Scouting Mikel Merino

A big scouting report for a big midfielder. Taking a nuanced look through the Arsenal target’s experience, tape, analytics, passing, duel prowess, position, areas of concern, value, and a lot more

“You must keep sending work out; you must never let a manuscript do nothing but eat its head off in a drawer. You send that work out again and again, while you're working on another one. If you have talent, you will receive some measure of success — but only if you persist.”

― Isaac Asimov

It’s always about timing with Mikel Merino.

After his 119th-minute goal in the Euro 2024 quarter-finals against Germany, he needed a moment to process.

“Honestly, I took two or three seconds to realise what had just happened,” Merino recalled to the Athletic. “I headed the ball and the stadium went quiet. Then I opened my eyes, and instantly saw the ball in the back of the net.”

The run-up to the goal illustrates the kind of player he strives to be.

After squeezing the Germany side after a throw-in, Spain won the ball. Merino set off on a striker-type run up the middle while logging the placement of his teammates.

Once play settled and he reached his happy place as a high-LCM at the top of the box, he pointed out the free man to Carvajal. The ball headed to Cucurella.

Once Cucurella got it, Merino advised a pass out to Olmo.

Then, Merino attacked the blindspot behind Rüdiger. Olmo delivered a great cross — what a player he can be — and Merino jumped and twisted to generate torque. The ball went into the corner of the net for the win.

Merino celebrated the winner with a trip over to the corner flag, where he did the same celebration, in the same stadium, that his father did 33 years ago.

“The point was to make me look bad,” joked Miguel Merino. “If he had already surpassed me, now I don’t have the exclusivity of the Stuttgart goal, either. Now I just have to be quiet and give him a big kiss, because he deserves it.”

As with his orchestrated header, timing was a critical factor in Merino’s earlier successes — and travails.

➡️ The early years

After starting his career at CD Amigó, he was scooped up by Osasuna, the club where his father had played and, ultimately, managed in various capacities with the youth and reserve sides.

Merino’s performances as a teenager for Osasuna in Spain's Segunda División garnered him some buzz. He became an every-week starter as an 18-year-old, then proved himself something more dynamic and interesting in the follow-up campaign (or so I can infer by the grainy clips I can dig up).

Borussia Dortmund, led by Thomas Tuchel at the time, signed him for €3.75m. Interestingly, he joined alongside fellow teenager Alexander Isak, who has similarly taken a winding road through Dortmund, Real Sociedad, and Newcastle.

Merino played a single year in the Bundesliga. It’s fair to say the move was ill-timed, as there was a glut in the midfield. Minutes were tough to come by, and his only two starts were actually at LCB, once in a back-two and once in a back-three.

That’s right: Arteta is looking to sign another CB.

When he did complete this role, he was a certifiable touch monster. Here’s him going 112/124 (90%) as a 20-year-old passing from LCB against Augsburg.

During the process, Tuchel hammered home the value of details.

“He insisted on the importance of having the ball, keeping it, playing the simple pass, to the right place with the first touch in the right direction and with the correct foot,” said Merino to Barrons. “When you’re young you don’t realise but these details make a difference.”

While he showed flashes of the game-feel and physicality that would become his hallmarks, he also had some low losses and growing pains. The club won their fourth DFB-Pokal (Sokratis! Auba!), but Merino got all of 20 minutes in that competition and only tallied 8 appearances and 298 minutes in the league.

“Dortmund wasn’t like I hoped it would be,” said Merino to the Athletic. “When you go on an adventure like that, you get into a good mindset to play, to develop, to become an important figure. Then I arrived and things were not as I expected. I learned a lot from a top club with top players and I’m the person I am because of my experience there. That helped push me to a higher level.”

After the season, a surprising club came calling.

➡️ To Newcastle

Rafael Benítez explained how it came to be.

“It was a special situation because it wasn’t easy to get players from Dortmund to Newcastle then,” Benitez, who managed Newcastle at the time, said to the Athletic. “But we told him our ideas, we convinced him to come, and made sure he was comfortable.”

There may have been some BVB undertones to Merino’s quotes in his announcement.

“I'm looking forward to touching the ball, meeting my new team-mates and starting to play football,” said Merino.

Emphasis on “touching the ball.”

Joining on a loan deal, his introduction to the Magpies was impressive enough that the move became permanent by October. If there’s any proof this move was a “flop,” I can’t really find it — the stats and performances I’ve reviewed all look like those of a plenty-talented-if-still-developing player, though he battled a couple of knocks and was less consistent in the back half. Nevertheless, his YouTube clips are reliably filled with a half-dozen Geordies in the comments section asking him to come back.

In almost every interview with Merino that I could find, he talked about how formative his time in England was.

“When people ask about the Premier League, I tell them: when I was going to play, I was preparing myself mentally to go to war,” Merino told the Guardian. “I was going out thinking about the fight.”

He expanded:

“In Spain, heading on to the pitch you’re thinking about tactics, positions, the ball. In England, I didn’t think much about the ball; it was more about the battle. I am who I am because of the Premier League: it made me harder, stronger, taught me to take the hits. You have a perception of football and you get there and it’s not that: it’s more physical, more direct, the game doesn’t stop, these are men with enormous bodies. I understand why some can’t adapt.”

The importance of timing was a lesson that the league doesn’t deliver lightly.

“The league changes you,” Merino continued. “I remember Rafa [Benítez] telling me to play quickly, one or two touches. He said if they get to you, they’ll hit you or take the ball.”

Alas, his time at St James' was short-lived. His contract included a €12m release clause if a Basque club inquired for his services — Benítez says he “wouldn’t have come without it” — and Real Sociedad happily paid up that summer. Merino returned to northern Spain.

By December of that 2018-2019 season, timing was on his side: Imanol Alguacil had returned to the top job at his beloved club, employing his appealing brand of front-foot, attacking, high-pressing football. Merino has scarcely left the starting eleven since, making 241 appearances across competitions.

During this period, he's won the Euros, the Nations League, and the Copa del Rey — adding to a trophy haul that includes the DFB-Pokal and U21/U19 European titles.

As loyal as Merino has been, wistful thoughts of the Premier League tend to trickle back into his interviews.

“It's like a movie,” said Merino to CBS. “So it taught me a lot. Right now I am using it here in La Liga. I try to be physical and win a lot of balls. So I'm sure if someday I have the opportunity to go back, I'll be ready for it because I already know what that league is all about."

Perhaps it’s time.

📖 Player overview

We’ll start with the physical stuff.

Merino is listed at 6-2 and 183lb, which is the same height and a bit lighter than the current signing du jour, Riccardo Calafiori.

In other words, he’s a big midfielder who feels big when you watch him. His frame calls to mind modern contemporaries like Leon Goretzka, Joelinton, Adrien Rabiot, and … Granit Xhaka.

The Xhaka comparisons will proliferate, and — spoiler alert — I’d imagine that Merino would be deployed in much the same way that Areta used Xhaka in 2022/2023. But they differ in significant ways. Xhaka is one of the best deep spray-passers in Europe, and Merino has more athletic gifts, and is more anxious to prove it through direct engagement.

See:

Xhaka (22/23): 3.67 defensive duels, 2.67 aerial duels per 90

Merino (23/24): 6.73 defensive duels, 11.23 aerial duels per 90

I pulled a 10-game sample from earlier in the year and Merino contested 350 duels in them, good for 35 a match — or more than Rice and Palhinha average combined.

Xhaka and Merino are similar in their guile, work-rate, and how they both can look a little sturdy and rigid when turning deep.

