Adventures

Breaking back-fives, what numbers have changed (and what haven't), how Eze differs from Ødegaard, Saliba in midfield, scattered notes on Rice and Gyökeres, and more

“No, no! The adventures first! Explanations take such a dreadful time.”

— Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

Let’s get into it.

👻 Exorcism

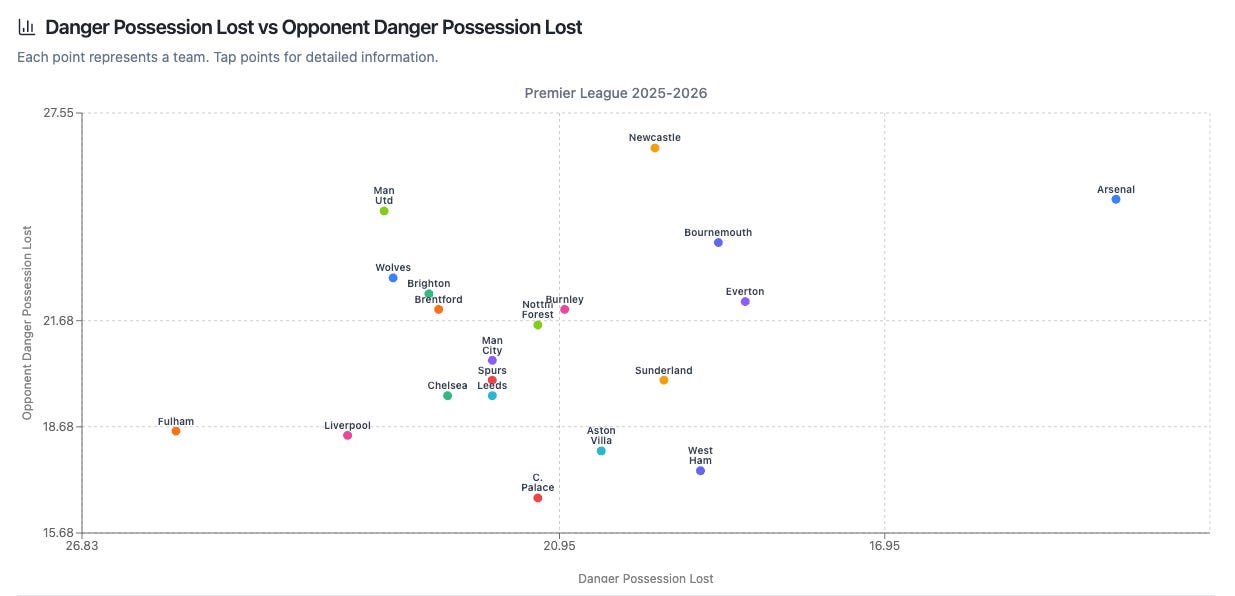

It can be said that Arsenal did not lose the title against Liverpool or Manchester City last year, but against the likes of Newcastle, West Ham, and Everton. In fact, since the arrivals of Declan Rice, Kai Havertz, Jurrien Timber, and David Raya, Arsenal had gone 22 games unbeaten against the so-called “big six,” but last year alone, dropped 32 points against teams fifth or below in the table.

This was in keeping with wider trends. Last February, I pulled this list of non-wins since the start of 2022/23.

Newcastle have been the ugly face of this struggle. In all five meetings where Arsenal failed to win, we hadn’t managed to score once.

As we wrote then:

But as you scroll through the results, you’ll be reminded of something else: how concentrated these losses and draws seem to be. While there are some explainable (and/or flukey) results … there is a collection of other results with similar characteristics. This includes the likes of Newcastle, Porto, Moyes’ West Ham, Dyche’s Everton, Villa, and Fulham. (Though Brighton are on the list, too, I think there are some mitigating circumstances there.)

We are mostly talking about Arsenal’s remaining scourge, aside from the injury bug: the well-coached, physical, mid-to-low block.

The most ridiculous whiplash was perhaps when Arsenal became the first side in Champions League history to score 7+ goals away from home in a knockout stage match, then came back to face, according to their own manager, “the worst team, maybe, in the history of Manchester United” and … drew 1-1. If not for heroics from David Raya and Declan Rice, it could have been even worse.

Speaking as a fan, I can live with performances like those against PSG, in which the team set up stellarly and gave themselves every chance to prevail.

I couldn’t live with another year of Fulhams or Newcastles.

What has made a team like Newcastle so imposing against Arsenal?

Let us count the ways.

There is simply an upper limit to how physical a team can be. If the spaces are kept small through mid-to-low-blocking, there is not really a way for your team to reliably be bigger/stronger than an opponent like Newcastle. You can only really hope to be on their level, which is hard enough.

With a bank of five defenders and a bank of four defenders, there are two difficulties facing an attack: central access is almost entirely cut off, and wide areas are consistently doubled. There are just a lot of big bodies standing in the way of shots.

When teams go long, the Arsenal press is essentially skipped.

Bouncing balls and delayed games will increase the impact of variance. Even if you play perfectly, there is a chance of certain bounces going their way. Because of how the spaces are occupied, the more defensive side’s mistakes are less likely to be punished because of all the coverage surrounding them. Meanwhile, the aggressor’s defensive mistakes are likely to happen in open space with less support around. This all benefits the underdog.

All these factors combine to essentially turn the game into a finishing competition. In such a contest, Arsenal are likely to have more chances, but they will be taken in packed boxes. On the other, a Newcastle will have fewer chances, but they will be taken in more open, transitional moments. (And, crucially, Newcastle have more natural finishers — one in particular.)

The first goal looms large.

But there is another thing at play, with wider implications.

This topic was recently touched on by Chelsea manager Enzo Maresca, in an interview that, for his sake, might have been a little too revealing.

“Sunderland played nine league games and they never used a back five from the start. Never. I watched them all, so we prepared for Sunderland with a back four.

“In the dressing room before the match, I told the players: ‘Guys, throw all of the Sunderland preparation in the bin.’ It’s so difficult to change plan in just 10 minutes.”

He also recounted a conversation with Ange Postecoglou, in which the Australian had talked about his dislike for the back-five.

“Then we played Forest — it was a back five, and I had prepared for a back four! I again told the team that everything goes straight in the bin because it was a back five. This is tough for players.”

Last season, Newcastle gave teams the template.

Why was this effective? The simplest explanation that I can offer is this:

Teams like Arsenal and Chelsea often give primacy to their “rest shape,” that is: not getting caught attacking in a shape that would be vulnerable to the counter; back-fives can require you to be more aggressive in your overloads, attacking in ways that bring jeopardy to this shape. (Throwing bodies forward for an overload is why Pep’s teams could be vulnerable to Conte’s counter-attacks, for example.)

Teams like Arsenal and Chelsea rely on playmaking full-backs to arrive at the backline and collapse the shape. Against a back-four, it’s fairly easy to get your full-back or winger isolated against the opposing winger. Against a back-five, these full-backs are more likely to be arriving in zones with defenders already waiting for them, making this more difficult.

This isn’t to say Arsenal didn’t find joy last season when things were clicking.

You probably remember when Gabriel Jesus decided that he had one mortal enemy, and that enemy was Crystal Palace. His streaking runs were coordinated with heavy ball-side leans. This Merino tilt resulted in a line-breaker for Ødegaard and a goal for Jesus.

Arsenal also dismantled Sporting shortly after Amorim’s departure. Many of the chances came from two clear patterns: (a) aggressive wide diamonds, and (b) multiple runners attacking the golden zone.

When comparing the challenge of facing a back four versus a back-five, a few things stood out, as we wrote then:

Against a back-five, more patience can be required. You have to keep probing for the moment to attack centrally, which is more likely to open up if you do your job. You can increase your odds with a pinning striker and a #10 floating on the same vertical line.

Against a back-five, it seems more important to gain a commitment through an immediate dribble to start a cascading effect.

Again, for posterity:

“You can increase your odds with a pinning striker and a #10 floating on the same vertical line.”

Interesting.

🧨 Breaking a block

Next, let’s cover a few of our takeaways from How to Make a Mid-Block Mid, written a year and a half ago, during the Porto days, starting with the simplest objective.

👉 It’s the personnel, dummy

You need passers, occupiers, and runners. The best teams have specialists who can flip it through the lines (Jorginho, Busquets, De Bruyne) and attackers who can arrive in key spaces at the right moment, with haste.

Or, in my plea from last February:

This summer, that means finally attacking this problem with the same clarity Arsenal showed after the Etihad loss. In that case, Arsenal refactored the squad with a clear purpose: better athletes, better duel winners, better defenders in space. Now, the next phase of adjustments have to come in the summer: more variety of passes, better dribblers, more speed, more attackers who can nail home a half-chance.

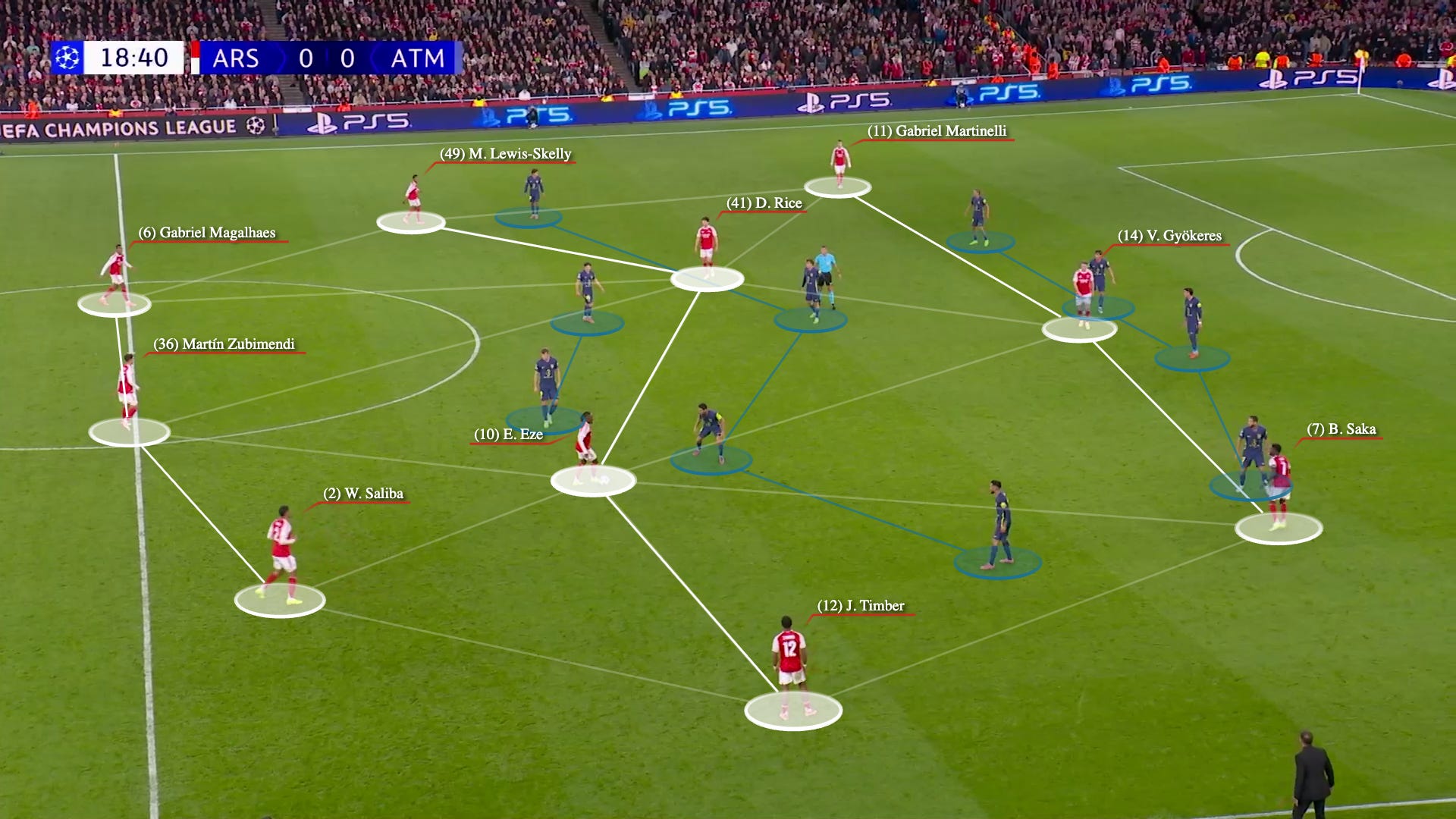

We see those passers, occupiers, and (usually) runners now.

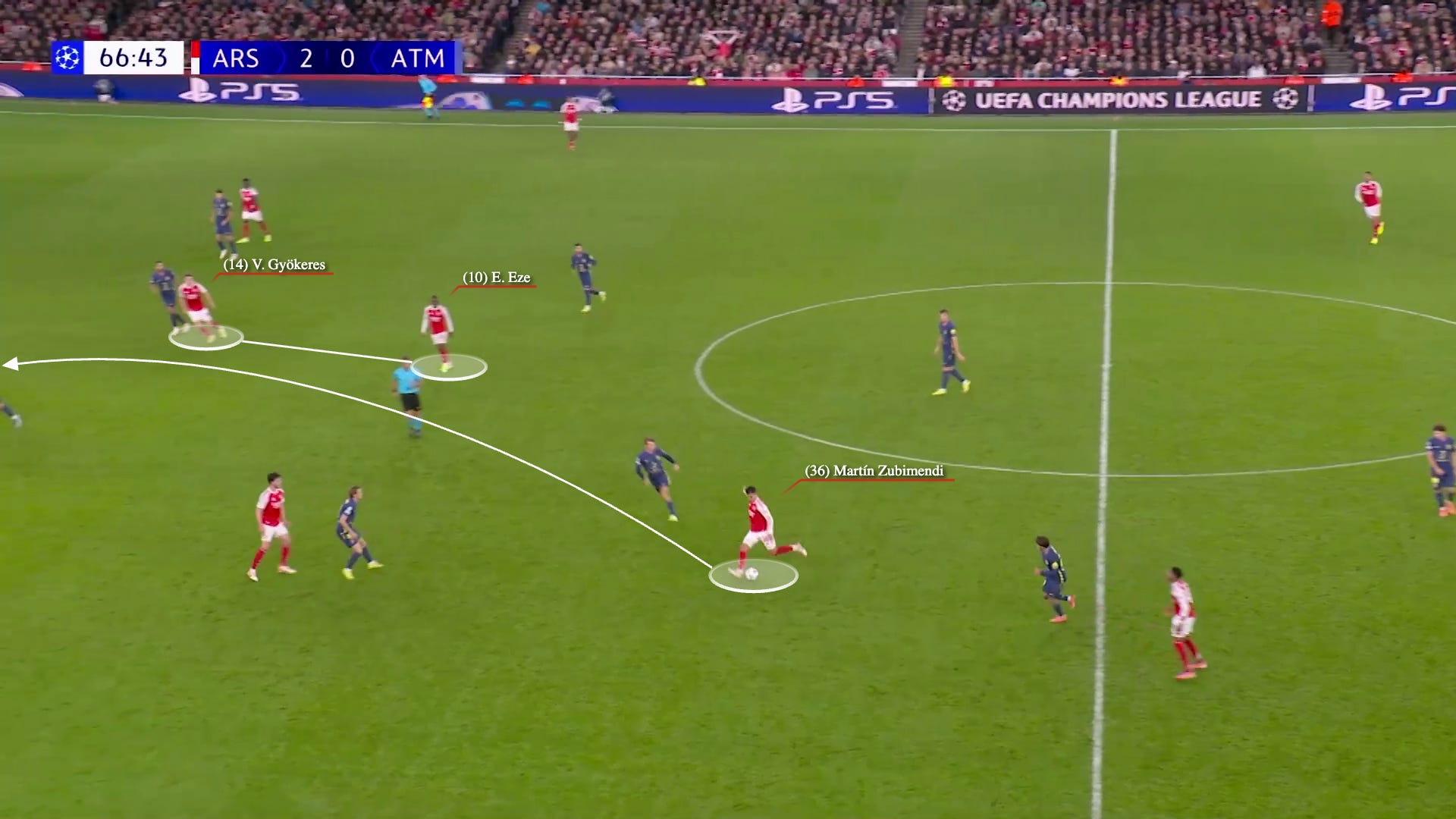

All three archetypes came through in this moment against Atlético. Zubimendi, the passer, is the first. There’s a specific kind of ball he hits that Arsenal would sorely miss without him. You can also look upfield for the foreshadowing: Gyökeres and Eze positioned on the same vertical line. Even against a back four, we’ve been seeing more of this, which can force awkward decisions once midfielders step out to press.

