What ails Arsenal

An enormous excavation after a deflating end to the year, looking at tactical evolutions, attacking dynamics, luck/variance, the wingers, both boxes, and what must change to reach the heights we seek

“Our dilemma is that we hate change and love it at the same time; what we really want is for things to remain the same but get better.” — Sydney J. Harris

How quickly things shift.

The last time we spoke, we were recapping Brighton, which wasn’t just one of Arsenal’s best performances of the season, but the best out-of-possession displays I’ve seen by any team in some time. Things were clicking. Patient investments were paying off.

We’ve had three games in the period since. In the first, the team delivered an inspired, determined performance at Anfield. It ultimately ended in a draw, which was probably about fair on the merits. Whatever the case, Arsenal were top-of-the-table at Christmas.

By New Years, they’d accumulated two wrenching losses in quick succession and dropped to fourth. The West Ham game was created by an evil genius (Moyes?) to be as absolutely-fucking-annoying as humanly possible, provoking difficult questions. Questions like “no?” and “why?”

The Fulham match at Craven Cottage — after a Thursday-to-Sunday turnaround — was, well, flat-out terrible.

Santa has long since packed up his shit and evaporated over the horizon line.

The joy has ended. The recriminations have begun.

👉 In pursuit of the easy-to-understand

We love straightforward answers. And in truth, football often provides us with them.

I’ll start. Goals are good. Being large and fast is a nice advantage. The more of the ball you have, generally speaking, the better off you’ll be.

It applies to players, too. For someone like Trent Alexander-Arnold, who has withstood endless and disproportionate critique throughout his career, I’ve often wondered if the average 8-year-old may scout him better than the average adult fan. He probably kicks balls better than anyone alive. Yes, that is pretty much the sport. Yes, that makes him one of the best players in the world. End of.

In fact, Klopp’s entire recruitment strategy of late seems to follow that course. “Beat it, nerds. Just get me a bunch of players who run a lot and kick the ball real good, and I’ll figure out the rest later.” And guess what? It’s working. There would be something refreshing about that if it did not potentially come at our expense.

Between these clear truths, though, there is fog.

Which is probably why all my posts are so long.

🤨 So, what is wrong?

There is a simple, inconvenient truth about Arsenal’s season, blinking like a neon sign. Arsenal are not creating enough open play goals.

According to Opta, Arsenal are 7th in open play xG (with 25.17), and 13th in total open play goals (with 19) at the time of writing this. Not great, Bob.

But while we may try to conflate this all into one coherent story — the team plays slow, the new additions aren’t working, the dynamics are off, Xhakkaaaaaaaaa — I would argue that there have been multiple stages in the team’s evolution, all of which provide helpful context.

To help us understand the sharpest schism, I pulled data before and after a particularly meaningful change. This will add context to the rest of the discussion, as I think it is one of the central stories of the season.

Let’s talk about how it came about.

♟ How the dynamics have evolved

In the earliest portions of the season, we saw Arteta using his fresh personnel to devise new ways of breaking down the low block. In what I’d call a 3-4-3 diamond, we saw Timber and Tomiyasu out wide at LB/LCB, Partey inverting from the right, and an overstocked midfield. Possession and control were paramount, and some new tricks were sought.

But reality would interrupt this tinkering.

Timber injured his ACL in the first game. Jesus would have two separate periods of absence. Partey has been out for most of the year.

At various times, Arsenal have been without Ødegaard, Tomiyasu, Jorginho, Elneny, Vieira, ESR, Trossard, and Martinelli. White has been playing through an “uncomfortable long-term issue.” Even Saka was out for the Man City game, and has been reportedly nursing an Achilles problem for a long while now.

Injuries seem to be spiking across the sport. Many teams are facing similar situations, and some are in much worse shape, so there’s no crying on the yacht. Just kidding, I still cry for Timber, though I do it from my basement.

Still, from this view, it’s easy to see how this may impact your best-laid plans.

In a related note, I think something may be missing from our discussion about Arsenal tactics.

It’s commonly accepted that Arteta has put an increasing priority on possession and control this year, pinning the opponent back and risking less, perhaps as a way of “de-variancing” games and lowering the chance of the clunkier goal concessions we saw last year.

In many ways, that has been a hugely successful enterprise. Arsenal have the best xGA (expected goals against) in the Premier League, and for most of the season, have looked like one of the best defensive sides in the world. Declan Rice is sublime in a way that is self-evident, but Havertz has also been a lankier, ever-present destroyer as well. He’s tackling and winning duels at a much higher rate than the midfielders of yore.

Possession — at least in terms of quantity — is also going swimmingly. Arsenal are first in progressive passes, near the top in possession %, and tops in “field-tilt” (calculated as “ball possession percentage calculated for touches completed only in final thirds”).

All of this is related. The more secure the possession, the more disciplined and locked-in the positioning, the better the gegenpress can be in the rare(r) times when the ball is lost. All of the zones are naturally filled.

Look at how the team is set up with the ball here. As soon as it’s lost (when a Saliba pass is intercepted), Rice is well-situated to jump, take it back, and create an attack the other way.

So what gives?

🥵 Hard-won lessons

One must only look at Liverpool last year, or Newcastle and Tottenham this year, to see how a playing philosophy might affect squad depth, and vice versa.

Last year, Liverpool sought to press to the hilt, but with an aging list of players and spotty reinforcements, injuries piled up, lanes opened everywhere, and goals leaked in droves. This summer, they got four younger, more athletically fit midfielders, and suddenly everything is fine again.

Newcastle and Tottenham may currently be experiencing the dark side of their own heavy metal tactics. Newcastle’s game model, built on out-running and out-sizing the opposition, has met a worthy foe: not an individual opponent, but the pressure of a jam-packed schedule. The majority of their starters have missed significant time. They got bounced from the Champions League. They’ve only won 1 of their last 8 games, and their swarming out-of-possession dominance is no more. Such rabid intensity is hard to keep up indiscriminately.

(Edit: as I go to hit post, I see the great Liam Tharme has published an examination into this very topic with Newcastle. Great stuff, and it covers a bit of what we see here).

As of November, according to Sky Sports, Tottenham had led the league in sprints by a margin, and have been dropping like flies in the meantime.

Luck and variance do play a big part here, of course, and fitness is a complex topic. But Arsenal learned some of these hard lessons last year. While they over-performed their underlying metrics, and were desperately fortunate with injuries for much of the year, reality and burnout eventually hit — hard. Like you, I have rather visceral memories of Rob Holding trying to match strides with Erling Haaland, a hobbled Thomas Partey getting burnt by Kevin de Bruyne, and others (like Xhaka) trying in vain to catch up to all the action.

The truth is that you and I arrange little dots on a screen, confidently pontificating about what lineup and tactic should be used when, but we do so in the aforementioned fog. For any manager, there are much more practical considerations. How do players jive together? Who is nursing a knock? Who earned it in training?

