Scouting Martín Zubimendi

A massive profile on Arsenal's likely midfield signing: his fit, function, defensive game, physical profile, press resistance, passing range, untapped skills, and potential to transform Arsenal

“No, there’s nothin’ you can send me, my own true love

There’s nothin’ I wish to be ownin’

Just carry yourself back to me unspoiled

From across that lonesome ocean.”

— Bob Dylan

In Thief (1981), James Caan’s character, Frank, is seen breaking into high-end vaults during a spate of nighttime heists. These scenes are not edited for pace or drama, and there’s little dialogue. Everything looks disarmingly practical. Michael Mann lets it play out slowly, clinically, as we hear the grind of the machinery and the hums of the power drills.

Our man Frank isn’t improvising. And Caan isn’t using movie props, but actual tools: a magnetic drill press, an industrial torch, and a custom-built thermal lance. The camera lingers as he locks the press into place, adjusts the angle, and begins boring into the safe’s reinforced steel. Sparks fly, and there are no dramatic cutaways or bouts with cheap tension. Just a man doing his job.

Screenwriters have a phrase for this kind of scene: “competence porn.” It’s meant to describe the appeal of watching people who are good at what they do, especially when it’s complicated, and especially when they do it with precision and calm.

It’s part of why we’re willing to watch Matt Damon read manuals, rig parts together, and shovel shit in The Martian. It’s part of why Hidden Figures and Arrival resonate, or why we watch Sherlock Holmes solve problems we don’t fully understand. The satisfaction is from the stakes, sure, but also … we like watching capable hands. We like watching systems being worked, problems being solved, little mechanics of confusing jobs being revealed by people who make them look easy.

It’s also why people like watching Martín Zubimendi.

We’ve spent a lot of time in Basque Country.

Last summer, we profiled Mikel Merino. We began with his winning goal in the Euro quarter-finals, when he pointed his points, scanned his scans, ghosted into the box, and leapt to head home the winner.

In the final itself, Merino came on late, but two other Basques had more decisive roles. Mikel Oyarzabal scored the winner in the 89th minute, and Zubimendi was subbed on at half-time — replacing Rodri, the Ballon d’Or to-be, who’d gone down with a hamstring issue.

Spain didn’t miss a beat. Zubimendi had 32 touches, completed 92% of his passes, made three recoveries, and won all five of his duels. The team scored twice in the second half and lifted the trophy.

Spain head coach Luis de la Fuente went right to the top shelf for his praise.

“We already know that Martin is a sure bet. He always plays very calmly, very quietly, always with great judgement … Martin gives you everything you ask of him and has fantastic talent … He's a great player. For me, as I've already said, he's the second-best player in the world, along with Rodri.”

Presumably he was talking about the position. And perhaps … a little strong. But his club manager, Imanol Alguacil, put it likewise:

“We’re talking about one of the best, not just in Spain but in Europe. There’s nobody really like him. Even when he’s just below his best, you notice it. He’s a very hard player to replace.”

Zubimendi is a product of Real Sociedad’s famed Zubieta academy. When we profiled Roberto Olabe as a potential sporting director candidate, we dove into the little idiosyncrasies that make Zubieta so special — and players like Zubimendi so loyal. It started with an excerpt from an ESPN profile:

“That process starts at 13, which is late compared with many clubs. Iriarte is a qualified teacher, something he shares with around 60% of the staff in the academy -- schooling is part of the process, and their approach is integrated with the educational policy of the Guipuzcoa government. That means there's no push for specialisation or professionalisation early; kids are instead expected to participate in many sports. Real Sociedad don't sign players earlier, and they don't shed them early either: there is no annual “cull,” and they commit to keeping every player for at least the first two years. To playing them, too: the focus is more on development than recruitment, keeping turnover low.”

It’s a refreshing view.

“Are we 100% certain that all the PE teachers are doing things well?” said Academy Director Luki Iriarte to Cano Football. “No. But we know that the kid that’s coming here at 12-years-old has played handball, basketball, done cycling and many other sports. We believe that all this helps us to have an open-minded, more flexible individual.”

Zubimendi broke into the first team in 2019 and quickly became central to their midfield. By the 2020/21 season, he was a regular starter, helping La Real win the 2020 Copa del Rey — their first major trophy in over 30 years.

He’s made over 175 appearances for the club, anchored their return to the Champions League, and earned 17 caps for Spain. He’s won both the UEFA Nations League and Euro 2024, and often gets floated as Sergio Busquets’ heir.

Zubimendi is flattered by the comparisons, but notes the differences, too.

“For any pivot, Busquets has been the benchmark in recent years, and will be for many years to come. By comparing me with Busquets, anyone would lose out. We share a position, but at the same time we are very different. Busquets is the best at what he does. In my own way I will try to make my own way, comparisons may be there but I don't focus on them.”

He’s been the apple of the eye of so many of Europe’s top clubs, and turned all potential suitors down. Now, it appears he’s said yes to Arsenal. We’ve even received the ceremonial Ornbombs and Here We Goes.

Many are thrilled at the thought of landing such a revered midfielder. Others are wondering how many of the club’s big questions he can answer on his own. Is he a ceiling-raiser, or a floor-holder?

Let’s dig in.

📖 Player overview

➡️ Role and playing experience

There’s a reason for Arsenal’s infatuation with Real Sociedad players.

Outside of the Premier League, at least, there are few better places for Arsenal to receive a player from than San Sebastián. Though they were simply undertalented this year — the churn of players from Mikel Merino to Robin Le Normand was just too much for a club that doesn’t splurge on big signings, and they didn’t nail their incomings — they’ve always employed a thoroughly modern, aggressive, often fun style of football, and they do it regardless of opponent. In Imanol Alguacil, who is wrapping up his tenure this spring, they’ve had a steady source of instruction and tactics.

In many ways, they play like a more plucky, more direct, more impatient, even higher-pressing Arsenal. They even throw in the focus on duels for good measure. Martín Zubimendi has been the fulcrum.

What’ll strike you is just how lonely this iteration of the lone-6 is. Whereas most current Premier League teams — including Arsenal — drop someone into this pivot during build-up, Zubimendi is all alone. The full-backs don’t invert, and the two 8s only drop down in moments.

This leads to something fairly unique in Zubimendi’s remit. He is constantly moving, scanning, and setting up angles, but as a lone-6, he’s not always over-eager to get on the ball or looking to rack up 100 touches. He’s more situational and flexible; he’s talked in interviews about how sometimes he thinks he should get on the ball more, before remembering his responsibilities in his setup.

Because he’s usually outnumbered by pressers, he’s often dragging them away from the 8s, creating lanes, and freeing them up to turn and attack. If the press has gaps or is more mindful of the 8s, he pulls all the strings himself and is happy to drop all the way down and split the centre-backs if needed. If there are numbers high, he pulls the pressers and they go long as pounces for second balls.

