Kai Havertz scores again

Observations after the Brentford win and the Lens shellacking, including: game state, opponent blocks, how to go long effectively, the final third, purposeful crosses, Jesus, Fløategaard, and King Kai

After the 1-0 win against Brentford last weekend — but before the 6-0 smashing of Lens in the Champions League on Wednesday — Mikel Arteta was kind enough to write my introduction.

“Game state is a big thing,” said Arteta, prophetically. “Last year, we scored a lot of goals in the first minutes of the games and then the game becomes different — the opponents are more open up and have to do many other things.”

Arsenal faces the most difficulty scoring when the game is level. According to understat, the Gunners average 1.48 goals per 90 in such situations. In all other game states, this number rises to 2.35 or more.

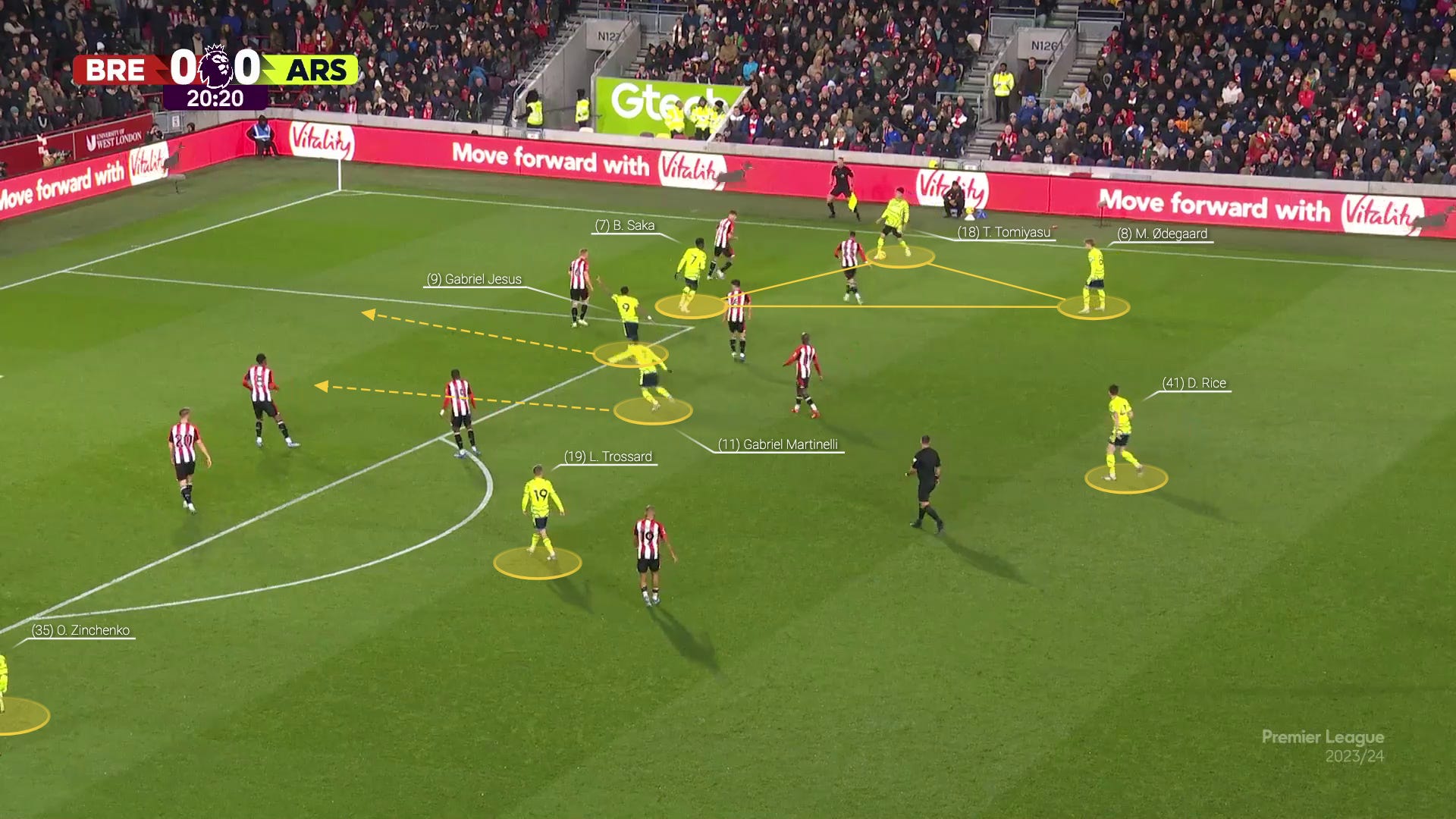

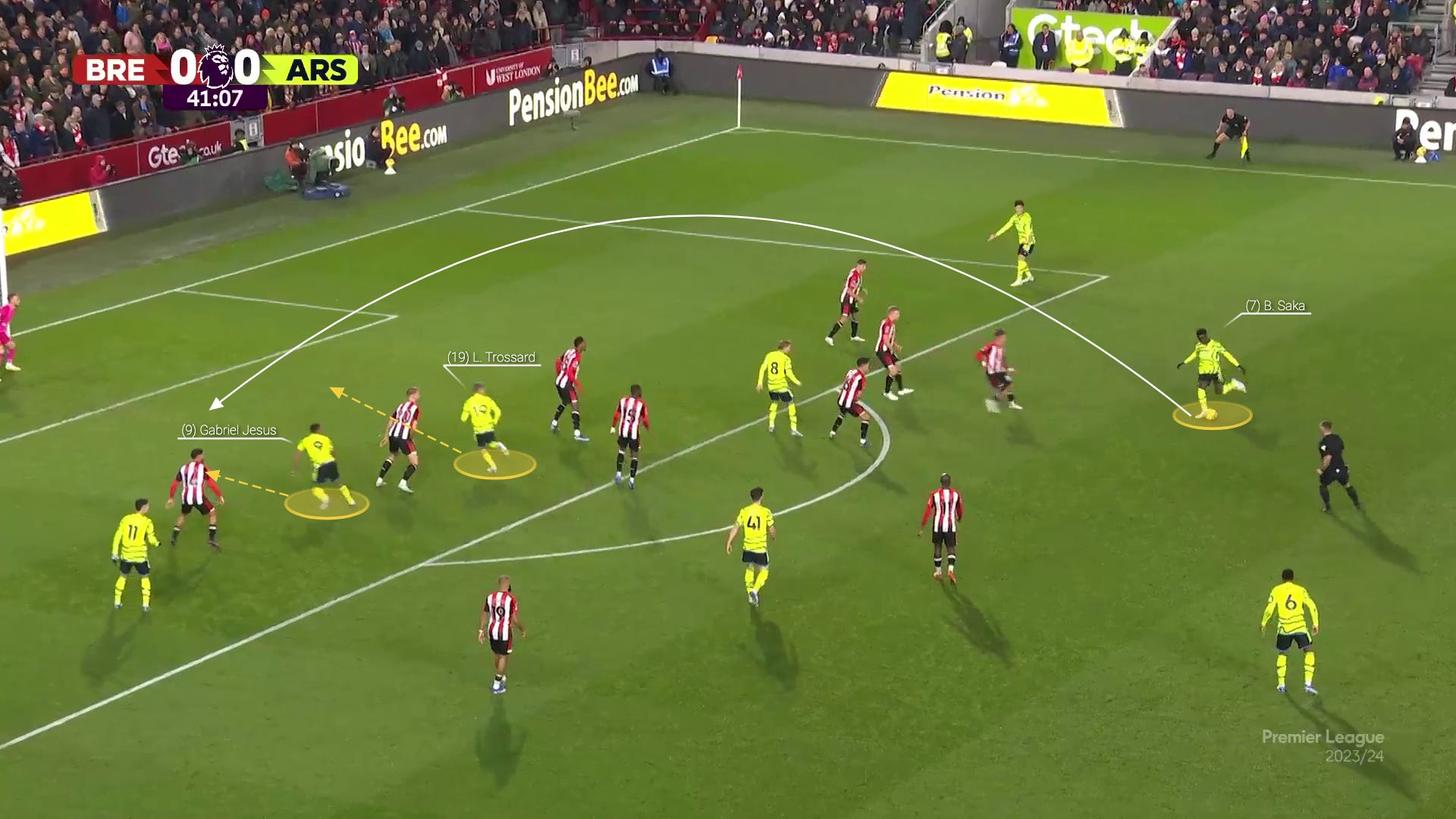

As Arteta spoke, he was coming off a game that was stressfully 0-0 until the 89th-minute winner by one Kai Havertz. Memories of a giant, low, disciplined 5-3-2 shape were fresh in his mind, and for good reason. I mean, look at this thing:

This has been a weekly occurrence in the Premier League, though Brentford perhaps did it with a little more vigor, skill, and attacking nuance.

