The price of adaptation

What we've learned about rotations, pressing responsibilities, and build-up so far as the new players settle in and a new level is sought

"In times of change, learners inherit the earth, while the learned find themselves beautifully equipped to deal with a world that no longer exists." - Eric Hoffer

We all have our roles in life. It is the job of the player to shoot for perfection every time out, knowing full well they are unlikely to achieve their aims, but relishing in the pursuit. It is the job of the fan to complain about the weak mentalities of said players, then go “AHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH EDU OUUUT” at the first sign of bother.

How are you doing? I hope this BBQ finds you well. I write to you a couple days after a disappointing 2-0 loss to Manchester United in a sold-out and raucous MetLife Stadium. I don’t know about you, but whenever I see sloppy drunk dudes fighting over some bullshit, I think: these men are tough and cool. Their cause is likely noble. They are the best of us.

The game itself was sloppy as well. It featured embarrassing mistakes, 37 fouls, and a spray-painted green toupée of a pitch. Many Arsenal fans found themselves a little forlorn in the aftermath. As we covered at the outset, this is a fan’s natural state.

Right after the loss, I tweeted that “the system is such that when you lack a bit of sharpness you can look 20% worse.” I’ll tell you what I mean by that.

Last year, after the title was cooked, Arteta made some likely-overdue changes, throwing Kiwior into the RCB slot, inverting Thomas as an RB, and Jorginho at the #6. Playing Nottingham Forest in the unveiling of this formation change — two months and a lifetime ago — the team gave up an early goal off a mistake, and was never able to crawl back. It capped off a disappointing run of form.

After the game, however, I did a post-mortem none too different from the one you’re reading. In a calmer viewing experience, one could quickly spot how marginal the issues were. In a new shape, with new connections, passes were a fraction of a second late. In the Premier League, that makes all the difference in the world.

Here, Saka had been doubled and dragged two defenders wide, and two defenders were also accompanying Ødegaard, which stretched the block and opened lanes for Partey:

…but the pattern-recognition took a moment too long to develop, and by the time Jesus makes his run and Thomas slides it in, it’s been intercepted:

Such moments were all over. You may recall Benjamin White having 117 touches in his re-entry at RCB, often waiting with his studs on the ball for some more immediate movement to appear.

Meanwhile, there were gobs of almost-on little goodies, including the right-back-underlaps that are now looking a little familiar as Timber embeds himself into the squad:

Here was a recap:

At their best, Arsenal exploits timing. Their movements and passes are immediate. When there is simply a beat of thought before a pass is sent — as there often is when players rotate in — there are compounding effects. They need to work on making this crispness more personnel-agnostic.

Sound familiar?

Now, for the optimists among us, the good news is what happened the next time out. With one more week together, the gang reunited, and abra cadabra — the timing was there, and so was a 5-0 thrashing of Wolves to complete the season.

The system, indeed, is predicated on intensity and sharpness. This summer’s moves have been about ensuring that can show up with more consistency, more variation, through a deeper well of players.

That late-season switch was a different situation, however: Thomas was long-familiar with the Arsenal system, and Jorginho had been running the 6 forever. Now with more ambition, and the upheaval that Arteta believes that ambition to require, the path to sharpness may be longer than a week.

With that, let’s go through some moments in the game, and try to deduce what is a normal “settling in” process, what may take some time, and what may not work.

Focus I: Fluidity on the right

In the attacking phase, at least, the game didn’t start off too poorly.

As we’ve covered previously, inversion does not only impact build-up — it has knock-on impacts throughout the pitch, with the ball and without it. When Zinchenko is on, progression can bend that way, or every which way, and the Martinelli side can turn relational and rotational in the advanced third — with Jesus flowing around, Martinelli cutting inside, and so on. On the right, then, things will be more straightforward up front: Ødegaard will park a bit, Jesus will help less, and Saka will look to dominate 1v1 with the assistance of an occasional White overlap.

When inversion comes primarily from the right, those dynamics change — as we saw in the Thomas underlap above. Last year, how many times did we see White sprinting under Saka through the half-space, and Ødegaard supporting behind? Not many.

