Triangles

With more options, selection gets harder. Who unlocks who?

“When you see him like that, you don’t have to worry, because that’s not how it’s going to be for you. You’re not going to be one of these people who goes through life wondering why shit keeps falling out of the sky around them. I know that. I know it. OK?”

— Michael Clayton

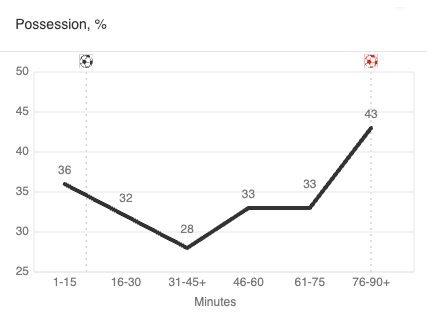

Since we last spoke, only a month ago now, we’ve looked toothless and goalless in a draw against Nottingham Forest, played Inter off the pitch at the San Siro, lost in angering fashion to a clinical United, indulged in beautiful 3-2 slopart against Kairat Almaty, destroyed Leeds 4–0, vanquished Chelsea from the cup in cagey-then-riotous fashion, popped on our handmasks for a second-half Gyökeres brace, felt deflated again at Brentford, and regained some joy in the FA Cup. There have been own goals turned olímpicos, injuries and returns from them, lineup consternations, familiar concerns in attack, explosive celebrations, yellow cards for sarcastic laughter, annoying City comebacks, and meandering rants from humanity’s most smooth-brained pundits. There have been understandable recriminations and their worthwhile rejoinder: Arsenal still sit atop all the tables.

In a previous, pre-cloud age, this file would have been titled newsletter-final-v2-final-FINAL-v4-final.doc. I’ve done a lot of writing and rewriting and deleting and rewriting during all this. In keeping with the times, we are presented with a new swipeable story or stimulus every minute. Oh, Kai is back? And gone again? Why isn’t Merino on the bench? Oh, we signed an 18-year-old Scot? And a Stoke defender? And Dowman? Why is all the data on fbref suddenly gone? Why is Liam Delap playing right wing against us? Is that Saka in the #10? Did Arteta just do a second-half goalkeeper change?

“There it is again,” Bo Burnham sings, “that funny feeling.”

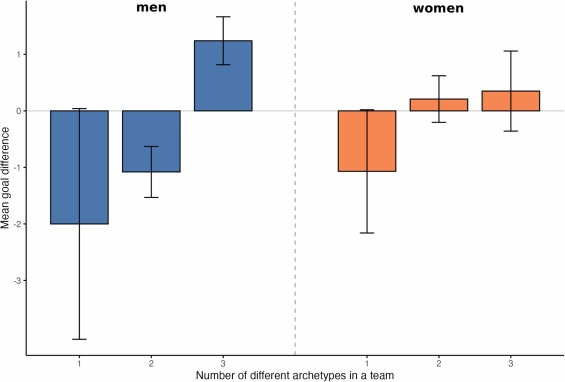

A couple of weeks back, Jon Mackenzie linked to a study titled “Quantifying individual and teammate effects on small-sided football performance through repeated-game observations.” In it, researchers had 31 players compete in 3v3 games, then repeatedly reconfigured the teams to estimate the effects of different groupings. The findings were interesting.

[T]eammate combinations explained more variance in team success (20–23 %) than individual players (11–12 %), though substantial residual variance (64–69 %) indicates performance depends on multiple factors beyond these measured effects.

Continuing:

We found that while individual players contributed meaningfully to a team’s goal differential (11–12 %), their impact was consistently outweighed by the effect of teammate composition (20–23 %).

In short, teams won more because of how players fit together than due to individual quality.

The other intriguing thing was how much having a mixture of different player profiles may matter. The researchers created four archetypes: goal scorer, team catalyst, defensive specialist, and role player. For men, at least, teams composed of three distinct player archetypes outperformed less diverse teams.

The scope of this project was fairly limited and should be kept in proportion.

Still, it makes sense, no?

This effect is most pronounced in international play, when coaches have less time to create marginal gains through endless drilling and tactical detail. There are shotgun marriages throughout the pitch, and as a result, underlying player characteristics matter more and are harder to override. If your eleven doesn’t have a fundamental complementarity, it will be sussed out.

(I fully expected “complementarity” to get a red squiggly line under it. But apparently it’s an actual word.)

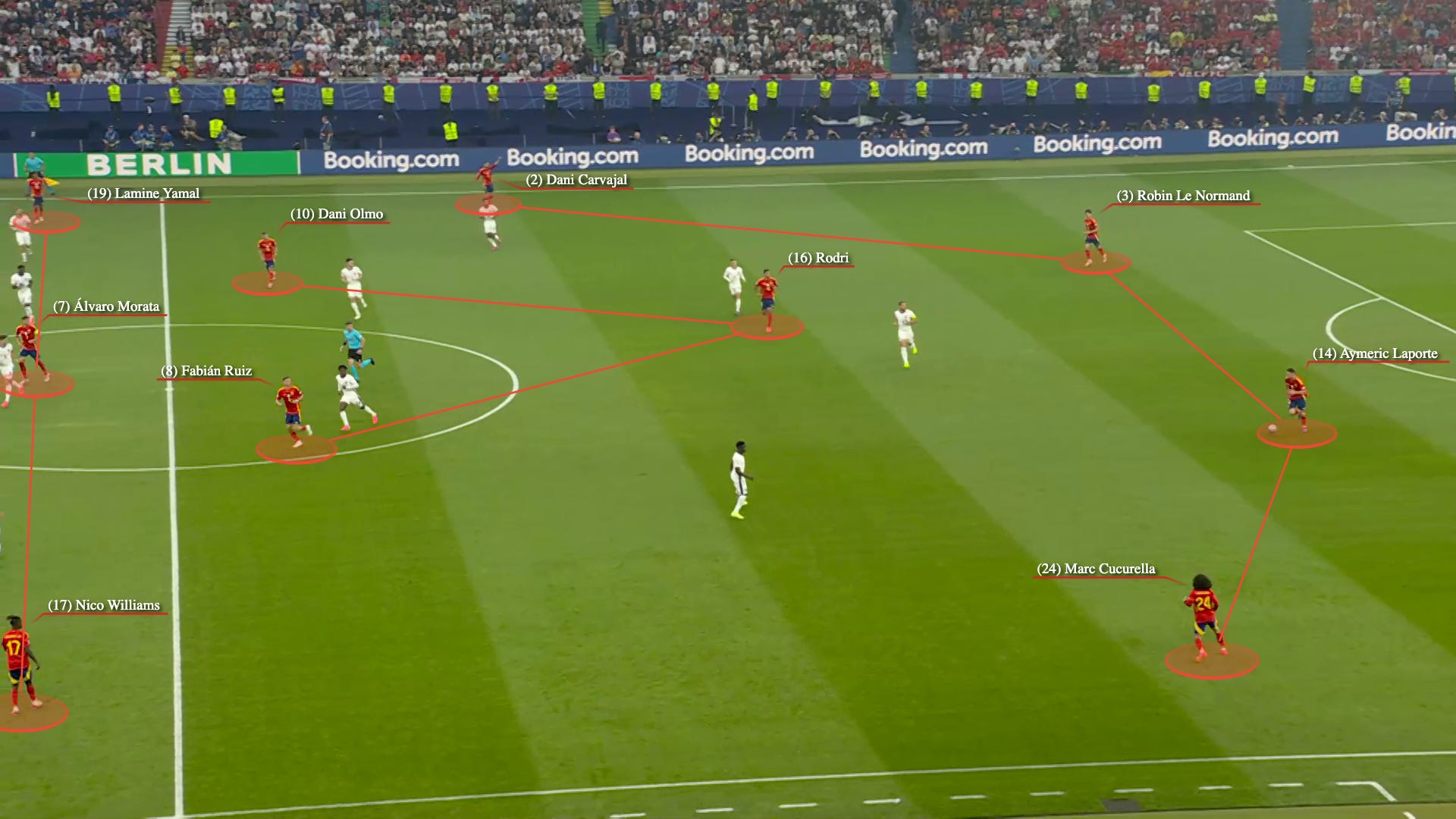

In the last Euros, we can remember the ramrod efficiency of the Spanish eleven.

This was just a group of players standing where they should be, and doing things they were good at. End-of.

Contrast that to the England side, who would often slap redundant profiles together. I remember Kane, Bellingham, Rice, Mainoo, Foden, Saka, and a wrong-footed Trippier all requesting the ball to their feet, vying for the same 20 square yards of grass.

Many stars can still generally succeed in such an environment, but few can reach their full potential without the surrounding conditions helping make it so. As in life, we are heavily impacted by what is around us. And lineup composition is a tricky, mysterious trade.

