Back in action

Arsenal return after a much-needed week away. Here’s a huge shakedown on luck, tactical learnings, finishing, the power of complementary profiles, and the quest to rack up results when it matters most

“Depend on the rabbit’s foot if you will, but remember it didn’t work for the rabbit.”

– R.E. Shay

Jürgen Klopp knows something about luck and variance.

Stop me if you’ve heard this before. In 2015, when he was in his third week at Liverpool, it was time to meet Dr. Ian Graham, the team’s director of research, who was hoping to convince the new manager of the value of data. Looking to convert a new disciple to the all-seeing, all-knowing ruler — the Almighty Abacus — Graham unspooled his archive about Klopp’s previous season at Dortmund.

It made for a fascinating study. The team’s seventh-place finish in the Bundesliga didn’t even properly capture the depths of that campaign; they were a rock-bottom-18th all the way until February. The media were wondering if he’d fallen off, and given the table, they were not fully without reason.

By April, Klopp would announce that it was time to move on.

Had he fallen off, though?

Graham’s answer, as it was presented to Klopp, was an emphatic no. According to the reformed academic’s models, Klopp had just managed the second-unluckiest side in the league in ten years.

As it turns out, Graham had been involved in the team’s managerial search, and this was the very data they used, at least in part, to land on the grinning German for their vacancy — though the data points of “league title” and “Champions League runners-up” didn’t hurt. To say this decision has worked out would be an understatement.

Klopp was convinced by the report, just as we all may be when some PhD prepares a lecture about how They’re All Wrong and Actually You’re as Great As Ever. The rest of the stories are legion. Using a similar model, Liverpool would go on to sign all manner of players, some of whom had been undervalued, unlucky, or misunderstood. These reports helped the club train their gaze on Mohamed Salah, despite some misgivings from Klopp himself. Together, they would win everything there is to win.

But in the years to come, conversations like these would become more commonplace, and resistance would wane. I would posit that this all shows something a little bit more nuanced about variance and luck in this sport.

👉 A junior analyst

My youngest son has a weird quirk. After a match like the one against West Ham, he’ll retire to his room, bitterly disappointed, insisting we “lost.” To show him how that isn’t true, I’ll print out the xG charts and field-tilt graphs and slide them under his door. He’ll persist with some naïve bullshit about the other team scoring more goals or something. Eventually, I hear the door lock. I’m not sure he even reads my charts.

Oh well, he’s never been the bright one.

In all seriousness, as much as I hope to put my belief in statistics on full display for you in these pages, I love the game way more than I like the numbers, and I love the human element most of all.

Especially once they accrue significance over a longer period, numbers can help us preserve our clear thinking in a sport that often deprives us of it; they can help us understand real trends in performance in a sport awash in emotion, nonsense, and conjecture; they can help us make better decisions when luck and variance win the day, and they often do.

But I also don’t cede to the pressure of speed-running the highs and lows of fandom, and, like the old man at the pub — or my (real) son in that (fake) story — I find your (i.e., my) newfangled charts to be thin comfort in the moment. In fact, I think it might be more infuriating to know the extent to which Arsenal had better numbers than so-and-so but still lost; I also don’t think “more possession” or “more shots” necessarily means “better” or “more in control,” especially if the other team is choosing to allow such things.

I probably put it better here.

So as much as I believe in accounting for all the xG/variance/luck/randomness of it all — which I do; I’ll continue to write about it every week — I also try to find a balance with the forbidden deal we all make with this game: put it in the goal, or deal with the consequences.

Relatedly, here’s how Sidney Lumet described the process of making a movie.

“It’s a complex technical and emotional process. It’s art. It’s commerce. It’s heartbreaking and it’s fun. It’s a great way to live.”

Football is some bullshit. I love it all the same.

I’ll use Klopp to illustrate my point. Everybody — from the media to Klopp himself — would have been well-served to lean on the numbers to reinforce how the results of his last season at Dortmund weren’t really indicative of Klopp’s basic abilities as a manager. But amidst a run like that, I also fault no one for being deeply disappointed with their tumble in the table, or for desperately searching for ways to reverse the team’s fortunes while it’s happening.

Likewise, luck and variance have greatly informed Klopp’s time in the Premier League. Facing a petrostate behemoth, you don’t win the title based on a few plucky, intelligent signings. You do it by doing that, plus expert managing, plus near-perfect performances, plus a healthy squad, plus variance and luck shining a warm light upon you. The margin is just too narrow otherwise.

As we covered last time in What Ails Arsenal, the conversation around xG can be conflated into one about luck, but it also includes a host of other factors like composure, finishing quality, quantity and quality of chances, timing, variance, goal-keeping, fatigue, statistical error and bias and noise, and so on. José Mourinho was just sacked after 2.5 years of “not catching a break” on xG. Graham Potter’s Brighton teams seemed to have some reliable issues in this regard.

With all that in mind, here are the performances relative to xG of the last six Premier League winners, according to Opta.

22/23: +11.9

21/22: +7.6

20/21: +15.8

19/20: +13.0 (Liverpool Premier League title)

18/19: +6.7

17/18: +24.3

Arsenal led the league in how many goals they scored over their expected total (at +11.9, even with Manchester City), bouyed by Martinelli (+5.7), Ødegaard (+5.0), and Saka (-2.9). This year, they are at -1.9, and there are no notable overachievers.

In Liverpool’s title year, they had a host of factors working for them. It seemed like every member of their squad — Salah, Mané, van Dijk, Firmino, Alisson, and so many others — was in that sweet spot of 25-to-28 years old, experienced but spry. Trent contributed 13 assists as a 20-year-old. The injury bug was largely kind. And yes, they overperformed their xG at the highest rate in the league.

Klopp has experienced the top and bottom of the ladder, and every rung in between. (He’s even been relegated from the ladder!) Are good fortune and individual “overperformance” fleeting? Sure. But teams can have their input — they can manufacture at least some of their own luck — and these concepts are also fairly necessary to win a Premier League title in this era. It’s understandable to feel morose when they’ve left your club for a spell.

The Variance Monster comes for us all, but the objective is to build something that can transcend the unfortunate bounces with more regularity. Arteta is on a mission to do that through control, physicality, and perhaps a little bit of energy management. In truth, fortune wasn’t unkind for the first few months of the season, but unfortunately, the attacking fluidity only returned just as luck and finishing quality left the building. The shots started falling wayward while opponents nailed every half-chance.

To investigate, I pulled the shooting numbers since December, including the FA Cup tie. According to Wyscout (which differs a little from Opta reporting):

Arsenal have scored 10 goals on 144 shots (6.9% conversion).