Last year, I investigated why Real Sociedad’s progressive numbers were lower than one might expect, given that they play such a seemingly modern style. What I found then:

Real Sociedad have the highest line in LaLiga, very disruptive to opponent build-up, lot of mid-to-high wins and loose balls = no progression needed

58.3% of goal-kicks launched (hence Merino aerials) = progression is skipped

Zubimendi is content in the 'cover shadow' dragging players around, creating space for others

As a result, deep circulation is split between four different defenders, three midfielders, and a GK. The numbers get spread out; not a lot of stat-padding to be done

When he does rack up touches, he’s perfectly comfortable. I’ve seen him log 100+ passes in his younger days, with u21s, or in a 2023 Euro qualifier against Cyprus. Here, he went 77/81 (95%) against Serbia in October.

So much of a player’s touch quantity is informed by the system and the player’s responsibilities. But you don’t want to neatly explain everything away, and there is definitely an archetype of a lone-6 that says, usually with ample reason, “just give me the fucking ball. I’ll figure this out.” Zubimendi appears humbler than that.

You can see how it often looks like a 4-1-5 as it progresses:

Here’s a wider example of just how “lone” he can be between the lines:

But that isn’t the only team he plays for.

In fact, I felt like I learned more by watching a game or two of his work on the Spanish team than I did in 10+ at Real Sociedad. Because he’s been in such a stable position and environment at his club for so long, it’s been interesting to see him under the guidance of Luis de la Fuente in Rodri’s absence.

He serves as the deeper member of a double-pivot, which turns more lone-6y as things progress. His swirling relationship with Fabián Ruiz is a joy to watch, and he’s freed to push up a bit more as well. He’ll carry a bit more; I even saw him dive into the middle to head a cross.

It shows that he’s not only a pure, lone-6 even if that’s been most of his responsibility at the club level. Save that for later.

The La Real press has a lot of similarities to what Arsenal do. It’s aggressive, often man-to-man, and usually features a three-man “door hinge” up top, where Merino used to roll. Zubimendi’s job is to enable all that upfield pressing by manning the fort below, moving laterally to support everything in front of him — often touchline to touchline. He does a good job, and pressing involves accountability. You can jump that split-second earlier if you know, 100%, that the person behind you is doing their job.

Here’s another view of that responsibility:

The team doesn’t usually fall back into a more typical block, but when it does, it often looks like an Arsenal-friendly 4-4-2:

Meanwhile, he doesn’t have much experience at higher levels in that #8 role. I have seen scattered hints that he came up as a #8, though perfectly-sourced confirmation is elusive. I barely want to mention this out of embarrassment: I went as far as looking up his squad numbers in his youth sides, and they would seem to indicate a more advanced midfielder; there is a #8 and a #14 in his history. It makes sense if so.

In short, there is always an adaptation period, but he is well-prepared as one could hope for the responsibilities of an Arsenal #6, and looks comfortable as the deeper man in a double-pivot. A longer, more stable preseason would help a lot.

👉 Physical overview

At 5’11”, Zubimendi has a standard-issue build for a central midfielder. On first glance, and even with a few watches under your belt, he seems like a perfectly capable but unexceptional physical presence: not too big, not undersized, not too fast, not too slow. But while the Premier League is getting more physical and intense every year, football athleticism is more than meets the eye. Weird nuances are everywhere.

Players like Declan Rice or Eduardo Camavinga announce their springy athleticism for all to see. It doesn’t take much to understand what makes them different, and rightly so. But for others — Busquets, Gündoğan, Jorginho, Fabinho, Rodri types — we have to acknowledge that football athleticism can be a unique, complex thing. As an analogy of the day: the world’s best basketball player cannot really jump.

Speed and size are important, but there are other factors. That means looking at some of the nerdier categories: body control, balance, movement efficiency, load tolerance, and some other buzzy phrases.

As a pure runner, Zubimendi is about average. He’s not a high-knee sprinter, but uses shorter, tighter strides that let him change direction quickly, which is handy in crowded midfield spaces. The effort is always there, but over longer recovery sprints his pace is merely fine, and that’s not something you can fully discount, as it’s getting more important every year. It’s one of the biggest risks of the whole signing.

To be clear, though, he’s no Jorginho. While top speed isn’t the most useful or reliable metric, he hit the same top speed in the Champions League last season as Bruno Guimarães and Joshua Kimmich — 31.8 km/h. That sounds about right.

Here’s him on Kluivert the Younger.

If he can get “touch-close” on you, he can usually slow you down. I was specifically looking for times he had to run against Premier League or Champions League competition. Here’s him on Rashford.

His objective is to avoid those long-sprint situations. As I looked for those clips, with suspicion in my heart, what struck me was how few of them there were to watch. He’s a great counter-presser and prefers to interrupt things at the source.

He’s a pretty clean decelerator and doesn’t often over-commit or skid past his man, though I’ve seen it happen, and tricky types can occasionally beat him on side-to-side agility, which he seeks to counteract with repeat intensity. These come every so often, but the efficiency stats stay high:

His little shuffle steps and upright positioning generally serve him well. There’s a slight hint of stiffness to his actions, but while he’s not as bulky as a Rodri, I reckon he’s a little quicker. It’s close.

Physically, he stands out in two areas: core strength and balance. He shows more discretion than chippy tacklers like Merino, Ugarte, or Mac Allister. When opponents try to lean into him, though, they rarely win the balance battle. More often, he’s already won it with a quick hand-check, a subtle weight shift, or one of those veteran tricks. If there’s one quality that links Hale End talents like Saka, Lewis-Skelly, and Nwaneri, it’s this: they’re almost always the ones with the balance in a 1v1. Zubimendi has that; there’s just a steadiness to him. He doesn’t go to ground unless he has to.

While not a towering presence, he offers a training video on how to win leverage before aerial duels. This leads to a high, well-earned success rate that will translate just about anywhere, though he’s not a big influence on attacking set plays. I’ve found that aerial duels are one of the trickier traits for a player to improve. There’s just something innate there. He’s got it.

His natural fitness and work-rate are strengths. His effort and application don’t ebb and flow based on the minute or the schedule. He rarely misses time; yes, having a body that can do The Thing without breaking down is part of a player’s athletic makeup. If a fast player gets injured every time he runs fast, is he actually fast at all?

He’s got a good weaker left foot, and uses it often to help him resist the press or hit through-balls. He’s snappy, deceptively agile, and coordinated on the dribble.

In general, his physical baseline is adept, nuanced, and subtly interesting — though not in the highest tier. While he doesn’t wow you with his gifts, he’s no slouch, and is an efficient, strong, balanced athlete, and has proven himself against top players.

🧠 Playing temperament

As with Merino, there isn’t a lot of nuance to this section. Zubimendi is one of the smartest players around. Coaches adore him because it’s the closest they’ll get to being back on the pitch. If you want to feel confident about a midfielder’s abilities to orchestrate and command your team from deep, there aren’t five better options.

Here’s him stripping Barcelona, driving forward, and assisting with his left. A showcase of all of his sharpest skills:

He plays with a distinct sense of calm, rarely getting too high or too low; I’ve virtually never seen him particularly frustrated, exuberant, or down on himself. His temperament can be described as cool-headed and team-oriented. In interviews, he comes off as cheerful, intellectual, and warm.

When asked what makes a good defensive midfielder, Zubimendi gave emphasis to the group:

“The first thing is the collective — not being individualistic. It’s about constantly helping, whether it’s for the defensive line or your teammates higher up.”