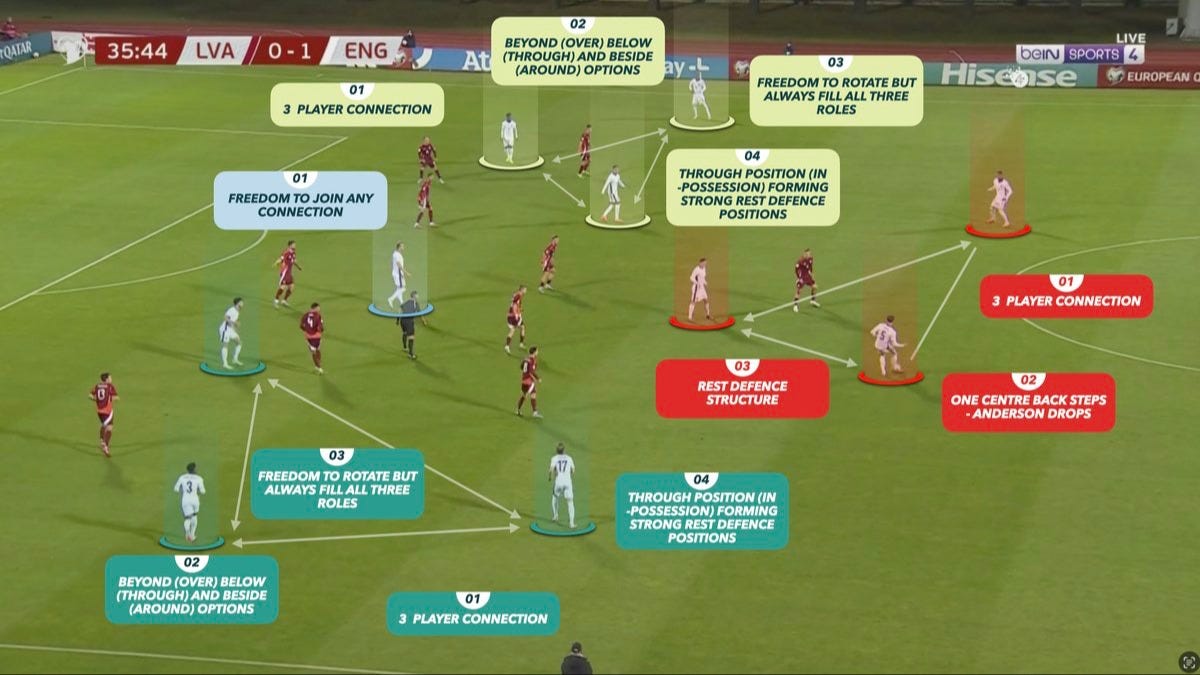

I’ve written for Tactx in the past, and the bright minds over there often talk about the “Three Connections,” which they observed at La Masia. Once you start seeing the game this way, it’s very difficult to unsee it.

For England, Thomas Tuchel’s tactics so far have been fairly easy to digest, which, for me, means they are easy to admire. I prefer international tactics that are devastatingly simple. The quicker you establish a firm tactical identity, the sooner you can hammer home the details that make it hum.

In the above study, we saw how conjoining profiles reign supreme in 3v3 games; when you look at a wide-angle view of the full 11v11 pitch, you start to really think about how those 3v3 player groupings enhance or detract from one another. In these early days, you can see those roaming groupings, with Kane empowered to join any at will.

The players form the rest shape, and also ensure that there is a “below,” “beside,” and “beyond” option at every turn.

When we look at passmaps, it’s hard not to think of something like a network or a power grid. In fact, they’re often called passing networks. Those subjects include many relevant sub-topics that I very much understand, so long as you don’t ask me too many follow-up questions.

There’s the idea of load balancing: spreading demand across multiple routes so no single corridor gets overloaded.

Load balancing can optimize response time and avoid unevenly overloading some compute nodes while other compute nodes are left idle.

There’s the idea of rerouting, of parallel paths, of contingencies. When one path fails, it puts extra stress on the others. It can look like this:

I’ve also written in the past about “triple modular redundancy,” a concept in which “three systems perform a process, and that result is processed by a majority-voting system to produce a single output. If any one of the three systems fails, the other two systems can correct and mask the fault.”

For football, this can be extended to depth: you want three possible options at every position. But it can also be extended to balance: you want three routes to every goal: left, middle, and right. And it can also be seen in these recurring triangles throughout the pitch.

There are players who make these kinds of connections easier. Through his return and all-too-soon absence, we were reminded clearly that Kai Havertz is one.

“His main quality is that he makes you (as a team-mate) better somehow,” said Arteta. “The way he moves, communicates with you, gives you information and moves around. He’s a very difficult player to mark, and especially he opens up a lot of spaces for the rest of the players. So I think they’re going to be very happy to have him around.”

The idea that some players quietly lift the level of everyone around them is easy to agree with in theory, but can sometimes be hard to fully appreciate in the moment. Football happens too fast, and we’re too busy looking at the ball, arguing about shots and subs and referees to notice the small mercies that thoughtful players provide us with.