As you’ve surmised, one of the primary ways that Merino makes an impact is through the air. He’s a big dog. As I tweeted last week:

Merino was the #1 midfielder for aerial wins in Europe's Top-5

He had 50+ more wins than Souček, Havertz, etc

He had more aerial wins than Van Dijk, Pinnock, etc

Per 90, he had more than Gabriel, Saliba, White ... combined

He leans, bullies, and jumps high — in all aerial situations. Players bounce off of him.

Though I’ve watched him plenty, you notice new things whenever you study a player. I found myself appreciating his immediate burst more than I had previously, which is a product of his level of anticipation and engagement — he comes alive quickly in the duel and has the strength and leverage to shove off big players, as I saw him doing against Tchouaméni. His work-rate is ever-present. He just keeps running late in games. By my once-over, he led Real Sociedad in distance covered per 90 in the Champions League.

As I’ve said before, top speed is a silly stat — hostage to game factors, play styles, roles, etc — but I was unable to find anything remotely impressive for Merino. He never feels slow, always sneaking steps and anticipating, and I don’t really have any examples of him being outrun conclusively. But I kept scrolling to see where his top-speed (29.1 km/h) ranked among Champions League players and I eventually gave up after a while.

There are multiple factors to consider there. For one, raw sprinting pace is more common, and more important, on the flanks. For another, I’d surmise that he’s roughly on the level of a Guimarães in terms of effective game pace, and he fares just fine. Still, a big part of his appeal is how he eats up ground, bullying and disrupting in La Liga, which would be awfully helpful in the event of a Rice outage. As such, you’d love to have zero reservations for the Premier League pace re-transition, as La Liga has fewer high-speed runs than other top leagues. It’s not a blinding concern — I’ve watched him against Camavinga, De Jong, Valverde, Griezmann, the like, and he often looks like the athletic one — it’s just something to bookmark.

➡️ Adjustment period

In terms of transition, there are few better clubs for Arsenal to receive a player from than La Real. They play a thoroughly modern, aggressive, fun style of football — and they do it regardless of opponent.

In that chart, you’ll see “PPDA,” which is shorthand for “passes per defensive action.” That’s a (really) rough approximation of how intense a team’s press is in higher areas. This means Real Sociedad’s press is (nominally) of a higher intensity than that of Arsenal, which tracks with the eye test. They go all-out.

They play a little bit like Plucky Arsenal, with the volume and risk tolerance turned up. They generally start with a lone-ish-6 (Zubimendi) and standard full-backs, but they alternate between deep circulation (where Merino helps, but most of the play sticks back with the keeper and the backline) and “Route One” balls straight up to him. Many of their possessions start high up because of how effective they are at disrupting build-up play; they go fast from there. This year, especially so.

Merino has had a stable environment to ply his craft. I thumbed through games throughout the years, and though there have been some alterations to the system (a 4-3-3 that morphs into a 4-2-3-1 or a 4-4-2 diamond) and tweaks throughout, the role for him is usually the same: a box-to-box left-8.

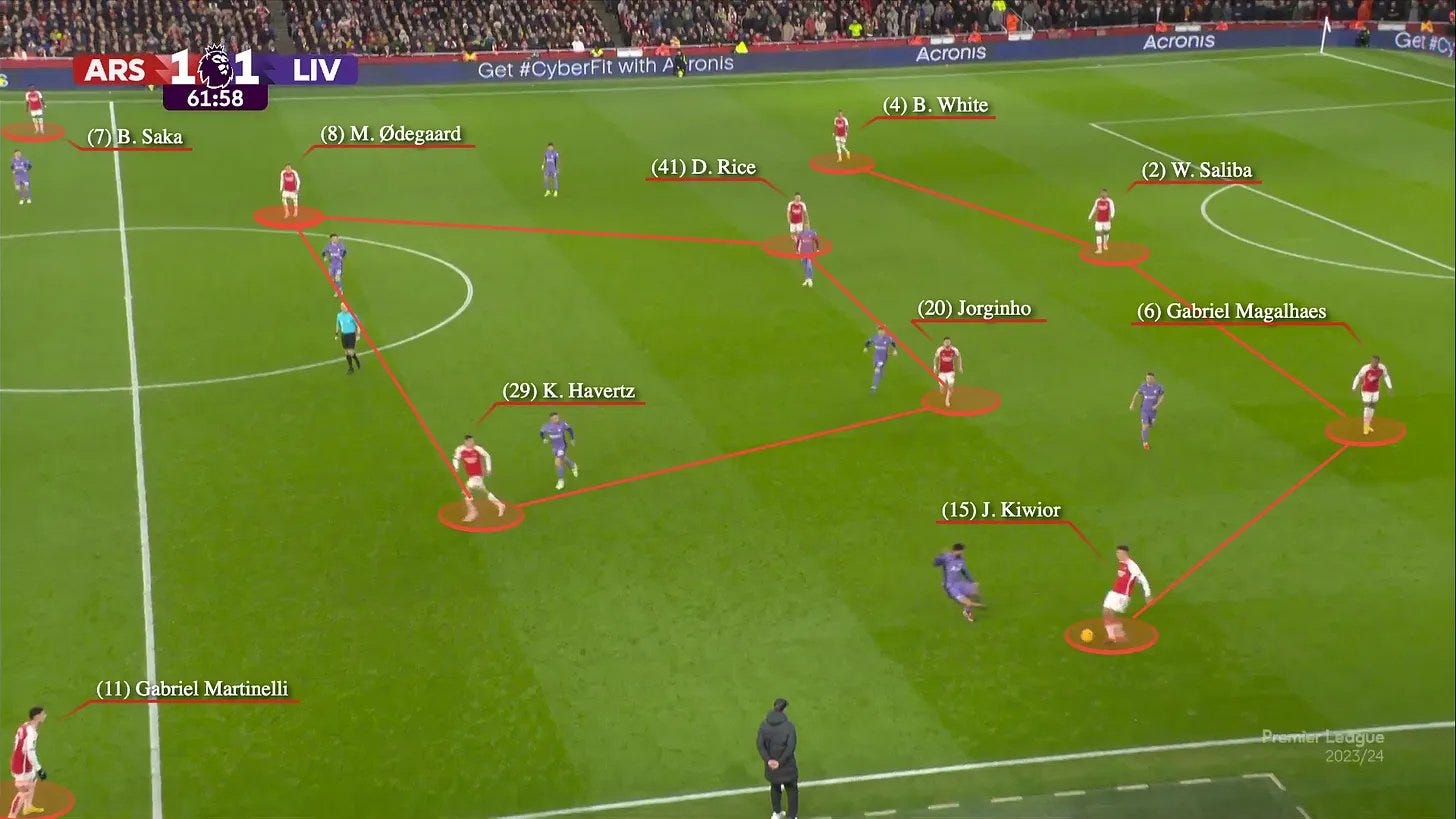

In the press, La Real can commit a little more forward than Arsenal. But Merino’s role is similar to Xhaka in 22-23, or Havertz in the early part of 23-24, or Rice when he played higher up the pitch.