For comparison, the 16.04 shots per 90 would be first in the league; the conversion rate would be 19th.

Opponents have scored 12 goals on 69 shots (17.3% conversion).

The 7.68 shots per 90 would be 19th in the league; the conversion rate would be first.

It makes for an annoying thing to write about. It’s either incredibly complex (nuanced factors about box arrivals, passing dynamics, shooting fundamentals, set piece defending) or incredibly simple (the luck is bad and will return). Likely, it’s a combination of the two.

The next, next step? Fewer mistakes, a little more experience, a little more squad depth, and some more cold-blooded finishing edge. This all is not totally there yet, but it is damn close; the final bit is difficult to achieve, and no given. But our Arsenal need no incomings to be very, very good in the meantime. We would certainly not be the first team to weather a fallow period and go on to win Big Things.

Given all this talk of Klopp, it was fitting, then, to have so much of this play out against his Liverpool.

👉 (Don’t) stop the presses

While I loved the energy and determination brought by the players, I had a few rankles after Anfield.

I had no issues with Arteta seeking to best them on the dribble, as Liverpool can be lungy in the duel, which opens up lanes at some of the higher rates in the Premier League. Their players just stepped up on the day. For that, you tip your cap.

My central problem was with the overall stance of a rested team against an opponent who had played in the Carabao a few days earlier. The game plan featured a compact, disciplined block — springing into über-direct counter-attacks that never came off, turning the flow into one that suited the opponent. Writing then:

I felt Arteta made a couple (relatively marginal) tactical missteps.

For one, Arsenal had just shown Brighton that it could mount the most disciplined press imaginable, and, risks and all, I would have loved to have seen it turned to 11 against Liverpool, who can play a little loose, and were coming off a quick turnaround (whereas Arsenal got a week to rest and prepare). Scary to do at Anfield? Sure. But we have Declan Rice.

For another, Arteta had previously made aggressive affordances to compensate for the presences of Salah and Alexander-Arnold; he didn’t do that here.

In all, I felt it was a question of identity, and the tactical makeup of the game turned it into one based on transitional moments and individual brilliance, instead of relentless pinning and suffocation. That naturally tilts it into the balance of Liverpool.

In the FA Cup, a few absences and selection choices would have a major impact on the proceedings. Salah and van Dijk were unavailable, and meanwhile, there were a few interesting selections from Arteta, including Kiwior at left-back, Jorginho in the midfield, Nelson at left-wing, and Havertz up top. We’ll cover that all in a moment.

You’ll see the difference come through in the numbers.

Arsenal successfully made it an Arsenal game. They had 50+ more passes, fewer forward passes, more backward/lateral passes, and fewer bouncing balls in general.

It all started up front. We got the full-beans press we were looking for.

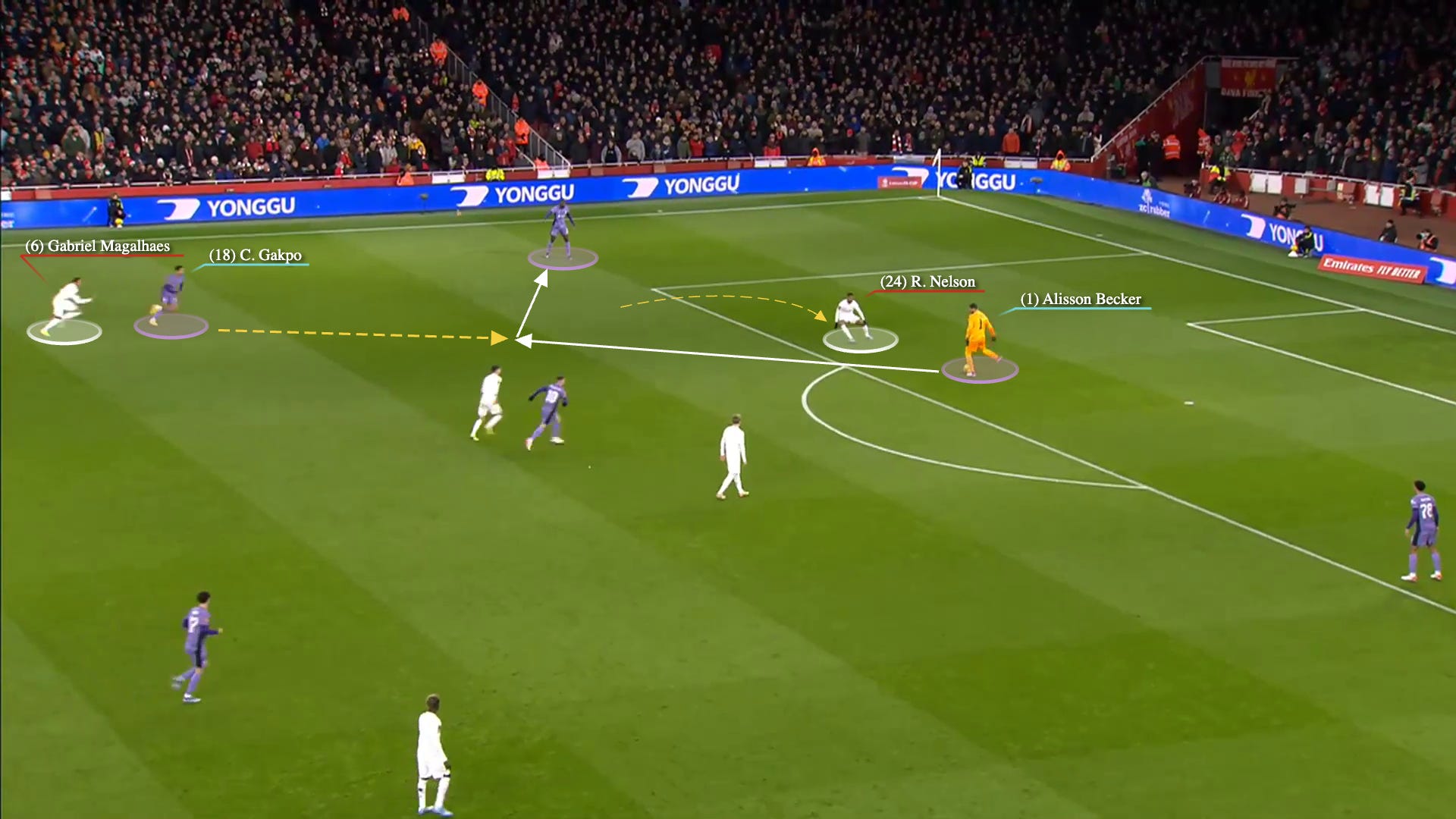

Liverpool started in a 3-2 shape with Mac Allister and Alexander-Arnold forming a double-pivot. Havertz had a few iterations of his pressing role, but here, he did what we were crying out for — “cover shadowing” Alexander-Arnold to deny the ball to him. In a theme, you’ll see Jorginho calling out the assignments with Rice tucking in behind, defending the big space. On the other side, Gomez looks to exploit Saka’s “hybrid” responsibilities by trying to sneak behind him.