Writing before Lens, I had this to say:

It’s hard to come across a piece of Arsenal content that doesn’t compare this year with last. I’m certainly guilty. This is to be expected, as last year was intoxicating — at least, most of it was. On the contrary, this season has vaulted the club to the top of the table, not to mention the Champions League group, but the games have generally felt more controlled, scientific, practical. Goal numbers have been down, and so are loose balls and ambitious passes. For some, this has created a desperate urge for the team to return to their swashbuckling best, risk and all. The rest of our lives can be safe and practical. This should be fun.

But the world around us does not afford the courtesy of remaining static. Yesterday’s price is not today’s price. Opposing managers and players have been reviewing tape, bringing a new callousness to proceedings. The blocks are lower, grittier, more negative. And like the adult who returns to their small hometown, we may find our longing complicated. One shop has closed, another has changed names, and there’s a new, inexplicable roundabout on the edge of town.

[…]

The hard truth is that some of that spark can be rediscovered, but much of this was cropping up last year as teams adjusted, too. The more convenient truth is that Arsenal have created an absolute monster out-of-possession, and otherwise, are looking to fashion a blunt instrument for the obstacles in the world as it is, not as it once was. The effectiveness of that new instrument — a slightly different kind of goal-scoring apparatus — will determine the ultimate trophy haul.

Our memories do not survive untouched. We miss places that no longer exist.

Or, put better: We can always come back. We can’t come back all the way.

The manager went on.

“This is exactly where we want to be. It’s not going to be as fluent, it’s not going to be as hectic, because there’s no space to run. When you’re sitting in traffic, I want to go 100 miles an hour. But I have three buses and 55 taxis and motorbikes around me, so it’s tricky.”

Within days, it was time for another game in the Champions League group stage, where opponents have allowed such space.

You’ll never believe what happened next.

👉 Different preparations

Because the broader discourse of the New Arsenal has stayed relatively consistent — better out-of-possession, less exciting in-possession — it can also risk leading us to miss the particulars of each game.

In general, following the Chelsea draw (and ignoring the League Cup, as one should), I have found more and more reasons to praise Arsenal's underlying performances. Not just statistically, but structurally. There have been subtle, welcome updates to the build-up shapes and automatisms.

When Rice and Jorginho have partnered up, Rice has stayed closer to his batterymate; the left-back (often Tomiyasu) had largely joined the frontline; Raya has looked more comfortable and fluent overall; Ødegaard, when healthy, has been more involved deep; a couple of other tweaks were present. It has resulted in a side that is starting to show some of its promise in build-up, which has a “force multiplying” effect elsewhere.

In general, it’s looked something like this.

Which brings us to the last two contests. I always like to begin by confessing my priors. I generally love, and greatly respect, how both Thomas Frank and Franck Haise set up their respective squads. Some managers have pragmatic defensive temperaments, and some have genuine attacking ambition. Few have both, and are able to so finely tune their squad to the needs of the day.

If you watch MotoGP, you’ll be familiar with riders overdriving their machinery, unable to cope with the reality that their bike may be fourth fastest on merit; every so often, this can lead to a surprising result, but much more often, it just means hasty lunges and big crashes. They wind up underperforming a slower bike.

Thomas Frank, however, always goes the right speed. It’s overly simplistic to say that he simply parked the bus against Arsenal. In fact, for practical purposes, Brentford may have been both the highest press and the lowest block that Arsenal have faced all year. This was for a few, good reasons.

Ramsdale started instead of Raya, who wasn’t allowed to play against his old club.

Trossard started at “left-8,” interrupting the Jorginho/Rice pairing which had started three straight.

Tomiyasu started at right-back over a recovering Benjamin White.

All of these points, in theory at least, should have disrupted Arsenal’s increasing comfort in build-up. Frank sought to pounce on that vulnerability. Mbeumo and Wissa would line up like sprinters at the edge of the box, crowding the space, and generally unsettling things.

As you’ll no doubt remember, this was … highly successful. Ramsdale did indeed get spooked, and Arsenal was forced to either hoof it long or deal with the consequences.

When the ball did advance, Brentford would simply sprint back and regroup into that monstrous block you saw above, which featured all kinds of deceptively simple movements and cover-rotations that ensured that switches were difficult, lanes were blocked, and genuine space was near-impossible to come by. This made things understandably difficult.