That’s where he sits: part facilitator, part protector, and always focused on the team’s shape and overall needs. He’s not a shouter or an emotional rollercoaster; he leads by example with his positioning and decision-making.

His disciplinary record is also good, rarely making rash challenges or getting into altercations. His fouls committed rate (about 1.3 fouls per 90) is moderate to low; he will take a tactical foul when necessary to stop a dangerous break, but he’s not one to dive into unnecessary tackles (though there’s a risk of lunging more in the Premier League). In the weird world of La Liga refereeing, he’s never a target of ire.

His mentality in big games has been a big positive. Stepping in for a Ballon d'Or winner in a Euro final at halftime for Spain, he probably improved on his normal levels. He hasn’t been stranger to pressure elsewhere (Copa del Rey final, Champions League deciders, Basque derbies), and Zubimendi seems unbothered by big atmospheres or high stakes. If anything, he clarifies his game even more in those moments.

His sense of anticipation puts him among the world’s best, and makes him one of the players I enjoy watching the most (he was the starting DM in my “Turn on the Television XI” in September 2023). If you see a play where he does something simple, like cutting a passing lane, it’s fun to go back and rewind: without fail, he’d anticipated the chain of moves 10-20 seconds earlier and situated himself accordingly. You can learn a lot about reading the game from watching him.

We’ll get into the tempo side in a bit, but that’s another thing Arsenal fans may like to hear: his calmer vibe doesn’t mean he tries to slow play down at all costs. He can play with real physicality and urgency if the game-state requires.

He comes with a long list of character references in Merino, Ødegaard, Tierney, Raya, and others. I wouldn’t expect him to be a vocal cheerleader or an enforcer who fires up the crowd with big moments. Think of him as a force for quiet stability and equilibrium.

🧾 Showing my work

I like Real Sociedad and always try to keep up with them, so he’s been on my radar for a long time. I also watched a lot of matches for the Merino and Olabe newsletters.

For this piece, I watched/re-watched the Euro final against England, PSG (2023/24), Manchester United (2024/25), Barcelona (2024/25), Netherlands (March 2025), Valencia (2024), Union Berlin (2024), Real Oviedo B (2019), Ajax (Europa League), Lazio (Europa League), Nice (Europa League), Inter (2023), Benfica (2023), Denmark (2024).

After that, I compiled a 225-clip playlist of his passes, duels, recoveries, shots, dribbles, carries, ball losses, and transitions. This helped me try to re-learn a player I thought I already knew — which has its own kind of difficulty.

➡️ Previous ranks

Zubimendi has shown up in my Arsenal models for over three years.

In January 2023, he placed 5th in the original D.U.E.L.S. rankings, looking for a deeper midfielder. I’ve highlighted some other selections there:

That November, he was 6th in the P.W.R. (Pair With Rice) rankings, which sought a 6/8 hybrid-type player who was good on the ball.

➡️ My priors

I like him a lot. He’s one of those guys where you always come away feeling like you learned something — very subtle, very selfless. People underestimate how rare and hard it is to play the lone deep midfield role in a team like this. Only a few players anywhere can do it, and even fewer are available.

Here’s what I wrote back then when evaluating him for a hybrid role:

Every time something happens, he’s already taken three steps in that direction. His feel for the game can border on creepy. Xavi agrees: “Zubimendi is an extraordinary pivot. He dominates the game, the moments with and without the ball. He wins duels, he is an extraordinary player in that position. He understands the model we like at Barça.” He’s a little lower than the others here because of their numbers up the pitch (passes into the penalty area, key passes, etc). Zubimendi is brilliant at driving tempo and pinging balls throughout, and I think a Rice/Zubimendi partnership would go brilliantly, but he’s also not necessarily the unsettling dribbler or final-passer that the team feels light on right now, and I find his temperament on the pitch (which can always change) to be that of a true pivot. Put better: I reckon he’s more Partey’s replacement than Xhaka’s. As such, a Zubimendi signing may commit Rice’s future to the #8, and there would be risks of more 1-0 and 1-1 type games if the final action never comes. That, and he doesn’t seem to want to leave San Sebastián — which, fair. Slim chance normally, almost-zero chance during a promising UCL campaign.

I used to call him “Mensa Mac Allister,” which doesn’t make sense because Mac Allister is plenty smart, but that gives you a sense of how I see him.

We’ve also written in the past about how comps, all-action reels, and highlight packages can have a natural bias towards certain players and against others. Zubimendi is a prototypical “watch the full-90” type.

My only question with this signing is that I worry that a Rice/Zubimendi/Ødegaard midfield is a little light on indefensible killer balls, and am always hugely intrigued by Wharton types for that; Bruno Guimarães always struck me as the right balance, but alas, fuck Bruno Guimarães. Zubimendi doesn’t necessarily offer that on his own — he’s more about enabling others, drawing pressure, timing things right. I think an acquisition of his profile would raise the bar in another signing (say LW) to be able to provide some nasty crosses, or else we’re a little too reliant on Saka again.

Watching him even more reinforced some of these preconceptions, but it also expanded and challenged others.

📊 Statistical overview

Here’s a big comparison of Zubimendi with Arsenal’s current defensive midfielders. I also threw in two of the younger, “Premier League proven” options I’d be most interested in.

What stands out?

I think it’d be fair to say he has the most efficient defensive record of the group, even if it’s partially due to the amount of firefighting he’s had to do this year. Still, everything he does out-of-possession is high-percentage.

His stats up the pitch (deep completions, shots, passes to the penalty area) are among the most limited. He generally touches the ball less up there.

His touches don’t seem particularly low here. Higher than Rice, lower than Partey/Jorginho.

Interestingly, he matches Partey’s forward passing on fewer touches.

His short passing % is lower than the current Arsenal men. Everything is a little more direct.

His 3.38 “own half losses per 90” are worth investigating. To be clear, a missed pass is a “loss,” so if somebody blasts a long-ball over the top, it shows up here.

…and here’s a defensive midfielder template:

There are some other interesting tidbits in there, but onward we go.

👉 In-Possession

➡️ Passing and receiving: Small, tempo, build-up, progression

Here’s what he learned from working with Xabi Alonso:

“With him, I learned to recognise and differentiate [types of] presses, overcoming them. Before then, I played the way that more or less came naturally. With him I started to truly understand concepts for bringing the ball out, building play. He insisted a lot on the analysis. We would walk it through, inflatables positioned where the opposition would be.”

He’s been compared to Busquets a bit, even though they carry a lot of differences. Here are his thoughts:

“Busquets is unique, so good at feints, cutting back, very sharp, very clever pressing on the front foot, although it’s harder when he’s forced to go backwards,” he says. “Us pivotes have the bad luck that maybe we don’t get recognised but if you understand football you know Busquets’ value. We’ve normalised him playing well so much we don’t always appreciate him. He’s set the bar so high that pivots are asked to do things we weren’t before. But that’s nice: you have to aspire to that.”

Zubimendi’s deep work starts with his pre-processor. Before the ball arrives, he’s scanning, scanning, scanning, shifting, and setting up angles. He’s always trying to move around the opponent’s shape in whatever way he can, and not just through his own individual passes.

