What's the difference?

An investigation into the different styles, speeds, and stats of Slot's Liverpool and Arteta's Arsenal

It is said that comparison is the thief of joy. After the last two seasons, one would assume that a comparison to the current iteration of Manchester City would bring us a larger measure of happiness. Instead, Liverpool have played the thief.

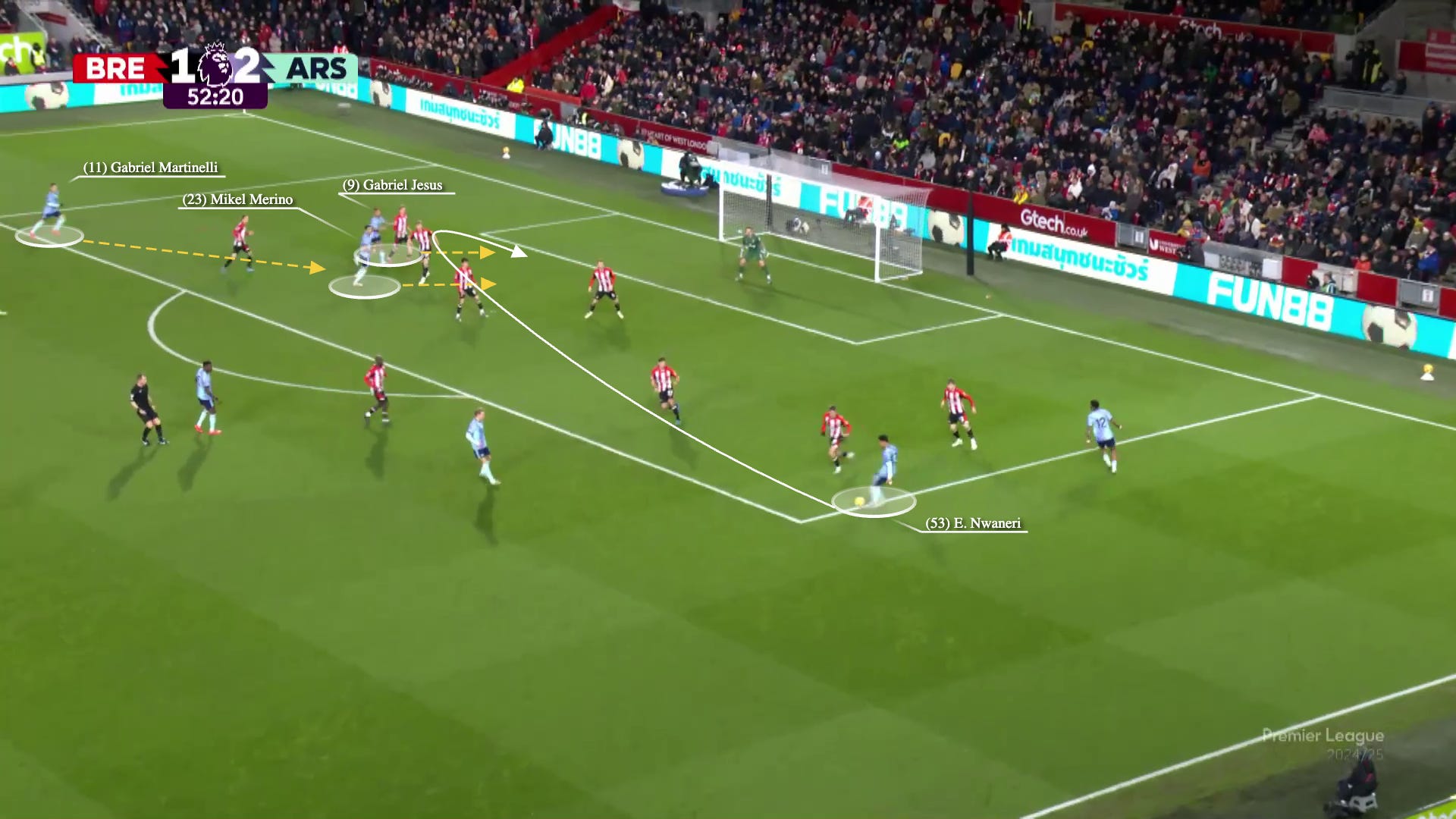

A frigid Saturday in Brighton left us cold. Ethan Nwaneri livened us up with one of the best-feeling goals of the season; then he got injured, of course, and a tired and sick Arsenal squad increasingly looked sick and tired. Without White, Timber, or Tomiyasu starting at right-back, the team has plodded to similar performances against Newcastle (0-1), Fulham (1-1), Everton (0-0), and Brighton (1-1).

Liverpool then drew Manchester United at Anfield on Sunday, which may oddly make you feel worse about Saturday, but will also leave the door open, if barely.

Meanwhile, Chelsea have dropped ten of their last twelve points, Nottingham Forest are defiantly lurking around, and much could happen in the months ahead. However many horses you think are still in this race (I still basically think two — sorry Forest), one has a formidable lead.

What separates those two, uh, horses? Mostly the obvious. Mohamed Salah is on pace for the greatest individual season in Premier League history. He’s got fucking 31 fucking G+A in 19 fucking games. Fucking. He seems to be taking a decade-or-so of nonsense Ballon d'Or voting out on us, for whatever reason, and I don’t appreciate it.

He is not doing this alone, however: team conditions have to be primed for that kind of production. He’s joined by a manager offering pure and subtle tactical soundness, a compilation of a few all-time greats, brilliantly reimagined players like Ryan Gravenberch, and bursty try-hards. They haven’t looked overly lucky from an xG perspective, and indeed, the underlying numbers show a team that “deserves” their place atop the table at this juncture, whatever that means. They’ve also been fortunate with injuries, schedule strength, and especially the misfortune of their competitors. They certainly didn’t look impervious against Manchester United. There are little cracks for those interested in finding such things.

Things may get tougher from here. As Orbinho tells us:

Of Arsenal's remaining [eight] Premier League away games, six of their opponents are currently in the bottom seven of the table. Trips to Forest & Anfield are the exceptions. In contrast, Liverpool have to visit 7 of the current top 10 in their remaining 10 away games.

Arsenal, on the other hand, have had our misadventures. The difficulty has been high, the lineup sheets have rarely resembled our “Best XI,” whoever that is, and after three reds, we’ve played 8% of our total minutes while down to 10 men (Liverpool are at ~4%). The charitable way to cover That One Topic is “Arsenal have been on the wrong end of several important and marginal calls.” The less-charitable way might get me banned from Substack. This and the injuries pile up, and the baggage gets weighty. Liverpool ultimately drew to a Partey-White-Kiwior-MLS backline, he mentions ruefully to all who will listen, and a period without one linchpin (Ødegaard) is now followed by a longer period without another (Saka). Scousers remember life without Van Dijk.

Look, Harry Maguire nearly beat Liverpool at Anfield on a counter, and Carlos Baleba and Jorginho somehow not only share a profession, but a position. Football is weird, is the point. Could fortunes turn enough for a title? Especially after Brighton, and especially without Saka, the dopey optimist on your left shoulder and the hardened realist on your right will disagree. The realist has more evidence for his case.

It’s a narrow path. It requires more shots and goals by Arsenal.

With that, I thought it’d be interesting to see what currently separates the two teams statistically. I wanted to examine the respective play-styles of the two contenders, and see if one is charting a more sustainable passage, and whether some of the broad-stroke narratives withstand scrutiny. Some of this will just confirm the glaringly obvious, but some of it will hopefully enhance our understanding.

While Arsenal have some superiorities over Liverpool, it’s worth investigating what, exactly, has been the difference so far, beyond what we may already know.

