Cause for celebration

Observations after an uproarious win against Liverpool, with thoughts on the lineup selection, the sneaky directness of Jorginho, the big brain of Havertz, and some open questions ahead of West Ham

“You've seen the sun flatten and take strange shapes just before it sinks in the ocean. Do you have to tell yourself every time that it's an illusion caused by atmospheric dust and light distorted by the sea, or do you simply enjoy the beauty of it?”

― John Steinbeck, Sweet Thursday

Life is too short for decorum.

I hope this e-mail finds you well.

This has taken a bit to get together — too much celebrating, you see — but as we regroup and look ahead, I thought we’d still dive back into Liverpool. While it’ll be fun to relive a great performance and a meaningful win, more than that, I wanted to consider what it may teach us about Arsenal in the months ahead. As the games raise in stakes and the Champions League beckons, there is much to learn from our approach against the Premier League leaders.

West Ham, looming tomorrow, is a different beast — a beast who cares not for your “underlying performance,” looking to frustrate your attack and then punish mistakes mercilessly. It will require a different set of tools.

Let’s look at what tools were used against Liverpool.

✌️ The lineup selection

I have a theory that one of the best ways to learn about a manager is by investigating their most frustrating defeats. Just yesterday, I was watching an old interview with Thomas Frank, manager at Brentford, in which he was asked how he learned to be such a thorn in the side of top teams. His answer? He had managed Brentford when they were a dominant, top-of-the-table outfit — in the Championship. He simply adopted the tactics he most despised facing back then.

Meanwhile, it doesn’t require a private investigator to see how Pep Guardiola’s previous frustrations in the Champions League at Manchester City may have informed his transfer priorities and tactical arrangements over the last couple of years, helping them take the title home last time out.

Arteta, too, was probably impacted by such losses.

As he prepared for the biggest game of the season thus far, he decided on a “4-2-2-2” — with four defenders, a double-pivot midfield, two wide wingers, and the Ødegaard/Havertz duo playing “dual 10’s.”

Here’s what that looked like in the second half.

This may have looked familiar.

For one, this is the general build-up shape that Roberto De Zerbi used to humble Klopp last year. For another, it was also — trigger warning — what Guardiola used to humble a stricken Arsenal last year in the 4-1 drubbing last year. I didn’t have a good time.

Now, De Zerbi didn’t invent this, and neither did Pep. But when you look at the screenshot above, a through-line emerges: a standard back-four; a genius veteran (Gündoğan) dropping to form a true double-pivot; a target man and a #10 sprinting through the middle; wingers making associative runs off their work.

When preparing for big games, one gets the sense that veteran managers turn into the Joker: “Do you want to know how I got these scars?”

But that was not the only disappointing result that may have informed this set of tactics. Last year, Arsenal were up 2-0 at Anfield but wound up conceding a draw. It could have turned out even worse, if not for some heroics from Ramsdale and the like.

While vibrant early, Arsenal got skittish, creating bouncing balls through clearances, and then lacking the athleticism to pick them up with enough regularity. As an example: Holding would clear it, then an Ødegaard/Xhaka/Partey midfield wouldn’t necessarily come down with it. This resulted in 200 overall recoveries, with Liverpool winning 112 of them, including 26 up high. It became a tidal wave of pressure that played right into Liverpool’s hands.

Two things were lacking: stable passing, and the advantages to win second balls.

Arsenal went into the summer with a focus on bolstering team depth and raising the level against these top sides.

Back in July, a couple of weeks before David Raya was officially signed, I shared this:

Draggable man-to-man presses everywhere. Elite first and second ball players (Havertz and Rice) joining. A squad that already mixed up long and short distribution more than top rivals. Now, Raya. A coherent narrative.

…and here was the first comment, from @InfiniteStreng4:

Exciting times, I actually think we will peak around Feb/March in terms of cohesion! Hopefully works in our favour

A good call, we hope.

But that was not the only Liverpool game that seeped into the plan here.

Arsenal, of course, fought Liverpool to a 1:1 draw at Anfield in December. That game could have gone either way, and the energy from the away eleven was tremendous. In the decisive moments, things were made a little too easy on Salah (who was isolated on Zinchenko), Alexander-Arnold (who often got space on the ball), and Konaté (who was able to play to his strengths, swinging out wide and defending Martinelli without a trade-off in doing so).

To help, Konaté would often have Alexander-Arnold and Szoboszlai dropping behind him for support. As a result, our arch Liverpool killer, Martinelli, was 3/15 in attacking duels.