This seemingly simple pass goes a long way toward showing why Zubimendi was such a pivotal signing. Eze can deliver it too, and Rice is progressing, as we saw against Slavia Prague.

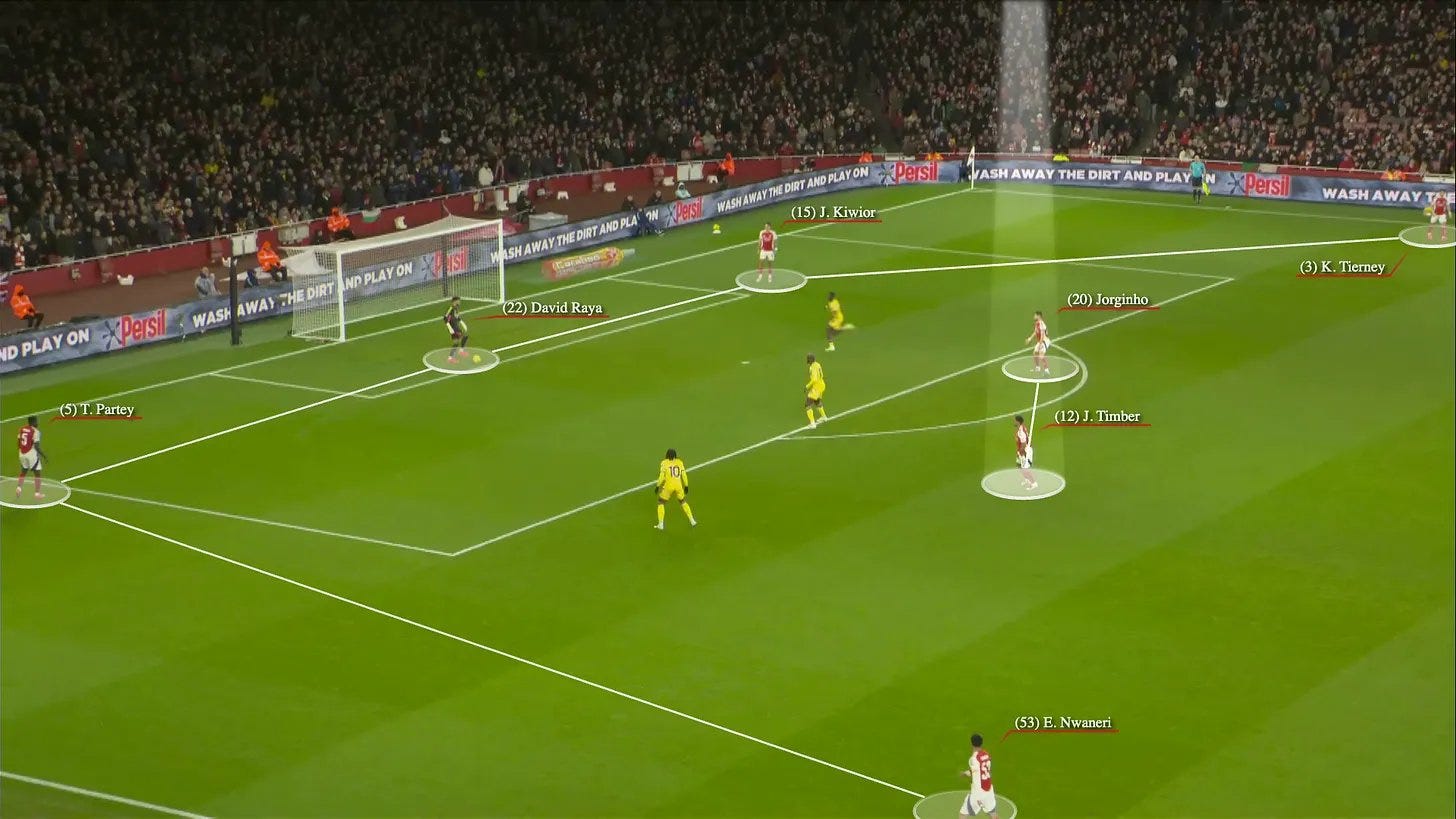

Otherwise, though, Arsenal haven’t had enough players capable of hitting this particular ball, and Jorginho vividly reminded us how impactful it can be.

When looking for a signing, the list of target midfielders narrows further when you ask for someone who can do it consistently with both feet, and it narrows even further (to only a couple of players in the world) when you add the requirement of withstanding the physical demands of being the deepest midfielder for a Premier League side like Arsenal. That’s the rare value of a player like Zubimendi.

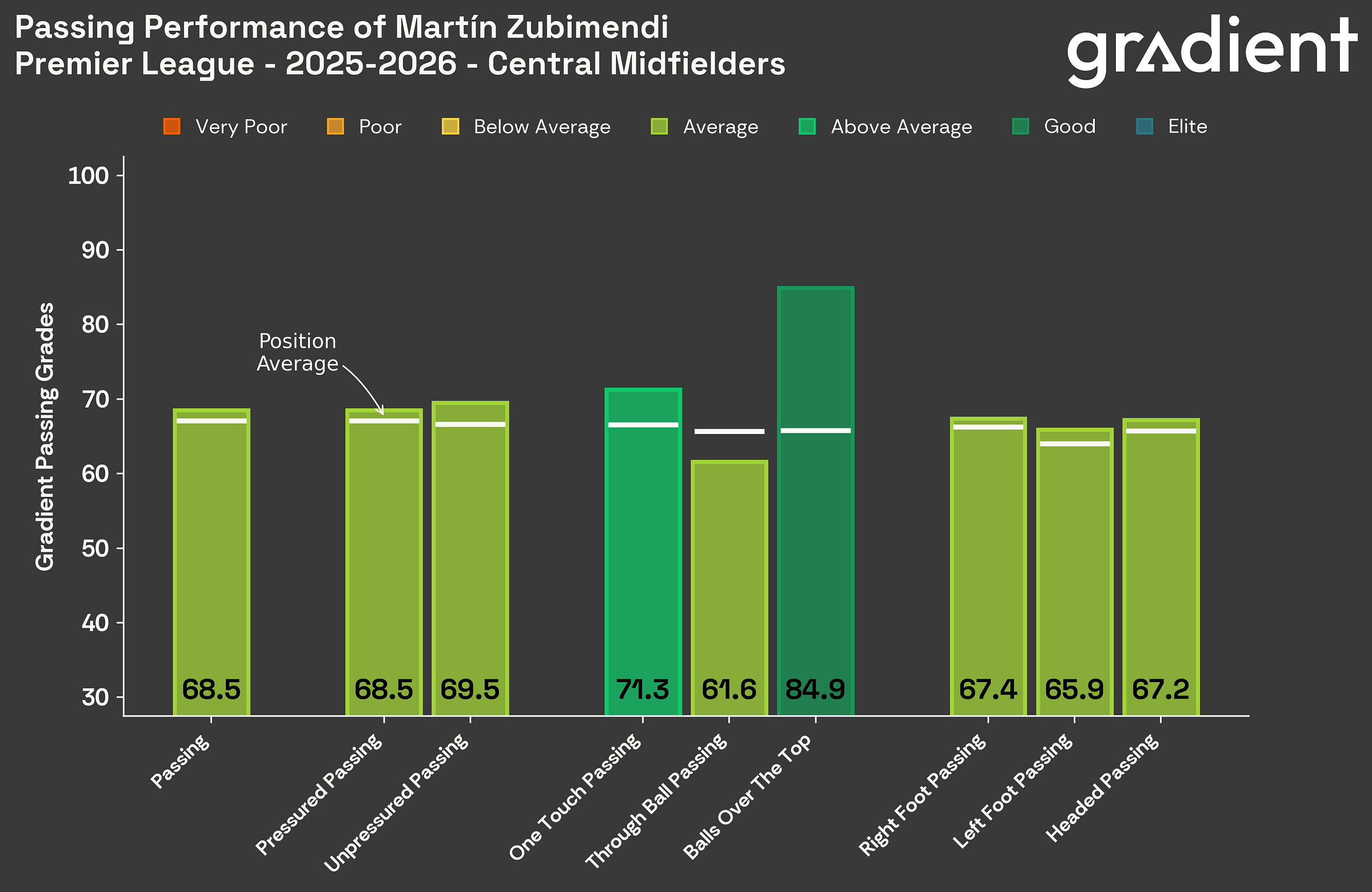

As shown here (in another excellent chart I pulled from Gradient), he scored quite well for “Balls Over the Top.”

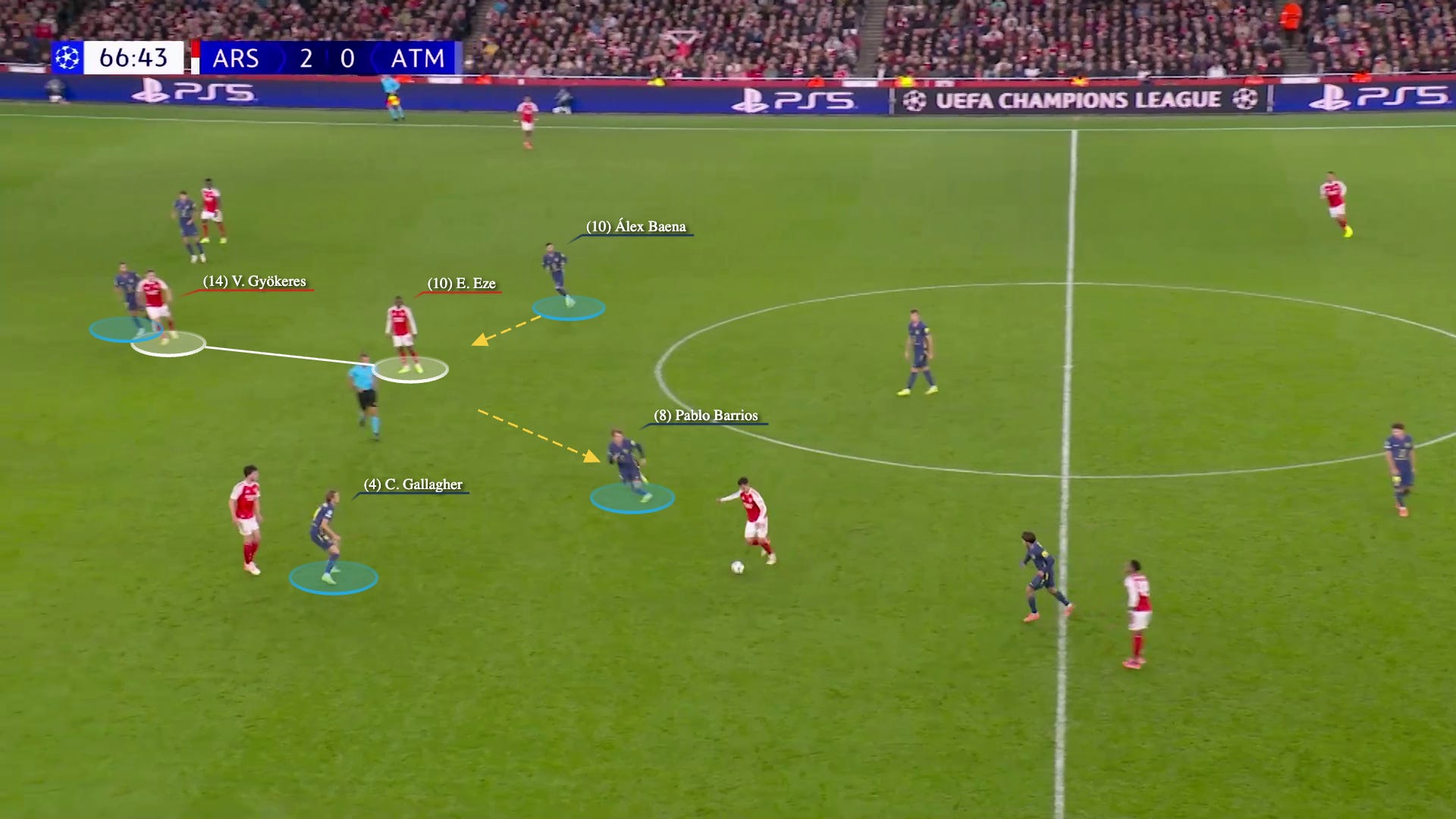

Next, we have the occupiers. This isn’t the cleanest example, but by Eze staying with Gyökeres while Barrios steps up, the corresponding movement is for Baena to follow him from the opposite side. As Baena is the left-most player in the second Atleti line, that’s a lot of ground to cover. Gyökeres does what any striker might and makes his run through the middle.

Then, runners. This, of course, is Martinelli’s calling card, and one that is especially apparent when the block gets pushed up due to game-state (in this case, Arsenal being up 2-0).

But he’s joined by two others: Gyökeres and Eze are both transition runners, and after a karate kick, Gyökeres breaks his Champions League seal for Arsenal.

I had the below clip saved as a clear example of the “passer, occupier, and runner” concept of breaking mid-blocks, featuring, who else, Busquets.

We’ll get back into that Eze shot later.

Onto the next pointer we outlined for breaking a tough mid-block.

👉 Attract the lean, switch quickly

Mid-blocks stay compact, meaning if you overload one side, they’ll shift toward the ball. Fast switches (low, driven passes rather than floated ones) create immediate openings before they can reset.

Switches, especially quick ones, create a “temporal advantage,” a two-or-three second window in which the opponent’s lateral shape is at its weakest. This is especially the case for the back-five.