👉 How Lens lined up

Lens, lest we forget, beat Arsenal the last time out, and their energetic mid-block was annoyingly effective in France. If you feel any urge to discount this result given the opponent, take a look at their defensive performances since the start of October, then reconsider.

To continue the MotoGP analogy: Lens went for it and crashed out.

But Arsenal had a trick up their sleeve for this one: for the very first time this season — yes, you’re reading that right — Arsenal were able to start their first-choice attackers across the front five: Martinelli, Havertz, Jesus, Ødegaard, Saka. All five of them scored in the first half.

On the Lens side, the 5-4-1 featured Elye Wahi up top. Kevin Danso, who was brilliant last time out, led things from the middle. The wingers would be doubled and the middle would be crowded, per usual. The only difference? It was a little further up.

And there, you can see something else: Gabriel Fucking Jesus, Master of the Champions League.

Speaking after the game, he was asked about Arsenal’s reported hunt for a big-money striker. He was sanguine.

“I know what my qualities are and I know what I can bring to the team. I can score and I can also help with other things, like opening spaces.”

Spaces. The first goal is a great example of that, and illustrates the power of central dribblers. Jesus chooses to force the issue and dribble right at Lens.

By the next screenshot, you’ll see how disorderly things look for the opponent by the time Jesus gives up the ball. The chaos agent has done his thing.

Once it’s time for the Tomiyasu half-space cross, there’s some disarray in the Blood and Gold. But what I want you to look at here is the movement of one Kai Havertz. Look how quickly he identifies the ball floating to Jesus, informing his cut into the space. Then compare that to the recognition of the peers around him.

It’s almost like he’s good at the whole “box movement” thing!

The early goal, as Arteta predicted, would change everything. Below you can see a chart that shows Lens’ PPDA (passes allowed per defensive action), which is an imperfect stand-in for how intense their high press was. It started off low, then ramped up speed, and never went back down again.

As soon as the goal went in, Lens adjusted an aggressive mid-block to a real high press, spreading out and seeking some attacking solutions of their own. That played right into Arsenal’s hands, busting things wide open, just as Arteta predicted.

👉 Going long

Final passes may not have been an issue against Brentford. I’ll explain.

Going back to the build-up shape you saw before, Arsenal had a clear preference for playing out the back. They set up in a Brightony (1)-4-2-4, with four attackers pinning the defenders way back to create space in the middle.

I like that Ødegaard is increasing his responsibilities in the first phase, but this also shows some of the shortcomings of starting Trossard in the “left-8,” despite all his brilliance. It’s not necessarily about the defensive shape, as Rice has proven he could probably start behind two u15 Hale Enders in the midfield and make do when out-of-possession. It’s more about optionality in build-up.

Trossard offers good “jail-breaking” carrying when he drops deep, but can be a little herky-jerky in first-phase passing. His medium-length passes can (somewhat oddly) lack the appropriate weight. That can be overcome, as Havertz isn’t exactly Xhaka in these situations, either.

The difference is that in a scenario like the above, Havertz would offer a different outlet — the ability to play over the top of the press — whereas Trossard isn’t really additive there, either, despite being solid at picking up second balls.

