The Arsenal full-back revolution

The tactical impact of Calafiori and Timber. Plus: Don't forget about White; Merino and the evolution of the left side; what Ødegaard's re-entry looks like; the upcoming slate; and a lot more

The first thing to know about Mikel Arteta’s full-back revolution is that it’s been in the works for some time.

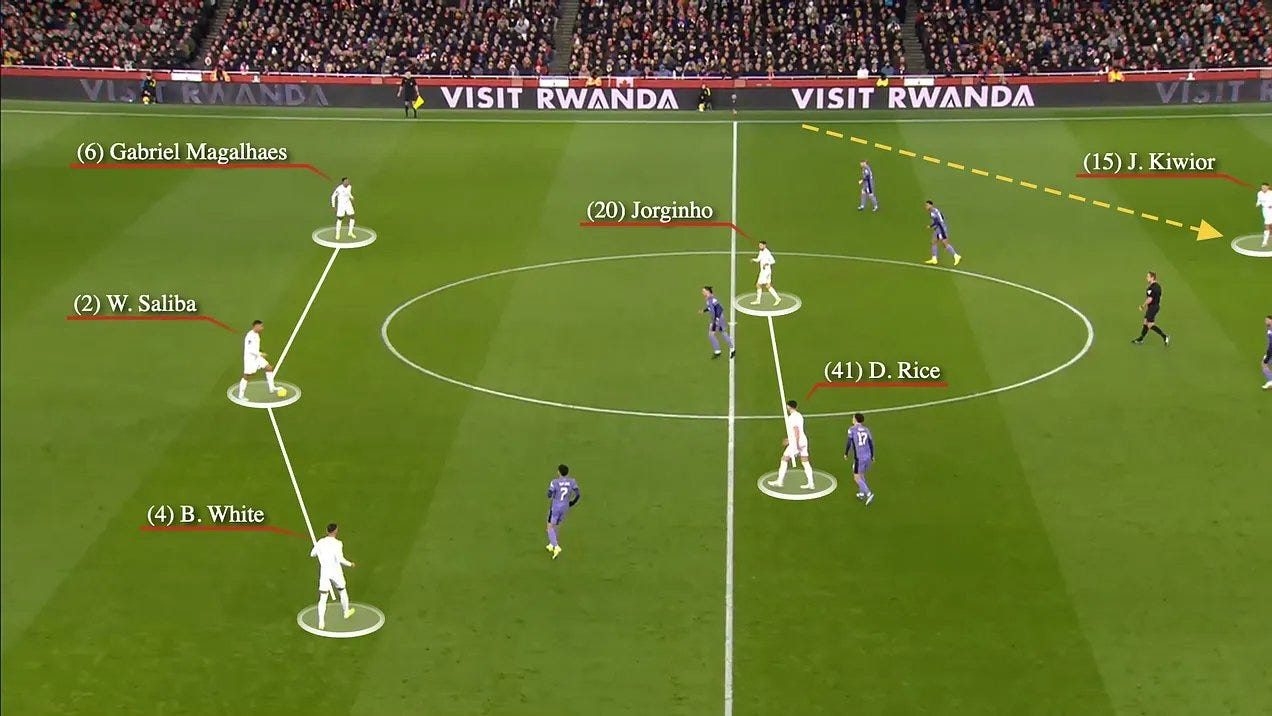

Two seasons ago, Oleksandr Zinchenko was signed to play an inverted, quasi-midfielder role, driving progression alongside Thomas Partey — which transformed how Arsenal would play. The basic, nonrevolutionary idea was to borrow a player from the backline so another attacker could be flung forward. That January, Jakub Kiwior was signed with a curiosity (if not a certainty) that he’d deliver some interesting attributes to the position, as well. Last season, Jurriën Timber joined to provide the next step of evolution, but all we got was a brief, intriguing cameo.

In lieu of Timber, we continued to see the available players deployed in interesting ways. As the steady hand of the position — and by “steady hand” I partly mean “the one who is usually healthy” — Benjamin White has outlined the difficulties of playing the position somewhat famously.

“Playing full-back the way he wants is, I think, completely different to any other manager.

To play full-back for him, you've got to be a centre mid, a centre-back, a winger, a No 10. So, it's been about developing the whole of my game, rather than just as a full-back or a centre-back.”

White may often be described as a “hybrid centre-back” to differentiate him from a typical overlapper like Andy Robertson. But at the time of that article, guess who was leading the league in overlapping runs? That’s right: White.

“I'm doing all his running," he jokes when that statistic is put to him.

“That's what I'm there to do. I'm there to help him get into positions where he can do what he is so good at. If that means I have to do more running, then that's what it is.”

While his role has been relatively steady since Saliba joined the squad, it has carried some tweaks on a matchup-to-matchup basis.

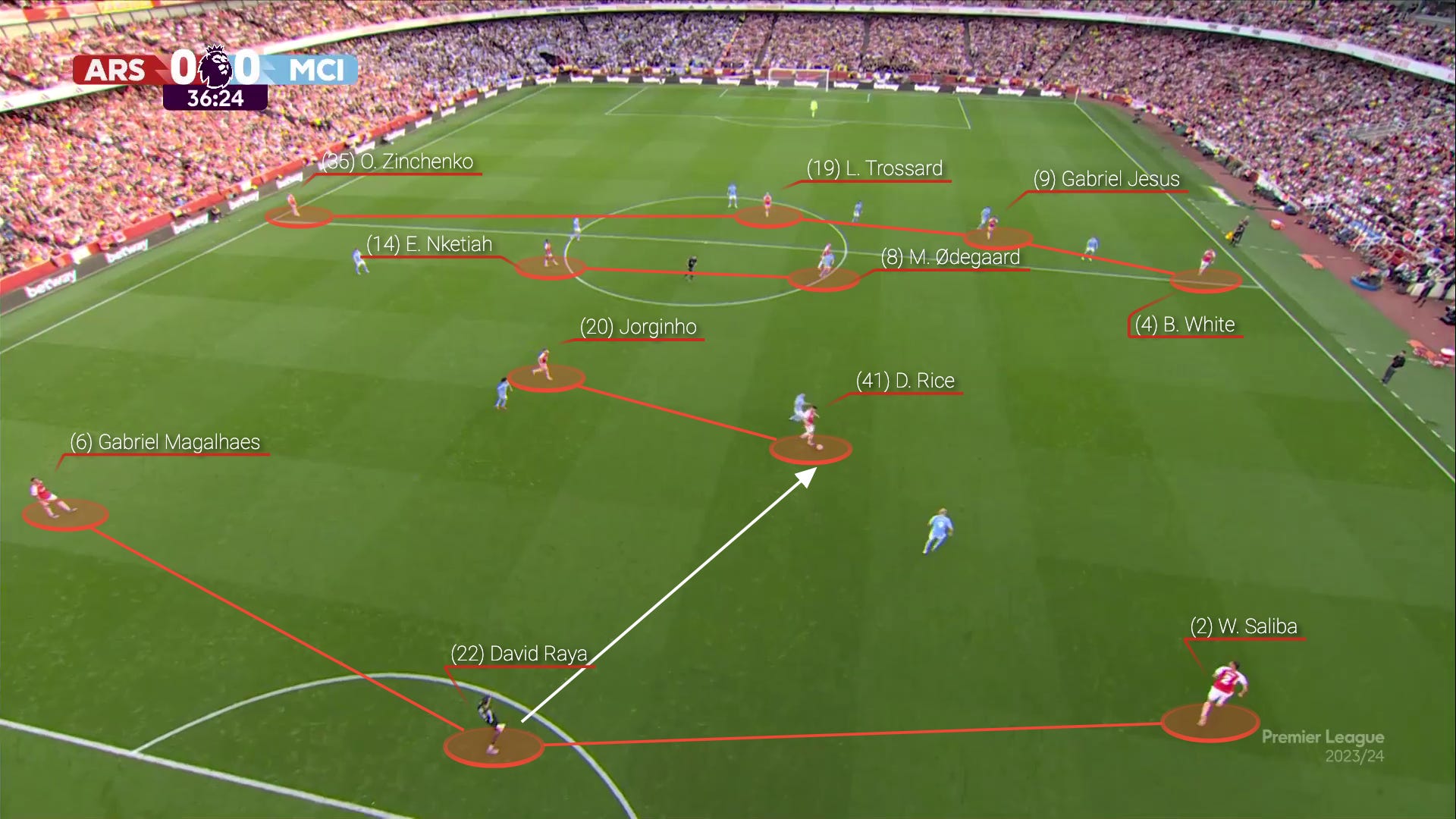

In the first (victorious) matchup against Manchester City last year, he was often pushed up high as a winger, which pulled their wings (Foden, then Doku) down to defend, hurting City’s ability to attack with enough force.

While he sprinted down the line, Tomiyasu subbed onto the other side, and helped deliver the winning blow.

That was not the only iteration. For a spell last year, we saw White finally inverting into midfield from the right, in a pivot I dubbed the “White Rice.”

With Ødegaard dropping to receive at times, this allowed Kiwior to play a more straightforward iteration of LB. While this may not have been the ideal giant-killing setup, Arsenal were able to play overmatched opponents off the pitch.

But the more portentous developments came from the left.

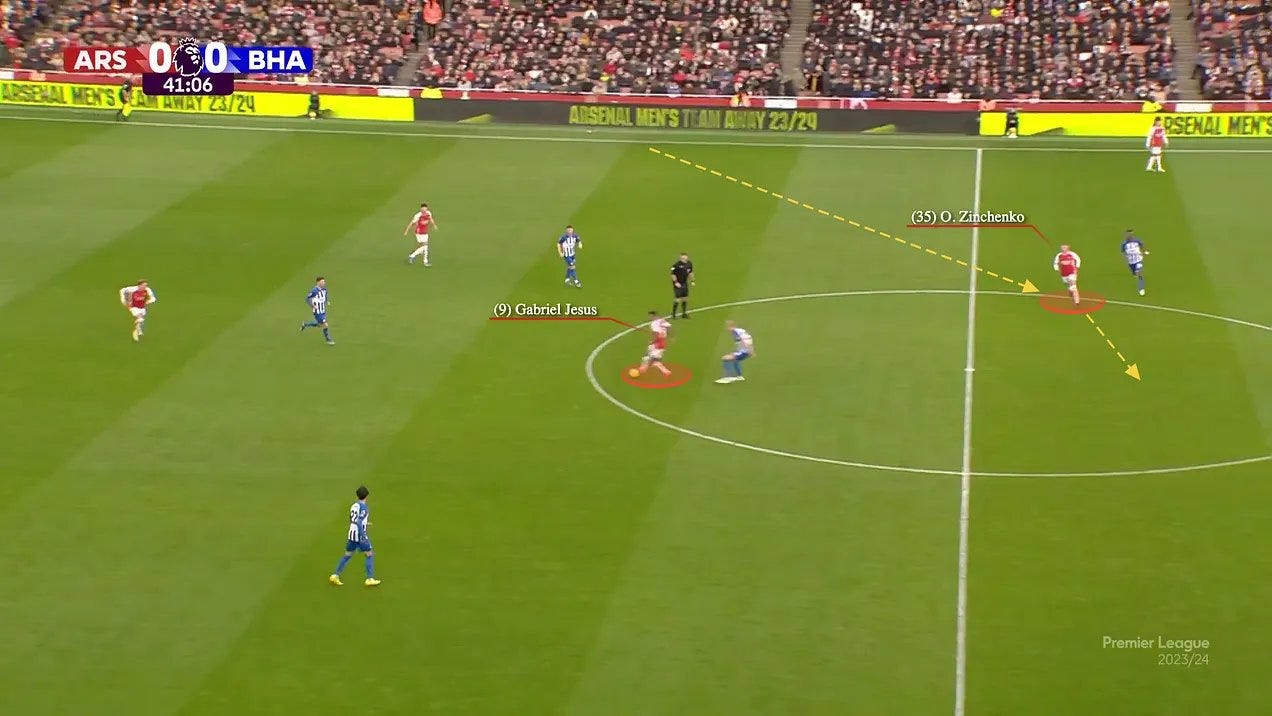

We’ve seen Zinchenko in his normal pivot role, but we also saw him float above the midfield and look to show himself as the free man — which wasn’t unexpected given his international history in the midfield, and his generally vagabonding ways.

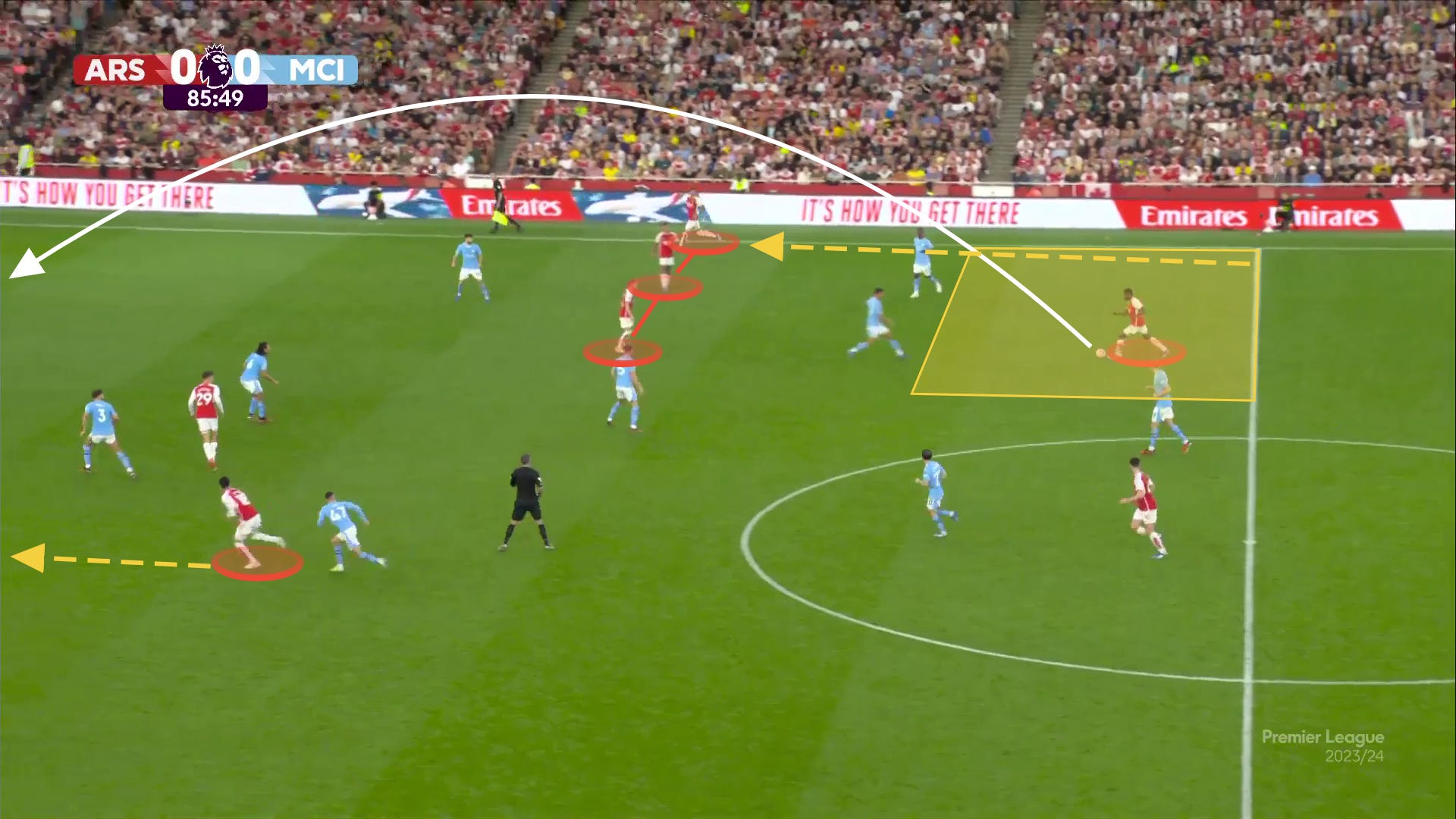

There were also some of the floating ‘target man’ style runs that we saw Tomiyasu do against City.

As the team opted for more of a double-pivot, the left-back (often Kiwior or Tomiyasu) would roam up from the left-back position, and into the type of spots that Xhaka would have filled in years prior. This was a great unlock of last season, as it allowed Rice to stay close to a more athletically-limited midfield partner, shielding counters in the process.

But the most telling prototype was Roamiyasu. He’d go outside, inside, up to the wing, and drive forward into the half-space. There were matches where he was the most fun player to watch.

He was trusted with this role because of his tactical brains, ability to cover space, and two-footedness. But he has some natural limitations too: he’s still technically a righty, can be pressed through the middle, isn’t the most agile carrier, and, of course, has trouble staying fit.

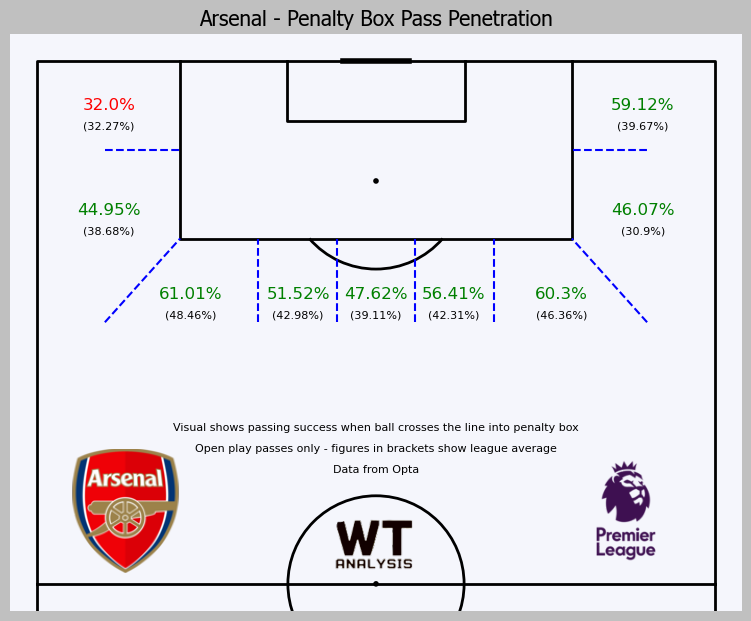

Throughout the season, there were two recurring issues at full-back: a lack of reliable surge in our attacking threat on the left — as shown by the below chart from WT Analysis, which I seem to post every week — and a lack of rotation on the right.

Which brings us to this year.

🚪 Enter Jurriën and Riccardo

One signing.

One “like a new signing.”

What unites them? According to Arteta:

“They are two players that have a football brain, the intelligence, the quality and adaptability to occupy different spaces whether attacking or defending,” he said. “That gives the team a different dynamic and makes it unpredictable for the opponent to defend certain ways. Both are huge personalities too which I love.”

There is one non-negotiable.

“They have to have one in common – they have to love defending first. Because they are defenders, then after that they have qualities to add, that’s great.”