🚑 The battle of attrition

Which brings us to my current point. The Premier League is a battle of attrition, and I’d humbly suggest that while many of Arteta’s early-season moves have indeed been borne out of a desire for solidity and control, there may have been another, more practical objective in play as well: the desire to play the long game, better supporting a thinning squad’s fitness for the full campaign, lest the previous season’s travails be repeated.

One way to do that is through steady, advanced possession. By dribbling less and passing around the attacking third more, the opponent has to move around a lot, but you have to run at lower rates. After all, the ball is in transit, not you. This is what I mean when I say that a playing style can affect squad depth and vice versa.

Some numbers from Opta show us how the directness of the dribbles has changed, despite the midfield getting younger and burstier.

Take-on attempts down (19.8 to 18.6)

Successful take-ons down (9.24 to 7.55)

Take-on success % down (46.7% to 40.6%)

Some numbers from Wyscout help us illustrate how the tempo has changed.

Passes per minute of possession: 16.43 this year / 17.21 last year (i.e., slower circulation)

Passes per possession: 5.9 this year / 5.36 last year (i.e., longer possession sequences)

The hope, then, would be that a team with such possessional dominance, not to mention a newly-fortified defensive spine that may be the best in the world, could generate the requisite amount of stranglehold to dominate games, even if the passing or dribbling wasn’t as reliably intense or direct.

Then, through set pieces, individual winger quality, and Kai poaching, enough attacking threat could be generated to win a whole lot — while balancing the European schedule, and without expending all of the team’s fitness too early. The team can still go all-out in sprinting, but in moments. Trophies could be secured while other squads have higher rates of exhaustion or injury.

The first part of that gambit has proven true. The second part has also loomed enormous. Arsenal is joint-top in the league in set play goals, and have over-performed their xG there by a healthy margin.

Arsenal also lead the league in generating penalties, going a perfect 6/6 from the spot.

All of this hopefully illustrates how Arsenal were able to remain top of the table at Christmas despite being 13th in open play goals.

Eventually, though, something had to change.

🙏 Inflection points and changes

A few warning signs were building.

The Tottenham draw felt more toothless than it could have. The 2-1 loss at Lens was humbling, and — along with this last Fulham game — remains one of the two occasions all season that I’d confidently say Arsenal were truly outplayed. Some others fall into the gray area.

But a beleaguering 2-2 draw at Stamford Bridge felt like the first sign that something must change. Though all the metrics would say that Chelsea were stifled but fortunate, the Arsenal front-3 was back in action, and nonetheless stalled for desperately long periods.

Ødegaard was fully shadow-marked out of the proceedings in an approach that was gaining popularity with opponents. The wingers were doubled, fouled, and mostly restrained. Zinchenko was yanked at half after getting burned by Raheem Sterling. It took some late heroics by Rice, Havertz, Saka, and Trossard to save the draw.

(As a side note, we do not seem to have a great relationship with driving rain.)

Thus began the first change.

Tomiyasu took over at the left-back, showing a much more freewheeling version of his game while adding to the defensive solidity we’ve come to know. The early returns were promising. They were also a lot of fun.

But there’s a corollary to that, one that will keep coming up. That role — as a left-8 target man, floating all the way up next to the striker, then doubling all the way back to the LB — is incredibly taxing. By upping the attacking pressure, Arteta also upped the pressure on player fitness.

This tactic carried Arsenal through a transitional period. The Tomiyasu change did indeed work, but then Ødegaard went out injured and back again.

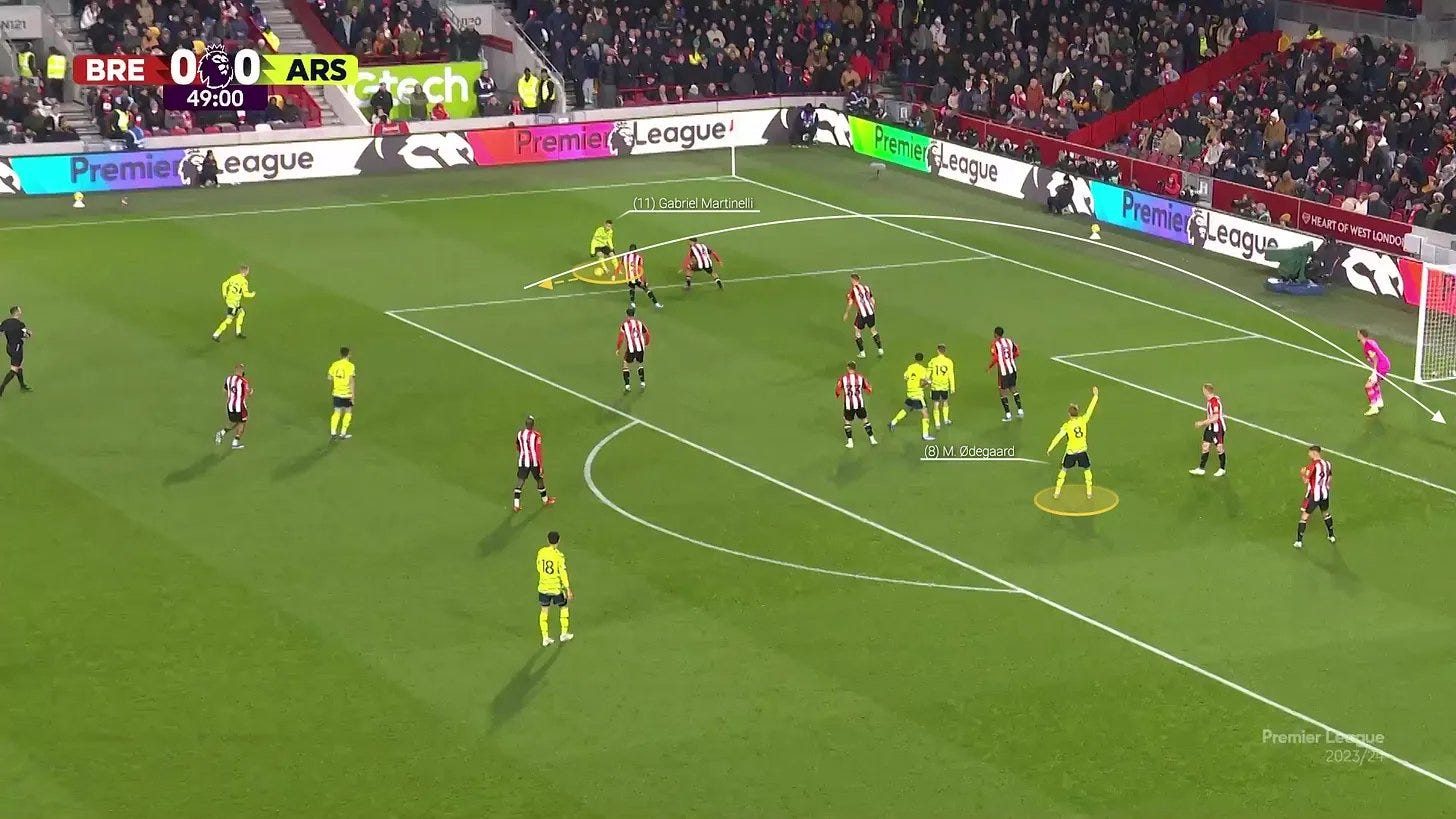

The Brentford game felt like the second inflection point. Though Arteta went with an attack-centric lineup, featuring Zinchenko at left-back and Trossard at left-8, things felt relatively stale again. More heroics were required, and Havertz delivered with a winner in the 88th minute.