This shows up in his decision-making. Because he’s been planning his moves, he rarely has to overcomplicate things.

He shows care with the ball in deeper areas, and is always looking to provide helpful angles for teammates. Most of his deep passes are straightforward or deceptively simple, but they come quickly, often on the first touch, and usually with purpose.

There’s a lot of straightforward, deep stuff like this — with both feet.

He has serious pausa, and is often keeping it ticking and looking for gaps, and usually gets more expansive and interesting as things progress.

Here’s an example of how his focus is to “manipulate the press as much as possible,” and not “receive the ball from deep as much as possible.” After he’s joined in the pivot, he loops around, sees the jump by Barella, and then escapes behind him for a free carry.

He has a slight tendency to lean left in his movement patterns, but he shuttles horizontally all over the pitch, and is pretty comfortable passing anywhere. He also likes dropping in between the centre-backs. That positioning can open up more carrying lanes for them (specifically Saliba, and Calafiori if he plays there) and might involve Raya being able to stay a little deeper.

He’s confident deep. These are the little moves that Ryan Gravenberch has been doing that have changed Liverpool’s world.

He can receive under pressure and push forward.

In terms of body shape and balance, he’s strong. When he’s put in a spot of bother, or it’s time to turn or ride a challenge, he stays upright and snaps through his dribbles with good control. He’s hard to shift and keeps the ball moving.

His first touch usually sets him up well, though it’s not perfect or ultra-silky. Occasionally he’ll have to muscle it down or adjust on the fly.

One of the areas in which a taller DM has an advantage is when a teammate slightly mishits a pass and the player has to stick out a leg to retrieve it.

Given how often he’s recovering possession or involved in duels, he tends to play off his first touch to keep things flowing or force the issue. That probably explains some of the pass accuracy dings you’ll see in the data, which is a common theme at Real Sociedad, but there is a risk of some bounciness settling in.

Without watching them enough, you wouldn’t know just how many possessions start with tackle-passes like this:

Something Arsenal supporters will like, and which became more clear as I watched the “deeper cuts” of his tape, is that he feels more aggressive (and less concerned with pure security) against overmatched sides, taking risks while trying to push forward for goals.

In general, his clean, pragmatic build-up can suddenly be interrupted by aggressive passing up the middle, like this one to Olmo.

He adjusts to be more crisp and secure in games that require more patience. One example is the Champions League campaign from last year.

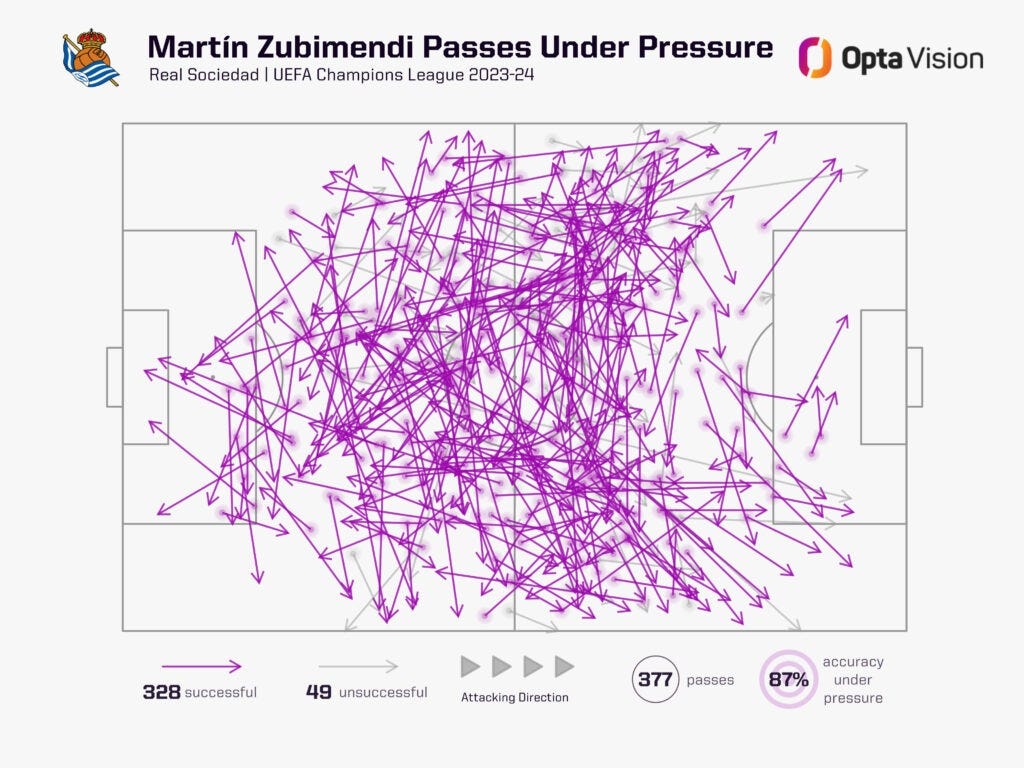

He completed 328 of his 377 passes under pressure in the Champions League last season (87%), higher than his overall pass accuracy in La Liga.

In short, Zubimendi gives Arsenal a prime midfield conductor. Arsenal have had that, but it has typically come with trade-offs: Ødegaard can do it, but it’s too far from the press; Zinchenko can do it, but he has defensive frailties; Jorginho can do it, but he’s aging and can get left behind in transition; Rice is a little too conservative; Partey is more one speed — he can turn and line-break at will, but doesn’t always modulate and de-risk based on game-state.

Zubimendi offers this ability, without as much cost. While he can’t quite spray it around like a Kroos or Jorginho, which would have been nice, he has a lot of that brain and desire.

With him on the pitch, Arsenal should find it easier to impose their preferred tempo on matches, whether that means calming things down (i.e., protecting leads) or ramping them up (i.e., when frustrated against mid-table sides) as needed. This is where he offers some real upside.

➡️ Long-balls, advanced passing, playmaking, and crossing

Zubimendi’s long passing stands out as simply “pretty good,” especially those switches out to the wing. He hits them clean, with purpose, and at a good tempo. He’s not just dumping it wide, not doing it too much, and not doing it for show — switches are often aesthetically pleasing but kinda pointless — he’s shifting the structure and opening up space. It’s a simple but effective way to stretch things in the right situation, but he doesn’t over-lean on it.

He doesn’t get into the final third much, which is mostly down to his role. He generally stays deeper, protects the back line, often alone, and focuses on controlling the tempo from behind the ball.

That said: when he does get forward, there’s a lot to like. In fact, this was probably my biggest takeaway from this whole exercise. I found myself loving almost every decision I saw him make up there.

There’s even some of the cute Ødegaard stuff.

And a few examples of left-sided pocket play, freeing runners up.

Here’s one of those bouncing balls that he flips into a looping through-ball on the first touch:

...and here’s the second phase of a set play, whipped in with his left:

He also has a few through balls in his locker. They usually come from deeper positions, just over halfway, and they’re more measured than flashy. He waits for the run, sees the gap, and times it well. They are often with his left:

Here’s another, with his left:

He doesn’t hit every one, but they usually have good odds to find their man. He’s definitely not high-volume with these, but when it’s on, I really like his decision-making and timing of release.