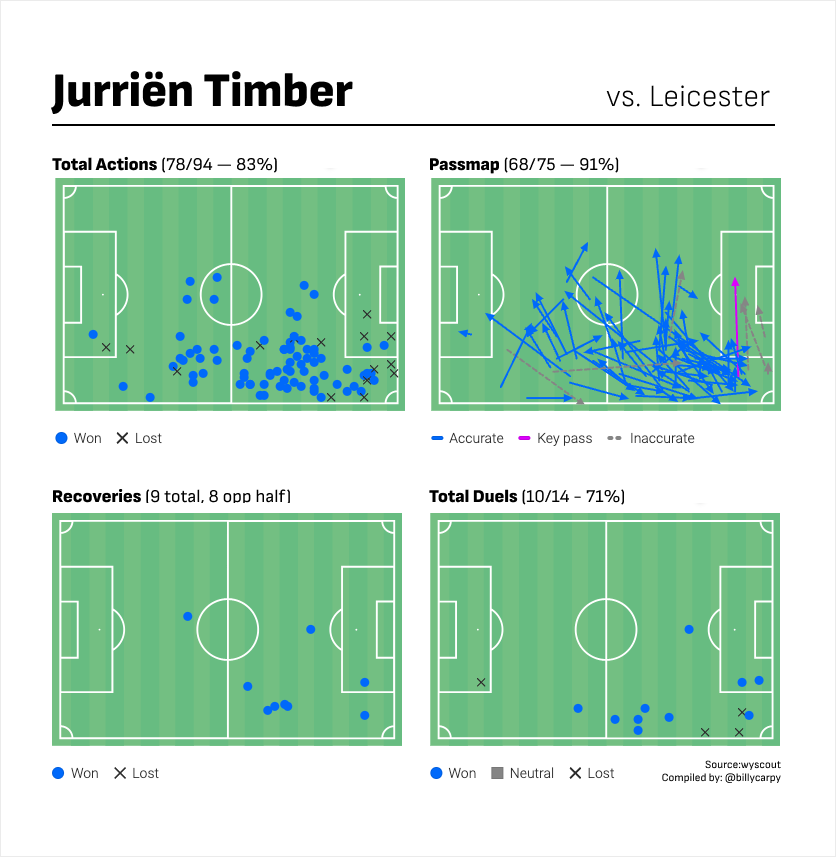

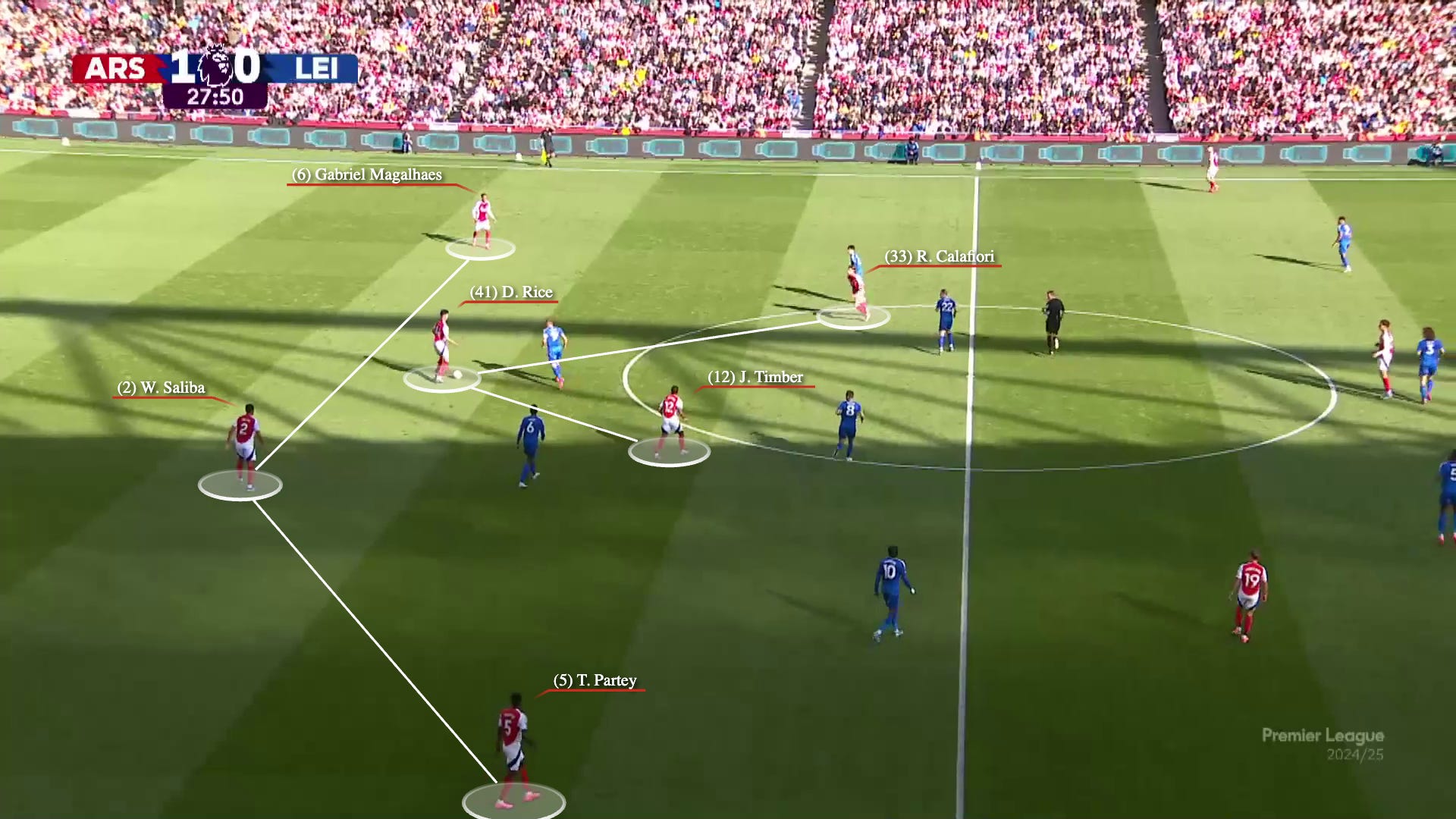

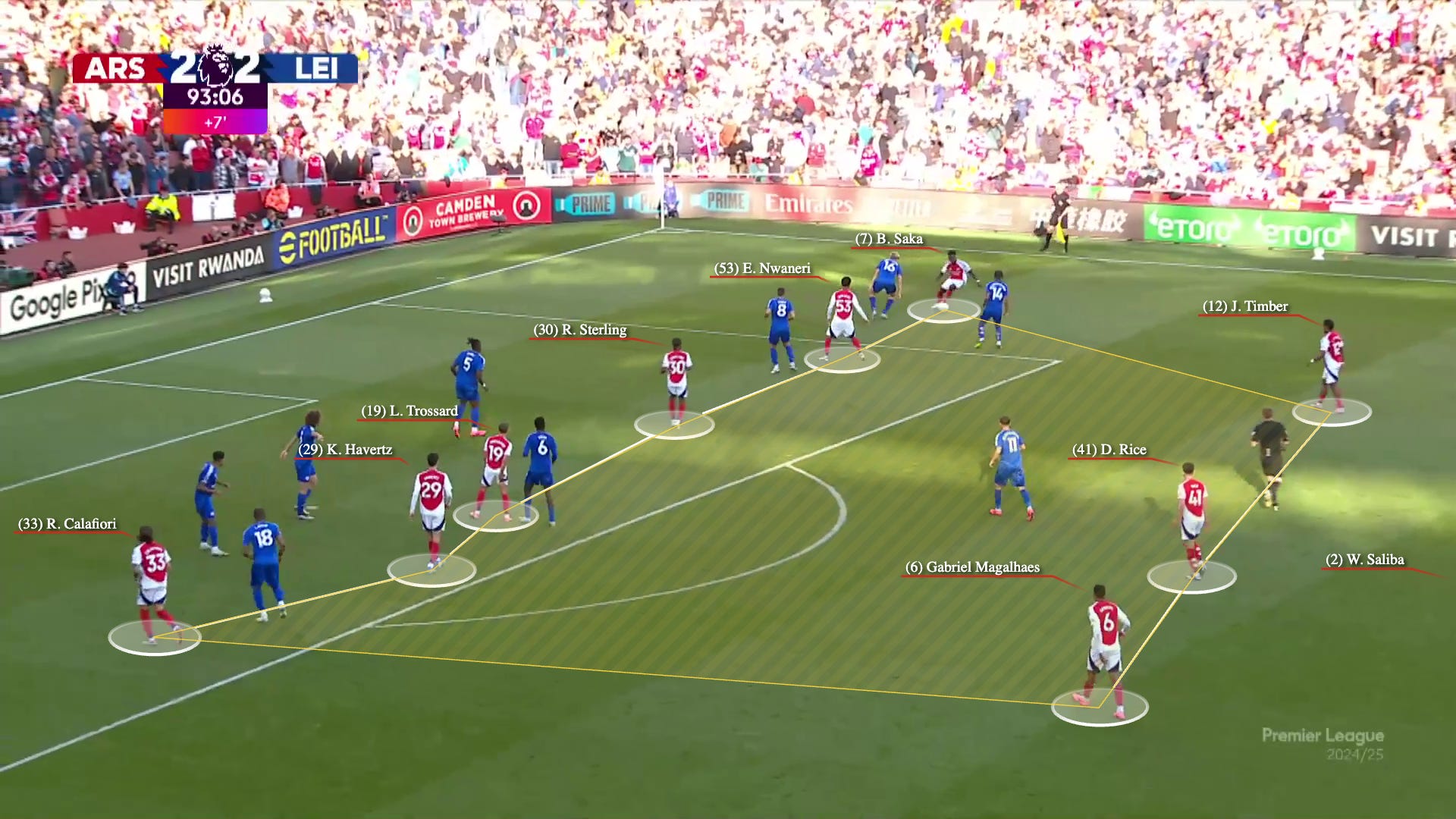

The new partnership was most visible against Leicester. Let’s start with Timber.

Managers are almost always effusive about their players. If you want real insight, you have to glean the subtext of their quotes, and try to mine them for specificity. What kind of themes do they harp on regularly with a player?

For Timber, every Arteta quote seems to have the word “leader” strewn throughout. From July:

“He has a great environment around him and hopefully that will make him a better player. He is a leader. He loves to be on show and a big presence in everything that we do. He is very vocal and extremely gifted technically. He is a great addition to the team.”

…and now:

When asked specifically on what Timber is like as a character, Arteta replied: "A leader. A guy that is constantly thinking how can I help others and bringing great quality to everything that he does.

There were others.

For Calafiori, Arteta focuses on different qualities.

“He landed with the biggest smile on his face. He’s got this energy and aura around him. He’s very likeable and he’s a fighter, a player that wanted to play in the way we want to play and he’d do anything for the team. When you have those qualities, a lot would have to go wrong for you not to succeed.”

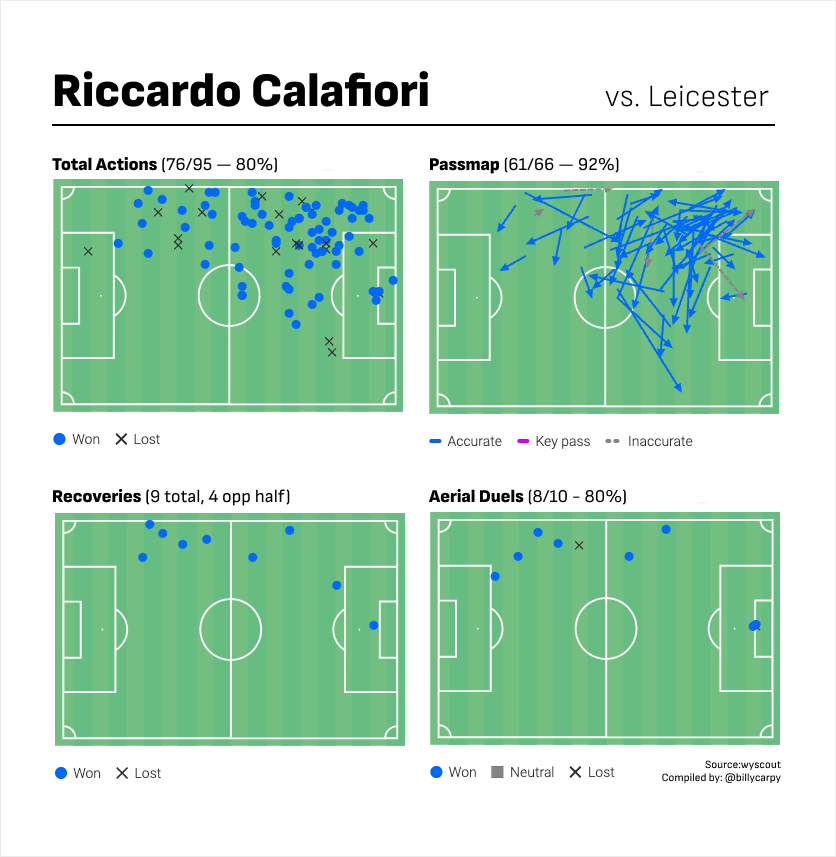

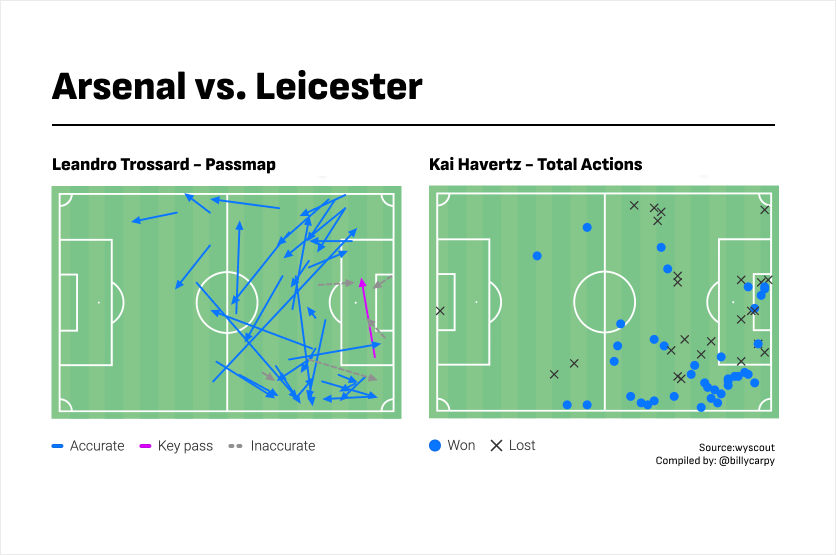

While Timber and Calafiori had a similar amount of passes against Leicester, Calafiori has generally inverted more. While Timber is often a technical minimalist, showing calm confidence in his actions, Calafiori has been a tornado across the pitch.

Let’s discuss how these new additions have impacted how Arsenal play. We’ll start with some descriptive work, and then get into the #analysis.

👉 In build-up

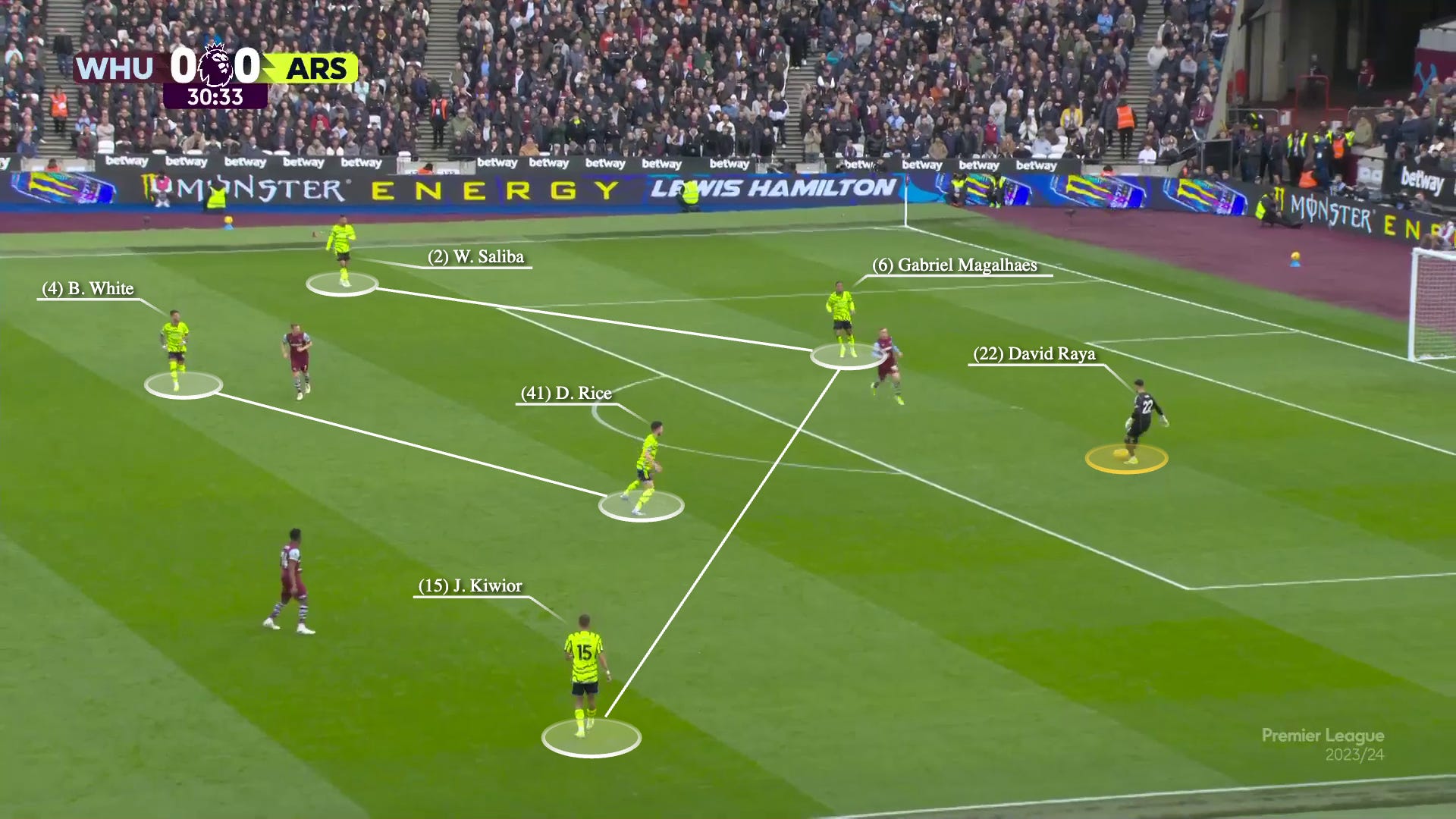

One of the largest questions still hovering over the Arsenal season is the build-up. Last season, Arteta was often forced into a tradeoff: should he reinforce deep progression with a player like Jorginho or Zinchenko, or reinforce physicality with a Havertz or Kiwior/Tomiyasu?

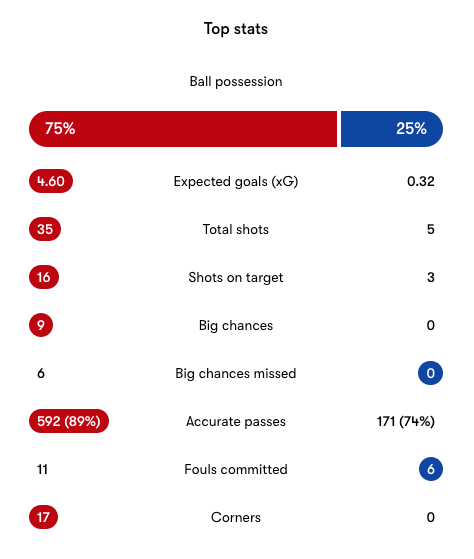

The early part of this Arsenal season has been spent, and will be spent, probing for a solution that involves fewer trade-offs. It’s not fully settled yet: against Atalanta, for example, Raya wound up blasting it long over and over again, and he still leads the league in launched goal-kicks by a margin (though there are some mitigating factors, cough PGMOL cough). With more steady build-up structure and personnel, the hope is that Arsenal can keep opponents guessing. Unpredictability, you know.