Cue the FA Cup. In that one, Arteta debuted a new look — with Jorginho and Rice forming a double-pivot, but Jorginho floating on the left instead of putting Rice in the Xhaka role of last year. They’d swirl around and support one another. In build-up, it looked something like this.

It was … utterly dominant. Kiwior was in a better position to succeed out wide, and crucially, Rice was able to play in his world-best defensive role. Though Klopp made some changes that improved things in the second half, I’d argue that they didn’t change many of the structural advantages that Arsenal had. The Gunners just missed their chances (fuck), and Liverpool got a Kiwior own goal off a free-kick (double fuck). Arteta justifiably over-committed attackers forward from there and Díaz scored late to make it 2-0 (triple fuck).

Fast forward to Sunday.

If Gabriel Jesus was healthy for this one, I think Arteta had an awfully tough decision on his hands. Havertz has demonstrated his advantages as a big-game #9, and especially after watching him follow around Alexander-Arnold in the FA Cup, I thought it’d be really hard to drop him from this one.

But if Havertz dropped into the midfield, there may not be enough solidity in the build-up.

Once Jesus was ruled out, I thought the gray area disappeared, and there was a clearly-correct lineup to choose. Arteta chose it. This was for two reasons:

Havertz provides the ability to play over the top of the press. He and Rice also add the athleticism that was so lacking in second balls last year at Anfield.

Jorginho provides the line-breaking, control, and communication needed. In addition, if you play Havertz in the left-8 for Jorginho, you’re forced into the sub-par complementary dynamics that we’ve discussed before. Martinelli/Havertz/Nketiah just doesn’t feel like a trio that brings out their best in this one.

Which brings us to the first decisive moment of the game.

💥 The breakthrough

Here’s how we discussed the advantages of this Arsenal set-up last time out against Liverpool:

There are no smoke and mirrors here. There are a million obvious benefits to this setup. It’s just good players doing what they do best in easy-to-grasp ways.

The best example of that is Rice. There are more trade-offs with his other modes of playing. If he plays as a pure lone-6, he’s in his best defending position, and great overall — but he can miss the progression support from either Zinchenko or Jorginho, and is too restrained vertically, making it hard for him to burst forward on the carry as much as he (and we) would like. If he’s a #8 like Xhaka, he can be all-action and exciting, but it risks dulling a bit of his best-in-world defensive prowess; opponents can simply pass down the other side. This, on the other hand, is the best of all worlds: he can be in a prime spot for defensive destruction, and he can be fairly aggressive in attack. If I had to pick his “forever home” as a player — and I don’t think you really have to — it would be something like this.

If you’re the kind of sicko who reads this, you’ve probably seen this play broken down ad nauseam. Oh well, let’s do it again for posterity. But quickly!

Here, you’ll see the build-up structure that we mentioned earlier. It’s a 4-2 with everybody in their expected situations. After manipulating the pressers a bit (especially Gravenberch), Havertz drops a little to facilitate a pass back to Gabriel.

This overloads the press and creates a free man. Look at Zinchenko in the above screenshot.

Now is where it gets important. Dropping extra players and passing through a press is no significant achievement in itself. This is an 8-man build-up, with Raya making it 9. Any group of nine professional footballers should be able to complete a rondo with a three-man advantage. Every week, you’ll see clubs with slick build-up structures that fizzle out when they get the ball forward. Why? Because they dropped so many players down. The prize for all their nice passing is a winger with a 1v4. Congratulations!

To succeed, then, there has to be a coherent philosophy for creating an advantage once the press is broken. That’s why we should watch the next frames very closely.

Next up, Zinchenko carries up the touchline and attracts the coverage of Alexander-Arnold. Again, this is expected, and the correct thing to do. Konaté then has an easy decision: swinging out wide to track Martinelli 1v1, just as he did at Anfield.

A slight vulnerability is introduced here, though. Van Dijk has been caught in two minds — both wanting to get up on Ødegaard, and wanting to hang back to sweep things up.

…and here is the key moment. Ødegaard, who is now taking up more central positions of late, gets the ball from Zinchenko — and Havertz gallops up to the backline.

The key figure to look at here is Konaté. Whereas a similar decision in the game at Anfield was simple — just follow Martinelli — here, he is presented with two bad options. This is because Havertz was immediately able to transition from dropping in build-up to probing the backline. If he dropped too deep, or took too long to arrive, or looked for the ball at his feet, the Liverpool shape gets its reinforcements and resets. But Havertz was through.