It was time for the big change.

It delivered immediate results. Though it was demoed a little bit earlier, the real deployment of this strategy can be easily seen in blue dots — first against Lens, then against Wolves in the league.

Ødegaard was to untie himself from the right half-space, dropping and floating throughout as a connector and secondary controller.

In gif form, here is the most simplistic way to see it. Instead of being “parked” on the front-line, like he was when facing Chelsea, here is Ødegaard dropping into the first line and dictating play like an orchestrator.

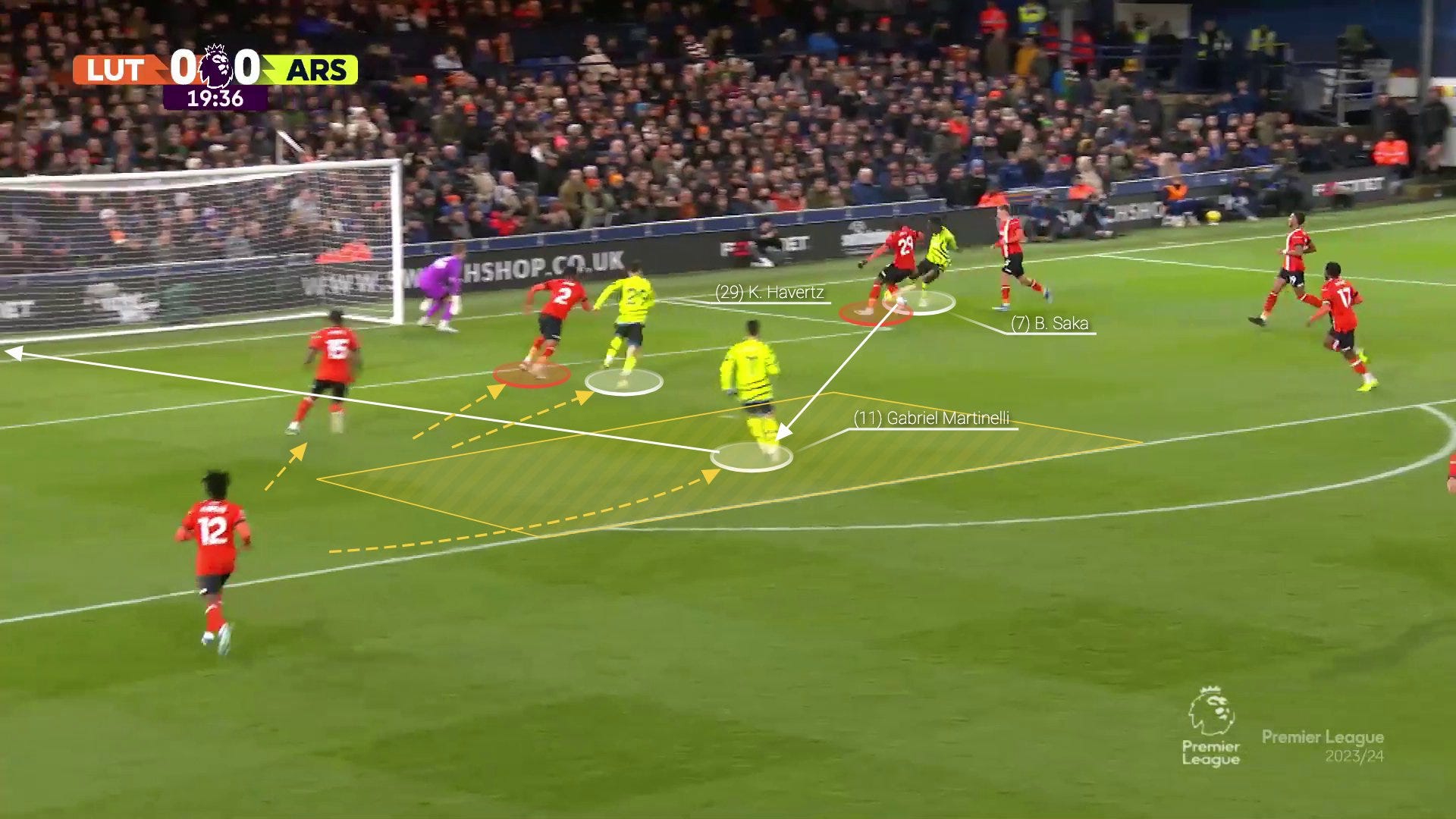

This tweak almost instantaneously contributed to better, more free-flowing play. Within six minutes of its league reintroduction, the looser rotations created this goal.

At 12’, Martinelli crashed a zone that Ødegaard would typically occupy. It led to a series of untethered movements that resulted in a goal by the man himself.

I am now going to post one of his passes from this new role against Brighton, just because it’s my newsletter, and I can do what I want. Look who is in the half-space, and look who is cleared to join a little more centrally.

This change unlocked something crucial in the underlying dynamics. Jorginho went back to the bench, Jesus played free and clear, Rice was patrolling the entire middle and increasingly supported in the build-up, and Havertz could lurch even further forward (and bring the ball down when Raya went long).

📈 The results of the shift

This all led to a 6-0 win against Lens in its first showing during this run. In the follow-up against Wolves, Ødegaard completed the most passes of his senior club career in any competition (87).

And as we saw in the graphic earlier, this change has had the following effects, even including the Fulham slog, which didn’t really follow these changes:

+10.44 live-ball shot-creating actions per game

+3.94 key passes per game

+13.69 progressive passes per game

+5.35 shots per game

+.56 non-penalty xG per game

It has been an extraordinarily positive change, at least in an underlying sense. Ødegaard was let down by his finishers against West Ham, but I’m not sure I’ve ever seen him look more complete or better.

There are a few trade-offs worth talking about, however.

In that game against Luton, the attacking force looked relentless and effective. The fluid build-up was fun and interesting; the Jesus/Havertz partnership blossomed; Martinelli rotated centrally, and scored.

But the reality is that with liquid build-ups like this, love it as I do, there’s a slightly higher chance of getting caught out on a ball loss. Because so many players are transitioning between zones, there’s a good chance that lanes open in the event of a Luton dispossession. They wound up with three goals on the evening.