With Havertz following Alexander-Arnold around, Liverpool sought to do what a lot of teams do against such a man-marking scheme: drag the players around to their liking. Trent left the picture and Gakpo dropped deep, which would pull a CB (Gabriel) all the way down to the edge of the box.

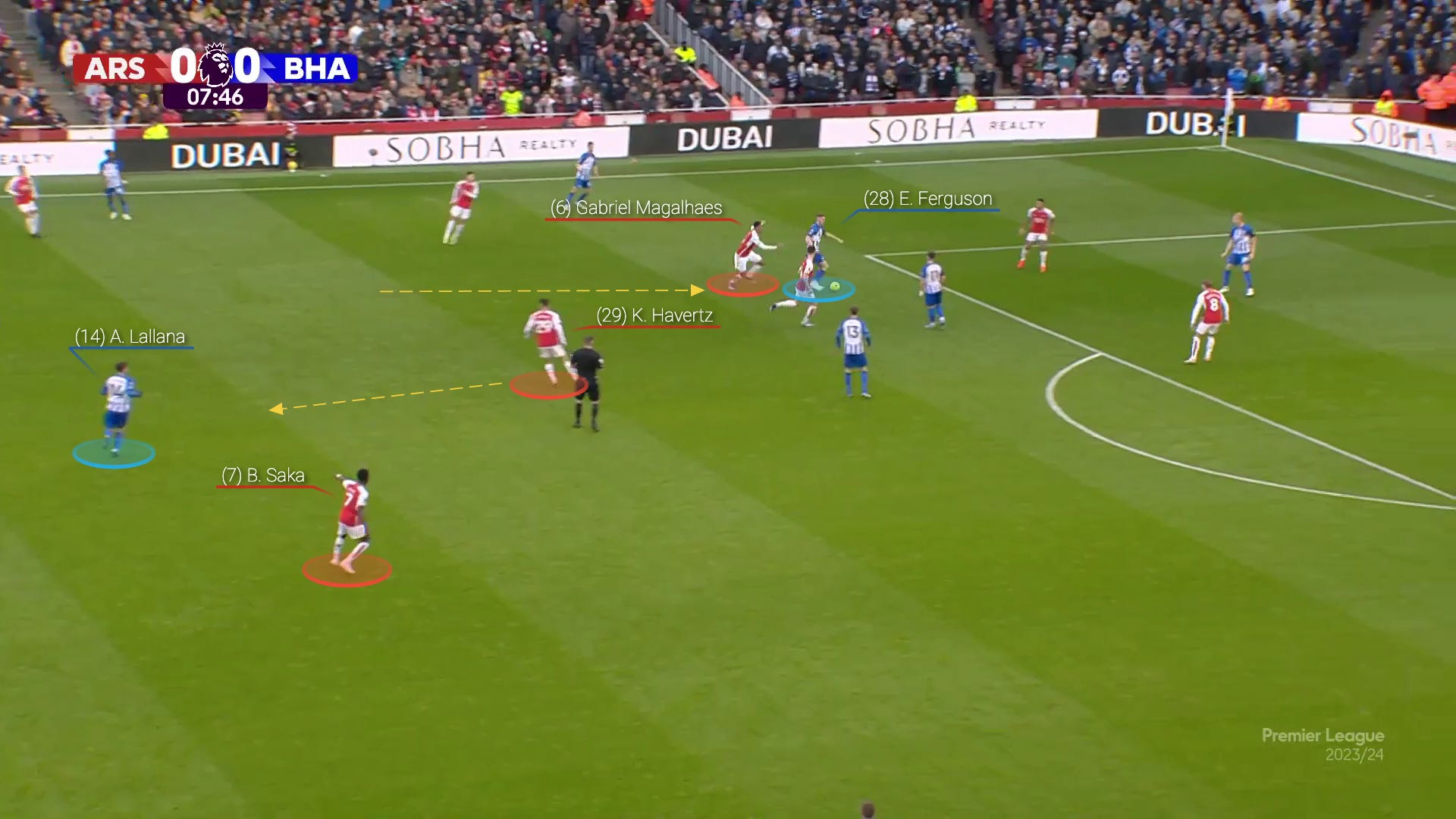

This was very similar to what Brighton were trying to do with Ferguson. Remember this?

But, like against Brighton, there was excellent coverage and rotations. If you watch Manchester United, this is exactly the moment they break: there is a pass, one player gets dragged, and the coverage either fails to show up or does so late.

Similarly, it’s logical to accuse a Gabriel of being “dragged out of position” in a situation like this — you’ll hear that kind of thing thrown around when somebody like Zinchenko follows his man. Without doing it, and the lock-step rotations and backups that follow, you don’t really have a man-oriented press.

Here, Nelson and Jorginho both know their role, and it is recycled back to Alisson. With so many players pulled around the Arsenal left, the keeper envisions an underloaded Arsenal right.

But Saka had sniffed it out, and dropped all the way back with Gomez. He intercepts and kicks it forward.

But the play is not over from there. Quansah gathers it, and Havertz does a curled run from the 9 to box him in and deny his access to Alisson and Konaté. Jorginho is barking directions again as things are a little jumbled, and Curtis Jones is going to drop down to the left-back spot to support his centre-back. Saka follows him instead of Gomez.

…and here is the highlight to seal it. Jorginho sees that Quansah will have to play it long before the centre-back even does, so he shades back and directs traffic. Saliba steps up to win possession, Jorginho is right there, they do a quick rondo, and Jorginho turns to break the line.

It’s all pretty relentless and highly satisfying to watch.