The initial signs here are promising, and as somebody who’d like to see Saka more in the half-space, and Ødegaard a little less tethered to an area, I’m all for it.

Early on, Timber accepted a ball from Ramsdale with his head, and showing good anticipation, blasted it into space for Saka to run into:

A minute later, Timber took the ball into the corner, Saka de-marked his man, and the two created a slick double-chance for Martinelli which should have been driven home:

Let’s see that in .gif form:

This is especially intriguing when you consider one form of Arsenal kryptonite: going 4-5-1 (or 5-4-1) and doubling Saka on the wing. Timber’s movements here will work to unsettle such tactics.

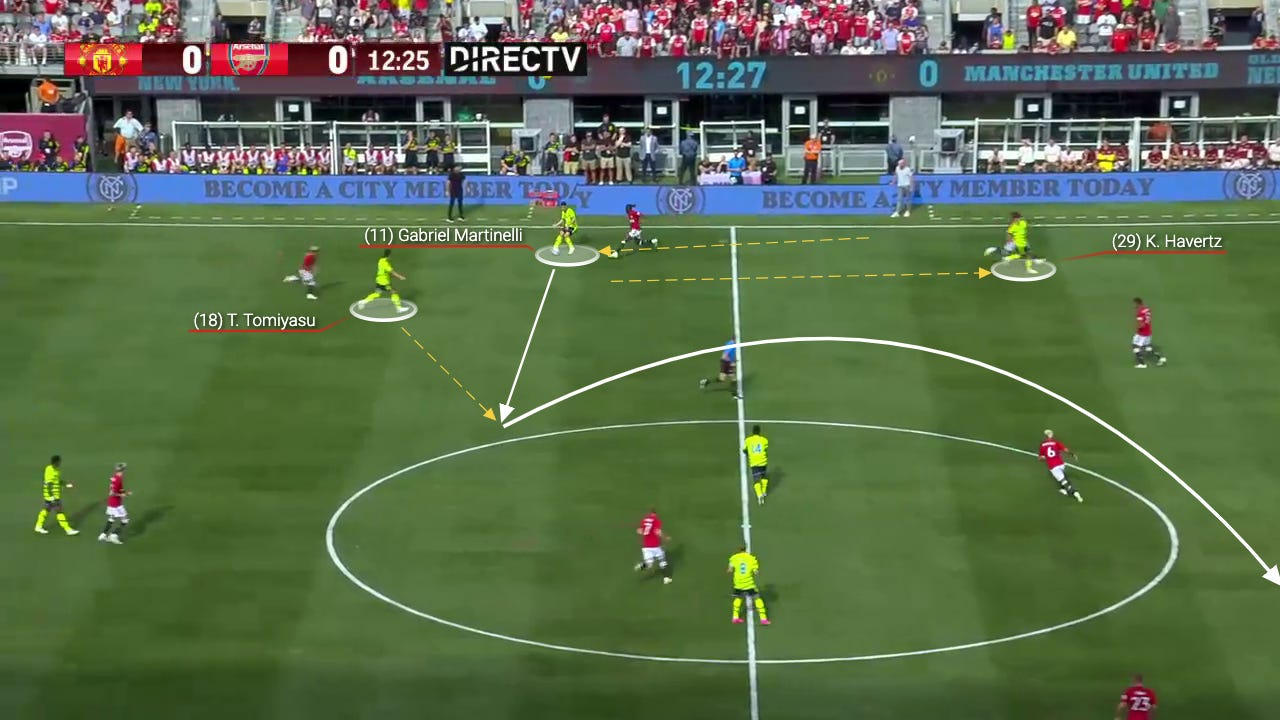

Elsewhere, there was more reliable work to get Saka isolated, originating via some quick interplay on the left. Tomiyasu looked nice and spry, and Havertz was dragging runners — followed by a switch out to Saka in space. Despite their high-possession, Arsenal were 14th in switches last year, and nobody accepts a switch quite like Saka.

