Anatomy of a goal-kick

What the Ramsdale launch that led to Trossard's first goal can teach us about how he and Arteta approach distribution

There are a million things to talk about after the game against Barcelona, but I’ve met my long-read quota for the week, so I’m going to talk about a single goal-kick. Naturally.

Aaron Ramsdale’s dad does not like it when he plays out the back:

"He still hates it, absolutely hates it," said Ramsdale. "Still threatens to text Mikel. The only problem is if I push it too far saying 'go on then, you won't do it,' he actually will because he's got his number! I've got to play that one really carefully.”

Banter aside, Ramsdale does a lot of different things with the ball — not all of them sharp this preseason, certainly — and he may leave you wondering how he makes the decision to play out the back or go long. Today, let’s talk a little about the strategy rather than the performance.

Arsenal are a bit of an outlier to their top-of-the-table brethren, who usually default to playing it short. Ramsdale takes a wider, more pragmatic approach:

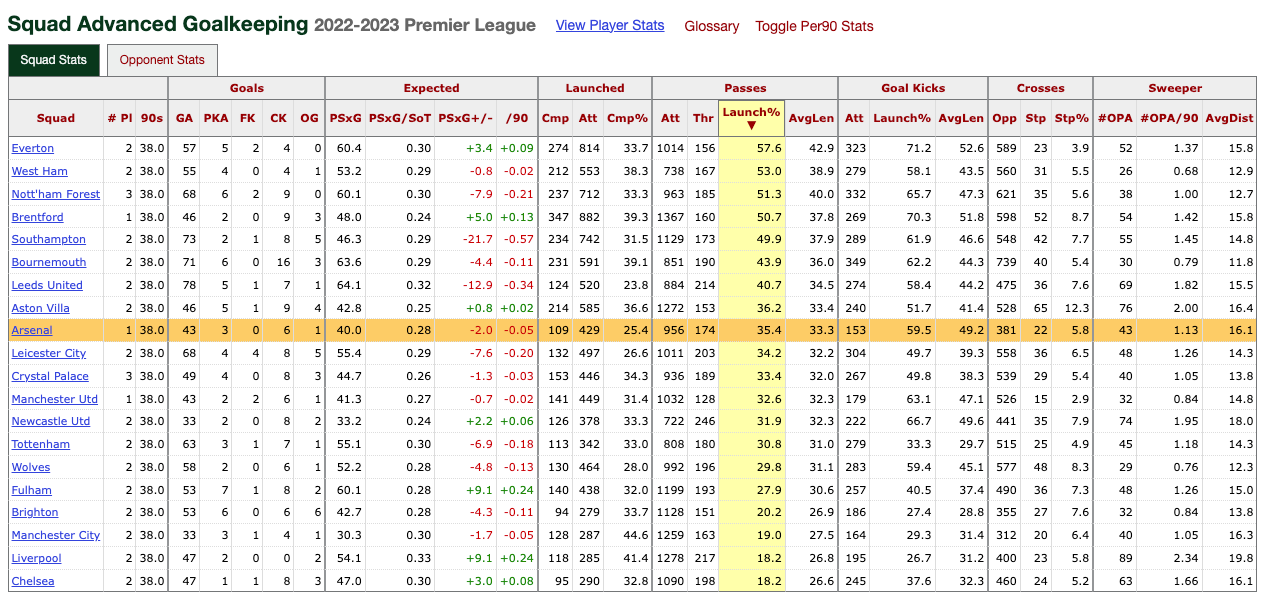

When looking at his launch percentage — which is defined as a pass that goes further than 40 yards — he is right in the middle (54th percentile):

The strategy varies greatly from game to game. There were six contests in which he launched more than half the time, and they were all against quality competition: Liverpool (2x), Brighton, Tottenham, Sporting CP, and Newcastle. On the other end, there were six games when he launched it under 20% of the time, and those were all against cellar dwellers: Nottingham Forest twice, Bournemouth, Wolves, Everton, and West Ham. The short version is that if they’re facing a bus, they’d like to get it out of its parking spot.

It is, then, a pretty pragmatic determination — though, interestingly, they looked to play it out the back a bit against Manchester City. How do they make this call?

There are a lot of factors in play. The first factor is just the intention determined in prep. This intention is not always tactical: for instance, I reckon that Ramsdale goes long on kickoff routines because Arteta wants to set the tone of crashing into the opponent and fighting for a second ball immediately.

Next, it’s qualitative: if there is an individual matchup to exploit, exploit it.

And finally, it’s numerical. One of the shortcuts a keeper can use is just by looking at the back-line. As Roberto De Zerbi explains here, if there are three backline defenders on two attackers up top, for example, you know you’ll outnumber them by two players in build-up (if you include the keeper).

Against Barcelona, they went long against a team that surrendered only 20 goals in 38 league games last year. Rather than playing through the press, Barcelona’s stretched back-three could offer more opportunities for joy, which helped spark a performance that felt pretty dominant even if Wyscout lists Barcelona as winning the possession battle 58%-42%. Here was Ramsdale’s distribution:

But you still want to have numbers, which brings us to the moment we’ll look at.