These gaps are what Arteta sought to avoid with the gameplan at Anfield.

💭 Some thoughts after Anfield

Right after the best-in-show Brighton pressing performance, Arteta decided to tone it down at Anfield, sitting back in a more compact, disciplined block — and then launching some of the most direct, bouncy attacks of the season.

On the day, Arsenal had 100 fewer back/lateral passes, a lower line, a higher long pass percentage, and more low losses than usual. Arsenal (rightly) sought to take on Liverpool directly on the dribble. In the end, I felt the players on both sides largely did incredible — with some notes on ours that you probably remember. Especially after seeing their recent exploits, we shouldn’t shake a stick at holding Liverpool to their fewest shots, lowest pass percentage, fewest key passes, and lowest xG at Anfield.

But I also felt Arteta made a couple (relatively marginal) tactical missteps in that one.

For one, Arsenal had just shown Brighton that it could mount the most disciplined press imaginable, and, risks and all, I would have loved to have seen it turned to 11 against Liverpool, who can play a little loose, and were coming off a quick turnaround (whereas Arsenal got a week to rest and prepare). Scary to do at Anfield? Sure. But we have Declan Rice.

For another, Arteta had previously made aggressive affordances to compensate for the presences of Salah and Alexander-Arnold; he didn’t do that here. Gabriel could have swung more aggressively wide, as he has previously, keeping Zinchenko off of Salah Island, and Alexander-Arnold could have been given less time to deliver from the back-line. Their combined goal felt like the most predictable goal possible, and I don’t like conceding predictable goals. I would have preferred the route of over-compensating and making other players win it.

In all, I felt it was a question of identity, and the tactical makeup of the game turned it into one based on transitional moments and individual brilliance, instead of relentless pinning and suffocation. That naturally tilts it into the balance of Liverpool.

This was a no-doubter. Fucking Salah.

But anything I’ve mentioned here felt confined to this game, and the performance was nonetheless endearing.

💸 The price of intensity

The other, broader issue with the updated style of playing is separate from the Liverpool game. It is this: the Ødegaard role has added two more players to the list of those with an immense physical burden placed upon them.

The following are taxed as always.

Being a winger at Arsenal is draining. Constantly on-ball, constantly doubled, constantly fouled, but expected to get all the way back whenever the other team has the ball.

Ben White has previously said this about Arteta: “To play full-back for him, you've got to be a centre mid, a centre-back, a winger, a No 10.” In late-October, he led the league in overlaps. In November, he led the team in sprints. He can often be tasked with being the furthest player forward (on an overlap), one of the first three back (as a wide CB), and a midfield counter-presser. It’s a lot. He tricked us into believing it’s normal. It’s no wonder he’s dialed back his responsibilities and is nursing an injury.

The following are more taxed of late.

Ødegaard had 114 total actions against West Ham — including 82 passes, 25 duels, 7 recoveries, 14 dribbles, the most touches in attacking pen in his career (11), 9 completions into penalty area, and 5 shot assists, all while being hounded by Álvarez. Can he reasonably be expected to do this every time out?

With Ødegaard freer and the double-DM pivot not used of late, Declan Rice has had an increased, and often-lonely portfolio as a central patroller. In November, he was our furthest-running player, and I’d guess that number has only gone up.

The impacts of this trade-off — more intensity for better attacking dynamics — have been increasingly felt of late.

Arsenal are still the only team to beat PSV this year. In his post-mortem, PSV’s coach, Peter Bosz, said he learned something from his opponent.

“Afterwards, I thought, ‘We played pretty well… but we lost 4-0?’ In the build-up, we did well and we had our position game, but as soon as we got to their box it was over. How is that possible?”

“Me and my coaches studied them. What is it that they do differently to us? The answer is that they are outstanding in the opposition box but also their own. They get a lot of players behind the ball as soon as possible. They do it with 10 or 11 but we only did it with six or seven and then the distances are bigger. It’s the transition.

“We showed the players and, in the games after, we started doing it with 10 or 11 like Arsenal, staying compact in attack and defence.”

That, indeed, has been a constant feature of the Arsenal approach. When the team has to get back, everybody gets back.

But in the lead-up to West Ham’s second goal, that didn’t happen. Jesus had been tackled in the box, and was slow to regroup. Saka was just exhausted and walked.

In truth, I’m not mad about it. Superstars deserve a break every so often. But Bowen and Emerson easily generated the corner, and the game was all but sealed.

Fulham, I think it’s important to note, did not share a lot in common with previous performances, apart from the lack of goals. It was tired and sloppy in a conclusive way that felt unique on the year. Arteta was mad, and so were all of us.

“If you don’t (have) consistency of momentum, you don’t have threat in the final third and you concede two goals like we did today, (and then) it’s very difficult to win the game. We didn’t deserve to win the game, that’s very clear and simple … What happened today cannot happen again, because if you do that we will never have the chance to be where we want to be.”

For one of the first times all year, Arsenal couldn’t really close down on the press.

And instead of deploying Ødegaard in his newer, more effective, role, Arteta kept him high — as he did in the early-season.

He dropped here and there, but given all his recent exploits, this had to be about managing his workload on a short turnaround. Meanwhile, two low-touch poachers stood next to each other up front. What resulted was a game with early-season dynamics, but with none of the kind luck and set piece dominance — plus, newfound exhaustion and later-season shooting woes.

That is not a good cocktail.

Which brings us to the biggest factor of late.

😤 Problems at goal

Football may be the beautiful game, but it is also the most infuriating.

At the very moment that Arsenal improved their attacking dynamics, they lost their shooting boots. This couldn’t be better typified than by the 2-0 loss against West Ham, in which Arsenal led 30-6 on shots and 2.77-0.63 on non-penalty XG.

Others may decry this as a lack of luck, and sure, there’s truth to that, but I’m also traditional in this sense. Kicking the ball in the net is the game. As long as you don’t get fucked over by some grave injustice or inane refereeing decision — which is no given, certainly, and may have happened with another inconclusive camera check — I think the scoreline usually carries an element of fairness to it, no matter who had more shots taken or field tilt. It’s about kicking the ball in the net.

But still, the geeky stuff can be helpful context in such a messy, high-variance competition. And that seems especially applicable here.

Earlier, you saw a table that showed this recent period of Arsenal dynamics has resulted in 10 more shot-creating actions per game, ~4 more key passes, 13 more progressive passes, 5 more shots, and an increase of npxG of +0.56. This, naturally, has led to a drop in Arsenal goals, and a proportionate rise in the goals of the opposition.

Kill me. What’s going on?

Arsenal are just missing their shots. Here are some stats for you, courtesy of Opta.

Arsenal have marginally more shots than last year (15.9 to 15.5). They also have more shot-creating actions (29.4 to 27.5).

Arsenal lead the league in touches in the attacking pen (36.1).

Overall touches are up from 681.8 to 710.7.