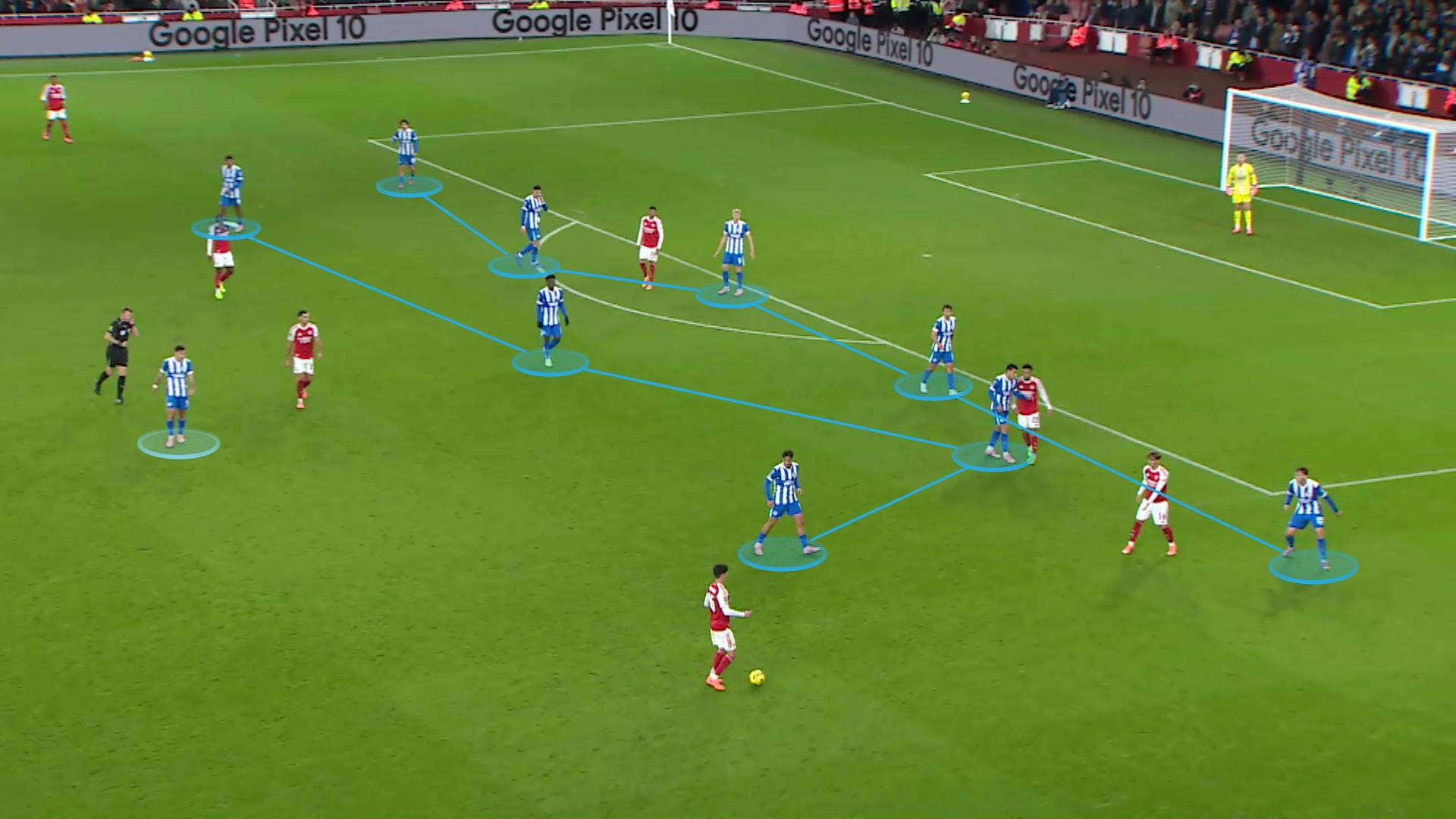

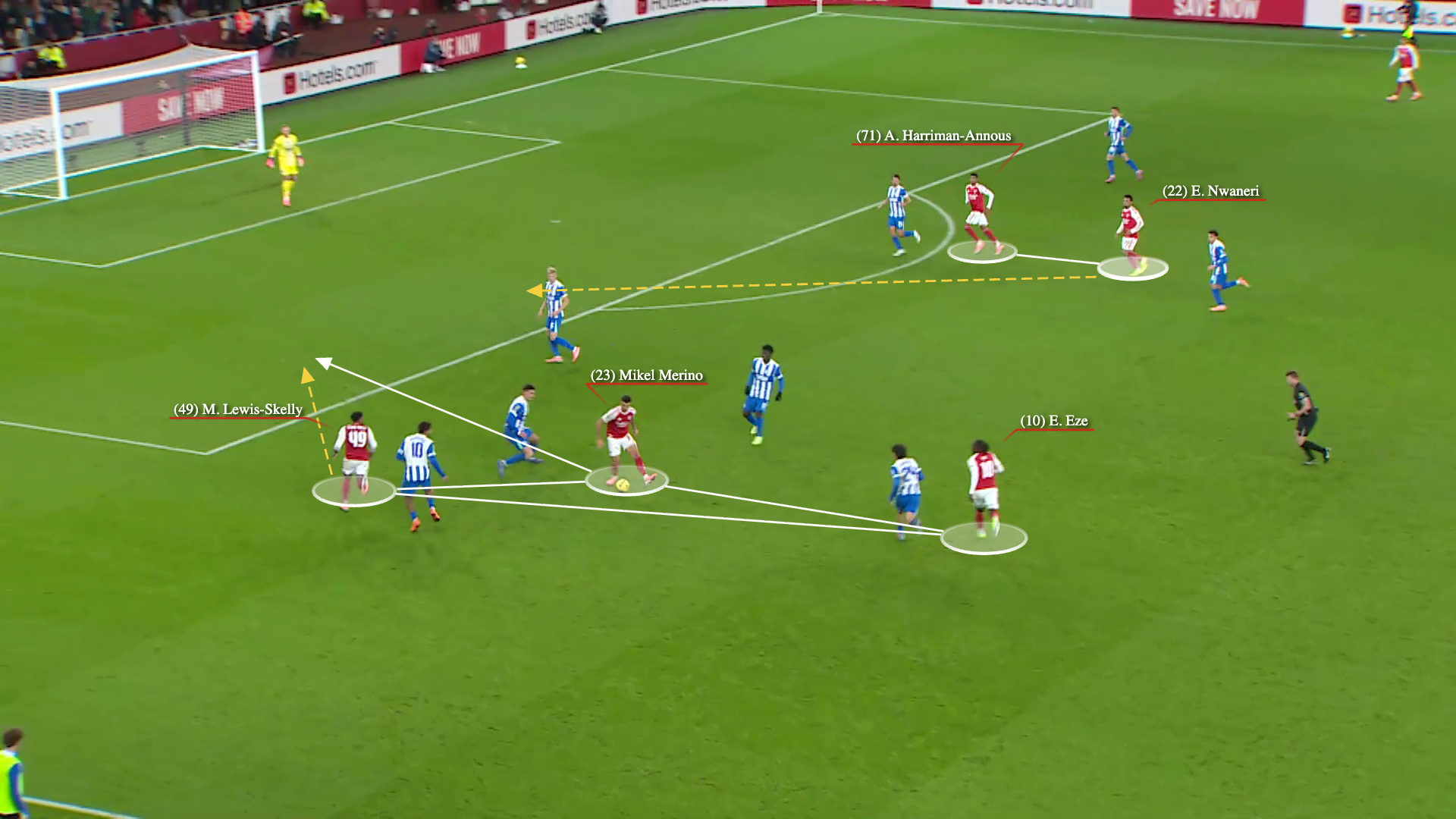

Keeping with the theme of the day, Fabian Hürzeler opted for a back-five against Arsenal in the energy drink cup. By my records (or Transfermarkt’s, rather), it was the first time this season that he had done so.

This was to be a difficult test, as Hürzeler is a bit of a giant-killer himself. It would require some pretty aggressive leans.

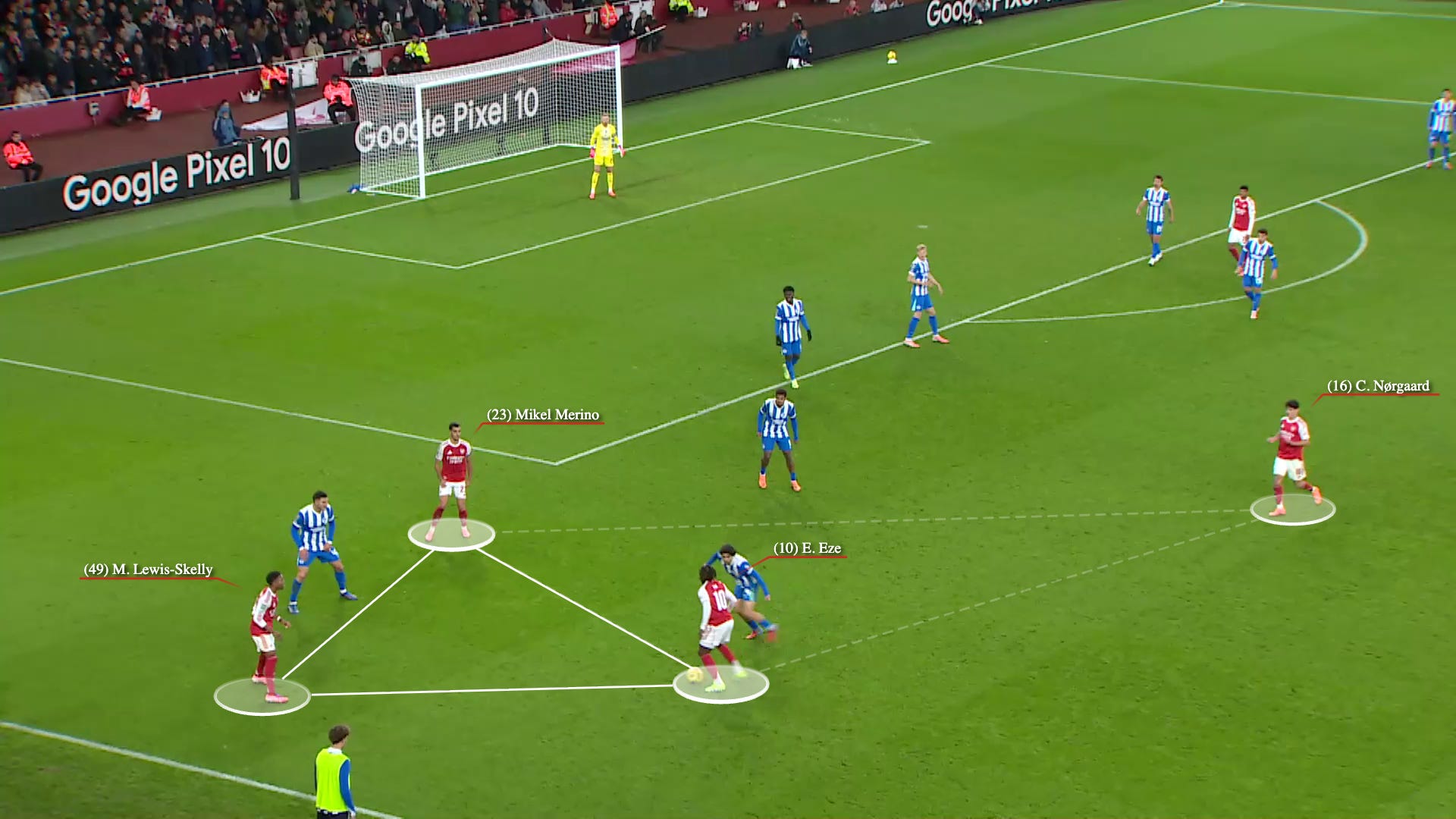

Here’s what that looked like out left, in which a little triangle has formed. It was great to see Eze out on the left-wing, and Nørgaard is joining to make it a diamond. A risky pass could have been made, but there wasn’t much doing because of the back-five.

So there’s a grounded switch of play. And you’ll see some early hints of how quickly most players go to join that side for a potential overload.

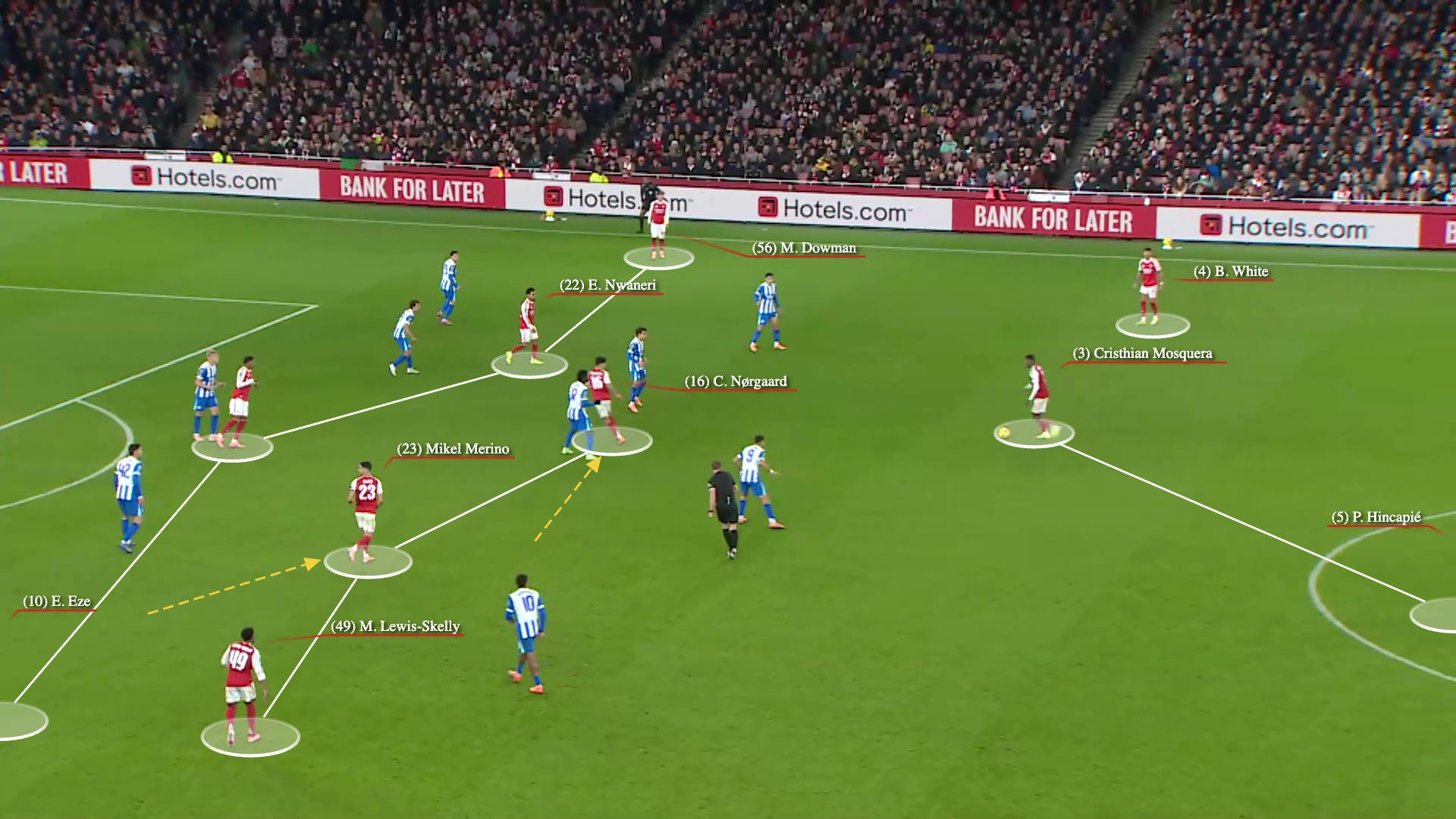

Within a few seconds, Mosquera has pushed up, Nørgaard has picked up some advanced spots like Zubimendi is prone to do, and Merino is floating over as well.