There was some awkwardness and growing pains, however.

Let’s first see how that showed up out-of-possession on the first goal.

Focus II: Pressing and covering

To better understand how the first goal came about, let’s take a simplistic view of the Arsenal press shape when the opponent, in this case United, is playing out the back.

As you’ll see below, the striker will take an angled route to try and guide the pass to a desired side — here, that means away from Martínez and towards the right, which nominally holds Wan-Bissaka and Varane — and the mostly man-marking shape generally looks like a high 4-4-2 or 4-1-4-1 on paper, but the nomenclature doesn’t really matter. It’s more about their individual responsibilities:

As you see, the #6 (Rice in this diagram) has a lot of responsibility here, especially as the full-backs jump up to support the front five. This is what we mean when we talk about Rice being a “platform” signing. His presence should, in theory, allow players to push up — and not just when attacking, but when pressing as well.

In a man-marking scheme with some hybrid components, there is one lasting advantage to the adversary. They can drag certain players to a location of their choosing, and in particular, they can seek to exploit the loneliness of this lone six to their own ends by going long.

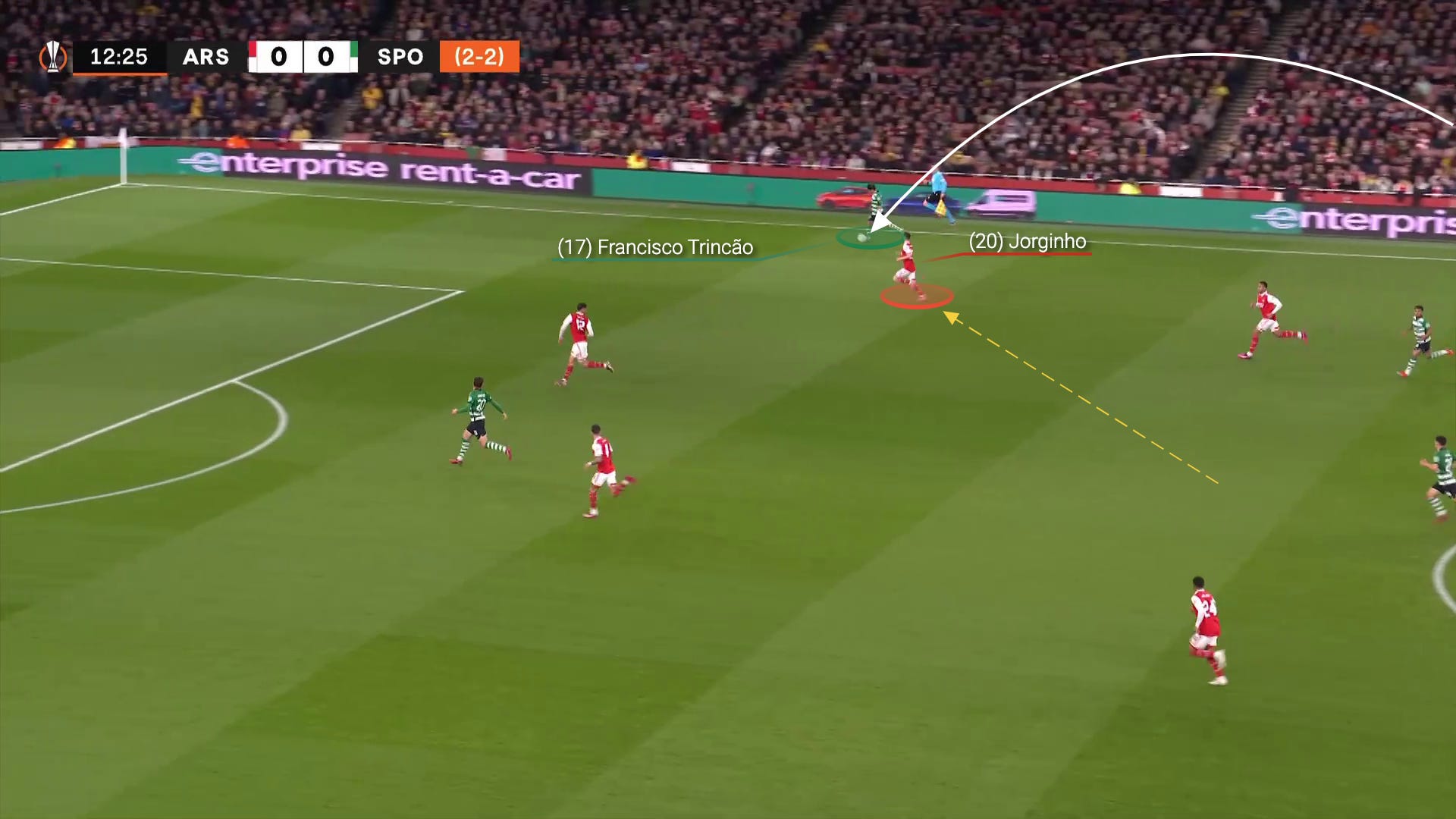

Not to pick old scabs, but you may remember Sporting CP and their own bright manager (Rúben Amorim) targeting this in the Competition Which Shall Not Be Named. The Portuguese squad would play out the back for a few moments, dragging defenders forward — then, with Jorginho patrolling the entire middle, they’d send their 10-ish central midfielder (Pedro Gonçalves, whom I love) on a run to drag him into a cavern and beat him on pace:

They did this in the return leg, as well, sending Trincão flying around, and making Jorginho track the wing — which opens up all kinds of possibilities:

In the 4-1 beatdown against Manchester City, you’ll remember the balls that went direct to Haaland, before bouncing to a corresponding run by De Bruyne, stretching the responsibilities of Xhaka and Partey to a point of bursting.