Shots on target are down slightly, from 32.9% to 30.7%.

…and here’s the big one:

Post-shot expected goals on target (psXG/SoT) — which is a post-shot model, loosely measuring the quality of shot the opposition keeper faces — is now 17th in the league (0.27). Last year, Arsenal ranked first (0.33).

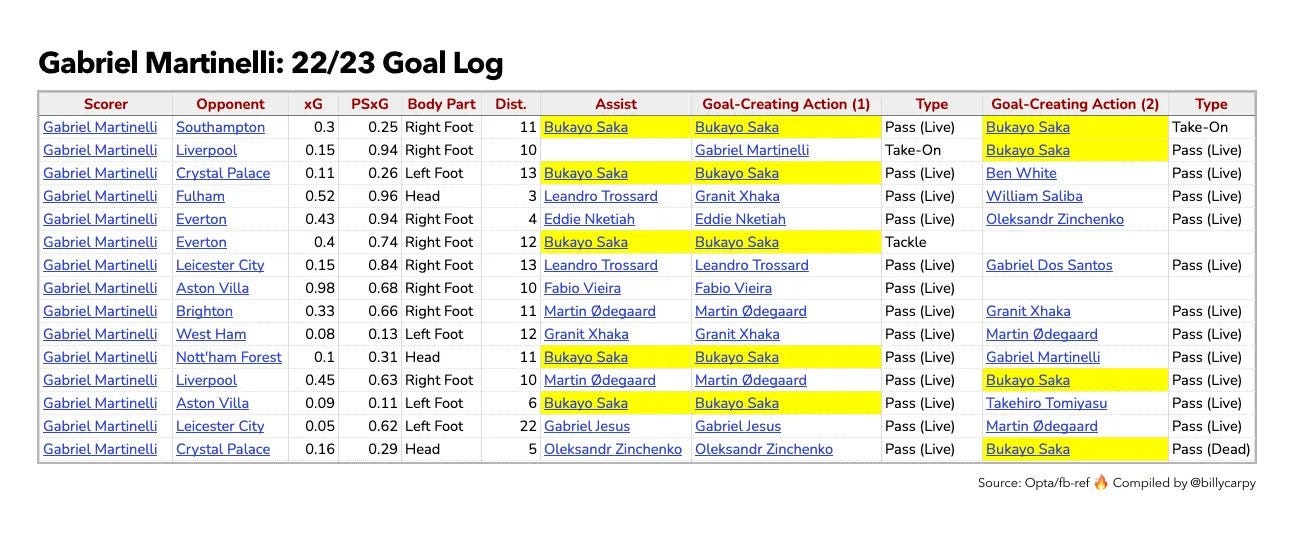

Last year, Arsenal led the league in how many goals they scored over their expected total (at +11.9, even with Manchester City), bouyed by Martinelli (+5.7), Ødegaard (+5.0), and Saka (-2.9). This year, they are at -1.9, and there are no notable overperformers.

This table shows how important that can be. Arsenal have yet to lose a game in which they’ve equalled or beaten their xG total.

There are two things to keep in mind while discussing this.

First, I defer to somebody a lot smarter than me: David Sumpter, Professor of Applied Maths and co-founder of Twelve Football. Take it away, David.

When scouting players we want measurements to be repeatable over seasons: that a player can do what they did previous season in the coming season. Finishing does not have that property, even over a season. Each dot below compares the finishing of a player between two seasons.

He continued:

Many other metrics do have repeatability … Knowing a player's finishing stats for a year can be useful. But signing a player because they "over-performed their expected goals" is very risky. This is also, of course, why xG is so important in scouting how well players get into good shooting positions. It is highly repeatable.

Finishing is fickle, in other words.

But it is also … not. The best teams fairly reliably overperform their xG. Here are the xG differentials for all the title winners over the last six years.

22/23: +11.9

21/22: +7.6

20/21: +15.8

19/20: +13.0

18/19: +6.7

17/18: +24.3

Do I think Arsenal are due for a bounce back up in luck? I do. I also think that Ødegaard’s new role has created some new angles for all the attackers, and they’re simply building fluency with it all. But do I worry that the set pieces and penalties may be due for some regression, as well, and the xG totals may rebound, but not up to title levels? I do, too.

🥅 The other goal

The other side is just as frustrating from an xG perspective.

Thanks to some weird moments (Newcastle over the byline, West Ham over the byline, Mudryk’s biffed cross, etc) and a bad performance by Raya against Luton, the non-penalty xG difference of Arsenal opponents is +4.2. They’ve scored around 5 goals more than they would expect given the quality of their shots, and 40% of their shots on target go in.

Though I expected an adjustment period for Raya, and I’m still frustrated in the occasional team mistakes (I had forgotten about Jorginho’s against Tottenham until this, thanks a lot) and last-line defending, I often wonder if a goal-keeper’s goal prevention is a lot more team-based and “associative” than commonly thought.

While lining up, a lot of thoughts grace a keeper’s head. Where are my centre-back’s lining up to block this shot? Will they jump on this corner or leave me to it? Where is my line of sight?

We often hear how other positions vibe together, but it’s true there too. The good ones block in tandem (one far post, one near post, etc). Sometimes it doesn’t work out, sometimes it clicks immediately, sometimes it takes a little time.

He’s still conceding less than Ramsdale did last year, while claiming crosses three times at much. The passing numbers have dropped a little closer to Ramsdale of late, but he’s still adding about 90 yards more of progression per 90 over last year. It’s early days, and I think we’re only starting to see the potential of transitional/long balls from him.

I’m patient.

Now, let’s talk about the big one.

