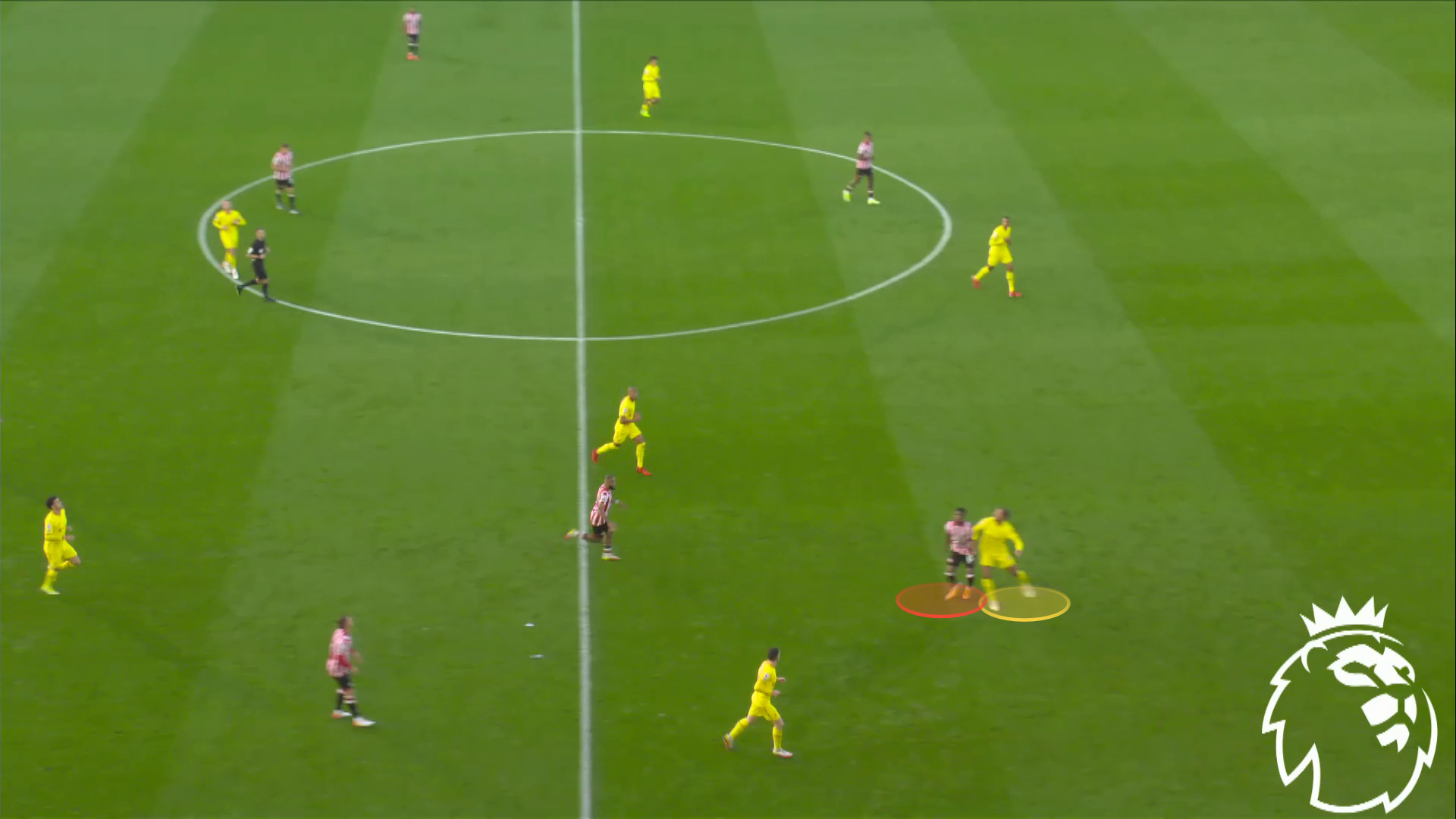

Here was the first example I dug up. Van Dijk and Onyeka are tracking a ball from the keeper to the touchline. It’s due to land in the yellow area:

…now that Van Dijk has a good appraisal of where it’s going, he turns his focus to his opponent. He changes direction to Onyeka, and gives him a shielding forearm to unsettle him and push him off the spot:

Then he cuts back to where the ball is moving towards. With the space he received by establishing position and shoving Onyeka off, he barely has to leave his feet to dispatch the header:

When he doesn’t have time to shove his opponent off the spot, he gets leverage with the shape of the jump itself.