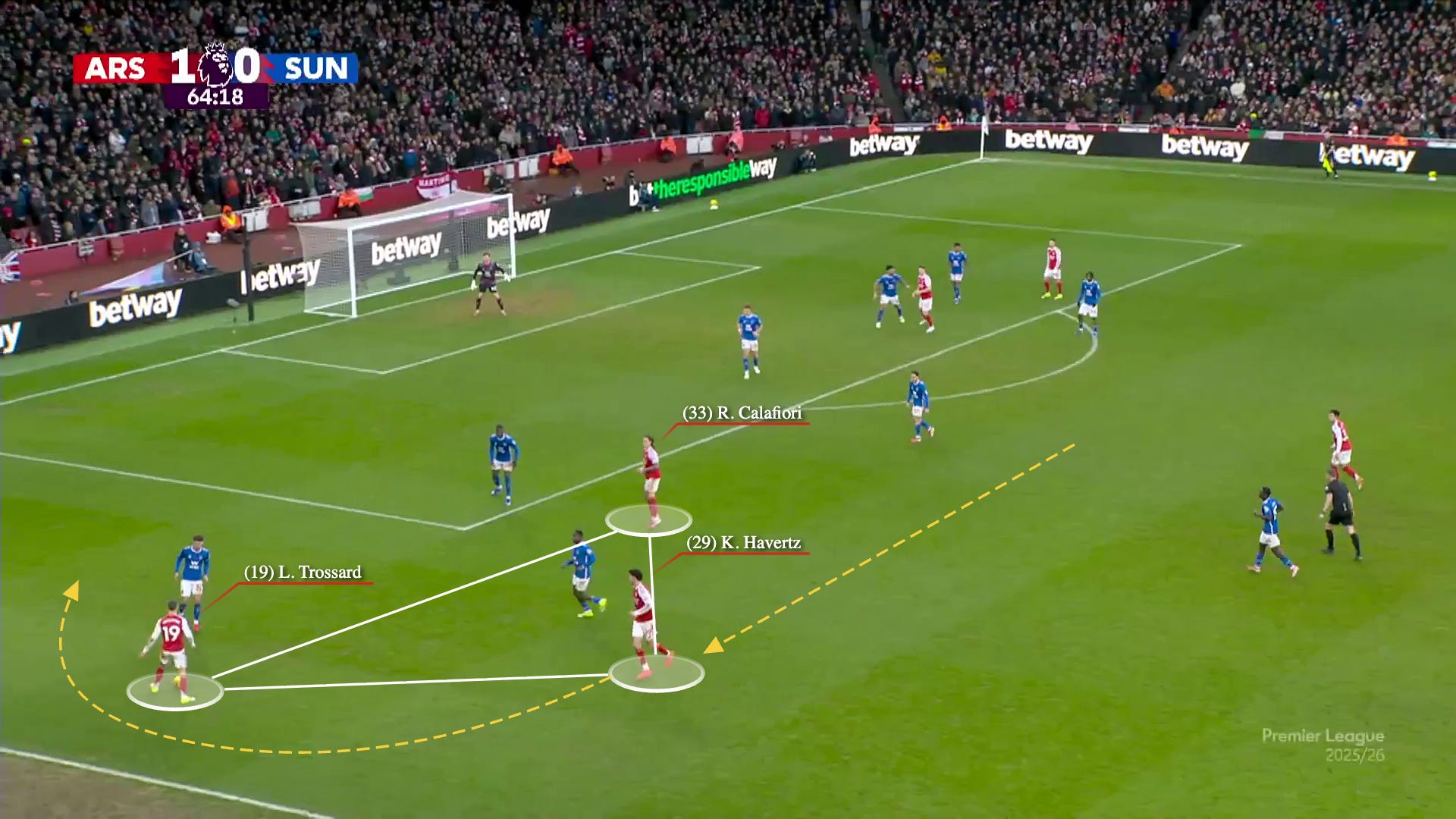

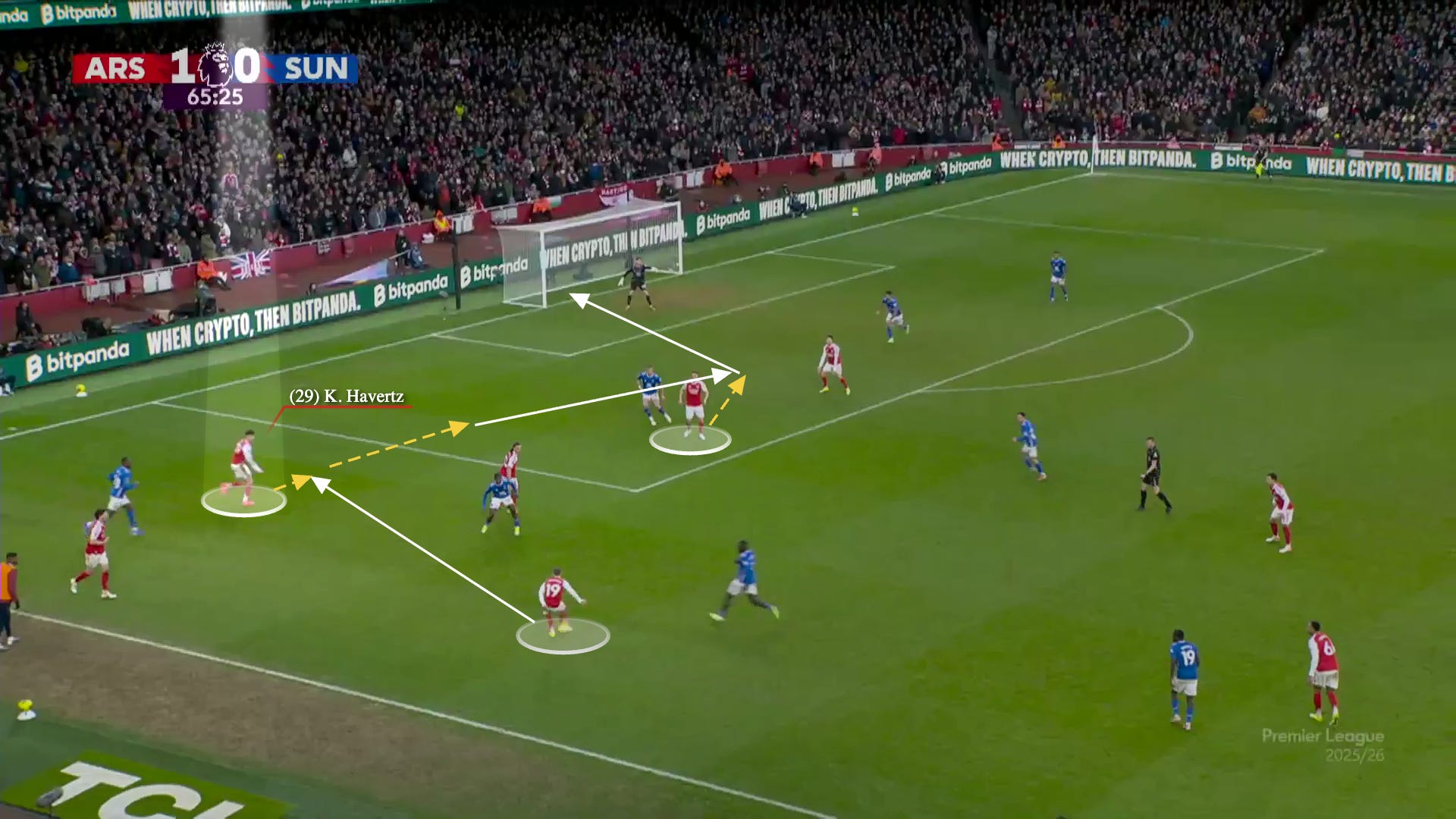

In the sixty-fifth minute against Sunderland, Havertz rolled over from his spot as an “RCM” to join this wide left triangle.

He combined and delivered the ball out to Trossard; in this case, he was the “below” man in the triangle. But this situation also met the conditions of an overlap: because Trossard was single-marked by a stationary man, and the other defender would have to arrive at pace, and force a timely handoff, Havertz could provide the overlap and test their connection.

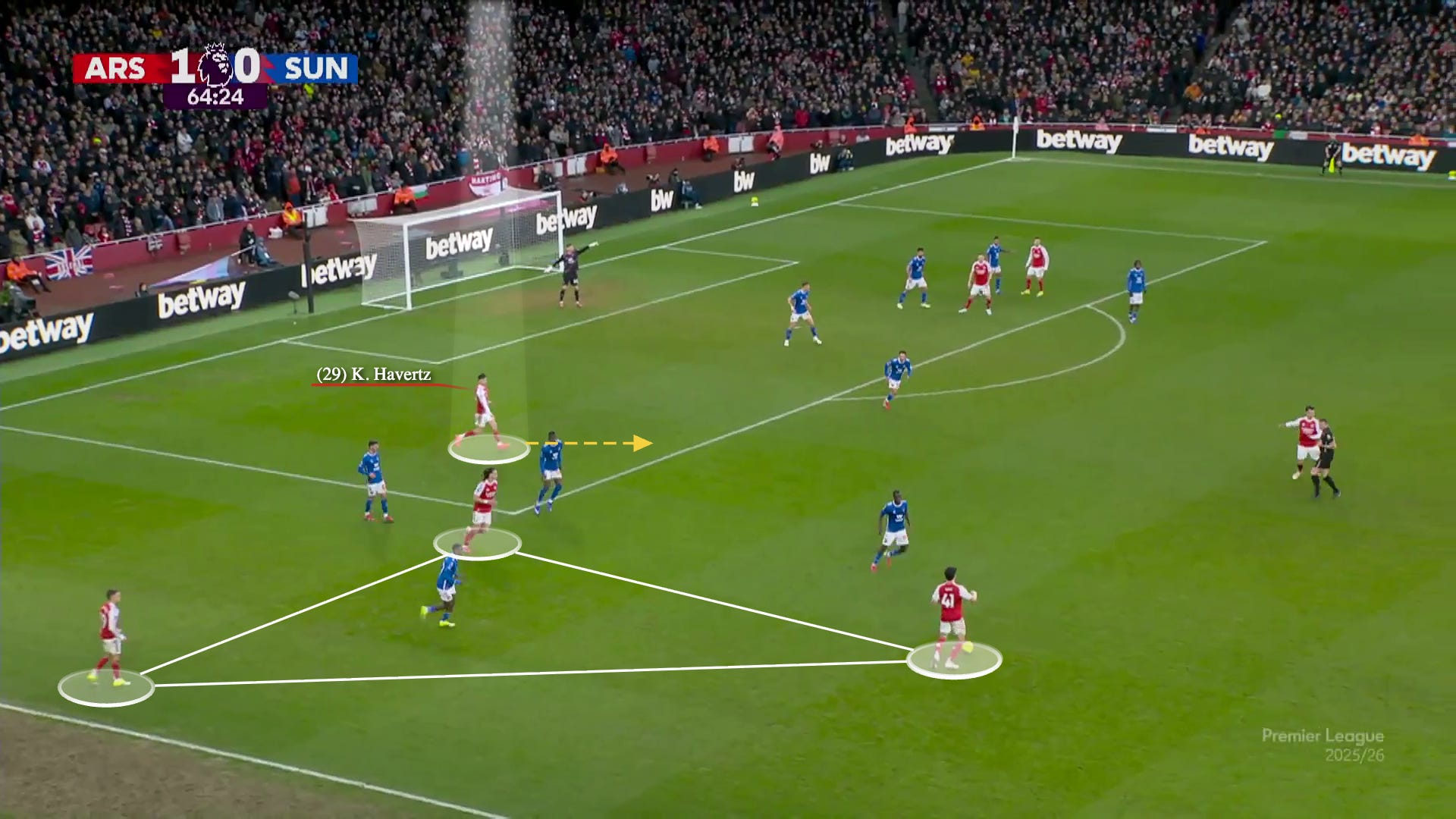

Sunderland responded well, as they do, so Havertz again looped around and provided an option to Rice, who had joined as the “below” player. Havertz was “beyond” as the ball was recycled.

The ball made it out to the other side, which I won’t screenshot for now, but Havertz essentially played the role of a box #9, looking for crosses.