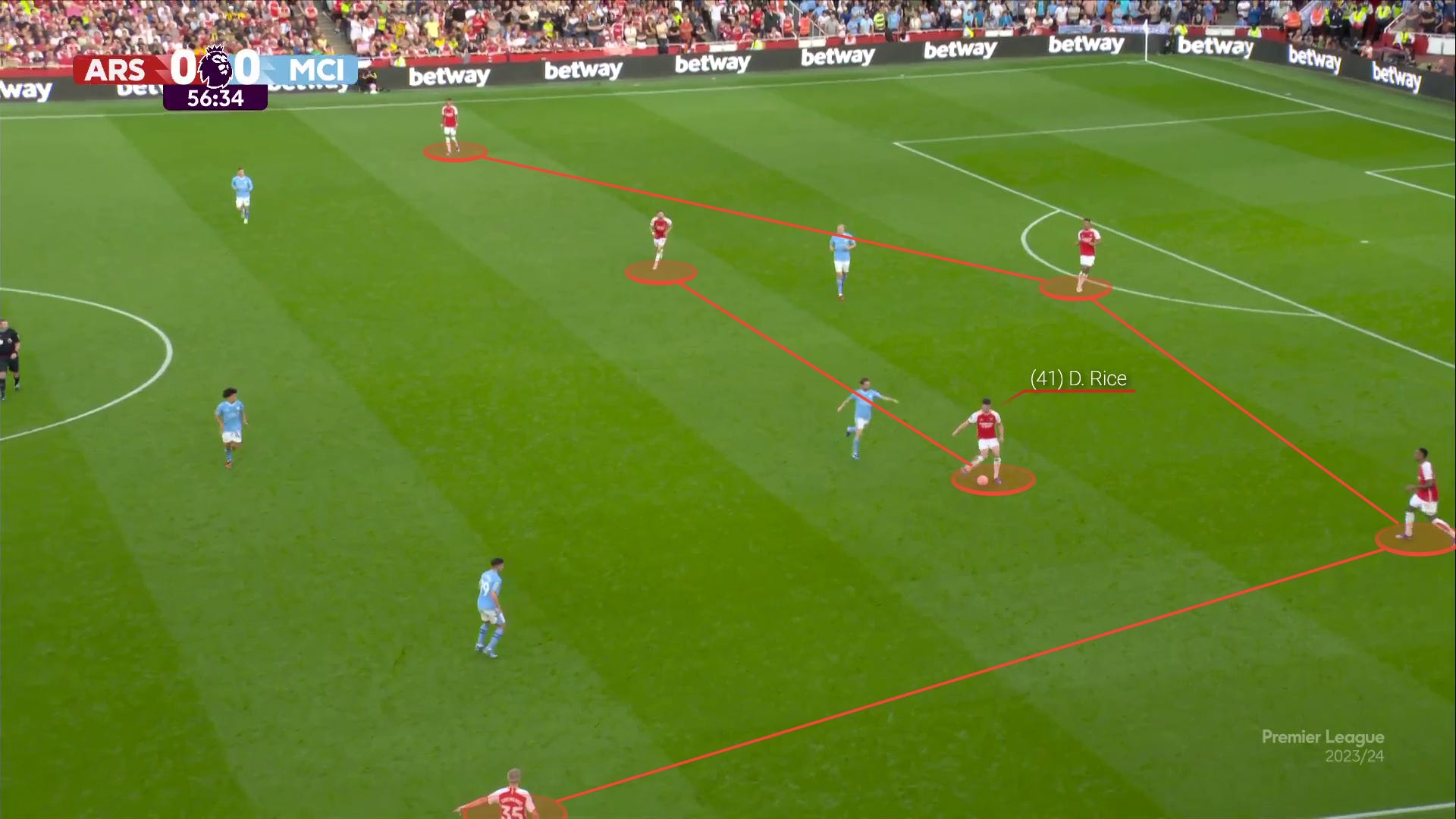

Later, you’ll see a clip that is indicative of the modern Premier League game. There is a huge gap between the front and back lines, with an absolute cavern in the middle of the pitch.

Both sides have a totally over-burdened six. If the attacking 6 can use this space to dribble, or immediately fire off a line-breaking pass, they are worth their weight in gold; if the defensive 6 can eat up space and destroy players in an ocean of isolation, they are worth their weight in gold, too. This is the difference between a Very Good Midfielder Trying to Play Alone as a #6, and one who is worth £105 million.

In a similar clip, I was also encouraged by Nelson’s ability to rotate, cover, and actively contribute.

The next pass didn’t fully come off, because it’s the recent Arsenal run, so of course it didn’t. But when you hear that “tackling is playmaking,” consider the type of blocks that Arsenal usually faces, and how hard it can be to create chances. Then, look at the opportunity a press can create.

If there’s one reason to feel bullish about the rest of the year, it’s this. I have seen few, if any, teams in the world who can compete with Arsenal in terms of pressing discipline and structure. That is especially prevalent here, in a game in which Jorginho was playing in a different spot than usual, Kiwior was in at left-back, Nelson was in for Martinelli, and Havertz was running things up top. The system and the training are a floor-raiser.

👉 An improvement in dynamics

We’ll get to the more critical (i.e. negative) stuff in a moment, but there was another really encouraging part of the FA Cup game: a new variation tactical set-up.

Let’s review some of the recent options at Arteta’s disposal.

♦️ Option 1: Ødegaard dropping

In recent weeks, we’ve observed the effectiveness of Ødegaard’s shift to a lower, freer role. We’ve dubbed it “Fløategaard,” and readers have shared that “fløate” apparently means “cream” in Norwegian. Take that as you will.

It often takes the form of Ødegaard dropping into a double-pivot with Rice. When this happens, he is filling these obligations instead of the inverted left-back, manned by Zinchenko in the below sequence. While this looks like a relatively standard 4-2 build-up, it’s a little bit different.

Count the Brighton advanced pressers in this situation. OK, I’ll do it for you: there are 5. When you add Raya and Zinchenko to this, you have a 7v5 in lower build-up. With Zinchenko free from core responsibilities, he can count accordingly — as you see him doing here — and go freelancing right from the earliest stage. His teammates already have them outnumbered.

Zinchenko has now left the picture. The double-pivot has dragged the midfielders around, and Raya is able to bypass the press with one pass to Jesus.

…and as you’ll see, Zinchenko is not in the spot we’d often associate him with (within the midfield pivot). The Ødegaard role has freed him up to do that as he sees fit, but he also has more freedom in an off-ball sense, which helps rush up support to the left side with more velocity. In this setup, you’ll see him doing more semi-decoy striker runs, often trying to penetrate the last line.

We’ll stop there.

Here’s the TLDR: this shift from early December has led to way more shots, way more progression, way more key passes, and way more non-penalty xG. The shots haven’t gone in, but to my eyes (and likely yours), it has been a clear upgrade to the underlying dynamics.