This is a little blurry, but you can see how sharp the angle he takes when leaning forward to jump. He’s getting a lot of drive from his back foot:

…and that makes it very difficult for Richarlison to go up against. The momentum means the attacker basically has to hit the deck, instead of the other way around:

Brentford has three of the top six aerial winners in the league in Toney, Ben Mee, and Ethan Pinnock. Toney has a rugged genius for this kind of thing, and Saliba was not his first victim — though he may have been his most conclusive.

I’m an idiot, and I’m no coach, though I impersonate one for my son’s team (and for these articles). I’m sure the Arsenal trainers are working hard on this, as they should: it is one way in which our backline lags behind the likes of City and Newcastle. From my eyes, Saliba should concentrate less on winning the ball outright, and more on generating leverage against his man—which, funnily enough, should help him win the ball outright with more frequency. If he wins with his forearm and his base, the header will take care of itself. If it doesn’t, he’ll still be in good position to handle what happens next.

Schematically, it was probably a mistake to leave Tomiyasu on the bench in this one, and not just in hindsight. White had a solid game on Saturday and wasn’t ultimately the problem, but Tomiyasu may have presented the solution.

When they’re both “on,” the two have similar contributions, with minor differences. White is a little bit snappier and progressive, while Tomiyasu is world-elite in the air, particularly on these shoo-away longballs: he was 99th percentile at aerials won last year, with 2.57 per 90, and helped win the game against Liverpool by heading everything away. Toney wouldn’t ultimately have been his mark, but with Brentford only committing two forwards in most cases, I can still imagine Tomiyasu offering a lot of help in a game that was always likely to be decided in the air.

Brentford ≠ Everton

It was hard not to feel like the Brentford game was a continuation of the one against Everton the week before, in which a frustratingly disciplined team in a lowish block stymied the Arsenal attack and stripped them of their dynamism.

I’m here to say that we should be careful when conflating the two. Dare I say it, I’m here to offer hope.

Against Everton, Arsenal were pretty soundly outplayed. The muscular, packed midfield and double-winger defending turned Arsenal into a shell of its early-season self. Writing on Reddit afterwards, I said this:

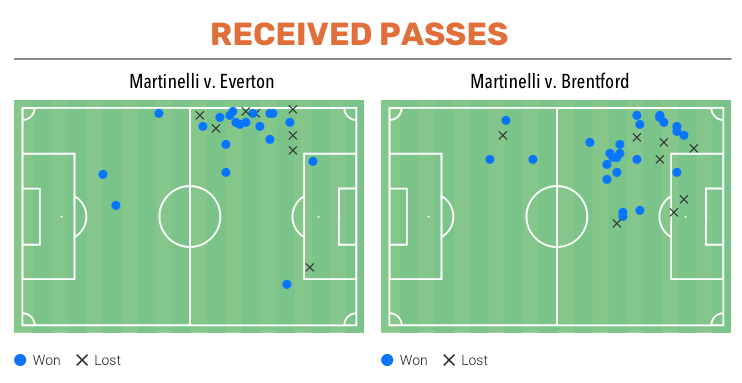

A lot of the rotations for Arsenal originate during build-up in the middle third: Eddie/Jesus will drop deep and somebody else will rotate centrally to cover, or Xhaka will go to the touchline and Martinelli will shade in, Martinelli will go on a dribbling expedition across zones, etc, etc. When a team like Everton shows no semblance of pressure in the middle third and just lets them build up unobstructed, those automatic rotations don’t happen: as a result, players are more likely to just park in their channels in the advanced third, which risks stagnation. I think this means players need to generate more manual, individual, non-automated rotations like Zinchenko/Jesus offer: Martinelli taking up spots in the half-space or middle simply because, fuck it, I’m doing that this time — and teammates, you better adjust as a result.