White has an awkward touch, and now we switch back to the left. The important point: the last action is performed at speed.

…and here’s where the magic happens. Eze gets off the touchline immediately, and everybody else is arriving into position, instead of standing in place.

We’ll see another calling card: Nwaneri hooking himself up to the striker (in this case Harriman-Annous) before bursting across to shoot. It’s just really hard to track players arriving behind strikers.

…and here it is, at full speed.

It wouldn’t be Nwaneri’s only time in that zone. He had seven shots on the day.

Burnley? Also a back-five. And a really solid, disciplined one. I probably don’t need to tell you this, but they allowed 16 goals in 46 matches in the Championship last year. This is the exact kind of matchup that may have tripped up Arsenal in years gone by.

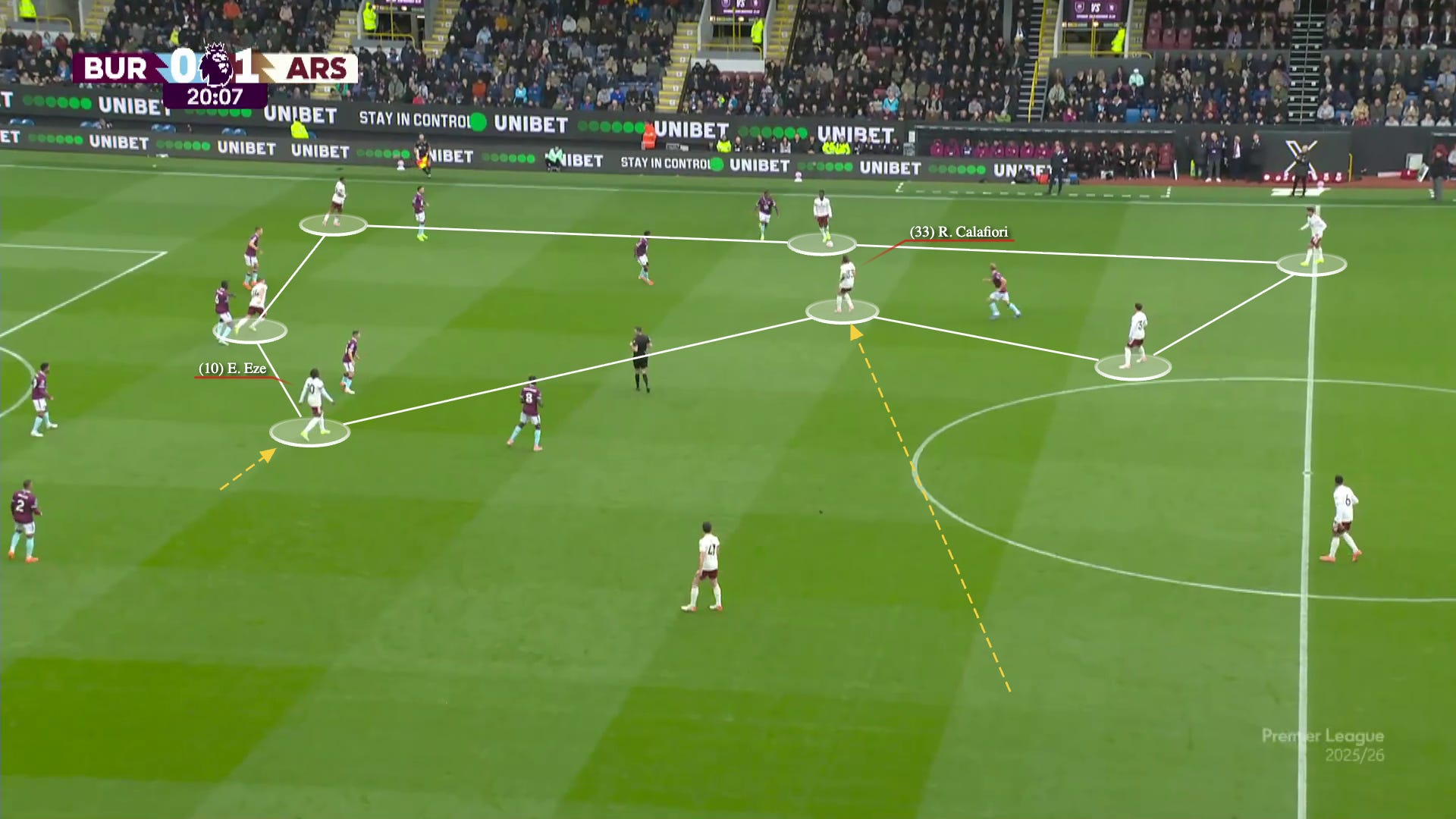

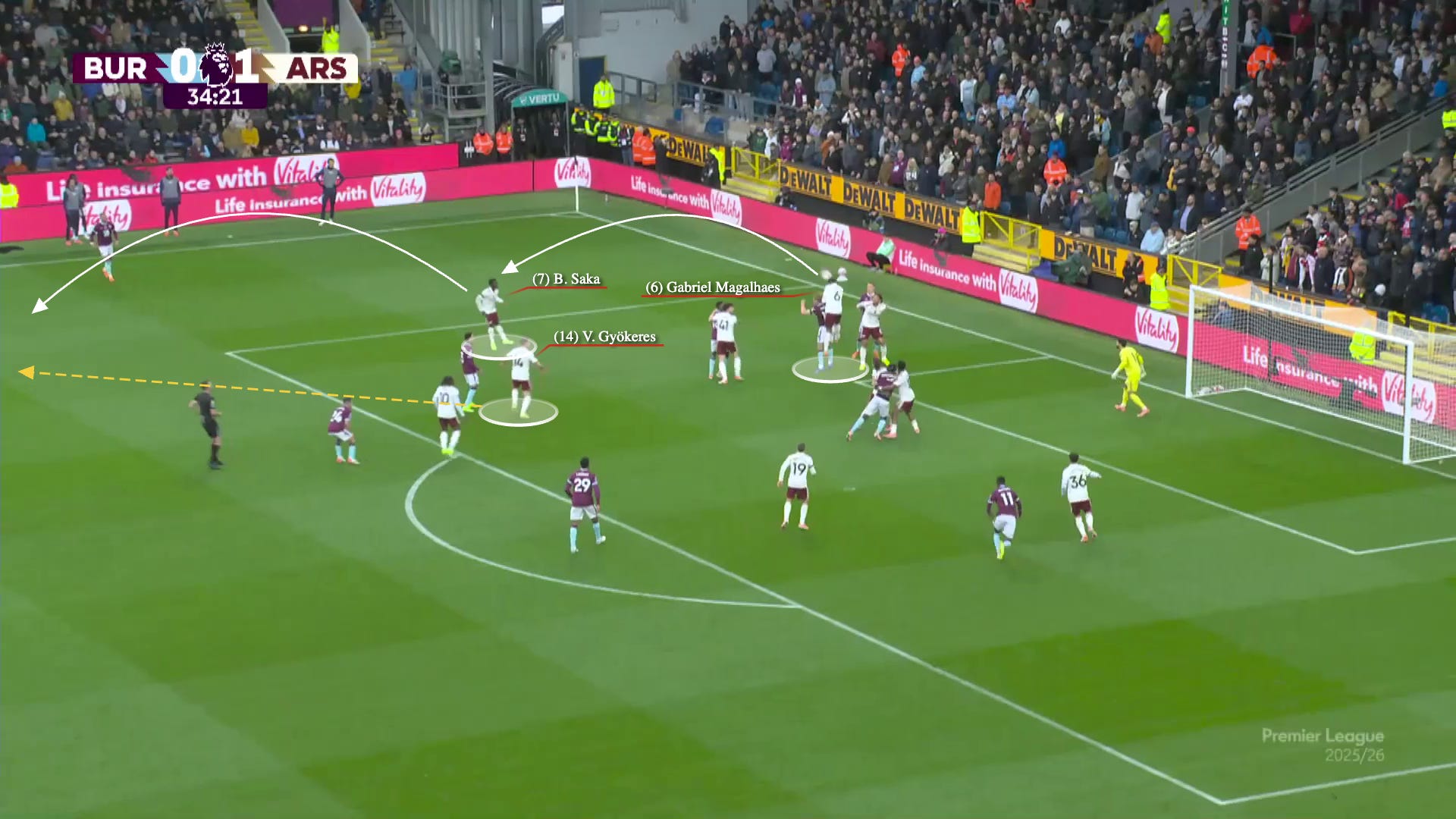

The joy was again found through aggressive ball-side leans and a see-saw aspect to play that would quickly break things open. Here’s Calafiori doing Calafiori things.

Then there was a switch of play, and the important thing to reiterate here is that all the other players are arriving at their spots to support the winger, instead of just waiting there.

Trossard was asked about Calafiori and sang his praises.

“I have a good relationship with him at the moment, so I know what he can do and where he can pop up in what position. Sometimes I can play a ball blind to him and I know he will be there.”

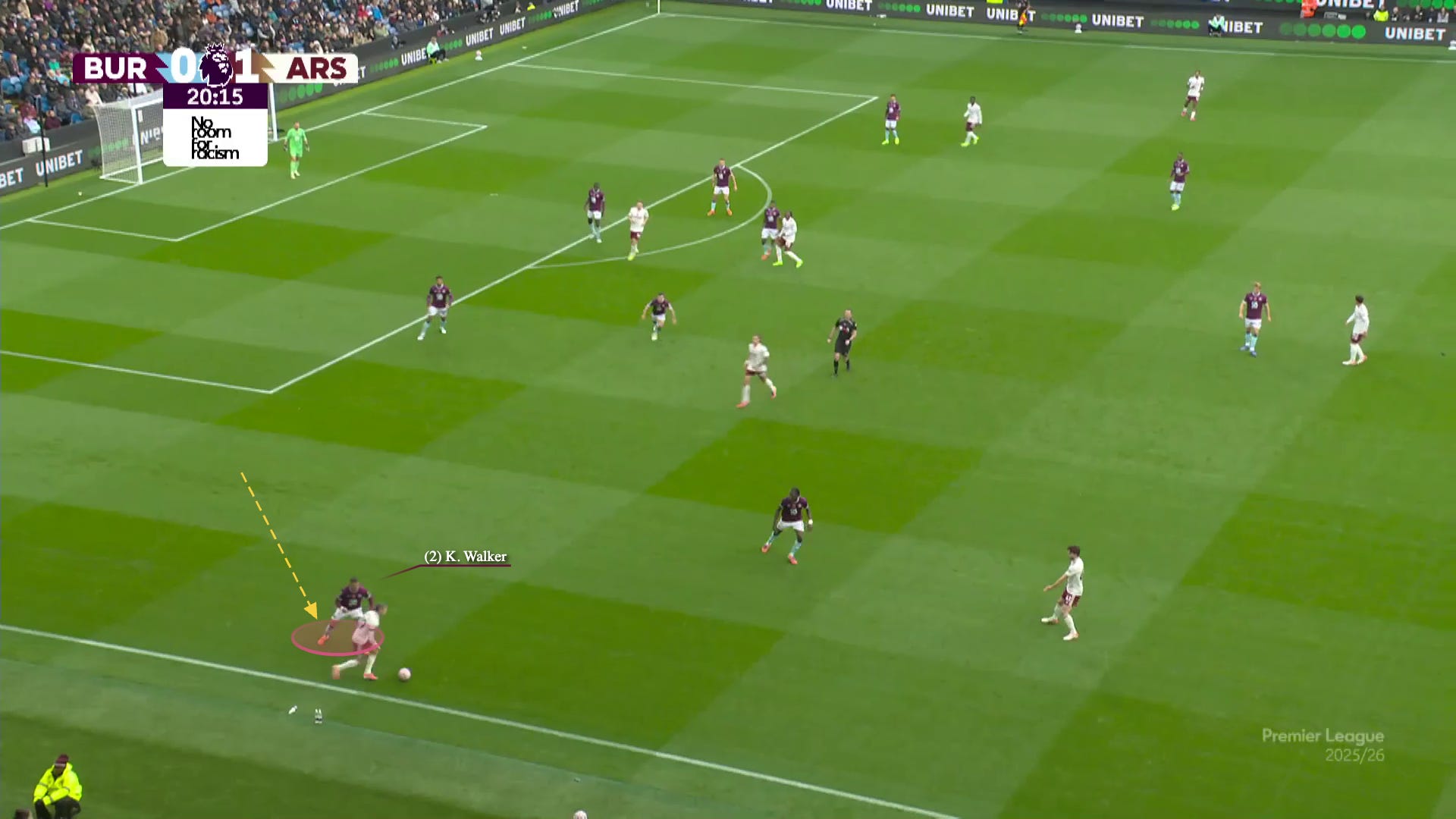

One thing we can call attention to is just how much work this puts on the opposing full-back. Here’s Walker closing down on Trossard, getting close in a zone we’ll cover more later. At the same time, Eze is leaning back this way (again on the same vertical line), and Calafiori is galloping to join the fun.

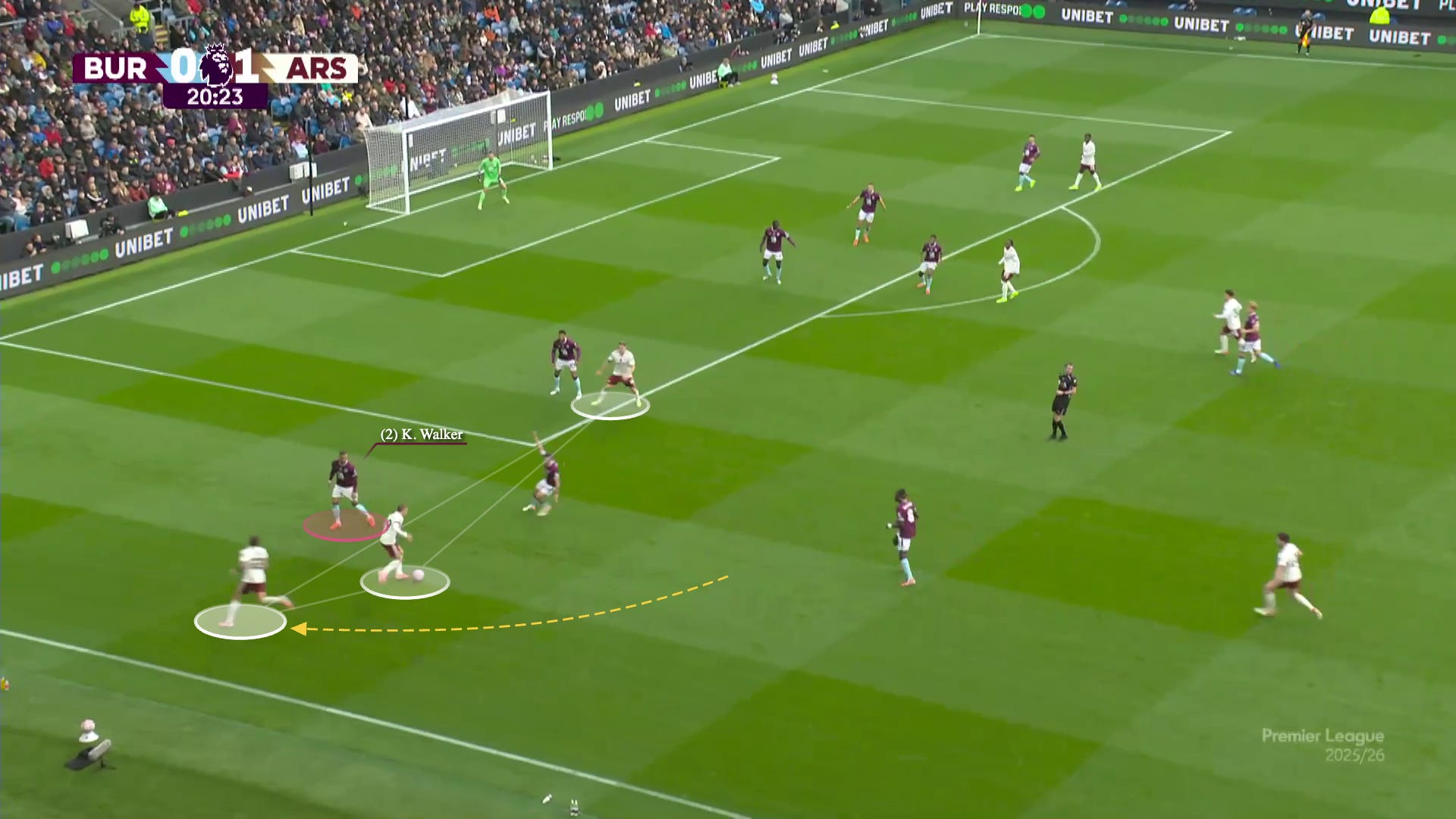

Poor Walker had too much to keep track of, and Gyökeres has joined the triangle. Walker uses his speed to catch up.

