Don't look back

A tour through some key storylines for the season ahead, including Zubimendi's impact on the midfield, Gabriel Heinze’s influence in attack, summer business, and Arteta’s plan to "change the puzzle"

“You’re young and the world is yours. I’m old. I don’t want to hear you talk anymore. I want to hear others talking about you … Don’t come back. Don’t think about us. Don’t look back. Don’t write. Don’t give in to nostalgia. Forget us all. If you do and you come back, don't come see me. I won’t let you in my house. Understand?”

— Alfredo, Cinema Paradiso

The season hasn’t yet kicked off, and you can already feel it. It’s mostly a buzz. Depending on your disposition, maybe there’s the other thing, too, the restless edge that comes when possibility and precarity share an address. It’s the football version of foreboding joy, the airport-book idea that just when things look bright, the mind starts also rehearsing disaster.

Arsenal have been busy, thanks in no small part to the arrival of Andrea Berta. Preseason has taken the expanded squad from Asia back to the Emirates, testing line-ups and combinations. We’ve all been sheepishly trying to figure out what is signal and what is noise. Did our eyes deceive us, or did a fucking 15-year-old spin up Joelinton?

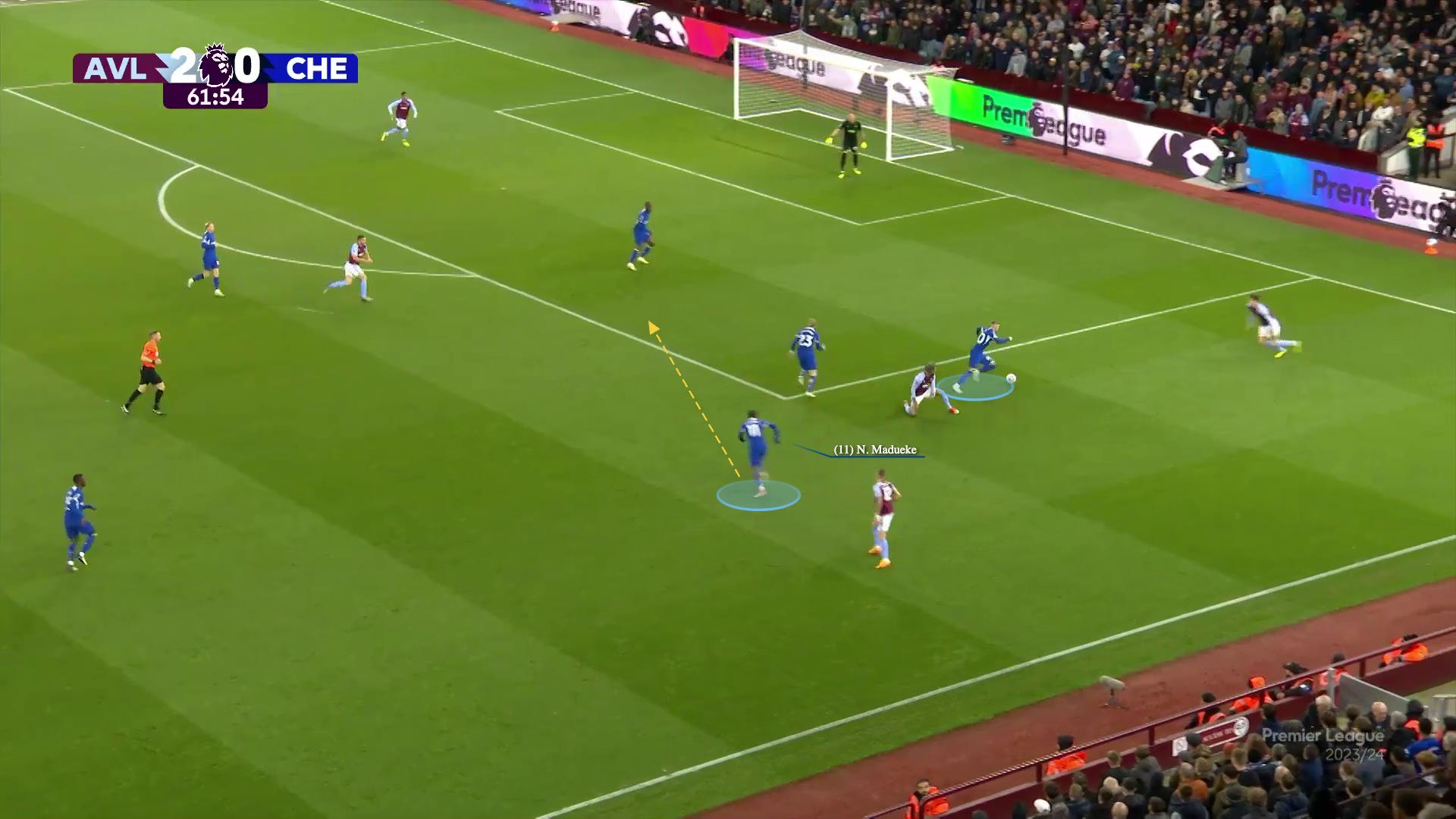

The recruitment has been efficient, voluminous, and varied. There have been ultra-pragmatic moves like Kepa and Christian Nørgaard, the surprising acquisition of Noni Madueke, and the pure fan-thrill of Viktor Gyökeres and his homemade mask. And at the crux of it all is Martín Zubimendi: a signing who already feels so brilliant and obvious that even the most cynical corners of the fanbase seem to view it without complication.

Arteta has framed these moves as “changing the puzzle.”

“We’re going to manage that in the best possible way to maintain everybody with the right cohesion, hunger, and the fact that at any moment we can change the puzzle and make it very difficult for the opposition.”

Still, none of it quiets the little voice reminding us that “almost” has been the story for three years. The anticipation is real, but it carries a tightness in the chest, a wariness born of knowing that a title challenge can unravel.

Where do we stand? A significantly deeper, more versatile squad. A manager convinced he can shuffle the pieces to meet any challenge. A fanbase ready to believe again, but braced for all eventualities, especially considering the lavish spending of Liverpool and Manchester City. And two more weeks for the squad to shift again.

Which brings us to the earlier part of Alfredo’s monologue in Cinema Paradiso.

“Living here day by day, you think it’s the centre of the world. You believe nothing will ever change. Then you leave: a year, two years. When you come back, everything’s changed. The thread’s broken. What you came to find isn’t there. What was yours is gone. You have to go away for a long time... many years... before you can come back and find your people. The land where you were born. But now, no. It’s not possible. Right now you're blinder than I am.”

Maybe we aren’t blind, but in our more anxious moments, we’re too close to the social media feeds, too close to see the full picture, our perspectives tilted. Last year, after all, amidst the injury calamities and the misfortune and the reds, the result was a second-place finish in the table and a Champions League semi-final. The most strident of doomsdayers cannot coherently argue against Arsenal’s place as one of the best teams in the world.

If I have one unrealistic wish for the season ahead, it is to cast off some of the tightness and pressures of the last few years, to keep them in the past, to keep them external, where they will assuredly be in full force, and to survey this restocked squad on its own terms, with new eyes, hopefully rediscovering the simpler hopes and joys that brought us into the sport in the first place.

It can return, but only if we let it. Don’t look back.

👉 Lessons learned

So, anyway, let’s look back.

Arteta’s puzzle-shifting is partly fashioned by the hard-won lessons of previous years. I’ve joked about my “Trauma-Informed Theory of Coaching,” the idea that managers are shaped more by their most memorable defeats than by their biggest triumphs. (There is also the companion book, the Trauma-Informed Theory of Fandom, in which every new signing is Pepe). The answer to many managerial decisions is actually a question: do you want to know how I got these scars?

That 4–1 loss to City showcased the deficiencies that were aggressively remedied with the likes of Rice, Havertz, Timber, Raya. Their ground-eating, space coverage, physicality, and Raya’s calmness between the posts, successfully vanquished the ghosts in matchups like that. Other issues remain.

This summer, the wounds from last year seem to have been diagnosed, as well. The primary aims of the window? Finishing, transitional power, and depth.

Is that a correct diagnosis? Let us see.

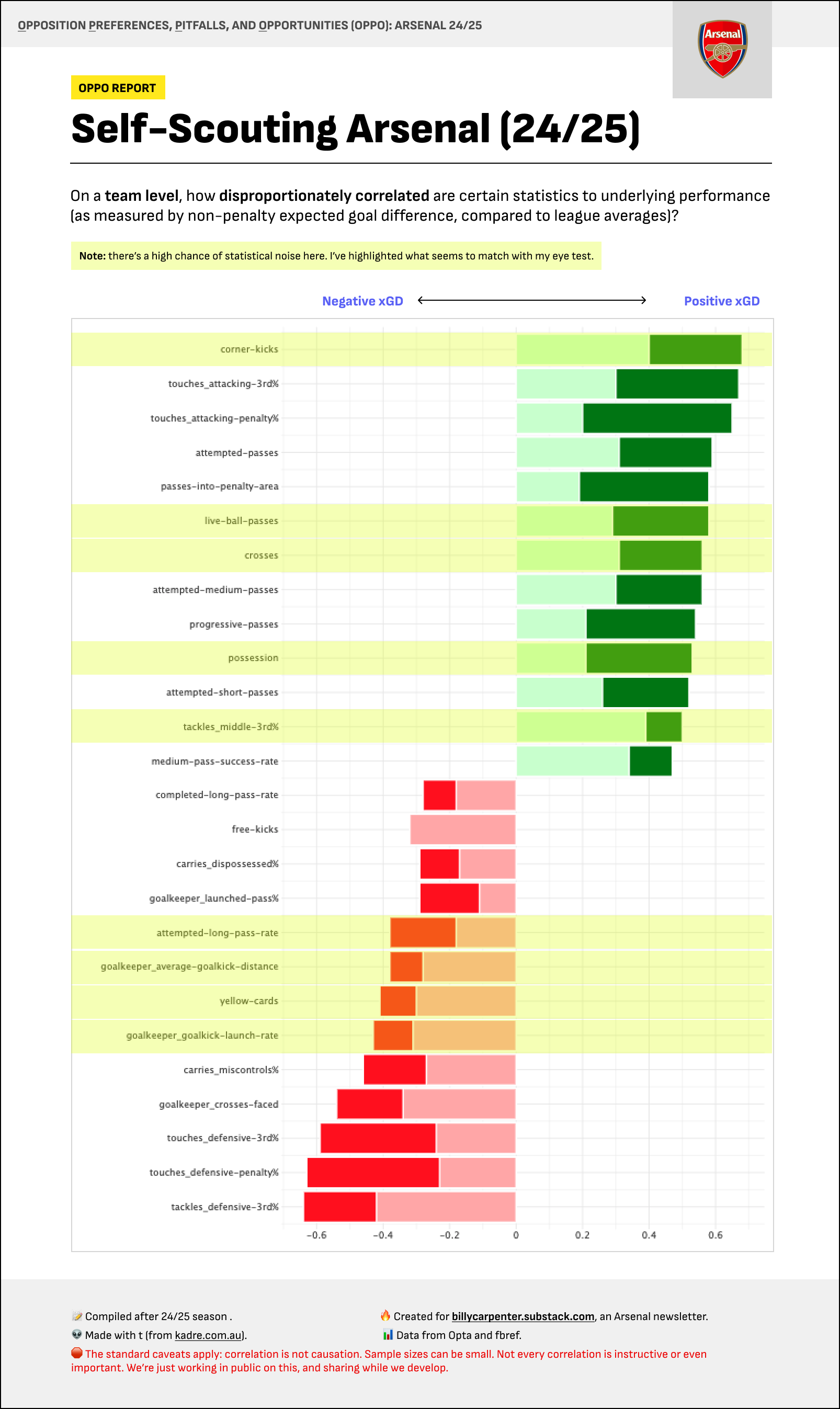

👊 Self-scouting Arsenal

We can dust off our scouting tool, which is tenuously called OPPO: Opposition Preferences, Pitfalls, and Opportunities, and turn it inward.

To refresh, I’ve worked with a brilliant statistician named t (from Kadre) to bring this to life, and we introduced it at the end of 23/24. Here’s the overview from then.

To oversimplify, I’d wanted to do some correlation studies to see which statistics had the strongest relationship with the underlying performances of specific opponents.

For instance, if you learn that disrupting a certain kind of pass, or restricting a certain player’s carry, is disproportionately pivotal to a team’s performance, when compared to those in their league, then you can use that to focus your film study — and, ultimately, your gameplan.

Here were the caveats:

Correlation is not causation. Just because something happened more frequently, it does not mean it caused the underlying xG difference. “Just stop them from getting corner kicks and prosper!” is not the takeaway here.

Not all correlations are instructive or even important. It’s not all that useful to learn that teams tend to win more games when they shoot a lot. Key passes, assists, touches in the attacking third — these are all likely to come from dominant performances.

There are sample size limitations and general noise, particularly on statistics that don’t happen at a high volume.

On a team level, here were some of Arsenal’s strongest correlations last year. I’ve highlighted those that caught my eye.

What might we observe?

Arsenal have always fared disproportionately well with more corner kicks. That should only improve with GabiXL and Havertz back, Merino and Nørgaard getting minutes alongside them (compounding the advantage), and even White’s shithousery in the mix.

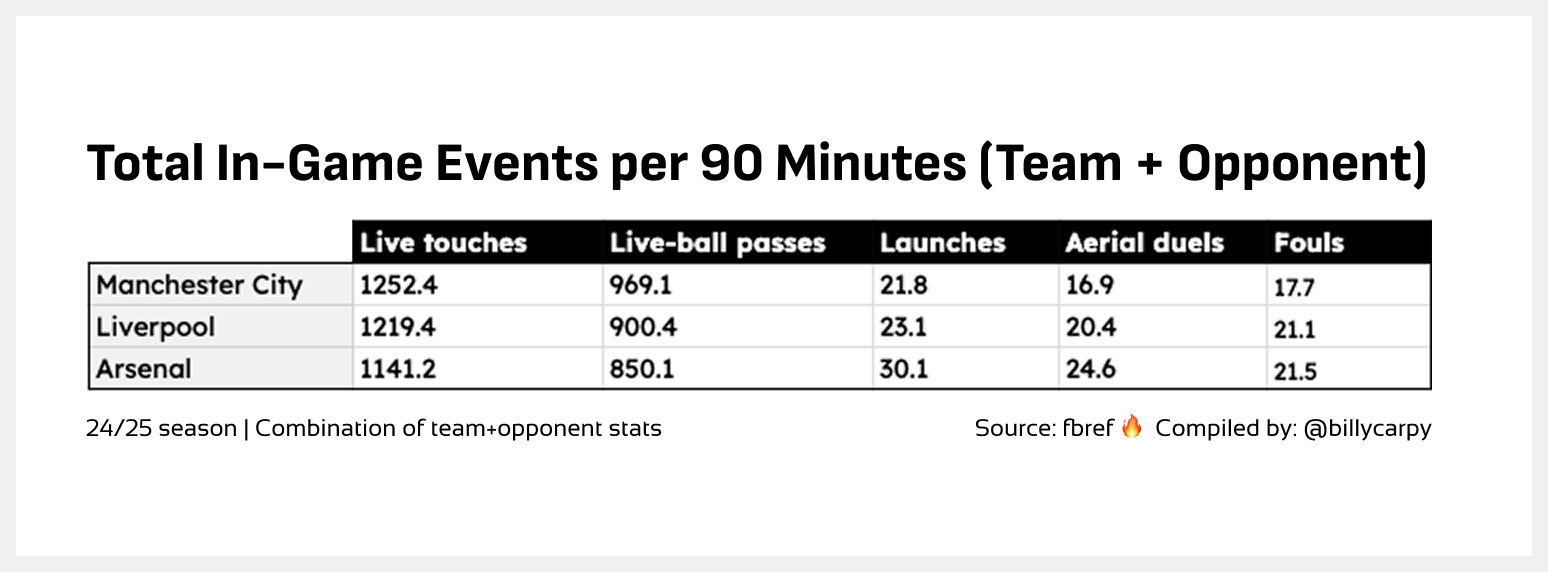

The more live-ball passes, the better. This will get covered later, but it’s one of my major focus areas: quicker restarts, shorter delays on free kicks, more playing through fouls. The objective is simple: get as many touches as possible to show your superiority.

Last year’s team did better when pinning opponents, and worse when sitting back. That’s obvious for most sides, but it was especially true for Arsenal. Two reasons: (1) we weren’t a good transitional team, which should hopefully improve this year, and (2) when protecting leads, we’d often drop into low blocks, absorb waves of pressure, and sometimes cough those leads up in seemingly random moments. More depth should mean a greater ability to keep intensity high.