The burden on the Arsenal #6 was clearly heavy on Erik ten Hag’s mind for Saturday, but in different ways. Looking back on his Ajax teams, you would see some truly oddball build-up rotations, full of weirdo first-phase fluidity that you don’t often see from more disciplined systems, or truthfully, in a lot of places. His strategy against Arsenal was fairly clear: rotate in build-up to pull Rice around and into space, go long to manufacture a transition, then have runners attack the vacated middle.

It’s important to note that, in most cases, this is all anticipated and expected by the Arteta tactical design. If you look to have an ambitious press, that means pushing players forward, and that means trusting your backline’s composure and your defensive midfielder’s ability to patrol wide spaces. Hence, the Rice signing.

Within the fourth minute, Shaw played a long-ball over the top to a sprinting Bruno, who had timed the offside trap brilliantly and galloped into space like Gonçalves in the screenshot above. The difference here from the previous Jorginho examples? Rice was beat, but still managed to get back and gain position on Bruno, blocking his angle to goal, and delaying the attack long enough for reinforcements to arrive:

A shot did come off, though — with Bruno passing it into the middle, and Antony flubbing it. Still, this is generally a risk that Arteta is willing to live with, and, be warned, is a situation that will continue to pop up a bit. A cascade of factors all have to go right for the opponent to exploit this situation: they need to hit a perfect long-ball, get past the offside trap, beat Rice, then beat Saliba, then beat Ramsdale.

Which reminds me: where the fuck is Saliba in this picture?

I rewound to watch the makeup of the play, and during Shaw’s outlet ball to Bruno, I caught the blurry image of two players on the touchline with Garnacho. Maybe I’m missing something, but I truly have no idea why Saliba is up here. Timber was already there when the play reset, and had no reason to get pulled inside — though perhaps they could be working together to plug the lane of a ball straight to the furthest line. If I had to make a guess, sans evidence, I think this is just likely a new-teammate miscommunication, with an uncertain culprit:

There’s reason to believe that these situations — an ambitious, untethered attacking midfielder pulling defenders around — could lead to a renaissance of the #10 position in the world game, as the role is well-suited to put pressure on the more en vogue pressing philosophies of the time. Welcome, Kai Havertz!

Back to the goal, which has several interesting characteristics.