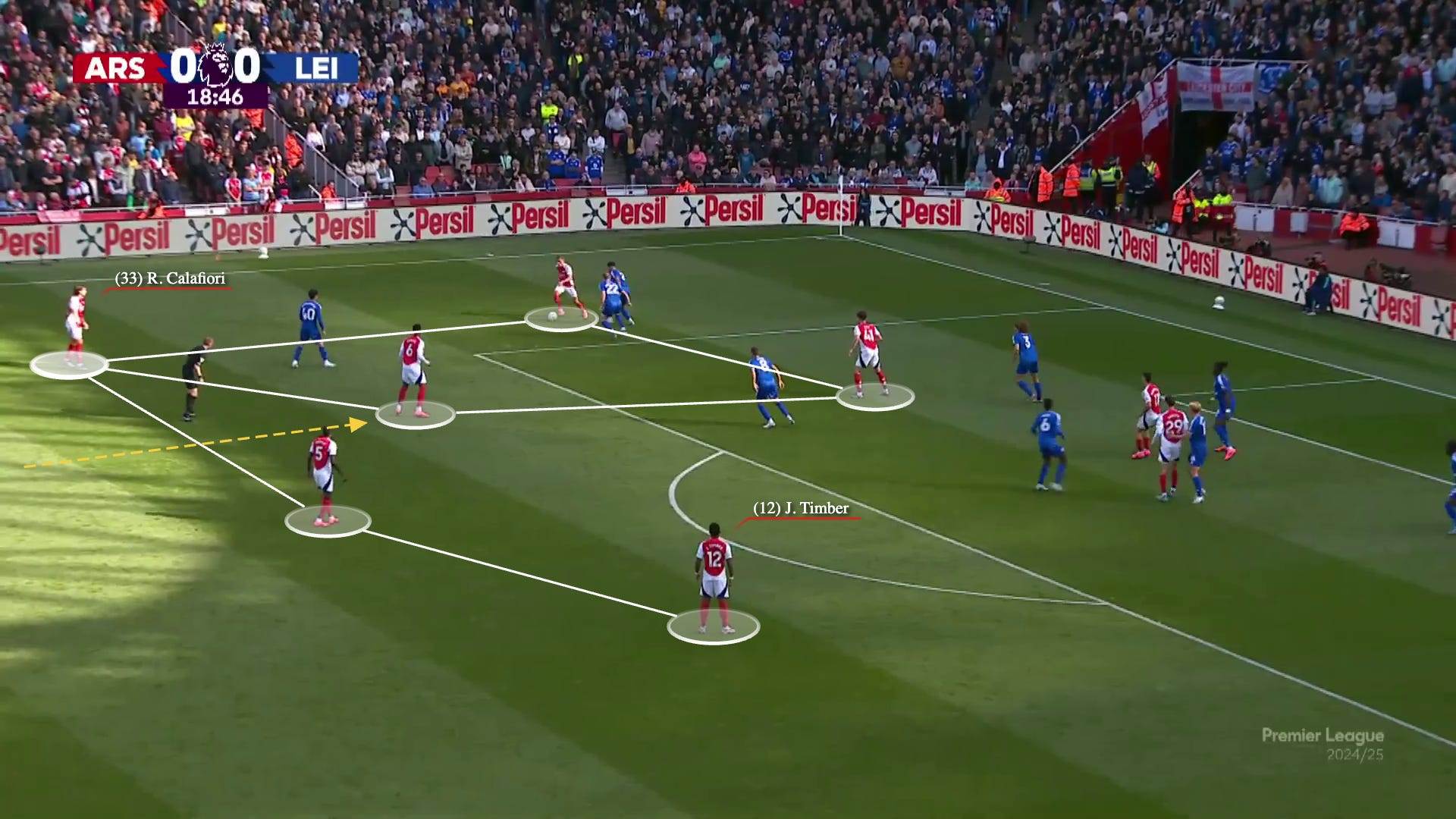

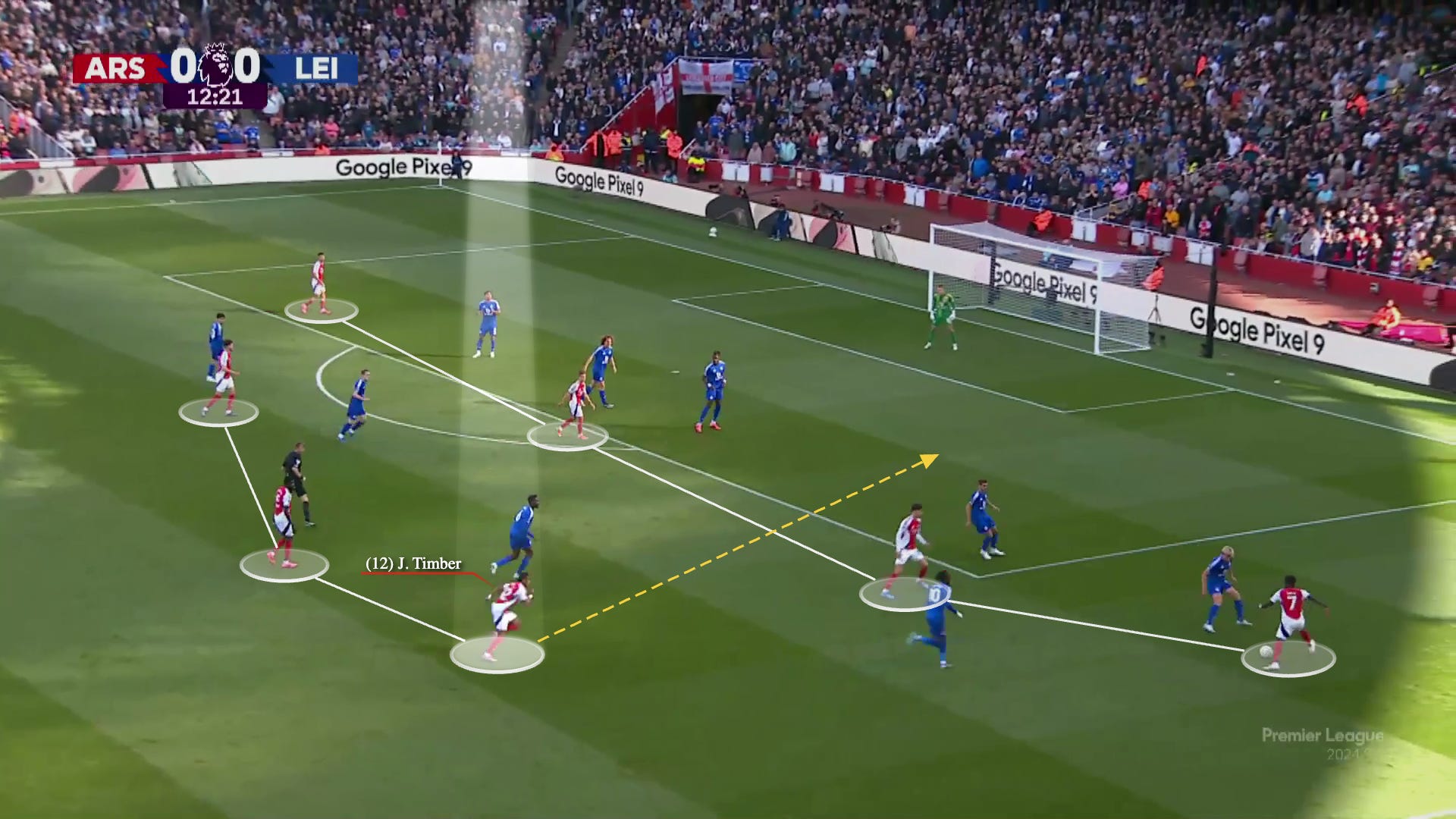

Some of the outlines may be peeking out. The most straightforward way to look at it is this: both full-backs went inverting through the middle in a situation where Partey dropped to right-back (where he started last weekend) and Rice dropped low. Fun, fun.

That kind of rotation — in which both full-backs were available through the middle — barely ever happened last year.

That will nonetheless be a more opportunistic look, though.