Midfield tackles are another opportunity. As I’ve written elsewhere, you can set “midfield traps” to create transition chances for players like Gyökeres and Madueke. If Rice and Zubimendi are free to be aggressive in the challenge and move the ball on instantly, some of the chances that teams “deny” Arsenal will suddenly reappear.

I’d also like to see us launch the ball less from the keeper this season. We’re a good second-ball team, but it comes with issues: it takes the ball out of play more, takes longer to set up, isn’t fully controllable, and often stemmed from jerky build-up play last year. With Zubimendi around, there’s a better path.

On a player level, there was a decent amount of statistical noise because of all the chopping, changing, and absences. There were four players who I found to have correlations that were potentially interesting and meaningful.

Declan Rice: His strongest correlation to positive team performance was “tackles in the middle third.” Things also went well when he recovered the ball a lot, and, please: attempted crosses.

Martin Ødegaard: His strongest correlation to a good team performance was progressive carrying (interestingly); I’d thought he could be too prone to dead-end carries, but I suppose when he’s the free man in build-up, good things happen. The second-highest correlation to good performance was advanced tackles.

Gabriel Martinelli: His best correlation to good performance was “% of touches in the advanced third;” his worst was “% of touches in the middle third.” That makes sense on its face: the less he’s tasked with dragging the team up the pitch, and the more he’s floating and running and shooting, the better.

Kai Havertz: The team did particularly well when he completed medium passes. We did poorly when he got fouled too much, and when he had too many dribbles and carries.

👉 What’s changed this preseason?

When you go through preseason data, the most important thing to remember is how unreliable it is. The starting midfield trio in the first match was Nørgaard/Rice/Nwaneri; in the second, it was Zubimendi/Merino/Nwaneri. The Newcastle game ended with a Nichols/Dowman right side and Annous up top. Even when the lineups looked closer to a likely starting XI, the timing didn’t always match the opponent’s strongest lineups. It’s all messy.

It wasn’t until these last two games that we got a look at what’s probably the first-choice midfield: Zubimendi, Rice, Ødegaard. For all the talk of rotation, I find it hard to see that trio benched in big games, unless it’s down to knocks or fitness.

The other thing is: if you go looking for something in football, you’ll usually find it. Think a player is lazy? You’ll notice the walks, even if they’re covering more ground than anyone else. Think a player is mistake-prone? You’ll remember the stray passes, even if they had no impact. And if you’re hunting for changes in preseason, you’ll find them … whether or not the team actually played much differently.

Early on, the setup and tactics looked pretty familiar. The clearest shifts were Zubimendi pushing unusually high from the #6 spot, and some new, experimental set plays. Otherwise, the passing patterns and tempo were much the same.

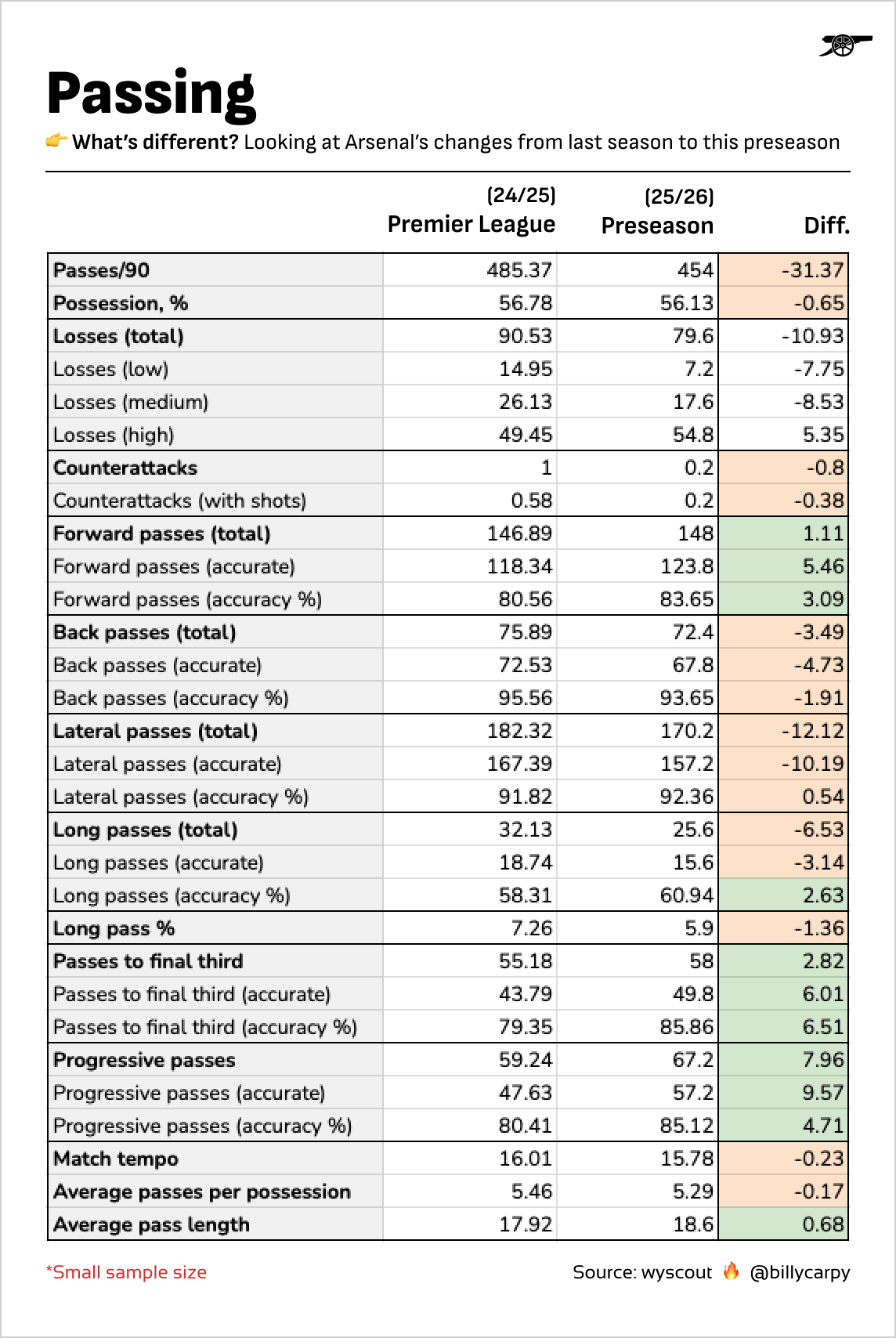

Still, I pulled all the league numbers from last year and compared them to this preseason to see if anything interesting jumped out, and whether any of the commonly held truths might need adjusting. Let’s start with passing.

A few observations from that:

I wouldn’t put too much stock into the “fewer passes” statistic. Possession stayed the same, and there were a lot of stoppages for subs, fouls, and the like.

Arsenal lost the ball far less in low and middle areas, but more in high areas, which is probably a good sign.

One simple takeaway from comparing last year’s Liverpool tactics: they kept the ball in the middle third more, preserving space to attack when the time was right. They did it through more forward-and-backward passing and less lateral passing. Something to look for this year is fewer launches, more ball on the ground, and more forward/backward passing. That’s been happening.

Contrary to what we might expect, long passing was actually down, and match tempo was about the same. So we can’t say conclusively that they’re going long more, switching more, or dramatically speeding things up. Both are noisy stats, though.

The other encouraging thing was the increase in accurate progressive passes, despite 31 fewer total passes per 90 overall. The Zubimendi effect?

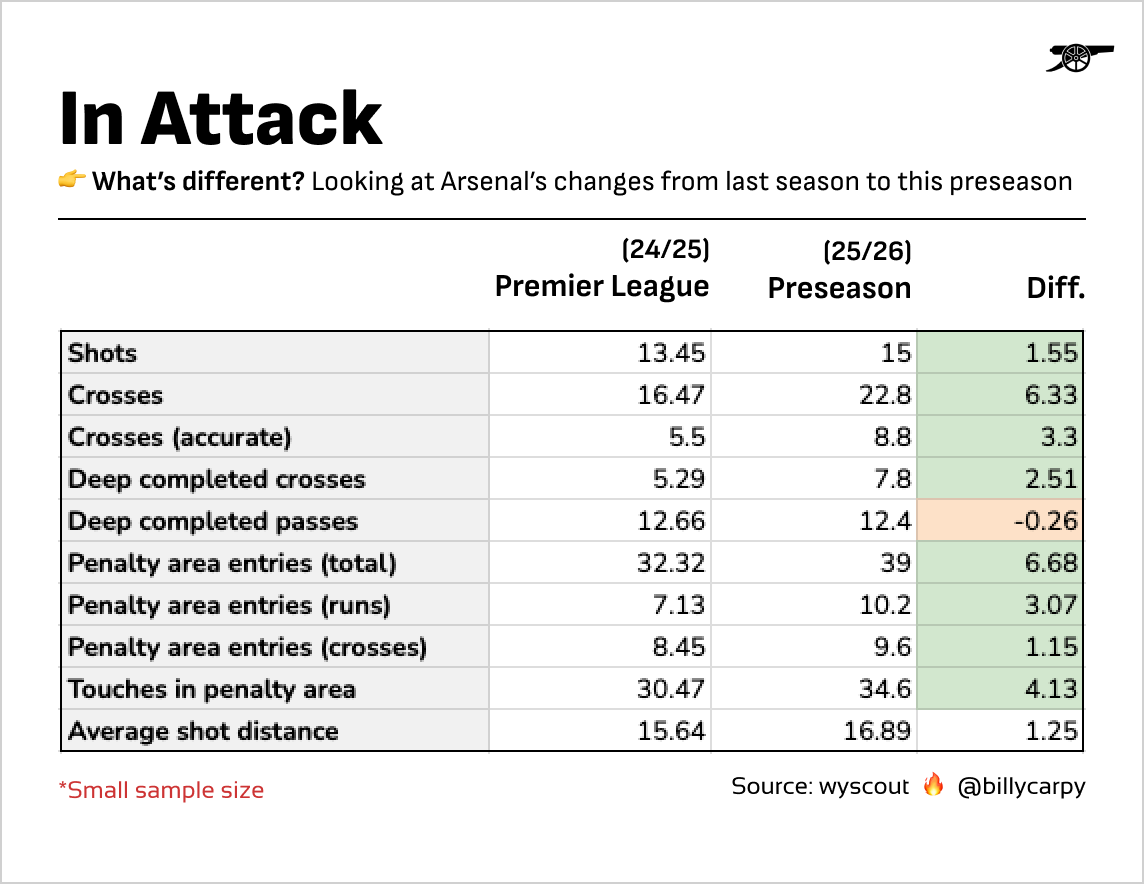

Next, let’s look at the stats closer to the box. To be clear, these numbers are a little more basic in variety.

This shows a marked increase across the board. The most interesting jump was in crossing. Noni Madueke looks like he’s going to send in a lot from the left, and Saka already does plenty from the right. We’ll come back to that later.

The overall shot profile, though, was poor, as was the ability to generate total xG at the levels we’d like. Plenty of Arsenal’s preseason stats were impressive, but the ability to consistently create high-quality chances wasn’t there. It looked better with the first-choice midfield, but it’s still the biggest question heading into the season, and we shouldn’t just hand-wave it away.

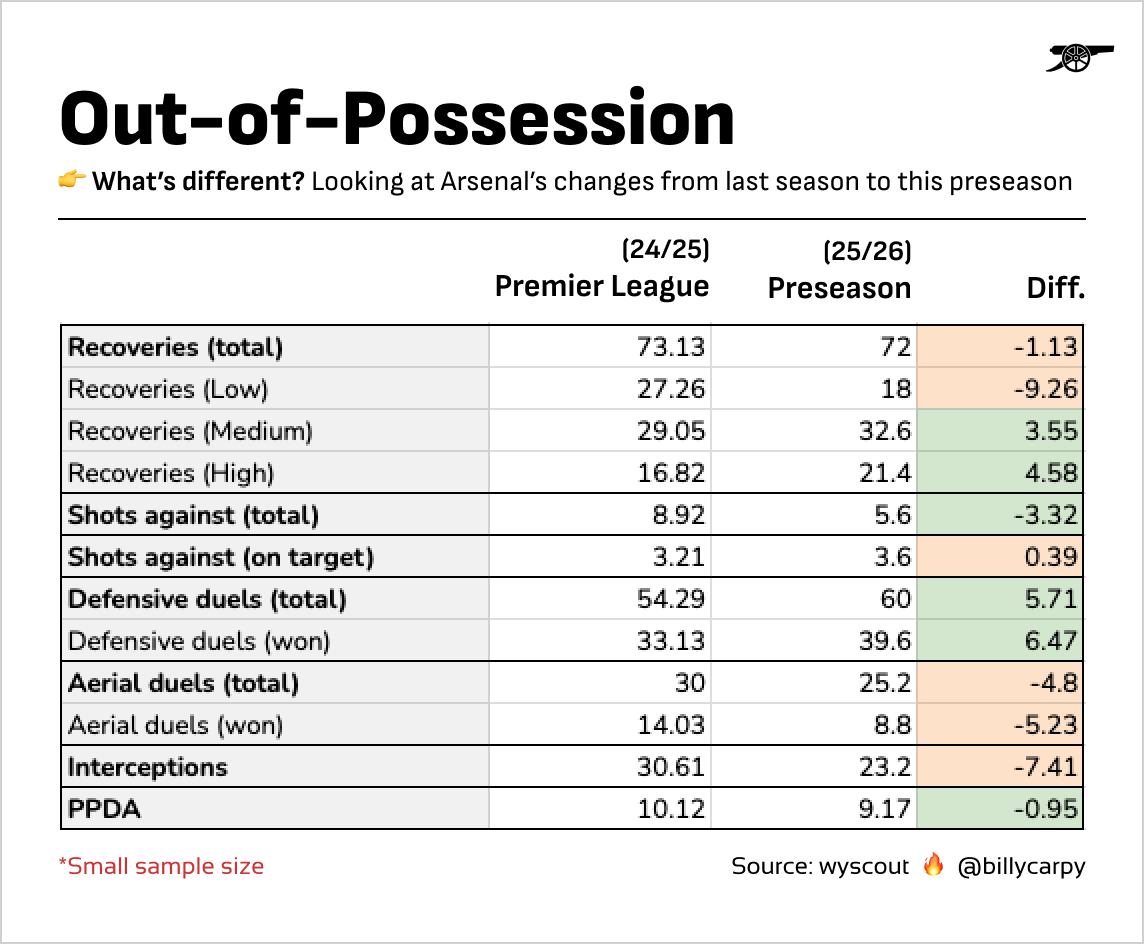

Finally, we can look at the out-of-possession side.

In general, that looks pretty good. In practice, we did see a couple of those quick, against-the-run-of-play goals we’ve been stung by in past seasons, and hope those continue to fade away as players get older and partnerships grow rock-solid. But you can’t read too much into that, given all the rotation and new connections forming. By and large, the defensive performance was solid.

🎉 The new midfield

The final preseason match was more interesting tactically than the other four combined. We finally saw our first-choice midfield in a real, even-game-state setting.

And it was beautiful.

A lot of it is built around the complementary qualities of Declan Rice and Martin Zubimendi. Said Arteta:

“Especially with the qualities that they have, and the way they can complement each other in that space, we saw another evolution today on that and things that the team can really benefit from: to be much more unpredictable and be a much more threat, especially from these inside positions.”

I’ll be real with you: I’m gobsmacked by what we’re seeing from Zubimendi, even moreso on rewatches. I have some lingering issues with other parts of the window, which may still get addressed, but I’ll start with that hot take: I think Zubimendi is going to contend for the Premier League XI. He probably won’t make it, not exactly, but I think he will stake his claim as one of the higher-echelon players in the league.

Without a single league minute to his name, I’m ready to skip the bear case in his profile and go straight to the bull case:

In this scenario, he joins early, steps in, improves our ability to play out, controls tempo, and lets us toggle between speeding up and slowing down as needed. The draws turn into wins, because the leads stay leads, and the 1-0’s turn into 2-0’s and 3-0’s.

With more talent around him, his touches could increase and his final-third metrics could nudge upward. A few more assists, cleaner key pass numbers, maybe a couple goals from second phases in set plays. In a more domineering side, his numbers will reflect that. It’s not hard to see him with 90% pass accuracy, uber-efficient defensive metrics, and big touch counts.

He is not just a cog, but a force multiplier. His presence could raise Arsenal’s floor (bad games are less bad because he ensures some control) and raise their ceiling (good games become dominating ones). He’s the kind of player that can make those around him appear better by structuring a game on our terms; there’s a little bit more snappiness to action, there are fewer mistakes, and the attack jumps a level.