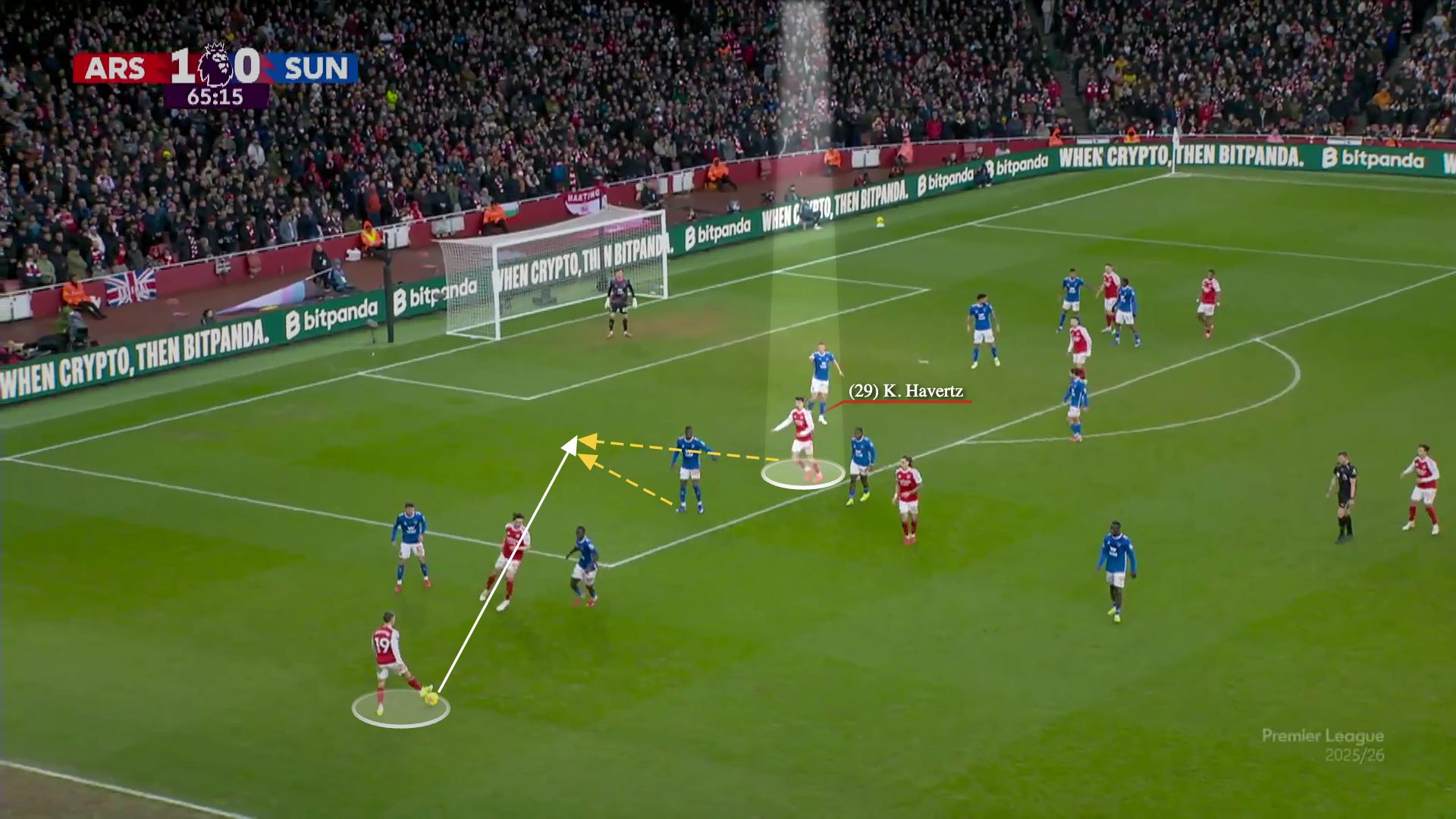

As the ball made its way back to Trossard, Havertz again showed an option: floating back to provide an underlap. Trossard, as he was wont to do, tried another so-called risky pass, but Sunderland were able to jump it.

Sunderland won possession and tried to play out, but Rice and Havertz smothered them. The ball again went to Trossard. Winning on the counterpress is nice for a lot of reasons, but one undercelebrated facet is that the offside line is garbled, and there are more opportunities to sneak around. Havertz ghosted a run in-behind, Trossard hit him this time, and the rest was history.

Here it is, in full flow, with Gyökeres hitting the exact kind of messy striker’s goal one would hope for from the long-awaited striker signing.

It shows just how much relentlessness is required for a goal against a block like this.

Last time, I listed a litany of small grievances about our Arsenal, from the lack of an aerial presence, to pressing follies, to some issues connecting the middle of the pitch. I laid out some of my preferred tactical solutions, but ended it with this.

If you want my simpler opinion on it, it’s this: Save us, Kai Havertz.

Havertz made a brief, teasing cameo against Portsmouth before being put back on the shelf in the name of caution. After that, he made four appearances, playing all of 191 minutes (the equivalent of 2.15 90s), and he tabbed 4 G+A. Looking back, that may be underselling it. It’s almost bewildering how many little plays he made.

He switched his bodyshape against Kairat, ghosting up into the right wing to dissolve into the blindspot, before White hit him over the top.

It led to a footrace with Gyökeres, with the Swede, ahem, screening defenders, before Havertz cut back onto his left and hit it home.

Against Sunderland, Raya freed him up for a fifty-yard carry that almost resulted in a curling Goal of the Month contender.

The Kairat destruction started early, with Eze showing deep (he was defending in the left-8), line-breaking up to Havertz, who delivered it up to Gyökeres.

The pass was similar to the one he later delivered against Sunderland for the narrowly-offside Jesus penalty shout.

What’s the point, besides Kai propaganda? (And isn’t that reason enough?)

Arsenal have a few “below” players, a few “beside” players, and a few “beyond” players. Some, like Calafiori, Saka, and White, can capably float between roles. But none can combine the ability to interplay with the ability to truly gallop in-behind to the level of Havertz.

This “beyond” ability led him to the badge-kissing finale of the Carabao semi-final.

With Merino likely out for the bulk of the year, it’s clear how big a physical vacancy this leaves.

We can hope for his speedy return, while acknowledging the ability to improve elsewhere.

After the United loss, Arteta hoped to see the players perform with more lightness.

“We took a moment to bring the temperature down, to pause, to reflect and ask two questions. One is how do we feel, and how do I feel myself, and then how we want to live the next four months. It was so encouraging and beautiful, because what came out of there is very simple. We have earned the right to be in a great position in four competitions, and in the next four months we’re going to live and play with enjoyment, with a lot of courage and with the conviction that we’re going to win it.”

The return of Kai briefly helped. But looking more broadly, many of these connections we speak of, those little nodes that transmit attacking energy through a passmap, have sputtered this season. Things simply don’t feel figured out in attack, and we were cagey again at Brentford. This subject is where much of the variability in the remaining games will lie.

I’ve never wavered from my optimism about our chances for the big stuff this year. Arteta has generally rotated well, and I have few critiques of how the squad has been deployed in the cups or in the Champions League.

But I’ve also been frustrated with some setups and dynamics in the league, even when results eventually go our way. With returns from injury comes a bigger squad. With more options, we’re less resource-constrained, less obligated to do things just because they’re the only things available. It should make it easier to get it right, but it also makes it easier to get it wrong.

There have been times when I felt lost when the Premier League line-ups drop. Too often, they’re comprised of small clusters of players who don’t feel fully complementary, and who narrow the number of coherent arguments we have towards a goal. Gone are the days of simply hoping to see some players and hoping not to see some others. Now, we’re scanning for compatibility.

Nail it, and we can win anything. Are we on our way to doing that?