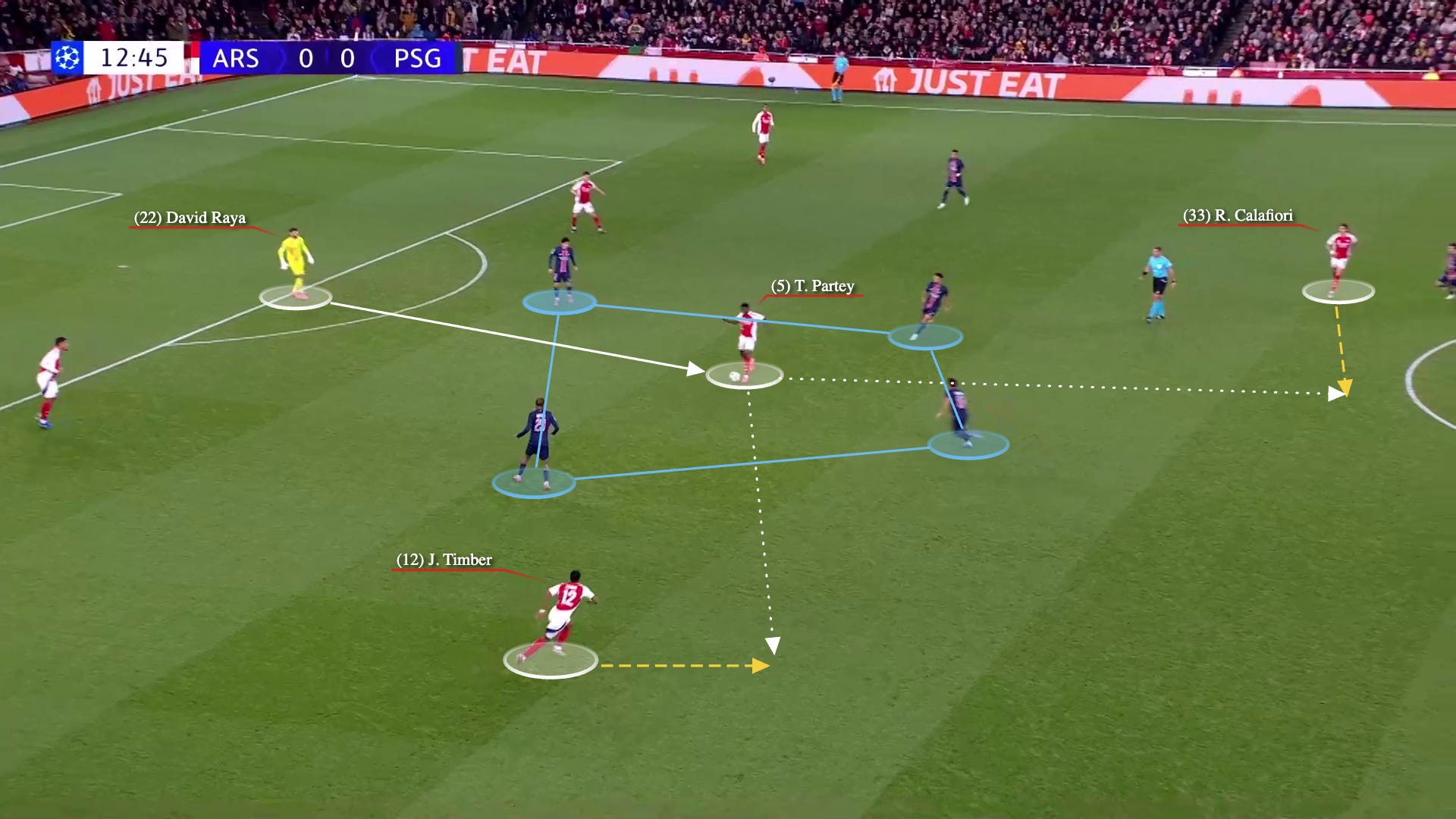

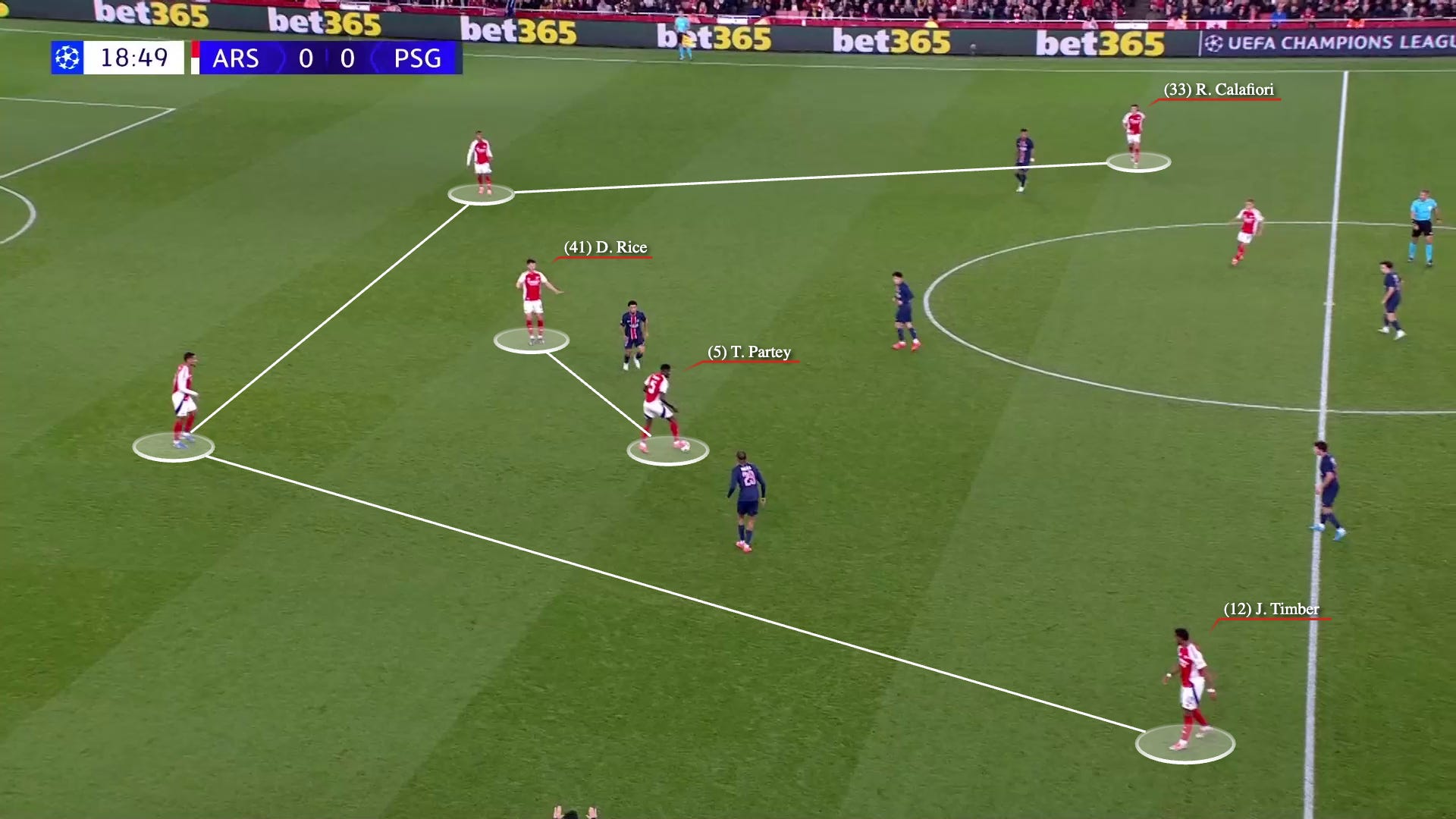

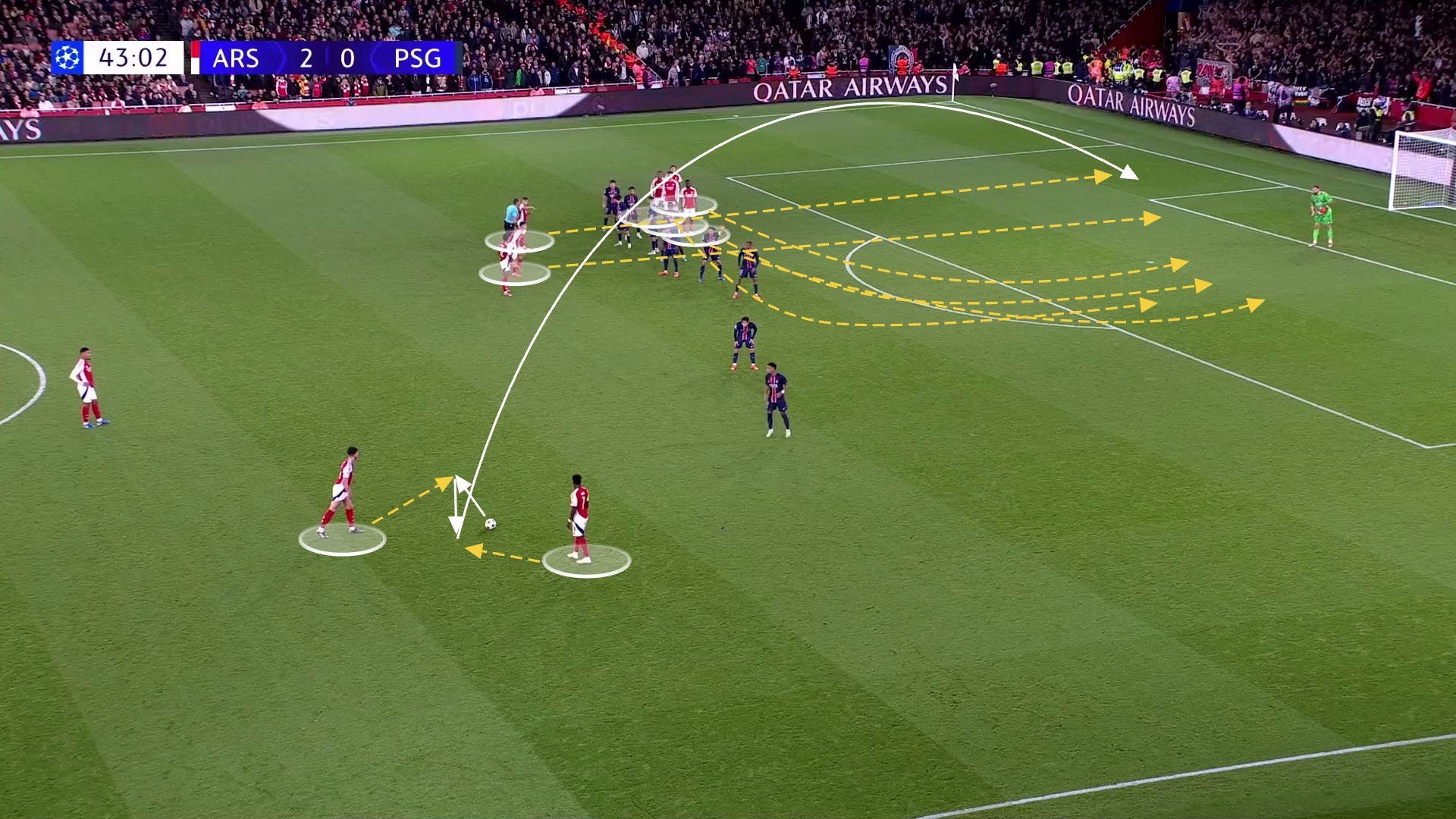

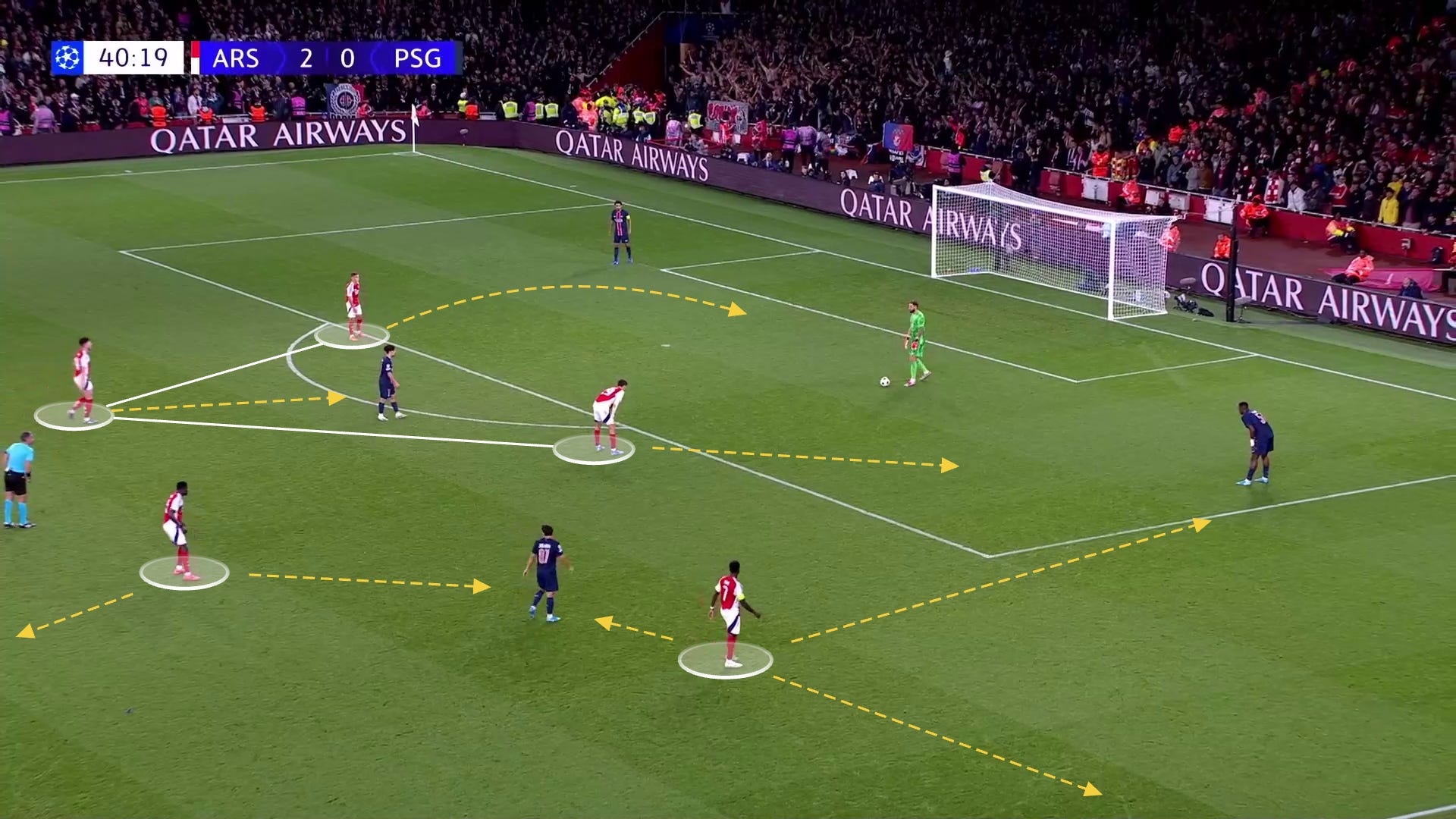

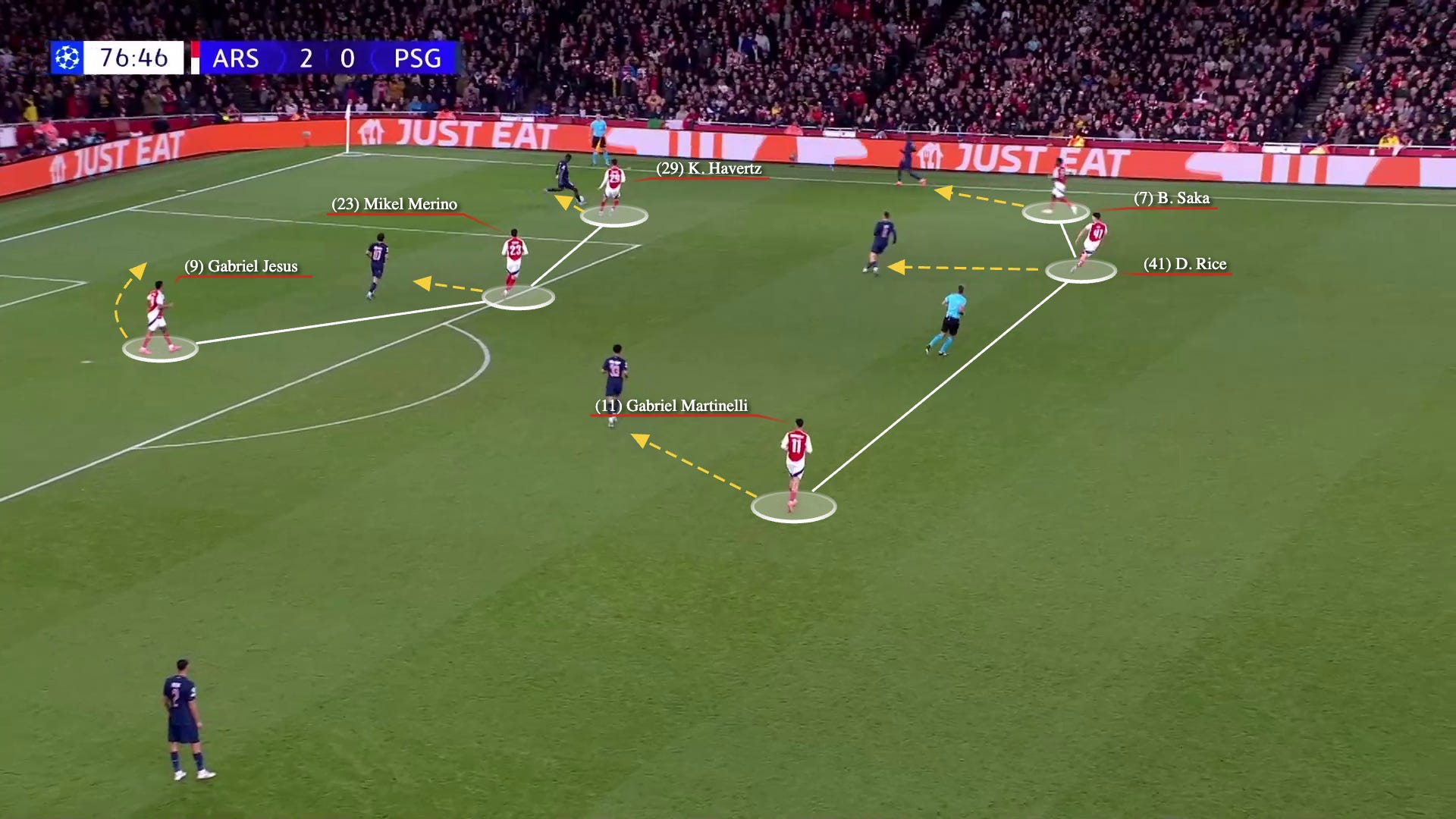

The real potential shows here. In this moment, PSG were pressing as normal, Raya stepped on the ball in his normal “CCB” position, and the CBs split out wide. Rice drops to show an option, and Partey makes himself available through the middle.

As soon as Partey drops, the PSG diamond converges upon him. But they are overburdened because two full-backs have shown themselves for the ball, and darted into lanes for availability.

The defenders can’t close down in time. Timber is left free to carry up the majority of the pitch, and we are greeted with the most welcome of sights: a genuine Saka 1v1, however fleeting.

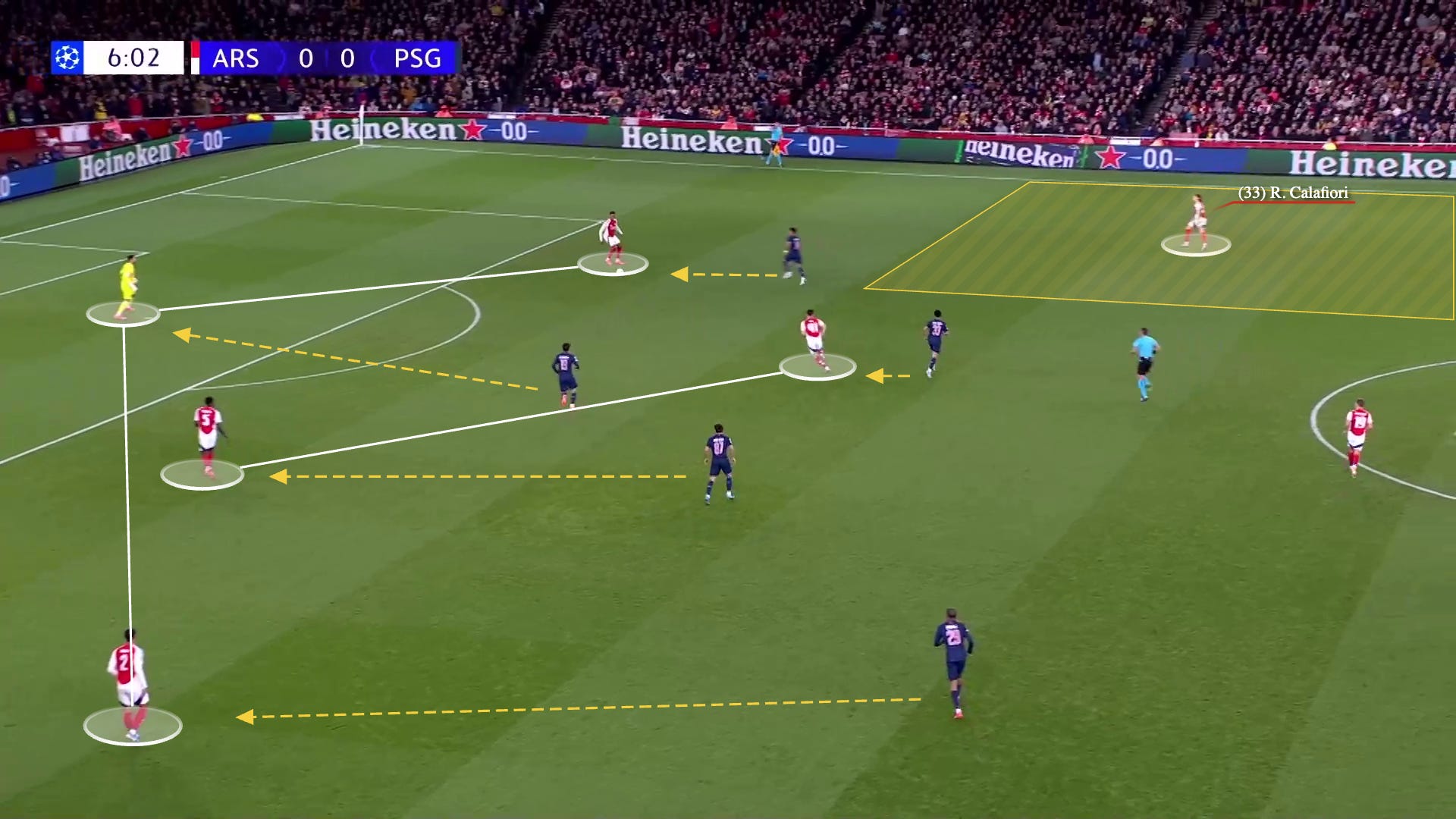

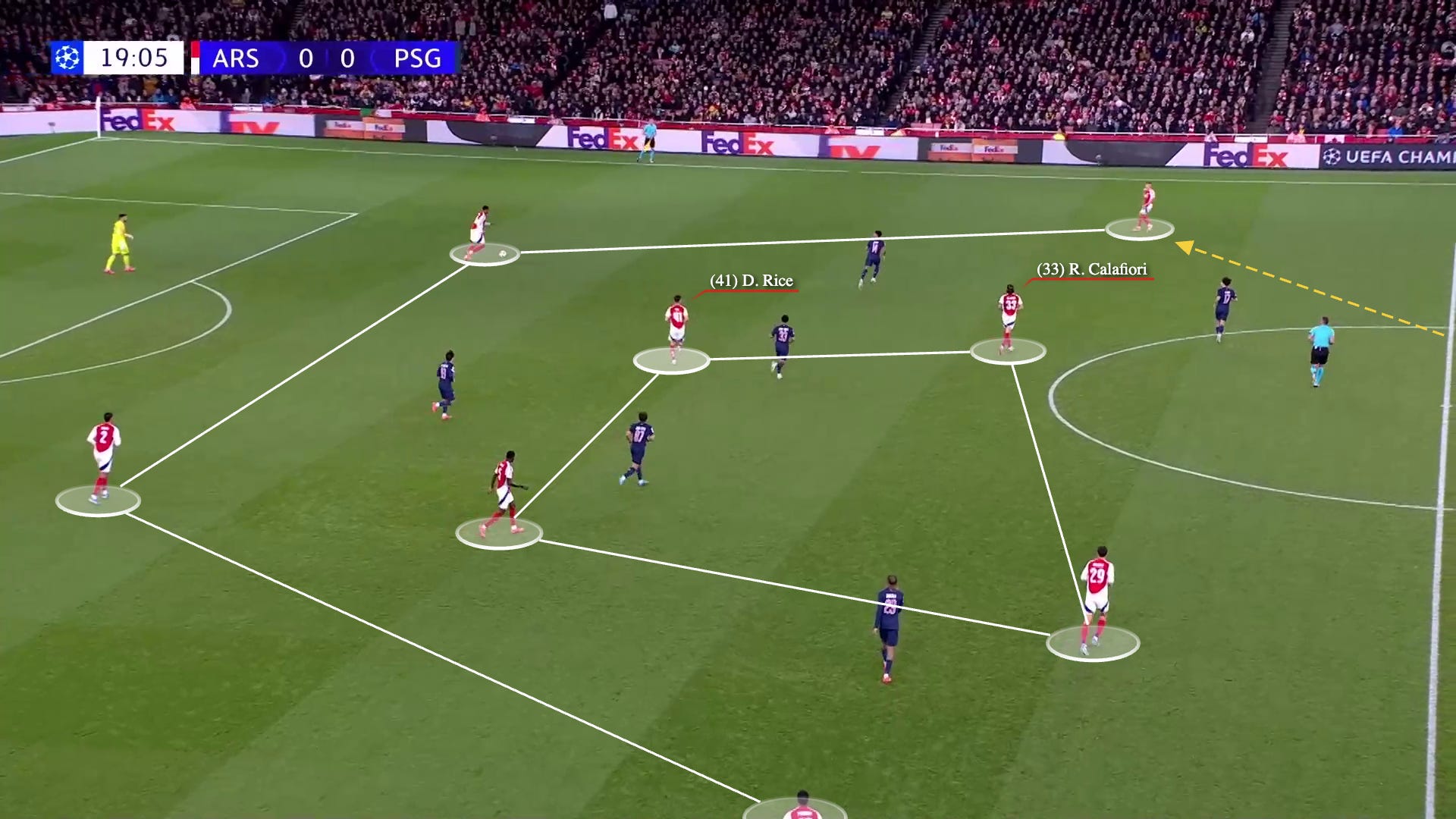

Here, you’ll see a couple of concepts in play. The CBs line up extra-wide, and Raya is a credible threat from GK. Because of that, PSG is left with a choice: they can shuttle another presser forward, and leave their backline exposed to Havertz. Or they can leave a full-back free. This kind of “damned if you do, damned if you don’t” decision is what Arteta is trying to bait with the likes of Raya, Merino, and Havertz. So far, it has tipped too far into the long-ball direction.

Here, the see-saw of threats looked good.

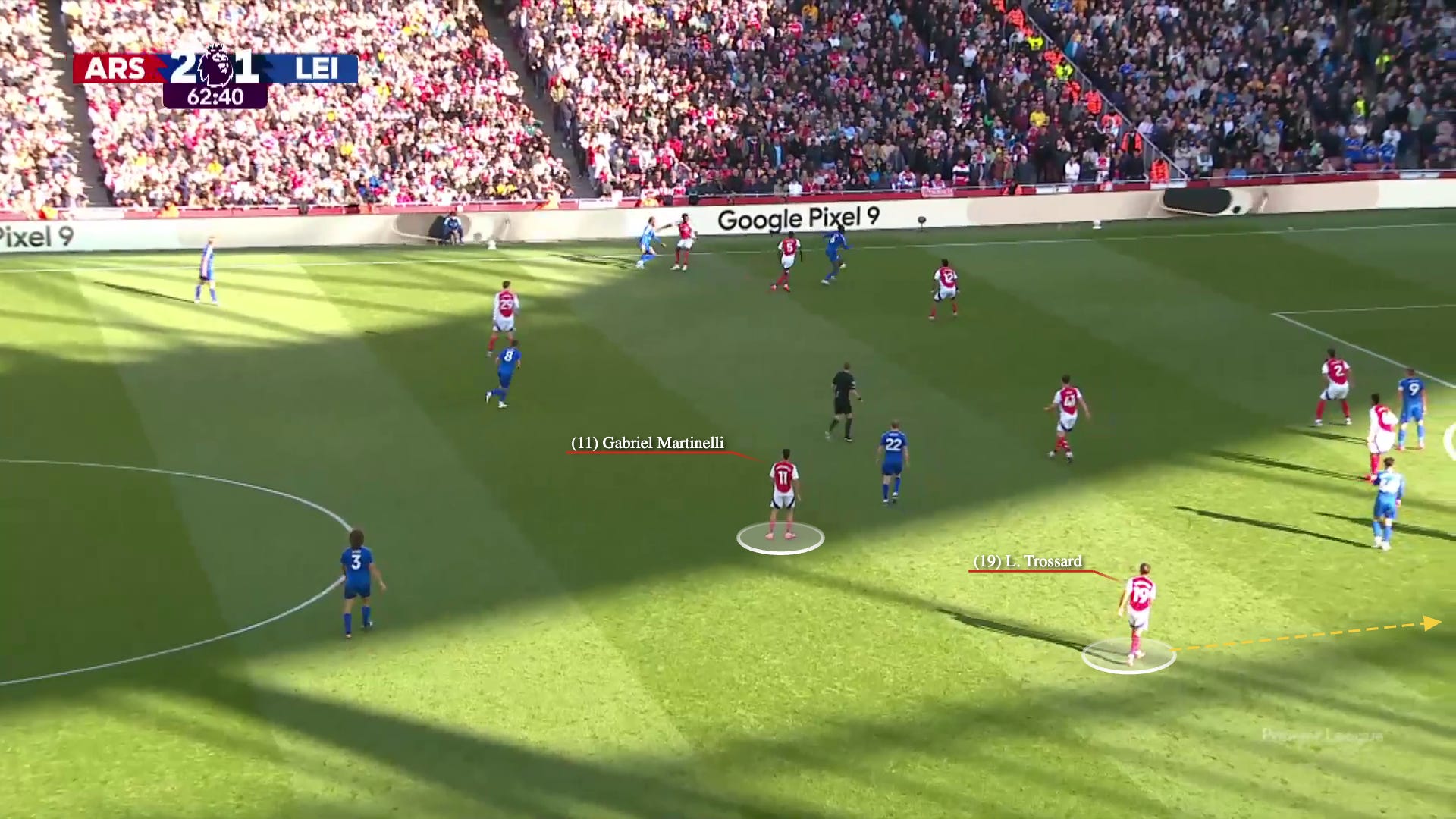

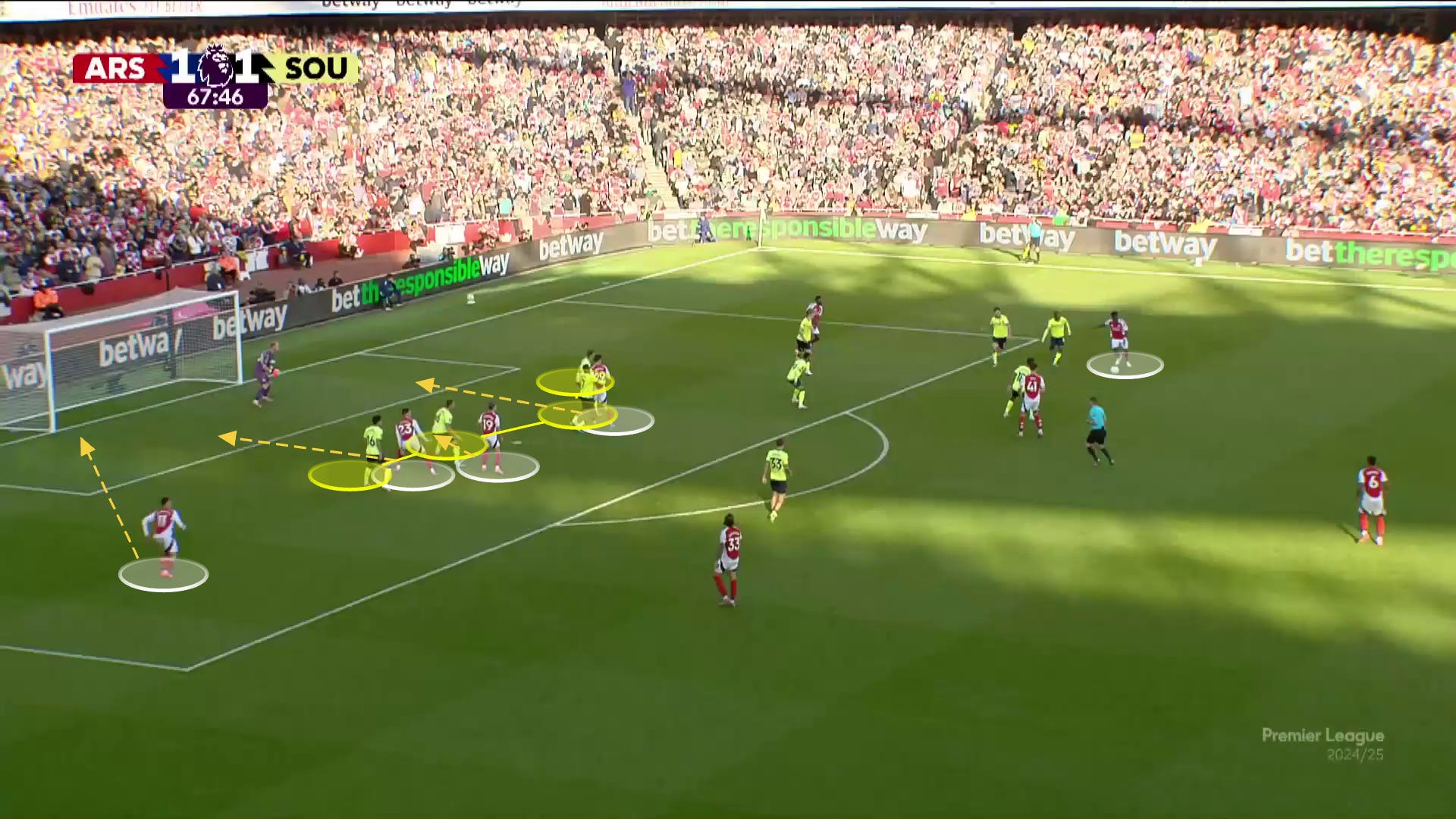

Next, we can see the rotation that led to the first goal. With Rice playing low, in a truer double-pivot setup, a ball loss is less costly. In previous games, Rice may be where Trossard is now. Instead, Calafiori starts to move his way inside.