This all implies that he may have some untapped potential in more advanced areas.

In those mid-to-advanced areas, he can turn, take a touch under pressure, and play off minimal steps.

He passes with pace and confidence, usually keeping things on the ground. He’s more forward-thinking than one may suppose given his reputation as a pragmatic #6. It’s all usually sharp and consistent.

Two other notes:

Crossing isn’t part of his game. He rarely gets into those wide zones, and when he does, his instinct is to recycle. If he hits a wide delivery, it’s usually a cross-field switch, not a cross into the box.

He’s not going to rack up assists or float in set pieces from the deeper role. But there are some interesting details and bits of potential there.

It’s worth remembering how lone he is: Brais Méndez and Luka Sučić are often in more advanced positions, as was Merino, and the full-backs are wide and push forward. There just isn’t a lot of support for him should he push forward or take risks. With a little bit more of a cocoon — a pivot partner, a third “CB” behind him like Timber or White, not to mention midfielders who cover more — things could feasibly change.

➡️ Dribbling and carrying

This is another area where descriptions of Zubimendi as a steely pragmatist can fall short. It’s also where the Jorginho comparisons don’t jive.

Zubimendi is a snappy, low-key-muscular, generally impressive carrier of the ball. To me, this is where he’s most visibly impressive as an athlete.

It often comes out like this: he sees a gap in the middle, he lets it run, and he drives until he gets commitments.

We saw him in the final, flicking it past a Bellingham slide tackle.

More often, it looks like this: he navigates for a little space, and uses his hands to ride a challenge. Once again, the goal is to get a commitment so he can free up a teammate.

Jorginho may have a few more balls in his repertoire, but he’s going down there. (“Players are different!” he cries. “Comparisons aren’t panaceas!”)

He’s not in the highest end of quick agility, and can’t quite bend like a Kovačić, even though they sometimes look similar. But these little, pulsing, utilitarian carries have a lot of usefulness in practice, and can help attract defenders and start a domino effect in the opponent block. You’d like to see it more.

👉 Ball-striking + shooting

Zubimendi has nine career goals at club level, which tells you most of what you need to know. He’s not a regular goal contributor, and a big part of that comes down to where he plays, and how Real Sociedad play. While they do generally have high possession numbers, they don’t quite pin teams deep with long, patient spells around the box.

To put that in perspective: Zubimendi averages 8.06 touches per 90 in the attacking third. Rodri, by contrast, averaged 34.3 last season. That kind of territorial difference changes what you’re asked to do — Zubimendi simply isn’t often in positions to shoot. He averages just 0.59 shots per 90, and when he does shoot, it’s usually a one-off long ball or a recycled set piece. This is where he’s performed much closer to Jorginho than, say, Gündoğan.

That said, the goals he does have are a bit more fun than you’d expect.

He bent this one around on the first touch:

He shimmied and scored with his left foot off a late run:

He hit a one-touch volley off a corner (if you can make this out from the potato I recorded it on):

He even ripped one from outside the box that led to a goalkeeping error:

He strikes the ball fairly cleanly and keeps his head when the chance comes. It’s just rare that he finds himself in that kind of spot.

If you pushed him forward a bit more, I could see him chipping in with four or five goals a season in a well-functioning side. But I’d struggle to picture him hitting those 8-to-13 goal Gündoğan peaks without some serious evolution. He’s composed, sure, and hits a solid ball, but he’s not a reliably threatening scorer.

👉 Out-of-Possession

➡️ Anticipation & positioning

Zubimendi’s defensive game is a big part of his value proposition, but there is the aforementioned physical nuance.

He does his best work through positioning and anticipation. He’s the type to see danger before it develops, putting himself in the right spot to shut it down in seemingly simple ways.

This interruption of a counter is a good example.

He doesn’t chase, he makes slight adjustments and movements constantly, he waits, holds his zone, and makes the passing angles harder. This foundational role helps unlock a nastier upfield press, and leads to a lot of situations where he gets a leg on a cross-field pass.

A typical play looks something like this. He reads the play, contains it, and then starts leaning and getting physical.

➡️ Pressing

As we shared, he patrols the middle of the press, serving as the foundation for the forward jumps of the others. He’s rarely caught out of position, and is often the screener of the backline.

When he commits upward, he makes sure not to lose contact.

When he does engage, it’s almost always a high-percentage affair.

It’s rare that he actually gets dribbled past. This year, it’s 0.49 times per 90.

One of his best qualities is counter-pressing and keeping it pinned, which relies on that anticipation. You can see how dogged he can be here.

His fouls are on the low side, he doesn’t get baited into rash challenges, and wins the ball in a way that lets his team keep possession. To date, he’s never received a red card in his senior career (why does it feel unlucky to mention that?).

The duels he wins often come from smart body positioning or getting a well-timed foot in, not through big sliding tackles. It’s the “poke-and-pin” style you see from holding midfielders who rely on control rather than chaos.

My only real note is that when the ball is loose, he can occasionally just take whacks at it, which leads to further bouncing ball situations and additional variance.

Generally, his club usually doesn’t ask him to chase high (though we saw that above) or sprint indiscriminately, and that suits his style. He screens well, is always moving, keeps the structure intact, and steps out only when the ball enters his zone.

First and foremost, he cuts off passing lanes and delays attacks long enough for support to arrive.

➡️ Tackling & aggression

He’s a ball-winner, but not one of those Gallagher-style maniacs, and he’s usually hard to play through. His anticipation, discipline, and ability to win duels without overcommitting make him a strong shield in front of the back line. He’s not the fastest, and if isolated in space, he can be beaten. You just won’t see it all that much.

Perhaps his best defensive trait is the standing tackle. As soon as he can lean on an opponent, they probably aren’t getting free.

His value is in the cumulative effect: keeping the structure sound, recovering the ball early, and making it harder for the opponent to build anything dangerous.

➡️ Recovery sprints

His recovery pace is only so-so from a Premier League perspective, and that — plus the clarity we’d getting from more superlative progressive statistics — is probably the biggest question mark on the signing. It could ultimately impact how he’s used, and whether you want you to go fully man-to-man or leave an extra defender on the backline. If he loses a step, it could become an issue.

➡️ Coverage + blocking

When swinging out the wing to cover dribblers when the full-backs get pulled up, I expected to see more examples of him having trouble keeping up with quick movement, but haven’t really found much. I have some caution around him tracking underlaps, but again, his anticipation usually gives him a step — though it’s still worth considering.

He’s a great, additive help between the CBs, and looks comfortable moving as one. You can see a subtle movement below: his LCB gets stretched, he identifies it right away, fills the gap, becomes an LCB, and then keeps the runner offside.

He can get tough assignments through the middle. He racks up a lot of shot blocks, though he’s a bit lungy for my liking, and I’ve seen him turn his back a few times when he could have kept his body bigger (a pet peeve).

➡️ Aerials

He’s a great presence in the air, particularly in open-play situations. Here’s him hitting an early through-ball off his head:

He wins 61.9% of his aerial duels, which is fourth-highest among LaLiga midfielders with at least 50 such contests. His reading of the flight and timing of his jump compensate well for his average height; he can compete with most forwards in the air, and at the very least, he makes sure they don’t get an easy header.

