Why Arteta values unpredictability, and how Zinchenko helps him achieve it

Atomic Habits is the exact kind of airport self-help book that I usually skillfully avoid. In a moment of weakness a few years back, I picked it up and read it in one sitting. Parts of it have stuck with me ever since.

One of the little takeaways was about how good habits only build when they’re congruent with a sense of identity. As an example, if you’re the type of person who says “I’m not good with names,” that’s an identity you’re creating, and a good habit (in this case, remembering names) is unlikely to glob onto that sense of self. If you tell yourself, “I’m working really hard to get better with names,” you might have a better chance.

Likewise, when looking to change, it’s human nature to start with the desired outcome. But it’s most effective to start with identity, and then build processes and small wins that prove it, and not the other way around. Here’s how it’s visualized in the book:

Which brings us to Mikel Arteta. If you watched All or Nothing, this was a recurring theme. As obsessed with tactics as he is, he’s even more obsessed with team identity. Memes aside, he’s constantly urging his players to play bolder, braver, more confident — and yes, with passion, clarity, and energy.

As he told Sky Sports when he took the job:

“Without an identity, you cannot plan and you cannot convince a player to do what you want.”

After long months of progress and change, his vision seemed to reach a coronation of sorts in the closing minutes against Liverpool, holding a lead against a vanquished giant, screaming at his team to stop sitting back and play higher, all within earshot of Jürgen Klopp.

In pursuit of unpredictability

Arteta wants to play dominant, possession-based football—and looks to lead a team that is confident enough to do it against any opponent. But this year, as the foundational level of quality improved, he has sought to add a dimension to the tactical solidity. Back in the spring, a word started popping up more as he began playing Xhaka more advanced:

“Sometimes you have to take players from their comfort zone and open a different door to explore how the team will react [and] what the opposition will do when you do certain things. Then it’s more unpredictable because if not, it’s pretty easy to prepare against the same opposition.”

As the weeks went on, the word popped up some more:

“We have to make things quicker, sharper. We can be more adaptable, we can be much more unpredictable, we can have much more flexibility and we can be much more consistent throughout games to maintain that level.”

Then the summer came, and it was easy to see that philosophy extend to the new signings. The new striker, Gabriel Jesus, has a claim as the most fluid player at his position in the world. The new attacking threat, Fabio Vieira, excelled at Porto in a positionless role that roughly translated to “wherever I please, thank you.”

Then came Oleksandr Zinchenko, an adapted number 10 who spends as much time roaming the midfield as … a midfielder, I guess. In the Arteta press conference to follow, the word showed up again:

“That versatility is something that is going to be important for the team because we have players in that position who are more specific full back so I’m really happy. To be more unpredictable is obviously important and that is why we have recruited those players.”

If you want the outcome (we will score more goals) you need to adjust the team identity first (we are versatile and unpredictable). Arteta sought to add players who had these qualities at the core of their game.

Since then, it’s shown up on the pitch.

How flexibility won the game against Wolves

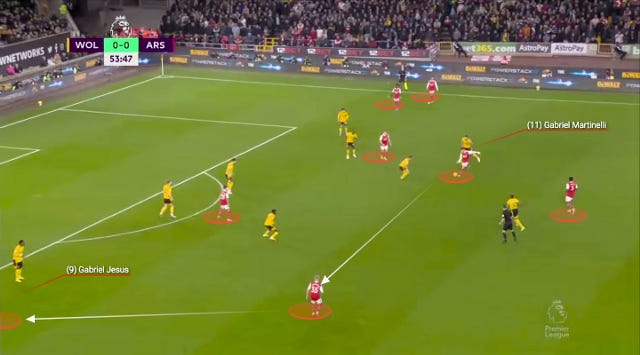

Wolves had a plan to concede possession and mirror-image the Arsenal attacking 2–3–5 shape with a 5–3–2, which made it difficult to achieve overloads. After long periods of control, occasionally interrupted by bursts of counter-attacks by Wolves, Arsenal got on the scoreboard twice in the second half. Both goals were due to positional flexibility.