From out of the screen, Havertz also drops, and this forms the all-fabled box midfield. There are just too many players for the PSG press to cope with, so they have to leave a man free. That man is Trossard, dropping to a position often held by the “left-back.”

Trossard is free to carry forward. He delivers the assist to Havertz that puts Arsenal ahead for good.

👉 Freeing up the CBs

Within these looks, we might be seeing something a little more: forward actions by the CBs.

Now, I don’t want to overstate things, as there has always been an element of this, and White is a real Total Footballer, and has always been astute at covering any momentary rotations.

But against PSG, there was a clear intention from Saliba to poke and prod the midfield, attract attention directly, create space for others, and then pass out of it. There were even times when he was a real midfielder, with Timber covering. I have proof:

Here, you’ll see more of what I believed to be a real tactical intention of the day. Saliba was intentionally trying to move around the thin PSG midfield as much as he could to drag and drop space at will. Timber covered.

There’s an aggressive lean here, but you’ll see he’s not the furthest man back — he is, essentially, a midfielder for a moment. (Yes, I do think he could play the “Stones Role” if it were ever necessary.) I don’t think these rotations should be quite so rare.

Gabriel, too, has enjoyed the additional freedom, but a more upfield variety. With a truer LCB than Zinchenko next to him, he can feel a little more freedom to push up and join overloads on the left side, as Calafiori shades back.

We’ve already seen plenty of that, with Gabriel pushing high, underlapping, and picking out some clever little passes. Despite lower possession, his high touches are up from 6.92/90 to 8.29/90. His overall distribution has been nice, too.

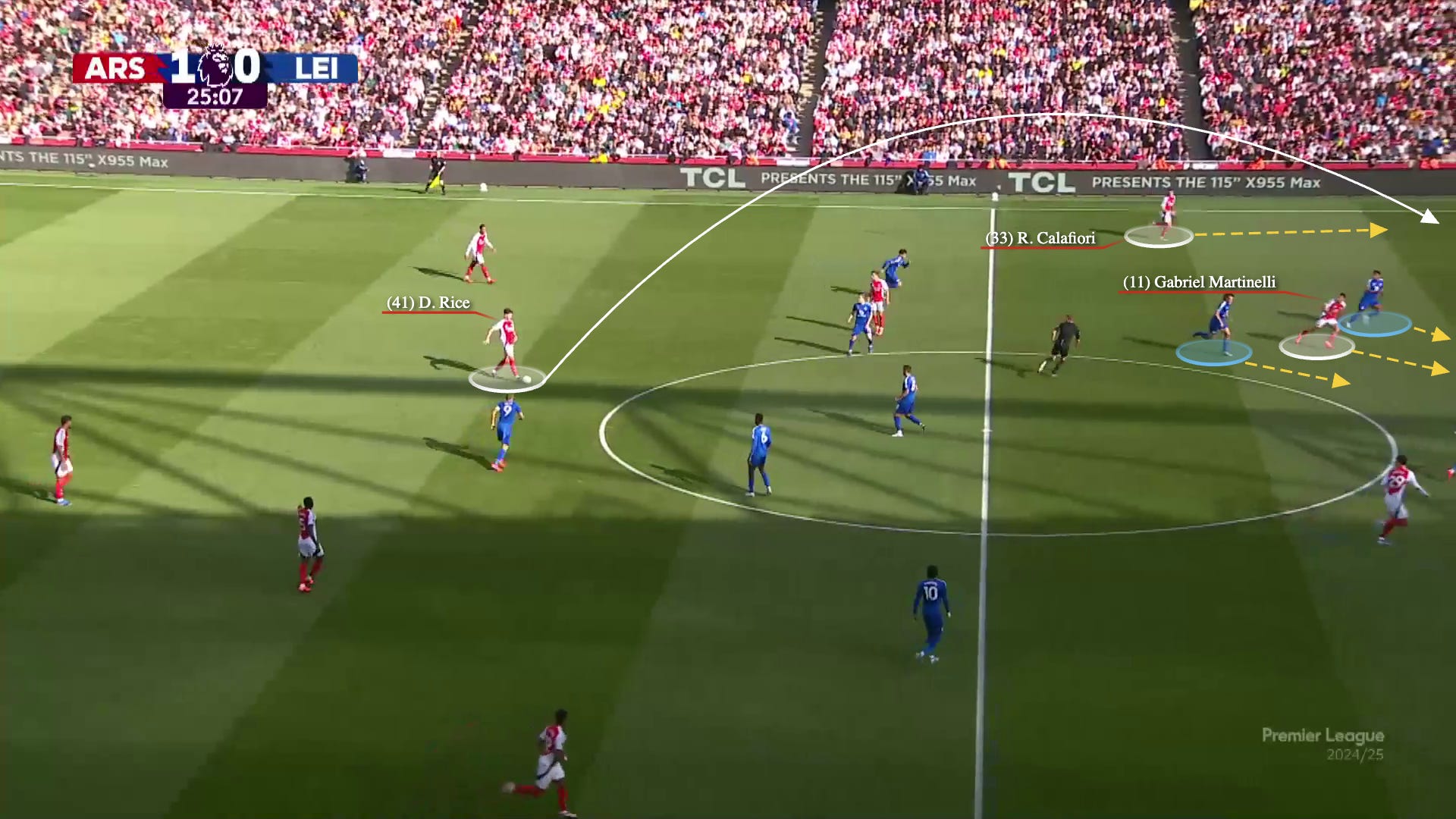

👉 Progression and jail-breaking

Here’s another place where there’s tangible improvement: credible threat as the widest player on the left. This is not really the happy place of Zinchenko, Kiwior, Tomiyasu, or Timber. While Rice is fine out there, it takes him too far from the middle of the action, and his right-footed crosses can take some time to get off.

Look at this left side!!!!

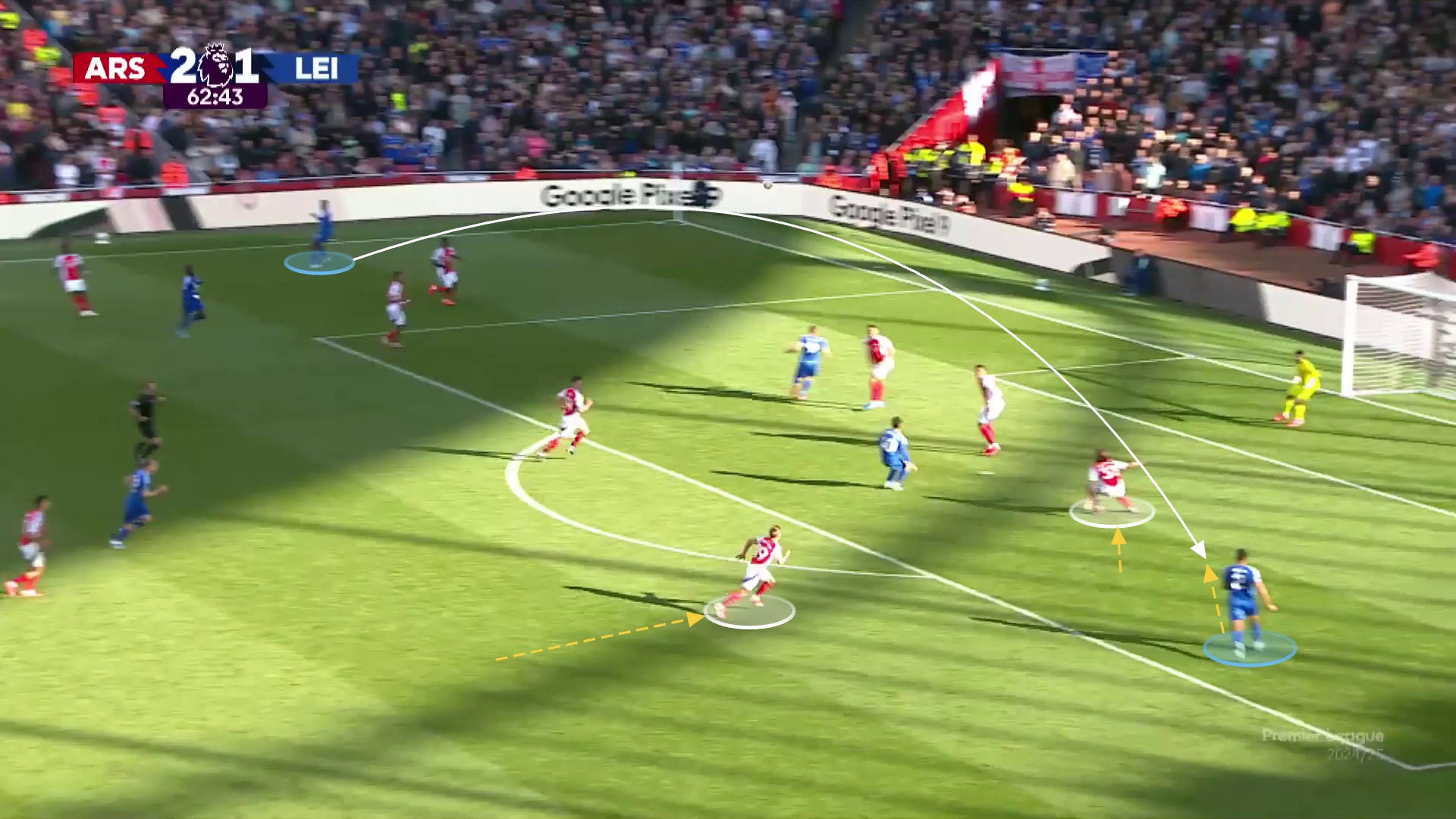

Below, you’ll see a timed switch, where there’s an interlocking run to pull runners inside, which gives the receiver space. As satisfying as these passes can be, Arteta does not like to switch unless there’s a specific advantage to gain.

From there, both Calafiori and Sterling offer something that the squad has generally lacked otherwise: quick, low crosses with the left foot.

Then there’s the upgrade I enjoy most. It seems whenever a free man is found in build-up, they lift their head, and a Wild Calafiori is galloping down the middle, ready to receive. He’s really fast and dynamic in these scenarios, which helps create better conditions for the attackers on the end of it.

On the right, there is just some slight modulation on White’s interpretation of this role. This underlap through the middle is definitely something we could see him do:

But there may just be a little more dribbling nous once Timber receives.

The difference, in sum? More aggressive and immediate carries.

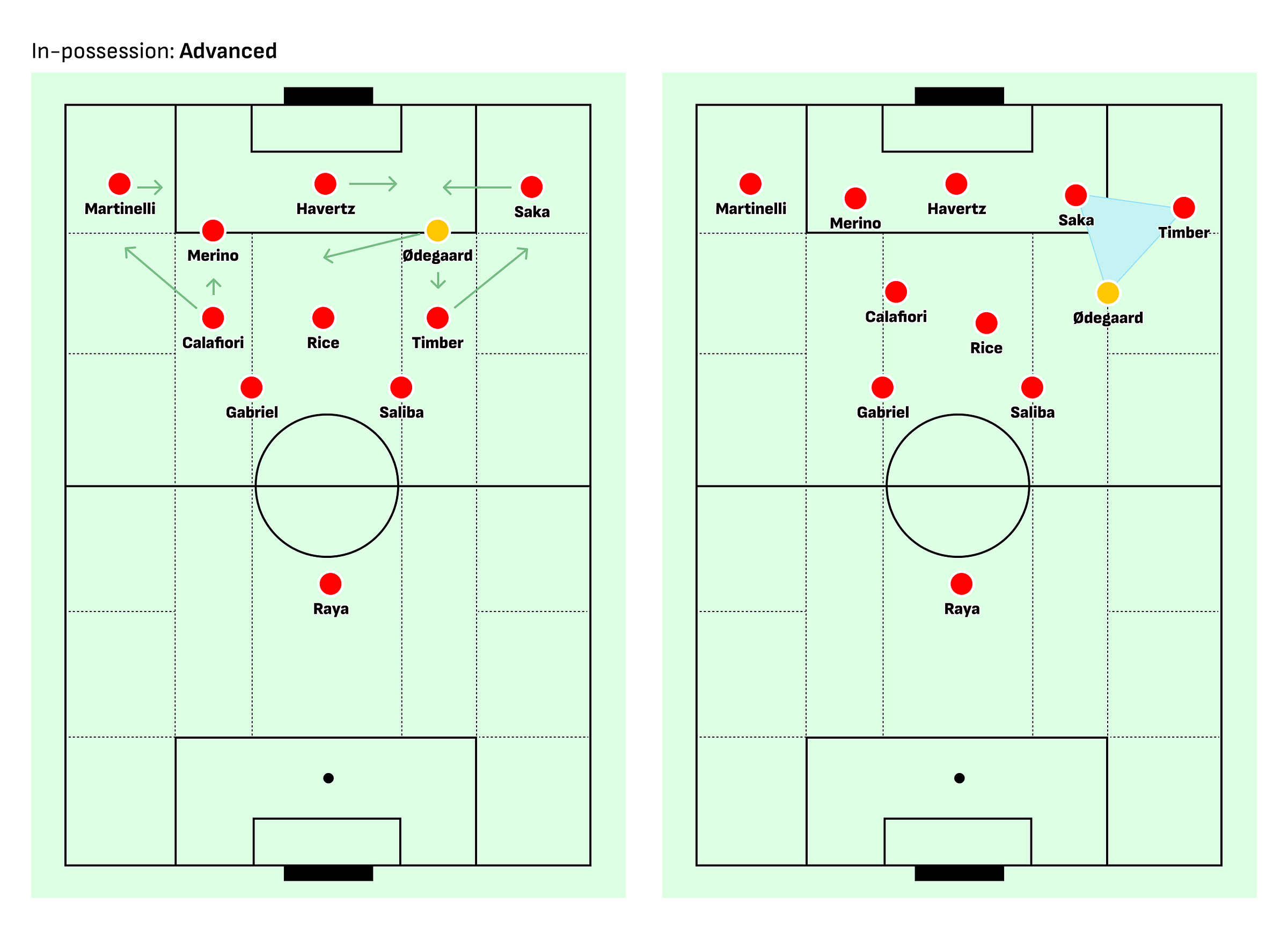

👉 Advanced areas

The biggest change, one hopes, is the work up top. With the expectation that Arsenal will continue to get a hearty helping of low-and-mid-blocks, this is probably the clearest opportunity for marginal gains.

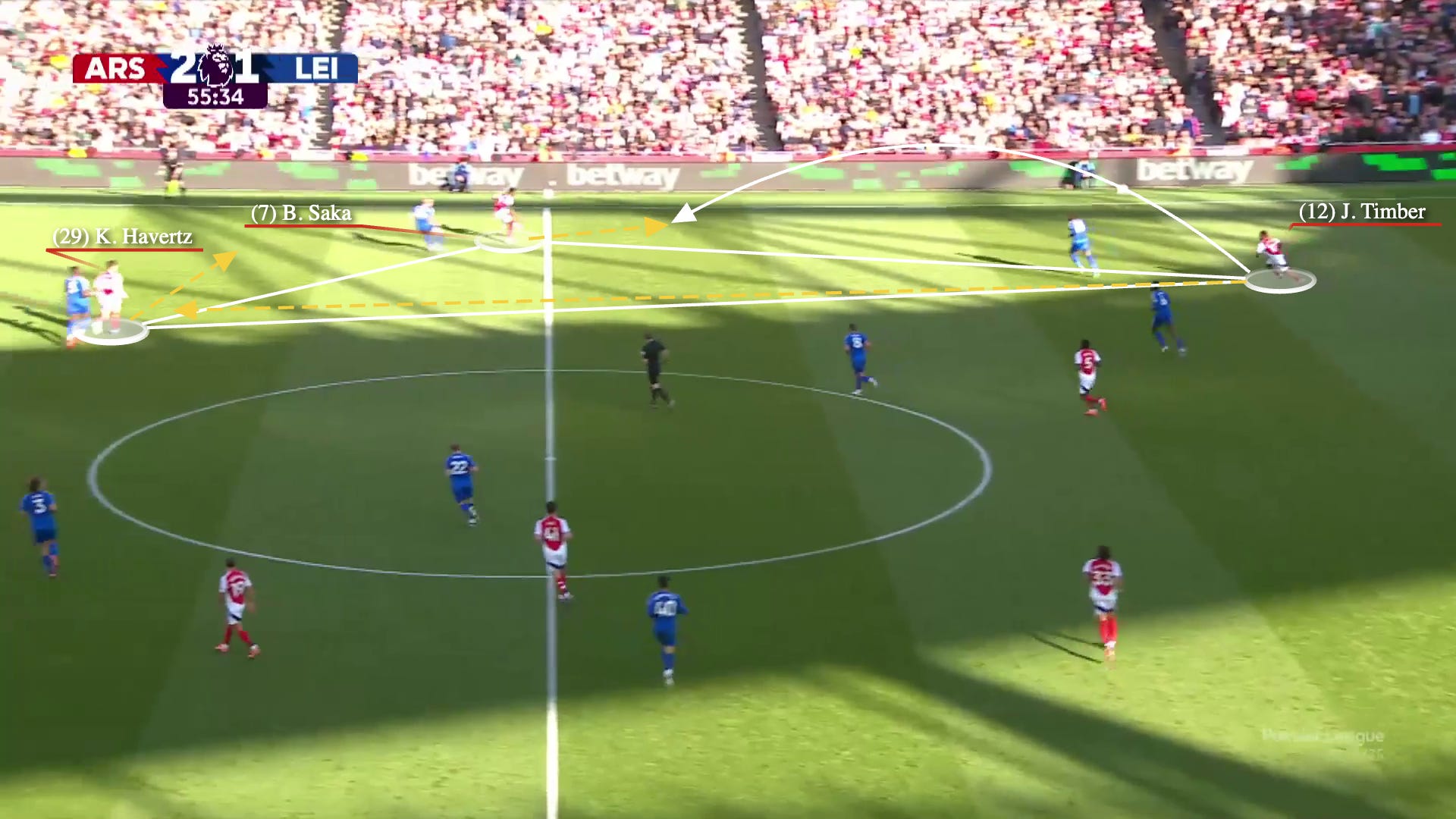

This has come through in numerous ways. The first is these underlapping runs. While White does these, too, this does seem to be a temperamental difference between White and Timber; White likes staying out wide, and Timber likes playing in the crowd.