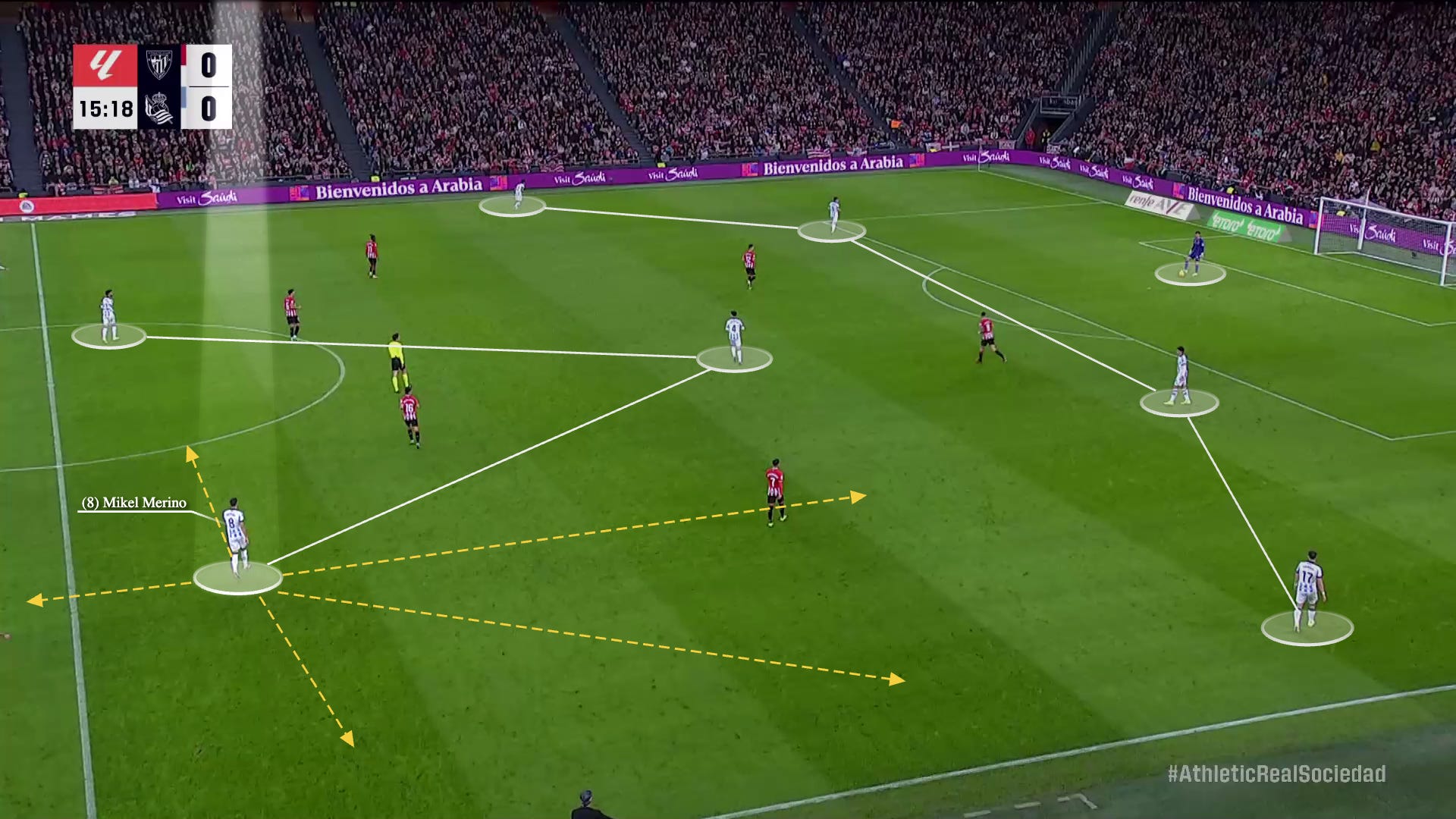

In the block, he helms the left-8 in a 4-4-2 — which, again, is exactly what he’d do in the left-8 at Arsenal. Real Sociedad’s version is more man-orientated, jumpy, and aggressive. It was hard to find a moment to screenshot where they were lined up and nobody was sprinting. This was the best I could do.

In build-up, it often looks like this. Merino has optionality.

Depending on the opposing press, Merino drops down to help Zubimendi, who often splits the CBs — which makes Merino a bit of a holding midfielder. In this system, Zubimendi is not a standard-issue #6 in some ways, because he doesn’t want every ball in build-up — he’s content to hang behind a marker and create space for others; this means that Merino (and, less often, Brais Méndez) help.

But if there’s a mismatch, or a particularly tough opponent, they’ll send it right up to Merino in large quantities. 58.3% of Real Sociedad goal-kicks were launched last year — they’re not Brighton — which helps understand some of the possession statistics, and helps illustrate how Merino is able to rack up so many aerial duels.

To give you a sense of a Merino performance, here’s a look at one of his passmaps. This one was against Real Madrid in a particularly active game — he had 66 passes and 108 total actions on the day.

…and to give you a sense of the level of praise he gets by those who watch him most, you can turn to his coach.

“He's the best player in the league," said Alguacil in 2021, after La Real climbed to third in the table, right behind Real Madrid.

He waited a beat to make sure it sunk in.

“I said it before and I'll say it again in case it's not clear," he said. “Mikel Merino is the best player in La Liga."

Let’s interrogate that, Imanol.

📊 Statistical overview

Here, you’ll see three years’ worth of data.

Some notes:

The first two seasons were consistent, as was much of his career.

His aerials and recoveries are sky-high. He generally hits a good amount of through-balls and progressive passes. His other passes (namely his short stuff) require more inspection.

His carrying, dribbling, and losses don’t look impressive here.

His progression and through-ball numbers look nice. Last year, his advanced passing numbers dipped. As La Real went through some tactical permutations, he’d increasingly turn and hit it forward immediately. We’ll dive into how effective that was, but the numbers don’t look great.

Next, let’s compare him to the current Arsenal cadre.

More notes:

The defensive numbers are superlative.

You’ll also see that he attempts more forward passes than Rice — on 12 fewer passes per 90.

In a vacuum, I would prefer to see more crosses, more touches in the box, more dribbles, and more shots out of this role.

His progressive passing is a nice surprise (6.24 per 90).

One of the next things I wanted to check out was how the placement of his touches compares. I pulled a few campaigns that I thought would be most telling, including those of Xhaka and Partey in 22/23.

Surprise, surprise. There’s a real similarity in the placement of touches for 22-23 Xhaka and last year’s Merino.

🧾 Showing my work

La Real are always of interest to me. I love the direction of the project and their style of play, so I’ve watched them more than most other clubs in Europe. I’m familiar with Merino.

For this piece, I watched (or rewatched) a smattering of full-90s: including PSG (both legs), Inter (a), Barcelona (a), Real Madrid (a), Benfica (h), appearances for Spain (Colombia, Albania, Germany), three matches in 19/20 with Ødegaard (Barcelona, Athletic Club, and Osasuna), and scattered clips from his time at Dortmund, Newcastle, and Osasuna. I then created a long playlist (~250 actions) of his duels, passes under pressure, progression, and deep losses.

If you think that’s a lot of games to watch, you’d be surprised how quickly you can get through some La Liga contests if you fast-forward through the stoppages 🤪.

There are still blindspots and assumptions.

➡️ Previous ranks

In January 2023, I ran D.U.E.L.S. (which stood for “Depth Upgrades for the Elusive Lone 6”), which raised Declan Rice as the clear #1 defensive midfielder option worldwide at the time. Merino ranked #27.

In the post-Rice future, we adjusted our parameters, and in November, I created P.W.R., or “Pair With Rice” score, to find a player that could replace one of the older 6’s in the squad (likely Thomas Partey) while also playing alongside Rice. Merino missed the 22-player cut.

Why didn’t Merino fare better? Bascially, my rankings are after players like Nico Williams and Declan Rice, and are pretty unkind if you are a) older than ~27 and b) presumed to be expensive by Transfermarkt. (This didn’t apply to my FB search, as I turned the age thing down and the value thing off).