As it turns out, there were a few things to learn.

👉 The basics

I am indebted to fbref.com (as always), and @DataAnalyticEPL for their incredible data viz work, which is leaned upon below. Please follow and support them however you can. I’ll also mention that while most graphics and stats were updated since the weekend, a few are a couple of days old.

Let’s start with a quick overview.

Here, we see that:

As of this writing, Liverpool are up six points and have a game in hand.

In so many words, this is basically because they manage 0.57 more goals per match than Arsenal do. That’s really all there is to it.

Arsenal have now resumed their place as the strongest defensive team in the division, and perhaps the world. I’d personally expect that gap to grow a bit.

As the difference in attack is the difference in the table, that deserves our most focus. It’s worth remembering that there are different ways to skin a cat. (What a weird expression that is; it must have started when cat-skinning was more en vogue.) Just because something is right for Liverpool does not mean it’d be right for Arsenal.

Nevertheless.

👉 Building out from the GK

One of the most noticeable contrasts in play lies in how each team approaches deep build-up, particularly through their goalkeepers. For Arsenal, this role has been handled by David Raya, while Liverpool has split the responsibility between Alisson and stand-in Caoimhín Kelleher.

Arsenal do all kinds of swirling rotations and situation-specific changes. There’s Raya as a CCB, the possibility of inversion from both sides, Ødegaard dropping into the pivot, and the LCM going high, low, or wide. Raya is constantly counting, and as soon as there’s man-to-man on the backline, he’ll draw them in and go long.

While Liverpool can deploy subtle tweaks based on the amount of pressers flung forward, they are generally more stable in their approach. It’s usually an expected 4-2 shape in the back, not too dissimilar from those De Zerbi teams, with a double-six midfield and another midfielder floating on top. These back-seven players put it in play fairly quickly and calmly pass it around until a free man is found.

To be clear, Arsenal do this too…

…but are more inclined to keep trying out different configurations.

As you will see below, Arsenal are also much more likely to launch the ball from GK than Liverpool.

This is partially due to personnel: in Havertz, Jesus, and Merino, Arsenal generally have better targets. But it’s also clearly strategic: Liverpool’s keepers have the shortest passes in the league, while Raya launches it 5+ more times per match.

This leads to the rise in aerial work.

In all, Arsenal contest 6.87 more aerial duels than Liverpool. The “win rate” and “completion percentage” on these stats are not altogether indicative, as the goal is to win the situation, not necessarily the stat. Nevertheless, Liverpool have the highest win percentage in the league.

While Arsenal are happy to engage in aerial duels, one wonders if there is a slight over-reliance here. It’s set up for success, but a bouncing ball situation is never fully controllable and is likely to add a bit of variance to the proceedings. Launches also generally take longer to set up.

This brings us to our next stat, which certainly looks negative on its face: passing progression.

👉 Ball progression

Here, you’ll see a big gap in progressive distance.

This is a little more confusing than outright bad. Of note:

Arsenal are 15th in progressive distance via pass

Liverpool are #1

Liverpool also have more progressive distance via carry

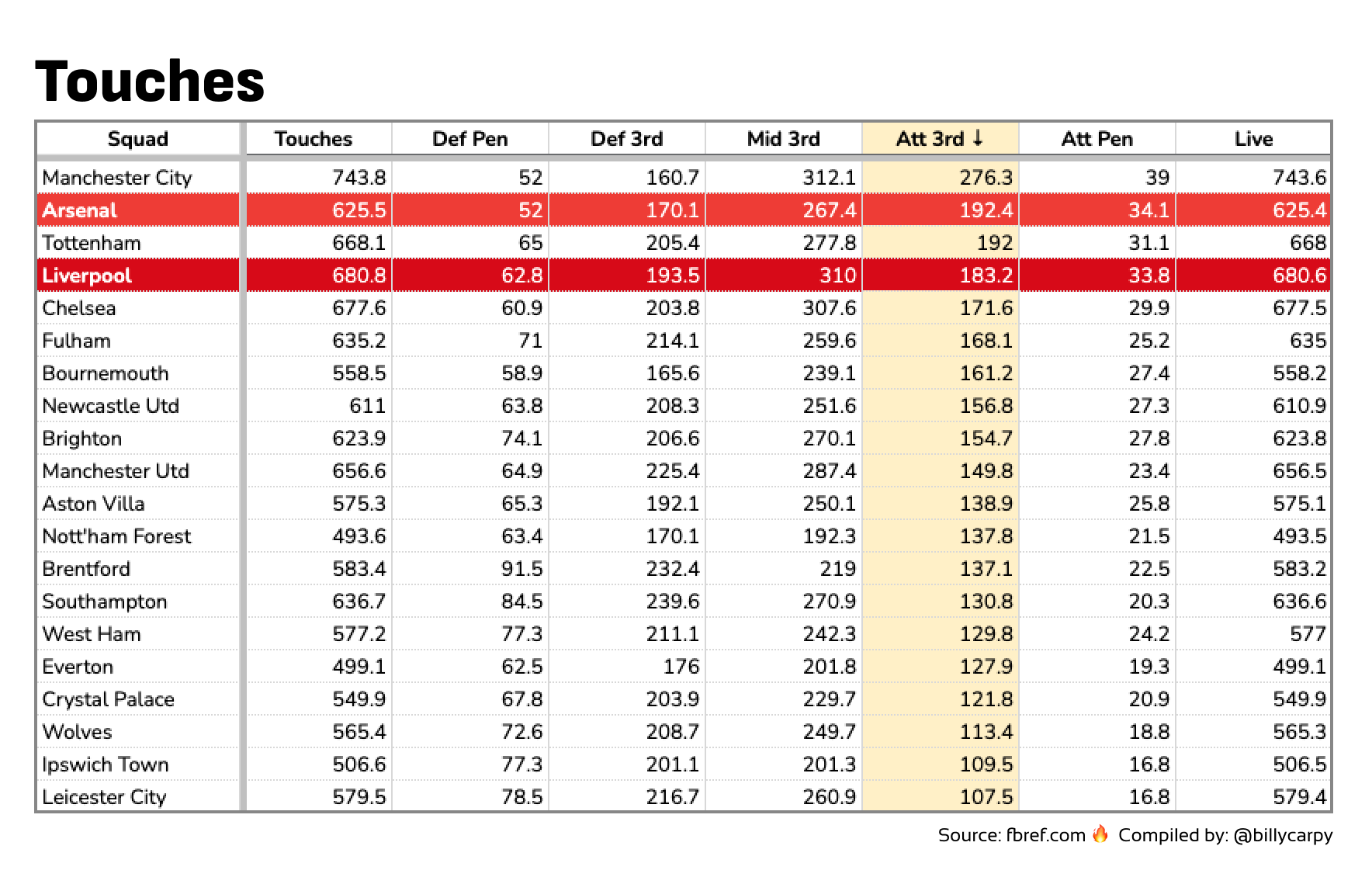

…yet Arsenal still have more touches in the advanced third than Liverpool

My pal Jake just wrote a long and highly interesting piece on progressive passing for SCOUTED. The definition is a little different than you may think:

Completed passes that move the ball towards the opponent's goal at least 10 yards from its furthest point in the last six passes, or completed passes into the penalty area.

That means that a) progressive passes must be completed to be counted here, b) progressive passes include any entry into the box, which are often short distances, especially for Arsenal and c) they have to be at least ten yards. (In a curious quirk that I just found, I believe ‘total progressive passes’ can’t include completions within 40% of your own goal, but ‘progressive distance’ can. Have I lost you yet?).