In the first goal, Martinelli had taken a throw-in from Zinchenko and freelanced all the way down the right half-space. Last year’s RCB, White, is holding width on the right with Saka, Ødegaard is joining the advanced line, Vieira is at the 9, and Jesus is out wide left. Martinelli plays the ball to mezzala-ish Zinchenko…

…Zinchenko then plays to Jesus, who darts laterally and finds Vieira for the “Xhaka cut.” Saka and Ødegaard crash the box and Arsenal goes up 1–0:

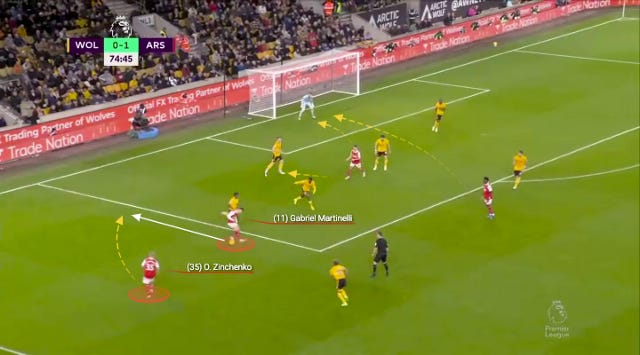

The fluidity also played a part in the second goal.

In this sequence, Martinelli had sprinted from the corner flag after securing the ball, and back-heeled it to an overlapping Zinchenko:

So much is happening in the above screenshot: Vieira made multiple striker-like cuts, holding defenders; Saka was creeping over to a central position; Ødegaard crashed the box from out-of-picture. Jesus, likewise, is so wide-right he’s not even on the screen. Oh no! Everybody is out-of-position!

Because of all of this activity, no one could close down on Zinchenko, who had time to calmly dribble to the net and cross it in. Martinelli had one blocked before the captain scored his second. 2–0.

This unpredictability is paying dividends. As the team gains comfort in these constant rotations, and Zinchenko returns from injury and takes the reins of the position, let’s further our understanding by comparing him to the rest of the cohort.

How does Zinchenko compare to the other options at left-back?

In Zinchenko, Arsenal signed one of the safest progressors in the world. Among full-backs in the Premier League last season, his 77.55 passes per 90 were tops of all, while his pass accuracy (89.3%) put him first among all left-backs.

To compare him to Arsenal’s other options, here is some data I pulled from all of their appearances at LB so far this year. Caveats apply, as the sample size is somewhat limited, and competition levels vary (Tierney has probably had the easiest run of opponents so far).

Here are their respective heatmaps:

And here are some baseline, LB-relevant statistics:

Of note:

Zinchenko passes more, and more accurately, than either of his colleagues. He also receives more passes than either.

He wins 58.9% of his total duels, compared to 48.1% for Tierney and 41% for Tomiyasu.

He is much more likely to recover the ball upfield, but has fewer overall interceptions.

Surprisingly, he initiates fewer offensive duels than either, which may be a product of him being more likely to avoid direct challenges.

The numbers seem to suggest that Zinchenko is the superior option at left-back. But there are still factors in support of the others, among them: Tomiyasu zeroed out Salah, who went on to score a six-minute hat-trick in his next game (though Tomi struggled when pressed by Leeds). Tierney is also in good form and adapting to the inverted role (though he’s having to override some bombing instincts to do so).

The questions are more about Zinchenko himself. He had some lapses against Wolves, particularly late, and teams seem intent on funneling counters to his side of the pitch. How big of a deal is this? To what degree does he make up for it with his contributions in possession? Did my man just have a bad burrito or something?

To answer these and more, let’s look at how Zinchenko approaches different aspects of the game.

🍗 Zinchenko in the build-up

Within twenty minutes of his return against Chelsea, we were treated to the Full Zinchenko Experience.

At two minutes, Chelsea is running a narrow-high press—across two managers, they’ve run the highest advanced pressure in the league this year. Instead of standing on the touchline, Zinchenko is scanning his surroundings, and finds a fresh patch of grass to split the pressers. Ramsdale is bold (and talented) enough to give him the ball…

…and in one pass, the press is broken. Zinchenko carries it to the center circle, and delivers a pass to Ødegaard that wouldn’t be available if he was a wide full-back.