But once he’s set, Calafiori overlaps, which forces communication amongst the defenders and triggers Walker to track another run.

Walker is now doing pre-match rondo defending…

…before having to follow Calafiori all the way by the six-yard box. Trossard blasts it in, and Walker has to close out on a good shot opportunity.

…and finally:

👉 Have the widest player drop, then attack the space behind

Dragging the opponent’s full-back forward creates an opening to run in behind. This works best when paired with midfielders who can pick their passes correctly.

The first two rules of breaking mid-blocks are to a) score via set pieces and b) score when the mid-block isn’t mid-blocking. It’s just hard to score against them in even game-states when they’re lined up how they trained. But it can be done, so I pulled a long list of goals scored against the best mid-blocks in even game-states. This kind of play was a recurring theme:

In this example from Villa, the opposing full-back is forced into a difficult decision. Watkins pins the opposing RCB, and a lot of communication is required to track the diagonal run in behind.

Year-over-year changes can be overstated, but I do think that Arsenal have made a concerted effort to avoid slower, 1v2 winger moments out wide (where Trossard and Martinelli are not at their best) with some better mechanisms. Trossard has an interesting passing bag, and when he has a pass, he really has a pass. This first-timer is one of those balls he can seemingly hit with his eyes closed.

…and because it’s not closer to the corner flag, it pulls the full-back up, and preserves the space for channel runners to get in behind without getting doubled. The full-back (or wide CB) then has to sprint to rejoin the play.

It’s odd when a fanbase’s ambition in a transfer window is outstripped by a club’s, as it’s usually the other way around. Many of us would have been comfortable moving Trossard on if it meant a player like Eze joining; few thought we’d get a striker, and a winger like Madueke, and Eze, and keep Trossard. (I don’t want to call out any specific analysts, but one idiot’s name rhymes with Chili Sharpener.) In any case, Trossard has been one of the unsung heroes of the season, and managed to log 7 G+A in the equivalent of 8.2 games.

These quick changes of direction, these acts of pushing and pulling, have helped turn attacking mid- and low-blocks from something nervy into something more procedural. There have been tweaks in speed, tactics, and personnel, but it’s also worth tempering our credit, and remembering how our impressions are tinged by set-piece goals and the simple fact that this team doesn’t really concede football goals to opposing football teams, which is a big advantage in this sport.

I do think we’ve done a better job of avoiding situations where individual players aren’t at their best.

Have the demons been fully exorcised? I’m not sure. More await. But so far, so good.

🙋♂️ What’s changed, really?

Here’s one of my little bits of fortune cookie wisdom:

Whatever you’re looking for in a football match, you’ll find it. You can find clips of any player doing anything: walking, ducking a challenge, losing a duel, missing a chance. You have to constantly interrogate your premises and ask yourself what you’re looking for and why.

When results shift, we all have a reflex to explain them with our preferred theories. Every win becomes proof of a tactical masterstroke; every loss, evidence of a fatal flaw. But the truth is often less tidy, and perhaps less interesting, than that.

To that note, it’s worth noting what hasn’t changed dramatically:

Arsenal’s attack is averaging 1.53 non-penalty xG, compared to 1.54 last year.

Arsenal’s attack is averaging 1.8 goals, compared to 1.76 last year.

Arsenal’s shots/90 is nearly identical: 14.30 this year, 14.32 last year.

What has seemingly changed?

Arsenal are spending more time in the middle third, with 304.6 touches per 90, compared to 272.7 last year.

Advanced killer balls (like key passes) are down, but through-balls are up (and leading the league).

Arsenal’s defending has turned from great to historic. I attribute this to experience, Zubimendi’s presence, Rice’s improved role, Calafiori’s improvement, and the massively improved depth and legs that come with it.

…and, three elephants in the room:

Arsenal have scored 10 goals on set pieces so far.

Arsenal are fucking up less. I attribute a lot of this to depth and Martin Zubimendi. We dropped 21 points from winning positions last season, and 0 so far this year.

Not to trigger you, but: last year, there was a 16% chance of a game having an Arsenal red card.

The first thing I’d say is that, despite our improvements in depth, we do miss Ødegaard. Don’t let anyone tell you differently. There can be a bit of deep orchestration and tempo-setting that is lacking right now, and it’s especially apparent when Zubimendi isn’t playing.

Arteta noticed the losses against Brighton.

“It’s some very sloppy giveaways that we did give, in very dangerous areas. We didn’t apply two or three rules that we always have in second phases, for example, and we could have been punished. Kepa made a brilliant save, they made another big chance. It was more the feeling that we were struggling a bit.”

He did qualify it:

“But to be fair, I expected that, when you make 10 changes and you put players that have never played before, some of them, they haven’t played much as well this season, you have to gamble.”

Nwaneri is getting involved in all phases, and has shown his moments from deep, but is still working on a) scan timing, b) seeing the whole pitch, and c) predicting pressure when facing Premier Leaguers.

Elsewhere, there are the simpler issues of new connections being formed. There’s also the secondary one, which is that Nørgaard doesn’t replace the deep orchestration of Ødegaard or Zubimendi, and has logged a few deeper losses so far. This was one of my reservations about the signing, though you can’t argue with the price or leadership qualities.

This one was just the confusion that naturally results from these new connections.

A lot of these issues were bailed out because Mosquera and Hincapié share the same top quality, which is: all-out, last-ditch defending.

And it also shouldn’t be overstated. Despite some hitchiness in deep possession (Gabriel has contributed at times, too), Arsenal are still outliers here.

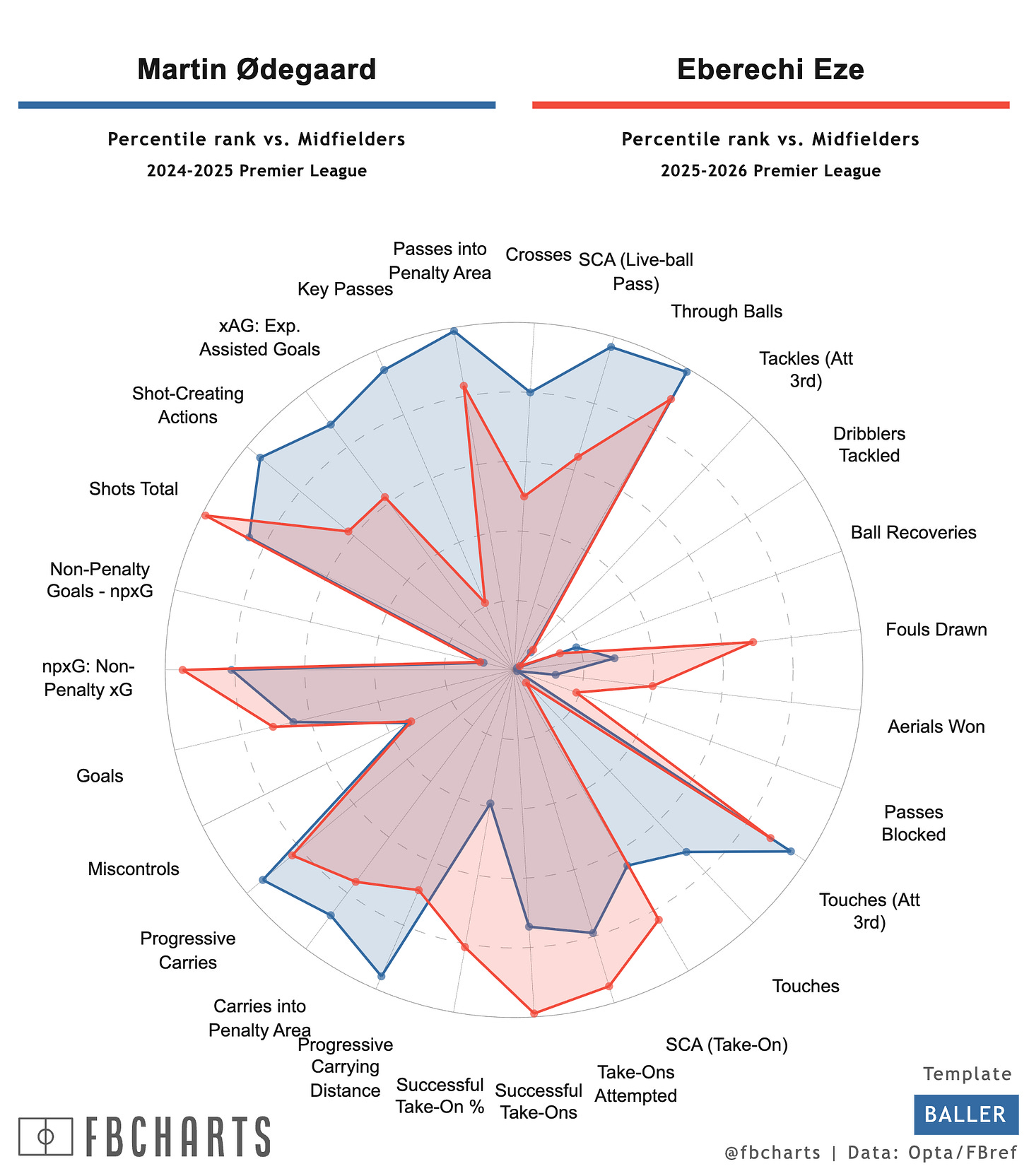

And some of it is the stylistic difference between Ødegaard and Eze.

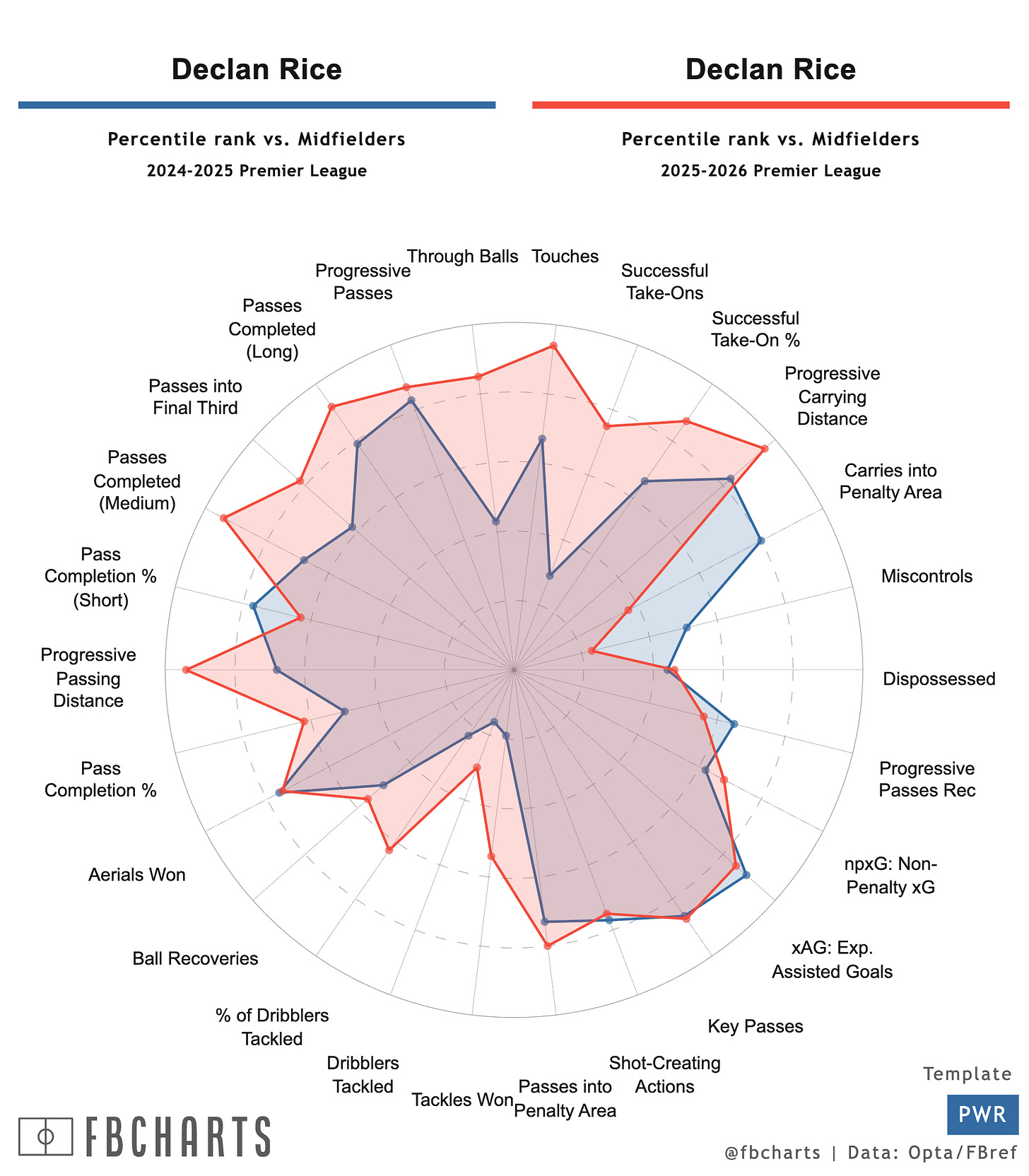

Some differences are pretty stark. Comparing Ødegaard’s (fairly disappointing) last year to Eze this year, while keeping sample size and positioning things in mind:

Key passes: Ødegaard 2.44 / Eze 0.59

Passes into the pen: Ødegaard 3.33 / Eze 1.03

Passes into the final third: Ødegaard 5.12 / Eze 1.91

Live-ball shot creation: Ødegaard 3.91 / Eze 1.91

Above all, Ødegaard has a superhuman ability to notice things aren’t going at the right speed, skip down into the pivot, take two touches, and break the opponent press at will with a simple line-breaker, without ever losing it. It’s something he does better than virtually any 10-ish player around, and is something we tangibly missed against Crystal Palace. According to Gradient, Ødegaard still leads the league in passes breaking multiple lines (2.34 per 90).