Havertz got the ball into space, unleashed a tame attempt, then Saka drove it home.

1-0.

There is another advantage to dropping players so deep in build-up: it forces a difficult decision for a modern press. If they want to actually win the ball, they have to respond in kind, and commit 6 (or more) players forward. But as soon as they do that, there are isolated match-ups on the backline. This is what De Zerbi exploited to good effect against us last year, when Brighton would pull the press forward as much as possible, before going over the top to Mitoma.

Likewise, you may remember an early chance in the FA Cup. Arsenal went with a 6-man build-up, and as soon as Mac Allister nudged forward, that created a simple 4v4 on the back-line. Ramsdale went over the top to Nelson and it resulted in a near-goal.

Before this game, I asked for a redux of that moment — except for Martinelli. We got it in the second half.

If you look above, you’ll see a few interesting details.

Liverpool were committing six players forward in the narrow 4-3-3 press. To understand their level of commitment, the positioning to watch is usually that of Mac Allister.

Kiwior had swung up to hold high width as a full-back, and Martinelli had swung inside as a striker. They coordinate their movements: Kiwior drops to help in build-up, just as Martinelli starts his run. This forces Gomez to follow a bit, which makes him less of a factor in second-ball clean-up. You’ll see a lot of coordinated runs like this on long-balls; Ødegaard, for example, is often doing inside runs when the ball is switched out to Saka.

A lot of football is just an exercise of counting the backline to understand what’s going on elsewhere. With Gomez and Mac Allister pulled a bit, that number is “3.” In other words, the opposition has lost their numerical advantage in back. It’s time to go long, and Jorginho points it out.

You know what happened next.

If that Van Dijk/Alisson interaction reminded you of the Arsenal mistake in the first half, you’d be right. There is a goal explosion in the Premier League, and I’d assume much of that has to do with how long games are. But it also seems geared towards non-standard situations, as blocks are so good and well-coached, and everyone is having trouble breaking them down. So how are goals scored? We’re left with mistakes, worldies, set pieces, and the counter-press — and the occasional brilliance like the first goal.

🔥 Jorginho, “control,” second balls, and directness

As a general rule, the more loose a game feels, the more Liverpool accrue an advantage. They are at home in these freewheeling, shot-heavy games, and are 18-2-0 when they recover the ball more than 50 times (fb-ref).

When you put Jorginho on, then, you make a clear signal that you’d like to control the game. But Arteta used a different word in the post-game press conference.

“Yeah, control is not really a word that I like. I like dominance and not allowing any teams to breathe, more than control. And especially which part of the pitch that happens in, that’s the most important thing in my opinion. But we can be very chaotic in open spaces, we can create a lot of issues playing in different ways. That’s another weapon that we have.”

Sound familiar? Here is our last newsletter.

There are a few watchwords over Arteta’s tenure at Arsenal. Many of them make the rounds as memes: passion, clarity, energy, duels. Another seems to make as many appearances: dominance.

Over the years, Mikel Arteta has sought to build a squad that is reliably capable of imposing its will on the opponent. In a variance-heavy sport, it’s not enough to play a little better than the opponent. A team must rally around a cohesive vision (clarity), drive it home with every action (passion, energy, duels), and have the physical capacity to do it over and over again (dominance).

Good timing, Billy.

In other words, a line-up that seemed to point towards “control” actually featured a really nuanced, interesting game-plan. This game accounted for Arsenal’s lowest possession of the year (43%), fewest completed passes (326), fewest touches all year in the midfield third (201), and the most overall touches against (683). Our Kontrol King, Saliba, had his lowest number of pass completions all year (30); for reference, he had 122 against Sheffield United. Considering that it felt like Arsenal generally imposed itself on Liverpool, that’s pretty surprising, ey?

It starts with how Liverpool sought to build up. They also used a 4-2, with Gomez and Jones splitting the left-most pivot. We’ll notice a couple of interesting things here.

Among them:

Jones and Mac Allister make a solid passing pivot. Gomez is also good when he comes inside.

The idea, essentially, was to have players like Jota and Gravenberch maraud above the double-pivot, and seek to get open behind Jorginho — bursting and carrying it forward before the team can regroup. Once that line is broken, Liverpool can quickly playmake.

This also involved Jones swinging out left a lot to receive the ball.