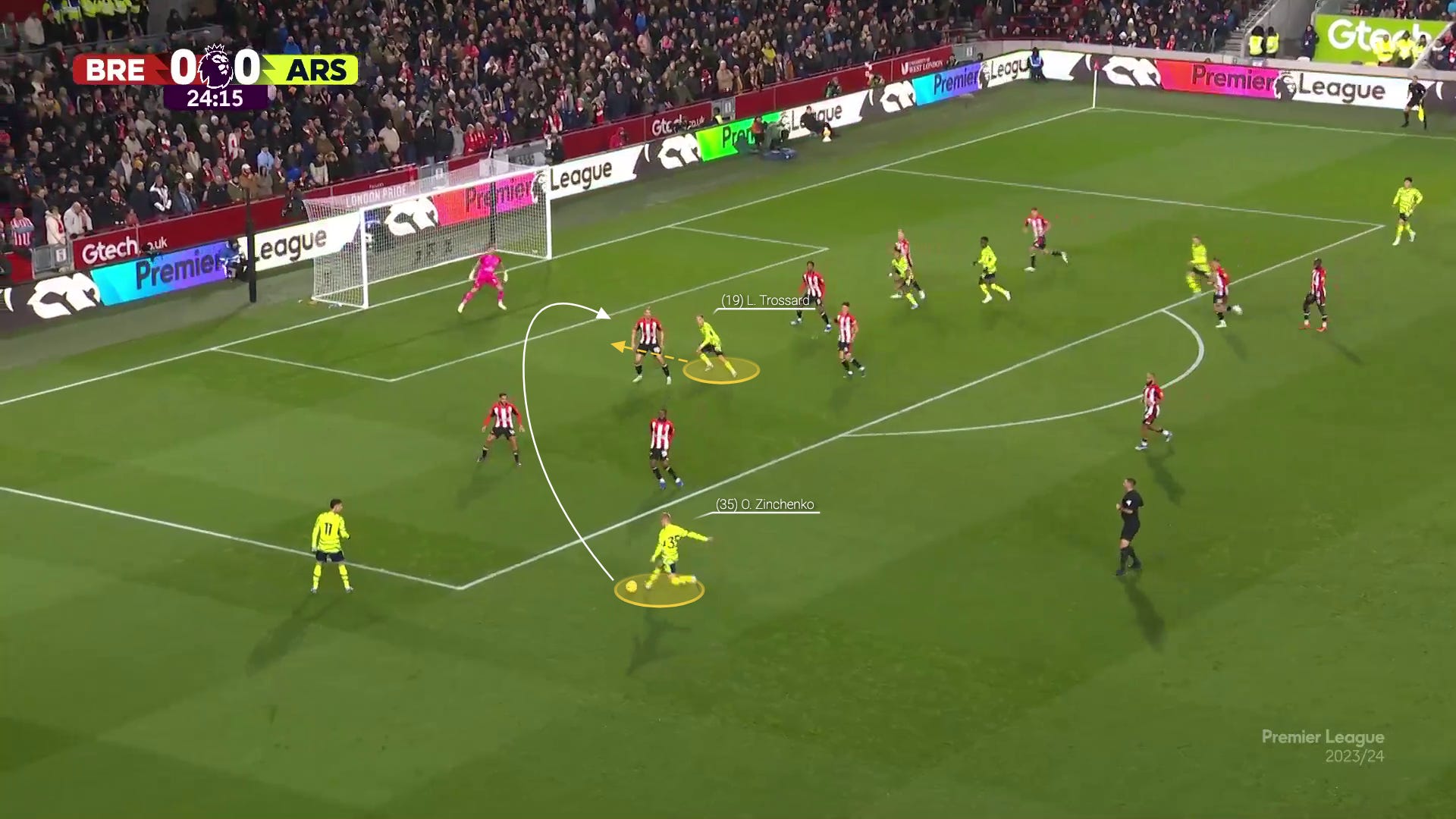

So if the opponent is cutting off Saliba, and the left-8 isn’t much of a build-up midfielder, the best option was probably to have Zinchenko cut through the press. Thanks to Ramsdale’s nerves, though, that couldn’t happen with the appropriate amount of polish. So then … you can go over the top to Jesus, who is always so scrappy and smart about coming down with the ball. The problem there? He was marked by Ethan Pinnock, who literally might be the last centre-back on Earth I’d want to face in those situations.

The result was stuff like this. Ramsdale would fling it forward at the first sign of bother, but Arsenal wouldn’t have a compelling philosophy for winning the situation. Pinnock was draped on Jesus, a 6’6” Ajer could patrol the area in front of him, Mee would even be further back, and no joy was to be found. A couple of times, this would lead to a quick-break for Brentford the other way.

Compare that to the long passing of Raya against Lens, who had the advantage of Havertz starting over Trossard, and some shorter defenders to target. He went 14/17 on long-passes alone on the day.

With Raya joining as a card-carrying member of the build-up squad, plus so many Arsenal players flooding the deeper areas, there is a problem for the opposition — especially if they respect Raya’s role as an actual “+1.” There are simply too many people to cover.

In the lead-up to the third goal, you’ll see that here. There aren’t sufficient numbers to press:

…and because of how many players are low for Arsenal, and because Ødegaard is floating around the middle, and because Havertz is an aerial threat worth tracking, Lens is left with bad choices. As a result, their dominator centre-back — Kevin Danso — had to pull all the way up past the halfline to keep an eye on the two Arsenal attacking midfielders.

As soon as that happened, Raya saw that he could play over the top.

What’s left is Martinelli facing an even fight against a 5’11 defender (Jonathan Gradit) who is 25th percentile at aerials won. Danso has to try and get back into position, but Havertz wins the second ball, as he does so often.