Merino turned 28 in June, is listed at €50m by Transfermarkt, and didn’t have the raw passing or carrying profile to overcome those weights statistically (and I didn’t add eye-test metrics for all the players that miss the original list). Transfermarkt data is no gospel, it’s just the “worst option except for all the others,” as the apocryphal Churchill quote about democracy goes. Manuel Locatelli, for example, is two years younger, boasts better passing numbers, and was listed at half the price of Merino.

The reason why I point these rankings in the direction of younger profiles is probably obvious. For one, it is somehow increasingly turning into a physical, end-to-end league, and I’m paranoid about making Casemiro-type signings. For another, you want to be judicious about handing out healthy contracts to the 27+ crowd, as you’re unlikely to recoup your investment (unless Saudi comes a-calling).

At a certain stage, though, it becomes a necessary part of the project — and I’m probably overdoing it in my calculations — but you still want to be the one offloading the Raheem Sterling-type contracts, not starting them. Exceptions apply; Jorginho deals and Casemiro deals are not the same in terms of risk.

If followed rigidly, there is a problem with such a system — he says to himself — and that is this: everybody seems to be after such players, and the value seems to be getting sapped up by the day. In an age when a nicely talented striker like Rasmus Højlund is purchased a year early so his price is “only” €73.90m, or, I don’t know, Elliot Anderson goes for €41.20m after logging 1,441 Premier League minutes, it’s worth asking whether today’s market efficiencies lie elsewhere.

Brighton does well, yes. But I look at the example of a club like VfB Stuttgart, who, in one window, pieced together various age profiles and misfit toys, and finished atop Bayern in the table. What would a healthy-budgeted version of this look like?

The point is that it’s not “either/or,” but “all of the above.” Value exists everywhere.

As James Benge reported:

Sources close to Arsenal expect a summer where the profile of new recruits is more akin to Jorginho and Trossard, two more experienced additions who arrived at a later stage of their career then sporting director Edu typically looks to recruit.

Jorginho and Trossard, for example, jumped up the ranks as soon as I turned the age modifier off. I’m not able to re-check the PWR rankings with Merino (it’d require doing new manual evaluations of 30ish midfielders, and that’d take too much time, so fuck off, he says warmly), but I generally imagine it’d be a similar case (though not as far).

A static shortlist has its limitations. This is why I’ll eventually work toward a dashboard where you can adjust some dials (readiness, value, age, risk, eye test, etc) and the lists can re-sort in real-time. Alas.

➡️ My priors

I like discussing priors instead of ignoring them. Upon hearing the links, here’s what I thought of Merino.

He’s clearly a good-to-great player who passes the “non-negotiables” test with aplomb.

Depending on the fee, he now has a good-to-ridiculous quality-to-value ratio. He is simply better at the football than almost any midfielder going in this price range.

But: I consider a spot next to Rice to be a rare offering, and was ultimately after a more overpowered passer or dribbler (and/or ball-striker) in this role. I’m concerned about lineups without Jorginho and Zinchenko in them, and I’d like to add somebody who can stand on the ball and dictate play if needed, and if not, to unsettle blocks with nasty passes and/or provocative dribbles. Could Merino be that player? I don’t know; I sought big swings. They may be unavailable.

Also: some of his stats, particularly those around passing and carrying efficiency, are worth a pause.

My concern, then, goes back to our introductory concept of timing: who is going to take care of the tempo?

In summary, I had very little doubt about Merino’s quality or cultural match for Arsenal; I was unclear about the profile fit. The risk is that signing Merino would represent a strengthening of some already-durable strengths, while leaving some niggling weaknesses unaddressed.

We are reminded of Amy Lawrence’s quote:

Sometimes, when identifying a signing, the role they will play is crystal clear. But increasingly, those who catch Arteta and sporting director Edu’s eye are more about general footballing qualities and human characteristics than a specific positional profile.

Let’s dig in some more.

🧠 Playing temperament

I again use the words “playing temperament” because it can feel presumptuous to talk about a player’s psychology or mental state from our vantage point.

Warning: there’s not a lot of nuance to this section. Merino has a pristine reputation, not least of which with me. You’ve heard his current manager calling him the best player in the league. There are likely endorsements in the form of Martin Ødegaard, who played alongside him, and Kieran Tierney, who said this:

"You have world-class players like Martín Zubimendi, Mikel Merino, Brais Méndez. It’s not that people don’t think they’re good, it’s just that if you’re only watching the Premier League every week, it’s hard to know. They’re world class."

Luis de la Fuente referred to him as an extra coach of the Spanish squad.

"For me, Carvajal, Rodri, Mikel Merino, Oyarzabal... are players who you tell things to and you see that they quickly understand what you are asking of them.”

I’ve also observed that, anecdotally, the more obsessive about La Liga you are, the more you seem to revere Merino. On Twitter, LaLigaMichael has said that Merino’s performances have been better than Frenkie de Jong in the league. A bold claim, to be sure, and retweets aren’t endorsements. He’s also put him in his teams of the season five times in a row, only matched by Toni Kroos.

Back to the temperament stuff. He goes hard, is highly communicative and demonstrative, is consistent week-to-week, and I’ve never seen him look disengaged or lazy on the pitch. I’ve seen him with the armband a few times (and don’t know how to confirm how many times he’s done that).

In build-up, he is a bit of a minimalist. He has a good eye for simple associative play and movement, is regularly moving, thinking, and pointing out options, but is not overly-ambitious with his range. He’s also happy to draw a foul deep.

In the middle and advanced thirds, he can be greedy. He is generally working to feed direct, first-touch balls toward the goal as quickly as possible. He wants goals to happen. If not, a little bit of mayhem in the box is a suitable compromise.

But as I went deeper through his career, I saw a few different Merinos — the safe orchestrator, the line-breaker, the impatient assister. I saw him flexing a bit more range in the earlier days as well. It seems to point to an ability to adapt based on the needs of the squad.

When defending, his off switch is broken. In his current iteration, that means constantly enveloping the opponent and trying to dispossess it with his core strength and long legs.

He can definitely wade into the over-aggressive territory as the leader of the Real Sociedad press. He will usually choose the more combative option, fouling and being fouled in equal measure. He runs after everything, a Patron Saint of Lost Causes.

There’s also this anecdote in an interview with Luis Miguel Echegaray:

Merino is an articulate speaker. We could have done this interview in Spanish but he chose English as he wants to keep improving, but it's very, very good. He says he learned it while watching Suits (Harvey is his favorite character) and playing in Newcastle.

He’s been pretty YOLO in the final third, and preposterously aggressive in the duel; how you feel about that is up to you, but I can’t find anything else to critique for this section.

👉 In-Possession

➡️ Passing and receiving: Small, tempo, build-up, progression

Merino is a sometimes-straightforward but smart and additive presence in build-up. While he had his highest-touch games earlier in his career, he is now more conditional about when he drops deep to receive, as much of that responsibility falls to the back four, goalkeeper, and Zubimendi.

🎶 It’s not unusual 🎶 to see him drop down into a double-pivot like this, and I made sure to catch some games where he was highest-touch from deep.

Zubimendi, as we’ve covered, isn’t just a possession-hogging #6. He is a servant, roaming around and looking to do the right thing. In many cases, that means dropping between the CBs to receive — but in many others, it means dragging a defender away and letting a player like Merino get the space.

Merino is really good at preserving angles, creating space, and receiving with his momentum going in the right direction. He is not ambipedal — he is definitely left-footed, and prefers to use that foot whenever possible. He’s not clumsy with his right, however.