But you’ll see a few issues here, too. The biggest one: Alexander-Arnold cut an ancillary figure all game. Any good plan of attack should start from a place of “doing what your opponent wants you to do the least.” Klopp may have determined that Alexander-Arnold was a risky defender to throw in the middle in case of a ball loss, and thought that he can generate enough crossing threat from out wide. The Gravenberch/Gakpo/Alexander-Arnold triangle never looked too fluid or threatening. Whatever the reasons, I’m used to watching Trent’s every move and shitting my pants. I forgot about him for long stretches.

You’ll also see that Arsenal were baiting Liverpool into playing it out wide left to Gomez, where he’d have to use his weak foot.

I don’t know about you, but whenever Alexander-Arnold is literally out of the camera view, I am happiest.

While I was calling for a full beans press before the game, Arteta sought a slightly more relaxed, disciplined look, and he was proven right.

The game started with a pretty heavy high press, but there were all kinds of machinations from there. This stat approximates that.

Every press has its “triggers” — a loose touch, a certain player using their off-foot, a play going backwards, a ball going into a certain zone. Sometimes (like against Brighton), Arsenal hits “select all” on the triggers, going after every vulnerability. Here, it was a pretty narrow set, and the objective was to stay really compact as a team, with a narrow back-four.

The biggest practical impact was that Jorginho was rarely exposed in space, and Rice was often not far behind. Here’s his trademark.

But the other practical impact was that Liverpool slowed down a bit, and the game wasn’t a truly end-to-end affair. They wound up with 1 shot on target.

Remember how we said that Liverpool tend to win any game where they make 50+ recoveries? They had their fewest recoveries of the year on Sunday, with 36. Interestingly, they also had their fewest recoveries by an opponent — Arsenal had 36, too.

When the ball was up for grabs, Arsenal put up a good fight. According to the official site:

We won 52.3% of duels and made 21 tackles to Liverpool’s 11.

As a team we also ran 116.8km, which was an astonishing 6.1km further than Jurgen Klopp’s table toppers, with skipper Odegaard leading by example.

Covering 12.75km himself, the Norwegian put in a monumental shift that was his personal best of the campaign, and the second highest individual figure overall.

But this is what was so interesting about Jorginho’s role. While one may think he was brought on for stability and safety, he was actually direct and vertical. Look at his pass-map and you’ll see a lot of straight lines.

Watch him direct traffic here, exploit a vulnerability, create a miscommunication between Gravenberch/Mac Allister, and break the lines.

…and here was one of my personal top moments. It had everything: White toying with them; Jorginho manipulating flow; Ødegaard floating left to help; Martinelli played in behind. Check, check, check.

What you saw more of were plays like the below, designed to get Martinelli cheating and in space.

These were the passes that were missing from the Arsenal repertoire for many months of the season. We’ve seen the team back-pass in a similar situation plenty of times. Not so much lately. Arsenal played it long at the highest rate of the season.

Many of these were after longer spells of Liverpool possession or were plays directly from Raya. When the ball goes high up in the air, it takes up game time, and keeps the affair from going truly back-and-forth.

Jorginho, needless to say, was great on Sunday. Here’s Arteta:

I’ve always said that he’s an example, a role model. He’s been in a lot of pain as well, because he has an issue that he’s been carrying for months. He didn’t want to stop, he’s been playing with that, he’s been training as the first one in and the last one out, and for all the kids, for everybody at the club, you want to look in the mirror at somebody, just look at him and how he behaves. He’s won everything, and if you ask him not to play, or to play one minute like last week, he’s happy to go there. You ask him to play 98 minutes at the rhythm and he’s able to do that, so I’m really lucky to have players like this.

If Jorginho is not the worst athlete in the entire Premier League, he is in the discussion. For a player with those physical tools to get Man of the Match against Liverpool is almost unbelievable. Being pretty smart is not enough; he has to be on a different plane. He just kept winning second balls.

It’s important to note that he was not great in a vacuum, however. It required a game-plan that kept things compact around him, a pivot partner who could clean up the mess, and ample runners and athletes around.

Which brings us to his former Chelsea teammate — who was my man of the match.

🕺 The big man up front

At 15’, there is a throw-in with a heavy “crunch” on one side. Martinelli decides to go freelancing, just because. This often leads to some of his most fun play.

But as the play makes its way over to the other side, White is squeezed, and is forced into playing a hopeful ball over the top, which has no chance of completion. Martinelli is caught on the other side of the pitch.

…and crucially, his defensive responsibility has been the opponent’s best player. No worries, Havertz had already picked out Martinelli’s position and rotated down to cover.