Why so optimistic, so soon, even though we know preseason has its asterisks? I shouldn’t get too ahead of myself, as he still has to do it in the league.

But my optimism is mostly due to how he’s being deployed, and how he’s deploying himself.

He has two modes, historically. One style of play is that of a humble servant. He was often that for Real Sociedad: the floor-raiser, the seat-filler, the support outlet, the player who pulls shadow-markers around so others can prosper. He has another style that we’ve seen more with Spain: the all-action metronome, simultaneously slowing things down and speeding them up, greedy about getting involved in higher, more dangerous areas. The first is like an even stealthier, subtler, quieter Jorginho; the second role is more like Rodri’s deployment in his Ballon d’Or year, though with fewer touches. To be clear, I’m not comparing levels, not exactly, just talking about locations.

Within a few minutes of his preseason debut, it was clear which self he was bringing.

Door number two.

In previous games, we saw the left-back invert and the LCM push higher. That works in matches where we want to more reliably pin or outnumber the backline. The #6 has often been pretty “lone,” with the LB going in or out based on the placement of the opponent block. This is a little clunky of a diagram, but gives you an idea.

When together, Zubimendi and Lewis-Skelly have most of what you’d want in a double pivot: carries, line-cutting passes, tempo control, short combinations, and defensive duels. And with Zubimendi in, it’s less of a “problem” to have Rice high than it was previously. If the previous #6 couldn’t make an immediate tackle, he used to drop into the backline in transition instead of breaking up counters at the source, which gave players like Morgan Rogers the license to run amok.

Still, I think we all can agree that having Rice in a more static, high, low-touch, pinning role probably isn’t the best use of his talents. The goal is to unleash him into a more cocky, aggro, fear-inducing player in attack.

Against Athletic Club, we saw something different, and it wasn’t fully unexpected, but it did feel like a revelation. The simplest version: Zubimendi generally sat as the deeper man in the double pivot, but Rice and he “see-sawed” back and forth, and Raya was generally taken out of the equation.

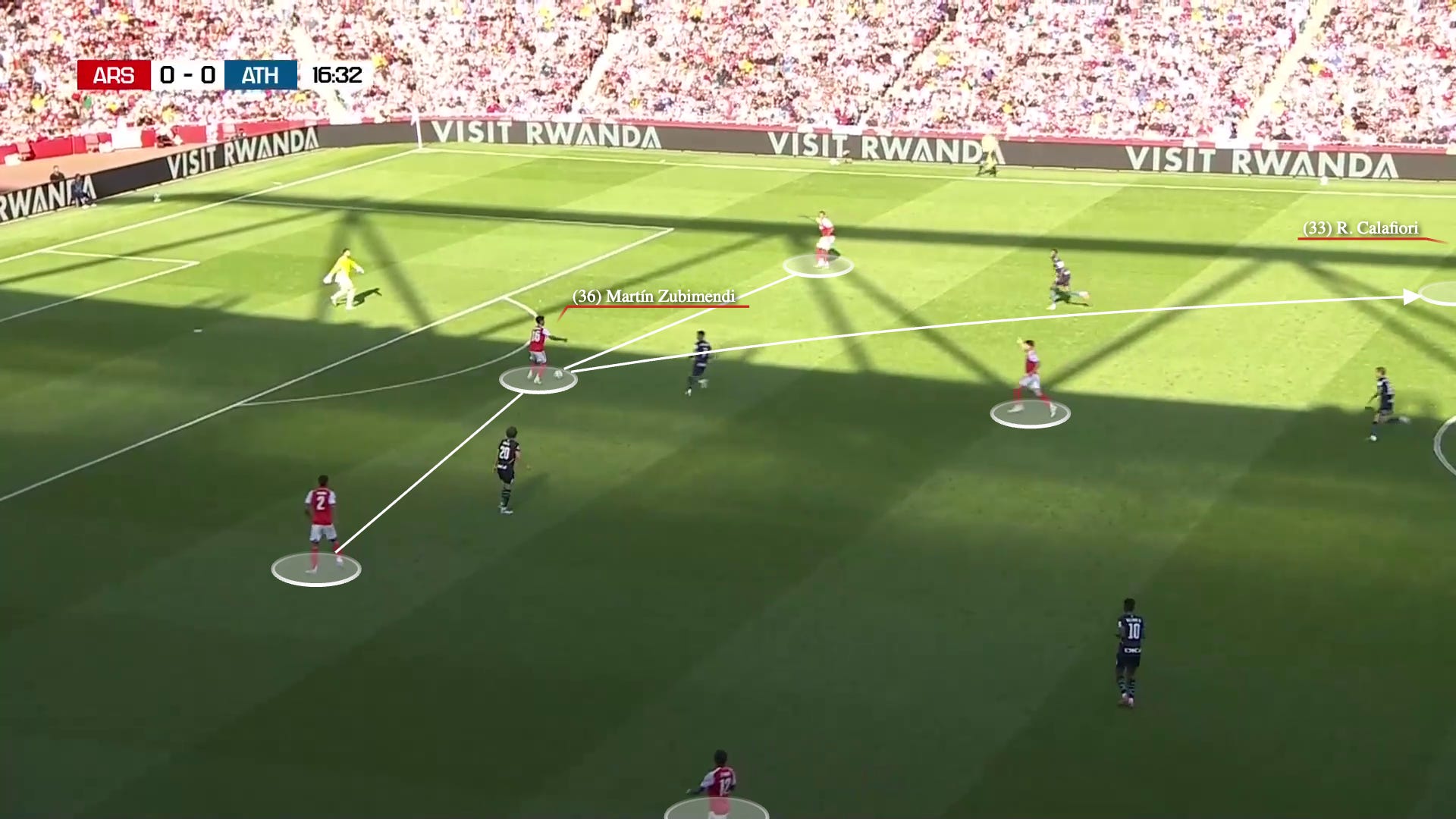

But interestingly, the first midfield touches showed something different: Rice dropping deep to collect, Raya hanging back, and Ødegaard and Calafiori acting as the two advanced midfielders. They roamed above the pivot, tracked the movements of Zubimendi and Rice, and looked for small gaps to receive, so they could turn and carry.

You could also see Zubimendi dropping to split the centre-backs in moments like this, which is something we frequently saw at La Real. In this case, Rice told him to play it wide and Gabriel signalled for a pass back to Raya. Zubimendi shaped his body as if he was about to do one of those things, then whipped it up to Calafiori instead.

But the full weight of his responsibilities and qualities came through most clearly in the next gif. He set the timing of the build-up, slipped between the front two, turned and drove forward, broke a line, stopped a counter, and then tackle-passed another. A few seconds later, it led to a good opportunity.

I’d joked that much of the discussion has focused on how Zubimendi could potentially unlock Rice, but I’d argued the reverse: what if Rice unlocks the full version of Zubimendi? A place next to him is a nice offering, and the early signs are good.

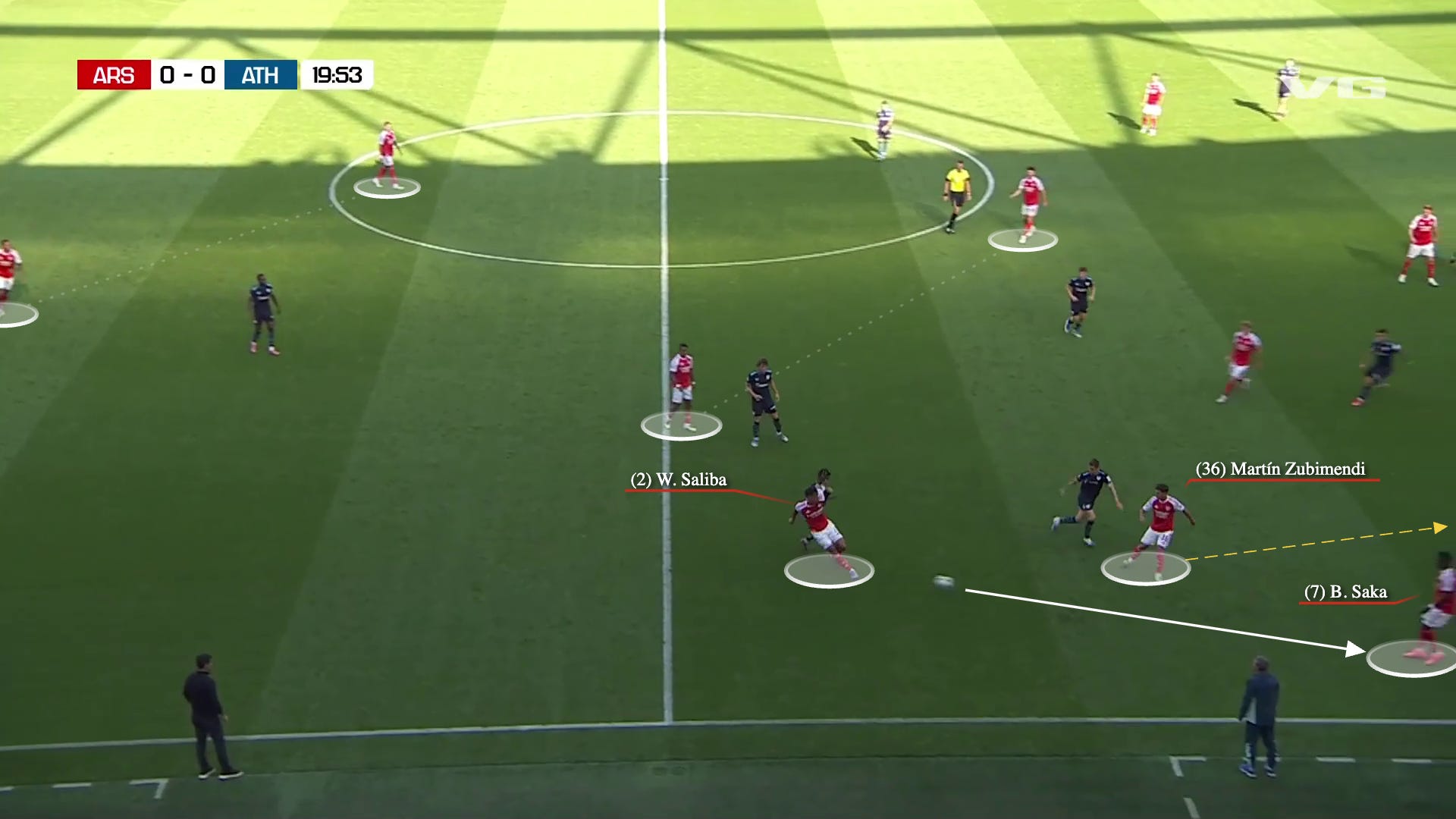

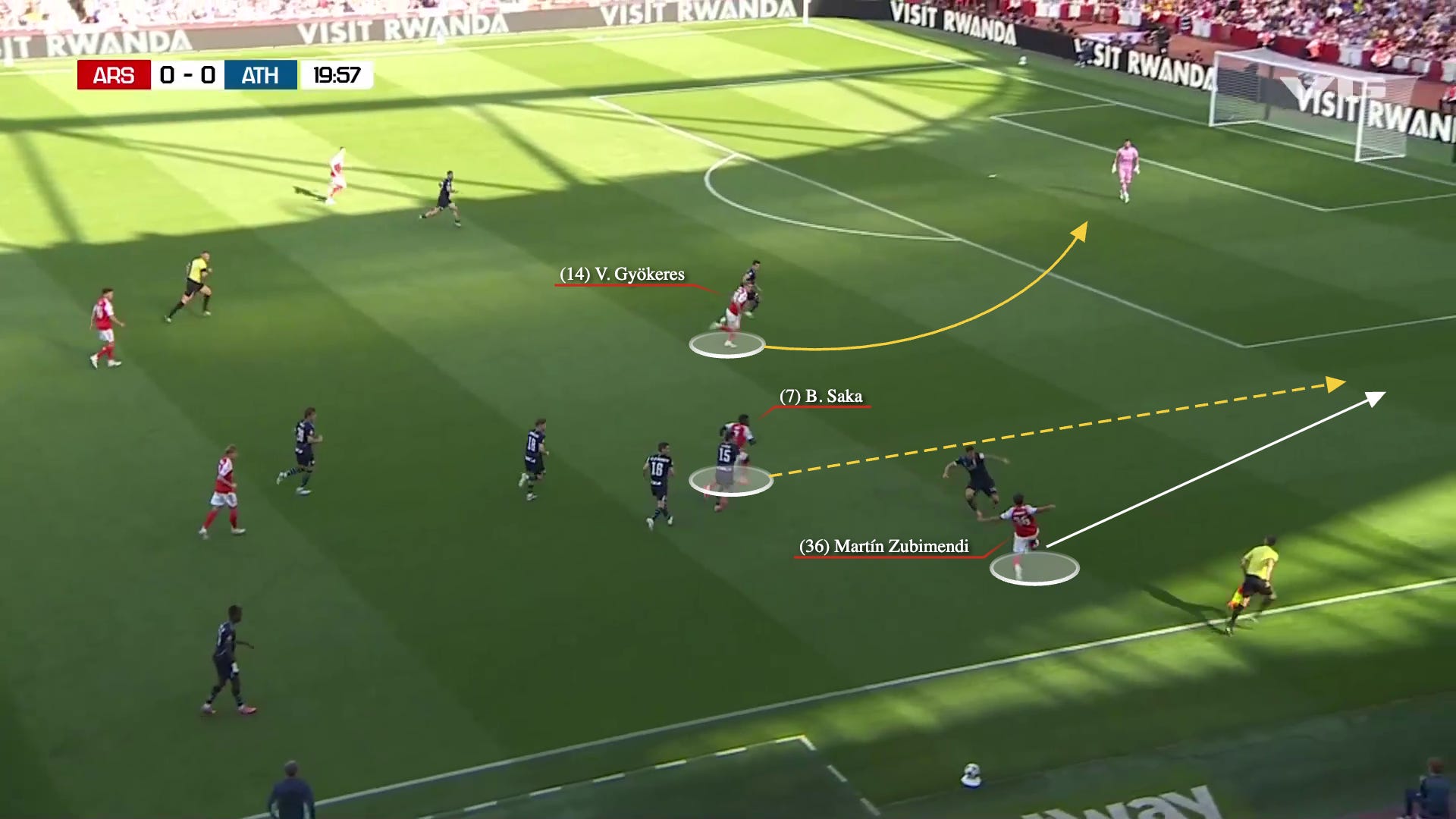

Here, after a regain, Arsenal chose to force the issue rather than fully reset. Timber and Rice formed a “net” to collect any loose balls, freeing Zubimendi to operate however he wanted.

Saka then does Saka things, receiving the ball and drawing a triple team. Zubimendi, with deep cover behind him, sneaks into the space usually occupied by a right-winger.

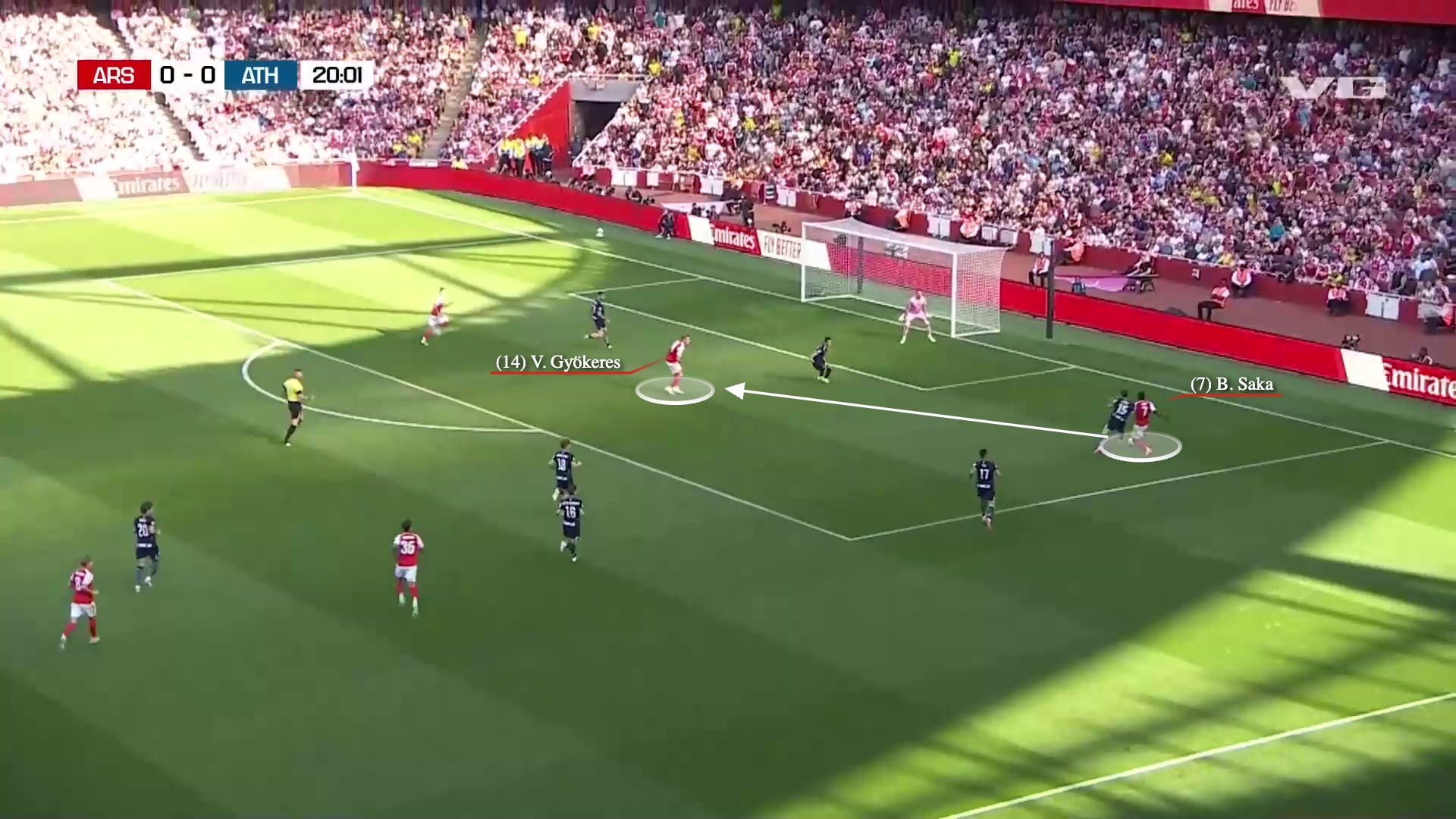

He then draws the defender in and toe-pokes it into space for Saka, with Gyökeres bending his run toward the spot.