…and here’s where, yes, Havertz is getting better. I’m not among those who believe that Havertz is playing the same and the team is just using him more effectively. Here’s a quick example. As soon as he won the ball, he pushed forward, which hasn’t happened consistently. But the pass is where things are really improving. All year, he’s been angling these for maximum safety instead of maximum danger. A few weeks back, he’d probably play this a touch behind Martinelli, or out wide, to make sure that the ball isn’t lost. This time he rolled it out and let him run.

And when it comes time for Martinelli to shoot, there are gaps in the line, and the guy who would probably clean this up — Danso — is not back yet. The ball ricochets and Saka chests it in.

A few changes — Raya being excellent, a floating Ødegaard (Floategaard?), Havertz being in — have compounding effects.

👉 The final third

So I’d make the case that the Brentford game had different characteristics than those that preceded it. Since Chelsea, there has been some more dynamism and diversity in the build-up play, and Arsenal have generally done a good job of moving around the block. On the other hand, the final passes and movements have been comparatively less consistent.

Against Brentford, I watched back, and thought: this is the opposite. Arsenal still dominated possession and had plenty of the ball in advanced areas, but because they skipped sequences to do it, the block wasn’t sufficiently tested or moved around. Brentford were able to sit comfortably in their zones.

Still, I’d usually sit here in my typin’ chair, pop on my hindsight goggles, and list off the things they should have done differently in attack. But there’s one problem. Arsenal pretty much did them all. I loved most of what I saw structurally in the final third.

Central progression, you say?

Saliba read your articles and thought, “I’ll do it myself.”

Martinelli was at his marauding best, poking the block for vulnerabilities. Jesus and Fast Gabi looked like they were back with the national team, playing relationist Dinizball.

(If you’re wondering my personal philosophy, which you aren’t: I prefer pure Pep positional discipline in the build-up; then 2-3 central areas that are always filled, without exception, in the advanced “rest” shape; and then pure Ancelotti in the final third. If you have good, smart players, let them fuckin’ express themselves.)

There was another item that we were clamoring to see more, as you’ve read over and over here: the purposeful cross.

👉 Feeling cross

All crosses are not created equal. I’ve never been a big fan of the super-wide, head-down, spray-and-pray cross from a full-back — mainly, because it has a low chance of success, and also takes the full-back out of transition defending.

There are better options. Two come to mind: the cut-back cross after an overlap, and the half-space whip.

Against Burnley, Wyscout tallied 24 crosses for Arsenal. Against Brentford, the number was 21. These are both well over the season average. As you’ll see, a lot of them came from Martinelli.

Arsenal’s whipped crosses, and the timing of the corresponding runs, were generally very, very good against Brentford. A lot of the best chances of the contest came on plays like this.

Or this.

Here was the goal that was offside by an inch or so.

Here was an annoying moment. Ødegaard raised his hand for the deep cross, and Martinelli cut back, and delivered a perfect whipping ball — but Ødegaard never went for it. Brentford let it bounce over the endline.

I include that one not to slander Ødegaard — TAKE THAT SHIT ELSEWHERE, THANK YOU — but to reiterate something else. When you hear stat people talk about “expected goals,” “expected assists,” “key passes,” or “chances created,” please remember that those are all shot-based metrics. Meaning, they require a shot to occur. So if you fire in a perfect cross, but nobody connects with it, it’s worth zero across the board. I’d posit that part of our issues with “chance creation” are actually a problem with nobody getting on the end of some of these balls.

So why did none of those wind up in a goal? I know I can be a bit nerdy, so I hope this is not too complicated: Brentford are very big and our lineup was not very big at all.

With that quality of cross, it should be no surprise, then, that Arsenal would score shortly after subbing on our Tall Boy Midfielder. Boom.

As we’ve covered, you generally want a majority of your guys (if not more) being tall and good in the air, because there is an equilibrium to strike on set pieces and opportunities like this. Arsenal certainly have the raw materials to do that, as they showed in the second half against Lens with a lineup of Ents. While I have no problem with using some smaller guys to unlock a big foe, there was not enough of a cohesive attacking identity against Brentford. If you’re going to go long and pound in crosses, get a big lad up there.

Which brings us to our next point.

👉 Our large adult midfielder

Readers, I think it might be happening.