Basic stuff? Maybe. But it keeps happening.

Later in the game, Ødegaard got caught out and stepped on by Van Dijk. There were unsuccessful pleas to stop the play. Havertz saw the captain go down and sprinted over to cover.

The job, then, is to delay the carrier to give the block the time to regroup.

The play culminates in him tracking a runner as a right-back and heading the ball away from danger.

And here was perhaps the best example — and it was one I didn’t catch until I got to rewatch the game with a wider-angle camera view.

Do you remember the Kiwior free header? It could have been a great moment.

But it could have been a great moment the other way, too.

In the below .gif, look at everybody’s body language as they react to the play. Havertz doesn’t react because he sees that his left-back is down at the penalty spot and Alisson wants to kick off a counter behind. He tracks the runner.

…and here’s where the wide view was helpful. Havertz tracked Elliott all the way back to Núñez, switched onto him, and defended him 1v1 as a left-back.

Núñez turnt him pretty good from there — can’t win ‘em all 😜 — but Havertz personally made sure that Gabriel wasn’t left in a 2v1 here, and delayed the play enough for Rice to get back and for Gabriel to be able to slide back over.

From there, his impact was easier to grasp. A rule of thumb is that Arsenal tend to go long a lot more against their best-pressing opponents. From goal kicks, for example, our 7 highest counts of long-balls are against Man City, Liverpool, Tottenham, Liverpool, Champions League, Champions League, and Champions League.

Here, the ball is ferried to Raya. He does a backline count — again, you look at how many defenders are holding the line, and that’ll tell you how many are forward. Here, he sees that only three defenders are back, which means Mac Allister and Gomez are forward.

…and in this transition shot, you’ll see that Mac Allister was pulled a bit forward in support, so it’s essentially a 4v3 on the backline. Martinelli and Jorginho are there to pull up any second balls.

…and there we have it. A “lost duel,” and Martinelli in space.

In a league of fearsome blocks, this is how you arrive into the attacking third with a sense of energy and happy disorder.

On a clearance like the below, Havertz really has no business getting anything, let alone a yellow card on Konaté — who he eventually got sent off. The fear of Martinelli sprinting in behind may have played into the outcome here. One touch his way, and he’s through on goal.

There were countless other moments like this. There was also some inexactness, some lack of conviction on the shot, and a conservative passing bag.

But when I rewatched the game — a game with Van Dijk, Rice, Alexander-Arnold, Saka, Saliba, Ødegaard, Martinelli — the single most impactful player was probably that gangly, expensive gentleman from Chelsea.

🔥 Wrapping up

Klopp had a simple analysis of the game:

“Arsenal deserve the three points, there is no doubt about that: they scored three and we had one shot on target, so that's obviously the one stat that shows the most.”

Injuries always play a role, and there may be some simple brilliance to Liverpool’s transfer strategy of stacking young, vibrant midfielders and attackers in a season that is likely to be a battle of attrition. We can do a back-and-forth on who is more injured but, yeah, the Void of Salah definitely played a role in this one. Alexander-Arnold, meanwhile, was either not fully fit or used catastrophically.

If I seem positive, it’s because we’ve seen the underpinnings of high-level form for a while now, and they are finally translating into meaningful results.