👉 Set plays

He’s often assigned a zone or a secondary target, but isn’t the one skying over defenders to score goals; he’s part of the push. I’d expect that to continue.

On defensive set plays, he’s a solid contributor through the middle.

Defensively, yes, this profile fits a team that wants structure. Zubimendi can sit in front of the back four, pick his moments to step out, intercept passes, and hold the line. If you pair him with a more athletic partner like Rice in certain matches, the blend works well — Zubimendi as the cerebral half, Rice as the more aggressive ball-winner.

He offers the chance to hold those leads. You don’t often see him switch off or lose his man on basic actions. He can get caught now and then — a sharp one-two might leave him flat-footed. Most of the time, he avoids dangerous spots through smart positioning and timing.

In short, Zubimendi is a consistent, intelligent defender out of possession. He won’t lead the league in tackles, but he’ll be near the top in interceptions and duel win percentage. He uses positioning first, tackling second. He’s strong in the air and gives the back line a dependable shield. Arsenal’s ability to stay compact and cut out risk early should improve with him on the pitch.

👉 Injury record

Zubimendi has a pretty clean injury record. Over five seasons, he’s had a few minor muscular issues, but nothing chronic or structural. He’s never had surgery, never missed extended stretches with ligament or knee problems, and typically bounces back within a couple of weeks. His longest layoff came in May 2024 with a hamstring strain (34 days, 5 matches), but he returned without any lingering effects.

Availability has been a strength. He regularly plays 30+ league games a season — 33 appearances in La Liga in 2024/25 — and hasn’t been subbed very often. Though not un-physical, he’s not a reckless tackler or high-collision player, which probably helps, and at 26, he’s entering his physical prime. There’s nothing in his medical history that should raise red flags.

That said, there are no guarantees. The Premier League is more physical, the schedule more demanding, and the pace more relentless. But the signs are good: no major injuries, no recurring problems, and a track record of staying available.