What’s interesting is what we just mentioned. Despite all of this, and despite worse game-states, and despite lower possession and touches, Arsenal still have more touches in the attacking third than Liverpool.

So… it’s basically this meme.

What gives?

Perhaps a large part of it is about what we touched on earlier: David Raya has a 33.9% completion rate on launched passes, which is fairly normal, but he hits these at a higher frequency than other top sides (besides Forest, who should now be included in such discussions). This fast-tracks the ball to the other side, but again, only completions count as “progressive distance.”

Along with throw-in delays, corner delays, and fouls, Arsenal generally keep the ball on the actual pitch less than a Liverpool, so there’s less time for standard passing.

It’s more than that, though.

While it’s tempting to say “Arsenal just win the ball more up the pitch,” that’s not blatantly true, as we’ll cover.

A lot of this is just down to the respective play-styles.

👉 Intent, “good height,” and “same side”

On the Liverpool side, this evolution was telegraphed by Curtis Jones, who was positively giddy with the changes that Arne Slot was implementing in the preseason.

“Mo Salah will always get us goals but we need to be comfortable on the ball and be calm in our build-up as a team,” said Jones. “We're not in a rush to attack. We need to break teams down and when we give the ball away we can press. In the past it was a rush to get the ball back, a bit too direct, up and down, up and down. Now we want to have all the ball and completely kill a team.”

Slot is big on crediting the deep work with the advantages in front. After the 6-3 shellacking of Tottenham, his eyes drifted backward.

“If you watch the goals back, it mostly started off with centre-backs or full-backs.” “Every lead-up to a goal was, I think, multiple passes. So, it’s not only (about) the ones that score, it’s also the ones that help to create.”