But it’s more nuanced. For one, Ødegaard can also contribute to more cosmetic progression, in which he makes the by-the-books move that allows the team to progress to the final third, but without imposing enough speed or advantage. For another, the hope is that with Saliba, Calafiori, Zubimendi, and Rice, the requirement for that deep orchestration is lower, so that the right midfield spot can really focus on doing as much damage as possible.

We’ve still seen beautiful setups like this.

Which resulted in this. Eze isn’t quite Ødegaard’s level as a build-up “fixer,” though he has some interesting potential there, but he can absolutely drop and make great whips from here. I don’t have to remind you about the ball to Martinelli against Man City.

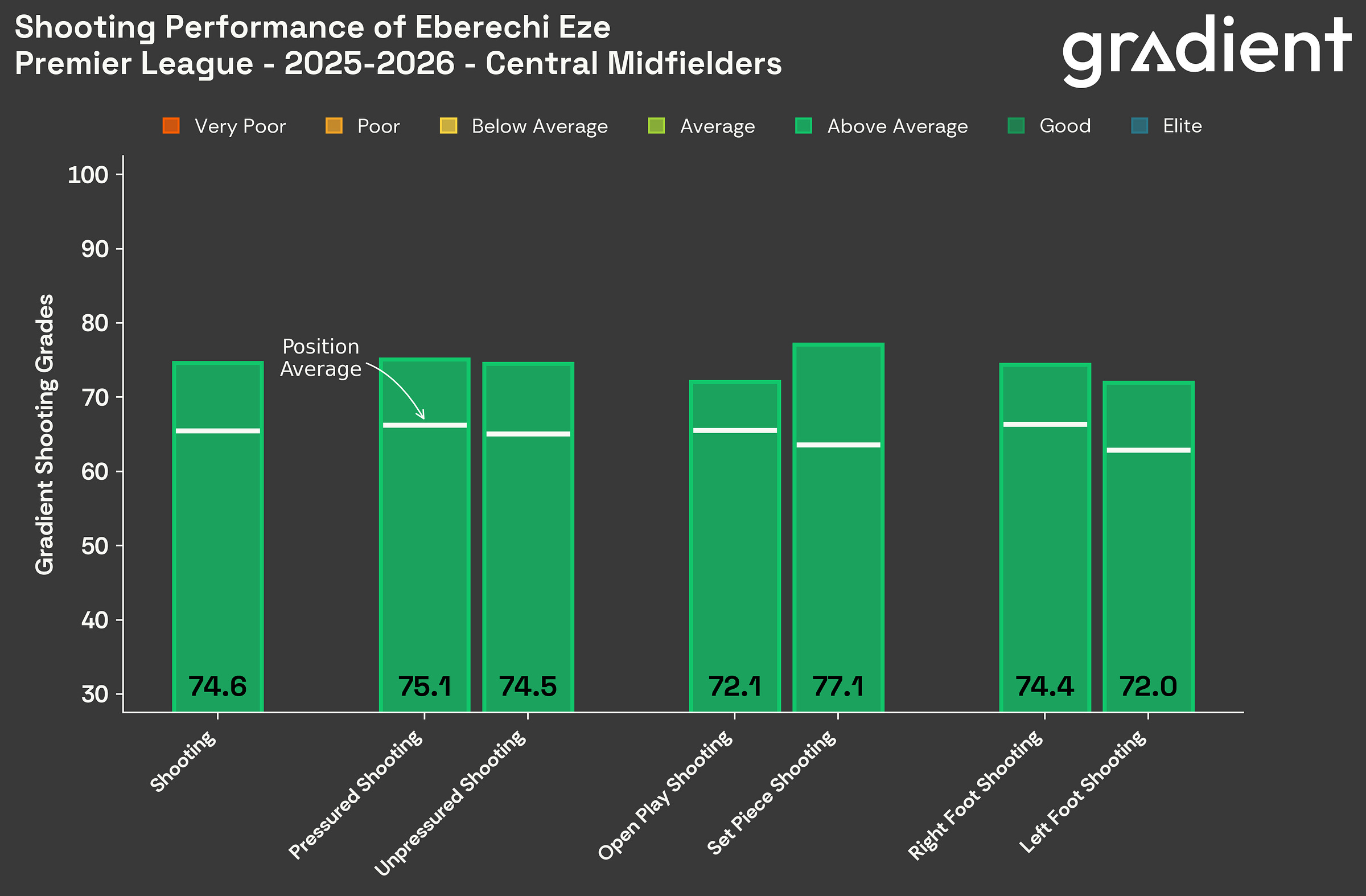

Then, we have Eze’s bigger advantages. The first comes from his perpetual green light, which has had a big impact so far.

You’ll see a moment like this, in which he drives directly at the line and rips a shot that bounces off the crossbar, and Rice almost knocks it in on the rebound.

And that is really the big difference. Not only can he hit that off his right (of course), but he could have played Saka in as well … but he didn’t. He took the shot. Arsenal have been desperate for this kind of player.

That’s how you create your own luck. This first-time smash bounced right to where it always seems to: the penalty spot. Rice manages to dispatch this one.

We saw earlier how his karate kick on arrival helped Gyökeres get his first Champions League goal for Arsenal.

It was the same urgent, jumping form that netted him his goal against his old teammates.

Again, this has wider implications:

Eze leads Arsenal regulars in shots (2.54/90).

Arsenal lead the league in shots that lead to another shot (26), with five players in the top-20. (Set pieces play a role in this, as well.)

Critically, Arsenal now lead the league in “open play power shots” (26), 12 more than the second highest (Gradient). Arsenal have the highest percentage of “power shots” in the league (19%). Eze leads this league, with 7.

After Fulham, Arteta had some interesting quotes:

He’s more used to probably attacking open spaces and breaks and facing and carrying the ball with the space in front of him, but he’s so good and comfortable doing that. I think he had his moments today, he put Viktor I think one or twice through in really good spaces and maybe if that would have finished in a goal it would have looked a little bit different. But I’m very happy with what he’s doing and we can use him in different positions, and today we used him on that one and we carry on trying to improve.

Against Burnley, he showed his quality.

He had an interesting, more left-leaning passmap in that one.

There is another edge: he is a highly impactful player in transition, with or without the ball.

My pal Jake has a great thread up about how teams are doing long throws just to do long throws, holding up this Burnley moment as an example. They did one, and Gabriel got on the end of it; then they did another, and Gabriel got on the end of it again. The second one sent Arsenal off on a transition.

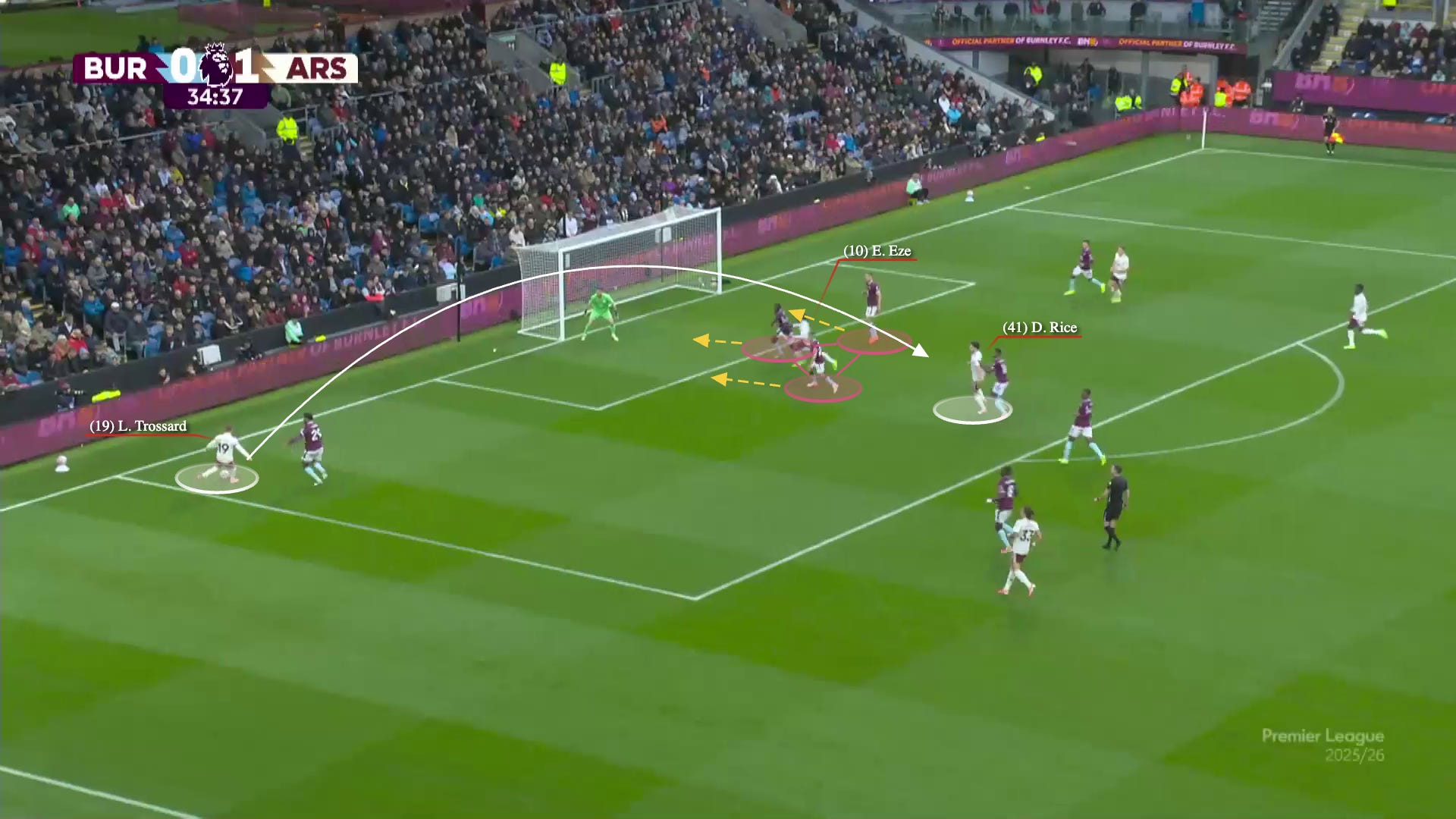

From there, it’s easy to see the contributions of those who touched the ball, particularly Gyökeres, who beautifully backspinned a ball across the line, giving Trossard a moment to collect and deliver the assist.

From there, Trossard used his left to hit it to the (say it with me, again) penalty spot, where Rice arrived to head it in. But my point in bringing this all up is to look at Eze, the unsung hero of the play: directly after the win, he was sprinting high in the striker spot, pushing the line back and attracting attention. Once in the box, he bulldozed three defenders down, which cleared the room for Rice to arrive and score.

According to the gospel of legendary coach Juanma Lillo:

I used to say in Manchester that the last player to arrive to the box is the first one to be able to shoot. I tell that to my strikers all the time: the closer you get to the goal, the further you are from scoring.

Rice has been living the gospel.

Eze, meanwhile, has shown his quality in spurts, and has also displayed how his impact will differ from that of Ødegaard. Ødegaard, at least for now, can better help facilitate overall play, and prepare the conditions for that final attack; Eze can seemingly create that final attack out of nothing.

If you’ve followed Eze for years, you’ll know how he can be pretty hot-and-cold. In his hot periods, he can look like one of the best players on earth. Though highly important in key moments, I don’t think we’ve seen that Eze yet. That’s reason for optimism.

But there is another niggling issue which we’ve alluded to: without Zubimendi or Ødegaard, Arsenal can lack that overpowering, deep feeling of facilitation and tempo. This was especially the case against Slavia Prague, a game in which the team started without many of its best deep playmakers: Zubimendi, Ødegaard, Eze, Lewis-Skelly, Calafiori, and White.

The solution was something that we’ve low-key seen before.

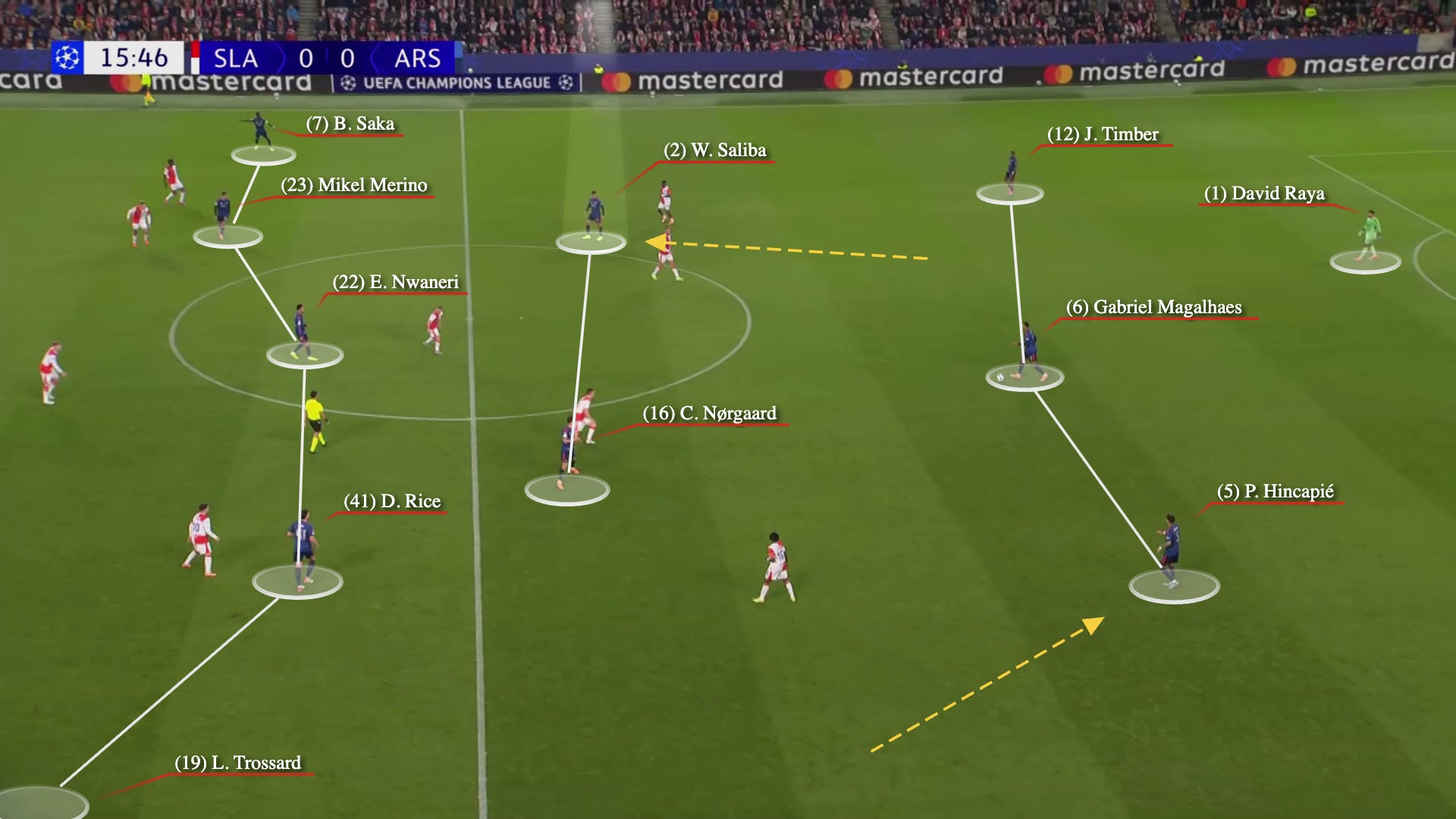

Against Newcastle last year, we saw Saliba jump into the “Stones Role” situationally, to hide behind their front presser (in this case, Isak).