🤔 Positional projection

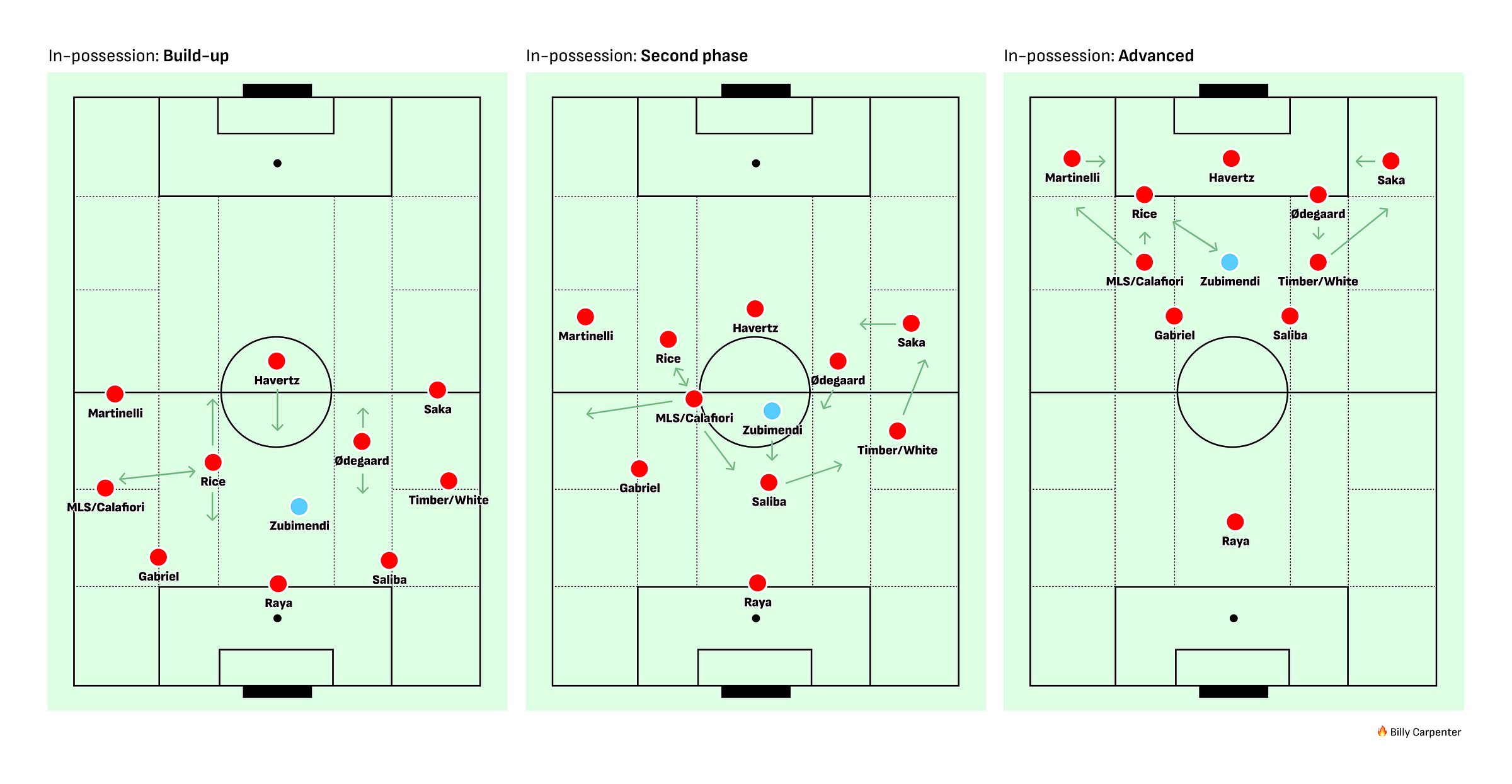

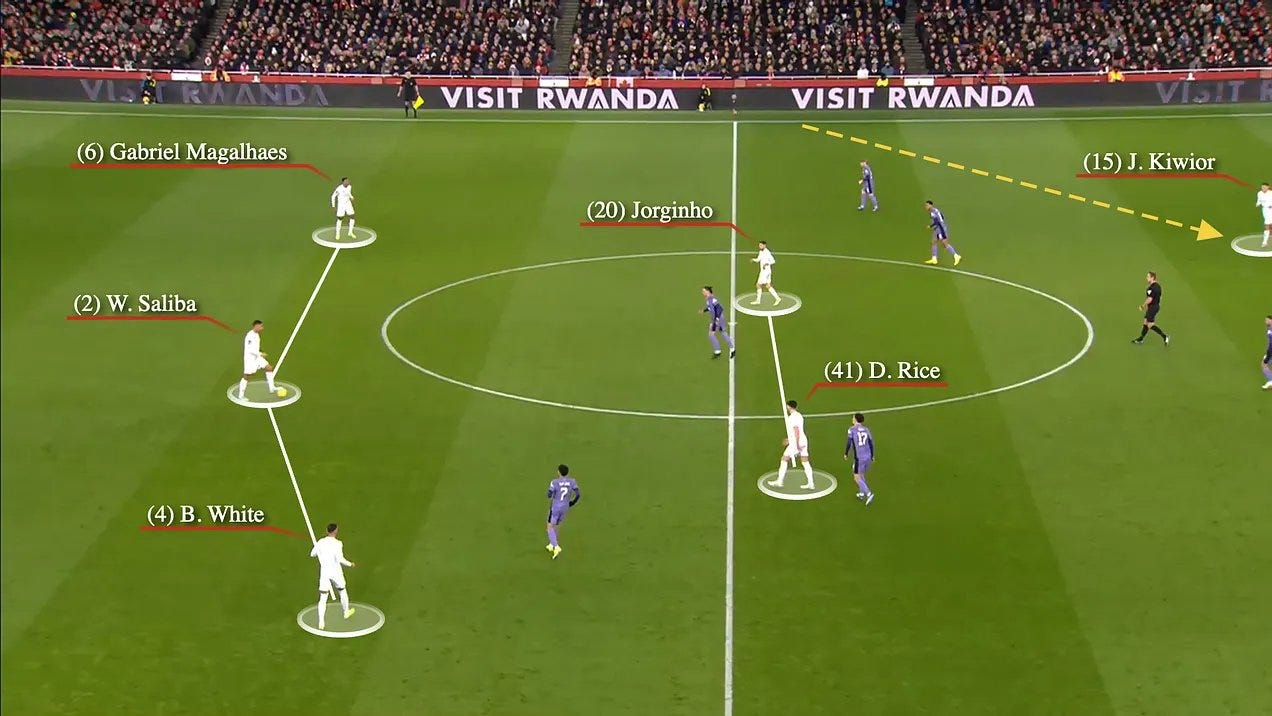

The simplest, and probably most likely, usage of Zubimendi is here.

In that example, Zubimendi essentially fulfills much of the Jorginho role, with more athleticism. He’d generally be the deepest midfielder, and the responsibility of the other pivot would be split based on the opponent’s look. Almost all of the build-up principles would stay the same. There are some nicely complementary pivot partnerships in Zubi/Rice, Zubi/MLS, and Zubi/Calafiori.

Out-of-possession, the team would spring and press out of this 4-4-2, with Zubimendi patrolling zones that he’s comfortable in for Spain and Real Sociedad.

Though Rice and Zubimendi can interchange there, it is nice to have Rice on the left to cover the zones potentially vacated by MLS. Then, on the right, Timber can help support the recovery speed of that right-sided “pod.”

Everything there looks balanced, clean, and perfectly sensible. Arsenal move on with a prime, experienced, steady hand at #6 who can offer tempo, duels, and incision.

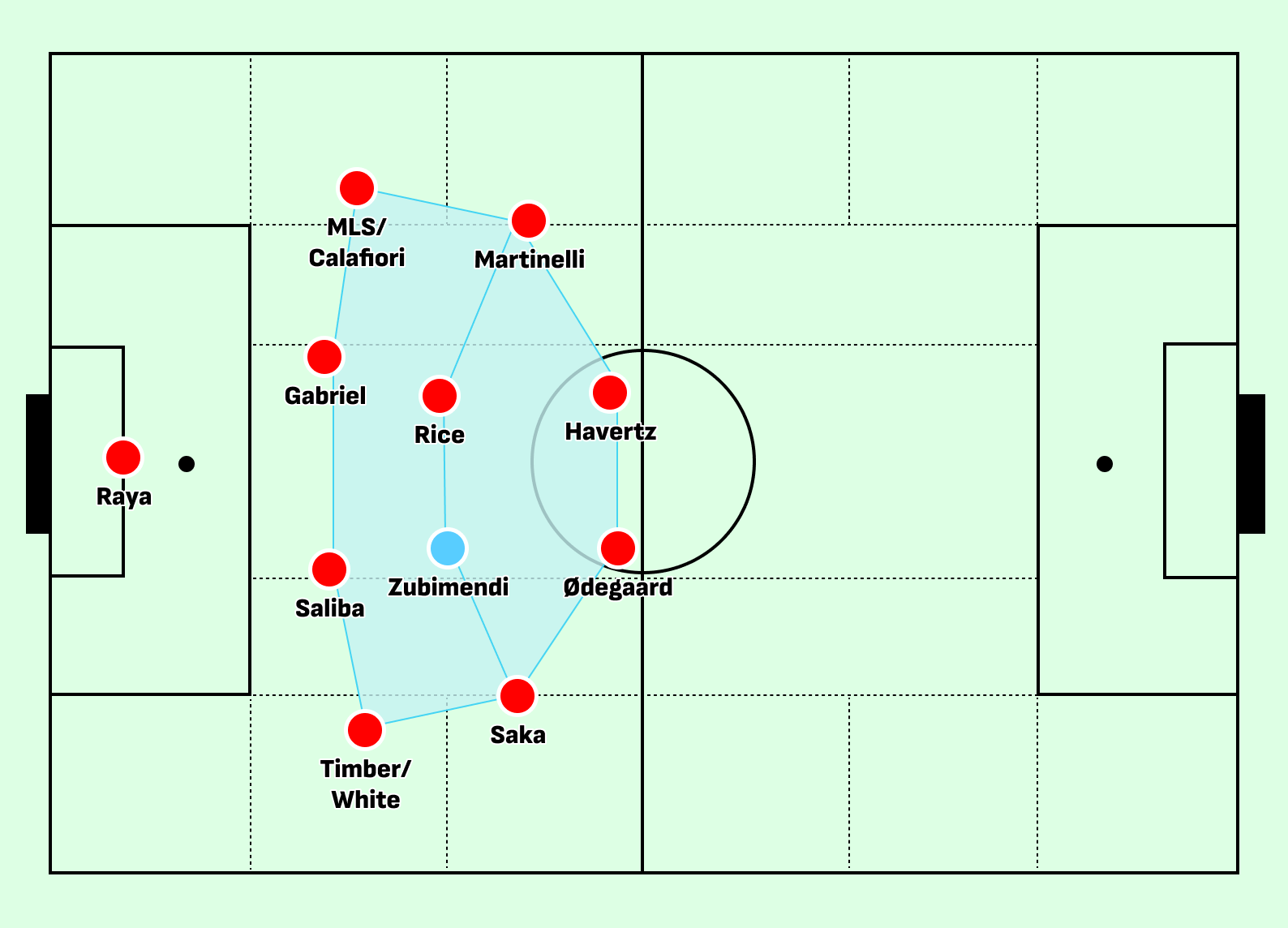

But regular readers of this newsletter will know that I’ve been obsessed with this “four-box-two” setup ever since it debuted last year.

I’ve loved it for its own reasons, but also for its potential: you see Saka and Martinelli more likely to get the ball in space. You see Havertz in a hybrid 10/striker role. You see the potential for a player like Lewis-Skelly or Calafiori to patrol a more typical left-back position, closer to their out-of-possession responsibilities. And if you swap Jorginho for a more athletic player, and White for Timber, and look at Rice patrolling that middle, the opponent has to ask: how the fuck do you score? What, exactly, is the vulnerability? It’s a hard question to answer.

With Jorginho dropping down, it looked like a fairly typical double-pivot deep, with Kiwior serving as an outlet and Ødegaard marauding on top.