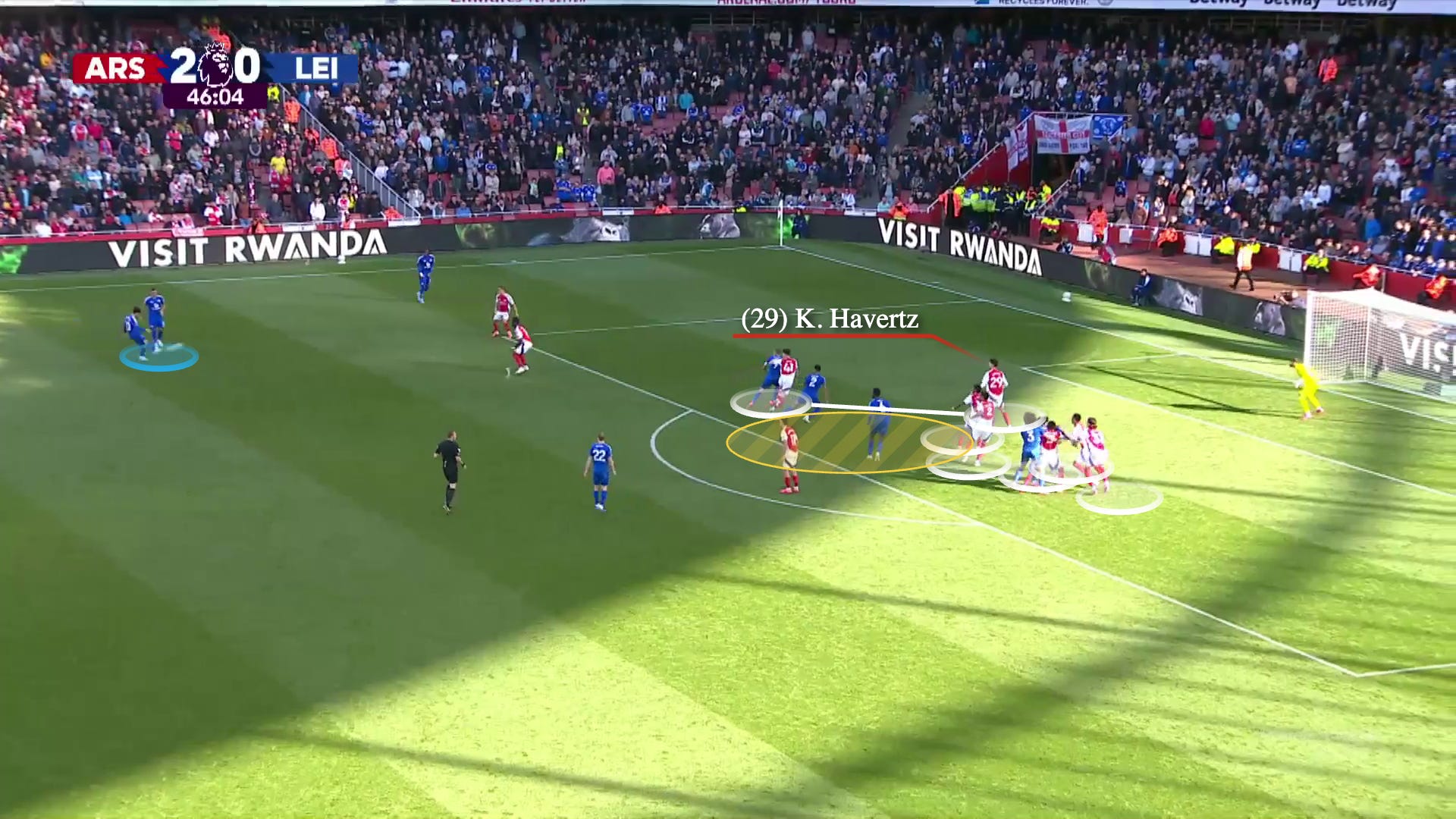

This led to a jam-packed setup that looked like this. Partey pumped a ball in, and Timber got a shot off.

On the left, Calafiori has been roaming in all three points of the triangle. Here, he hit Rice on an undercut.

In general, against lower-half teams, and especially when chasing a goal, their configuration allows Arsenal to throw a sixth player up into the frontline. With Saliba as a lone CB and Gabriel stepping up, it turns into a 1-3-6.

Calafiori’s wide carries are generally additive, as he can go both ways.

Here, he looks to exploit the defender’s expectation of a cutback.

This kind of bursting motion happened before the first goal. It may have been a penalty, I’m not sure.

That little pod had 62 total passes against Leicester.

Against Wolves, for instance, Zinchenko/Rice/Martinell combined for 27.

This balance adds to more thrust through the middle.

On the other side, there seems to be a little bit more running and dribbling, as well. This little cut almost felt Saka-like, setting up a bouncing opportunity for Havertz.

Of course, he had the assist on the overlap. Perhaps a little loose, but it counts all the same. That’s the inside soft spot we’ve been asking Martinelli to crash as much as possible:

👉 Defending (specifically, 1v1)

There weren’t major concerns about Timber and Calafiori’s adjustment to the in-possession game. It’s more of a question of the scale of impact. Out-of-possession, though, there was a wider range of outcomes.

Despite how committed, athletic, and duelly he is, there was a lingering concern or two on the Timber front this year. For one, he was overburdened and lost a few runners in his final year at Ajax, and is adapting to a new position here. For another, he’s coming off a knee injury.

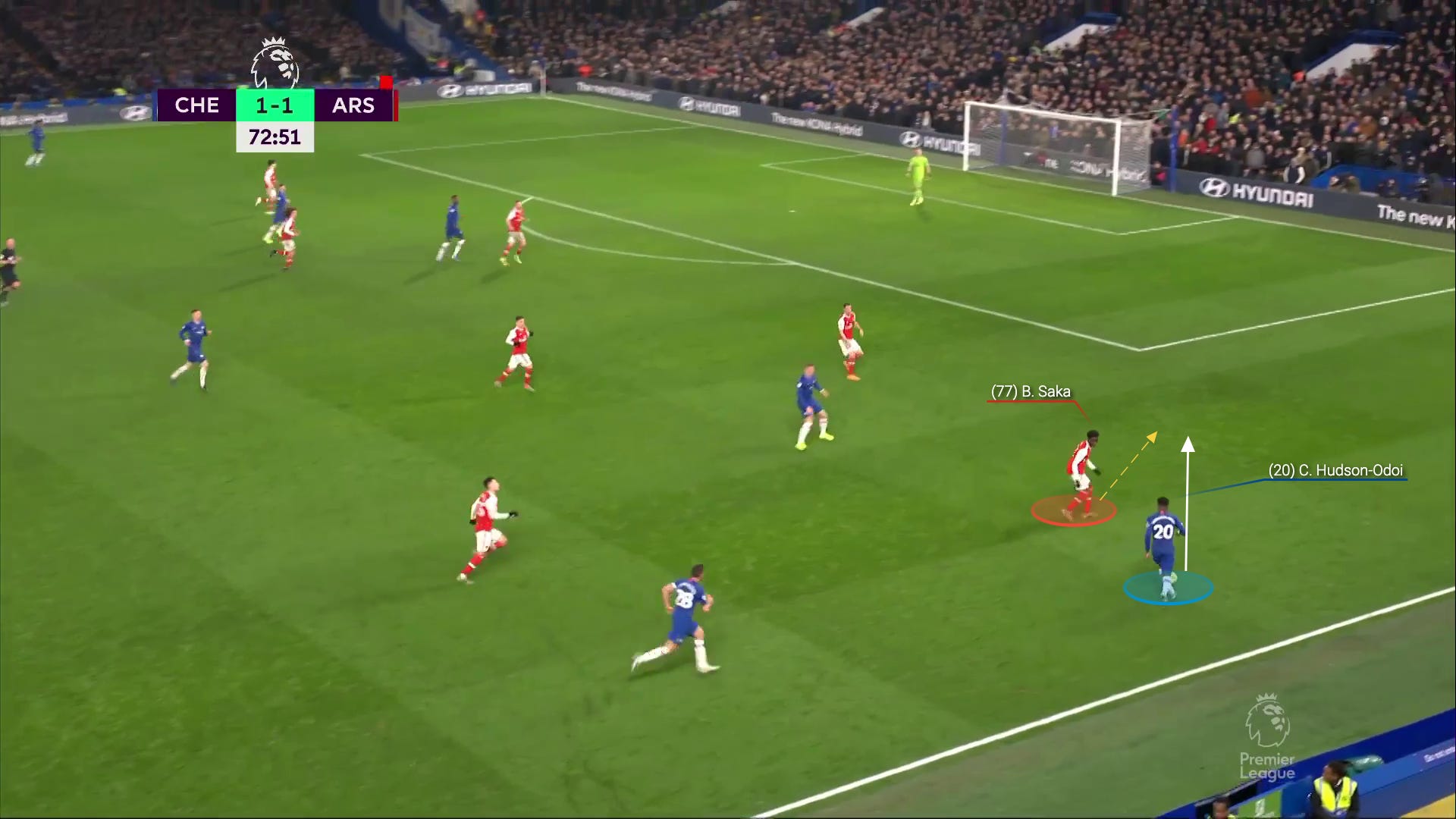

None of that has come to fruition. He’s looked like Arsenal’s best wide 1v1 defender, and may even be helping Saka devote more energy to attack in the last two games:

"He gave me a lot of confidence that when he's one vs. one with an attacker he's going to win the ball back and give it to me," Saka explains. "On the ball he's so composed, so calm and confident. He's a top player, I'm happy he's showing it. It must have been hard for him, knowing that he had that much ability but was on the sidelines for a year. He always kept his head, stayed humble and worked so hard. I'm happy that now he's getting the praises he deserves."

Barcola and Doku are two of the toughest assignments in the world. I don’t doubt that there’s a tricky moment or two in Timber’s future, but so far, he’s been pretty much impervious.

He’s a bit like Saliba in that he’s so immediate and functional in his actions that they often look easier than they are. This kind of lean and poke is no walk in the park, but Timber makes it look like it is. He’s already got so many of these on tape.

The other side is more of an open discussion.

Calafiori has looked elite at open-play aerial duels, often setting off attacks with his dome. Both full-backs have been excellent on the counter-press — some of the best you’ll see.

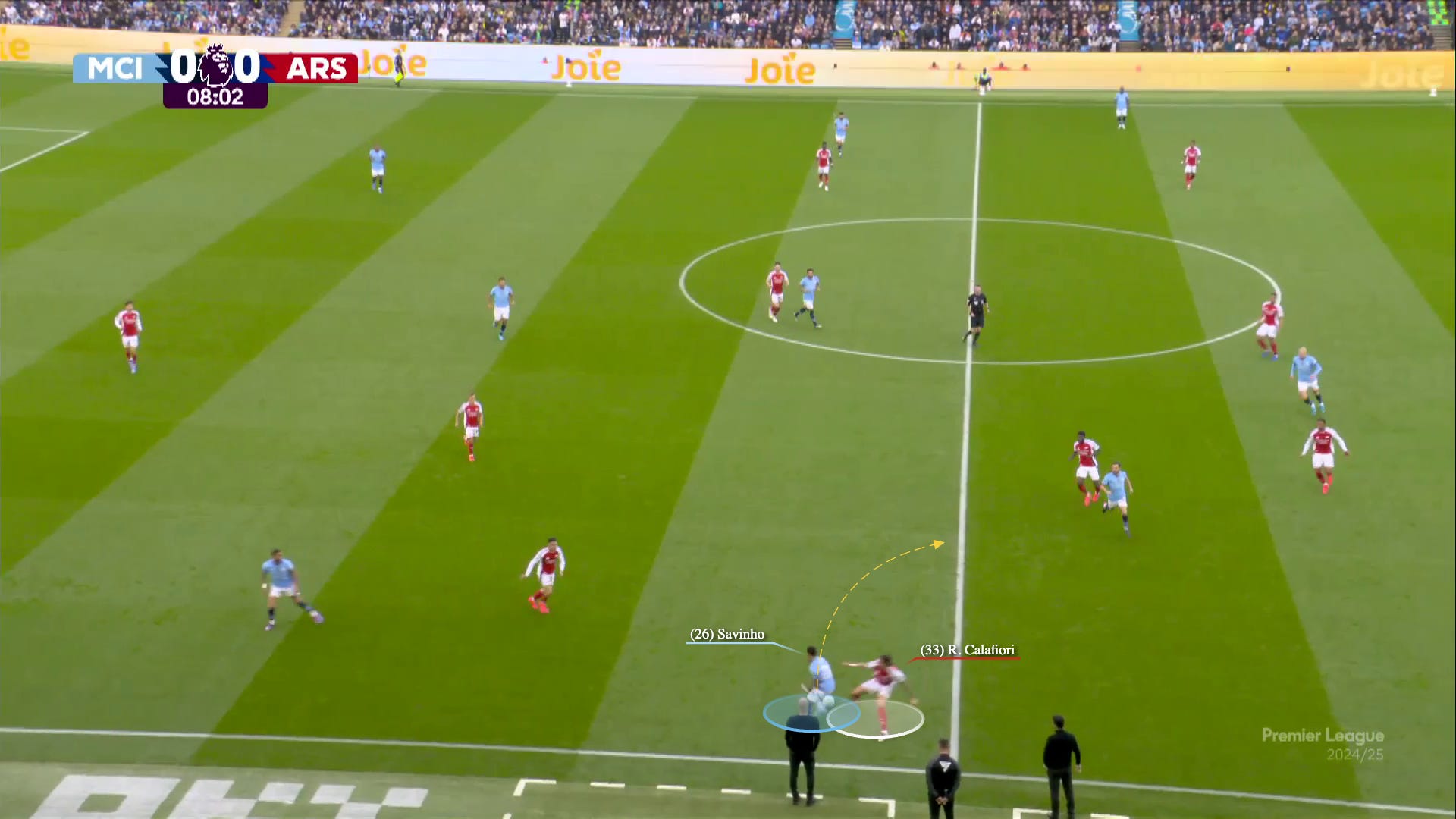

In a pure 1v1 sense, Calafiori’s had some statistical success, too, winning 7/11 of his defensive duels (63.6%). But he’s also had a few memorable struggles. At various times, the likes of Savinho, Hakimi, and Dibling have gotten the better of him.

From my scouting report, written before he signed:

Calafiori has many of the hallmarks of an Arsenal success: he’s tough, young, physical, flexible, multi-positional, engaged in the duel, tactically aware, and crisp in lower build-up. He has a makeup that is genuinely hard to replicate: he gets compared to Stones a lot, but that feels insufficient to me. There is something uniquely expressive and rambunctious about Calafiori.

[…]

Whenever he gets the option to engage, he will take it. His “controlled-aggression” can sometimes make way to “aggression-aggression.” This can lead to moments when he unsuccessfully presses in his own third. He’ll jump out at a player based on an initial read. Then, when something unexpected happens (a deflection or great pass), Calafiori can get caught in no man’s land, and sometimes swing to try and bring them down.

Out wide, he usually has a fundamentally sound initial 1v1 style from his time spent as a proper full-back. He’s limber enough to get low, he gets on the balls of his feet, makes small steps, and sends the attacker the right way. But his impatience often wins the day.

Like White, I carry a few near-term worries about his ability to keep up with quick changes of direction from the world’s fastest wingers. They are just on a different level in terms of high-end pace and hip-wiggling agility, and like to exploit lungers (as top dribblers are often reactive, not proactive). Players with his level of speed can, and often do, turn into elites. He has the tools to become special, but I could see him lunging into air a few times along the way.

I’ve shared clips like this before.

He goes to close out, his angles are too aggressive and “outward” facing (see how much he shades right and leaves the byline open to Hakimi’s preferred foot), but then he compensates and figures something out anyway.

If you watch the below clip a few times, you’ll get a sense of his psyche as a defender. There’s a sensible route where he just blocks the lane and squeezes. Instead, he makes a sharp dart right and tries to blow up the spot.

But he’s also been simply blown past two or three times now.

We covered the early Savinho stuff last time.

He later settled down and started prevailing in his battles.

What do we make of all this?

It’s a little complicated. For one, Hakimi has registered the highest top speed of any player in the Champions League this year (36.5 km/h), faster than Mbappé or Davies or Adeyemi or whomever you may be thinking of. For another, Calafiori may have been feeling the effects of a knock on his calf. He’s apprised himself well in the majority of his duels.

But speed is still a thing. Tyler Dibling may have a lot of talent and pace, but you’d still prefer a situation in which the 18-year-old wasn’t able to dribble directly around your full-back.

For Calafiori, it all comes down to a) timing and b) the aggressiveness of his angles. It’s a tricky balance. His impulse is to close the distance as quickly as possible. That logic is sound: by disrupting the reception, he decreases the chance that he is turned on pace. That aggressiveness is also in his DNA, and is an essential part of his character on the pitch. But his angles are often too aggressive, which can leave him defending air.

If you watch Saliba, you’ll notice how much pragmatism he employs. He blows up the reception if he can get there. He often drops and gets high ground if he can’t.

Moving forward, Calafiori will have to ease up his angles at times, and then learn the subtleties of when he can go and when he can’t. It’s not a deal-breaker, and there’s a good chance he turns into a real stopper out there; as we've covered, people with his level of speed often have. But it’s something worth watching.

👉 Set pieces

An important part of a set play is a cumulative big-guy advantage. If you line up against the other squad in the #tunnel, arrange yourselves tallest-to-shortest, and your fifth-tallest is a lot bigger than theirs, you’ll usually find a matchup to exploit.

From the Calafiori piece:

He also represents an improvement on the team from an aerial and set play perspective, as he’d sponge up minutes previously held by Zinchenko and Kiwior. The sickos get more ill.

While Timber has been scrappy, he hasn’t looked like a great aerial performer. Calafiori, though, has definitely added to the advantage. Here’s both of them getting in on the action.

Calafiori had three headed shots on target against Leicester.

While we’re on the topic: in the first half of the PSG match, we saw one of the more complex set play routines we’ve seen to date. Trossard talks to the ref to mix in, Martinelli was on one knee, and four Arsenal players lined up offside. By messing with the timing of the kick, they mess with the cleanliness of the PSG offside trap.

If Trossard gets to the end of this ball, it doesn’t matter if his colleagues were ever onside, as he was. If this hits, Trossard has four options for a cutback cross.

👉 Full-backs: the final estimation

Let’s not get too far ahead of ourselves. Take it away, Simple Minds:

Don't you, forget about me

Don't, don't, don't, don't

Don't you, forget about me

The new objects are quite shiny.

But Benjamin White is still quite good.

Here, I’ll prove it:

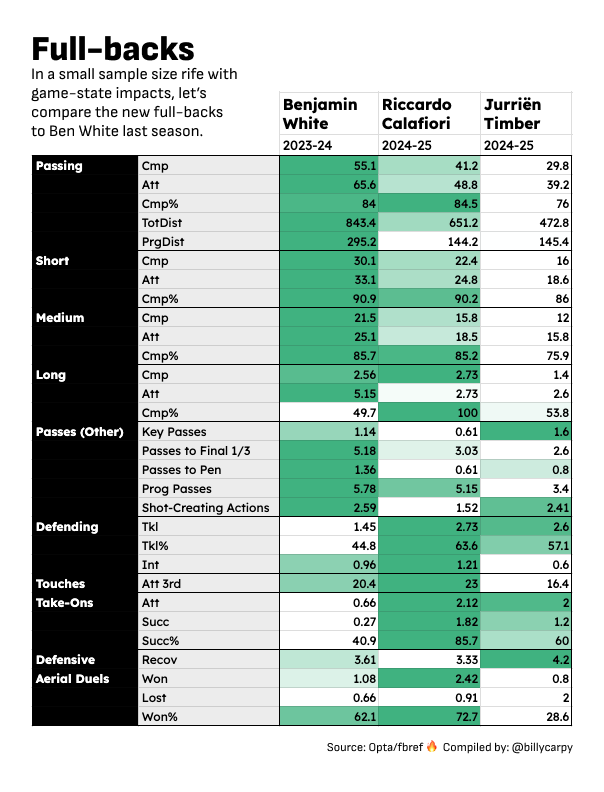

Timber and Calafiori’s progressive statistics are likely to tick up. Timber played a more secondary, “in the pocket” role as a LB, and there have been huge game-state effects in this small sample size for both. But White is still a high bar to clear.