Against Palace, with Timber filling in for Saliba at RCB, we saw more of it. It was clear that this was part of the game plan.

At other times, Saliba has embraced full freedom, like he did against Bournemouth: doing a Matip-style run, a 1-2, and ripping a shot after an underlap.

Arteta was asked about Saliba stepping into the midfield against Slavia Prague.

That was related about the way they press, and the way the nine makes the press and the way where we could find certain advantages and time, because if not, everything is absolutely man-to-man. And it’s a really difficult game to play constantly, especially after the direct play. And we could have done better; it’s something we haven’t had time to train really. So, to have more solutions and to try things, and to especially put players in their qualities with a bit more time on the ball. It’s something that I wanted to try.

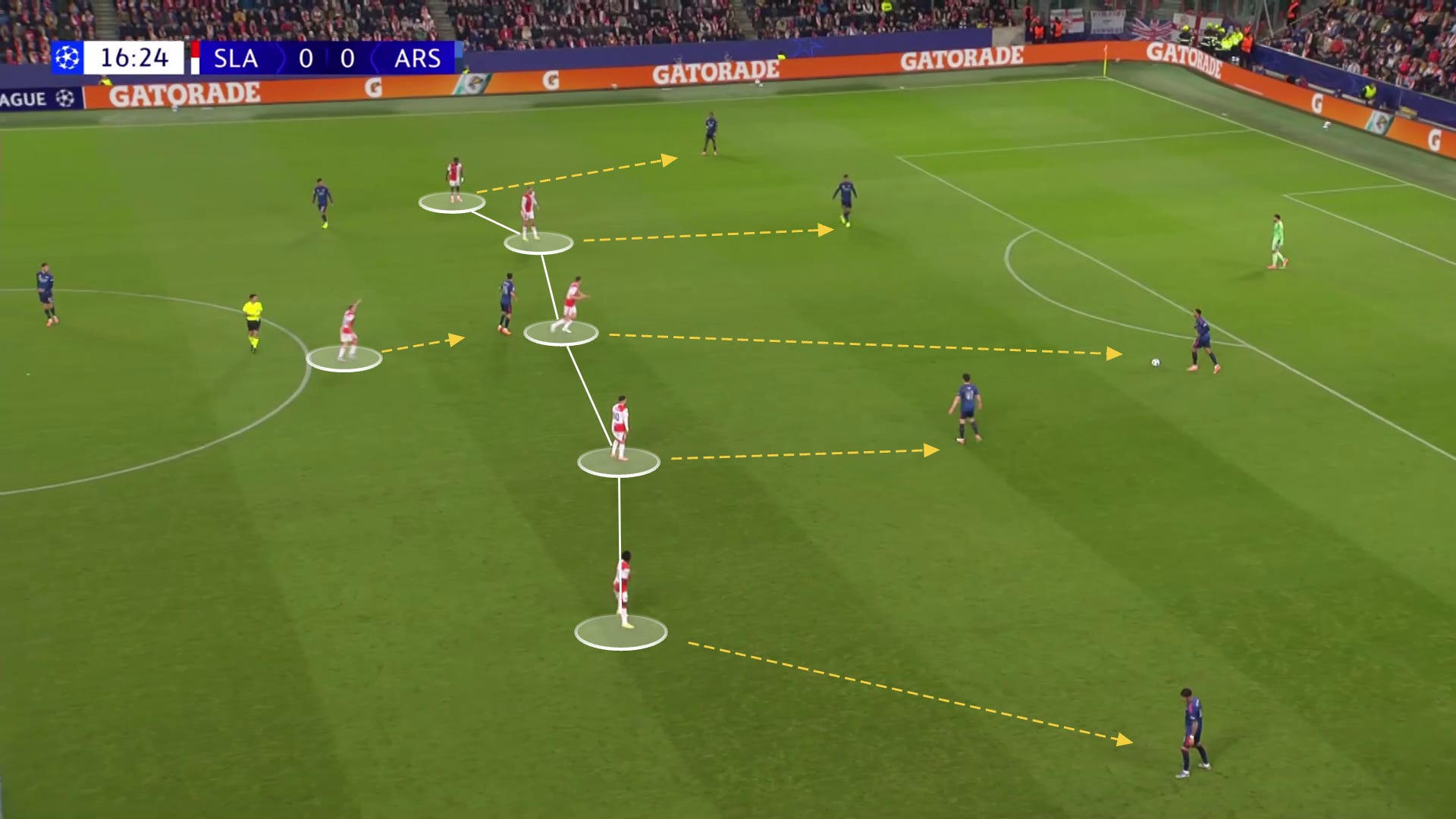

When Arteta says that if you don’t take advantages, then “everything is absolutely man-to-man,” this is what he means. You can see how simplistic the press looks when you sketch it out like this:

The arithmetic there is fairly simple: if somebody steps up to jump on Raya, then there’s no point in having another player back there, and the +1 should exist in the line behind.

But I reckon there’s another reason that Arteta was interested in trying this out, that he is more hesitant to mention. With no Zubimendi, Ødegaard, Calafiori, or Lewis-Skelly out there, Saliba might literally be the most threatening back-to-goal player on the pitch. The others have their limitations.

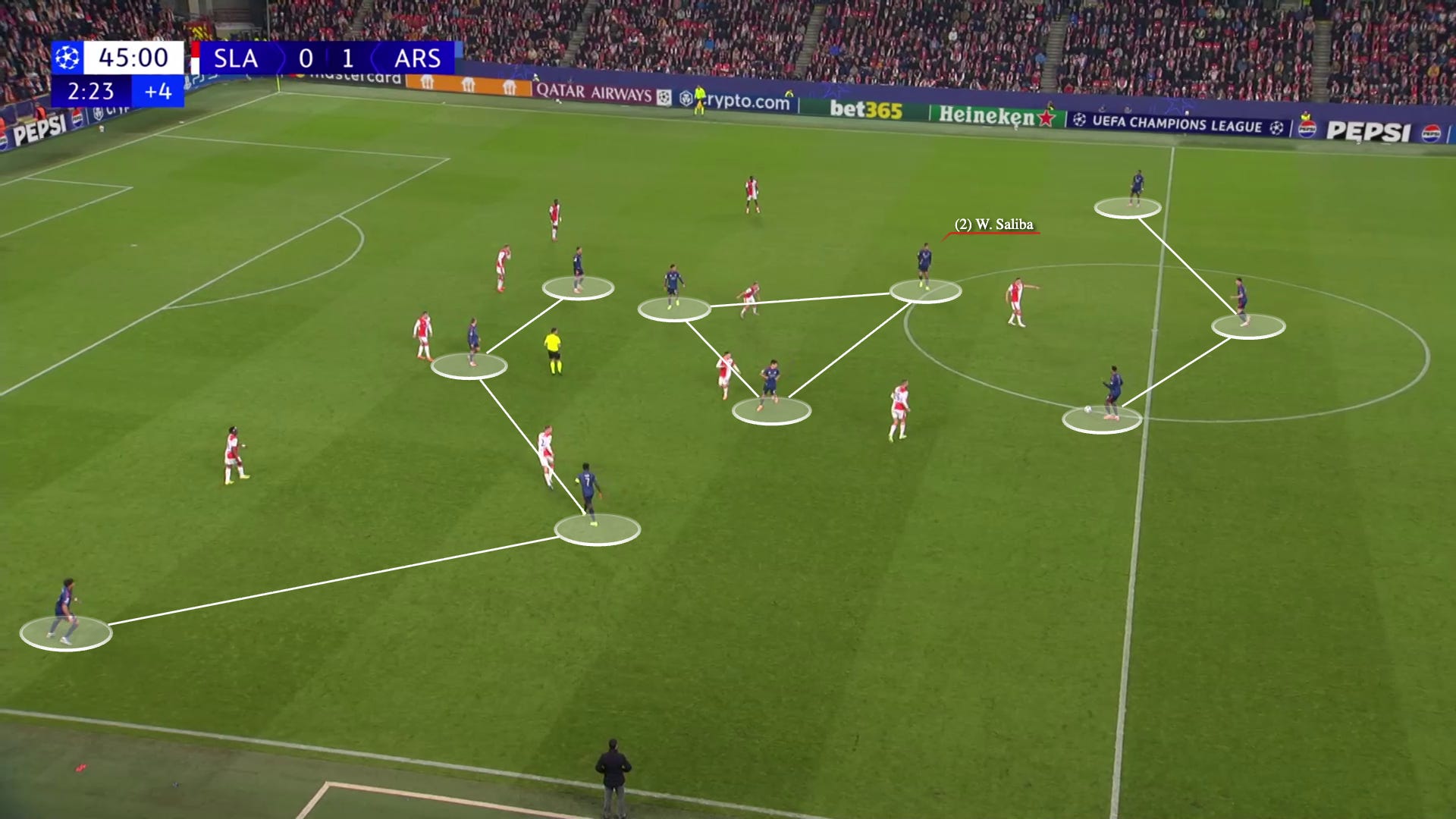

Saliba is one of the best players on the team in those 360° scan-and-turn situations. Been playing freer with Gabriel improving at holding the fort in the middle. It was even looking Inter-ish at times (Jorginho low like Barella, Saliba ahead of the ball in the midfield).

He is, simply, very good at this job. Nørgaard is pragmatic but isn’t the most threatening from these positions, Timber hasn’t fully blossomed within the midfield pivot (he’s found a home in wider spots), and Hincapié projects as more of an outside-the-block passer; but Saliba looks good whenever he does this.

You’ll see that frontline stepping forward, Saliba dissolving behind, and Timber dropping to keep the back-three intact. Part of this is also about Gabriel improving at CCB, and Hincapié doing his best work out here.

In truth, we saw moments like this…

…and this:

…and Gabriel was able to thread a nice one through the spot that Saliba was manipulating.

But other than that, it was a little awkward and herky-jerky. To my eyes, it didn’t foreshadow a massive tactical shift. It looked like Arteta trying to find answers without some of his best deep passers on the pitch. It’s a worthwhile experiment.

📝 Scattered notes on Rice, Gyökeres, more

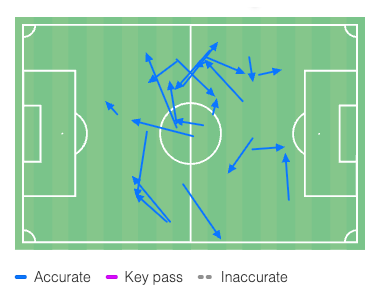

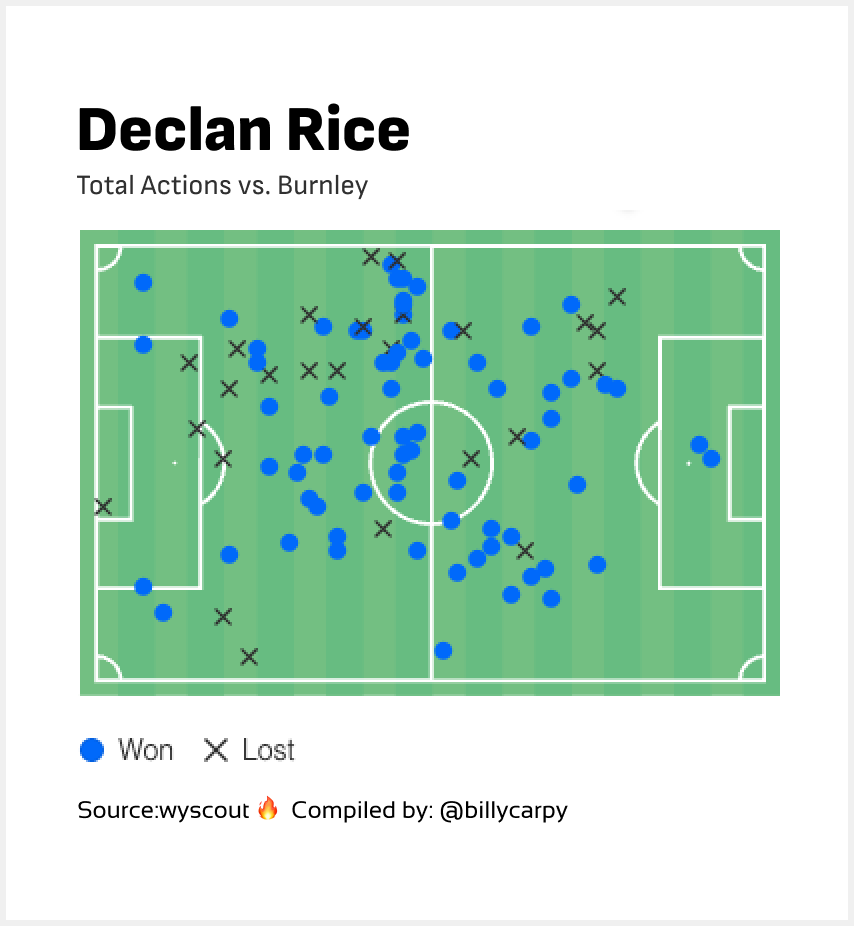

It’s hard to talk about Rice without it just turning into boring fan fiction. Against Burnley, he logged 21 defensive contributions, 5 tackles, 3 interceptions, and 9 recoveries; it was all-world stuff that defies superlatives. Here’s what his total action map looked like:

His updated suite of responsibilities has suited him well. He is a player who can often play himself into his best shape and peak in the second half. He seems to be intent on speeding up that timeline this year.