By the end, Gyökeres sprints toward goal, then pulls up to find space at the penalty spot. Saka delivers it perfectly, but Gyökeres scuffs the finish.

Football is funny. Gyökeres’ first goal for Arsenal came from a header, after scoring exactly zero of them last season. He was free and made a smart run. That part will continue; the remaining question is more about how he fares in touch-tight contested, physical aerial duels against settled Premier Leaguers. In any case, these (^) are the kinds of goals I expect to stack up for him here: he’ll get plenty of chances in spots like this, and I don’t think he’ll scuff many.

Meanwhile: an undercelebrated, vaguely-understood quality in a No. 6 is the ability to manipulate the block as an off-ball presence, something that’s quietly been an issue in recent years. It’s about more than constantly showing for the ball.

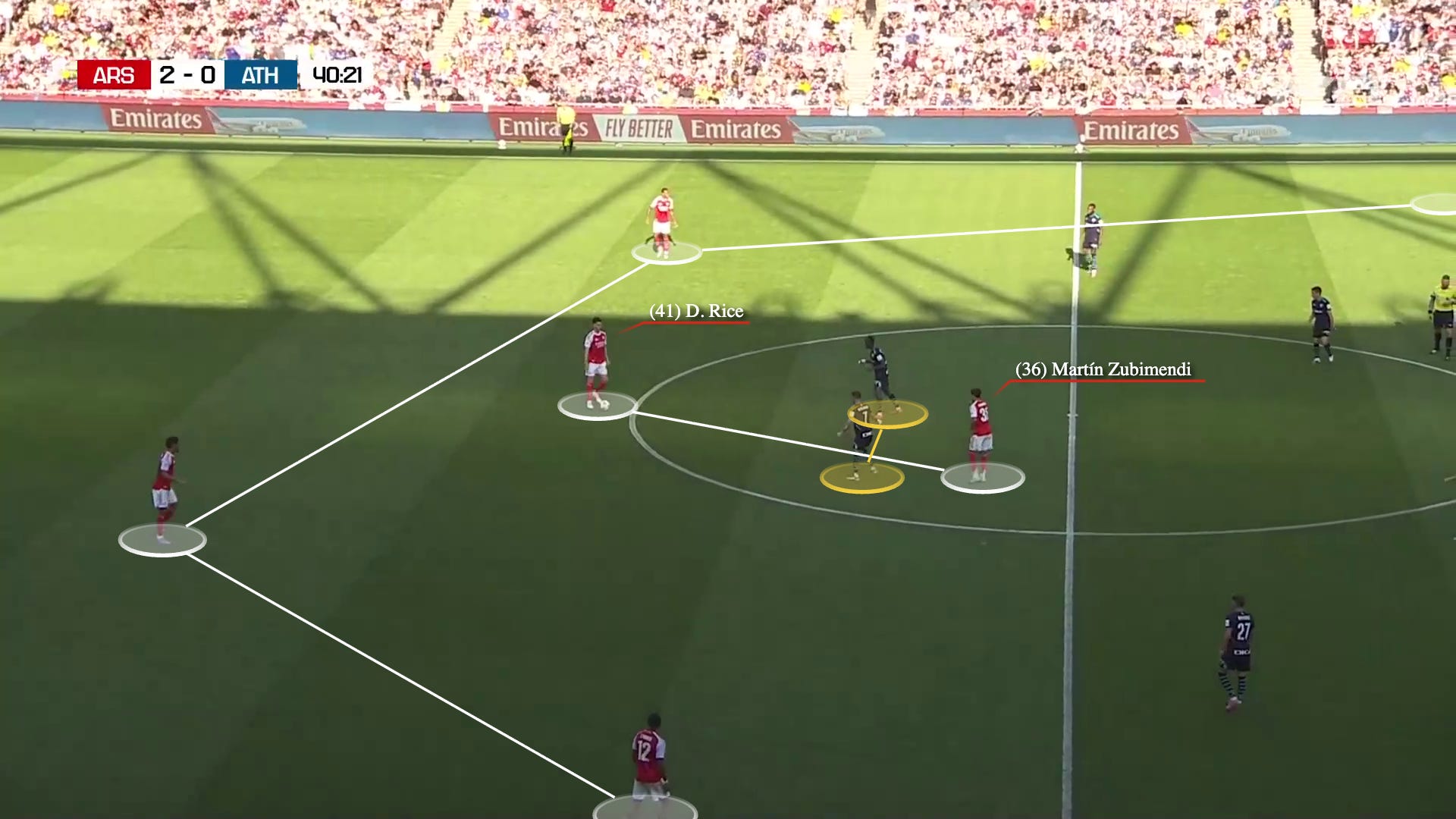

This is where Zubimendi is almost mischievous. Here, he’s looking to poke through the front two. Even if you can’t thread a ball there, you can make the defenders so narrow that lanes open elsewhere. At worst, it gives time for somebody like Timber to receive, and makes these two hesitant to jump at Rice.

Here’s another look at that in a more typical situation.

Rice is drifting back into the double pivot while Lewis-Skelly and Ødegaard float just ahead of it. Zubimendi is scanning left and right.

From there, he spots jump of the forward, disappears into the gap, slips in behind, receives across his body, and pushes it forward. The result is an isolated Saka 1v1.

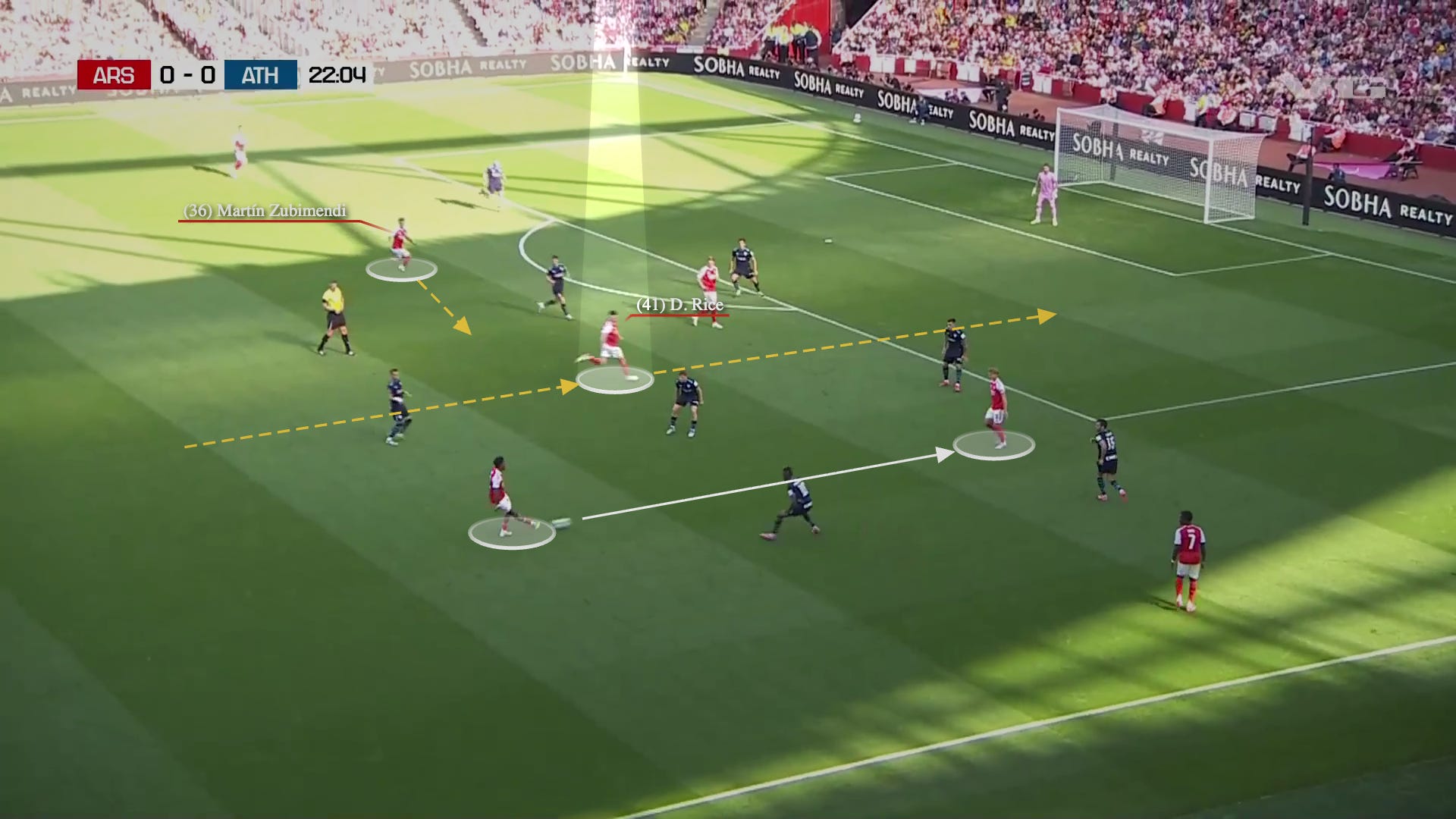

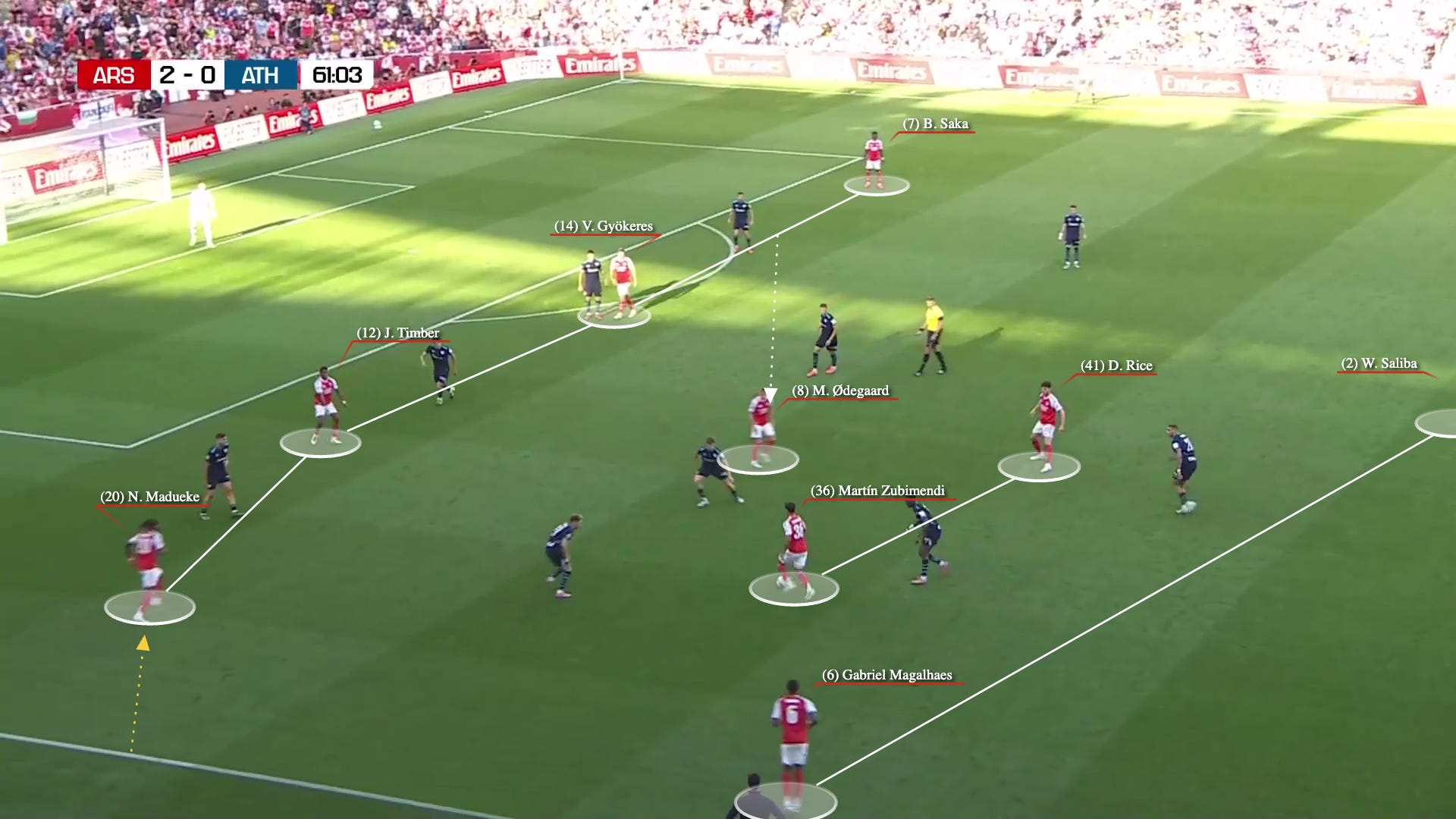

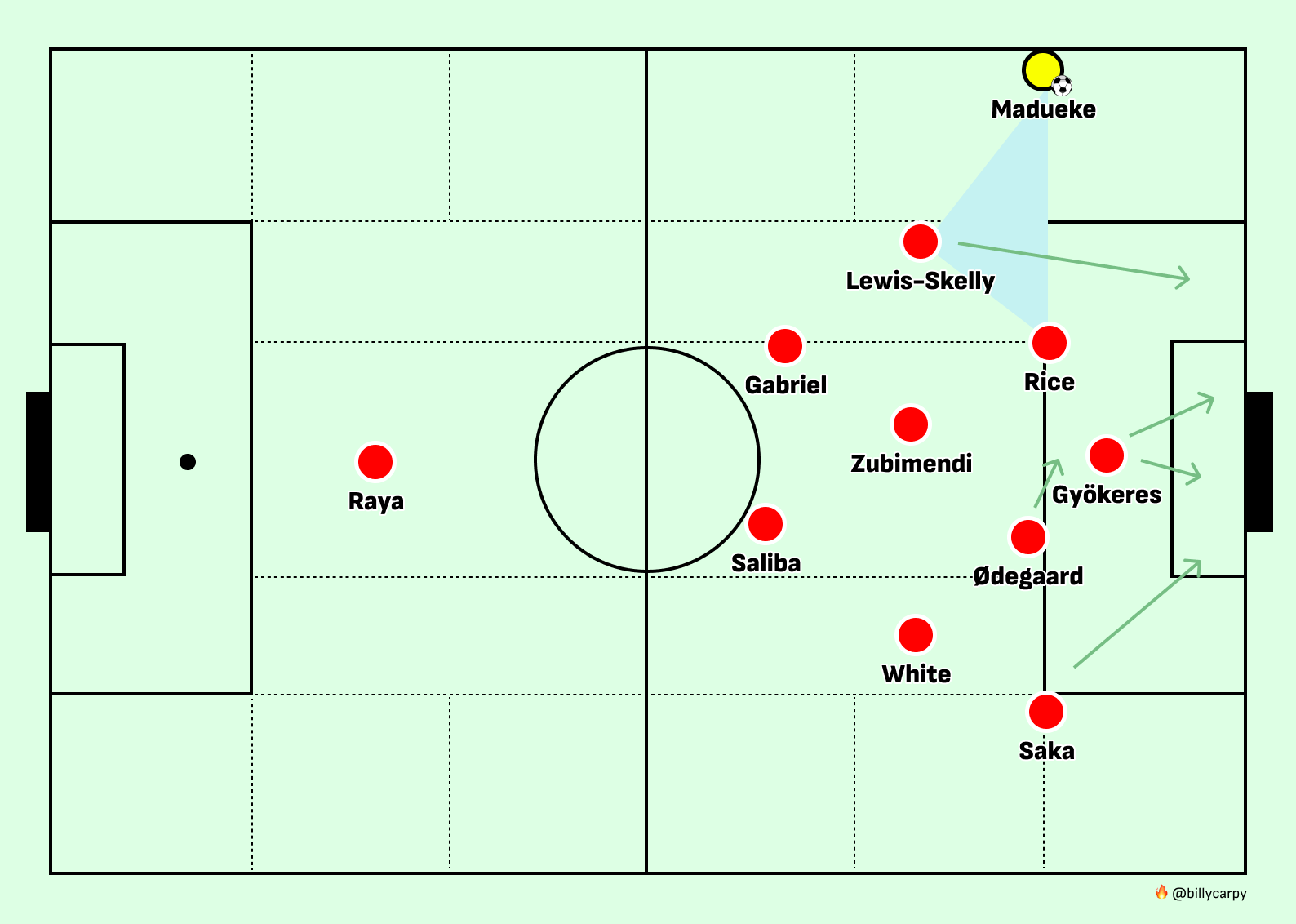

This next example starts from a typical setup, but shows how it can expand into new and interesting possibilities. This is the screenshot we opened with:

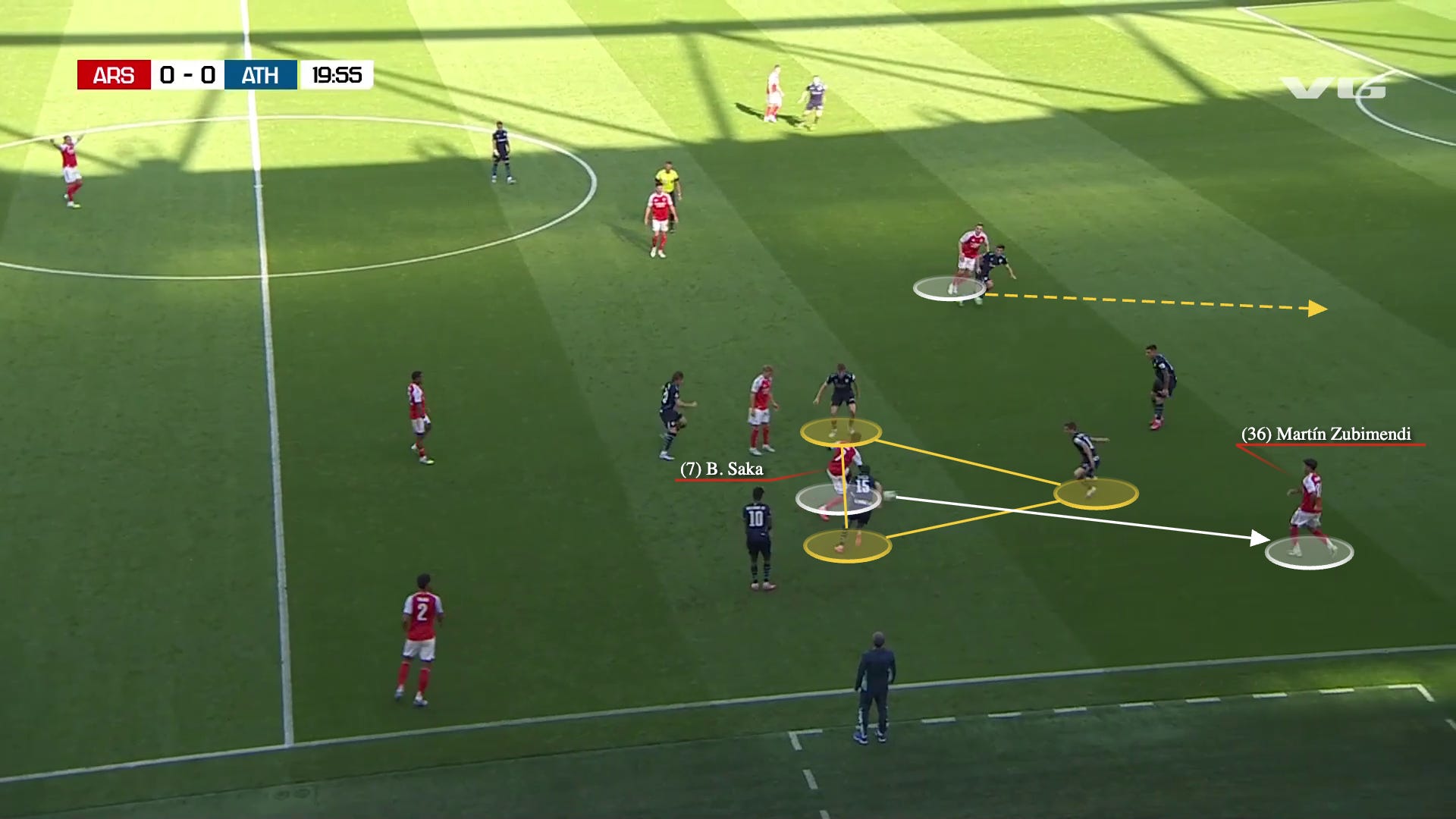

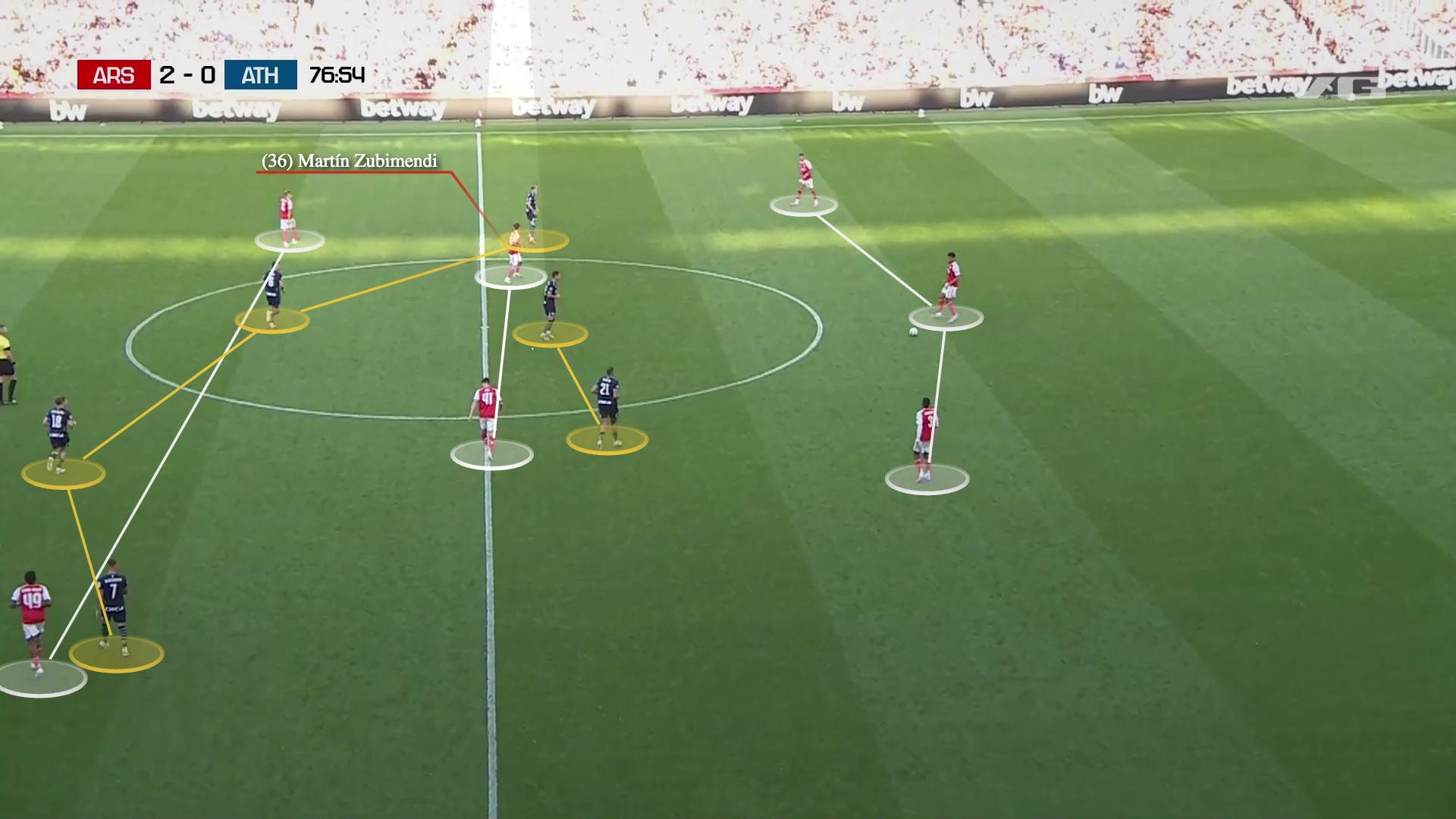

Zubimendi carries around the bend and spots the chance to bait Athletic Club into stepping across to halt his run. But they don’t really bite, and Rice drops in underneath to cover the middle ground as play resets. They’ve now switched sides.

After the reset, we get a wide triangle of Timber, Ødegaard, and Saka. Timber plays it into the captain, and because Zubimendi spots what’s developing, he can rotate through the middle … while Rice bursts in on a violent underlap.

This is the kind of high touch and ambition that was too rare from the No. 6 spot last year, when the default was to drop and cover; Rice always felt too risk-averse and simplistic when he was there, and has shown plenty of interesting runs and arrivals on the right, for Carsley with England and occasionally at Arsenal. Now, with two players who share similar qualities, both are looking for every opportunity to impact the game more forcefully.

We can see that here. This high positioning came through from Zubimendi’s first minutes, and it came from Zubimendi checking his shoulder for coverage before stepping in. Rice was behind.

And this can turn into bodies in the box. Whereas this would just be the LCM (Rice/Merino/Xhaka) previously, this probing can be done by both members of the double-pivot now. Here, Rice is sweeping behind in the case of a loss, and can arrive to the edge of the box for a banger if needed. Zubimendi back-heels a rebound to Havertz:

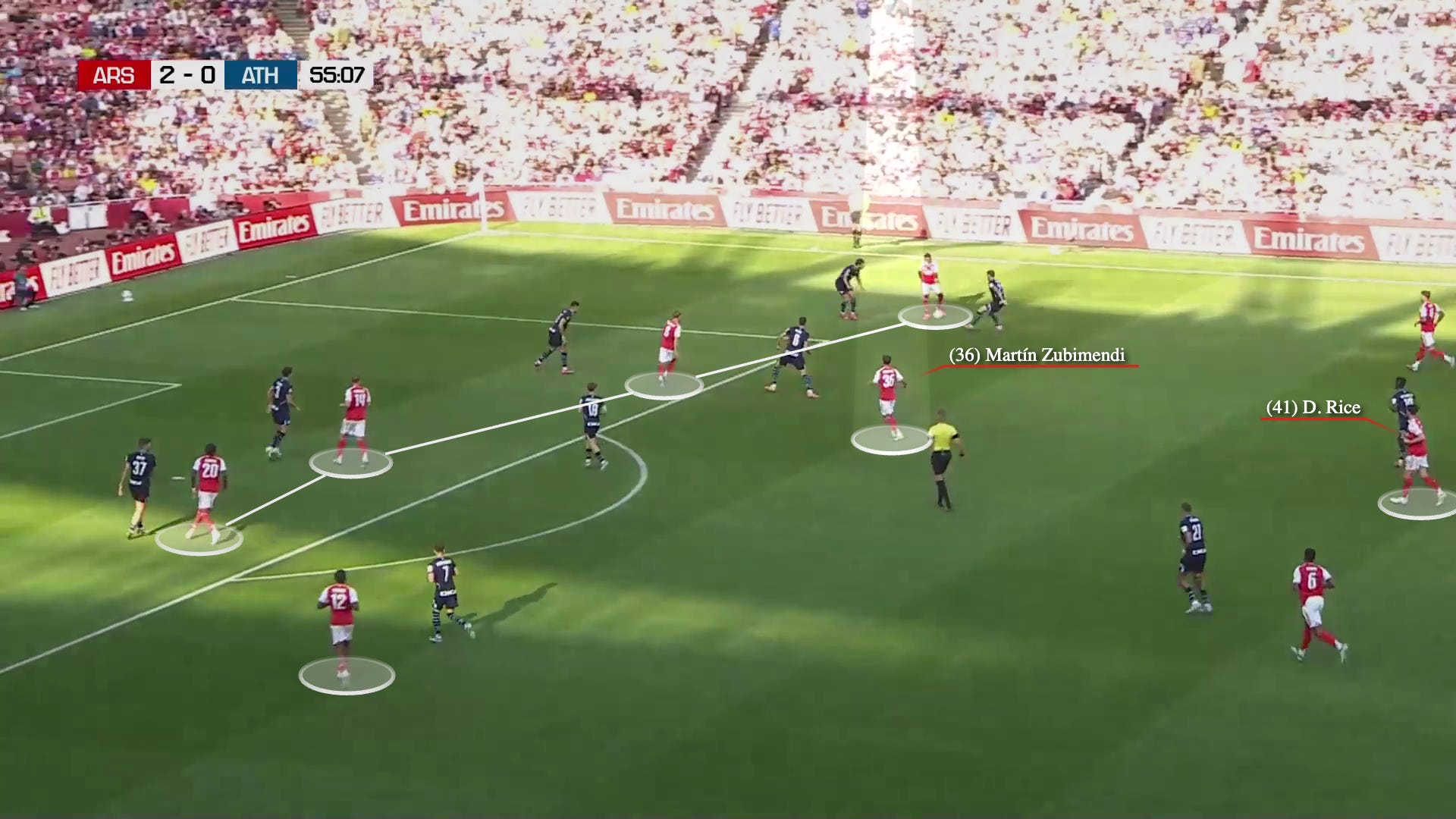

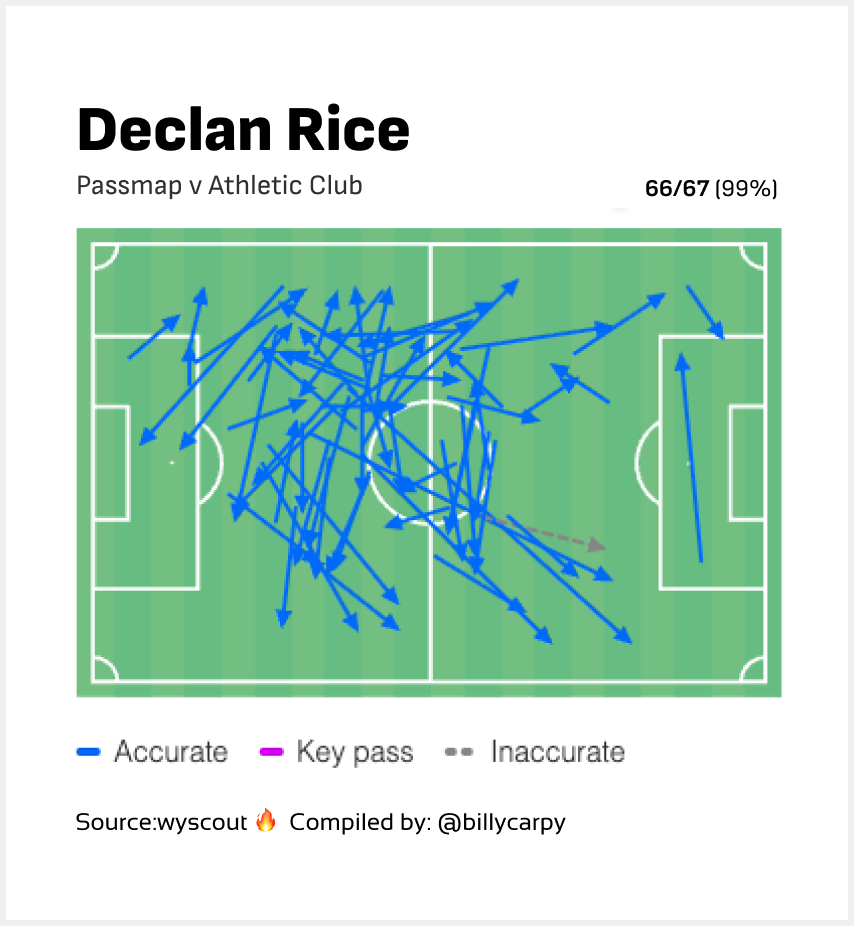

As a result of all this, Rice dropped deeper into something resembling a double-pivot 6/8 hybrid. He ended up playing from a lower position than usual but still completed 66 of 67 passes. It’s no surprise Athletic Club had such a hard time getting out of their own half. You’d still probably like him to have a bit more advanced activity, but there was no breaking through this kind of fortress for the opponent.