👉 Faulty wiring

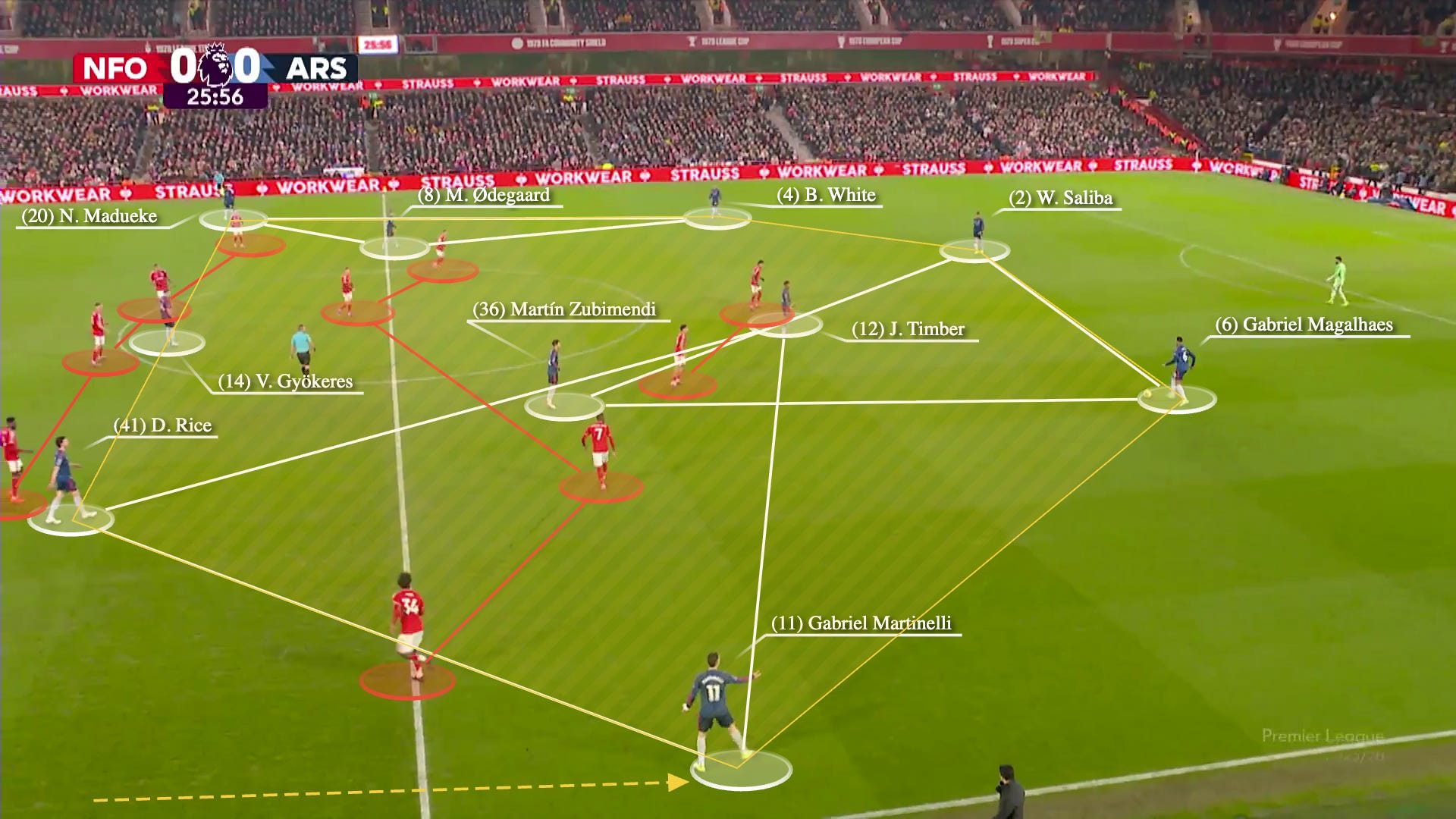

My criticisms were sharpest against Forest.

Arteta was not short on resources for that one. Aside from the XI, Arteta had Saka, Trossard, Merino, Jesus, Eze, and Havertz available at the very least. Still, we could see a series of issues from the lineup drop.

The right triangle had White, Ødegaard and Madueke. Pretty solid, though Ødegaard would be without his partner-in-crime, while facing the exact kind of matchup he struggles with the most: being a pocket player behind a physical DM like Elliot Anderson.

Without Merino or Havertz, there was no aerial outlet.

The middle had no coherent method for generating threat on its own.

The left didn’t either, and notably so. Facing Dycheball, that grouping consisted of Rice as a pinning player in the left half-space, Martinelli running at a fairly settled block, and Timber inverting into midfield, onto his wrong foot as a left-back. Who is dribbling to unsettle this block? Who is providing wide help? Who is providing the killer ball?

With Timber staying low as a pivot, and Rice high on the left, this also constrains Zubimendi’s movement. He’s not going to join the high attack as much because he has less rotational coverage.

The front-three had two off-ball runners and Madueke.

The intent to “overload to isolate” is clear. But what if that doesn’t work out? Where are the reroutes, the parallel paths, the redundancies? What would an attack on the left look like?

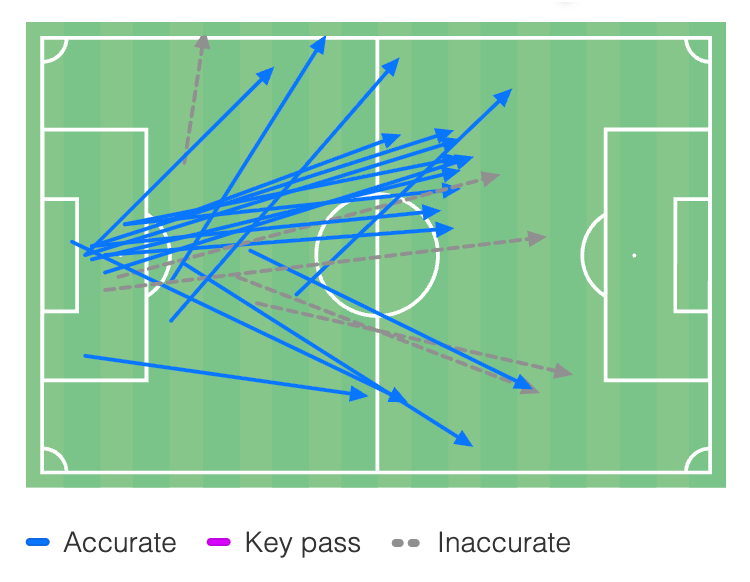

In practice, it often looked like this.

It was a little too similar to Bournemouth, when the “finishers” started the game, but couldn’t get going on the left.

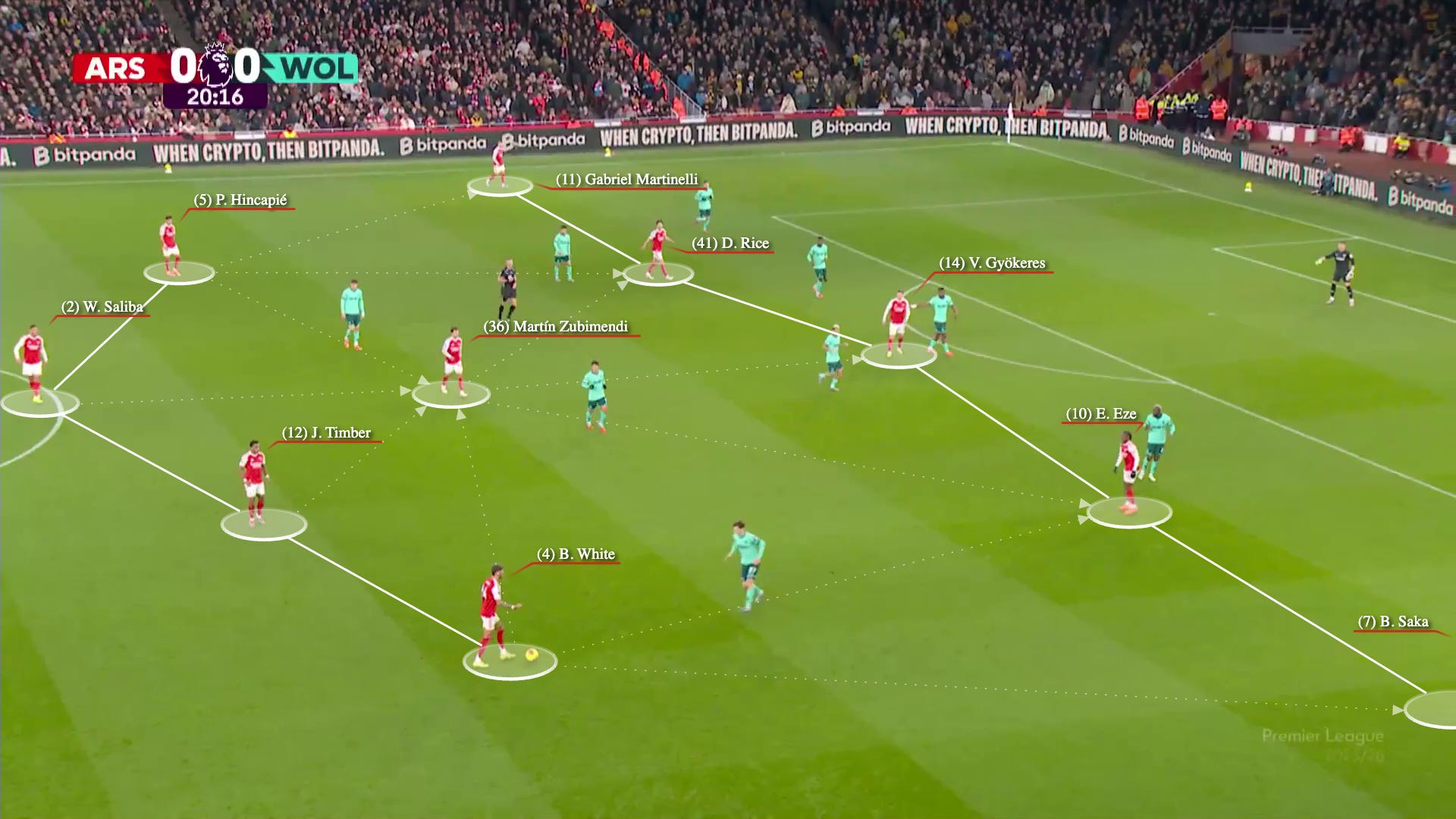

Against Wolves, who sit deepest in the league and have won one (1) time, Arteta’s frontline included two in-behind threats (Gyökeres and Martinelli), as well as Rice in the pinning LCM role.

All of these may be explainable in isolation, but collectively, they paint a pattern.

The Forest game ended 0-0, the second scoreless draw in a row. A contrarian may point to some missed chances by Martinelli and Gyökeres, but one was on a second-phase after a set piece, and another was after a Forest error. Neither, in other words, was due to structural superiorities in open play, and the first half finished with 0.35 open play xG and 0 shots on target. More importantly: it just felt like players were fighting to overcome the setup.

The floor has remained higher than that of other teams. But there is no doubt that the attacking ceiling can be raised.

👉 What would “better” look like?

It’s oversimplified, but in any outside trio, I’d like to see a few adjacent profiles:

(Below) An orchestrator: somebody who can dictate play and pick apart the opponent shape with passes.