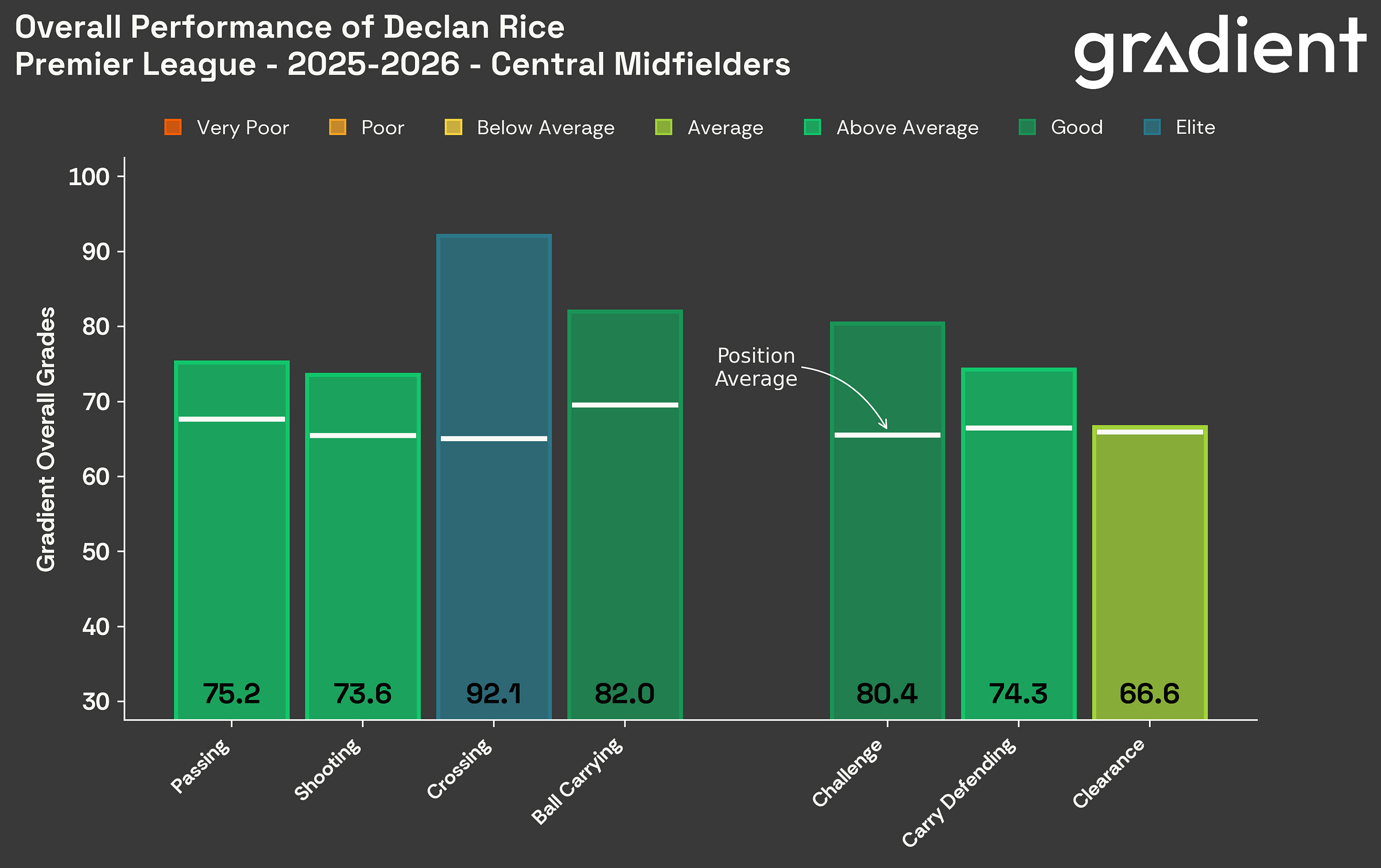

When benchmarking through Gradient, he is succeeding across the board.

What’s been nice is seeing some of his open-play crossing tick up.

But for all his curling corners and free-kicks, I find myself most gobsmacked about his talents when he’s going in for a loose ball: balanced, leggy, agile, fearless, and freakishly quick.

I’ll say it: I think he was a good signing.

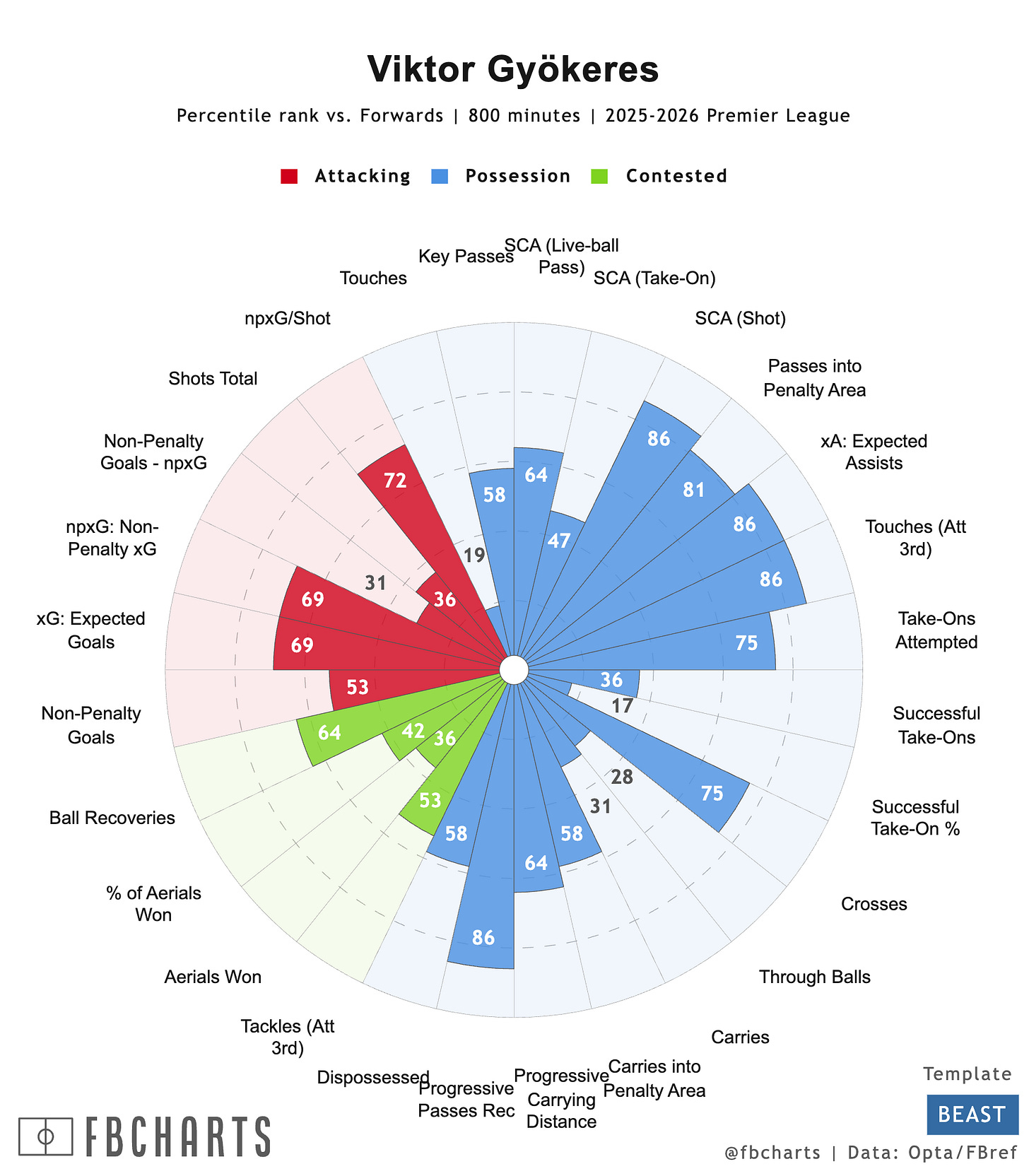

Meanwhile, here’s Gyökeres to date:

As I said last time, I think he’s been at the 50th percentile of possible outcomes: about what I’d expect. He’s able to challenge and compete and be relentless and successful, but he can face challenges with reliably forcing separation so he can get his shot off against Premier League defenders.

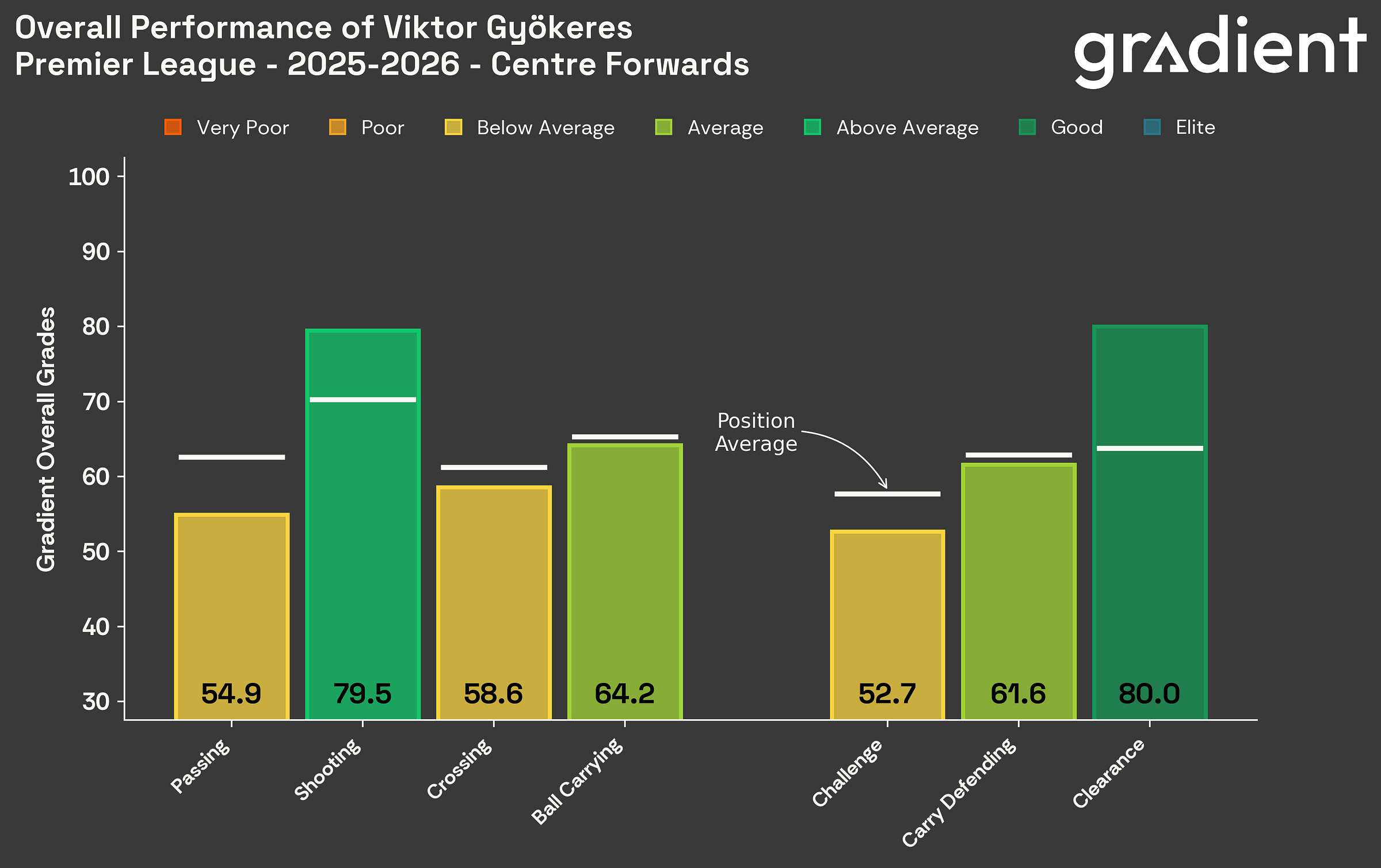

Likewise, here are his Gradient grades:

I will say a couple of things. His defending has been a significant leap over what I expected; not only is he going all-out, he’s starting to get his angles in a really good spot. He is officially, fully Arsenal-brained (tissue injury and all):

The other thing is that his touches were genuinely amazing against Burnley.

To date, my worry about his bouncy touches has so far shown up in his Premier League footage. What you’d typically conclude is that, facing Burnley, he just had more success against weaker competition. But if you watch his actions with clear eyes, you may say: he got some rest, and the touches were pristine. This is the kind of thing that fatigue, or lack of fitness, can have a real influence on.

He’s out for a bit, and I eagerly await the returns of Jesus and Havertz, but I agree with Arteta: this was clearly his best performance in an Arsenal shirt.

Here’s a little preview of what your left side could look like at some point in the season.

…and finally:

I will speak about Dowman at a later date. Thank you for your understanding.

For as good as the structure is, I think we’ve also seen a lot of confirmation that a big part of the reason Arsenal don’t allow football goals is because they have the best CB pairing in the game. Gabriel’s communication and verve has been otherworldly this season.

I’m still getting my head around the Saka performances this year. My initial impulse is to say he’s been great, and it’s fine if his touches are lower and he’s more off-ball, darting in behind: my inclination is that he’s just missed some shots. But his shot-taking numbers are huge in the Champions League, and down domestically, so it requires a little further evaluation.

I think there was more inexactness and minor build-up issues against Palace, Brighton, and Slavia Prague than may have met the eye, given the respective scorelines. I didn’t ultimately love the Palace setup, with Calafiori as a deep LCB and Rice playing higher.

I feel so much better with Kepa between the sticks than I may have otherwise. David Raya has the highest sweeping actions in the league by a margin, and Kepa has done a great job of a) saving shots and b) keeping team identity in place.

In a vacuum, Ryan Gravenberch is probably Liverpool’s fifth-best player or so. But they are so dependent on his abilities, that he may be their single most pivotal, and their most costly absentee (other than VVD). I sometimes wonder if Zubimendi is in the same boat, though it’s probably Rice or Saliba.

Style of play impacts everything. That means:

More high/wide play = more pinning of opponent wings + transitions

More central dribbles/combos = more end-to-end play

More end-to-end play = more dead sprints

More dead sprints = more injury risk

More injury risk = more depth required

I still have some stubborn faith in Jesus (the football player). If he loses a step, it’ll impact his ability to win wide, but he has it in him to be a ghosting, combining, more typical box striker, as we saw before the injury. He is one smart motherfucker.

My mild take is that Arsenal’s fans are a touch too calma about depth. Great players are great players and they’re hard to replace for a reason. Being able to cover them 90% is excellent, but still not 100%.

The Hincapié partnership with Mosquera was very good, and it will get better. I may have understated Hincapie’s ability to get minutes at LCB. But I still feel his best position will be at LB with the Rice/Zubi pivot.

At the beginning of the year, I wrote this:

Maybe we aren’t blind, but in our more anxious moments, we’re too close to the social media feeds, too close to see the full picture, our perspectives tilted. Last year, after all, amidst the injury calamities and the misfortune and the reds, the result was a second-place finish in the table and a Champions League semi-final. The most strident of doomsdayers cannot coherently argue against Arsenal’s place as one of the best teams in the world.

If I have one unrealistic wish for the season ahead, it is to cast off some of the tightness and pressures of the last few years, to keep them in the past, to keep them external, where they will assuredly be in full force, and to survey this restocked squad on its own terms, with new eyes, hopefully rediscovering the simpler hopes and joys that brought us into the sport in the first place.

For around two decades, I’ve been keeping a single big document of every interesting thing I read. It used to be in Evernote before Evernote became horrific, and now it’s just a big Apple Note. If you’re wondering where all my goofy quotes come from, this is your answer.

As I was looking for quotes that transmit a certain unbotheredness about external pressure, I found this one, from Tarkovsky:

“Some sort of pressure must exist; the artist exists because the world is not perfect. Art would be useless if the world were perfect, as man wouldn’t look for harmony but would simply live in it. Art is born out of an ill-designed world.”

But, ahead of Sunderland, I also found this:

“Baby boy, you only funky as your last cut

Focus on the past, your ass’ll be a has-what”

— Andre 3000

I hope this e-mail finds you well.

Billy is simply the best Arsenal writer around, and arguably the best football writer.

I do think we’ve both had an incredible start to the year but it does feel there is another level to go in terms of attack. We aren’t going to concede zero goals every match (well… probably not) so when our defense drops to 99th percentile from 100th, I think our attack will pick up the slack.

Writing this before the Sunderland match - just get through it and take three points, then get the attacking reinforcements for the north London derby.

Zubimendi's passing grade by Gradient is low (68.5) compared with other good DMs like Caicedo (88) or Elliot Anderson (92). Considering his better progressive pass and key pass stats than Caicedo, it seems his playmaking style and the team's tactic gave him more chances of easy pass?