I’ll leave with some scattered thoughts:

Timber and Calafiori are special brains and talents. They have the potential to significantly alter Arsenal’s dynamics. We’ll see this in counter-pressing, Timber’s 1v1 skills, set plays, increased velocity of attack, and more fluidity up front.

Some of this season’s peak rests on a question. If the Calafiori/Rice pivot, with Timber/Merino/Ødegaard dropping to help, can prove sufficiently dynamic, then Arsenal can have a threatening attacking force while being almost unquestionably best-in-the-world when out-of-possession. It’s not a settled question; there’s a decent chance of progression stalling as the team misses the line-cutting of the likes of Partey, Jorginho, and Zinchenko. But if it works, it’s off to the races.

These roles are extraordinarily demanding. You’re expected to run overlaps, underlaps, carries, counterpresses, play like a controlling midfielder, and then take personal responsibility for 1v1s against Premier League wingers. However injury-prone our full-backs may be, I think there’s some chicken-and-egg there: with so much running, so many duels, so much action on both ends of the pitch, it’s easy to see how players pick up knocks. I’m honestly concerned about it, and wonder if it’d be pragmatic to rotate in some games of full-backing normalcy, especially for Calafiori.

As such, though, we should fully expect all three of these players to play a lot. We don’t have to pick only two.

I don’t think this is all shiny toy syndrome. If all three are healthy, I strongly lean to Calafiori at LB, and marginally lean to Timber at RB. It’s early days, and those connections will continue to build and improve. If things go according to plan, this should be the worst we’ll see of them. Not bad, eh?

Said Calafiori:

“It’s going very well at Arsenal. And in six months, it will be even better, you’ll see,” Calafiori said. “My life has changed being at Arsenal, I can feel the responsibility. And I like it, I love when people expect many things from me.”

🛑 Merino, Calafiori, and the defensive shape

Calafiori has offered another unlock: he’s helped Rice stay lower by default, which decreases the distance between him and Partey/Jorginho, improving the team’s transitional defending. He is the best player in the world at this, and has often found himself too far from the action.

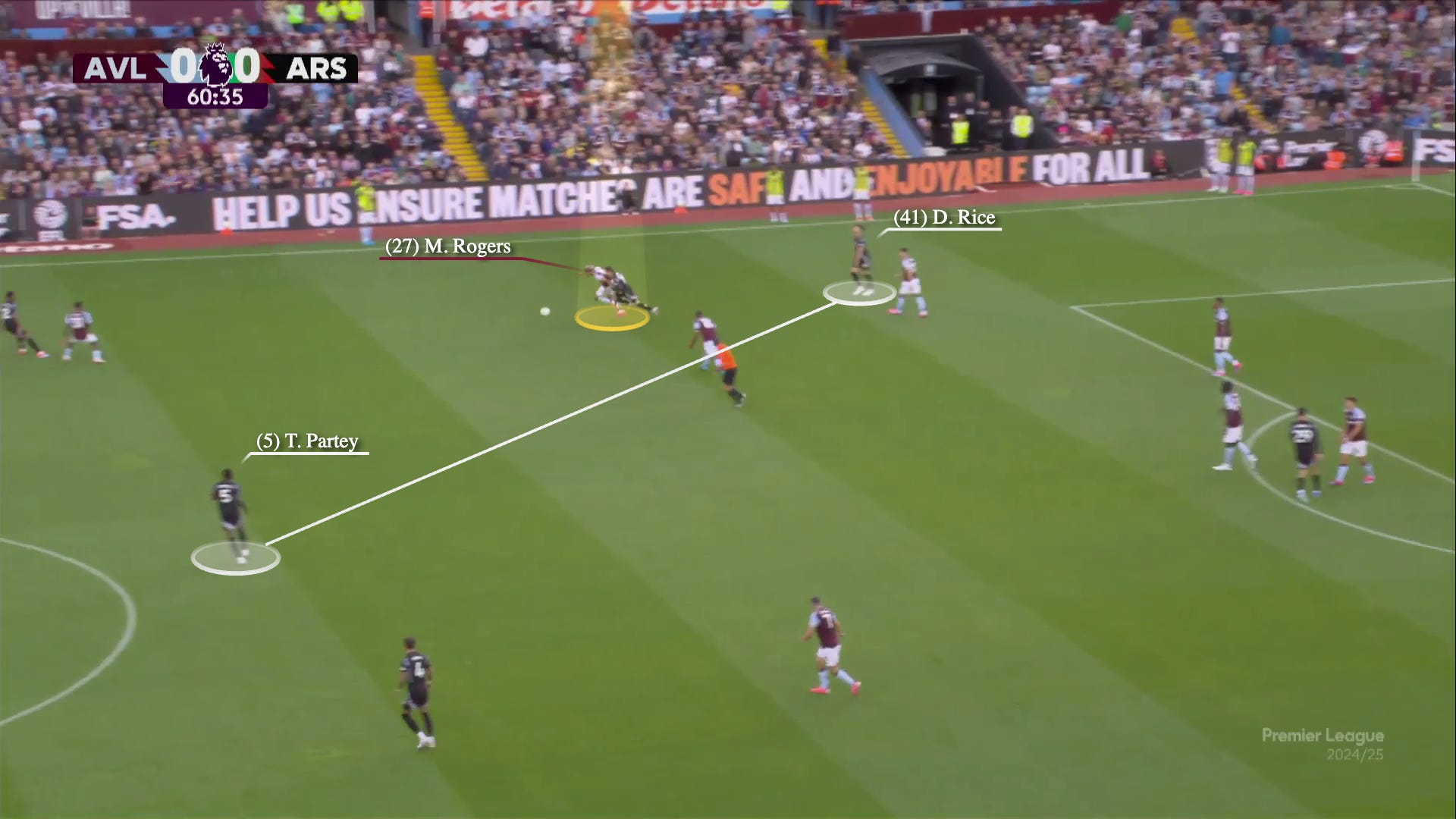

Some of the early season vulnerability was because of this distance on a ball loss. Morgan Rogers Island is not a good place to spend your holiday:

While Rice still pushes high a lot from the LCM, Calafiori is also likely to take up those zones. That means that if Sterling lost it on this dribble, for example, Rice is right by Jorginho, and is supported by three behind. His responsibility is to eventally fall back centrally instead of the wing, which helps as well. It’s more of a cage.

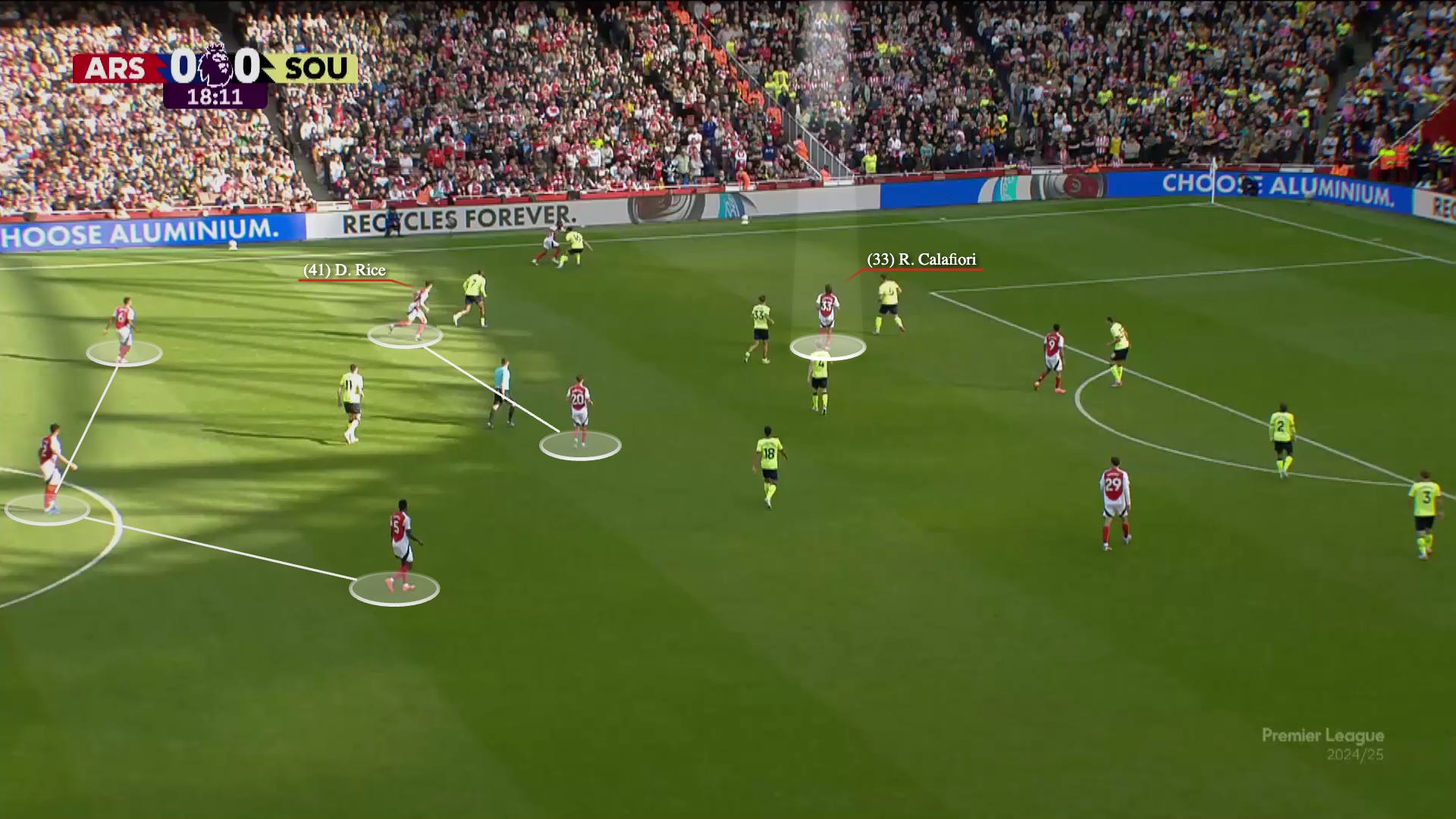

The press has generally been effective, and was especially deadly against a somewhat naive Southampton approach. Despite his limitations, Jorginho is always where he should be, points out every movement by the opponent, and is willing to back up every press jump, even if it leads him to a risky situation personally.

Our Starman created another goal from nothing. It was pivotal to the flow of the game.

But despite the 10-man heroics, the defensive shape hasn’t been able to consistently show its most devastating final form, he says greedily.

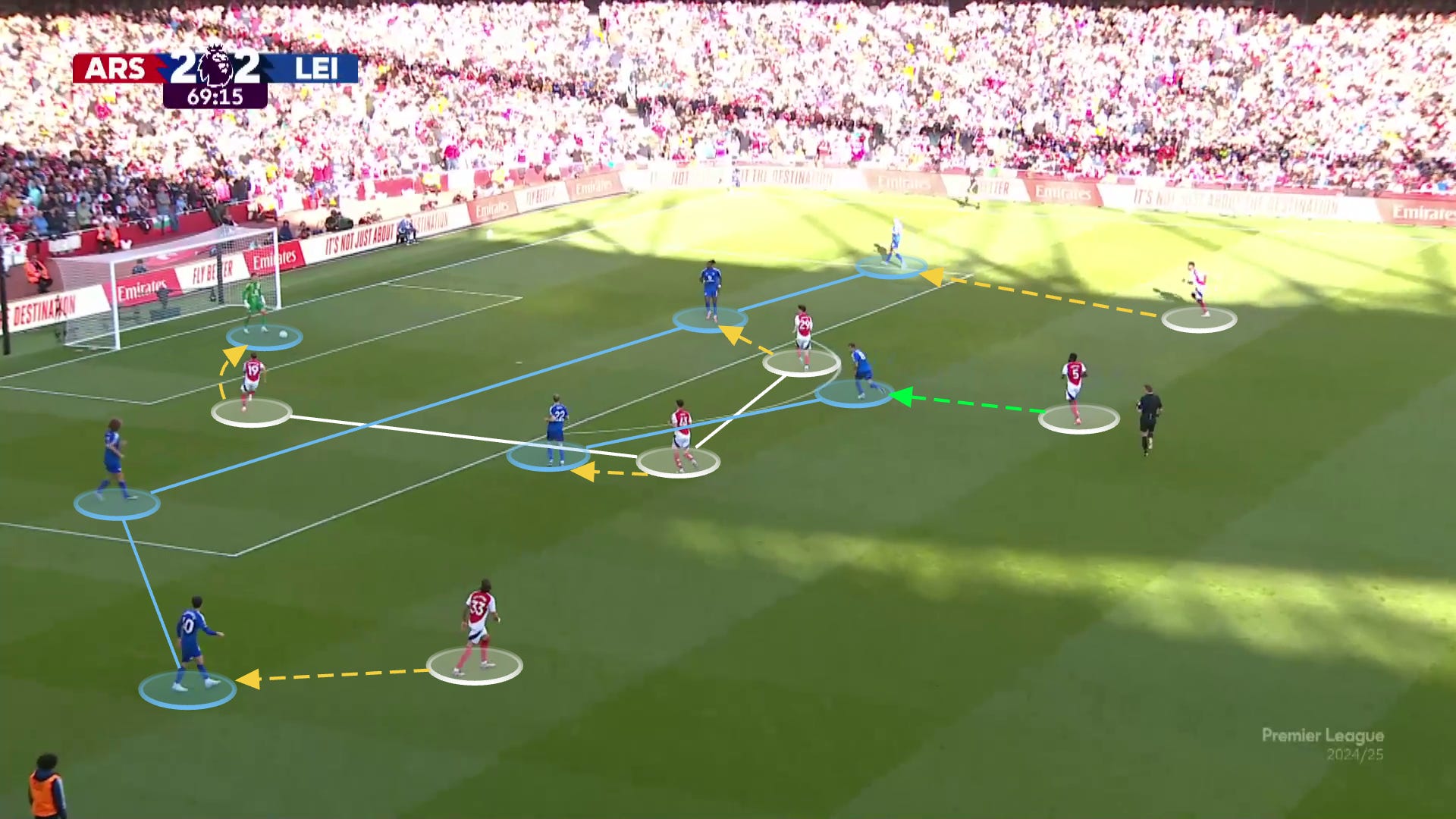

The first Leicester goal happened because of a truly odd Havertz mistake, leaving a discombobulated line and a huge space open through the middle.

On the other end, when the press is working, it looks like this.

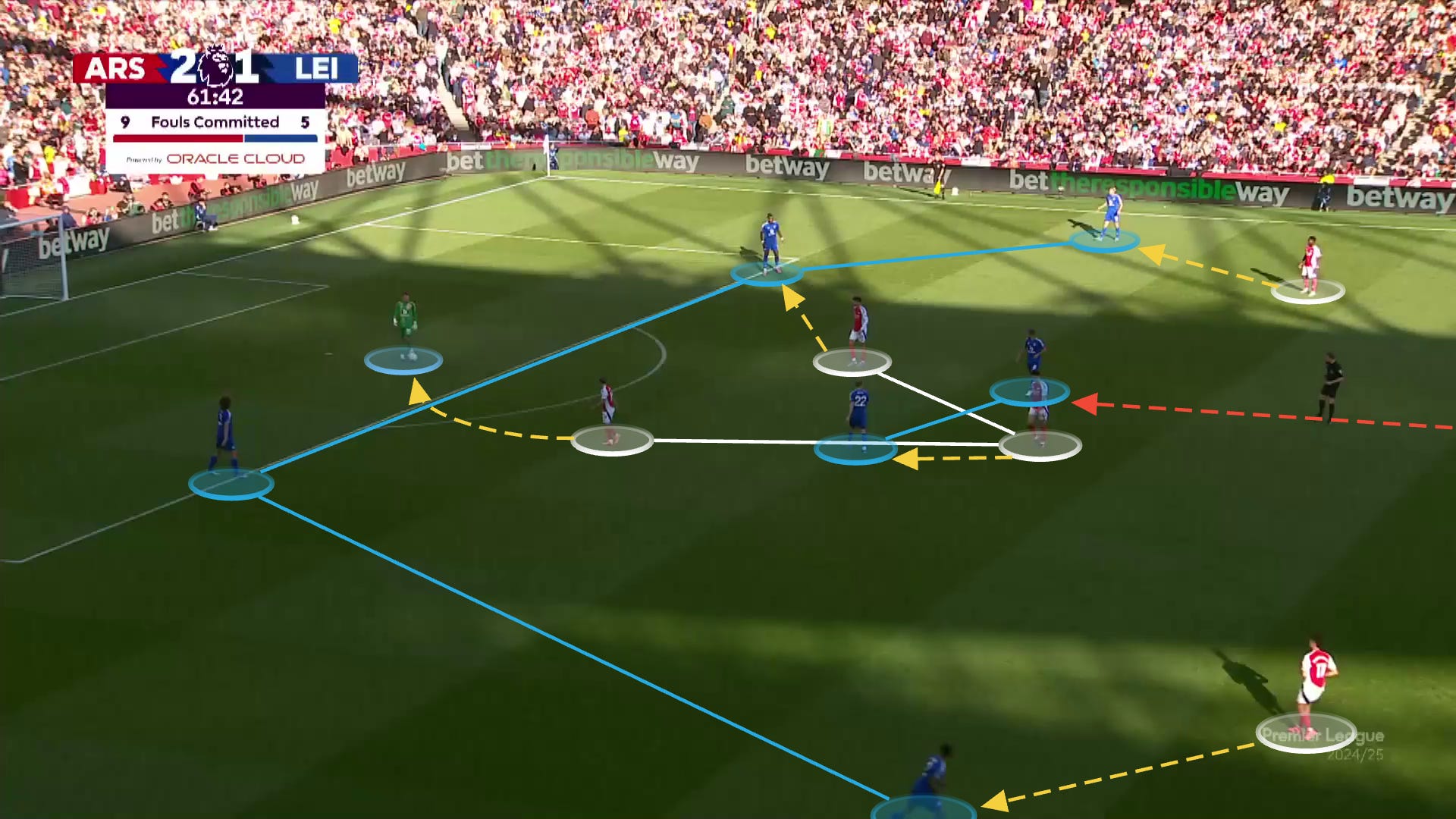

Full commitment, clear responsibilities, no man left free. When Partey trusts his legs to arrive, he’s been effective at stripping the ball, with six advanced tackles to his name (sharing the Premier League lead with Carlos Baleba).