The play started back here, with Manchester United recovering possession in the midfield, and opting to reset and play it out the back. As their team gets back into build-up shape, Arsenal pick up their covers. Without Ødegaard or Havertz front-marking Kobbie Mainoo there in the middle, Rice jumps up to follow him. What results is an almost disarmingly simple man-to-man system, with Bruno kinda watched by the two Arsenal CB’s at this point:

With Mainoo understanding that he is picked up by the guy they want to drag, he darts out all the way to the touchline (out of picture), and fills a zone usually occupied by Antony. Bruno drops deep into Mainoo’s zone to help with build-up, directing traffic, and getting passed back-and-forth between Havertz and Ødegaard:

And after a long moment to consider, keeper Tom Heaton blasts it long to Mainoo, a build-up midfielder who is now sprinting down the line. Rice, who had picked him up on the reset, makes the decision to see the play through. Tomiyasu, who was watching Antony, now sprints down to cover:

…and that’s the pivotal decision. Throughout this pressing sequence, there are no hand-offs or coordination, just schoolyard-simple man-marking — which United likely expected. Fernandes, who was lost when helping with build-up, now races into the zone Rice would usually occupy, and finds it open:

…and small moments happen next. Tomiyasu doesn’t close down aggressively enough; Havertz tries to help but has a looping angle; Gabriel, a wonderful shot-blocker, doesn’t shade his blocking shape to the far post; Ramsdale has a late and clumsy reaction; and Fernandes fires off a perfect rip. Goal, United:

There are a few things of note here. The first is Rice’s decision to fully track the runner on the wing. I think that is often the correct and unavoidable decision; Thomas could be seen doing the same in the second half, and this is part of the tactical game, especially when Zinchenko freelances up the pitch.

But as comfort builds, more complex determinations will likely be made. In this case, I think Rice could have noted that the box was adequately covered, Antony was out of the picture, and Tomiyasu had time to swing out to meet Mainoo — while Rice stayed and protected “Zone 14” entries.

The final bit to note is what happens when Rice is pulled out wide, as will inevitably happen. In that case, everybody has to make an especially-fierce effort to sprint back and fill the top of the box. Whereas we may associate that heroic run with a Xhaka, his successor in the left-8 role is looking to have a different, more advanced role in the press — he’s the high man, alongside the striker.

This all puts pressure on two levers: A) Rice to “sit” more and trust some hand-offs (and better teammates) with increasing frequency, and B) Ødegaard and others to Get The Fuck Back, all the way to the box, as soon as Rice shows that he’s out of the middle.

But more than that, it’s in all the little moments of communication when determining marking responsibilities. Make no mistake: Havertz and Rice figure to be upgrades to the Arsenal press, and probably big ones. They are just joining an entrenched philosophy and have some new habits to build.

These moments can be covered, they just require a little more sophistication than was on offer on Saturday.

Arteta’s got a beautiful new couch. All it lacks is a proper ass-grove.

Focus III: Build-up

With Zinchenko out, and new signings settling in, Arteta went on an information hunt. For most of the game, that featured a Rice-Timber double-pivot. In second-phase build-up, it might look something like this:

With a box-y midfield, I’ve helpfully added the star emoji to players who have joined in the last couple weeks, and were making their first appearance as a group.

In practice, the shape looked something like this:

I’d say it went about as expected. There were plenty of moments of skill and fluidity. Timber, schooled at Ajax, looks immediately comfortable and confident floating around at will. As we saw last week, he is not starting from a conservative place and then working his way towards swagger — like Zinchenko, he’s doing what he wants.

Still, that leads to moments of adjustment. Here, he swung through the middle as usual, opening up a spot for Nketiah to drop deep — but then he and Ødegaard dropped into the same zone at the same time, making their efforts redundant. When Arsenal was at their best last year, there was more of a mind-meld:

Rice looked a little bit like his England self: active, available, communicative, but ultimately, conservative. He went 23/24 (96%) passing, going forward five times, and generally just kept things chugging with accurate one-touches:

He is yet to feature with an inverter from the left, so it’ll be interesting to see how his range fares over there. He was not without moments.