This gives you a good sense of what he’s like in the early phases.

He learned his lessons in the Premier League. He’s highly focused on cutting out unnecessary touches, scanning, pointing, anticipating his next action, demonstrating empathy — and an obviousness — to his teammates, dropping into the right pockets, and generating third-man runs. It’s fairly basic-looking but mostly effective. For all his “fuck it, we ball” exploits up the pitch, he has calma back there.

When facing a lower block, or when rotations have occurred, he can transpose his early experience at LCB by falling back there as needed. This gets interesting when you consider rotations with Rice and Calafiori. This is also when his passing range looks best, to my eyes.

He also has a switch in his locker from these zones.

As the ball moves up the thirds, he excels in link-up play. Here’s a clip that’ll make you happy: Merino combining with Ødegaard to rip up a block. Merino one-touching, the pair moving defenders every which way, pushing things forward, ending in an Ødegaard assist. We haven’t seen much combination play from our 8’s.

There are some shortcomings.

For one, his desire to limit his touches can sometimes lead him astray as the ball moves up the pitch. New information can be presented, but he looks to one-touch it anyway.

For another, he can be inconsistent on the turn. He sometimes looks blocky, and his first touch is solid but not perfectly reliable; it can be bouncy at times. This is a particularly stinky one (keeping things in proportion when you’re offered up clips is difficult) but I thought I should show you an extreme example.

If he has one player to beat, he’ll usually figure it out, and draws a lot of savvy fouls, like Jorginho would. But if his teammates put him in a tough position, and he’s enveloped, he’s not naturally low or wiggly enough to get himself free.

If there’s a chance for an immediate regain, he is the first person to push forward. He often winds up with the ball a second or two after a loss.

To me, this limits his potential as the predominant low receiver — where he does have brains and calma, but also these limitations — but it projects well as an #8 and a second pivot.

I don’t doubt that he’s the kind of player who has a few different chapters left in his career, as I’ve noticed him modulate his play season-to-season based on the needs of the team. But I’m easily most comfortable with him at the eight.

➡️ Passing: Big passes, final balls, efficiency

Here is where things get most exciting and mixed. I’ve argued that Arsenal should have a higher risk tolerance as the ball moves forward, and should trade a few more high losses for more goals. This is especially true in a future with Calafiori and Merino adding to the most fearsome counter-press imaginable. Regain the bounces, exploit the chaos, go.

Merino offers that possibility.

Something like this is the most simplistic way to show his value: scan, touch, deliver forward ball.

That’s where you feel optimistic for Martinelli.

Here’s another nice one, which shows an open turn toward the defender, followed by a little carry and a looping through-ball, perfectly weighted. Let it not be said that he’s some untechnical brute.

These forward touches — particularly after a regain — looked especially deadly when he had a runner like Isak ahead. Forward, forward, forward.

He’s comfortable in that high-left pocket, and has spent a lot of time there over the years. Here, he accepts the type of ball he’d get at Arsenal.

Then, he turns and pushes it through to the runner in behind. It could be Martinelli, Jesus, Havertz, Trossard, or even Calafiori here.

His passing superpower in the final third is these quick, anticipatory combinations — which are also strengths of his potential left-sided partners (Martinelli and Calafiori). When they come off, they look great.

And I’d be foolish not to show you another ball in the box to Ødegaard. Assist, Merino.

He’s a solid crosser. Not in the elite tier of whip, but plenty capable.

…so what’s the catch?

Whereas I’d push for Arsenal to have a slightly higher tolerance for losses up top, Merino errs too far in the other direction. The cumulative ‘cost’ for a chance — that is, the number of high losses — was too high this past season. He worked too hard and tried too much for 2.8 expected assists.

I’ll give you two identical opportunities. The first one is a good one — Merino is on the same wavelength as the runner and delivers a nice ball into the box.

In this next one, the runner is similarly between the two CBs, but doesn’t have a step, and isn’t making a run. Merino seems to see and acknowledges this — but says “fuck it” and rifles it in there anyway.

This is commonplace for him, and I don’t doubt that it aligns with the managerial instructions. Whereas the deeper players at La Real can be overly-retentive, and Méndez on the other side can be slick and technical, the mandate on this side seems to be Heavy Metal, Klopp-style chances: create some mayhem and see what happens. Trying to snap together a chance right after a duel also leads to advanced miscontrols and dispossessions.

Here’s another, simple example. He forgoes a control touch to hit it first time. It’s a little inexact and rolls to the keeper.

It’s nothing big as an individual moment — I actually like the intent — but there is just a raw accumulation of these urgent, slightly-off balls that help keep his pass completion at 76%. We’ll get back to that.