🦅 The wingers

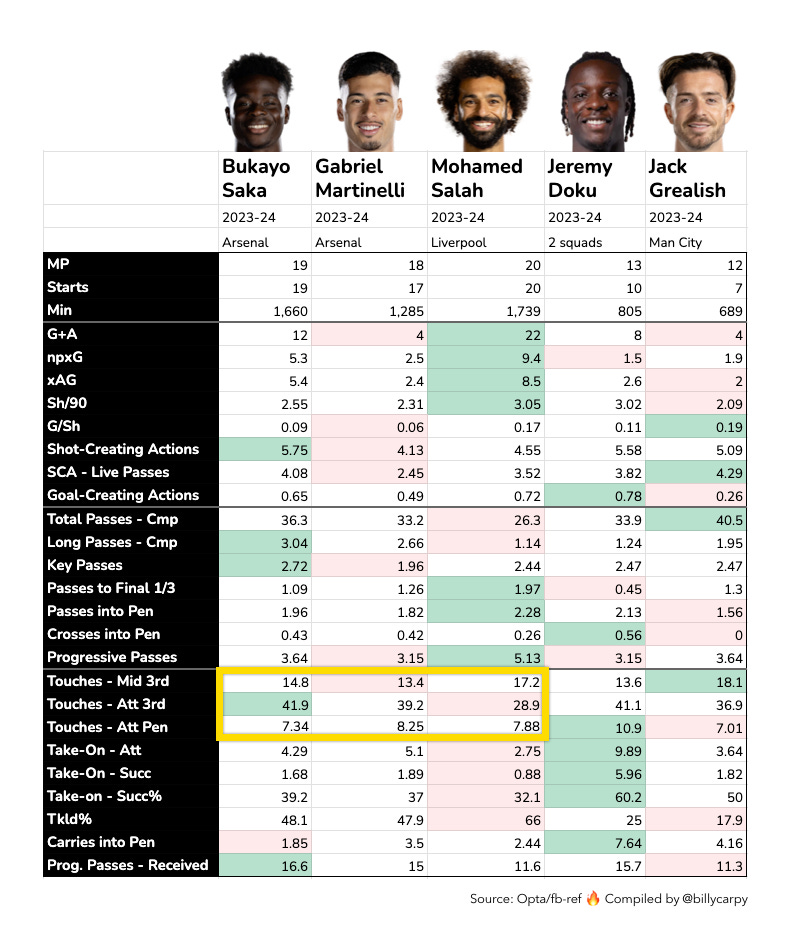

The Arsenal system, as it current stands, depends on strong production from its wingers. To help add context to how that’s going, I pulled data for Saka and Martinelli — and then pulled it for Salah, Doku, and Grealish too. The goal was to get a few different styles and see how they’re performing and being supported structurally.

There are so many interesting nuggets here.

For one, look at the touches. You may be surprised to find that Martinelli is getting 3.8 fewer touches in the middle third, and 10.3 more in the attacking third. This lets us know that the problem isn’t the quantity (or even raw placement) of the touches, but the quality and circumstance with which he may receive them.

Salah, surprisingly, has a higher degree of responsibility in progressive passes than either Arsenal winger — passing less, but doing so deeper, and progressing more.

Again, you’ll see that Saka/Martinelli receive ~5 more progressive passes per 90 each than Salah does. Again, this doesn’t judge quality, but shows something.

Saka’s underlying stats are, really, just fine. Here’s what I tweeted about him recently: “It's way too broad a brush to say Saka is in a poor run of form. He's been missing some shots (which, fair, is important in this sport) but his overall play is generally and casually as ridiculous as ever. Probably even moreso. We shouldn't let our eyes adjust.”

My thoughts on Saka are pretty simple. It’d be great to get him a healthier partner at right-back, but with Ødegaard dropping more, Saka can cheat into the right half-space and find a little bit more joy. From there, it’s on him to speed up his shot delivery and generate a few more.

It’s small margins, but I’d like to see him remove his prep touch more often. With so many people in the box, windows close so quickly, and so do angles. This is a tough clip for that, but hey, it’s the first one I could think of.

For Martinelli, the situation is more complicated. I would argue that his raw xG is as big of a problem as his actual goals/assists. It’s one thing if he were just missing shots, but he’s clearly not generating enough.

Even when factoring in his finishing quality, using Fotmob’s model, he has a lower expected goals on target (xGOT) than Matty Cash.

This requires further exploration.

🧐 What about Martinelli?

By now, you know the broad strokes: despite logging more touches, advanced touches, carries, and take-ons, Martinelli's goal production has waned — from 15 goals and 5 assists a year ago, to 2 goals and 2 assists in 17 appearances thus far.

There are a few bits of context. First, across competitions, he missed 6 total games with a hamstring injury. Second, his relationship with Gabriel Jesus has proven fruitful, but Jesus has missed 10 of his own. They’re a natural pair, with ample Gabi² rotations up front, plus moments like this.

That clip was from the Champions League, though, which leads us to a third factor (which may loom largest, in my eyes). In the league, Arsenal are now facing the lowest opposition defensive actions of any top-5 team in Europe.

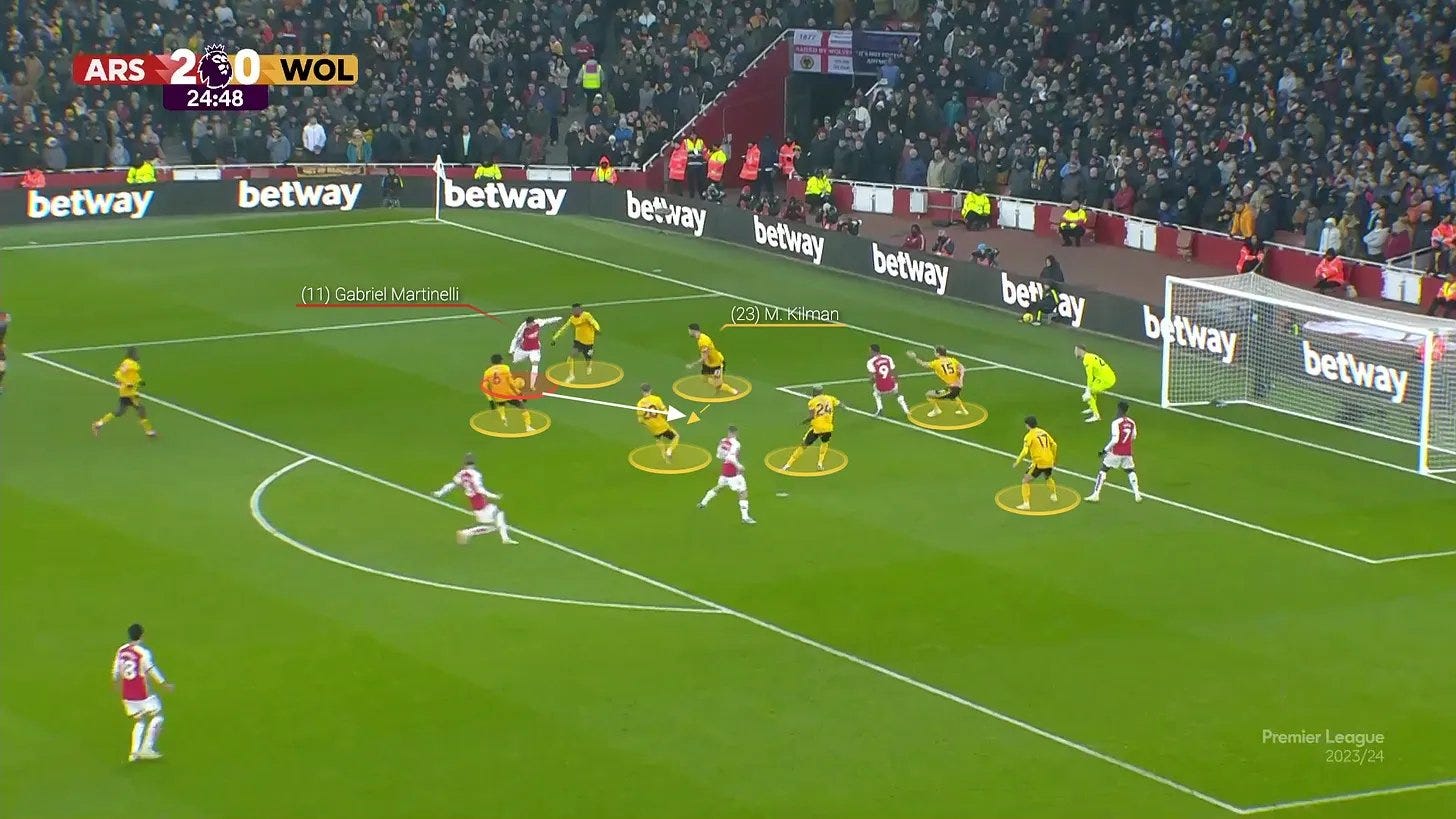

Martinelli thrives in chaos, looseness, and opportunism. Stacked boxes are a different beast to navigate. Lanes close immediately, as they did here when Kilman stepped in to block.