There are some cons to Ødegaard fixing everything, which we’ve also outlined. Among them:

Burnout: If used every game, this carries a potentially unsustainable strain on him and Rice. Ødegaard is leading the press up top and much of the build-up down low, and Rice is left all alone in transition without the full-back or a deeper midfielder tucking next to him. It requires so much running, and we saw those chickens come to roost against Fulham. They were spent.

Depth: This is a related point, but: nobody else can do what they do here. If Arsenal become dependent on this dynamic, and either of them misses time, there aren’t others who can easily carry the torch.

Transitions: With more fluid build-up, there is a little more risk when a ball is lost. Players can be caught transitioning between zones of the pitch, and lanes can open.

Adjustments: With players arriving in the box in slightly new configurations, I reckon there has been a legitimate adjustment period for the final actions — passes are received at slightly different angles and positions than usual, and this may be affecting the shooting form.

Make no mistake, this approach is filled with advantages, particularly when the left-back is Zinchenko and the opponent is a little overmatched (or playing in a low-block). The build-up phase is able to take pressers out of the equation, and the ball is able to arrive in the attacking third with a little more variance and threat.

But it can’t be the only option. This takes us to what we saw in the FA Cup.

♦️ Option 2: The updated double-6

The “Fløategaard” role is not really what we saw against Fulham, when everybody was exhausted and some practical concerns got priority.

It was also not what we saw against Liverpool, when Jorginho joined the lineup. Crucially — and in a change from anything I remember this year — Jorginho was on the left side by default, and this was a true double-pivot.

In previous iterations of this, Rice was on the left, doing something a little closer to what Xhaka did last year. Here’s a look at how they lined up against Man City.

…but, from there, he could also swing up as a more typical left-8, while Zinchenko tucked into the pivot. This is probably the closest analog to the “Xhaka role” as we’ve seen this year.

This deserves a few speed-bullets of its own:

Rice is talented, bursty, and enormous as a typical left-8. It allows him room to carry forward and places him further up in the press, which can place his ball wins up higher, and help him challenge the opposing 6 more directly.

By eye test, he has untapped potential as a playmaker up there.

In defensive transition, however, this is not his ideal role — as he can be caught up the pitch, and too easily avoided. He’s best when he’s unavoidable.

When Jorginho is deepest-6, he obviously is smart and anticipatory, but he has obvious disadvantages when covering big spaces. To do the above, it may require the team to line up in a fairly low-to-mid block, as they did against Man City.

This brings us to the FA Cup.

What we saw was a fairly standard 4-2 build-up shape, with Rice on the right and Jorginho as the on-paper “#8” on the left. While they could swirl around, change sides, or stagger their positioning, I would say this was the “default” look.

This is simple, uncomplicated effectiveness. The goalkeeper is where the goalkeeper goes. Kiwior is out wide as an actual full-back, instead of a pseudo-midfielder. Two good build-up midfielders control everything.

At times, the pivot would stagger around, showing different angles. Jorginho would often play a little bit lower than Rice when looking to receive. They would occasionally switch sides with easy fluidity.

...and now that play has progressed into a more advanced area of the pitch, Kiwior is free to join the “front-5” in attack, which also frees up the left touchline for the striker or the left-wing to drop into. When you compare it to a screenshot of the previous “option,” you’ll notice that Kiwior waited until the ball was further up the pitch to start pushing forward.

You may remember such movements from Tomiyasu throughout the year. It’s hard not to picture Timber doing similar things for longer periods, and we got a brief window into that.

Early on against Liverpool, we saw one of the benefits of such a reinforced build-up. With six Arsenal players involved deep, it is necessary for the opponent’s press to commit six players forward to compete, or there is always going to be a 2-man advantage for the home side.

In the second minute, 5 pressers are drawn forward, and Mac Allister is also in the middle of the pitch (making it 6). This leaves a simple set of 1v1s in the backline. So much of football is a simple counting exercise. Reiss Nelson makes a run in behind, and Ramsdale delivers a perfect ball. It was very nearly a goal within minutes.

Here, you can see another of the many small advantages it brings. Keep your eyes on a subtle move from Jorginho.

Even before Rice is able to receive, Jorginho sees that he’ll be able to turn and drive forward. So Jorginho does a slightly angled coverage run behind, which achieves two things: it gives Rice a fall-back passing option if his carry doesn’t work out, and it also covers a potential ball loss. This is something not really offered by his other pivot partners — Ødegaard, Zinchenko, etc — who are coming from other positions, and it’s one advantage of the “double-6” thing we saw against Liverpool.

So what’s the TL;DR on this one?

There are no smoke and mirrors here. There are a million obvious benefits to this setup. It’s just good players doing what they do best in easy-to-grasp ways.

The best example of that is Rice. There are more trade-offs with his other modes of playing. If he plays as a pure lone-6, he’s in his best defending position, and great overall — but he can miss the progression support from either Zinchenko or Jorginho, and is too restrained vertically, making it hard for him to burst forward on the carry as much as he (and we) would like. If he’s a #8 like Xhaka, he can be all-action and exciting, but it risks dulling a bit of his best-in-world defensive prowess; opponents can simply pass down the other side. This, on the other hand, is the best of all worlds: he can be in a prime spot for defensive destruction, and he can be fairly aggressive in attack. If I had to pick his “forever home” as a player — and I don’t think you really have to — it would be something like this.

This formation is really interesting for the purposes of future transfer windows. It’s not difficult to imagine Timber (or somebody even more expansive, such as BBQ-endorsed Ferdi Kadıoğlu) in that left-back-to-attacking-midfield role; there are a lot of defensively-sound midfielders who could probably do it, too. Picturing players like Zubimendi, Onana, or Koopmeiners in Jorginho’s role also makes a lot of sense. There are some fair questions about whether Zubimendi is quite athletic enough to be a lone #6 in the Premier League, or quite expansive enough to be a more advanced midfielder, but this role is absolutely purpose-built for his abilities. There are parts of his game that would be better than Jorginho’s: he’d be able to cover space behind Rice carries with more range. It’s fun to think about.

What are the trade-offs?

First, our current left-backs all come with some trade-offs in this setup. This turns Zinchenko into more of an off-ball mover, and of course he has his 1v1 defending issues. Kiwior offers the pace and wide passing range, but is still struggling to demonstrate his abilities in possession, may never go bang in those advanced positions, and is adjusting to wide 1v1s as a left-back. Tomiyasu has more half-space potential than I thought, but a) this makes him run a lot and b) I struggle to project him in the highest tier in the attacking third. But maybe he can keep proving me wrong. For my own expectation management, I have to keep telling myself that Timber isn’t coming back anytime soon.

Second, this is a little bit of build-up overkill for opponents that don’t press, which is most of them. In those situations, the team could use a bit more of an attacking edge in the front line.