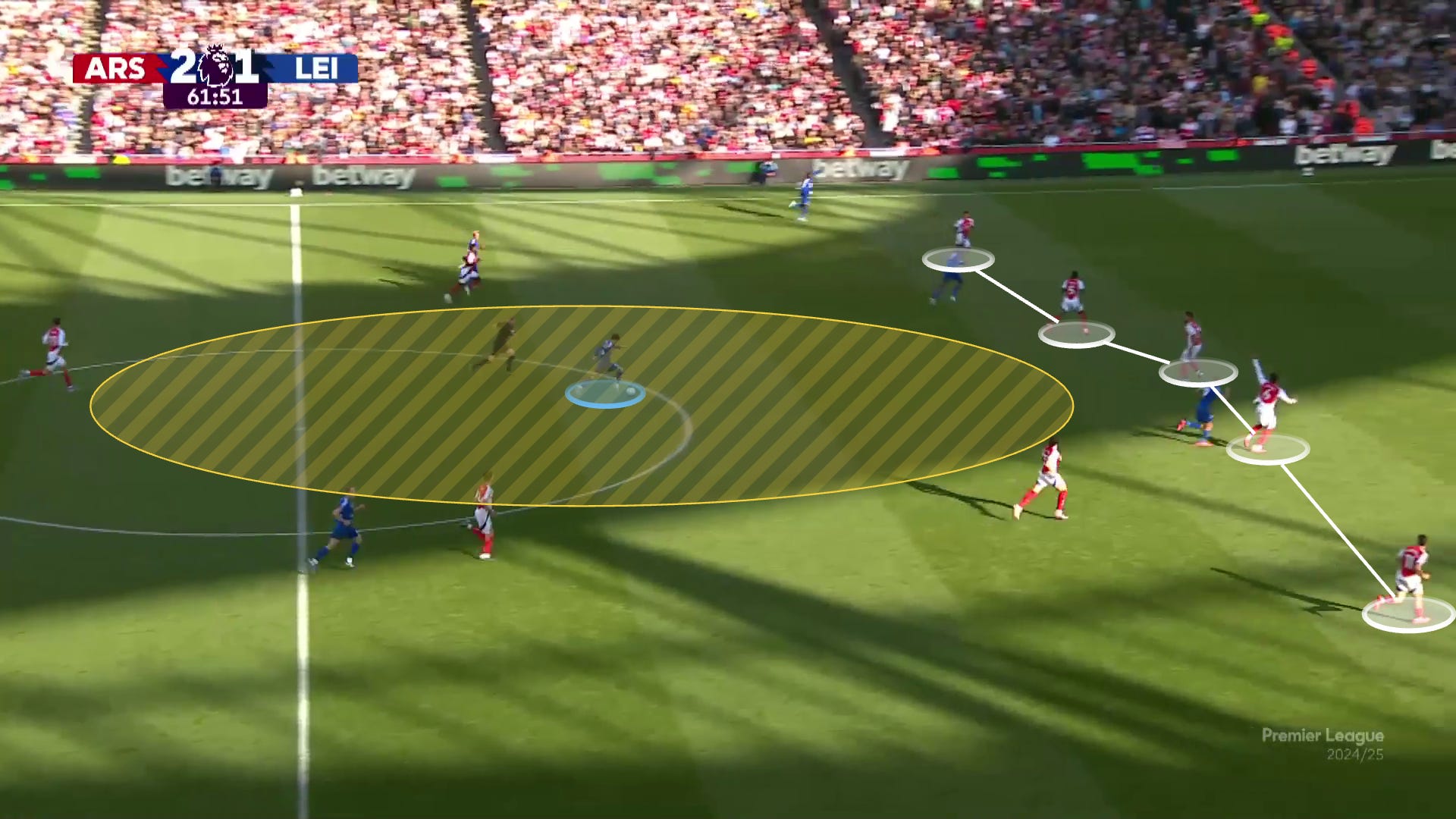

But there continue to be moments like this, particularly as the game wears on. The front press only works with sufficient backup, and if Partey doesn’t have it in him to get there, he dissolves into the backline, resulting in a free man for the opponent.

That free man simply glides into a cavern of space, and the middle of the pitch opens wide open.

With nobody interrupting the carrier, the result is Billy Yelling, and a shot on goal.

This was indicative of a period of lost control in which Leicester eventually drew even, and shows how phases of the game are never separate: better pressing means more possession.

That second goal was partially the result of a Martinelli/Trossard switch in the block. After switching, Trossard was caught a little upfield, and had to run to get back to the play.

Calafiori got sucked in, and Trossard didn’t make it all the way back. Justin scored on the volley.

Arsenal gained control again with more consistent application of upfield pressure.

That’s the ticket.

Not to oversimplify, but the solution to any of these defensive questions is essentially: Mikel Merino.

As we saw late against PSG, all six of these players are a top-five presser in the world at their position, potentially even higher than that. Behind them is four centre-halves:

Merino immediately let his presence be known with a series of characteristic strips.

…and wonderfully, we’ve seen some of the first Martinelli releases into space. This felt offside but wasn’t called. Yes, the dynamics around Martinelli look greatly improved.

I’m also excited to see such balls for Havertz and Sterling.

There will be a mutual adjustment period here, too. Merino is hilariously active as a dueller, as you’ve no doubt already read (and seen). Rice is actually more measured.

For Merino, this leads to bouncing balls in the middle that require the team to unfurl in unison and for outlet passes to be hit immediately, in Kloppian fashion. While we now have our outlets, the immediate transitions don’t always look reliably crisp, and the ball is often lost right back. There will be a little bit more chaos in the middle. Hopefully, the happy kind.

Once Merino came on, the defensive shape looked so tough, but the possession numbers were low.

Much digital ink has been spilled about Merino’s supposedly underwhelming numbers as a passer, but I’m generally looking forward to what he brings there. My more pressing area of concern (or at least curiosity) is the below. If he doesn’t get the ball off quickly, he can carry himself into trouble, and lack some of the on-ball agility to get out of it.

We saw how his aerial presence helped usher in the decisive goal against Southampton. He pulled the defenders in, counted, nudged Martinelli to get closer, and Saka did Saka things.

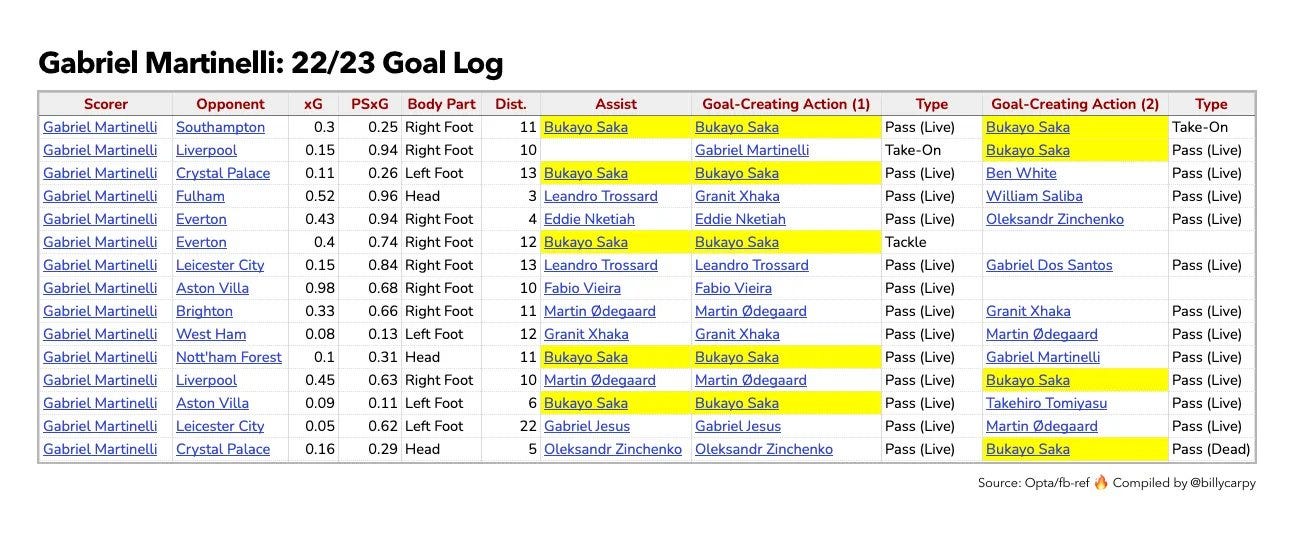

Last year, I wrote a long thread about how direct hits from Saka — as much as anything else — were the key to unlocking Martinelli’s goal contributions. Lookee here:

This has the makings of the best second-ball team in the world. At a time when Manchester City is looking decidedly underathletic, this is good timing.

I’m anxious for Merino to become a starter.

🔑 Saka, Havertz, and the cømeback

The attack looked incredible against Leicester, as the team has transitioned more into a swirling 4-4-2, with Trossard and Havertz up top.

As a reminder of how ugly it got:

The star of the match, the season, and the world, has been Bukayo Saka. Shouldering more responsibility, any sane planet would have him as the frontrunner for Premier League Player of the Season. He may be the best player in the world on form.

A few stats:

He’s raised his key passes from 2.81 to 4.29 per 90

He’s raised his shots from 3.15 to 3.97 per 90

He leads the league in shot creation (8.11/90) and is second in goal creation (1.75/90), only behind Sancho (!) in a small sample size

He’s doing so on 8 fewer touches per 90, as Arsenal have less possession

His goals have fallen, but he’s 4x’d his assist rate

He is, essentially, shouldering the creative load of two players, and performing brilliantly.

Last summer, I wrote about how Saka’s formative experiences as a left-back helped turn him into one of the primary antagonists of that position.

Here were five of Saka’s skills that identified as perhaps being extra-refined thanks to his experiences further back:

Avoiding (or counteracting) the moments of maximum defensive leverage when receiving the ball

Giving the defender the smallest, lowest, most balanced target to try and push against

Pre-empting a defender’s leans and hand-checks with leans and hand-checks of his own

Showing “neutral intentions” when dribbling, until the defender shows imbalance

Fighting for position (instead of the ball itself) on long touches or loose balls by using his “body as a barrier”

And that’s what we’ve seen since.

Prior to the last pivotal period of the season, there were a few open topics:

How Havertz would fare playing the “Ødegaard role”

How comfortable Nwaneri would look in his first high-pressure minutes

How dynamic/interesting Timber would look at RB

How the team would fare when White was defending injured

How the team would cope without its creative capitano

The answer to everything has been: Saka, Saka, Saka, Saka, Saka.

The primary beneficiary of this, to my eyes, has been Havertz. As we’ve covered when we’ve discussed the Bu-kai-yo connection, they seem to be on the same wavelength, and every attack seems to stem back to one of them. The third Southampton goal was the result of a messy, dogged moment from each of them:

This play, in the waning minutes of a cooked game, demonstrates who ultimately succeeds in the Premier League and why.

…and I must include this one, too. 🥰

Arsenal have been able to manage in Ødegaard’s absence, and it’s true that Saka has been as productive as ever. What does this mean for Ødegaard’s return?

There are a few things to remember through this period:

In the three matches that Ødegaard played this season, Saka had 4 G+A (should have had 5, except for a slight deflection), and logged 16 shot-creating actions, all including a healthy portion of that being played with 10 men. Saka’s usage was high, lower-touch, more goal-hungry, and slightly closer to goal in that period. He was, uh, plenty productive. To my eye, his usage was near-ideal.

We haven’t effectively been able to keep up possessional dominance when it’s hard. We’ve lacked the player who can put their sole on the ball, slow things down as needed, and dictate play. We’re going long too often. I really felt this against Atalanta in particular, and there was also some weaving and final balls that would have been nice in the first half against Southampton.

Arsenal were below 1.0 xG against Spurs, Atalanta, Manchester City (understandably), and PSG.

Ødegaard jogs back into the XI at his first availability.

He’s had a few role iterations over the years. Which one best serves this Arsenal?

For that, I don't think we have to look too far.

Trossard and Havertz have been a dynamic strike partnership that looks more like a “Twin 10” setup in practice. Trossard has floated around while arriving into the box, while Havertz has leaned further right to associate with Saka.

Moving forward, here are a few things I’d like to ensure:

Havertz, Saka, and Timber have access to the right half-space

Havertz continues to have direct access with Saka, providing runs. It doesn’t have to be as much as when he’s played at RCM, just a hearty helping

Havertz has more shot generation and box dominance. You can like Saka/Havertz in direct interplay, but you’d also like Havertz to be home at the far-post on crosses from the same man

More steady and domineering possession throughout

A few more touches in “Zone 14”

More help in deep progression and on the left when necessary

How do we achieve that?

A lot of that comes down to Ødegaard having a passmap that looks a little like Trossard’s did above. If this were a YouTube video, the title would be “ØDEGAARD at FALSE 9????” accompanied by a picture of me pointing and smirking at the text or some shit.

That’s not really what I mean. Responsibilities are more important than the titles of roles. We’ve covered this a lot, but it’s not about changing positions — it’s about unparking him from the right channel, going there plenty but not only there, and having him trigger movements by others into the half-space. Just a little more horizontal and vertical freedom, is all.

The right one, as we’ve covered at length, is my preference to see more often. The top two points of that triangle can be any configuration of Havertz, Saka, and Timber/White.

It’s how the original Bayern goal originated. A slick pass to Saka, a fight from Havertz, and an available space for Saka to fire from.

You can also see it here in the season opener. Ødegaard goes low, Saka pinches in where he’s hard to double, and he and Havertz create an opportunity together.

Floating central should probably be a little less prevalent unless Ødegaard is facing play. This is mainly because Ødegaard’s foot-dominance means that in the most congested areas, if there’s a defender at his back, he’ll pump balls left, but have trouble spinning and delivering back to the right. He’s good at pretty much every scenario in build-up.

The question, then, becomes an interesting one: who gets a “free role,” and why? Watching England, we’ve seen the pitfalls of giving too many players a nominal sense of freedom, especially if they don’t have stable relationships — they step on each other’s toes, and the transitional shape is likely to get carved up. I’d argue we saw a bit of that late against Atalanta — and against Southampton, too. The combination of Sterling, Jesus, Calafiori, Trossard, Havertz, and this Saka, meant that the movements could just be too much; the proximal result is players not home on crosses when they’re fired in. There are also out-of-possession risks.

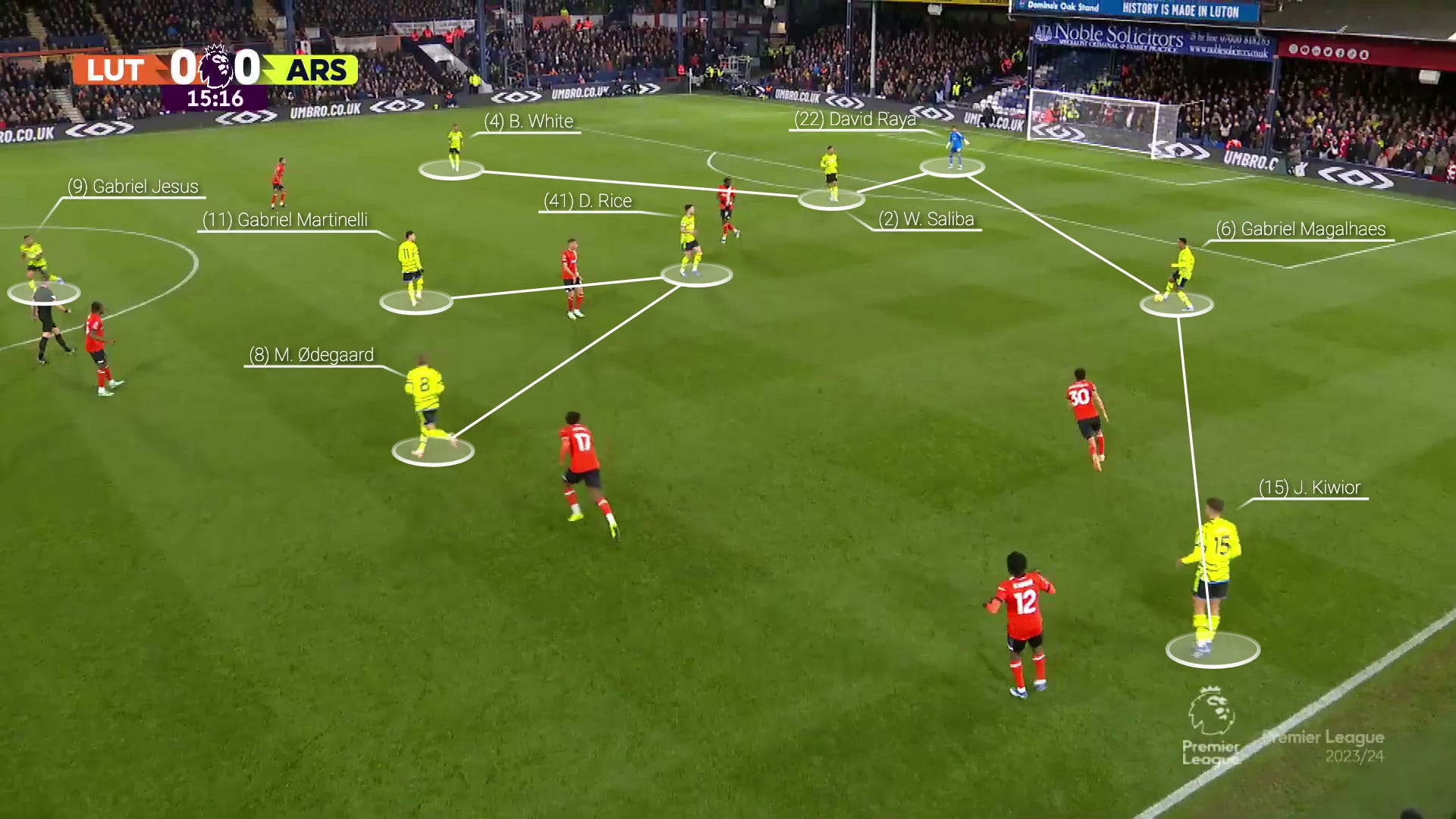

I remember how much I loved watching the rotations in this Luton cage match — but also feeling like it had tipped too far.

That’s a false-9, a false LW, a false 10, a false…

Moving forward, we’ll want to keep tuning the dial as to how much rotation is ideal — which players you want as “stitching” and which players you want standing in an area and running that shit. Ødegaard doesn’t need a dramatic role shift to unlock the above. Just some tweaks.

My feeling is that we are lucky enough to have more than a few players who are fully capable of being fortresses on the pitch, wearily gazing atop an overlook, running an area, however large. Then, you need supply lines to link those up. I always like Ødegaard in that supply line role.

Saka’s got the cannons.

🔥 Some final thoughts

A few spare topics.

I’ve been asked a bit about our veteran cohort. Snap thoughts:

Sterling’s been pretty good. He was tremendous against Bolton and a little harried and imprecise against Southampton; he’s one of those players who you probably get a “fairer” read on when you rewatch in a cleaner emotional state, and he looked nice on second viewing. If you saw his two goal contributions against Bolton (low cross + fast-reaction rebound), those are the kinds of scenarios where he’s at his best. I think both scenarios (goal contributions, messy games) are to be expected.

I thought the physical levels of Gabriel Jesus looked genuinely improved in the preseason after this last operation, but since the groin, it’s been looking more like last year, where his movements feel stiffer. I don’t have a clear read right now, but he hasn’t stamped his name on a starting role.

One light surprise of the early season is how little Jorginho has played. I think he contributed to a better press against Southampton and had a few nice passes there. He’ll be 33 in December, and will be fourth in the pecking order of back-two midfielders, behind Rice, Merino, and Partey. Which is about right.

Writing for The Athletic, Art de Roché has a nice piece about how Arsenal prepare for sequences of matches. There’s a big, interesting one coming up with Bournemouth, Shakhtar, Liverpool, Preston, Newcastle, and Inter on the horizon. We’ll learn a lot about the team then. Here are a few of my thoughts:

I’m flexible about setups against Bournemouth, but I imagine the most likely scenario is a Rice/Partey double-pivot, Calafiori floating around, and a Trossard/Havertz strike partnership.

That said, I think one of the primary focuses of this period should be giving Merino the significant run he needs to build strong associations on that left side. This can be in two iterations: him as a double-pivot, with Calafiori jumping ahead of him, or him as a muscular High 10, essentially playing like a Havertz/McTominay type up top.

I’d like to see Nwaneri against Shakhtar and Preston. At some point soon, I want to see what Rice, Merino, Nwaneri look like as a trio.

I’d lean toward a bullying midfield of Rice, Merino, and Havertz against Liverpool. Pressing can be a great playmaker, and if that one bangs as it should, it’ll be a contender for the best press in the history of the world. I’d want as much size and ground coverage as possible in that one. If lower build-up fails, teams are forced to go long, and that sense of pressing commitment can lead to the higher possessional dominance we still seek.

I’d push for huge rotations against Preston, but for as much stability and clarity as possible in the other matches.

The full-back selections will be based on availability. I’ve been worried about overworking Timber. Some Tomiyasu time would be nice.

I have another piece I’m working on. I’ve been taking a step back on Declan Rice and seeing where and what he does best. You’ve probably noticed the hints throughout. Stay tuned.

The team is unbeaten in all competitions. A lot of connections are still early in their lifespan, and while that’s reason for hopefulness, some injuries and a tricky fixture list will ramp up the pressure for solutions to be found quickly.

We’ll have a lot to take in. At least, until the next international break 🫡

The sickos are here and we are ready for the Merino/Rice/Havertz midfield against Liverpool

Whilst the content detail & insights are of course incredible and fascinating, it's your writing style/tone that just makes me read the whole thing with a smile on my face. Thank you!