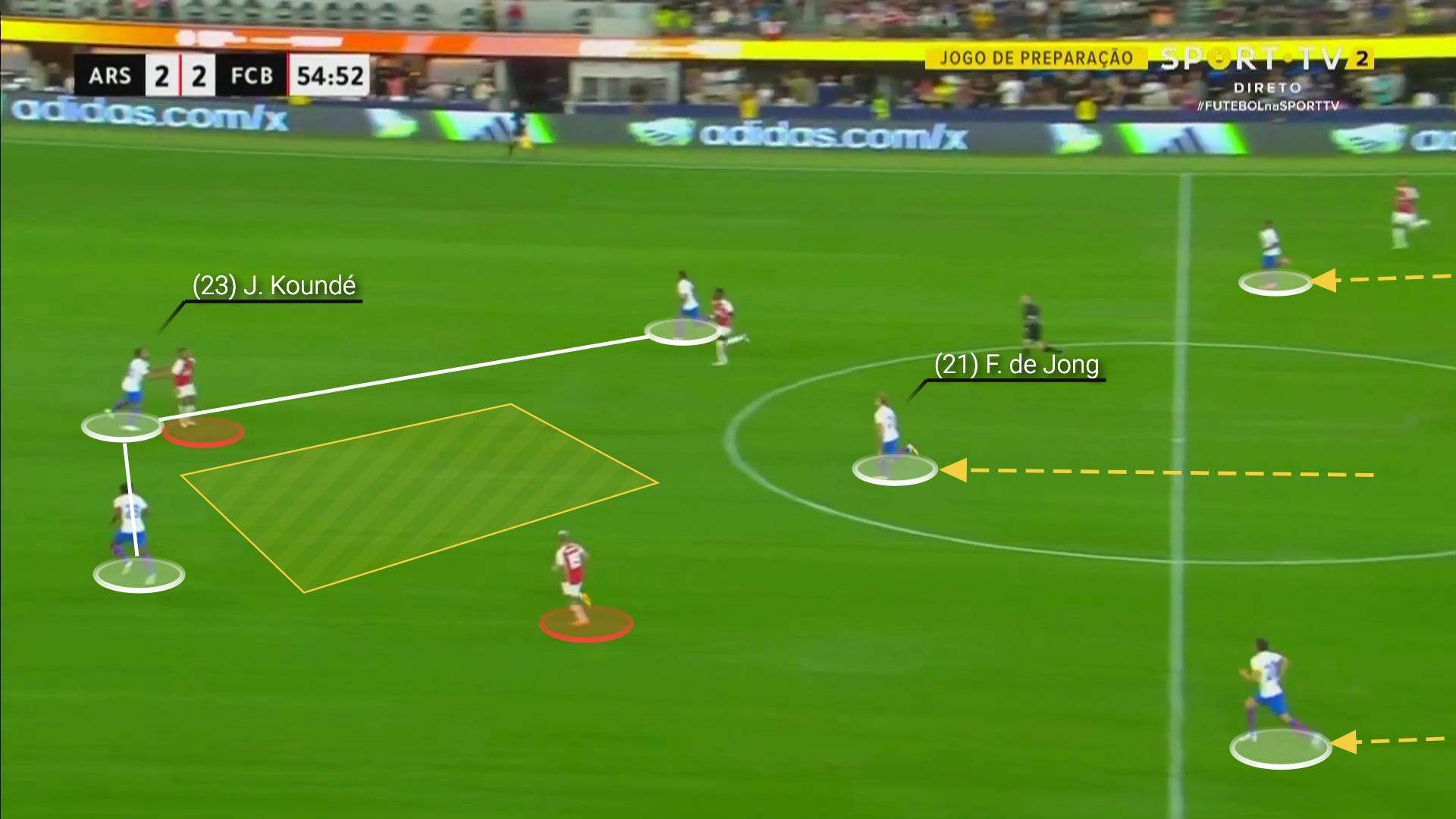

Here, Ramsdale had been going long all game, and Barcelona stayed back to add support. The numbers were not on Arsenal’s side — out of picture, it’s a 5v6 in Barcelona’s court, with attackers man-marked and de Jong patrolling the middle, helping out.

Though Arsenal can still kick it deep into those situations, with a “U” of attackers forming a circumference around Jesus, it can have low odds when expecting somebody like Trossard to emerge from the dogpile.

So below, in unison, you’ll see five players gesturing for the midfielders to come back down, even though they would already have numbers in build-up:

Ødegaard and ESR then drop to bait their defenders down. Because Arsenal are also great at doing this kind of build-up play, the defenders have to show this move some respect. By the time Ramsdale kicks it, their markers — Kessié and Roberto — are brought into the picture. But that’s not the only thing that happened:

The human numerical advantage in back — de Jong, in this case — also got dragged forward.

And voilà, now you have Jesus backing down a not-huge CB in Jules Koundé — he’s so brilliant at this, isn’t he? — and you have stretched man-to-man markings elsewhere, plus Trossard with a huge, uncompetitive area of space with which to gather a second ball:

This is how that bouncing ball played out in gif form:

…and even though Barcelona have players coming back, they are a little unsettled, and Trossard pounces for a far-post goal:

Arsenal, 3-2.

Because Koundé got his head on the initial ball, I believe this one goes down as an incomplete pass for Ramsdale, by the way. It’s a handy reminder not to over-index a stat like pass completion without a whole heaping of context. Take it from a 72.7% passer by the name of Kevin De Bruyne: “I don’t care about pass completion. That’s not what I am here for. I am here to do what I am good at.”

Long-balls have their place, so long as they are strategic, and not clearances by another name. They have the knock-on effect of making Ramsdale’s dad happy.

By showing the ability to play out the back or go long, and through the additions of first- and second-ball experts like Kai Havertz and Declan Rice, Arsenal offers another form of unpredictability to their repertoire, one that their top rivals don’t use quite as much. Whether in the normal shape, or an occasional 4-2-4, it will probably prove useful in the Champions League.

OK, I’ll be disciplined and end there. More to come in the days to follow.

Hope you’re well.

❤️

excellent point on completion %age not meaning much. Arsenal thrive on the second ball, which generally never shows up in surface level stats

Great read as per usual.