Afterwards, Ødegaard delivered the ball to Saka on the wing, who took on Cucurella for a foul. They were awarded a free-kick on the edge of the box only 9 seconds after Ramsdale had it on the other end, and the ball never left the ground. Not bad.

A little bit later, he initially shows in a similar inverted spot, but then drags Sterling all the way towards Saliba…

…and the vacated zone is now wide-open for Gabriel to receive the ball, carry it forward, and kick off the attack. Gabriel is great in these moments.

Finally, let’s see what happens when Chelsea relaxed a bit.

At 18', Gabriel is carrying the ball with less direct pressure being applied, so Zinchenko holds space out wide. That leaves space for someone to drop in…

…and both Xhaka and Jesus identify the opening and go to drop down, but Jesus (unsurprisingly) wins the race to fill the vacated midfield spot. As he does, Sterling is caught in the middle, and Zinchenko sprints up the touchline…

…Gabriel ultimately forgoes the pass to Jesus and plays it directly to Xhaka. Martinelli runs into the striker spot that Jesus left behind, and Azpi is now forced to decide whether to run with Zinchenko (wide) or Martinelli (narrow). Zinchenko gets the ball and kicks off an attacking sequence.

This team can often rely on Partey’s press-resistant passing to an extreme degree. When Zinchenko joins him in the midfield, and uses his full battery of solutions to progress the ball—including standard inversion, rotations with attackers, off-ball-movements that drag defenders, and change-of-play balls—the chances of Arsenal getting stuck for long periods of time become exceedingly small.

🍗 Zinchenko in the final third

Playing against Wolves was an altogether different beast. After a showdown with the highest-pressure team in the league, they played a fully parked bus at Molineux: Wolves allowed 27.29 passes per defensive action, which was the lowest activity Arsenal has faced aside from PSV.

Because of this, progression was not an issue: Wolves allowed it without much bother. Their gameplan was to a) mirror the 2–3–5 to keep the ball in front of them and prevent overloads, b) surround Partey to cut off dangerous passes, c) play with higher challenge intensity on the Arsenal left to try and dispossess and start counters there, and d) largely allow the White-to-Saka touchline pass to happen.

This had many effects, including Zinchenko touching the ball a lot more than against Chelsea, with many of them floating across zones instead of up the left: he sent or received a total of 60 passes to the likes of Saliba, Partey, Ødegaard, White and Jesus.

In the final third, this meant trying to unsettle the back-5 shape with creativity and interchanges—as they did in both goals above.

These switches showed up early.

Five minutes in, with Xhaka still on the field, Zinchenko delivers it to Martinelli on the wing and immediately underlaps…

…While Martinelli is still given little space by Semedo, he’s at least ensured a one-on-one without midfield help. He cuts back and bangs a cross into Jesus, who controls it and nails it in for the sweet goal that was ruled offside.

The interchanges only increased with Vieira’s substitution.

A little bit later, he can be seen holding the wing with Vieira dropping deep, and Martinelli playing in the channel — where he can sometimes act like a shadow striker:

Against an opponent playing a compact 5–3–2 (that could morph into a 5–4–1), this constant barrage of activity eventually unsettled Wolves and created the conditions for the 2–0 win.

🍗 Zinchenko in the counter-press

Conversations about Zinchenko’s defense can sometimes be reduced to how he fares when tracking back, but there are dimensions to it all.

When Arsenal loses the ball, they spring to life in their 2–3–5 rest defense. Particularly in the immediate counter-press, Zinchenko is effective: he’s 99th percentile in tackles in the attacking third, and 71st percentile in tackles in the middle third. He’s decisive and aggressive, and if the tackle doesn’t get home, he can usually lean on the player to slow them down.

He disrupted a few possible Chelsea counters this way:

In the last two matches, he’s also been good at offside-trap coordination with the fellow members of the backline.

There is one caveat—in standard pressing, he can sometimes look to make challenges that aren’t “on” against the opponent’s wide players. This can lead to him stuck in the middle: meandering way upfield, not far enough to get home with a challenge, but also with little chance of getting back.