(Beside) A dribbler: somebody who can drive at opponents and collapse the shape, starting a cascading effect.

(Beyond) A runner: somebody who can interpret space and pull it apart: “decompacting” the shape horizontally, diagonally, or vertically.

Ideally, a player has the flexibility to play multiple roles based on rotations.

The first example that comes to mind of such a trio is Trent Alexander-Arnold, Mo Salah, and Jordan Henderson. Henderson would always try to peel a yard or two of space for his colleagues, and then the group would pounce on the advantage with their unique talents. If they were all orchestrators, or all dribblers, or all runners, it wouldn’t have worked nearly as well.

Another shining example? For a year or two, one could argue that the most productive attacking trio in the world was Saka, White, and Ødegaard. At their physical best, Ødegaard could orchestrate from deeper positions (and is actually a great decoy runner on the inside), White could orchestrate or run, and Saka could generate paranoia in all three points of the triangle, but especially on the dribble. It left defenders with nothing but bad choices. So much was happening in blindspots.

With some help from Havertz, we saw their complementary characteristics pay dividends in that early goal against Bayern, in which Ødegaard orchestrated from deep, Saka generated disorder with a dribble, Havertz won a recovery, White picked out a perfect pass, and Saka scored for the opener.

This isn’t the most explosive running triangle imaginable. But White was often near the league lead in overlaps performed, and their ability to consistently perform all three roles at a given time (orchestrating, dribbling, running) made them a tough mark.

👉 How to improve

Arsenal can show more of this thrust with available resources.

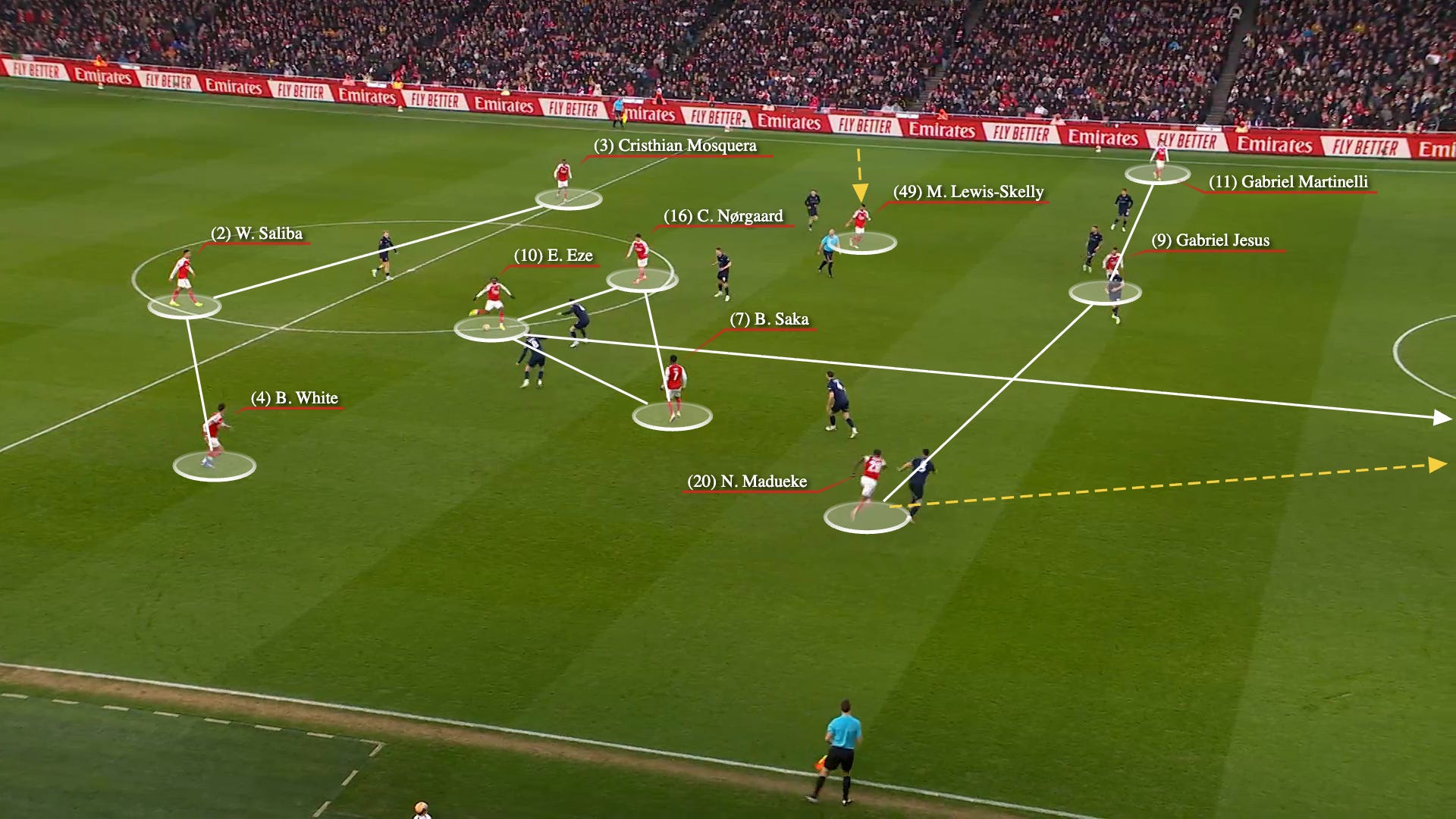

An easy, if not indicative, example for me to provide would be against Kairat. I know, I know: competition level. But in the spirit of being horses for courses, this was the perfect gameplan.

Why?

Back triangle: There were two ball-playing CBs against an overmatched opponent, and a more stationary #6 to anchor their movements.

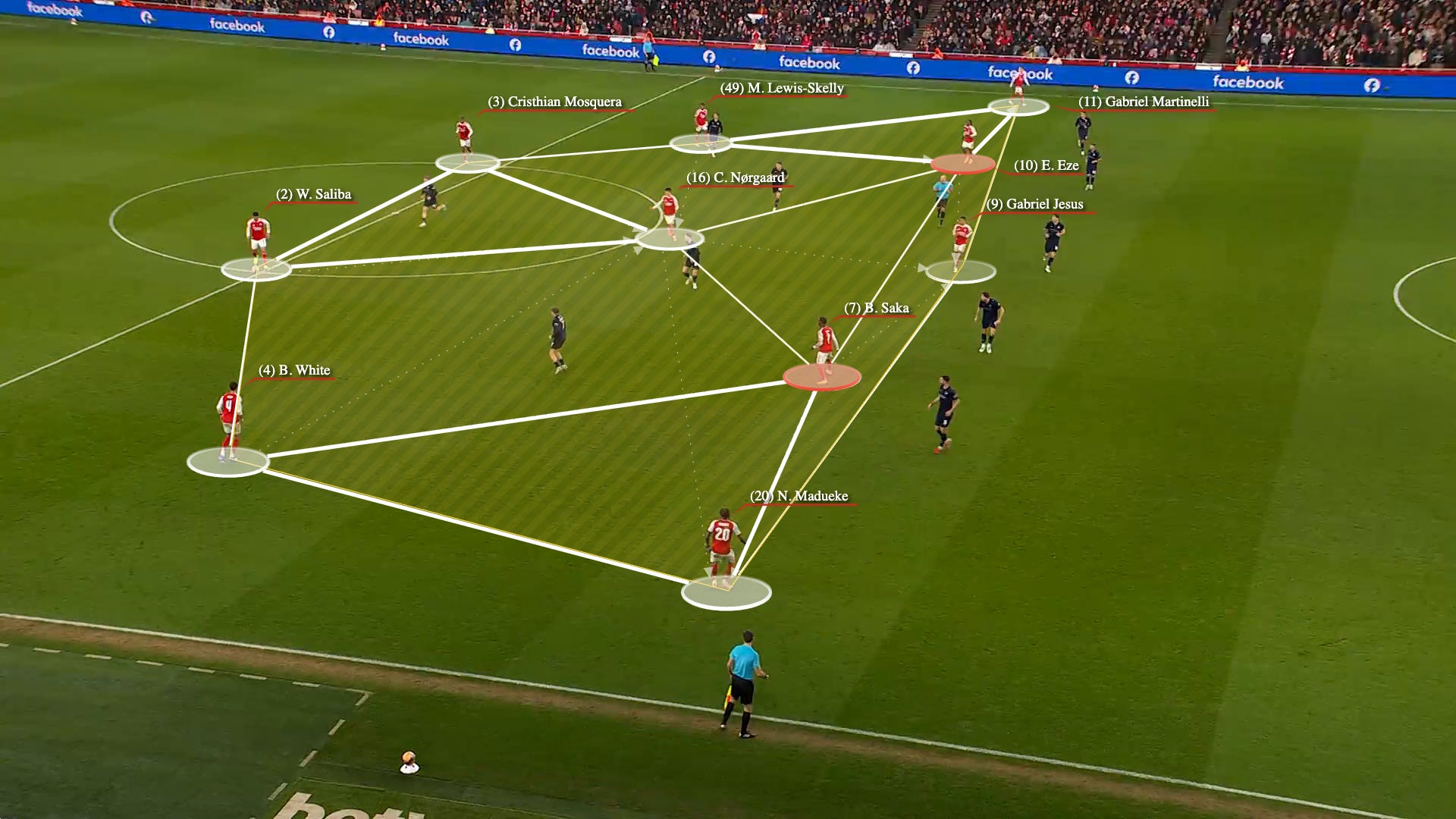

Left triangle: There is an orchestrator (Lewis-Skelly), a dribbler/playmaker (Eze), and a runner (Martinelli).