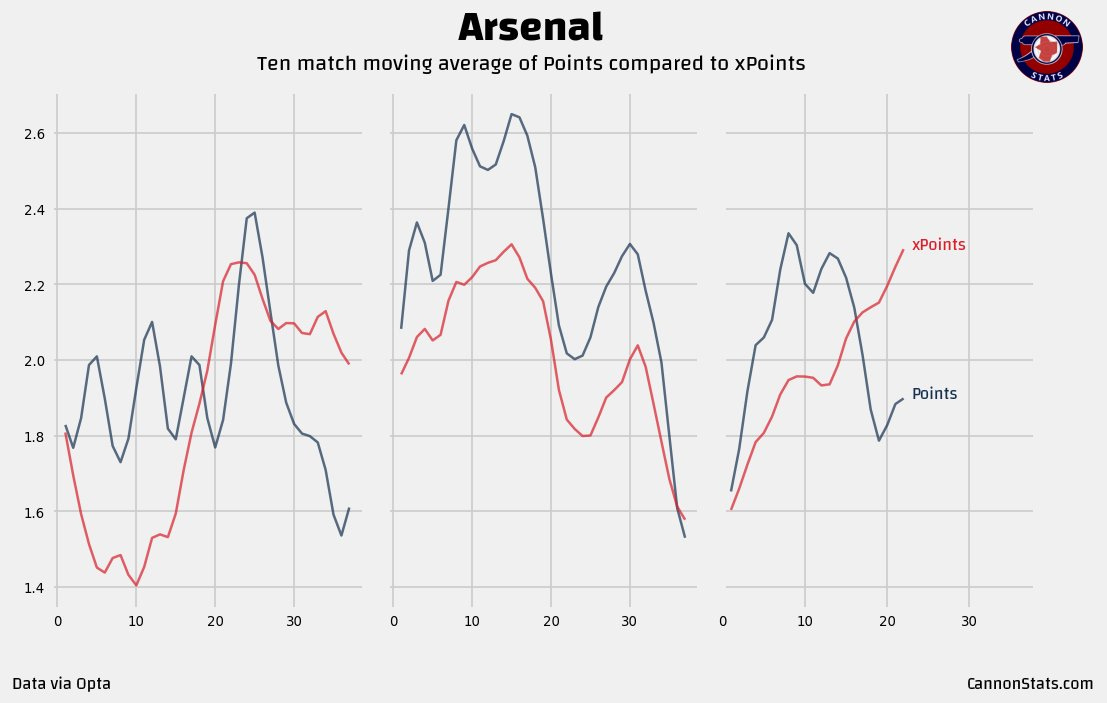

If you look at the right-most graph from Scott at CannonStats, you’ll see the story of the season so far. Some good results and “overperformance,” for a while, some great performances with fewer spoils since. If the blue and red lines get closer together, we’ll be in good shape.