The squad stayed the same against Brentford, but the story changed. Arteta clearly pushed his players to get out of their respective channels and play with a lot more expression, and Martinelli answered the call.

You can see this in his received passes, which were less isolated and more central:

You can also see it in his own passes, which show much more dialogue with the full pitch:

And you can see it in the tape. If the objective is to appease me, a humble and stupid independent football writer, these freelancing cross-zone cuts are the way to do it. This one nearly turned into a goal for Martinelli:

From there, we talked about how Xhaka excels while exploiting numerical advantages, which are more likely to be found against top sides who are more forward in their play:

So there’s two options to unlock that spot when facing a parked bus: send numbers to the left (have Gabriel/Ødegaard/Eddie/etc join the triangle, move to a 6-high with the full-back, etc) or… play a dribbler.

Arsenal didn’t play a dribbler until late, but there was a lot more presence over there by the likes of Gabriel and Ø. In another moment that was designed to make me happy, Saka joined the left channel to turn the team into a 6-high. He makes a cut and gets a near-post shot off:

How’d it all work out? In terms of underlying stats, pretty well. Overall, they notched:

45 shot-creating actions (the two offensive actions leading directly to a shot). Highest of the year.

18 key passes. Second-highest this year.

26 passes into the penalty area. Easily the highest this year.

Won 13 of 21 take-ons (61.9%). Third-highest of the year.

The problem was pretty narrow: shot quality, and overall variance. Thanks to some hopeful Zinchenko balls (which are all good, but perhaps not at the quantity he showed on Saturday), Arsenal had a low shot on target % (7 of 23) and averaged their furthest shot distance of the year (19.6 yards).

They still managed a higher xG this time around than their earlier 3-0 drubbing of the same squad. This is how it goes, sometimes. Was their final product excellent? Not especially. Was it a noticeable improvement from a stagnant, listless attack that didn’t seem to have any answers against Everton? Absolutely.

Saka is Switched-On

As we covered when we talked about Xhaka, there are two types of advantages to exploit: quantitative (I have more numbers than you) and qualitative (my player is better than yours). Xhaka is unlikely to roast somebody based on pure technical burst, so is best when playing with numbers. On the other hand, Brentford was happy to isolate Toney on Saliba based on the well-founded belief that Toney was better at coming down with balls from the air.

On the Arsenal right, a story repeats itself almost every week. Saka is entering World XI territory where he is never defended alone: he is generally marked by both a defender and a wide midfielder (or winger).

And almost every time, it’s unlikely that both players could match up well against him in a 1v1: think Shaw (good) and Eriksen (bad). In this case, Rico Henry matches up about as well as you can: smart, active, fast as hell. On the other hand, the wide midfielder was Mathias Jensen, who is an excellent player in his own right, but lacks the burst of a Saka.

You remember what happened next. Saka accepts the ball on the touchline with Henry on him. White immediate starts the chugga-chugga overlap, forcing a switch:

With Henry following White into the box, Saka is now isolated on Jensen. Saka plays a 1-2 to Ødegaard and immediately cuts, leaving the slower Jensen in his wake:

Henry may have had the recovery speed to bother Saka, Jensen doesn’t. In fact, he falls on his ass as Saka delivers the cross to put Arsenal up 1-0:

It takes a village to effectively guard Saka. Some villagers struggle more than others, and when that’s the case, Arsenal should keep doing everything in their power to get them isolated.

OK, that’s it for now. Like I said, I hope to have a City preview for you if the schedule allows.

Until then, be good, and happy grilling.

🔥

Amazing write-up!