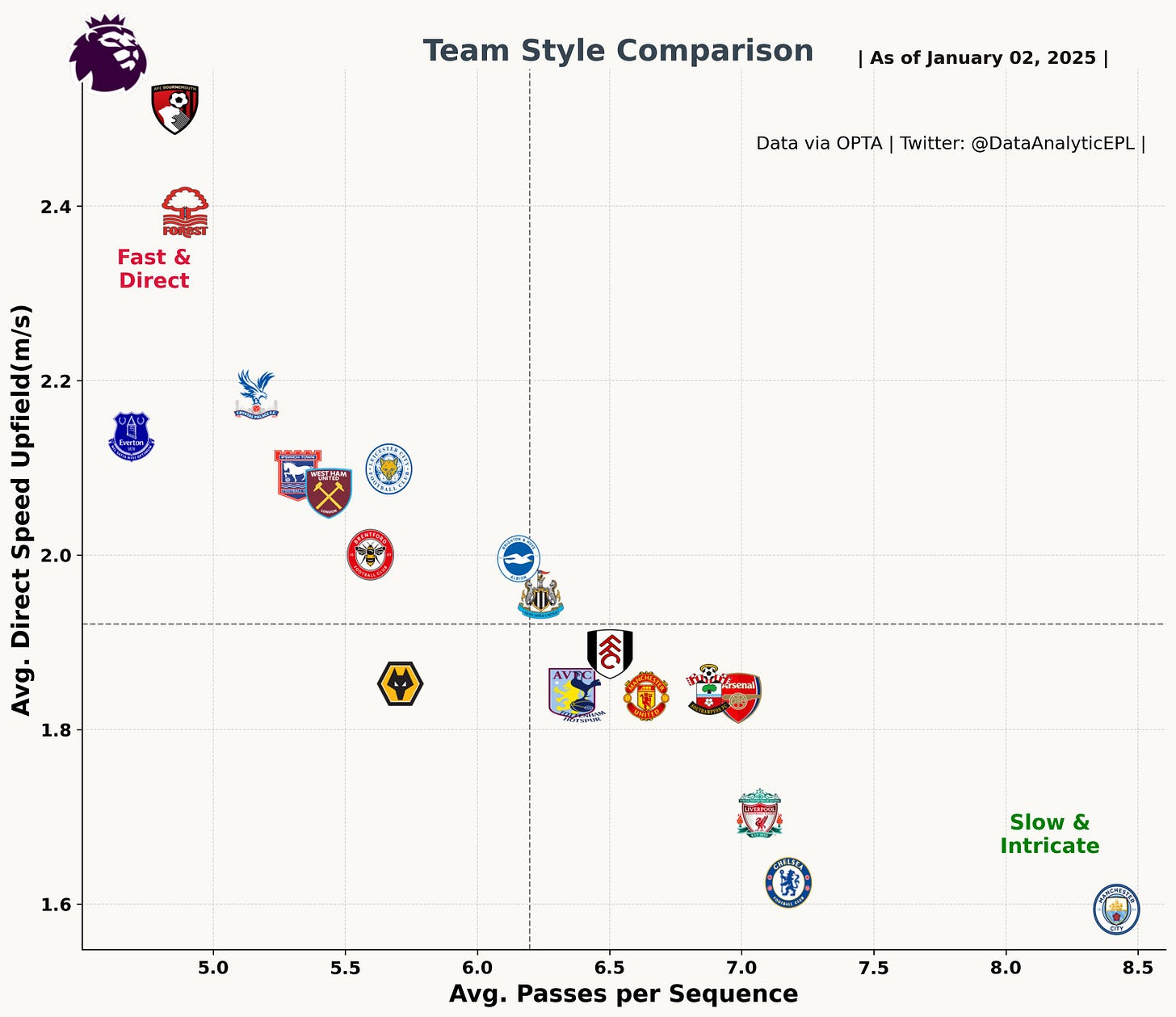

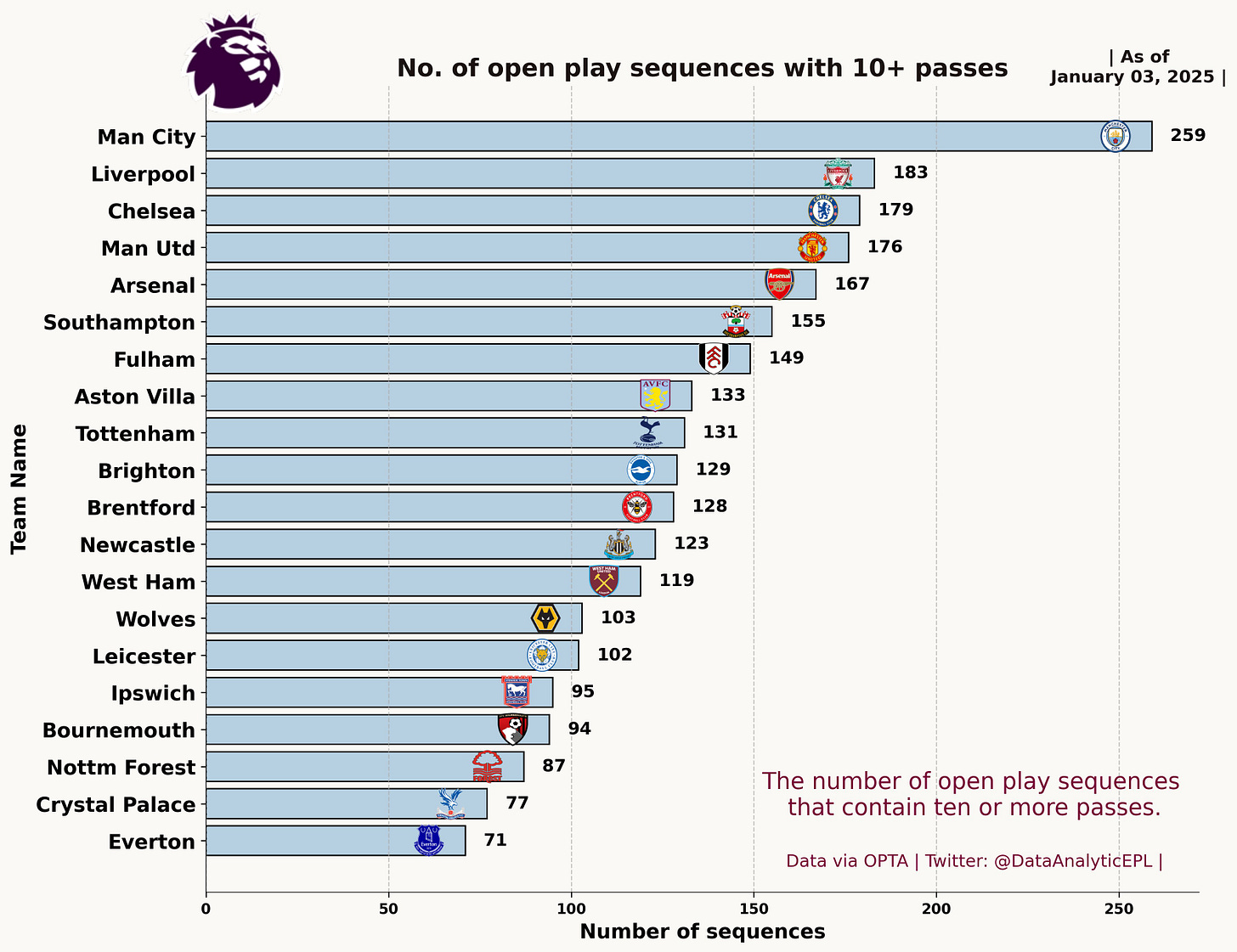

This leads us to one of the primary differences, which was hinted at by the goalkeeper distribution. Liverpool offer more passes per sequence, and a slower speed upfield.

This feels like a narrative violation. Liverpool are slower?!?

Yes and no. This difference is shown by where the respective teams like to keep the ball during the game.

Despite Arsenal having more advanced touches, here are the touches in the defensive in middle thirds:

Arsenal: 437.5 touches per 90

Liverpool: 503.5 touches per 90

That’s a pretty big delta. It results in longer spells of standard progression.

Whereas Raya handles most of Arsenal’s long distribution himself, Liverpool wind up going long more often in total. This is primarily through Trent Alexander-Arnold (15.4/90), but the likes of Robertson and Van Dijk join in as well. If they spot a dynamic run in-behind after a few passes in back, they try to hit it.

This is one of the clearest distillations of the difference. TLDR:

Raya is the long-ball threat for Arsenal. Because he is a keeper, he generally gets the ball up near the edge of the final third in an aerial situation.

Alexander-Arnold is the long-ball threat for Liverpool. Arsenal don’t really have a corresponding player in our back-four. He doesn’t just get the ball to the edge of the box. He gets the ball into the box. These are generally targeting lower-percentage but dangerous in-behind runners.

Arsenal’s more advanced possession can be attributed, at least partially, to two aspects of the Arsenal game-plan, which can be summed up with two phrases: “good height” and “same side.”

On the former, Declan Rice expanded upon this in a great Athletic piece:

“The manager calls it playing in a ‘good height’,” Rice said when talking about more advanced pockets he would occupy when playing as a No 6 … Arteta is obsessed with keeping the ball as far away from Arsenal’s goal as possible, for as long as possible.

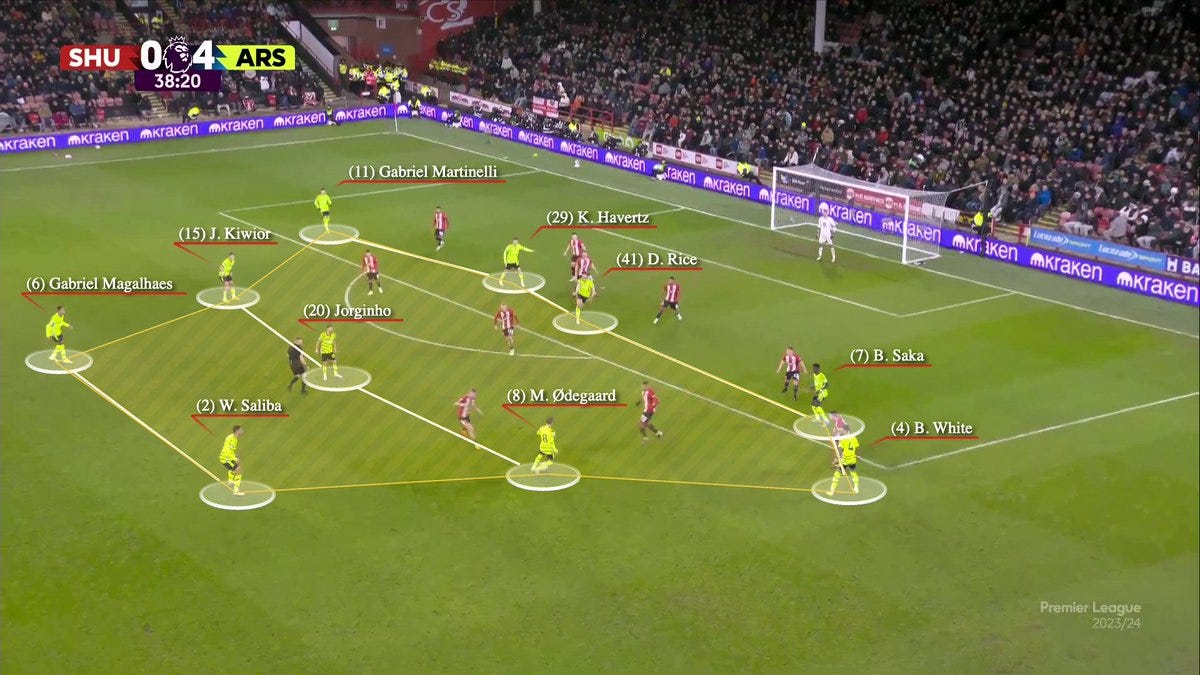

The platonic ideal looks something like this: a possessional cage, uncompromising and determined, blunting any possible attack by the opponent.

Despite the obvious advantages — counterpressing, sustained pressure, the difficulty of the opponent getting out of this to move forward and counter — the article also outlines one of the drawbacks:

“The only issue is there is only so much space to work with.”

This leads to close distances, crowded boxes, and sequences of endless “pinning.”

This is true from a pure distance perspective. From Markstats.club:

Arsenal face deeper opponent defensive actions than Liverpool (39.73 metres from goal to 41.49)

Arsenal have higher defensive actions than Liverpool (50.22 metres from goal to 47.65)

There are chicken-and-egg factors here, and that distance isn’t too stark. But it also feels true when watching the respective games.

Aside from “good height,” Declan Rice also talked about playing “same side.”

“We’re really big on playing ‘same side’,” he said. This was in relation to Arsenal probing for an opening on one side of the pitch rather than recycling the ball to the other flank.

This is shown in those endless little bits of combination play, usually concentrated on the right in recent years.

Or this.

The numbers all back this up.

Arsenal have been an outlier with how much they funnel play to the flanks, and how little the ball goes through the middle. Liverpool are more determined to find advanced midfielders in central pockets.

For Arsenal, this is strategic rather than incidental. The idea is that it:

a) dulls the opponent’s countering threat, pulling those wingers deep to the corner flag

b) avoids risk of central ball losses, and

c) has provided plenty of the ball to Bukayo Saka.

In the current moment, this will get held up as a subpar model for playing, and I believe it needs some tweaks. We can hold that in our minds while acknowledging it did deliver 86 goals and the best defensive performance in the world last year. But things change, and we know the trade-offs, too.