We’ll see how this evolves, particularly as Partey is reintegrated into the role. But I think something pretty durable was discovered there against Liverpool.

Which brings us to another shape we saw, but later.

♦️ The 3-4-3 (🚧 under construction 🚧)

This shape can be called a few different things, from a 3-1-6 to whatever you want.

Me? I turn to the description of Fábio Vieira earlier in the year: “3-4-3. Diamond.”

We’ve seen this in fits and starts throughout the year. When Arsenal were chasing a late goal to even the score in the Community Shield, this is the setup that delivered it.

Early in the year, Arteta experimented with a version of it against low-blocks. Instead of it being a “truer” 3-4-3, it was a more standard starting position, with Partey inverting from right-back. It was interesting, especially when it came to Rice and Havertz. But it also didn’t fully deliver the advantages we may seek.

And lately, this shape has only come into play when Arsenal chasing goals and extra attackers are needed.

Aston Villa: At 94’, Trossard/Havertz/Nketiah were all on at the same time.

West Ham: Near the end, there was a bit of it with Rice at the base with Nketiah and Jesus up top — essentially forming a striker tandem.

Fulham: that striker tandem played late again.

The Liverpool game was closed out with this look. It was very late, and only got about 8 minutes of run time.

So, how are things working out when chasing goals?

The first thing we can do to understand this question is how Arsenal are doing in various game states. First, we’ll look at it by half, with numbers pulled from FootyStats:

First half

23/24: 6-10-4 in the first half (14 goals, 9 against in 20 games) — 1.4 ppg.

0.7 goals per game, 0.45 against

22/23: 20-11-7 in the first half (41 goals, 16 against in 38 games) — 1.87 ppg.

1.08 goals per game, 0.42 against

Second half

23/24: 11-4-5 in the second half (23 goals, 11 against in 20 games) — 1.85 ppg

1.15 goals per game, .55 against

22/23: 19-10-9 in the second half (47 goals, 27 against in 38 games) — 1.76 ppg

1.23 goals per game, .71 against

I could have turned that into a chart, but hey, that would have taken another 15 minutes.

Year-over-year, the biggest gap in scoring for Arsenal is in the first half. This makes sense, as teams are more likely to sit back early, and the team looks to show possessional control before upping the volume over time.

The second takeaway is that Arsenal have actually had a better record in second halves (though it’s marginal), and the defensive numbers have improved, but the goals have gone down. This, basically, isn’t ideal. Games are much longer, and stoppage time should result in more goals. This would lead us to believe that there may be some more adjustments needed.

Next, we’ll look at goals per 90 scored by different game-state, as reported by Understat.

As you’ll see, Arsenal have scored a bit less in every game state — but the biggest gap is when they’re down. While this data is a little bit small and noisy, this would lead us to believe that the adjustments to chase goals have not quite turned out to the level expected.

Why is this?

It’s a good lead-in to our next section.

😤 Verdict: Respect the power of complementary profiles or perish

Antoine Griezmann may be the non-Arsenal player I enjoy watching most.

As I was watching him play this week, I was thinking about how he’s a manager’s dream, running around, doing absolutely everything, and doing it well. How he seems to be fully set-up proof. And then I thought to myself: Wait a minute. Griezmann struggled, dummy! Even more, he struggled *because* of a profile mish-mash with Lionel Fucking Messi and Luis Fucking Suarez!

If he’s not immune to his surrounding dynamics, well, nobody is.

If I have a single gripe with Arteta this year, it’s not about his desire for control. It’s not about slowing things down. It’s not about not playing the youth enough. It’s not about the timing of subs. It’s not about Havertz or anything like that.

It’s about these complementary profiles.

The problem starts with a good thing. He has created a squad with flexible players who are nonetheless specific. They dramatically differ from one another, even if they ostensibly play the same position.

For example: Jesus, Nketiah, Havertz, Trossard, and Martinelli can all play striker, but they contain nearly every type of body-type and play-style imaginable. At left-wing, Martinelli and Trossard are not the same. At left-back, Jakub Kiwior is two Oleksandr Zinchenkos in a trench coat. The most striking example is that of the “left-8” position: on paper, Declan Rice, Kai Havertz, Fábio Vieira, Leandro Trossard, Jorginho, Emile Smith Rowe, and Mohamed Elneny have all played the same position this year.

My issue, then, is when a new player slides into the lineup, but all of the dynamics that surround that player remain the same.

This was probably most apparent against Fulham.

Arteta was working with a short deck here. Zinchenko was out, Jesus was given a breather (tactical or otherwise), and Ødegaard and Rice were exhausted. But still:

Kiwior had to jump in for Zinchenko, which is a move I support happening as much as needed. But without Zinchenko and Jorginho playing, or Ødegaard dropping with regularity, you can’t really expect dynamic progression to continue without missing a beat. Assuming Jorginho was available to play (he made the bench), he should have gotten the start, and Kiwior could play out wide.

The Nketiah/Havertz/Martinelli trio doesn’t look to have complementary dynamics to me in standard (or negative) game states. If Nketiah starts at 9 and Martinelli at left-wing, then the left-8 can be a better passer: Rice, Jorginho, Vieira, etc. I think Havertz clearly looks best at left-8 when paired with a false-9 (Jesus or Trossard). If for any reason this trio starts, the game plan should reflect their strengths: endless crosses should be pounded in with Nketiah near-post, Havertz far-post, and Martinelli in the soft underbelly.

This is why I’ve come to see the squad less as a set Starting XI with like-for-like replacements, and more as a set of complementary “pods” of players who build ideal shared dynamics. If Kiwior starts over Zinchenko, the rest of the team shouldn’t remain unchanged; if Nketiah starts up top, perhaps a different profile than Havertz should be brought into the left-8.

For that reason, one “pod” I would like to see is Vieira (left-8), Martinelli (left-wing), and Havertz (9) — which seems to be a great blend of rotations, killer balls, work in the air, and more.

🔥 Billy’s Tactical Wishlist

With that, here are a few, incomplete ideas for bringing the squad to their best in the final push.

1. Bid farewell to noble experiments

Generally speaking, there are two tactical setups that I’d probably say farewell to for the rest of the season: Kiwior as a full midfield pivot, and Havertz as a full midfield pivot. If either of them rotates there at times, all good. I’m open to Kiwior developing at this in the future. But the other set-ups just look stronger at this point.