This “net,” the two of Zubimendi and Rice through the middle, has so much potential at stifling teams in an increasingly physical, end-to-end league.

Just to give you a sense of what we’re talking about, here’s Zubimendi’s final stats in that match, per wyscout:

60/63 passing

24/25 forward passes

5/5 long passes

12/14 duels won

9/9 defensive duels won

15 recoveries

3 interceptions

2 key passes

1 assist

There are real physical tests to come. So we’ll see if I have to readjust and add some nuance to all this.

I expect to see multiple iterations of the midfield, dependent on the opposition's pressing setup. Don’t be surprised to see Rice in a higher role again. But right now, if you were to ask which one I like best, it’s what we saw here: a Rice/Zubimendi see-saw pivot, with Calafiori trouble-making as much as he can around them.

📣 The new voice: Gabriel Heinze

In Amy Lawrence’s profile of Arteta for The Athletic, one quote stuck with me:

“There is much more to come. Because the manager that the boys needed three years ago is a different manager than they need today. The team has grown so much in every sense of that word that they need somebody else, and that somebody else has to adapt and identify what is really important, what is really going to get that fire in the belly to get the best out of them. That’s the evolution of the manager.”

The idea that the team needs a different coach than they had a few years ago is an interesting one. And one of the clearest ways that has shown itself is in the staff around him.

Carlos Cuesta has departed. The 29-year-old Spaniard recently left Arsenal to become Parma’s head coach, taking his place as the youngest gaffer in the European top-five. Cuesta was something of a prodigy, an overachiever who plied his trade in one-on-one tactical and technical work. He was multilingual, meticulous, and data-driven, tailoring feedback to each player’s needs, as we saw in All or Nothing, where he came across as calm and emotionally attuned. He was very much of the modern generation: academic, detail-obsessed, and analytical.

I was always impressed by how much he won over Granit Xhaka, his elder.

“My feeling from the first meeting with him was that first of all, as a person, he is very honest, very straight,” explains Xhaka. “But he also had great knowledge about football. He knows what he’s doing: he knows how to speak with the players, what the players need. It was just amazing from the beginning … The individual meetings that we had with him were always on point, very clear to understand, and I was very grateful to learn many many new things.”

To fill this void, Arteta didn’t opt for a like-for-like replacement. Instead, he brought in Gabriel Heinze, a 47-year-old veteran who played at an elite level and has since managed in Argentina and Europe. The difference is obvious in style and presence. Cuesta was cerebral and methodical. Heinze is passionate and demanding.

It’s a shock to the system, which I gather is the idea. Reports James McNicholas:

The new assistant coach has made a big impression on the training ground — he is forthright, direct and frequently loud. Certain players relish that coaching style; for others, it requires some adjustment.

His career, and the training photos already circulating, are defined by intensity. At Manchester United, he learned the uncompromising standards of Sir Alex Ferguson, even if their relationship ended poorly when Heinze tried to move to Liverpool. At Roma, in his last year in Europe, he played under Luis Enrique in a possession-heavy system that pushed defenders to hold a high line and stay comfortable on the ball; this style was reportedly influential to his ideas of possession-based play. With Argentina, Marcelo Bielsa’s relentless pressing left a lasting impression, even if Heinze insists comparisons are unfair. These experiences exposed him to different schools of management: disciplinarians, tacticians, idealists, and combinations thereof.

Heinze had other personal ties in today’s coaching world. He was a teammate of Arteta at PSG, and Arteta has spoken about how Heinze (and Mauricio Pochettino) looked after him as a young player arriving in Europe.

Accounts from his coaching career are fairly consistent. At Vélez Sarsfield, Heinze built the stingiest defense in Argentina, conceding fewer than ten shots per game in 2019, thanks to a compact shape and aggressive pressing. I just watched an interview during that time, in which he said the following (according to my questionable Spanish and the translation):

“I feel only one thing, which is: if I have the ball more than the opponent, I can do something. If I’m better than the opponent, then I have more possibilities. And for those things, there is only one way: to take risks. Because if I put three players to mark one opponent, there is no risk. You cannot change from a way of playing. You cannot tell a footballer, ‘today yes, tomorrow no.’ Because I don’t know how to coach ‘today yes, tomorrow no.’ You defend one way: I want the ball. The team wants the ball. And when the opponent has it, we are going after it. Not wait for them to make a mistake. Instead, we go to win it.”

At Argentinos Juniors, before that, he led a patched-together squad back to the first division in one season through sheer intensity. At Atlanta United, he clashed with players and was accused of overworking the squad, a sign of his stubborn streak. The Bielsa comparisons linger:

“I can say that there are similarities in their styles,” said one former player. “The fast transitions and the combination play in any sector of the field … there are similarities between the two coaches.”

I’m not temperamentally disposed to the yellers, but I also think that the only way to coach is through your authentic self; players can sniff out the “modulators” quick. For those who say Arsenal can feel too slow and predictable in possession, more concerned with control than striking quickly, Heinze’s ethos could be a useful counterweight. His teams were drilled to win the ball and attack with urgency, committing numbers forward before the opponent settles.

Ultimately, Arsenal didn’t hire Heinze as another analyst or sounding board. They brought him in to challenge players, and perhaps Arteta too, to push the team to a new level of intensity.

Oh, and his name is Gabriel.

🏃🏽♂️ Heinze’s impact: Intensity, immediacy, man-to-man

I shared a sad stat earlier:

Arsenal forced 100 more high turnovers than Nottingham Forest, and scored four fewer goals off them.

That’s a scare stat, and there are some explanations (injury, fatigue, opponent setups). But mostly, Arsenal a) didn’t win the ball back at the rates of seasons past, and b) didn’t turn those wins into shots as effectively as they could have. Heinze has likely turned his eyes upon this problem.

Above all, this came down to the qualities of the players themselves: Saka is sneakily a great off-ball runner (because he’s good at everything), but he was out for much of the year. Havertz, too. Ødegaard isn’t naturally a transition monster, and looked especially defanged last season. Martinelli missed some shots.

When the two highest players on a ball-win are, say, Ødegaard and Merino, you’re just not going to be a top transition team. This is evolving.

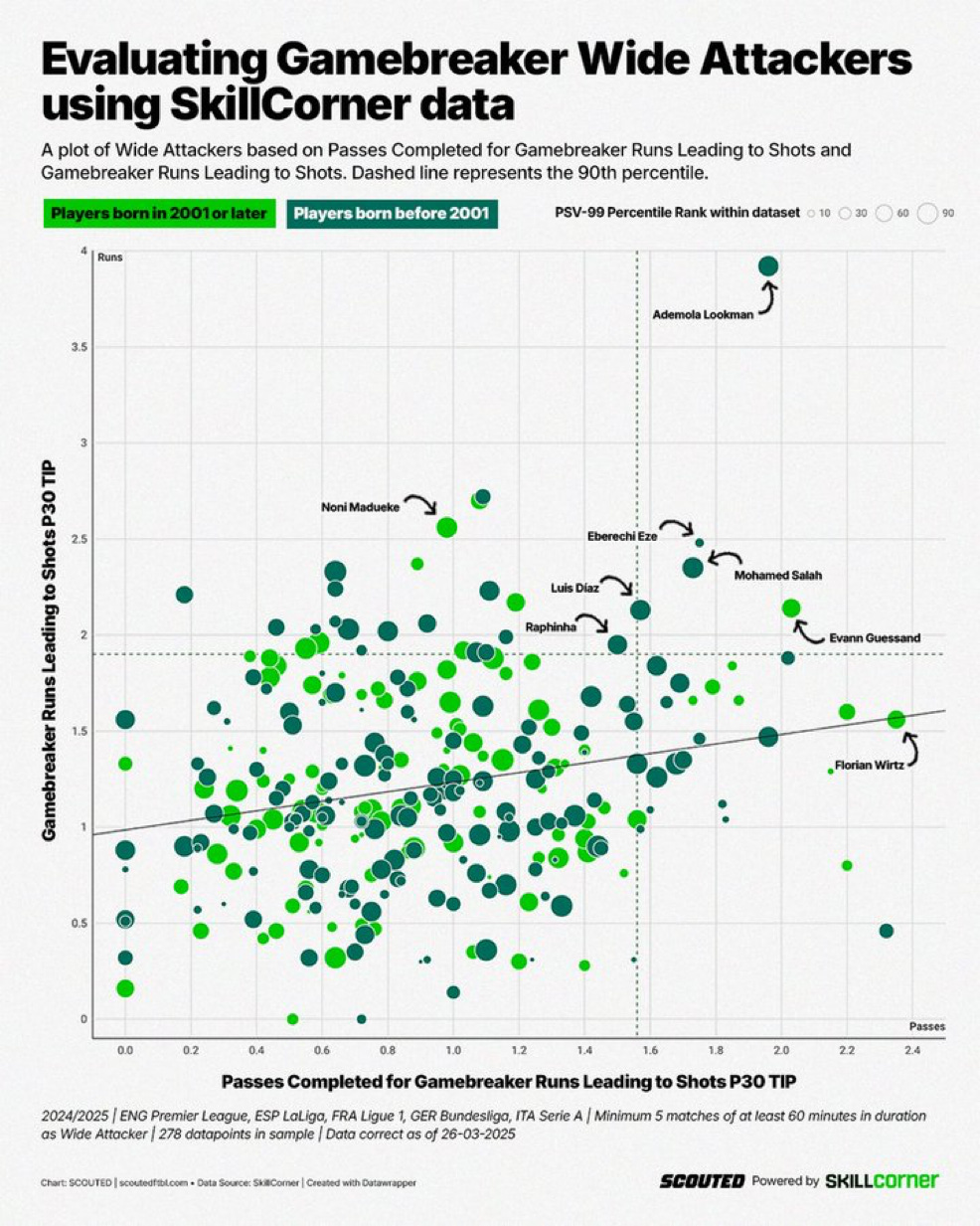

Next, I’m going to crib some of the charts I referenced in The House of Glass and Iron, my recent piece on Dougie Freedman’s recruitment legacy at Crystal Palace, and where they go from here. (Would encourage you to read that and join SCOUTED; it’s the best publication of its kind in the world, if you ask me.)

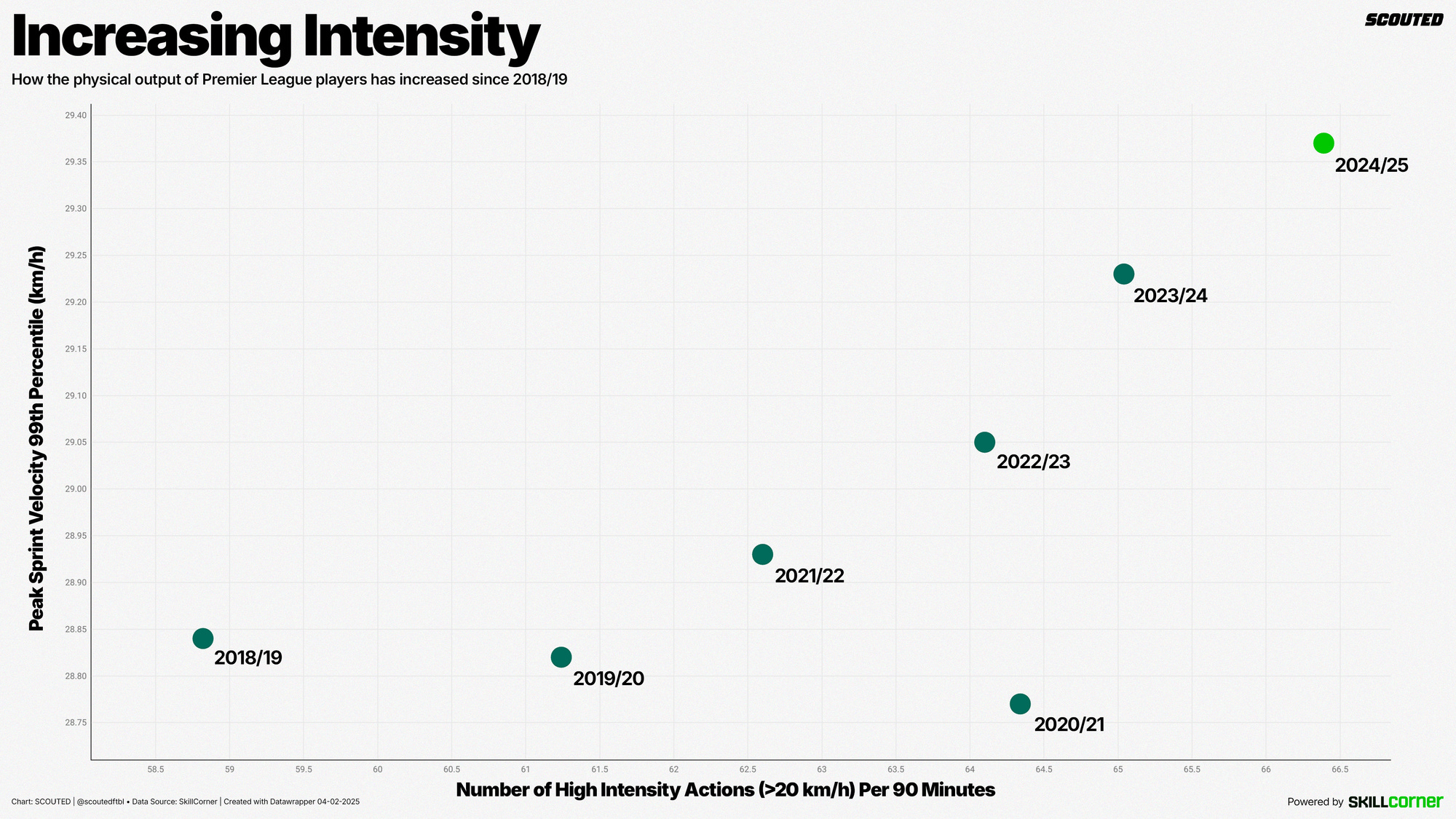

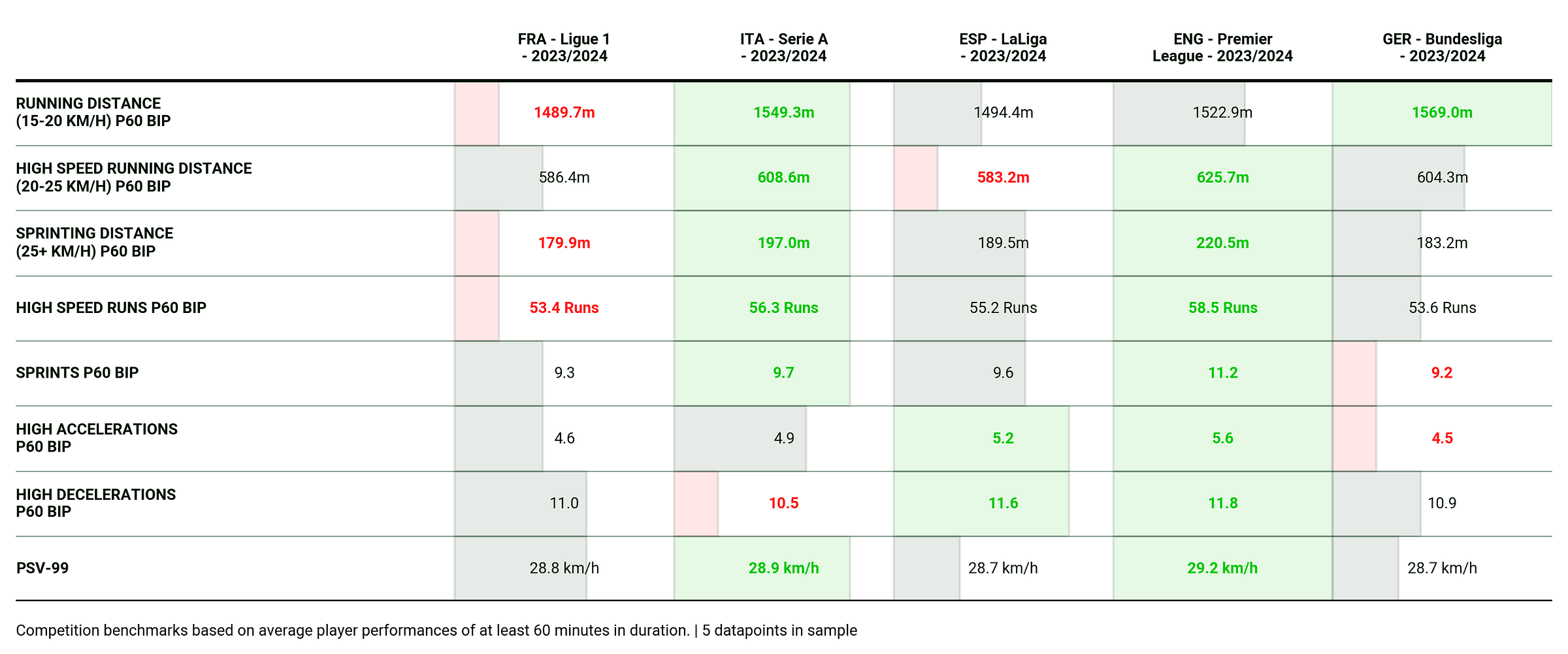

The league is getting more intense every year.