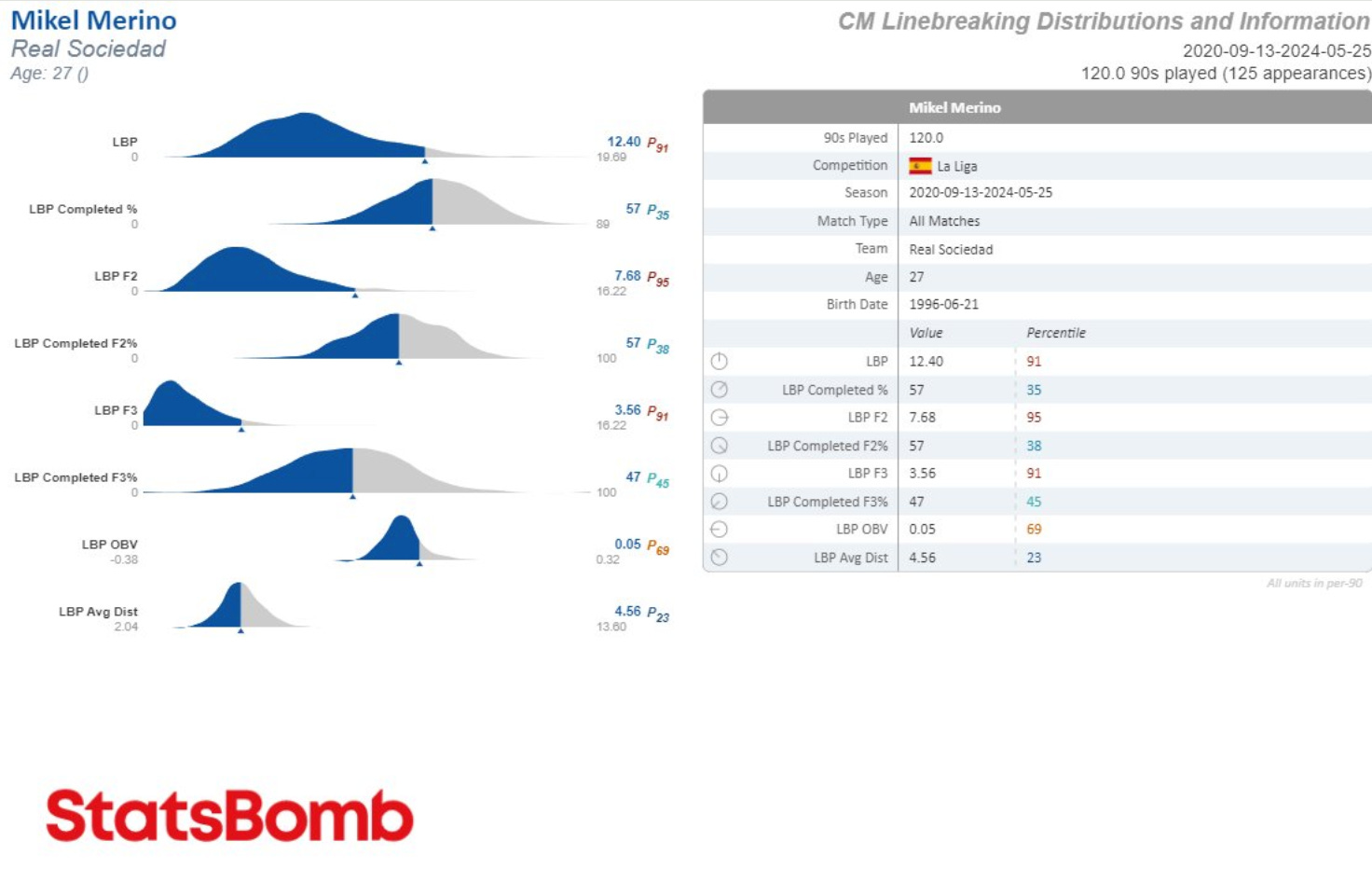

I feel this chart from StatsBomb (and sent to me by GiantGooner … thank you!) does a good job of illustrating the transaction. Here’s a four-year sample, which includes 125 appearances in all.

Here’s a summary.

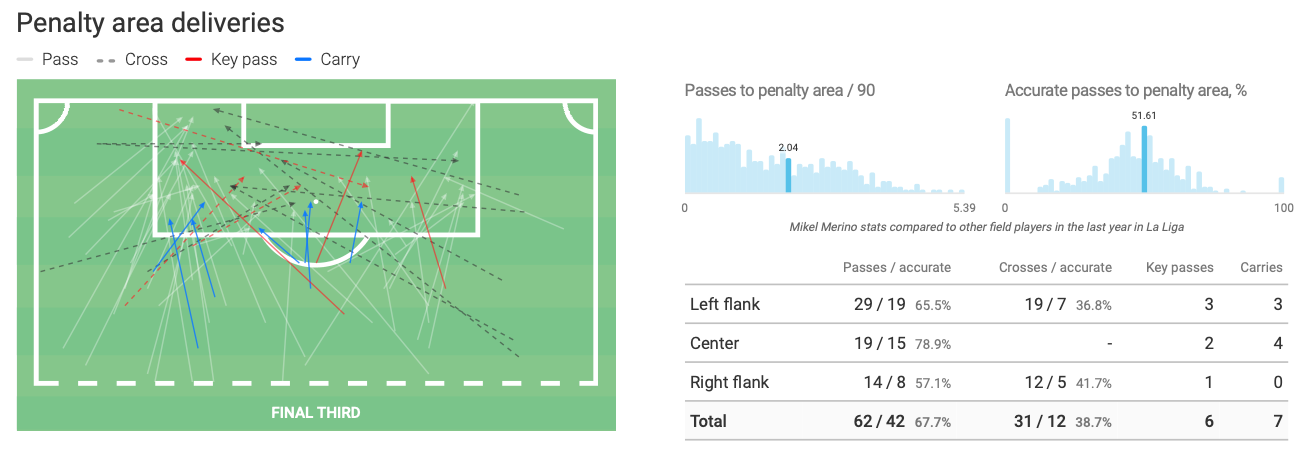

Merino offers a very high quantity of line-breaking passes attempted. He is 91st percentile in line-breaking passes overall; he’s 95th percentile in the opponent half (“F2”); he’s 91st in the final third (“F3”).

His completion rates on these passes are low. He’s 35th, 38th, and 45th percentile respectively.

His “on-ball value” from these passes is solid in this sample (69th percentile, nice), but awfully low in this last season (13th percentile, not so nice). I have a somewhat complicated relationship with that stat (which tries to measure each action on the pitch in terms of scoring and being scored upon), but it’s worth noting.

Overall, I’ve seen a lot of concern that Merino’s pass completion is generally around 76%. The first thing to remember is that pass completion matters very little on its own. Kevin de Bruyne is arguably the best passer alive, and he hasn’t broken 77% in five years. It’s all about what you get for your passes, what situations you find yourself in, and your role on the pitch.

Merino’s role is often to a) bring the ball down on an aerial and progress it quickly or b) steal the ball and progress it quickly. If you think about those situations, they are urgent, messy, and opportunistic by their nature. His actions transmit an aggressiveness throughout the pitch.

He’s not whipping around like KDB or Bruno Fernandes, though, and these passes can be teammate-dependent, as he’s not generally laying it out on a plate — he’s giving it to them in a forward area, and there’s more to do. In the past year, it can be easily (and correctly) argued that the risk tolerance was upped too high, and the numbers piled up better with teammates like Isak and Alexander Sørloth (who left to Villarreal last summer).

Is he capable of something different? My answer is basically yes. He is smart and adaptable.

Here’s him playing as a holding midfielder for Spain U21 against Albania. He went 141/151 (93%) passing on the day.

Perhaps more tellingly: I wanted to see how he fared outside of the Real Sociedad system, so I pulled all his numbers for Spain — going back to his youth days. In a big sample, he averaged 70 passes per game, and his completion percentage was 90%.

➡️ Ball-striking

By now you’ll know how beastly Merino is in the air, and that’s certainly true when it comes to to scoring goals on set plays. But to give you a general overview of his preferences, these stats (from Understat) should give you a sense of how he scores and creates:

Left foot: 146 shots, 11 goals, 99 key passes, 12 assists

Right foot: 15 shots, 3 goals, 71 key passes, 10 assists

Head: 76 shots, 7 goals, 19 key passes, 0 assists

There are no worldies in his portfolio that I’ve seen. In 2018, Theo Hernandez laid off a ball to him at the edge of the box and he nailed it into the corner, but that’s really it.

His long-range shots can be a bit demonstrative and blockable. By far, he is at his best when exploiting chaotic moments in the box. When there is a bouncing ball after a set play, or a rebound, or a deflection — he comes alive, has a great feel for space, nudges in front, and gets his money’s worth — often going for thundering blast.

Aside from his headers, his goal log looks almost entirely like this:

They’re fun when they hit, sometimes shaking the roof of the net.

➡️ Carrying & dribbling

Merino is a competent controller of the ball, and a non-voluminous (and often unexciting) actual dribbler and carrier. He picks his spots, shines in moments, but it’s just not a big part of his game or value — he doesn’t have that final layer of dextrous agility in his physical makeup.

His power-carries are solid, and he’s good at keeping his head up and spotting runners; he’s mastered the art of effective, well-timed scans in all situations. When on the run, I like his turns plenty.

When the ball was delivered behind him late in the semis against France, he adjusted nicely and helped see the game out.

In close control scenarios, he can do little nifty touches by anticipating his defender’s next move.

I watched one of his games against the Barcelona superteam and it was pleasing to watch him manipulate them with some sicko pull-backs.

Above all, he’s good at the little touches that buy him time in a 1v1, which explains why his dribbling percentage is nice and high (64.2%).

But he’s not going to drive at a lot of defenders more directly with the idea of beating them. If he lingers too long, or receives the ball in a crowd, he can definitely get caught out by snappier pressers. He is not Eze or Bruno.

➡️ Aerials

Merino is one of the most dominant aerial forces in the world. He’s certainly the most productive from the midfield position.

In doing so, he can show you the limitations of thinking in percentiles. By being a 99th percentile aerial battler, he’s almost double (!) the next-highest midfielder in La Liga.

While some players’ aerial skills are situation-dependent, Merino looks elite at all of them. He’s strong, smart with positioning, jumps high, tall, feisty, and has good technique. His teams use him as an outlet constantly; he’s not so much “indiscriminate” as he is “relied upon to do this all the time.” In the PSG tie in the Champions League, I watched their keeper Álex Remiro launch it 42 times in all.