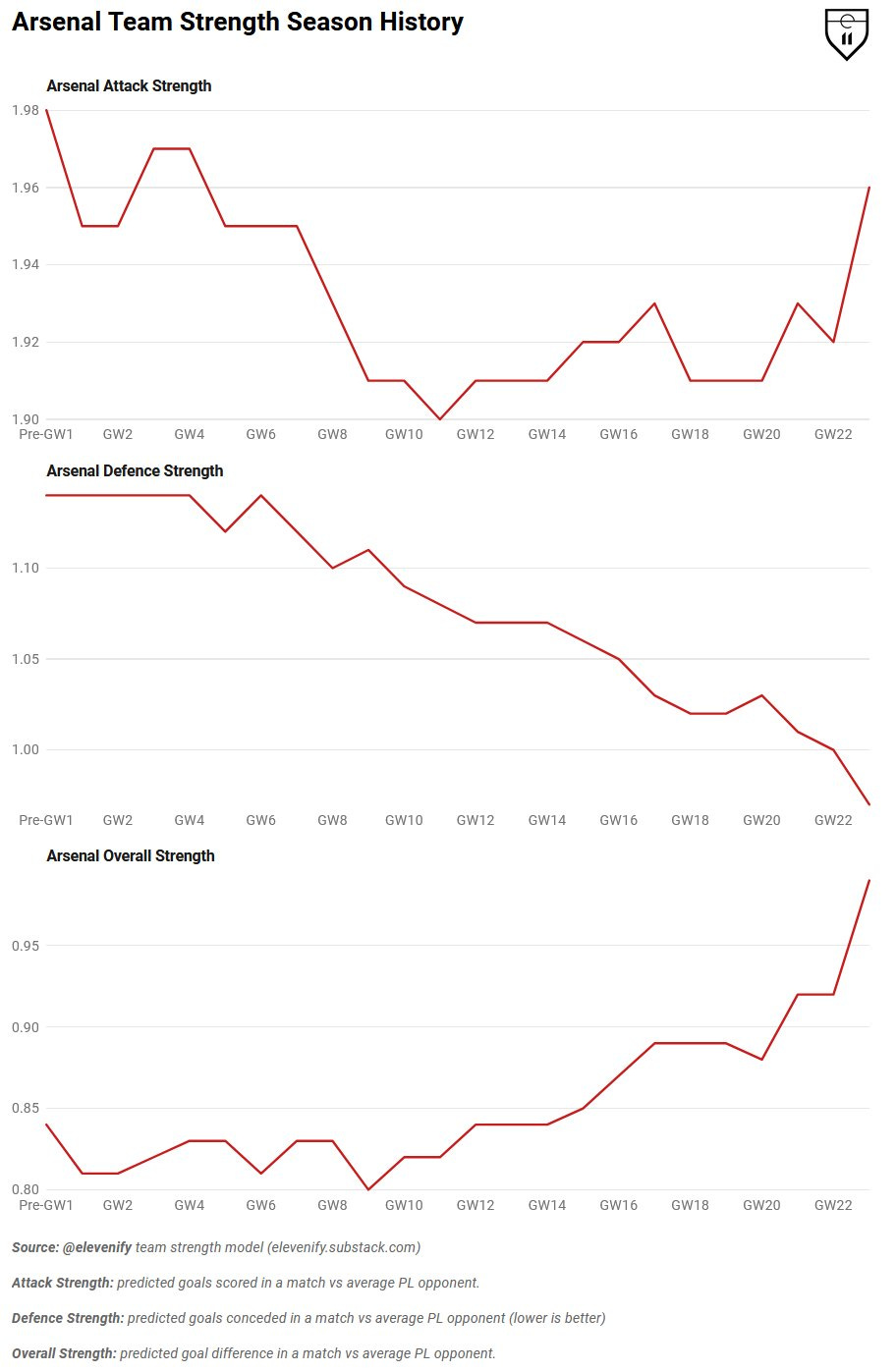

Similarly, you’ll see some similar trends in the numbers of our friend Elevenify:

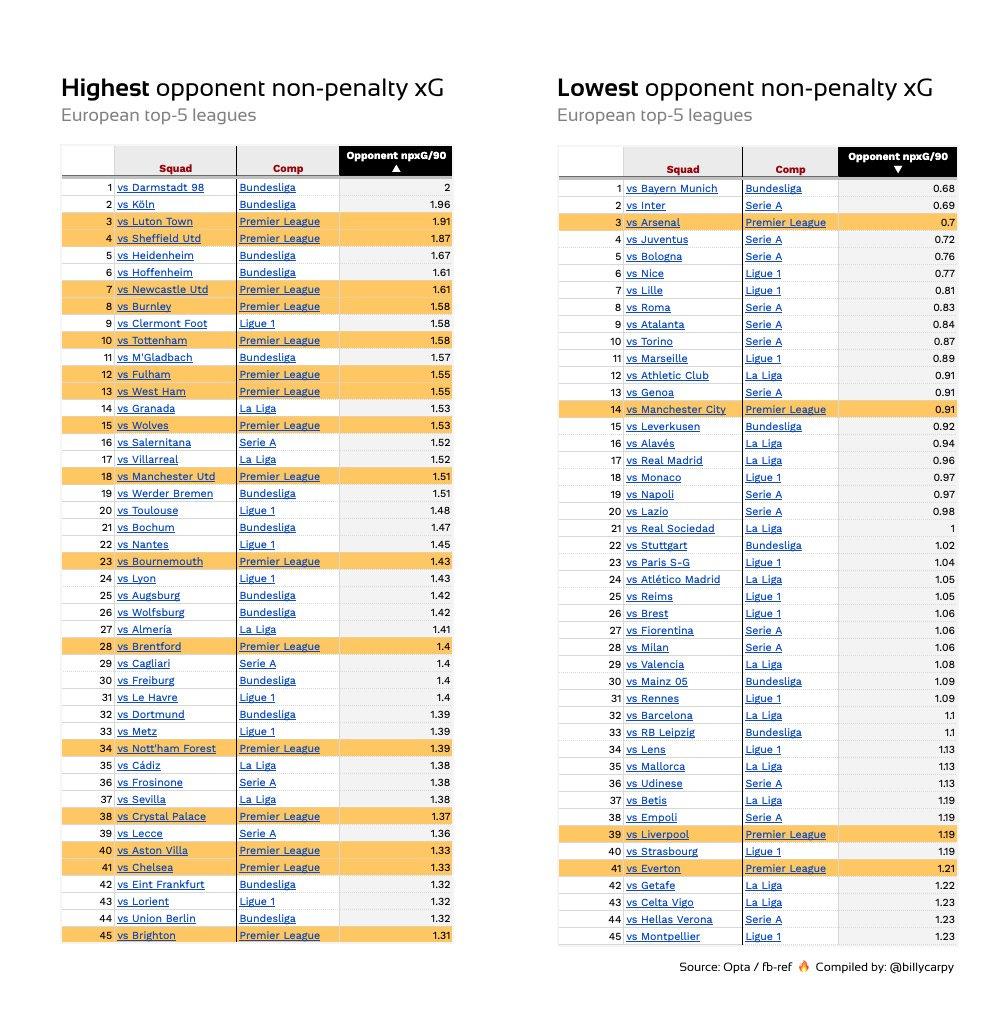

Here’s a broader trend from @FPLSeles:

I was sorting Arsenal games by most shots — and noticed there was only one appearance by an opponent in the top-20 this year.