🍗 Zinchenko tracking back

Speaking of getting back, this is where Zinchenko has legitimate issues. Compared to attacking midfielders and wingers, his speed is not an advantage—and his baked-in aggression can sometimes lead him to taking circuitous angles on balls.

In the midst of the dominant early Chelsea display in possession, he misjudged a throughball from Sterling to Havertz. As he went out to try and intercept it, it got around him and Havertz was able to … try some weird half-cross thing that went nowhere.

Against United earlier in the year, he took a wrong angle to close down the ball up the middle that Saliba probably had covered, leaving Antony free behind him.

His eye for the ball plays wonderfully in the other thirds, but leads to struggles when tracking back.

🔥In conclusion🔥

The peak-end theory is a psychological rule in which an experience is evaluated and remembered based on the peak (most intense) point of the experience and/or the ending of the experience.

In the memory of a football match, one missed chance or one clumsy turnover may outshine 40 chain passes that made the difference. (I’d urge you to keep that in mind when reading those player rating articles that come out right after the whistle.) In a low-scoring game based on high-impact moments, this is to be expected.

Watching the Wolves game again for this piece, I kept waiting for Zinchenko’s mistakes to come, and the memorable ones showed up late: at 83', he slipped while marking Traoré. At 88', he got cute in the midfield, leading to shot on goal and a delightful Ramsdale scolding. Both of these happened with substitutes warming up, in a game he reportedly had food poisoning.

But let’s not delude ourselves. While a dangerous loss-of-possession is uncharacteristic in a career marked by security, this is likely not the last we’ll see some lapses in the defensive third, particularly when tracking back. How much does this matter, really?

Here’s one way to look at it:

Arsenal manages possession at a rate of 58%, a number Zinchenko helps increase.

During that 58%, they face the third-lowest pressure lines on average, meaning the ball is usually in advanced areas.

When out of possession, Arsenal runs the second-highest intensity line, working to keep the ball on that side of the field.

Because of that immediate pressure, Arsenal gives up the fewest progressive passes in the league (15.6/90) and the second-fewest long balls (32 per 90).

They’ve also climbed the ranks on offside-trapping, ranking second with 2.71 per 90.

In all, only City holds their opponents to fewer touches in their own defensive third.

In other words, Zinchenko spends a low percentage of his time actually fullbacking, and Arsenal does everything in its power to make sure the shaky moments are few in number.

For example, both Chelsea and Wolves sought to flow transitional balls to Zinchenko’s side. The results of those positional attacks down the opponent’s right side? A total of 0.01 xG across two games:

When they do get through, it’s ultimately not just about Zinchenko. Like Klopp and Guardiola before him, Arteta does not operate on the hope that his center-backs have these covered; he operates on the assumption they have them covered. This can be a risky wager when they’re not in top form (as you see at times with Liverpool this year), but by snuffing out a couple moments a game, it allows everybody to play with the boldness that is expected ahead.

While it’s natural to fear a repeat of the United game on the counter, that game may have turned out differently with any one of many improvements, including: more solidity on the offside trap, Partey at the 6, Gabriel’s improved form, and more luck with the VAR. The question of how a Gabriel/Zinchenko pairing would fare against a Salah remains slightly open, but Chelsea and Tottenham's attackers were ultimately held at bay, and my guess is Arteta sends early help like he did with Xhaka.

As perspective: in Zinchenko’s last two starts, Arsenal has conceded a total of three shots on target.

--

It’s easy to see why Arteta wanted a natural inverted fullback so badly. In this role, Zinchenko helps Arsenal create new pentagons, push the 8 up the field, ensure more fluidity for all, control the center of the pitch like a chess board, and counter-press more effectively.

Zinchenko embodies the identity of boldness, versatility, and fluidity in possession that Arteta has been seeking. He is active on the counter-press and helps create a left-side that is press-resistant and confident. Pivotally, to the theme of this post if nothing else: he helps make Arsenal unpredictable.

Happy grilling everybody.

🔥

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — -

Support this work

If you’d like to support this work coming out every week, I recently started a Patreon. I am so appreciative of those who have signed up at £2–3/mo to keep this series rolling.

Thank you all.