Here’s Spain using him to generate a flick-on.

He’s a little like Toney in that he doesn’t win every single header but he wins almost every situation (leverage, progression, instability, etc).

In the box, I’m most impressed with his ability to generate power from far away. While Havertz is similar in open play, Merino’s got him beat here. He can head it from outside the six-yard-box, and should offer another Gabriel-level goal threat.

…he also puts a lot of care into the different situations, and can offer nice cutbacks and crosses via his head.

Here’s a stat from The Analyst:

Only six players in Spain’s top flight made contact with a higher percentage of defensive corners than Merino’s 10.2%, while only 11 players in the league recorded more than his 13 clearances from corners.

➡️ Off-ball runs

Merino is a really good off-ball presence, which has a lot of overlap with his brains and his work-rate. Like Havertz, he offers those selfless dragging runs, and is happy to sprint when there’s a switch to pull defenders away from his left-winger.

His false-9ing is weirdly good; here’s him serving as a backboard for a Spanish attack.

He’s also adept and active at feeling for pockets of space in the box, especially in bouncing ball situations.

👉 Out-of-possession

OK, enough with all that nuance.

Look at this motherfucker.

That’s him passing and ripping Dumfries, who isn’t slow — all while making sure his tackle keeps the ball in play.

…and again.

There are literally hundreds of these clips. This is because Merino won the most duels in Europe’s top-5 leagues by a margin, and that was a normal year for him.

(P.S.: Something worth investigating is whether or not there is an inverse relationship between such duel volume and passing percentage. Take a look at other players on this list — whether we’re talking Kudus, Bruno G., Palhinha, Lauritsen, or Bernardo (on Bochum) — and none of them are high-percentage passers given their position. In fact, some of them are particularly low. This makes sense: if you are constantly regaining the ball in loose, harried, advanced, congested situations, that is a less-optimal situation for passing percentage than just avoiding such duels and accepting passes in build-up. (There is also the possible explanation that your legs are tired). Is that an interesting question to you, and not just to me? Don’t answer that.)

His duels accumulate in all types (loose balls, aerials, defensive, attacking), and pure defensive volume isn’t in the 99th percentile so much as in the “above-average” category. There’s nuance to his game.

Merino is optimally prepared to literally hit the ground running at Arsenal. For six years, he has participated in a press that is, broadly, a more aggro version of Arsenal’s. Increasingly, he has become the primary conductor of it, directing traffic and timing jumps. Combine this with an immediate burst, a lot of core strength, and long legs, and you have one of the more active midfield presences in the world.

As opponent progression rolls along, he is perfectly comfortable on the left side of that 4-4-2 block, and is elite and dropping back into the box to defend amongst the CBs.

Defensively, there aren’t many players who would be more overpowered at the #8 with Rice.

What is also perhaps interesting, especially as his career rolls on and he becomes more rotational, is that he can be flexibly deployed across four defensive spots: #6, #8, 10, and probably even striker. I could even see him as a 36-year-old doing shifts back at LCB in Spain.

In the Euros game where he had his magic moment, he came on to help protect a lead — playing RCM with Fabian Ruiz and Rodri behind him, and pressing in the front-two.

When Germany leveled it late, he went back to LCM for extra time — and won it. This is the peace of mind that a manager craves. Basically, you’ll always be able to plug in a good defender late in games, and rotate players elsewhere as needed. This is also me implying that he’s an excellent late defensive sub for Ødegaard.

This work-rate extends to his recoveries, of course. These efforts resulted in four goals last year.

As far as defensive coverage goes, he’s an excellent rotator. This is where Zubimendi’s role is helpful — he is not a purely “fixed” #6, and can push forward when the situation calls for it. In these moments, Merino is obligated to notice and rotate behind to hold the fort. In theory, he provides Rice the opportunity to push forward more as he sees fit.

Are there any doubts about his out-of-possession game?

At Real Sociedad, at least, he’s not much of a sitter — he’s a jumper. This should be well-platformed by Rice. But with a Premier League game that is a touch quicker, there’s a worry that he may be swatting at air some more, and lose a little of his superpower. If he were to play a deeper role, though, I feel fairly confident that he’d be able to adjust to a more patient set of responsibilities, as needed.

He fouls a lot: 2.54 fouls per 90 would be among the Premier League leaders. He’s like Conor Gallagher in the way his hyper-aggressiveness usually doesn’t cross the line, but with a faster game, I could see him picking up a red or two — he doesn’t mind going to ground. It may also lead to cheap free kicks.

There are certain players he is less formidable against. I imagine somebody like Kudus will be a tough cover, as he is for everybody. I’ve seen Merino lose plenty of duels, but when he does, he is disruptive enough to slow down the play, change best-laid plans, and allow help to arrive.

In all, Wyscout tells me that his lost defensive duels led to zero (0) opposition goals last year.

👉 Injury history

He is not injury-prone, but not entirely injury-proof. He averages 32 league appearances per year for Real Sociedad, and he usually picks up about a knock per year.

👉 Positional forecast

Below, I’ve drawn up his most likely usage — which is also how I’d use him. Swap in Timber and Jesus as you see fit:

In possession

In terms of pure usage and locations of touches, nothing surprising here. I imagine his role to be quite similar to that of Xhaka in 2022/23. That’s how I’d use him, and that’s the role he’s been playing consistently for over five years.

A major difference will be the employment of his aerial prowess. If there’s a mismatch to exploit, or early build-up doesn’t look to prove fruitful, Ødegaard can drop into the pivot and Merino can go up high, await Raya balls, and go Bash Brothers with Havertz.

Against high presses, I’ve been seeing more of this lately — with three players in the midfield, a little closer together, drawing the press forward and creating space for the front-three. In addition to the more familiar looks, this may be in the offing, and give Rice the support he needs as he improves back here.

This 4-box-2 look, which was perhaps my fave from the entire season, is still in the cards. In this role, Jorginho played higher than Rice and was uber-direct, trying to hit Havertz and Martinelli as much as possible. This setup is some of the opportunity cost for me, and why I was anxious to get a top 5% passer in the world, tearing apart a Liverpool. Merino is not really that, but he can capably do this.

With a Rice/Merino pivot, you’ll want to see some updates for additional support and line-cutting: Ødegaard dropping more, Rice getting more incisive, Timber or Calafiori turning into a metronome, etc. Otherwise, Jorginho or Zinchenko will probably butt their way back into lineups. Ødegaard is very much the solution to that, but the problem is that he’s very much the solution to the press, too, and those are too far apart to sustainably do, every time, in every match. There’s a balanced path forward.

I’d expect the 8’s (Merino and Ødegaard) to have more interplay than we’ve seen of late.

Out-of-possession

A week or two back, I drew up a 4-4-2 block with Timber at LB and Calafiori at defensive midfield, showing a disgusting look that could be used late in games. I was kind of fucking around, but hundreds of people on Twitter educated me on various obscure terrorists as a result. I regret nothing. The funny thing is this: the more likely block — with Merino and Rice in the middle, and 4 CBs behind — is every bit as tough as that one.

Other roles

Defensively, he is capable of playing #6, RCM, aforementioned-LCM, and even as an emergency-depth backboard striker, at least in my opinion.

In attack, I see him as a pure box-to-box #8. He can play RCM as needed, flinging passes forward, and his angles look fine out there. I have less confidence about his tempo-and-turning at #6, and he would be deprived of his aerial abilities up the pitch. I don’t fully write it off because he’s smart, but there would have to be some growth and a really active pivot partner (like Zinchenko or Ødegaard).