As things progress, the left-back would float around the press, and often join the front-line. This is where having confident weirdos like Lewis-Skelly and Calafiori is a lot of fun, and I’d prefer those “pinning” responsibilities to be shared than for Rice to have to sit up there, ahead of the ball, by default.

In that Premier League victory, Jorginho’s passmap looked like this — which is fully within Zubimendi’s capabilities.

Unlike Partey, who is far more comfortable in certain zones of the pitch, Zubimendi is perfectly happy to receive the ball anywhere, including in tight little advanced pockets as play advances. Those snappy little dribbles can help unsettle the opponent, and his comfort with Ødegaard-style snap passes can help unlock things.

That initial shape would look something like this, allowing Zubimendi or Rice to push forward at will.

I like the idea of them switching and changing, as it’d offer Rice the opportunity to work a little more on the right: he can run and combine with Saka, freeing up his angles for three things: whipped, inswinging crosses; overlaps and cutbacks; and big cross-body shots like the one he scored against Newcastle. Zubimendi, then, has a lot of untapped potential to push forward on carries, setting up plays.

But Rice’s explosion has updated the calculus a bit, so I’m not too fervent.

In general, both options are on the table: Zubimendi as a deeper #6 and Zubimendi as a “double-#6” (or a “hybrid #8”) or whatever you’d like to call it. In the event of a Rice outage, Zubimendi also has the ability to hold the fort in a Zubi/Merino/Ødegaard midfield, as he’s already proven.

He’s comfortable all over the pitch, and I think it’s best to lean in more of a double-pivot direction, as it helps showcase some of Zubimendi and Rice’s unique traits: namely, game intelligence, the ability to arrive and push forward when the time is right, and the ability to do a little bit of everything.

Zubimendi’s work for Spain (which is kind of a 1.5-pivot, or whatever), swirling and rotating, might be the best template.

📉 Bear case

In the bear case, some of those questions stay lingering:

Zubimendi has plenty of functional athleticism, but he’s not elite in terms of raw speed or size. The Premier League is more transitional, more chaotic, and there’s a chance that it rears its head. I trust him inherently to manage tempo with the ball, but in the worst-case scenario, teams isolate him in space and play through him with quick one-twos or faster runners.

In this version of reality, the basic passing numbers don’t lie. He’s fine, solid, but not an elite progressor — and the eye test from legends and tacticos alike doesn’t change that. He ends up in the “slightly above average” category, and doesn’t demand the ball enough or spray it through.

You don’t need your #6 to be a pure chance-creator, but the best ones still give you flashes. If Zubimendi is too limited here, it doesn’t change things enough.

He’ll occasionally try the one-touch counter or whack it into traffic under pressure, and those moments can spiral into transitions.

This role takes time. Rodri and Partey both needed it, and Zubimendi also doesn’t offer a lot of TikTok highlights. If his intro period is more measured, I can hear the annoying social media grumblings of ‘what does he even do?’ already.

I’d personally err more to the side of “Rice at #6 against lower blocks, Rice at #8 against top sides,” but this feels like a commitment to Rice playing a little more advanced in all games. I worry about whether that cracks the “Fulham problem,” and think that has to be aggressively worked elsewhere.

His injury record’s clean, but the jump in intensity, volume, and travel could introduce issues. A hamstring flare-up or minor setback could disrupt his rhythm and hurt the team’s cohesion.

The bear case is simple: he ends up looking like a smart, capable, additive piece — but not a transformative one. Arsenal get a good player, but the midfield doesn’t improve quite enough to notice and tangibly take the next step. If that happens, it’ll feel like a lot of money for a marginal gain. Arsenal need more chaos, less control, and Zubimendi proves himself too much of a pragmatist.

📈 Bull case

If it all goes right, Zubimendi is the piece that elevates Arsenal’s midfield to the highest tier, and he formally cements his place as one of the world’s very best defensive midfielders.

What does that look like?

In this scenario, he joins early, steps in, improves our ability to play out, controls tempo, and lets us toggle between speeding up and slowing down as needed. The draws turn into wins, because the leads stay leads, and the 1-0’s turn into 2-0’s and 3-0’s.

The best version of this sees Zubimendi quarterbacking from deep, freeing Rice to roam and drive, giving Ødegaard a cleaner platform — all “want-to” actions instead of “have-to” actions — and it makes the midfield click in ways we haven’t quite seen. That Rice/Zubimendi axis could finally give us a full-spectrum midfield — defensively solid, press-resistant, fluid enough to control matches against anyone. Rice may go nuclear, as he already seems to be doing.

Nwaneri sitting on top of a defensively-sound, sweeping, orchestrating, all-action, mature double-pivot … sounds good.

The build-up tactics have looked perfectly sharp this year; the build-up performances have only been so-so, causing Raya to go longer than I’d like. With Zubimendi in the base, breaking a high press becomes a little more routine. His positioning and quick-release passing could eliminate one of our biggest headaches — those sticky matches where we can’t build through the middle.

In general, there’s a “game management” thing that he brings with him. Zubimendi can be the antidote to some of the pacing issues we’ve had throughout the last two campaigns. Leadership-wise, even if he’s not a shouter, his game speaks. At 26, he’s prime age, and ready to take responsibility. He could become a reference point for others — another player who embodies Arteta’s on-pitch ideals.

With more talent around him, his touches could increase and his final-third metrics could nudge upward. A few more assists, cleaner key pass numbers, maybe a couple goals from second phases in set plays. In a more domineering side, his numbers will reflect that. It’s not hard to see him with 90% pass accuracy, uber-efficient defensive metrics, and big touch counts.

The midfield feels somewhat settled: Rice, Ødegaard, Zubimendi, Lewis-Skelly, Nwaneri, Merino, Havertz, Dowman feels like a lovely future to build upon. Add a wingfielder type like Eze or Simons, and it has everything.

He is, hopefully, a ripple effect. His deep movements can potentially pull apart blocks and create space upfield. That opens channels for Saka, for Ødegaard, for the wingers. That’s central access.

I’m strange, but with Jorginho leaving and Partey hopefully out the door, this position was my #1 priority (with left-wing in second, and striker in third). As I’ve said elsewhere, I think it’s underestimated just how few people on earth can fulfill these responsibilities, particular the defensive ones, and none of them are more available, more prime age, cheaper, or come with fewer question marks than Zubimendi.

In this bull case, Zubimendi is a catalyst for trophies. Arsenal win the Premier League and/or the Champions League, and the midfield is a big reason why. Zubimendi adds stability and elevation, and his style of control and directness wins the day: some of the maturity of Jorginho, some of the duel capacity of Rice, some of the directness of Partey.

He is not just a cog, but a force multiplier. His presence could raise Arsenal’s floor (bad games are less bad because he ensures some control) and raise their ceiling (good games become dominating ones). He’s the kind of player that can make those around him appear better by structuring a game on our terms; there’s a little bit more snappiness to action, there are fewer mistakes, and the attack jumps a level.

Should some version of the bull case happen, Arsenal can finally take that final step. And Zubimendi helps us crack that safe, once and for all.

Know what else is competence porn? This blog right here.

Are we Berta's BBQ now