This has a few implications. First, Arsenal attempt and complete more passes into the final third than Liverpool, and possession is safer up there.

But we can also see how it comes out directionally. In overall passes, via Opta:

Arsenal pass direction: 28.79% forward, 15.37% backward, 27.94% left, 27.89% right

Liverpool pass direction: 31.45% forward, 16.57% backward, 24.90% left, 27% right

Basically: Arsenal are more likely to go out to the sides. Liverpool are more likely to go forward-and-back, and recycle deeper when things aren’t working.

While for Arsenal, this leads to some of the highest rates of “sustained attack” in the league.

This puts space at a premium and can make it more difficult for shots to find open lanes.

On that…

👉 Shots

Here is some shooting data:

There’s not a huge difference between the quality of the respective shot (0.14 xg per shot to 0.13).

The xG “over-or-underperformance” isn’t markedly different, either. In fact, Arsenal are performing marginally better in this measure. In others, Liverpool are a smidge higher.

It comes down to the simplest number: Liverpool shoot 2.7 more times per match than Arsenal.

…and despite that, among those shots:

25.6% of Liverpool shots are blocked

29.9% of Arsenal shots are blocked

They let it rip from a little longer, and still manage a higher percentage of shots on target.

It helps to have Mo Salah. But to raise your goal count, you generally must raise your shot count (and quality). Arsenal need to narrow that gap, and to do that, they need to hit it more freely, and generate less-crowded boxes. How? We’ll cover that later.

👉 On the ball

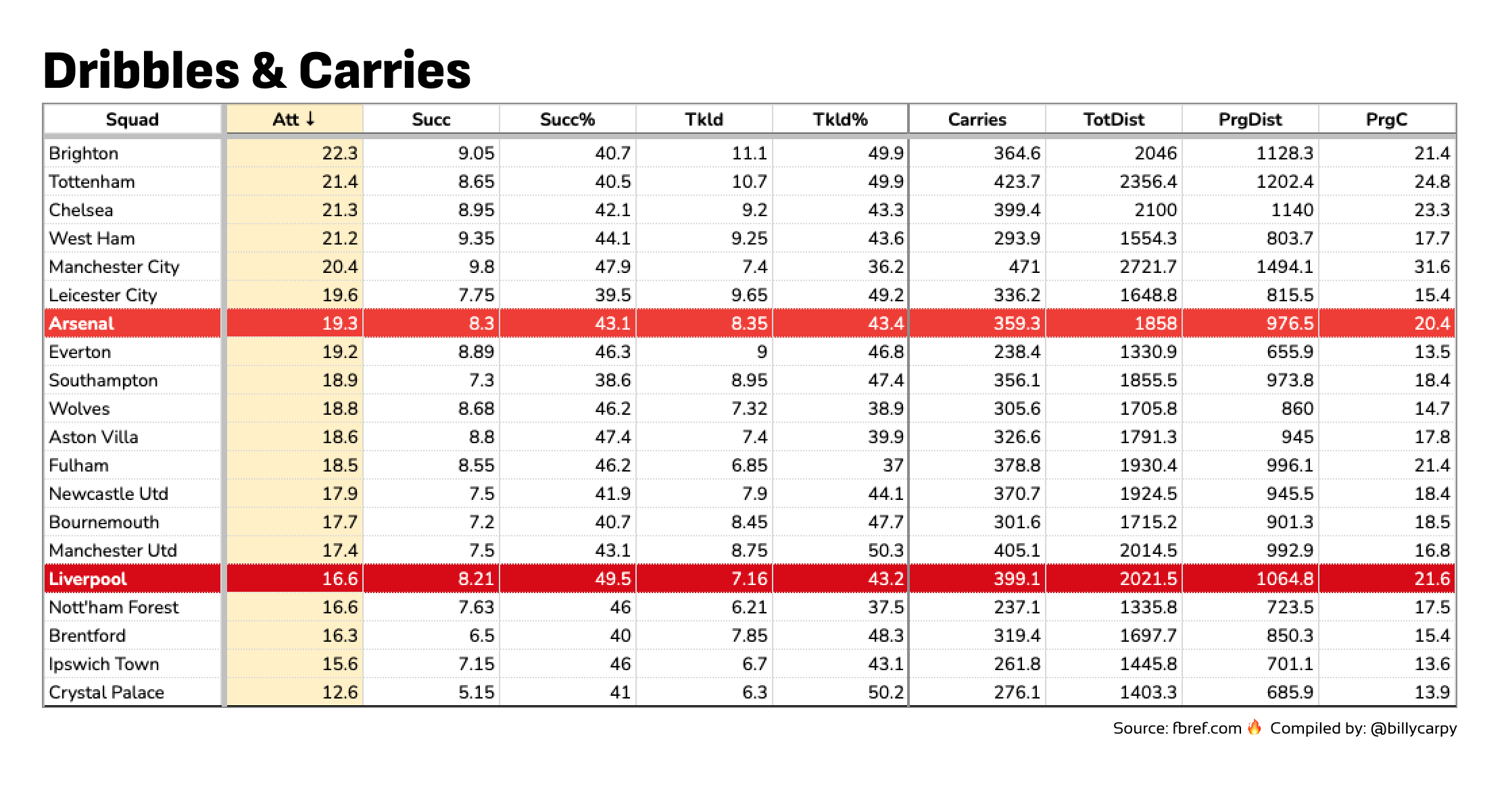

In another possible #NarrativeViolation, Arsenal are generally more voluminous as dribblers.

This all has been interesting to watch worldwide. There are multiple ways to be successful in attack. Powerful dribblers like Morgan Rogers are running riot on hapless midfields like Manchester City. Meanwhile, though, Inter have become the most tactically fascinating team in the world to me — and they’ve done it by forgoing take-ons.

This chart is pulled from this wonderful piece by Achraf Lamdarhri: Inter Simone Inzaghi — How To Score Without Dribbling.

You’ll see Liverpool in that top-left quadrant, with Arsenal further right.

There are some nuanced numbers from there:

The total carrying numbers tilt in the direction of Liverpool, largely through two methods: the defenders moving the ball forward to the first line of pressure, and through finding the free man in build-up.

Liverpool forwards are largely absolved of progressive responsibilities, except when Díaz drops to receive. While other teams may use players like Grealish, Mitoma, Saka, Martinelli, and Kulusevski to force backpedals and push the team up the pitch, Liverpool forwards are generally … forward. To make an extreme case for reference: Aaron Ramsdale progresses the ball more via carry than Mo Salah. Salah is currently 183rd in the league in progressive carrying distance; relatedly, he is first in touches in the box. He is so often high and central. Where will he hurt you the most?

There is a corollary to this. Though Arsenal dribble more than Liverpool, and Liverpool are generally lower on total dribbling lists, they lead the league in take-ons that end in a shot (2.26/90), and are second for carries into the penalty area (8.84/90).

Basically, they give it to their forwards in tricky, fast situations and ask them to beat their man.

Put simply: they are more measured with dribbling in deeper areas, and when the time is right, more aggressive in advanced areas.

👉 Defending

Outside of the more clean 4-2-3-1 build-up shape, Slot’s biggest change to the Klopp system has been toning down the riskiness and physical burden of the Liverpool press.

In truth, things got a little silly last year. I have so many memories of Alexis Mac Allister desperately trying to tackle somebody in acres of space. He wound up with the second-most missed tackles in the Premier League, with 66. Trent Alexander-Arnold was second with 60.