Right triangle: There is an orchestrator (White), a dribbler (Madueke), and a runner (Havertz).

There’s also a good argument for central combination play, with a tangible threat in both pockets. Gyökeres can also float and create diamonds at will.

That leads to a natural sense of motion and energy, leading to chances like this.

Those links reappeared against Wigan, though perhaps by happenstance. Calafiori was originally slated to start, with Saka set to join from the bench, Lewis-Skelly likely from LCM, and Eze likely to play at RCM. With Calafiori going off in warm-ups, we got this instead:

I think we all would have liked to have seen Lewis-Skelly in midfield, but I’m also glad we didn’t see Eze out of the LCM.

This setup led to four goals in thirty minutes.

We’ve seen a laundry list of combinations over this period. I believe there can be learnings from any game, no matter the opponent, so long as you know what you’re looking for.

(And for my own sake, I’ll also mention: nearly all of this newsletter was written before Wigan, back when Eze stocks were at a low. I was buying those stocks.)

👉 On the left

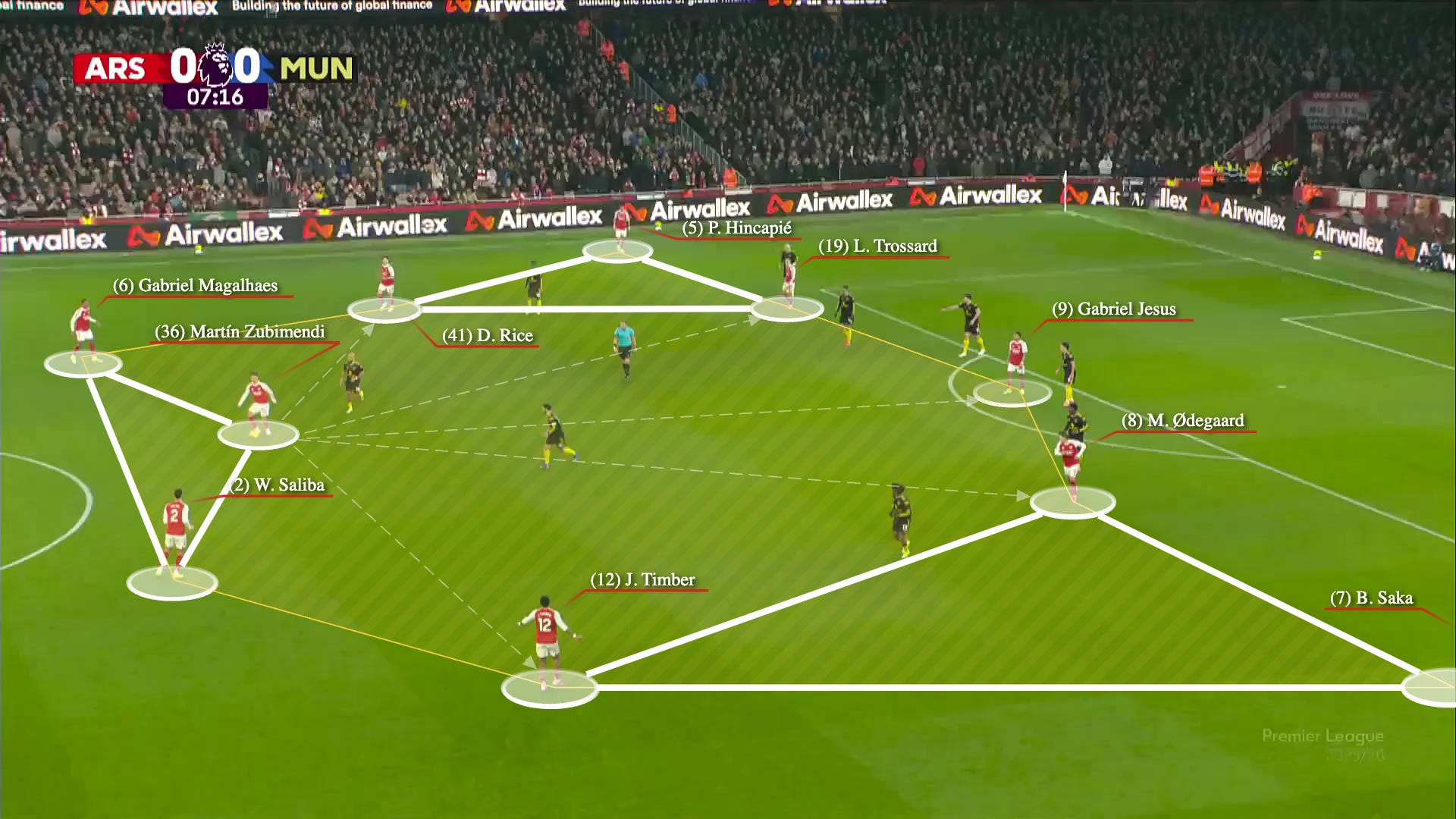

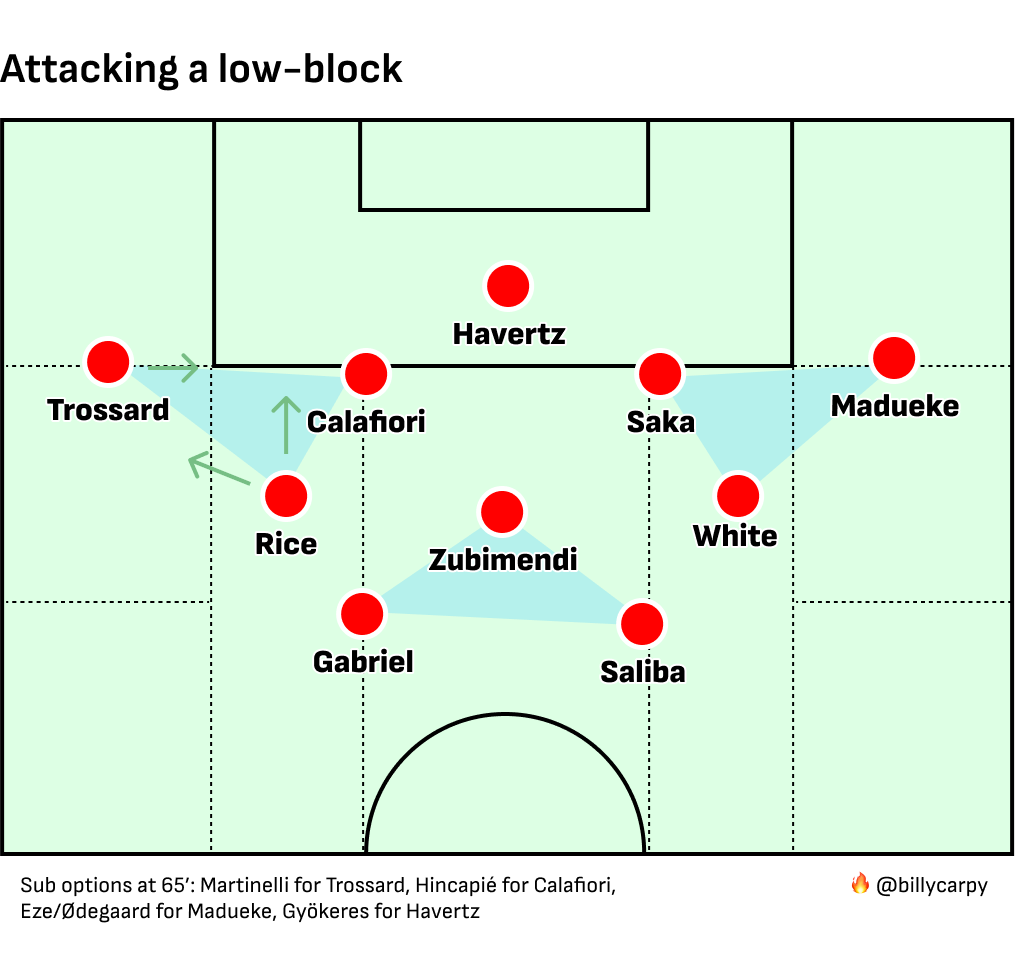

With Calafiori returning from injury, and Trossard having a great year, Arteta has been turning to this left triangle of late: Hincapié, Rice, Trossard.

Hincapié is useful in such games because he can make full-pitch sprints to run down the opposing winger, and has clean receptions deep. He provides motion and crosses in the attacking third, but is still gaining refinement about what to do and when. Combine that with Trossard’s ability to pick away at settled blocks, and Rice’s unadulterated Rice-ness, and it’s a fairly appealing setup.