Below, in another great SCOUTED graphic, you can see the levels of difference across the leagues.

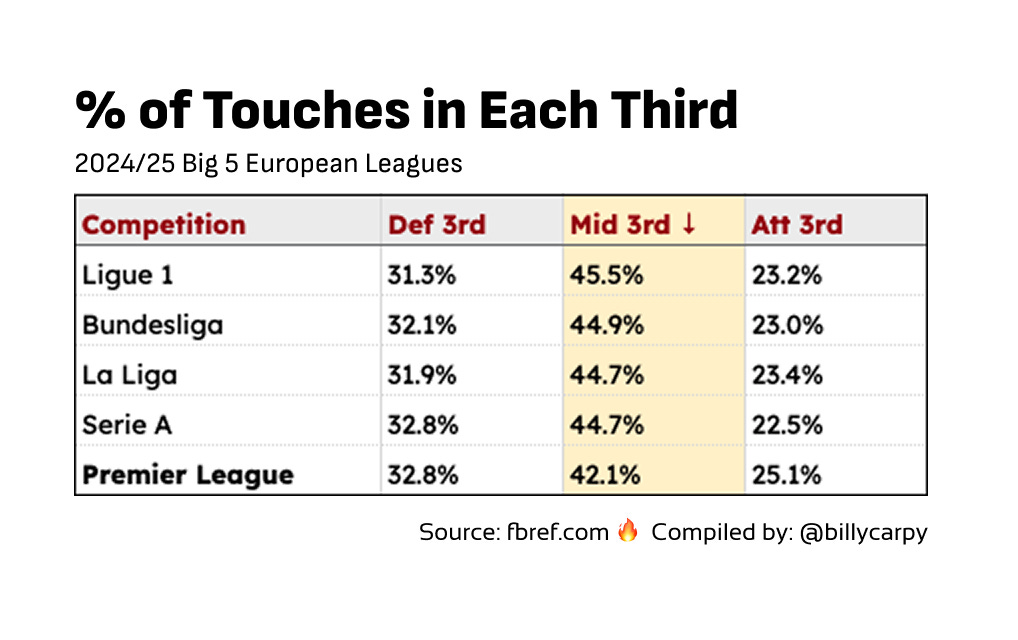

This has created a situation where so much of the play is happening at either end of the pitch. The Premier League now has the lowest percentage of touches in the middle third among Europe’s top five leagues.

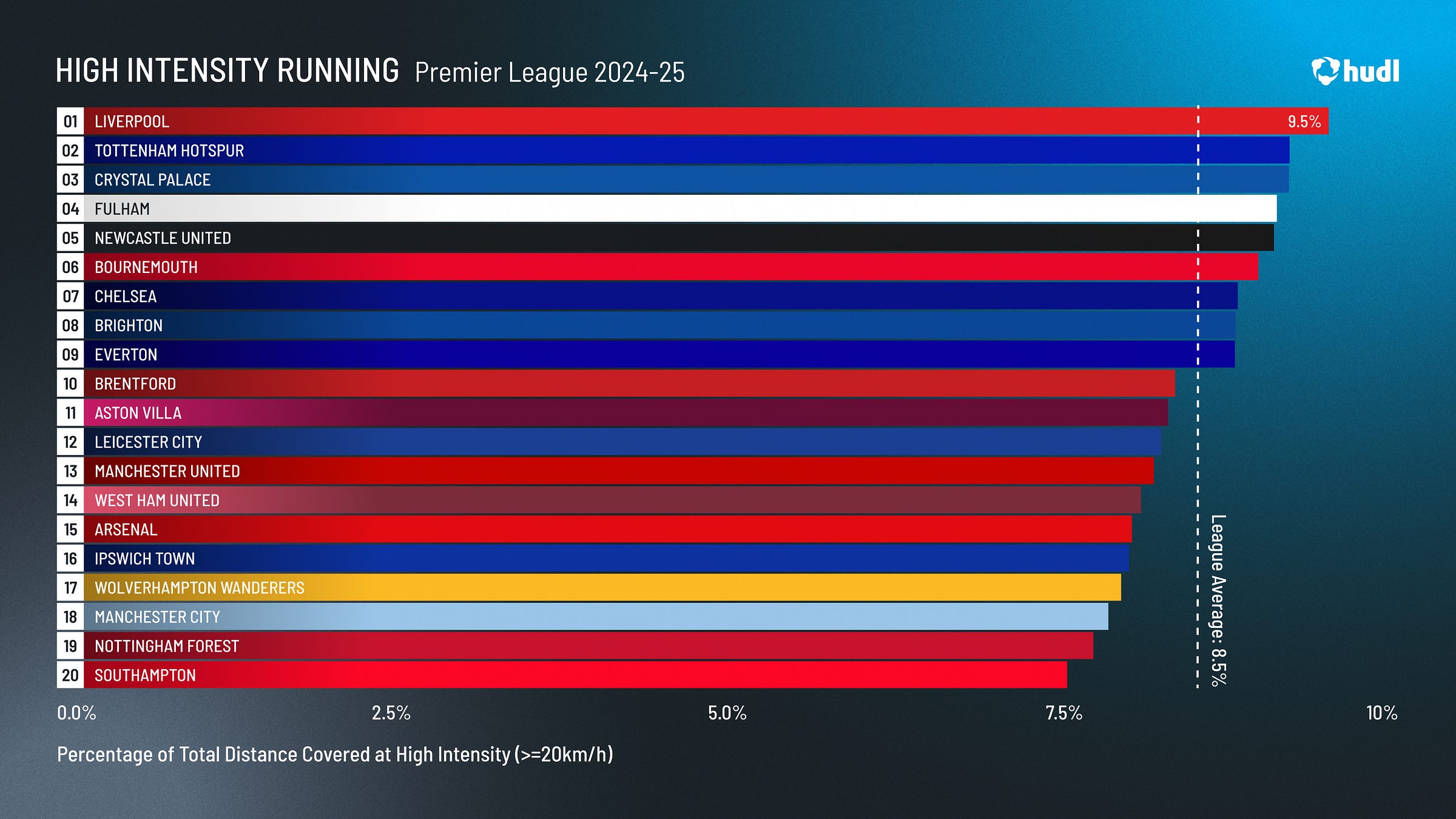

Next, we’ll look at this from an Arsenal perspective. We’ll need to be clear that ‘high-intensity running’ does not automatically equate to ‘good.’ But it’s also clear that Liverpool were the league’s top attacking outfit, and in Kerkez, Frimpong, Wirtz, and Ekitike, they’ve only doubled down on that advantage. Arsenal, who so often turned down the press and dominated possession, ranked just 15th.

…and this is the clear throughline in the window: what do Heinze, Madueke, Gyökeres, and Zubimendi have in common? They all went to press the issue.

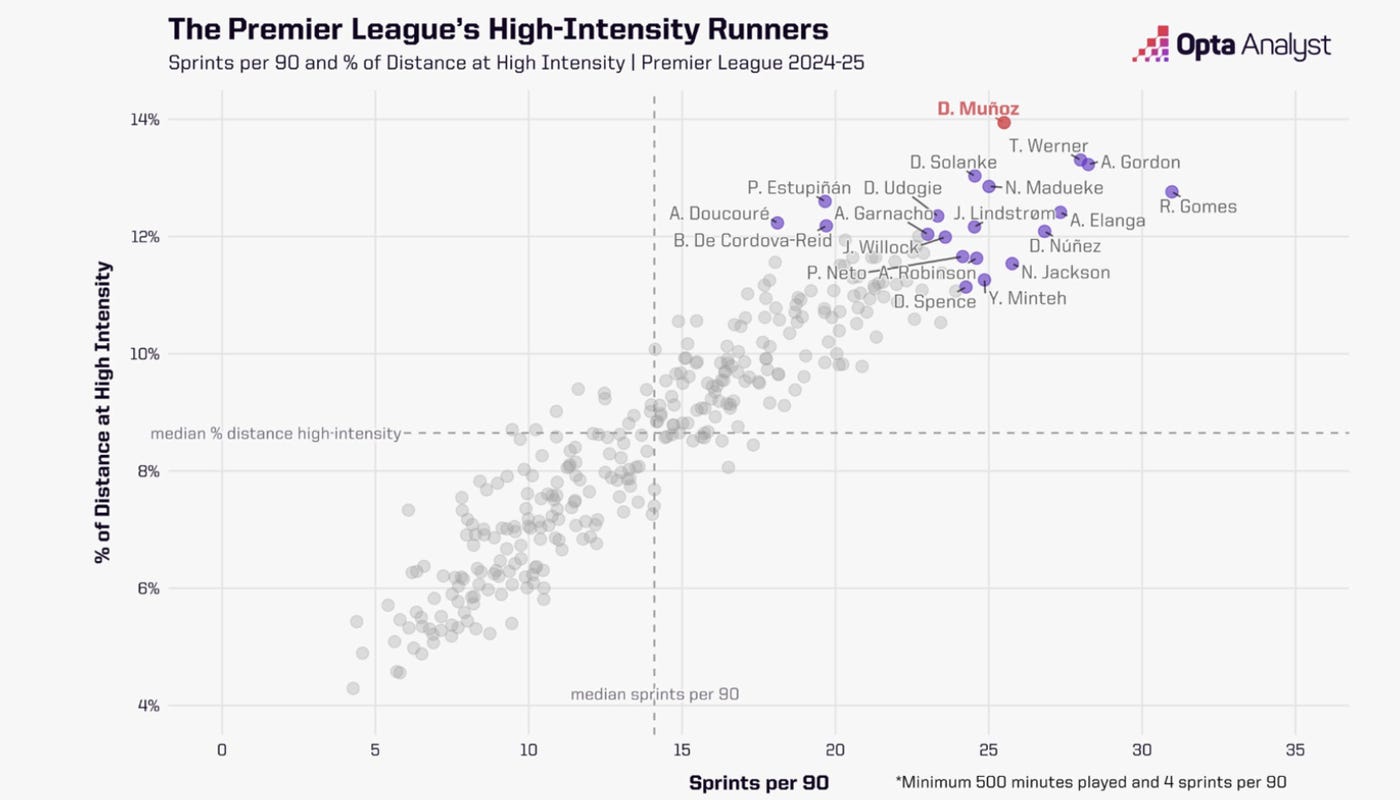

From Opta, you can see that Madueke is at home amongst the league’s top runners:

Here, too, via SCOUTED, you can see how his runs led to shots.

In my striker rankings, we assumed everything was held equal:

This is an “all deals held equal” list — if all players were available at the same price (say, €65m) and looking for “normal high” wages, rather than obscene ones. But more than that, it’s a personal eye test. After generating the shortlist, I watched 1–10 full matches for each player, wrote up notes, ran deeper stats, and adjusted the rankings based on feel.

The rankings were also based on Arsenal-heavy factors, which included two big ones: we have a good striker already, and we face a lot of lower blocks. The final ranks were: Isak, Alvarez, Osimhen, Šeško, Ekitiké, Gyökeres, then others.

We know, of course, that all the deals weren’t equal, and some of those numbers got positively silly. We’ll see what happens with Isak. Šeško and Ekitiké both came in higher than expected; I’m wary of the fit for Šeško, but Ekitiké may just be a stone-cold superstar.

I’m especially questioning of the idea that Arsenal haven’t yet banked a fewer-questions, give-me-the-ball attacker to make the left their own, and to offset the final ball questions elsewhere, but there’s time still, and I actually like Madueke’s qualities on the left plenty.

The Gyökeres fee looked nice and reasonable considering the market. Considering his goal-scoring record, any doubts were basically priced in.

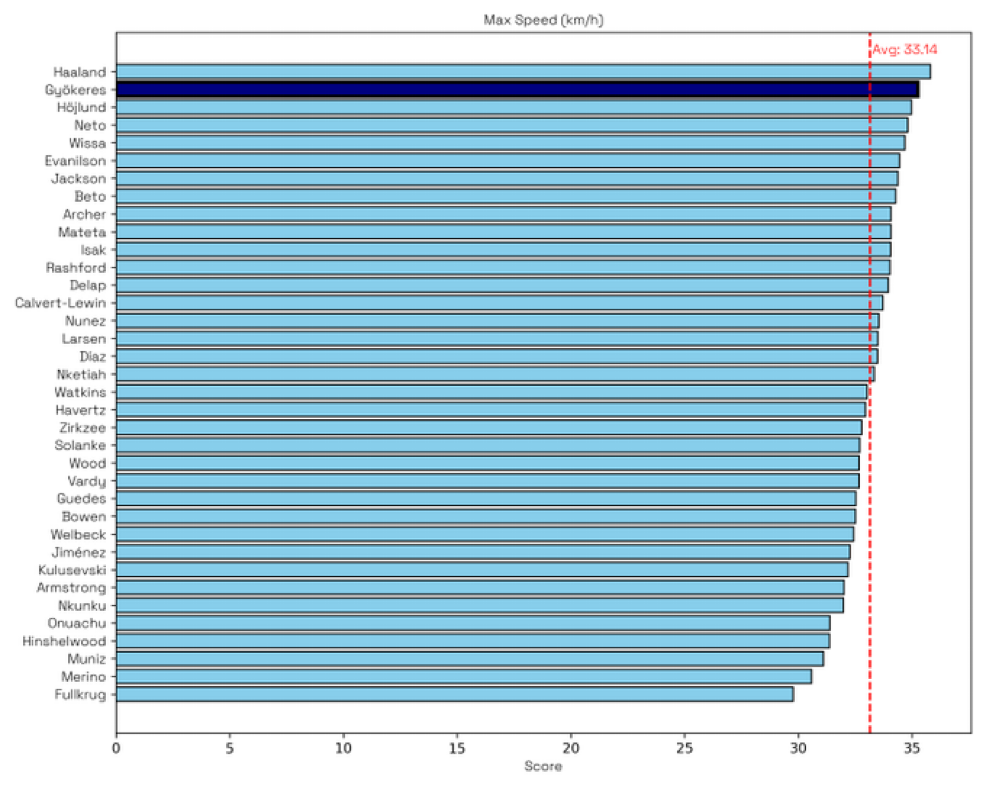

In the research of that piece, the most promising (and new) information was the physical data. Here, through Gradient, you’ll see that his max speed (an average of his top-five games) would place him as the second-fastest striker in the Premier League.