2. More complementary pods

To highlight four relevant positions, perhaps the setup is something like:

Facing Lowest Blocks:

Rice (lone 6) / Havertz and others (left-8) / Ødegaard (dropping) / Jesus or Trossard (False-9)

Default + Facing More Evenly-Matched Teams We Seek to Press:

Rice (6/8) / Jorginho/Partey (6/8) / Ødegaard (floating #10) / Whoever (9)

In Highest-Difficulty Away Games (i.e. Man City, UCL):

Jorginho/Partey (6) / Rice (left-8) / Ødegaard (#10) in a compact, mid-block / Havertz (9)

I’m open-minded about the “diamond” look against the lowest blocks, but it’s hard to put too much stock in Thomas Partey or Jurrien Timber as running full-backs at this stage. If it’s a straight-up 3-4-3 (i.e. without a full-back), I think the #10 at the point of the diamond should probably be a snappier, all-angles playmaker like Vieira or Trossard.

3. Real chances for real talents

I tend to think Smith Rowe and Vieira should be given every opportunity to succeed down the stretch, as either of them could be the difference between the highest of highs and a slightly underwhelming finish. The dynamics are set up well for them. Both of them can sit on top of a double-pivot as a free #10, or have a freer “left-8” role while Ødegaard drops.

I also think Reiss Nelson has earned a bit more playing time. Perhaps the best bad idea I can offer you is having him as a RWB next to Saka, performing overlaps and cut-backs.

4. Platform the biggest strengths of the players

There are four areas in which I think some enormous player strengths are under-used at the moment.

Martinelli: With some of the dynamics elsewhere improved, a lot more hopeful transition balls should get hit to Martinelli (and he should cheat more), and he should crash that central area of the box with more regularity for cut-backs and crosses.

Havertz: Way more far-post crosses to him, please.

Rice: Especially in this “double-6” formation where he’s more likely to be covered by a midfield partner, he should unsettle blocks through central carries with a lot more frequency.

White: Should have a more expansive passing range. This leads us to the next point…

5. Faster switches

Arsenal are facing the lowest defensive actions in all of Europe. There were times that West Ham put all eleven players in the box. Premier League teams are fast, strong, and disciplined at maintaining their shape.

How do you get them out of their shape? First, through unsettling, dynamic, opportunistic carries. Second, through snap-fast and unpredictable rotations.

The other way is through immediate switches of play from one side to the other. I say “immediate” because these runs of play have been the biggest bummer of the season for me. Look how easy it is for a team like Fulham to reset their block when the passing looks like this.

What’s the antidote? Skipping the layovers, and looking for more direct flights. This is the concept of “manipulating flow.”

Last time we spoke, we outlined how dangerous more direct play between the wingers can be. Look at the clip above against Fulham, and then watch the below from last year. Look how impossible it is for all the defenders to fully defend one side, then the other, then the other again.

That’s why I think one of the most under-used skills in the squad right now is the more expansive passing ranges of White and Saliba. I tend to think that if Saka gets doubled, he taps it out to White, and White delivers an immediate switch to Martinelli, who then plays it back centrally or takes a chance himself, a lot of good things can happen.

While White has done a commendable job of performing some right-back responsibilities that we may not have predicted would be in his bag, this kind of pass is fully within his comfort zone.

🥅 A few finishing thoughts on finishing

As we’ve covered elsewhere, individual finishing is highly variable and fickle, and creating chances is a bigger indicator of long-term success. The good news is that those chances are being created of late.

That said, a more straightforward thinker may also posit the following: Arsenal create a lot of chances for Gabriel Jesus and Kai Havertz, two of the more reliable xG underperformers in recent times, and if that is your strategy, you’ve made your own bed. And I think there’s some truth to that.

But other things are true, too.

Since December’s tactical tweaks, here are the shot numbers for Arsenal wingers:

Martinelli: 2.78 per 90

Saka: 3.87 per 90

On the year, that would place Saka second in the league (behind Núñez and ahead of Haaland, Salah, and everybody else). Martinelli isn’t yet where he could be, but this would put him past “critically low.” This is around where the famously shot-happy Rashford is, and ahead of the likes of Son.

Since December, Saka has been taking 2+ more shots per 90 (up from 1.74). He has more shots in the last 5 games than his first 12. Martinelli is up from 2.09 to 2.78. That’s better, but there is still room to improve.

Much of the point is this. In our quest for answers, we may be critiquing dynamics that are on their way out anyway. With Ødegaard floating (option #1), and the double-6 setup we saw against Liverpool (#2), there are two coherent philosophies to generate creativity, fluidity, and solidity. In the meantime, shots just aren’t going in.

But we shouldn’t be fully satisfied with that explanation. After all, teams can underperform their shot and xG numbers for long periods.