This time, things are generally more pragmatic. It has variations, but you can look at it as a simple 4-2-4 that generally blocks, and jumps if real conditions are met. That first line can be fairly aggressive but easy to play through. This is because the two midfielders aren’t always overly effusive (i.e. man-to-man) in their support. Except in certain situations, like the Man City game, they’re not concerned about showing maximum numbers high. They want numbers back.

Even Szoboszlai, the hyperactive sheepdog of last year, looks (a little) more measured.

This discretion has had tangible effects. Per PFF:

Liverpool rank 20th in total distance covered per 90 this season (compared to 9th in 2023/24) and 13th in high-speed runs per 90 (compared to 3rd in 2023/24).

For this piece, that may be the most important statistic of all.

Out-of-possession, the result is a little funnel in which the opponent threads play through the middle. Then, Liverpool aggressively pounce from there.

They definitely look a little vulnerable and imperfect to me. Alexander-Arnold and Robertson at full-back, behind a Mac Allister and Gravenberch double-pivot, just screams solid-not-great to me defensively. When stretched, you can make them pay. But it hasn’t really bitten them yet. Van Dijk could handle most attacks on his own, but Slot almost always gives him support. For lack of a better term, things seem a little basic.

Essentially, they save their legs from excessive running, and don’t intervene up high quite as much. After that, though, they dive in hard when the spaces get tighter. Compared to Arsenal, they are more likely to tackle in the middle and defensive thirds, and significantly more likely to challenge dribblers. Arsenal, of course, don’t have many dribblers to challenge.

More tackling does not mean better. You can see the list of teams to confirm. But this still helps us paint a picture about overall activity, and how they’re able to generate those snap-counters.

Here are players with more than 5 recoveries per 90:

Arsenal: Jorginho (7.25), Merino (5.68), Rice (5.31)

Liverpool: Bradley (6.30), Mac Allister (5.92), Gomez (5.86), Alexander-Arnold (5.42), Gravenberch (5.25), Szoboszlai (5.08)

This is where one can’t help but assume that Arsenal’s defensive injury list has had a direct impact, leading to lower engagement. We’ve had derbies of a Jorginho/Partey pivot. When fully fit, Arsenal just have bigger and stronger players in the middle.

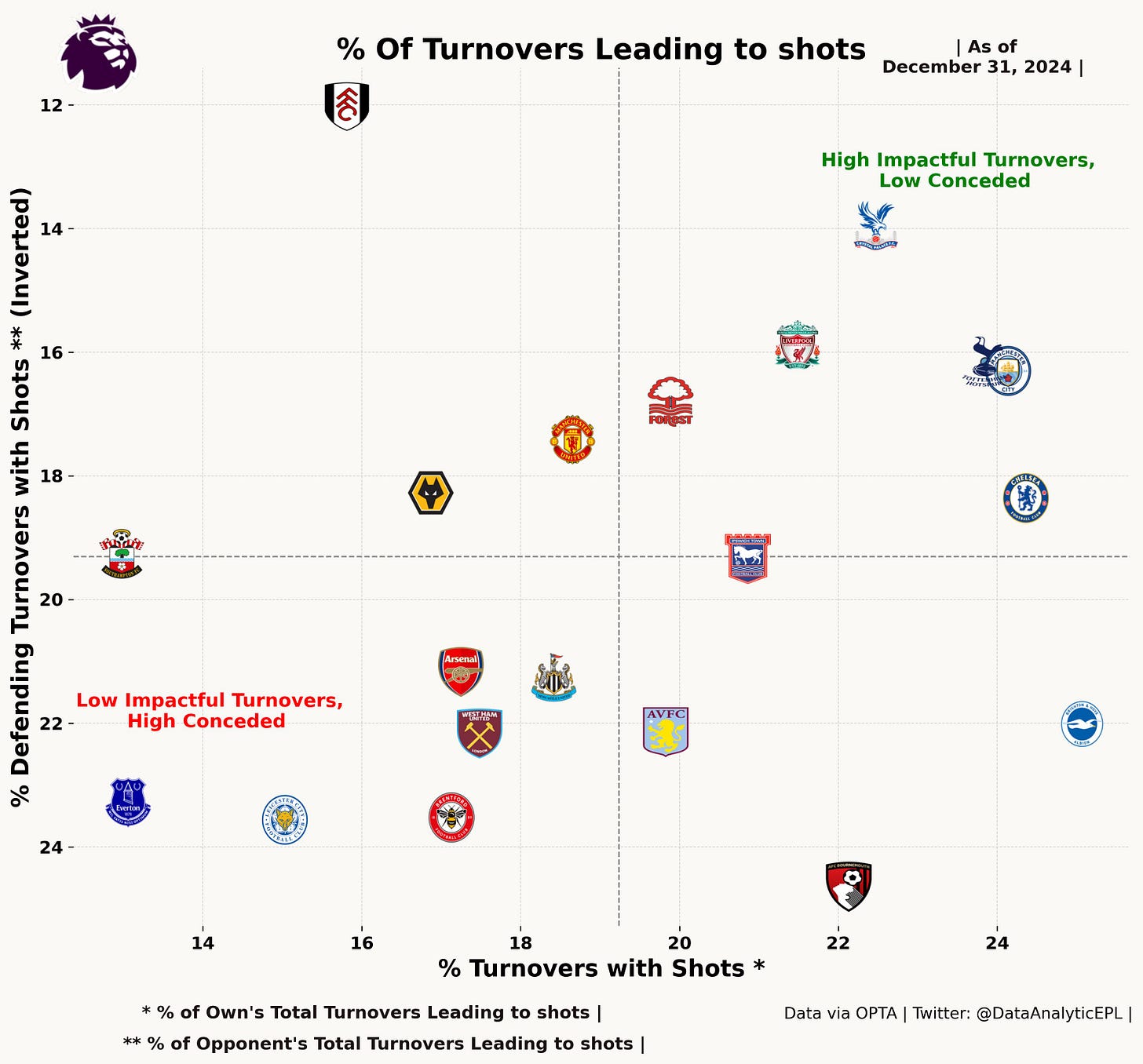

This mid-to-low ball-hawking results in the plays Liverpool are most known for.

👉 “Fast breaks”

Opta defines a “fast break” as:

An attempt created after the defensive quickly turn defence into attack winning the ball in their own half (counter attack)

Liverpool lead the league in fast break shots (1.26/90) and are second to Tottenham in fast break goals (0.50/90). Man City are down in 13th; Arsenal are in 16th; Brighton are in 17th. Because this is predicated on winning the ball back in your own half, it can be hard to manufacture these opportunities as a higher-possession team. You may associate this more with a muscle-and-run team like Forest. Liverpool still manage.

While we should keep that number in proportion (it’s just 1.26/90), that number doesn’t include counters started ahead of the halfline, so it likely understates the advantage.

There are a few ways that they do this. For one, Gravenberch has turned into a star on these from the double-six role. Per PFF:

Gravenberch’s standout trait this season has been his ability to kickstart transitions. His 90.2 ball carry grade (a summation of Dribbling, Carrying and Tackle Resistance) is 1st among all players in the Premier League.

The first element is the quick carry and forward pass like this.

But the second is the timing and focus on box arrivals.

Arsenal fans can get frustrated at the sight of somebody like Ødegaard or Rice turning down the chance at a counter, but this is often simply because they are counting, and see a 2v5 or the like. Still, if you’re going to have a slower driver like Ødegaard, that increases the need for runners elsewhere.

Arsenal do all-hands-on-deck defending, where everybody — Martinelli, Havertz, Jesus, Saka, etc — is a helper. In a practical sense, this makes Arsenal virtually impenetrable, but it also usually means they are deeper when the ball is won. If, say, your two highest players are Havertz (who is incredibly engaged in the block) and Ødegaard (who isn’t particularly fast), your countering threat is weakened.