This ball to Havertz is probably what people are hoping to see:

He also used his carrying ability to manipulate defenders and ping the ball up to a dropping Eddie.

It’s early days, it’s a difficult role, and we saw nothing particularly alarming — so patience is definitely in order. One thing that will be worth keeping an eye on is the development of the Timber/Rice partnership. I have few concerns — in fact, the opposite, pure excitement — against low-blocks. Timber can unsettle, Rice can cover, and any of the concerns about back-to-goal first-phase work will largely disappear. Once Rice turns in the middle third and has the whole pitch to survey, he’s already as good as anyone.

In the first phase against a good press, though, Zinchenko is a big void to fill, and will be difficult to unseat. While Timber and Rice can be dominant, safe possessors, they’ll also need to ratchet up their risk-tolerance and ambition ever so slightly during build-up to blast in line-cutters at the right frequency. Rice will have to build comfort with an actually talented on-ball partner in the pivot. You want recycle-recycle-cutter, not recycle-recycle-recycle. It’s not an unfounded concern, and something to watch.

This build-up is mostly an ancillary responsibility of new signing Kai Havertz. I tweeted before the game to “Brace yourself now: there will be games where Havertz does a million off-ball runs, pinning and dragging defenders around and creating space for others to shine and win — but we’ll hear about how he was invisible or not involved, etc.”

The quality of his game, like even Xhaka before him, will be dependent on the build-up play of others. This is because of how Arteta largely views the role. Here’s what he shared with Jamie Carragher when discussing Xhaka’s move forward:

“It was a necessity. The squad wanted to evolve to another level and be more dominant and have more resources in the final third to score more goals. I spoke to him at the end of the season and said, ‘I need to unlock something in your brain because you’re so comfortable and confident playing in this area that you have forgot that actually what is going to win us the game is here. The team now demands somebody here."

When you compare Xhaka’s updated role to Havertz in his career, you’ll see a lot of similarities, with Havertz predictably getting the ball a bit further forward:

But the days of that LCM completing 80 or 100 passes are largely behind us.

It is natural, and human, to seek a more rounded 8 in this role. Nobody suggesting it is silly or wrong (and I’d still like somebody who can play over there for matchups and depth, in fact). Especially prior the Havertz links, I was game to give Rice an adjustment year in both spots before likely taking over at the 6 from there. I still would like to see a Rice/Thomas pairing through the middle at some point, and think a 4-2-4 with Havertz looks mighty promising against the best-pressing sides.

But we must be conscious of all the dynamics in play. In the Pepification of All Discourse, we might see the example of Manchester City and seek a similar profile to a Kovačić or Gündoğan. But all other variables are not constant.

For one, Rice projects better in defensive coverage than Rodri, enabling a slight lurch forward for the others. Elsewhere, Arsenal’s wingers want to cut inside more instead of dribbling and retaining it, and Martinelli, specifically, wants to get central. Plus, Ødegaard may have unlocked potential in deeper build-up.

But most importantly: Haaland and Jesus are fundamentally different players, and this impacts the responsibilities of those around them. While all the focus is on the gap in their finishing ability, not every advantage is in Haaland’s court. Jesus got 46.2 touches per 90 last year; Haaland had 24.8. Jesus offers about 80 more yards of progression over Haaland. He also has three times as many recoveries, and a huge advantage in terms of raw defensive output: literally ten times as much (1.92 tackles+interceptions per 90 to .19).

What does this mean? First, Jesus fills much of the gap in build-up touches. Second, Arteta is building something different, and it must be understood as such, because his model will continue to deviate from Pep’s.

Rather than strict positions, it may be more helpful to look at “potential time spent in certain attacking zones.” Here’s a bullshit way of looking at how their rotations could be divvied up. I made it all up in five seconds with my own big brain:

Put better: Jesus is a striker who is kind of a midfielder, which helps Havertz be a midfielder who is kind of a striker. This is not haphazard — this is the best use of their respective abilities.