He’s adjusting — learning when to rip right away and when to take another touch. It’s a fairly big adjustment, and honestly, I think everything else about the situation is secondary to this.

The doubles have been slower to arrive in the Champions League, which has enabled this — which is still Martinelli’s best way of beating his man 1v1. He’s refining his unpredictability in direct take-ons, but there’s no refining necessary here.

Speaking after the game, Martinelli had this to say.

“Arteta asked me and Bukayo to be more direct and believe more in ourselves ... I want the ball as quickly as possible to have the advantage and take the full-back on 1v1.”

That’s why I’m hesitant to chalk this up to a simple “poor run of form.” In the end, I feel fairly confident that we could drop him back in the Champions League again tomorrow, have teams defend him like that, and he’d ball out. The issue is perhaps more specific: a difficulty adjusting to the new, crowded reality of Premier League opposition.

Meanwhile, he’s also shouldering additional responsibilities. Anecdotally, he seems to be generating more corners in a team with a set piece advantage—sprinting to the byline and kicking it off a leg. That doesn’t show up in the scoresheet, but may be a coaching focus.

That shows up in Arsenal corners this year, via fb-ref:

158 taken (25 more than anybody in the league)

51 conceded (22 fewer than anybody in the league)

Further, perhaps an under-the-radar change is the uptick in his own crosses — from 3.65/90 last year to 6.07/90 this year. Though his whips are fairly nice, these dynamics aren’t ideal. Ødegaard and Saka don’t make the most natural back-post targets, and Jesus isn’t always home. This cross was perfect, and literally no one went for it.

I’m not so certain that those numbers should continue if something doesn’t change tactically, or if different players can’t arrive there.

(Side note: do you know who is a top-3 threat in the world on such L-to-R crosses?)

Which brings us to the dynamics on the left side. The largest “void” is in the left-8, where the propa passing midfielder has moved on to Leverkusen, and a duelly, gangly, strikery, increasingly-understood heading giant has taken his place.

They have different styles, but make no mistake, Xhaka is the vastly superior passer. Passes like this (which set up a goal at Anfield) are fresh in the minds of all ye Arsenal faithful, and have felt sorely missed in certain games.

Havertz has been conservative with the pass, sometimes frustratingly so, though this has shown some scattershot signs of evolution.

For Martinelli’s sake, the big “delta” is whether Kai plays balls like this “out.” The blue line shows where he’s most often put it, “out,” with a priority on retention. The white line shows him playing Martinelli “in,” with a priority on trading risk for threat. This ball went in, and the end result was a goal. He’s capable of this in the future, but it certainly hasn’t been there enough so far.

But we must keep this all in proportion. What if I told you that in this one, magical moment against Man City — Kai Havertz equaled the Xhaka-to-Martinelli assist total from all of last season?

It’s true that Xhaka set up players all over the pitch, and assists only tell us so much. But as I watched all of Martinelli’s big moments from last year back in total, I thought: “Hm. A little less Xhaka than I remembered.”

One player did keep reappearing as a connection, though.

To double-check my eyes, I pulled Martinelli’s goal log — and there he was, strewn throughout, with 9 GCA for Martinelli’s 15 goals, plus three more GCA going the other direction.

Bukayo Saka. Of-fucking-course.

Perhaps it’s unsurprising that one of the best playmaking wingers in the world delivered such service. But with the two on opposite ends of the pitch, it may be underappreciated how direct their relationship can be. They are wingmen.

The simplest example is this. There’s a cutback cross, Jesus brings gravity into the net, and Martinelli finds the soft spot behind.

Goal. He can be lethal on those.

Here’s another one. Left foot. Nice and satisfying.

But this one may be most illuminating. Watch how this is essentially a 2-man game with Tomiyasu as a +1. Instead of being too demonstrative (or u-shaped) shuffling it around, it’s direct, and the block is unable to go back and forth with enough speed. Too hard to track.

...and that's an essential weakness in these blocks. They can pile in. But if you're too quick with the change of directions, there's no way they can double both wide areas and block every lane. But if you're too slow and require too many intermediaries, you miss your chance.

There are a few reasons why this is less prevalent this year. Constant doubles make it hard. Martinelli has often stuck a little wider, a little further out on crosses. The changes-of-direction have made control a priority, and to my eye, require more touches and seem much slower. We saw that against Fulham.

In this video, illustrating a slightly different method of attack, you'll see how much the speed of the switch/decision increases their defensive vulnerability.

But Martinelli has been getting more wide diamonds of late. He’s been rotating more centrally. Dynamics are generally improved, but they can improve further. Yeah, he needs to be played in behind and centrally a bit more.

He’s also missing shots. He’s adjusting to the blocks. There are plenty of little 1v1 things I’d like to see him improve on. I would like to see him switch up top in the block some more.

Later in the contest against us at Anfield, Salah rotated to the CF spot to pounce on transitions. That wasn’t the right thing to do in that game state. But when he played against West Ham, you’ll see what fruits that can bring. I’d love to see Martinelli up here more often, cheating forward.

But as we’ve covered, title winners require xG overperformers, and Martinelli is one of our best hopes. If I were to look for one specific improvement, it's much more of this — trailing runs in the soft spot. Cleaning up in the reverse Ø-Zone. Havertz helps (not hinders) this effort.

🔥 Final thoughts

It wouldn’t be difficult for the entire message of this huge post to be “tranquilo.” I’ll start with that stuff.