Like Havertz and Jorginho, I think he’s the kind of player that coaches get addicted to. I’d expect him to play a good amount.

Let’s wrap it up, shall we?

📉 Bear case

In a downer future, Merino’s ground coverage is less impressive in the Premier League, which strips him of some of his superpowers. He racks up fouls, and even gets a couple of double-yellows. This then lends importance to his other, in-possession qualities, which don’t sparkle upon re-entry to the league: the high losses compound, and they are not compensated by enough active threat on the dribble or via the pass; not only that, they kick off a few counters the other way. All of this leads to some stubborn issues with the stalling of dynamic progression, a left-side that never fully gels, and mid-block issues that persist because there aren’t enough big dribblers or passers on the pitch. Instead of a key cog, Merino becomes a veteran rotational piece, one who may grab minutes from younger players or otherwise block some signings, and Arsenal’s ceiling remains intact.

📈 Bull case

A bull case can be made for Merino in the form of a game against Benfica.

In a Champions League tie, Merino and his teammates were set to face a supremely talented, hipster young duo: João Neves (who is off to PSG) and Florentino Luís (who has a limitation or two, but also has a whole lot of talent and production).

Merino made them his sons.

He ran everywhere on the pitch, committing 98 total actions, and jumping into 33 duels overall.

At 5’, he caught Luís napping at the back post and headed it home.

At 15’, he worked with his side to manipulate the Benfica line on a free-kick, offering three false starts, pulling the line 10 yards down, then catching Neves flat-footed and ripping behind him for a goal. (This one deflected off his arm on the way in, so was eventually disallowed by VAR.)

By 21’, he was switching play out to the wing for an assist to make it 3-0 — the ball had gone into the net four times by this point. I always talk about Arsenal need these passes to be quicker.

It could have been 5-0 within 30 minutes. The midfield battle was so bad that Luís got the dreaded early hook at 31’.

This, really, is the value of somebody like Merino. There are buzzier players (and Neves isn’t just buzzy — he’s really, really good already). There are younger players. There are players who may preserve their value better. But if you put them head-to-head, and ask them to play football against each other, Merino will often prove himself superior.

He is simply better than players in the reported price range, and also currently better at football than many players going for 1.5-2x his fee. That may not hold true in three years, but it’s true now.

There are other factors to consider. As we are Junior Arteta Sickos, we must start with the out-of-possession side.

Last year Arsenal had a solid claim as the best out-of-possession side in the world, though there were other contenders. This year, the plan is to take some of the minutes given to Zinchenko, Kiwior (at LB), and Jorginho (at 6), and hand them over to the likes of Calafiori, Timber, and Merino. Call the ambulance, but not for us.

On top of that, there were games where White was clearly battling a knock, but he couldn’t rest because his backup was Cedric. There were games when Rice was backed up by Myles Lewis-Skelly. They managed to make fucking Ødegaard tired against Fulham. It was no coincidence that this team flagged at the end of December, when fixtures piled up; then, they got some time off, and came back electric. A flexible, trusted midfielder would do wonders here.

There are other factors to consider in the “plus” column:

If you do the kind of big swing I was initially targeting (FDJ, Bruno Guimarães, etc), that solidifies a three-man midfield, and would make minutes hard to come by for the likes of Ethan Nwaneri (and Lewis-Skelly). This move creates a more modular setup where Nwaneri can settle in at the speed he determines.

I think it’s helpful to take a more expansive look at squad lists, and look less at “positional cover,” and more at “profile cover.” A player doesn’t need to slot in at the exact same position to effectively cover a starter; their qualities need to be covered, however. For instance, Jorginho and Zinchenko were essentially spelling each other last year … at different positions. If Saka misses time, Arsenal will be light on 1v1 gravity, dribbling, and playmaking — that needs to be offset somewhere, but it doesn’t necessarily have to be at RW. As such, Merino is great Rice cover, even if he never plays in the #6. With Jorginho and Partey in the squad, Arsenal are perilously light on midfield space-eaters. Without Rice, you feel bad about the physicality of a Jorginho/Ødegaard/Vieira midfield, for example. Merino basically fixes that. Jorginho/Ødegaard/Merino is all good, and so are some other permutations.

He is also, in his own way, Havertz cover. Especially down the line, it got hard to picture lineups without Havertz in them — especially when you’d like to go long or take advantage of set plays. Merino covers that, too. In many ways he’s the more practical version of what Arteta sought with Havertz last year.

To make a convoluted point: I think Xhaka is a better Xhaka than Merino could be. Merino wouldn’t be able to put together the ridiculous progressive numbers that Xhaka did at Leverkusen. But, I also believe the inverse is likely true — Merino is a better Merino than Xhaka. And in 2022/23, Xhaka was essentially doing a Merino impression. Now, we get the real thing.

Perhaps most importantly, he offers help and mature stability to the left side. I feel #nice about his positional nous when combined with Calafiori and Timber, and that triangle is looking like a quick, snappy, aggressive 1-2 machine. His left foot helps go wide and whip crosses. Like I said, in a vacuum, I’d like a little more flair, overlaps, and burst here. But there are going to be some one-touch passes forward to Martinelli in space that get people standing.

At the outset, I said I wanted the highest-echelon passer here because “I’m concerned about lineups without Jorginho and Zinchenko in them, and I’d like to add somebody who can stand on the ball and dictate play if needed.” Well, I recently estimated how Ødegaard fared when he dropped low to receive, and the numbers were astounding: he averaged more progressive passes per 90 than Rodri (11.75 to 11.5, on 32 fewer touches per 90); 19% of his passes were progressive, compared to 11% for Rodri; he logged 94% short completion. Ødegaard dropping a bit, and splitting the pivot with the likes of Timber, Calafiori, and Merino, may offer all the benefits of a huge outlay at #8. You just have to make sure it’s balanced so it doesn’t lead to overexertion.

Given his background, experience, age, language skills, and role, Merino offers a rare ability to adjust quickly.

This move preserves a lot of budget and flexibility for future moves, preferably in attack. I think, and hope, that advantage will be used to the maximum in the near future.

We can pick nits.

I, for one, think it’s mandatory that speed and dribbling get addressed from here; in fact, that bar is raised after a Merino signing, and you need somebody who just overwhelms opponents with their speed and 1v1 ability (hey, why not the #2 worldwide at duels won, Kudus? 🙃). In a hypothetical, I’d subtract 5% of Merino’s capacity in the duel for +5% of extra power and manipulation on the ball. If this gets close to, or above, say €35m (£30m), I get less comfortable with the value and opportunity cost.

But here’s one thing I’m more sure of: the more you watch Merino, the more you will like him. For another, it’s increasingly difficult to see how teams are going to score against Arsenal next year.

After the season, we wrote a huge piece called “5 Ways to Improve Arsenal.” Merino offers fortification to the first two objectives we listed: a) Improving Plan B (through the left), and b) Increasing Risk Tolerance in the Middle.

Sales have been good (at least so far). As long as the wages and fee on this one remain reasonable, and the remaining funds are used to proactively address the final three improvements needed (basically: speed, ball-striking, and hopefully big passes), it’s hard to argue with a move like this.

Happy grilling everyone.

❤️

Dude! What you're doing is in the 99th percentile Billy. The stats, writing, the wit. Top fucking class! Keep going 💪

We are so lucky to have you writing about our team. Every time, I learn more and more about football but also about writing and thinking clearly. What a read… take a bow!