When you take a wider view throughout the European top-5 leagues, you’ll see ample evidence of the Premier League goal explosion (thanks, in large part, to longer games). 16 of the teams with the highest opponent non-penalty xG are in the Premier League; very few make the lower end of the list on the right.

Arsenal have the most touches in the attacking penalty area in all of Europe (with 36.8/90), the most progressive passes, are second (out of 96 teams) in allowing the lowest shots on target.

But we can not be naïve. Other teams are great, too, and injuries and misfortune to not only go one way — it’ll always get better when X player is back — they can go the other way, too.

As such, here’s a quick inventory of some positives to take away from this one — as well as some questions I still have. We’ll start with the good stuff.

Jorginho and Havertz provide a durable advantage in the biggest games. In his success as the big-game #9, Havertz also potentially bolsters winger depth, allowing Jesus to swing wide.

On Raya: Here’s a very obtuse point that I'm sure everybody already gets, but it's not just [Raya claims more] + [Raya is good at quick distribution] as separate things. It's [Raya claims more] and so [he gets to do his better quick distribution at higher rates]. It’s a compounding advantage.

Ødegaard, Saka, and Martinelli are just fine. Ødegaard leads all of Europe in live-ball shot-creating actions, and Saka is third. The updates to Ødegaard’s role have unlocked so much.

It’s often accepted that Martinelli is the best finisher on the squad, but I’m not sure that player isn’t Trossard. He did get a bit fortunate here, but we’re not picking nits.

When played in this role, Kiwior is fully capable of making an impact. I remembered his duels well, but his passing was more aggressive and confident than I had remembered on rewatch. When it’s a 4-2 look and the left-back is played outside of the block, Zinchenko’s advantages can wane and Kiwior and Tomiyasu’s advantages close the gap.

White has his legs back. In a game like this, you see why Timber was a priority transfer. This right-back role is awfully hard, and is a lot easier when you’re fresh.

Gabriel is good. I don’t know what to add.

👉 Some open questions

That said, there are still some remaining questions on my mind. I’ve posed many of them through the months, and a few good performances do not wash them away. Without going through all of them, here are a few things on my mind at present.

What is the future of the left-8 against low-blocks? Whereas other parts of the set-up feel ready to go for the trophy run, this question remains open — and still in the experimentation phase. ESR, Vieira, Havertz, and others are all vying to stake their claim.

What happens if Jorginho is out? In a conversation that is usually reserved for players like Saliba, Rice, Saka, and Ødegaard — the team has suddenly built up a big game dependency on Jorginho. It’s hard to count on contributions from Partey, and without Jorginho, it’s hard to envision some big games being so successful this year.

Can mistakes and issues with set piece defending iron themselves out? The mistakes keep coming in spurts, and I think there is genuinely a little vulnerability in set piece defending. I believe it’s more structural than physical.

Can finishing reach title-winning levels? While we may expect some numbers to rebound, finishing is fickle, and the question remains as to whether it can get to the highest level to challenge Man City and Liverpool atop the table.

OK, I should probably wrap it up now.

With West Ham looming, I’d expect to see a different tactical setup, and some new entrants into the lineup. As such, the Liverpool game can only really teach us so much, and lend us so much confidence for a contest with different contours.

It’s going to be a tough one, relying on finishing opportunities, set piece defending, and composure in back.

If you want to win the title, it’s gotta be three points.

After all, the title of this piece is “Cause for Celebration.” My hope is that, the next time we speak, I won’t be using this image.

Here’s to that.

Be good!

❤️

Another thoroughly enjoyable read! Thanks Billy. It's surprising how many in the fan base are still on the fence and not "fully convinced" about Havertz. Sure, his finishing could be better but no one is perfect! Great job illustrating for folks what Arteta means when he says Havertz is such an intelligent and versatile player. Hopeful that Havertz will end up being as important a signing as Rice, just not as obvious right now.

Kai Havertz was immense. His individual performance most closely embodied what Arsenal did to Liverpool - dominance. None of Liverpool's big men could play him. If the German ever gets that final action/end product back, Arsenal have got another genuine 100M star.

Billy, your pieces have made the game a lot clearer for me, easier to see. You and a few others are leaving monster marks on fan knowledge and we're all the richer for it. Chapeau.