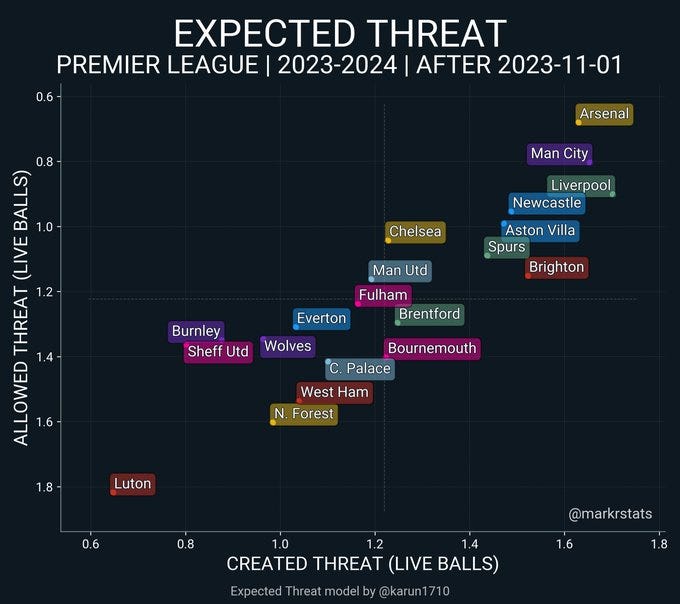

For one, here is a look at expected threat for the year, per @markrstats:

And here is a look at that since November. Again, I think this was before Fulham, but the point remains.

Arsenal have had a great run in the Champions League thus far, and indeed look well-suited for that kind of play. Meanwhile, the team has been generally been under-producing all of their underlying numbers, while their opponents have all turned into Puskas.

Furthermore, there are reasons to believe that things are on the upswing, but they are just not showing up in the table yet. Since Ødegaard moved roles, Arsenal have had a higher npXG (1.96) than they did in the first half of last season. They’re generating enough chances, threat, and dangerous passes; they’re just not slotting them home. That should improve (though football often does not care about the word “should”).

These stretches happen. Last year, around this time, there was a 7-game span in which Arsenal underperformed their xG in every game, going -4.6 total.

And we also shouldn’t act like all of these problems are self-manufactured. The other teams have their say. Production dipped in the back half of last year, too, as opponent game models improved, and teams increasingly packed the box. In the Premier League, yesterday’s price is never today’s price. Stasis is a risk in itself.

But there are issues.

And so, in the final summation, I’ll leave you with some bullets on what I think about it all.

Arsenal are generating too few open play goals. While they’ve been under-performing the metrics, and opponents have been over-performing their own, Arsenal have also racked up set play goals and penalties at high rates. There is some reason to worry that any improvement may be cancelled out elsewhere.

Ødegaard’s role update has been transformational, and led to so many of the desired improvements. If you pay enough attention, Saka has been more inside, Martinelli has been freer (and seen more diamonds and support coming his way), and a lot more shots are being generated.

It is not without drawbacks, however. For one, having an over-fluid build-up has risks with defensive solidity, as players are often transitioning between zones. With the full-back more likely to be found out wide, the “rest” defending carries a little more risk of being played through. I personally think it’s a worthy risk to take.

But the big drawback is that this shift increases the intensity and burden of two players, at a time when planning and circumstance have left the midfield thin: Ødegaard and Rice. This is in addition to the understandable exhaustion felt by the wingers and the right-back (White).

For Ødegaard, I’d still keep this up until the summer, but he needs support. Depending on game-state, he can be more regularly subbed for ESR or Jorginho. The former should get ample minutes to perform.

Rice will likely have to play almost every minute for this all to work out. I believe he should receive his (marginal) breathers at the #8 position. He should be able to do this more often with depth returning to the #6, and the possibility of the “diamond” formation returning (which I’d welcome). We’ll see if/how Partey can contribute, but I’m not sure how wise it is to count upon that.

White and Saliba are currently “single points of failure.” I wouldn’t let January pass without a reinforcement in this general area, even if it’s short term. My personal preference would be for a practical loan (Chalobah comes to mind) or a truly flexible, explosive wing-back who is additive to what is currently on the squad list (say, Kadıoğlu, who is sneaky depth elsewhere). If something like an Osimhen/Zubimendi summer looms, I’d want to do whatever we can to preserve that, but as I’ve written before in my PWR rankings, I’m also on board with a Big Boy midfield signing that provides general, flexible depth in this area of the pitch: Fofana, Onana, Wieffer — but I’d probably only do so if we knew our top summer targets were unavailable. I’ve had a Palhinha post slow-cooking for a while now.

Hopefully people are increasingly seeing the value of a player like Osimhen.

The big questions are up front.

xG and luck should naturally improve, says the hopeful idiot.

Saka must take advantage of the semi-vacated half-space. He needs to learn from Salah in respect: the sheer immediacy of some of his actions. More first-touch shots and snap crosses, please.

With Martinelli, I’d look to have him get fewer touches, drive in a few less crosses, and get a lot more shots off. Ødegaard’s freedom helps here too; he can hit Martinelli himself. In the final third, I like him freelancing around, becoming ungovernable, and especially attacking the soft spot in the middle of the box on a cutback cross.

Getting the wingers the ball a little bit quicker, and having them act a little more decisively, is an obvious key to things. A less-obvious thing is increasing the amount of times they’re interplaying with one another directly.

I’d like to see Jesus rotate down on the left more often in defensive coverage, so Martinelli can be at the top of the block to get hit on the counter immediately. That falls into the category of “centre-back nightmare fuel,” and Raya and Co should fire those off in big quantities. Meanwhile, Havertz can improve his deliveries, especially in transition, and I think he can swing out wide a bit more. But I think that problem may be over-stated.

I think Tomiyasu at left-back is a nice way of getting Martinelli free in transition. Hopefully he can cheat up a little bit more. If the Tomiyasu inclusion over Zinchenko hampers build-up, as it probably will, just have Havertz and Jesus switch, blast it long to Havertz, and have Martinelli run off of him. The Tomiyasu/Martinelli half-space interplay actually looked really nice in the Champions League.

With Ødegaard dropping deeper, somebody must fill the void as “connective tissue” between the build-up and the attack. I like Jesus in that role, dropping a little (but not too deep) and turning quickly. Again, the entire Arsenal complex has to get a little bit more comfortable with losing the ball to generate threat, and Jesus is a player who has a good relationship with risk.

There are interlocking on-pitch relationships that must be accounted for. Havertz and Nketiah have combined for two goals of late, but ultimately, I think their profiles aren’t all that complementary. If Nketiah starts, or Havertz starts up top, I’d personally like to see Vieira in the left-8.

As the season progresses, the entire team — but particularly Rice — should dribble through the middle more. Arsenal’s best performances have a strong relationship to “carries into the penalty area.” They unsettle blocks and move people around.

Rice is the last of my worries, sorry. He can push up a little bit more centrally in build-up, and unsettle with dribbles from there. He can have a slightly higher risk profile. But every pass in his bag, and I find his improvement to be such a given that I’m almost bored with the discussion.

As you could perhaps tell, I was on the road for the holidays, with spotty access to internet — but was keeping copious notes throughout. I hope you enjoyed them all.

Be good, everybody.

❤️

Nice to see you experimenting with short-form <3

Thank you so much for this! I needed this a lot after being exposed to all the engagement-driven twitter negativity