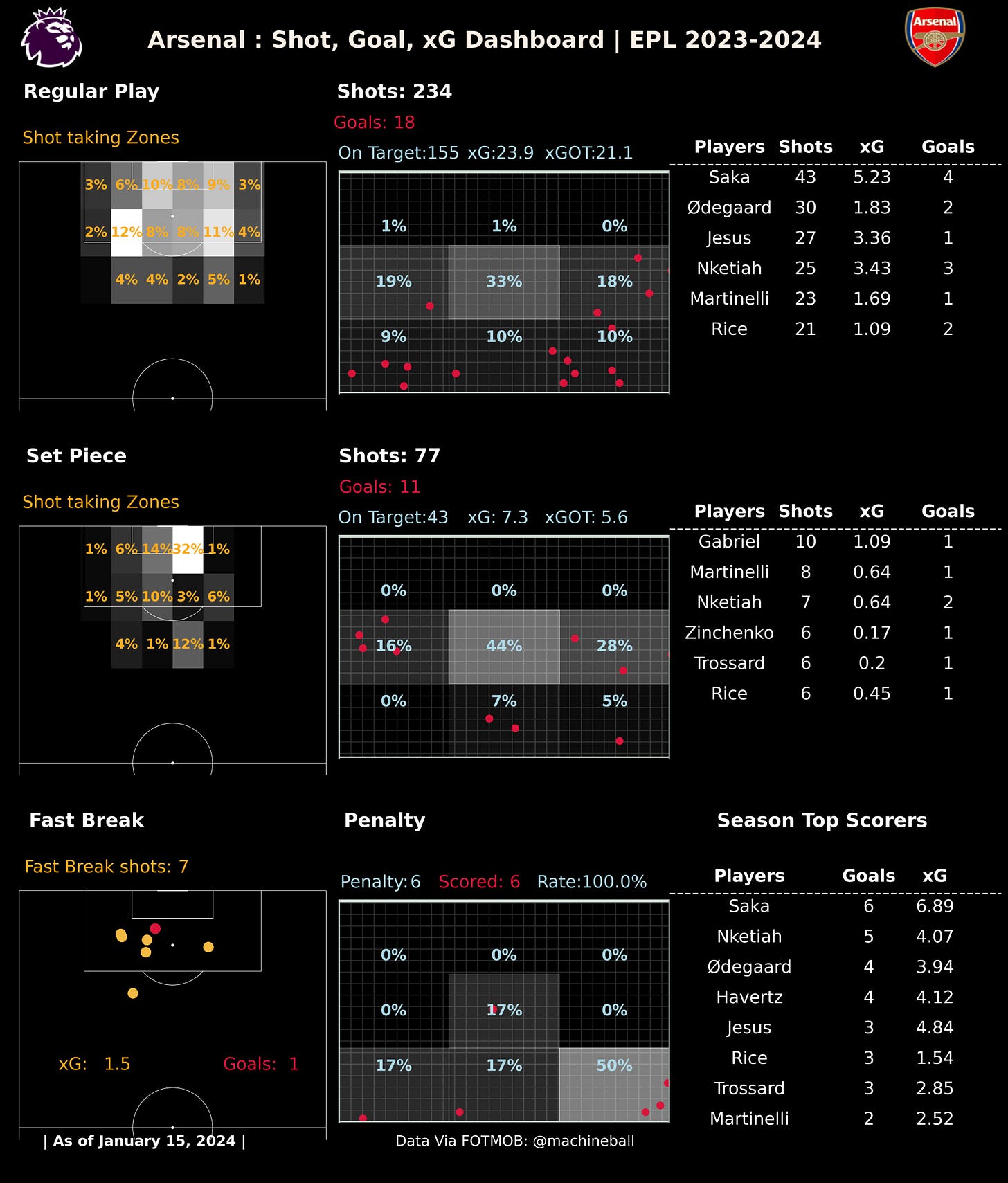

Here’s a great look at Arsenal’s overall shooting numbers from @themachineball.

How do we improve? I looked through all of Arsenal’s recent shots to get a sense of that.

In this recent piece about Reverse Engineering, there’s a great anecdote about the double agent Lee Grant, the former Manchester United keeper who is now a finishing coach at Ipswitch Town. He now helps outfield players become the stuff of keeper nightmares.

"I use that to help guide the forward players occasionally, for the sorts of outcomes that no goalkeeper would like. We talk about foot patterns, how quickly we can get shots off, arriving onto the ball as quickly as possible, shortening steps.

“I like it when our strikers are dictating to the goalkeepers. I enjoy it when we’re the ones leading the dance. If I think back to myself between the sticks, that was probably where I felt most vulnerable, when a striker had that real clarity about what they were trying to achieve and were able to do it with speed and precision.”

My most simpleton thought about the struggles in front of goal this year is just that “Arsenal are being defended like experienced Centurions, except they are all 22-years-old, and they’re figuring that stuff out, but that takes time.” Getting shots off in these boxes is just really hard.

But adjustments can and must be made, and Lee Grant hinted at the solutions above. This post is long enough, so instead of going through more clips, I’ll be quicker. A lot of this is marginal:

Arsenal are generally too demonstrative in their shooting actions. There is too much wind-up, too high of back-lifts, and too many prep touches. This is understandable against these blocks, but windows close so quickly, and this leads to a “telegraphing” problem where shots can be easily blocked.

Before the break, Saka was generally caught in between. He was going through a period where he was requiring too many prep touches before getting a shot off, and then against Liverpool and Fulham he was over-correcting, and swatting at balls a bit too much.

Probably over-simplified, but I’d ask Havertz to shoot by the first or second touch, or don’t shoot at all.

Despite how foot-dominant he is, I’m confident that Ødegaard can pass the ball into the net with his right if he trusts himself a little more.

I’d like Jesus to take shots from further away a little more often. He has really nice technique when he doesn’t dribble all the way up to the keeper and close down his angles.

Martinelli just needs to take a lot more shots and I’m sure he’ll be fine. He’s overthinking it at the moment, but when you get more reps and stop hinging your hopes on too rare of a chance, those doubts tend to wane.

Similarly, in this double-6 formation, I think the team would benefit from Rice having a few more direct shots himself — and not just long rangers.

A lot of it is just about the inventiveness of the final action, when things can feel a touch over-coached. Here’s how the brilliant Paul McGuinness puts it.

“Coaches often create a fear of losing the ball to the detriment of using small spaces to gain advantage. “Two touch” and “ball speed” are correct instructions 90% of the time — but can prevent players developing the ability to entice and commit or “go against the flow” versus opponents.”

There is a large risk of over-indexing and over-coaching these recent problems, of course.

In many ways, the season thus far can be divided into two parts. The first was a period of defensive dominance, unfinished attacking dynamics, static final-third play, quality in finishing, and kind variance. The second was a period of defensive dominance, crisp attacking dynamics, missed chances, and unkind variance.

This all requires a stubborn long view. I quoted the great director Sidney Lumet earlier in this post, and I’ll do so again.

“[You] have to watch your inner state very carefully as you come into rushes. Perhaps today’s shooting hasn’t gone very well. You’re tired and frustrated. So you take it out on yesterday’s work, which you’re watching now. Or perhaps you’ve overcome a major problem today, so in an exultant mood, you’re giving yesterday’s work too much credit.”

Now, another period beckons, and hope springs eternal. There are many logical reasons for that hope. Arsenal are perhaps the preeminent defensive force in Europe. Many of the attacking dynamics are greatly improved. Some promising chips — especially in terms of players returning to health — are ready to be pushed into the middle.

But the window of error is so slim. There is no guarantee that variance will swing dramatically the other way, or even if it does, if it’ll be enough.

Maybe it’s better to ignore all that. In this season’s obsession with control, all you can really control is your own performance.

I hope this all found you well. Looking forward to watching this one and seeing what we can learn.

Be good. ❤️

Was giving some thought to the 4-2-3-1 Liverpool setup recently, and I actually think one of the biggest beneficiaries could be Smith Rowe.

In our 4-3-3, I don’t think he’s quite winger-y enough to play Martinelli’s role, but I also have reservations over him as a traditional left eight that needs to operate in deeper areas.

But on the left in a 4-2-3-1, with an overlapping full-back, he’s much closer to the happy dynamics he had in 2021 that brought him all those lovely goals.

Any thoughts?

Nice read! Particularly loved the tactical wishlist and the discussion on complementary pods. Really well argued and hard to disagree with the setups laid out, putting together some floating ideas I had in my head into a clearer picture.