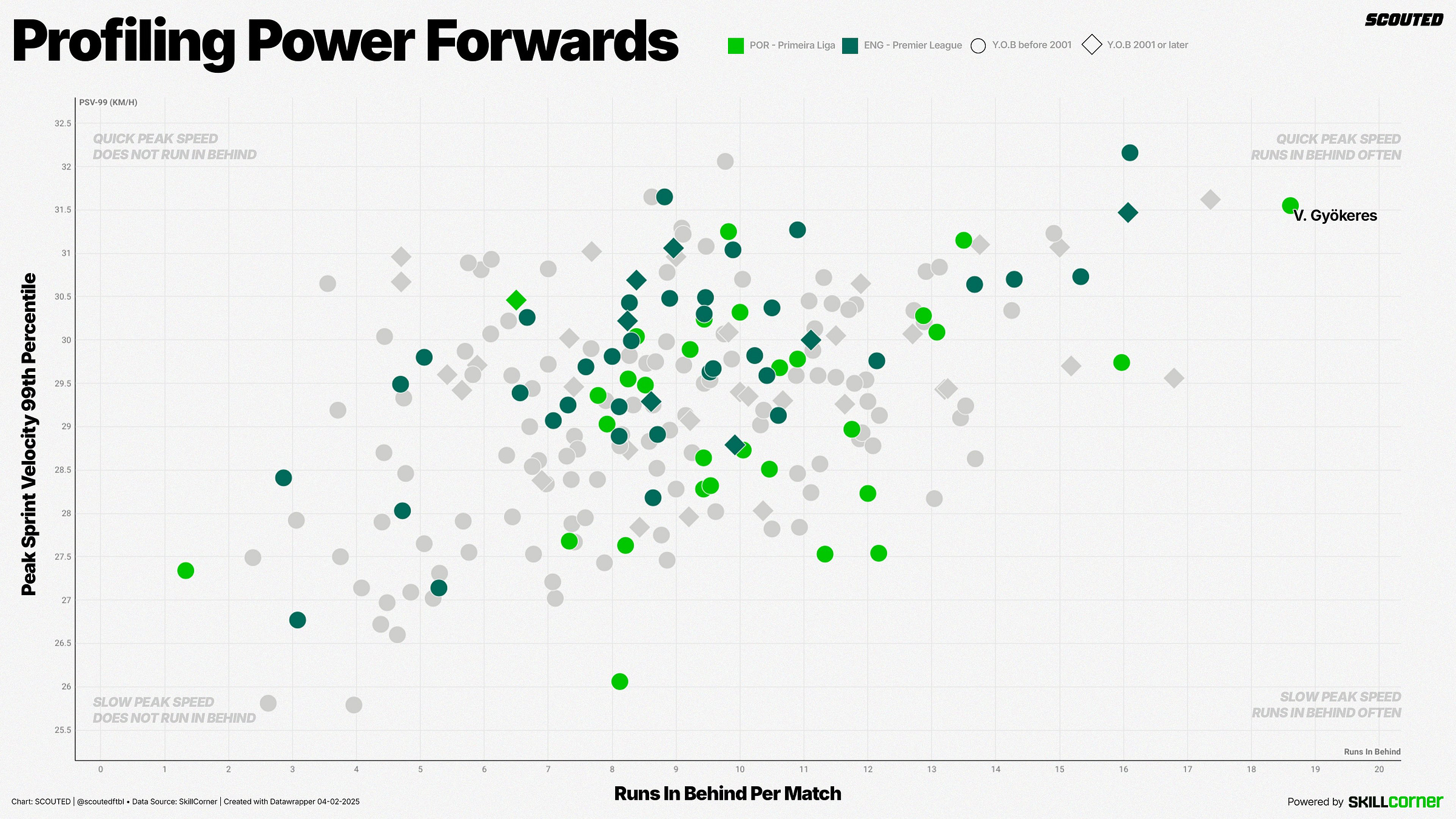

You’ll also see that he made more runs in behind than anyone.

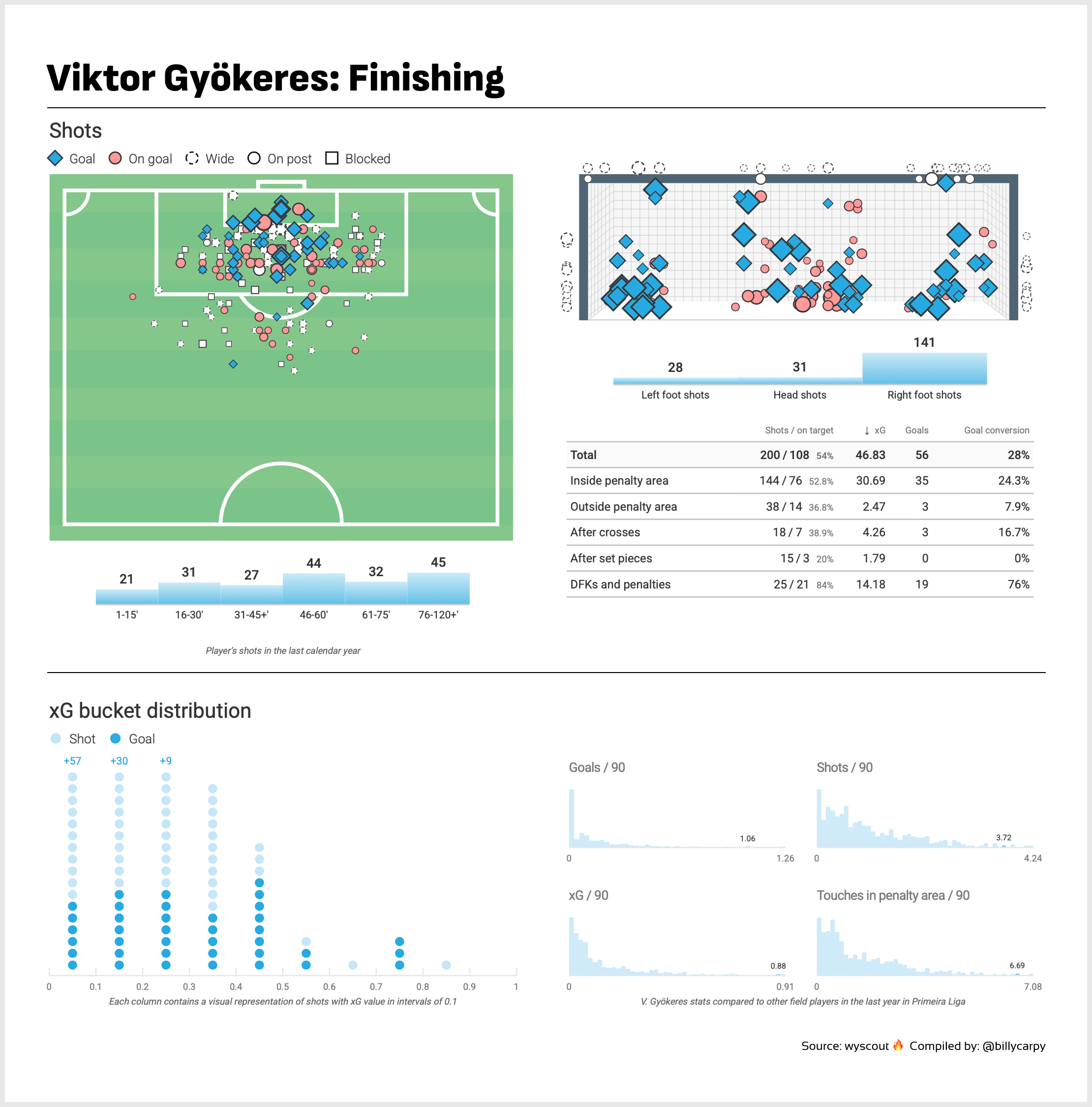

…and here’s the finishing chart.

Madueke quietly shares some of the same characteristics. While he walked a fair amount at Chelsea, he offered no half-measures once he goes: he runs hard and often.

…and the thing that we kept seeing pop up in the film study was how quickly he snapped alive once a ball was won. Here’s him at a dead sprint before the ball is even gathered in the press. He scored here.

For Gyökeres, there’s the endless montage of shoulder runs, yes. But if you’re looking to feel good, here’s the best tonic: a Šeško loss turned into a weak-foot Gyökeres goal in seconds. This is the kind of ball-win-and-delivery that could recreate his best conditions.

How have these new qualities factored in? And has Heinze had an impact?

Well, what we have seen in the statistics is more forward and progressive passing, but that’s a bit difficult to parse. At the risk of wishcasting, I really do feel like we’ve seen the team snap alive and “cheat” on ball-wins more.

The clearest example of that was how aggressively Martinelli and Saka both crept forward on this win, with Ødegaard laying one in there with his right. It’s hard to remember too many times that both wingers were so on top of each other, so greedy and central with a chance.

We also saw that with Swolevertz, who looks every bit ready for the new season, won’t go down without a fight, and will rotate in all types of positions regardless.

But I think the most exciting moments have been these: a sight for sore eyes. Zubimendi and Rice have actually swapped in buildup, and a perfect counter-pressing “net” was cast. Zubimendi drove right at the shape, laid it off to Ødegaard in a tough spot, and the ball was lost. Zubimendi then won it right back. As soon as Gabriel had control, the two new boys were going hard. This is a real, meaningful thing.

You can see another, silly version here. The ball is loose, but as soon as Madueke sees that Gyökeres is going to be the one who claims it, he’s sprinting through the middle. He has an awkward touch and it doesn’t work out.

And that’s the key ingredient of those last two moments: loose balls.

If you have the best defensive structure around, if you have perhaps the best defensive double-pivot around, then you have to embrace what that gets you: the ability to lose the ball, to take risks, and then to press and win it back.

The beautiful Merino arrival goal? The product of a ball loss.

That Zubimendi/Ødegaard left-sided little layoff loss? It immediately led to one of the best chances of the match.

There were two ingredients:

A comfort with losing the ball once the rest shape was set

Immediate runners

There’s a third ingredient that I hope to see us embrace with more clarity: keeping the ball in play, moving, with as many joint touches as possible.

When that doesn’t happen — when play is delayed, when throw-ins and free-kicks take forever, when games devolve into foul-fests — you are increasing the chance of getting “varianced” in the final result. Move it quick and prove your superiority.

To close, I’ll reshare some of my ideas for getting the newbies rolling:

As Zubimendi, Madueke, Gyökeres, and hopefully another attacker join, here are a few things I think should be put into the tactical consideration set for such a carrying, hopefully transitional bunch:

Fewer launches, more playing out the back. I think Zubimendi can help us keep it in the lower third more, and keep it on the ground more, until an advantage is found. I feel like we used the long-ball as

a crutch instead of a weapon last year.

More central combinations, of course.

There’s an opportunity to relax the level of engagement in the first line of press and spring more aggressive midfield traps. This can keep legs fresher up front. But it can also get Zubimendi, Rice, and Ødegaard closer together in the midfield; from that position, you can give them license to be incredibly aggressive about their jumps, winning the ball, and hitting it forward as quickly as possible. Up higher, a combination of Martinelli/Madueke, Havertz/Gyökeres, and Saka (plus, Nwaneri and hopefully a player like Eze) can then save more of their sprints for in-possession phases, and be more likely to receive it in space. This is how you can generate those opportunities for Gyökeres channel runs, not to mention Madueke carries and blindside darts.

Decline “easy progression” more often. There are triggers that cause Arsenal opponents to drop all the way back into the box: wide, fairly uninterrupted carries by Martinelli and Ødegaard, for example. Arsenal should make sure either a) the block is broken with an aggressive pass or b) our most threatening carriers are doing the carrying: Saka, Lewis-Skelly, Madueke, Gyökeres, Rice, Nwaneri, Calafiori, Zubimendi, a player like Eze, etc. If not, recycle and find another way through. I’d like to keep Martinelli more off-ball, more marauding, more associative, more fox-in-the-box.

And a lot of it is just a vibe thing: being more immediate and ruthless when an advantage is on offer.

Arsenal needn’t be fatalistic about not having space. You can generate it.

As an all-in fan of players like Timber and Havertz, I know that everybody is going to rotate and play a lot. But the final element is this: when there’s a tight selection decision between two players this year, as there will be often, I’d really prefer to choose the option who is more likely to result in goals this year.

With such a strong spine, err on the side of risk-taking.

🌆 Cutback city

Arsenal haven’t added a final ball demon, and in Gyökeres, may not have quite as much of a jumping threat (Athletic match notwithstanding). There is an upside to this, however.

On the right, Arsenal have some of the best cutback providers in the game in Saka and White. Last season, you can see how many of Saka’s low crosses didn’t find a recipient, with Havertz rolling out right to cover the lack of a full-back at the time.

Zubimendi and Rice can also help over there.

You can see the quick 1v1 turned into a White overlap and good chance here.

You can also see that unstoppable ability to go both directions from Saka.

If Gyökeres does his job, he should feast on those.

And more interestingly, that may finally be matched by the left. Cutbacks are a distinct strength of both of the new attacking signings: Madueke and Gyökeres.

When Madueke accepts wide, he doesn’t need an overlapper or wide help, which frees a huge channel through the middle for the left-backs (Lewis-Skelly and Calafiori) to have their fun.

When that happens, there’s more opportunity for fun arrival moments like this.

The footage is accumulating for Madueke on the left. Look how little help he has here, and how easy it is for him to get to the byline by messing with timing and then bursting away.

Cutbacks should be a primary source of goals this year. I’ve previously been frustrated with the arrival timings and patterns on these crosses, so here’s to hoping that improves. Rice, Gyøkeres, Havertz, Merino, and Ødegaard should have plenty of chances to clean up when arriving late.

🔥 Other, scattered thoughts

It’s silly how much more I’d like to talk through, but I’ll save it for another time. It’s time I hit the orange-ish publish button.

Some things I’d like to explore in future editions:

I still feel the team is short a swashbuckling, block-breaking, driving, final-ball-delivering creative threat, likely meaning a clearer starter on the left, which felt like a given this window. The spectre of overreliance on Saka and a firing Ødegaard is still there, and the team did look stagnant for periods this preseason. We may be light on truly decisive passing again. There is, unfortunately, already a dependence on Zubimendi’s unique features. Let’s see if that’s remedied.

Jon has a good video out about Arsenal’s pressing mechanics. I think a good, and obvious, reason for additional depth is to be able to throw waves of pressers on against opponents and maintain intensity for 90 minutes. I don’t really think the press was turned down for tactical reasons last year, but physical ones: there just weren’t many healthy players Arteta could trust. One of the first things to look at is how much we go man-to-man early at Old Trafford.

There are a lot of interesting “pods” of complementary players. Madueke opens a left channel for all the left-backs; a nice thing about him is that he automatically makes Timber a usable attacking option at LB, as he clears so much of that space in the middle for him. Calafiori is pod-proof, but may be the best choice for Martinelli and Trossard, as he’s more comfortable outside.

The other interesting pairing is Gyökeres and Merino: Merino can hit the channel ball that Gyökeres craves, and he’s been great at turning late arrivals into simple finishes.

If I were to write an article on one player right now, it’d be Calafiori, who feels pivotal to the year ahead. I’ve talked about how this phase is about “stacking unicorns” in attack, and question whether we’ve done it sufficiently. Oddly enough, Calafiori is one.

The new attacking signings have the out-of-possession desire, but I did notice small moments of ‘feeling out’ the communication and jump timings with both of them. We’ll see how that progresses, but that could prove decisive in Arteta’s lineup decisions in the meantime. (I’d personally consider Madueke as a LW starter at the moment, and would be leaning Gyökeres’ way as he regains fitness. I expect Arteta to have easing-in periods for both, where they earn their time. I’m less complicated these days: I want goaaals.)

Running is complex. Gyökeres is, by any measure I’ve seen, faster at a dead sprint than Havertz, but I think Havertz is a much quicker and more effective presser (which could be related to whether they are straight runs or curved runs). Another interesting topic between the two is who looks best as a late-game sub. Havertz is great with leads, as he’s transitional and can help clean up on potential set pieces (I hate the idea of surrendering late set-piece goals). But Gyökeres can really get to running against tired legs once the game gets more end-to-end, and he historically racks up goals as games progress. It’ll be interesting to watch.

Love the Kepa signing personally. We like to think we had a worst-case injury thing last year, but Raya was a single point of failure. That’s no longer really the case.

Will write about Dowman and Mosquera soon, I promise.

This team is good enough to win the league as-is. Any number of variables will pop up before the end. We’ll see.

So where does that leave us? Arsenal stand on the edge of another season with more pieces, more depth, more conviction. The only tension, as fans, is that we know too much.

But maybe that’s exactly the challenge now: to hold this team as it is, not as a reflection of past events, but as something alive in front of us. To see the possibilities without rehearsing the alternatives. To keep faith that the story is being written in the present tense.

“Can I take another year?

Must I be so damn severe?

From the valley to the pier,

I'm beset with what we could become.”

— Bon Iver, “From”

There isn’t a better football writer than Billy right now and I’m glad he writes about Arsenal.

I’m nervous about this start. If we lose against United after all the big teams won this weekend, it’s gonna start all the negative fans who want to complain. I’m still scarred from how many things went against us last year and praying the refs/injuries/red cards/variance don’t kill us again.

A big win tomorrow against an improved but defensively weak United would assuage a lot of my fears.

Fantastic post, mate 👏 Excited to see how it plays out.

I am already in love with the Zubimendi-Rice combination in midfield, and I keep thinking about the 4-box-2 shape you've posted before; I cannot escape the idea that a Zubimendi, Rice, Ødegaard, Havertz box feels like the most 'Arteta' system possible, but then raises the question of how Gyökeres fits in.