Here’s what we wrote after Havertz paid a big role in the leveler at Stamford Bridge:

TL;DR: Let’s kick it to Kai’s head a whole lot more and see what happens. This can be at striker, sure. But Saturday showed what I’ve been yelling all year: if he starts at “left-8,” there is no reason Havertz can’t just rotate up to be the aerial target with Jesus falling in behind. This turns him into the unicorn he potentially is.

In terms of positioning, something interesting about Havertz is that he excels at link-up play while leaning a little right, but seems to be a clearly-better finisher in his home left pocket.

In his career, he’s played a lot more on the right, and has rarely scored from over there. Here are his career goals — you’ll see a little gap on the right:

Which brings me to my final point on this one: I see little reason that Ødegaard and Saka shouldn’t just be spamming 4-5 far-post crosses to Havertz a game. We’ve barely seen it at all, and to my simple mind, it looks like money laying on the ground.

But it hasn’t all been smooth sailing. Despite immediately becoming our Joelinton out-of-possession, there have been moments of hesitation that have put him on the wrong end of narrow margins. On top of that, teammates have missed his good runs.

In a recent newsletter, I laid out my theory of the case in a section called “Kai Havertz, rethinker.” In it, I showed a bunch of examples of the “Havertz Hitch,” in which he makes the right run, then wavers.

Many footballers have to work on improving their instincts, forcing their learned attributes to become more immediate. Havertz does not have that problem. His basic football instincts are pristine, sublime, near-perfect, which is why so many coaches love him.

The problem? He’s a rethinker.

We can all speculate why, from his weird time at Chelsea, to a new system here, to a growth spurt. But what you see on the tape over and over is a player who is regularly doing the right thing and then, given a second to think, accumulates a little doubt.

Look closely at the difference between Martinelli and Havertz — a confident attacker and one who is less-so. They make the same read at the same time, and Martinelli sprints the whole time; Havertz runs, then re-thinks and feels it out, then runs again; this is probably a few inches away from a possible goal.

But if you see all these situations, and can delete the moment’s hesitation from the middle of them, you have something unique.

He didn’t hesitate on the winner against Brentford.

Against Newcastle, he didn’t look particularly hesitant when turning and driving forward — which is a tangible way he can be better than Xhaka was, if this confidence persists.

And he didn’t look hesitant in the second half, generating this chance out of thin air.

In all, you’ll see a player that was acting then acting, instead of acting then thinking. He made 63 actions overall, and you’ll see them all over the pitch:

This included 27/27 passing (100%), 4 interceptions, 5 recoveries, and 25 duels overall. He wound up being named Man of the Match.

Most promisingly, this continued a trend of him getting more involved. It’s a similar amount of activity to what he did against Brentford, Burnley, Sevilla and Newcastle.

Do I expect there to be ups and downs in the future? Sure. Here’s what he had to say.

“Nowadays, everyone just looks at their phone and see a goal and an assist. If not, I don't know, he played bad. I think football is about a lot more than only this (goal and assist). I don't put much pressure on myself by this.”

I think it’s fine to expect goals from him, given his role. The good news is that, on top of everything else, they’re starting to rain.

👉 Fløategaard

Ødegaard has had a bit of a weird year. Many things are afoot. He’s battled injury. He’s generally been shadow-marked by big defensive midfielders in an attempt to deny him the ball, as other links are less frightening to the opposition. He’s developing new relationships on the pitch.

But even so, it’s fair to say the season hasn’t quite lived up to the captain’s own expectations.

While I say that, we can also say that this is not exactly a crisis.

One of the interesting parts of the season is that Ødegaard’s role has generally been less straightforward. Where he used to reliably park in the right pocket and orchestrate play, he’s simultaneously become more of a goal-hound and more of a deep build-up option, as we saw in earlier screenshots.

What has happened thus far is that, with the middle of the park so jam-packed, Ødegaard has swayed out a little wider, vacating the central areas. See the below from The Analyst:

In a season when many would expect his chance creation to go up, he’s only been credited with one assist so far.

While he appears to be playing himself back into fitness, and hasn’t been his fluent best quite yet, there are signs of life. In the last two games, Declan Rice and Ødegaard have traded 31 total passes.

Against Brentford’s block, Ødegaard stuck in the right pocket more. But against Lens, his play was a lot more expansive, as you’ll see by his “received passes” map below.

In that one, Ødegaard could be a lot more interactive with more players, and more rotations were unlocked throughout. It was made a bit easier with Lens pressuring as they did, but especially with Havertz on the pitch, I see few down-sides to Ødegaard freeing himself from the half-space and getting more involved elsewhere.