This is having an impact.

This shows the other, less-covered issue: this year’s midfield configurations have been too vulnerable when defending the counter.

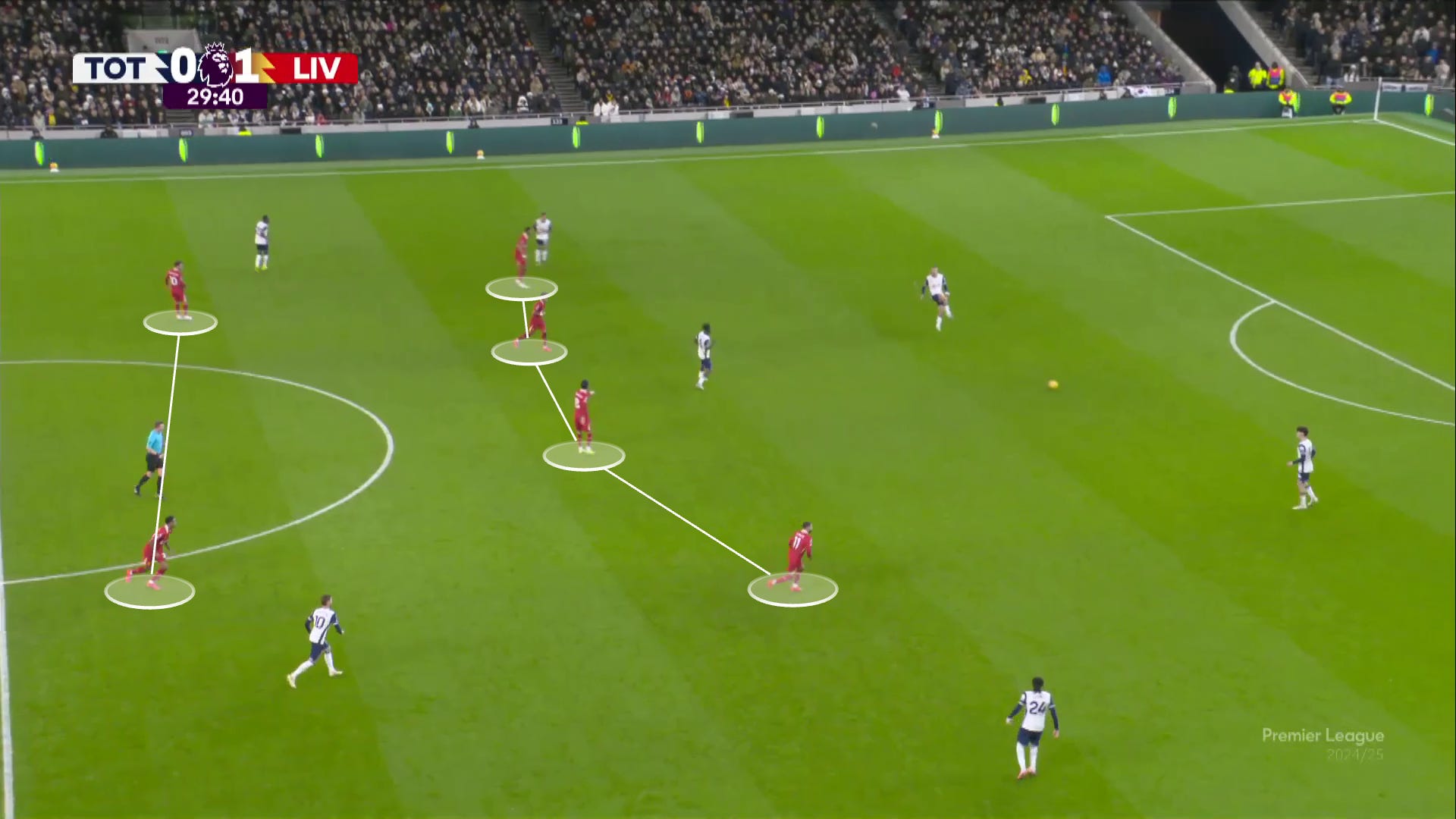

In contrast, when a counter opportunity is “on,” Gravenberch sees a fuller suite of options available, and Liverpool always — and I mean basically always — have three runners arriving in the box at the same time.

This Gakpo shot was a nice strike, sure, but it’s hard to see it finding a lane if the backline wasn’t getting pulled around by all that activity.

In another eventual goal, watch Salah and Jota cheating up here.

Look at Salah on the top of the screen here. Straight relaxing — until he isn’t.

...and again.

In the box, Liverpool often score when a stable triad of attackers burst forward on a cross.

…and this will look like the gif of that opportunity, but it’s a different one: Trent hitting toward a trio for the first goal against Spurs.

Can Arsenal improve here? Sure.

You see the subtle difference in a chance like this, which is basically well-handled by all involved. But picture this with Martinelli a bit lazier on the weak side, already ten yards up.

The darkest period for this was when Rice had to help the #6 deep, and there wasn’t a right-back who could offer high-and-wide help, so Havertz went out there from the #9. This preoccupation of the LCM, the low play of the right-back, and the wrong-footedness of the left-back, left the box open for too long.

Especially when playing with Kai, Jesus and Merino have helped considerably.

Jesus has been flexible, sure, but has been disciplined at staying central, giving reference runs for Kai and others (like Merino) to interact with. Here’s every zone getting covered on a Tierney cross, with Merino in that high-LCM role.

Here’s the “strikery midfielder + midfieldery striker” connection paying dividends again. Kai scored this from LCM. Including his work for Germany, I counted 11 G+A across competitions when playing off somebody in the front.

It’s hard to picture this going in without the additional presence of the LCM and the 9.

…and the Merino/Jesus runs here, followed by the Martinelli strike, looked every bit as good as those Liverpool highlights.

With some fresher legs, better dynamics, better game-states, and better form, Arsenal were able to sneak more steps in the good December games. Jesus was looking a little Salah-like on this one, opportunistically pushing forward before the ball was secured.

…and with the lead in tow, Martinelli was on a mission against Brentford. Look at him starting his run before Raya secures it here.

Despite the number of Liverpool attackers on the counter, Arsenal have 44 offsides to Liverpool's 27 — which, again, slows down the game some more.

Some general thoughts here:

It is in the team’s DNA to defend as a team. That said, I think Timber in particular can handle himself. Whichever winger is on his side should walk a little more, and creep higher up in case of a ball-win.

When preserving the lead, I like the idea of putting (whoever) at LW and then fielding a midfield of Rice (#6), Merino (LCM), and Havertz (RCM) — with Martinelli as the striker, making runs from the circle.

I’d still like to find other opportunities for Martinelli to defend in the front-two, even if it’s just rotating with the striker. I love the idea of him being the highest player when the ball is won.

We could really use another runner.

👉 Set pieces

Arsenal have been a lot better than Liverpool at attacking set pieces.

This gives you a sense of the dichotomy:

Arsenal: 0.5 set piece goals per 90, 0.16 fast break goals per 90

Liverpool: 0.11 set piece goals per 90, 0.5 fast break goals per 90

Elsewhere, according to WhoScored:

Arsenal: 10 set piece goals scored, 5 allowed

Liverpool: 2 set piece goals scored, 3 allowed

Liverpool are also +5 on penalty kicks (5 taken, 0 conceded), while Arsenal are an even 2-2.

👉 Subs, injuries, and second halves

Slot has been good at dialing down the physical load of playing for Liverpool, and that is likely related, at least tangentially, to their cleaner injury record. He does have an older squad, and things can change quickly.