Yesterday, Arteta both defended the team’s physicality — and stressed that he had options at his disposal:

“You use the word ‘physical’ but if I put Granit and Kai (together) who is more physical? He’s (Havertz) 1.91m (tall). It depends what physical is. Physical is to run, to run in behind, run forward, to tackle, to defend. He will fit in with the qualities we have for sure and the good thing is that we have options in midfield. When we want a game to become more physical we have the options to be very, very physical.”

He ain’t having any of your panic.

Other notes

I actually had a lot more to talk about, but this article is getting wildly long, as always, and I’ve got to head off, so it’s best I wrap it up now.

Here were some other notes:

Perhaps the most interesting tactical stuff happened late in the game, with a “fill in the blank pivot” alongside Thomas, then Jorginho. As a right-back, Thomas stuck out wide, and Jorginho was joined by Tierney, then Ødegaard, then even ESR rather than the more obvious choice. Earlier in the game, Tomiyasu also shaded through the middle, and Kiwior is capable of these movements as well. At the Athletic, Jordan Campbell covered all this optionality perfectly. It’s so interesting.

As such, Tierney wasn’t strictly an inverted full-back, or strictly a touchline bomber, or a back-three defender — he was whatever he wanted to be based on the situation. He felt freer than he has in a while, and is genuinely starting to look like he could be part of the plans.

When inverting from the right, the dynamics of the backline are an unresolved question, in my eyes. In any ideal situation, you want Gabriel as a front-foot defender out wide on the left, Saliba as the fun-killer in the middle, and White (or even Timber) on the right. With Timber joining and inverting, Gabriel becomes the central force, which may limit him from what he does best, and amplify some of his impulsiveness. I’m a sicko, so am anxious to shift that option over to a backline of Timber-White-Saliba-Gabriel; the back-three of White-Saliba-Gabriel is already conclusively proven, and Arsenal are rarely low-blocking anyway. It does feel a little goofy to have Gabriel out wide, I’ll admit, and this question may be one of the many reasons the Zinchenko option is preferable.

Emile Smith Rowe got a lot of plaudits for his u-21 EURO performances, and it was great to see him back and injury-free, but I may have been more measured in my take-aways: he still looked a little blocky and tired to me. In his cameo on Saturday, rotating wildly with Trossard, he looked to have more burst than I’ve seen in over a year. Now that the left side is looking to be the more advanced one, he may be sneaking into an ideal situation. His dribble-burst to break a press might be a trump card on Havertz in certain situations.

I’ve got a lot of thoughts on Vieira that I’m probably going to save for a full post.

Analysis: Ramsdale was quite bad.

Elsewhere, two notes:

I made my debut at SCOUTED this week with a long-read on Brighton’s operations. Read, subscribe, enjoy!

Thank you to Jon Mackenzie of Tifo for helping me make sense of what I was seeing on the pressing front in this one. Go follow and praise the GOAT.

In conclusion

Pre-season is about learning. For as much as we’ve learned, the team has learned more.

Last year, Arteta was able to solidify what dynamics work best for the first XI, but ultimately found himself short of depth and optionality to execute it. While there can be an impulse to soldier ahead with previously-won truths, sometimes, the risk of stasis is greater than the risk of change.

This pre-season is about finding out what else works, and how. If we know Arteta like we think we do, he’s got plans — on top of plans, on top of contingencies, on top of plans. But the players have plans of their own:

“Sometimes, you have to leave players on the training ground to see because sometimes when they train with each other they give you a lot of information. It doesn’t always have to be you provoking information. They give you information as well and you have to be ready to take that.”

Some pairings may gel or not. Some injuries may happen. Some surprising things may appear that shift the strategy.

In all, if there’s a plan, there’s no time like the present to put it into action. If things aren’t working, you can adjust, but we’re far from having enough data to make such a determination. One shouldn’t negotiate against one’s self.

The price of adaptation, particularly right now, is almost nothing.

Tranquilo.

I cannot believe I read stuff this for only $5 a month wow

A great read as per. Please be gentle with my friend Fabio 🫨