OK, let’s wrap things up.

👉 Loose thoughts

♦️ Flowers for Gabriel and Tomiyasu

Here’s a masterclass in wide, “side-on” defending. Mbeumo is a tough mark in this type of situation, and Gabriel did everything right — low, aggressive, crowding space, stepping in at the right time, drawing a foul.

He’s been close to faultless for over a year now, and our eyes shouldn’t adjust to the nice horizon.

Meanwhile, Tomiyasu offered everything from sprinty overlaps, to bursting carries, to stable defending, to adding all kinds of passes along the way: the half-space cross that resulted in the opening goal, the one-touch blast out to Martinelli that led to another, the cut-back for the Ødegaard banger. He did this all in one half.

After knee surgery in the spring, I’m not sure any player has surpassed my expectations more. My thoughts on him have evolved through a few stages:

“He’s got 90% of what I’d like in a full-back, but 100% of the tools of a centre-back. I wish Arteta would give him more time there.”

“Actually, now he looks most comfortable as Big Timber, floating and expressing himself as a left-back. In fact, I think he looks even better there than on the right, where his overlaps haven’t turned into enough output.”

“………….Tomi should play wherever the fuck he wants.”

I think I’ll stop pontificating and just enjoy the show.

♦️ Diamonds are forever

With White and Kiwior entering for the second half, the lineup got well and truly Big, and immensely Champions Leaguey. From my vantage point, Kiwior is playing himself into more meaningful time, and his development path has been quicker than I expected; he’s now worthy of Premier League starts in three positions.

Here’s three big CB’s behind a diamond midfield containing Rice, Kiwior, and Havertz. This is Big Boy Football.

♦️ The wingers

You all saw the highlights and I have little to add. What I will say is that I think Saka is getting better as a defender every week. His dueling style is more proactive and effective at winning the ball, and the stats bare it out.

He is leading the Champions League in goal contributions, and no, I’m not all that concerned about how he’s being supported tactically right now. I’ve shared my spiels before on how, especially against low blocks, the team can likely afford a more parked bonus winger at right-back (think a Frimpong type), but that’s a discussion for another time. Saka is doing just fine, thank you.

I’m not fully certain why this wasn’t an assist, frankly. Ridiculous stuff.

(Edit — this did get credited as an assist in the end. Wasn’t showing up initially on my side, and some services still aren’t giving it)

On Martinelli, we were all reminded of what a perfect character he is for the Champions League, and how effective he can be when given space. It’s an odd request, but I’d like to find ways of helping him be lazier in the block, so that he can cheat up the pitch like Vinicius does, and Ronaldo once did. Opponents should know that whenever they’re attacking, they’re one long-ball away from pain.

♦️ The shape of the block

Just a quick note. The last two games have seen a return of the 4-1-4-1 block, with Rice at the base. This is something I was clamoring for when there were defensive struggles in the preseason. It’s nice to see it working so well.

In short, this makes certain that Rice is always on the ball-side (but not pulled out all the way to the touchline, as he may be in a 4-4-2), that here is always ample pressure (with Havertz and Ødegaard jumping when the ball is near), and that it’s harder to complete switches. The more unavoidable Rice is, the better.

♦️ Final thoughts

I don’t know how I’m supposed to wrap this up. Declan Rice and William Saliba are good? Gabriel Jesus is an undercelebrated genius? Mikel Arteta has nice hair and a big brain?

In general, I think there is much room for optimism at the moment. There will undoubtedly be bends in the weeks to come, but one can find solace in the step-by-step improvements in the campaign thus far. In the pre-season, new additions were eased in, and out-of-possession issues were hammered through. From there, build-up dynamics have generally improved. Next, the attack is gaining more vibrancy, and crucially, Kai Havertz is gaining steam. The next step could feasibly include an improving Jakub Kiwior, injury returnees, and a potential January addition.

We know the next steps will be difficult, and other teams will continue to adjust to everything we’ve covered here. Mikel Arteta is not the only smart manager with good players. And in the short-term: man, do Wolves and Gary O'Neil look tough.

But in the longer-term, if Dylan taught us that “we can’t come back all the way,” maybe that’s a good thing. Maybe something different is afoot.

Thanks so much, you’ve quickly become my favourite long form read on The Arsenal

Fantastic article as ever Billy, good to see Lens’ tight defensive performances since we last played them highlighted. Seen little mention of it elsewhere.