For Arsenal, it’s not just about the number of injuries, it’s been about how they’ve cascaded in timing and position. Calafiori, Zinchenko, Tierney, Tomiyasu, Rice, Merino, and Ødegaard missed the North London Derby. A team that previously had no left-backs now seems only to have left-backs. Sterling went out right before the Saka injury, followed swiftly by the Nwaneri injury. Fuck.

I thought it was worth checking out how the subs have impacted this, as well.

My answer?

Not much. Arsenal and Liverpool make a fairly similar number of subs for a similar amount of minutes.

“Post-hoc” analysis on substitutions is always tempting but almost always foolhardy. There can be questions about the physical demands of certain roles at Arsenal, and I’m concerned about players like Timber getting overworked by necessity, but I don’t think subbing is really the problem here.

It’s also common to think that Liverpool simply have more attackers to throw on than Arsenal. I thought this too before writing the article. In fact, it’s pretty even:

Liverpool: Salah, Díaz, Núñez, Jota, Gakpo, Chiesa, Elliott (?)

Arsenal: Saka, Martinelli, Havertz, Trossard, Jesus, Sterling, Nwaneri

Both teams look thinner up there than the likes of Bayern, Real Madrid, and Manchester City. Liverpool’s advantage over Arsenal is largely in the attacking midfield spot, where Arsenal boast a better starter but less breadth.

When you sort it by percentage played, there’s a clearer picture.

Save for Alisson, Liverpool’s distribution of minutes looks pretty much like Slot’s ideal. Arsenal’s looks fairly close to Slot’s ideal, too :(.

I’ve had some issues with Arteta’s minutes distribution in previous years, but these problems strike me as more circumstantial than anything. Ødegaard went out in internationals, Merino got hurt in his first training, Timber is coming back from a flukey ACL, and Saka/Havertz/Rice all came back from the Euros looking more fatigued than usual. I didn’t like how long the Merino saga dragged on, and we may be repeating that in the January window. But sometimes shit just happens. It happens more thanks to the schedule.

“I think it is better if we play less football. Not only because of the physical strain, but also because it reduces the quality of the game. The big problem is that you never have time to train during a season. You are only recovering.”

I’d add two notes for the future:

As the minutes suggest, I think Gravenberch has played himself into near-indispensability. While Jones and Mac Allister can cover many of his qualities, there’s a bit of verve to his game that would be difficult for Liverpool to replace.

Liverpool were much better-situated to cover an injury to their keeper than Arsenal would be with ours’. And it showed. Raya and Timber have turned themselves into high-tier dependencies.

So, you take these three factors:

Liverpool playing a style where they can “rest with the ball”

Liverpool simply having better fortune with availability (perhaps related)

Liverpool having more depth in a) pure speed and b) advanced midfield

…and you have a recipe for better second halves. Arsenal are currently top of the “half-time table” (you’ll never sing that), but 11 points behind in the “second half table.”

This coincides with the arms race in the Premier League, in which a 10th-place team like Brighton can throw on the likes of Mitoma, Minteh, and Rutter in the second half. At a time when fatigue rules everything around us, the level of talent and athleticism entering games late is at an all-time high.

…and that has caused six more dropped points from leading positions.

Six points is the difference in the table.

👉 In conclusion

Some final thoughts:

It has a lot to do Mo Salah. If you are a Liverpool fan reading this, and bristling at the idea that Salah is carrying you to a title, please … don’t. It doesn’t invalidate the contributions of others, and I promise that if Saka was healthy and doing that for us, I wouldn’t lose a moment’s sleep.

It also has plenty to do with [luck/misfortune/getting fucked], whatever you want to call it.

Otherwise, the central thing is this: Liverpool just score more goals than Arsenal. To achieve this, they take more shots. All solutions at Arsenal should be geared toward generating ~2-3 more open play shots per game.

Arne Slot deserves credit. Most specifically, he deserves credit for a) his vision for Ryan Gravenberch and b) how Liverpool distribute energy, tailoring it to the highest-impact moments.

The dispensation of energy — fatigue, knocks, injury, etc — presides over every aspect of the game these days like a demigod, in ways that we can barely imagine. Liverpool have been both smart and fortunate on this front.

Arteta did the energy management thing very well last year. He played the long game and was generally fortunate with his stars. The calm, pragmatic style of the first few months helped the team return to full health in the closing months, which led to the explosion in goals. He just hasn’t had the ability to tune the dials this year. Everything felt “out of necessity” from the jump.

The issue moving forward? The long game generally worked there — and it’s working now for Slot, who didn’t have to sacrifice much to play it. A busy schedule is ahead, Saka won’t be back soon, and there’s no real break in sight.

By not moving too quickly into the final third, Liverpool preserve space for Trent to hit balls in behind, and for their attackers to run. This basically means they play generally slower, then suddenly quicker than Arsenal.

I do believe that Arsenal can recycle back some more, and be a little more patient about advancing to the final third. Teams basically allow those advancements to happen anyway, so Arsenal should wait for more tangible advantages to accumulate to push it forward. This will help maintain the space to shoot when the final action is nigh. That said, it shouldn’t be at the level of Liverpool; we don’t have an analogous deep passer to Trent. Relatedly, I think Raya goes long a little bit too much when there isn’t an advantage up there.

Arsenal should consider real tweaks to the ‘rest attack’ to get better runners up high when the ball is won. The most aggressive form would be a front-two of Havertz and Martinelli. The more likely tweak would just be Martinelli playing the “late-match” version of his game at all times: for now, that means cheating up from right-wing. This has an anchoring effect, pulling the defensive line apart, and giving time for more runners to arrive on the scene.

Through delays, fouls, and a reliance on the long-ball, Arsenal open themselves up to variance more than Liverpool. Overmatched teams keep the ball out of play in the hope that the spikes of variance carry more weight in the final equation. Arsenal do this now as the presumably better team. I’d suggest no changes to the corner routines, which are obviously working. The other delays may be necessary in those games with a short bench, or even make sense in a vacuum; but pressure is cumulative, and there is a psychological impact to wave-after-wave of attack.

A quote on that: “Look at a stone cutter hammering away at his rock, perhaps a hundred times without as much as a crack showing in it. Yet at the hundred-and-first blow it will split in two, and I know it was not the last blow that did it, but all that had gone before.”

The way I’d phrase that is this: especially against weaker sides, Liverpool have given themselves more opportunities to prove their superiority.

Liverpool doing well doesn’t invalidate the idea of pinning teams, or the strength of threading play through the side before attacking the middle. But as we’ve discussed, it doesn’t have to be either/or; it can be both/and.

Few players can make you question your squad-building priors like Gakpo and Gravenberch. The fees weren’t really the question — after Olise, Gakpo was second on my winger list for Arsenal before he was signed, and both he and Gravenberch had plenty of talent to warrant that kind of expenditure. What didn’t feel right were the questions around squad composition and need: were they the exact right signing at the exact right time? Liverpool seemingly had enough forwards and midfielders then. In 2025, the logical conclusion may be: “who cares?” They are young and good, they were capable of being great, and if they flop, the opportunity cost wasn’t mammoth — you can flip ‘em for €25m. In the days of never-ending fixtures, you may just have to budget for an extra “mid-tier” signing or two. Elliot Anderson is playing as I type this — he was €41m after 13 top-flight starts. That sounded very steep at the time, but it looks like a sound investment to me.

A system is only as strong as its players.

Arsenal somehow play again today.

All is still to play for, despite it all.

I hope you’re well.

❤️

I love this sort of deep yet approachable analysis so much. Thanks for this, can’t wait for more (alongside a January signing…)

Great read this ✔️