This trio, in so many words, has been … pretty good. We saw much of the attack started over here at Brentford, with decent activity and performances by Trossard and Hincapié.

The reason this has been pretty good is because of the profiles. While you’d historically want him to be closer to goal, Trossard has been most useful as a wide playmaker this year, chalking up his boots in deeper areas while feeding runners in front of him with little manipulative passes.

But there is a limit to the ceiling of this setup. I laid out my ideal profiles in a wide trio, which you can take or leave: an orchestrator, a runner, and a dribbler. Trossard has been pulling the strings, and Hincapié has been a-running, but there isn’t a block-moving dribbling threat over there. Calafiori often fills that gap, Trossard does fine, but it’s still not at the level of a Saka, Madueke, or Eze.

That little gap is also why the left side’s best moments often involve somebody like Havertz or Ødegaard sliding over for an overload.

In more pressy games, we can see the value of some different profiles. We can see how good this feels to the plain eye: Eze and Rice have switched positions, Eze drops to receive, which frees up room for Martinelli to carry, and then Hincapié comes barrelling along with an overlap. Even if there aren’t numbers in the middle, this is how you like to arrive in the final third.

In a fast-forwarded version, in an easier matchup, we can see those three profiles I like: an orchestrator (Merino 🥲), a dribbler (Eze), and a runner (Martinelli). It leaves wide CBs and FBs with very difficult decisions.

In more open game states, it can flow like this.

My takeaways?

Things to dial down:

Retire Timber at LB unless it’s an emergency, or the game plan requires him to shut down a Yamal-type right winger.

We should also try to keep Rice out of the “pinning” LCM role as best as we can. Have him facing play, running, and arriving late to shoot.

Don’t start Martinelli against low blocks unless he’s paired with somebody who can attract attention in the half-space and release him.

Don’t start Eze as an outside, in-behind LW against vertically compact mid-blocks like Villa. That start was basically out of necessity because of injuries elsewhere, and there was a reason he struggled.

Eze on the inside of Trossard might work in certain tight-space games, but they’re not the most complementary in terms of off-ball dragging runs.

Things to dial up:

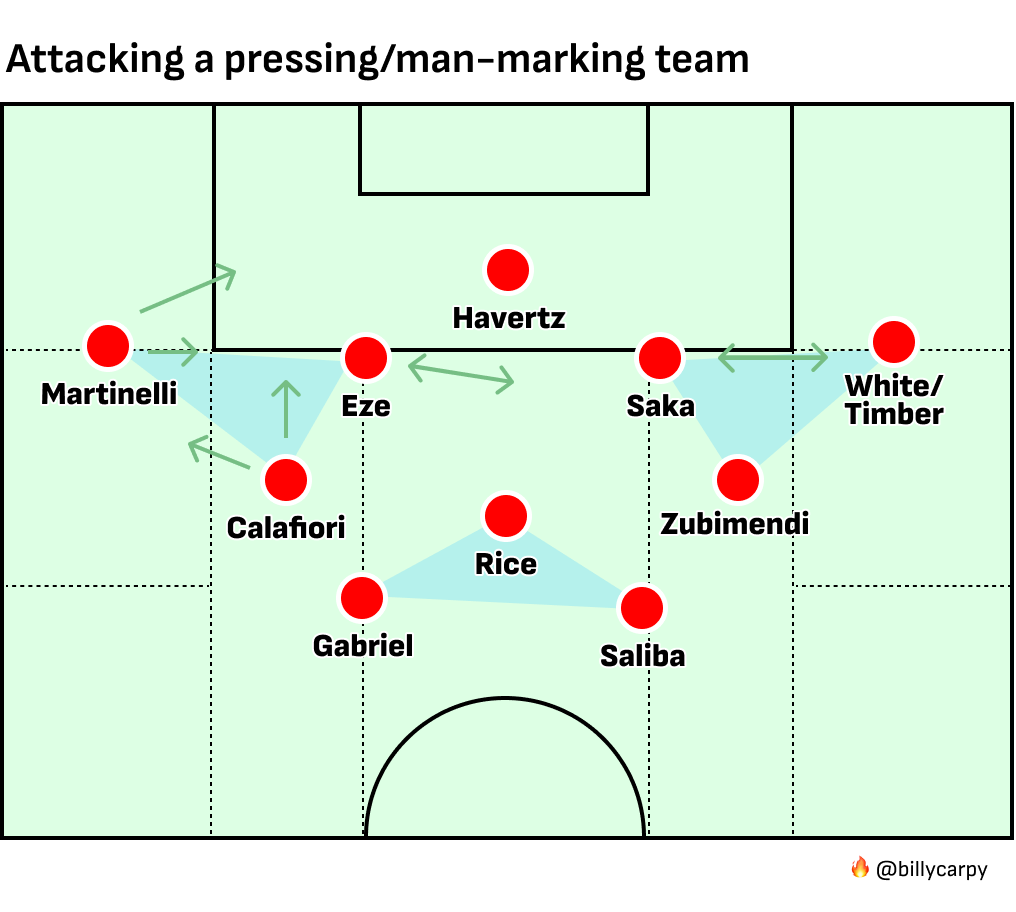

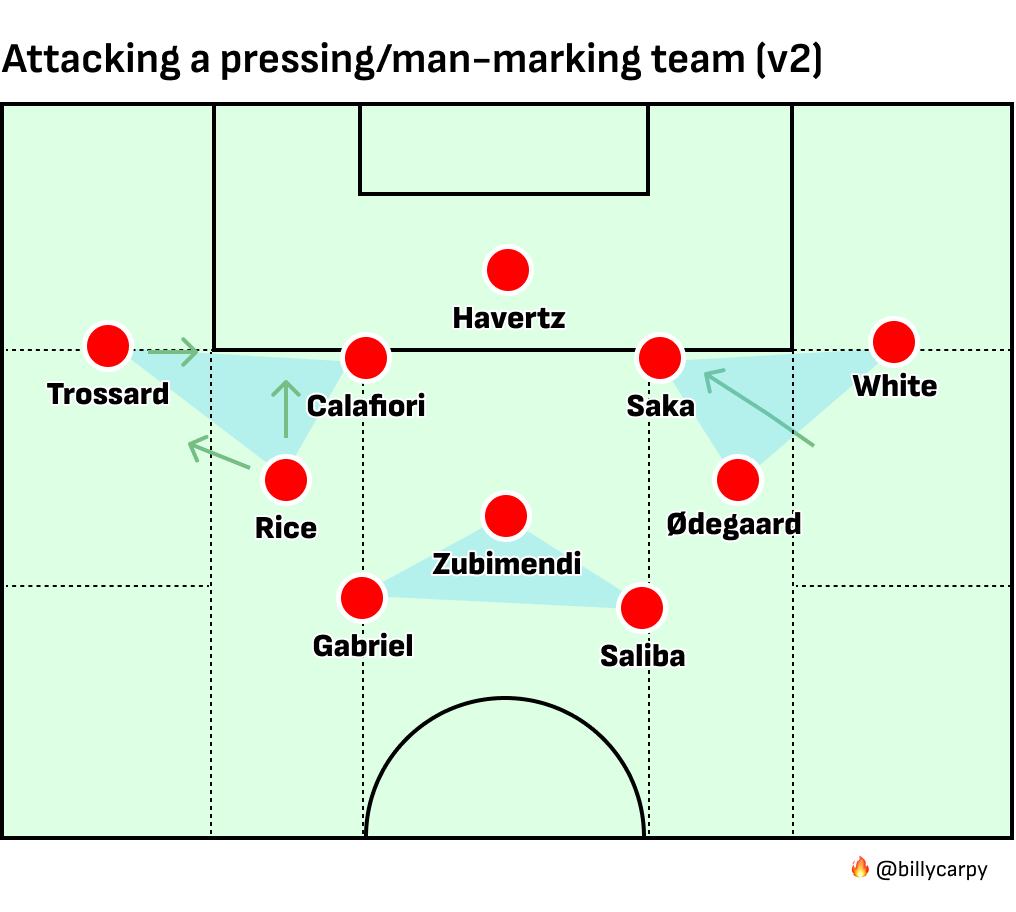

Put the pedal down on the Eze + Martinelli connection together on the left, particularly in man-marking or high-press games (often in the Champions League).

Trossard (LW) / Rice (LCM) / Calafiori (LB) generally works as a sub-unit, especially in first halves against stubborn blocks.

Trossard (LW) / Rice (LCM) / Hincapié (LB) is solid, but has minor limitations. Specifically, it’s a bit short on dribbling. It’s good to have somebody like Jesus at striker who can help out.

Martinelli (LW) / Eze (LCM) / Lewis-Skelly (LB) has a high degree of natural compatibility. There’s dribbling, orchestration, line-cutters, in-behind, wide threat, central threat, everything you need. Also, importantly: I love it.

Eze (inverted LW) / Rice (LCM) / Hincapié (LB) also looks extremely promising in terms of interlocking profiles. It also gives Eze a lot of defensive cover.

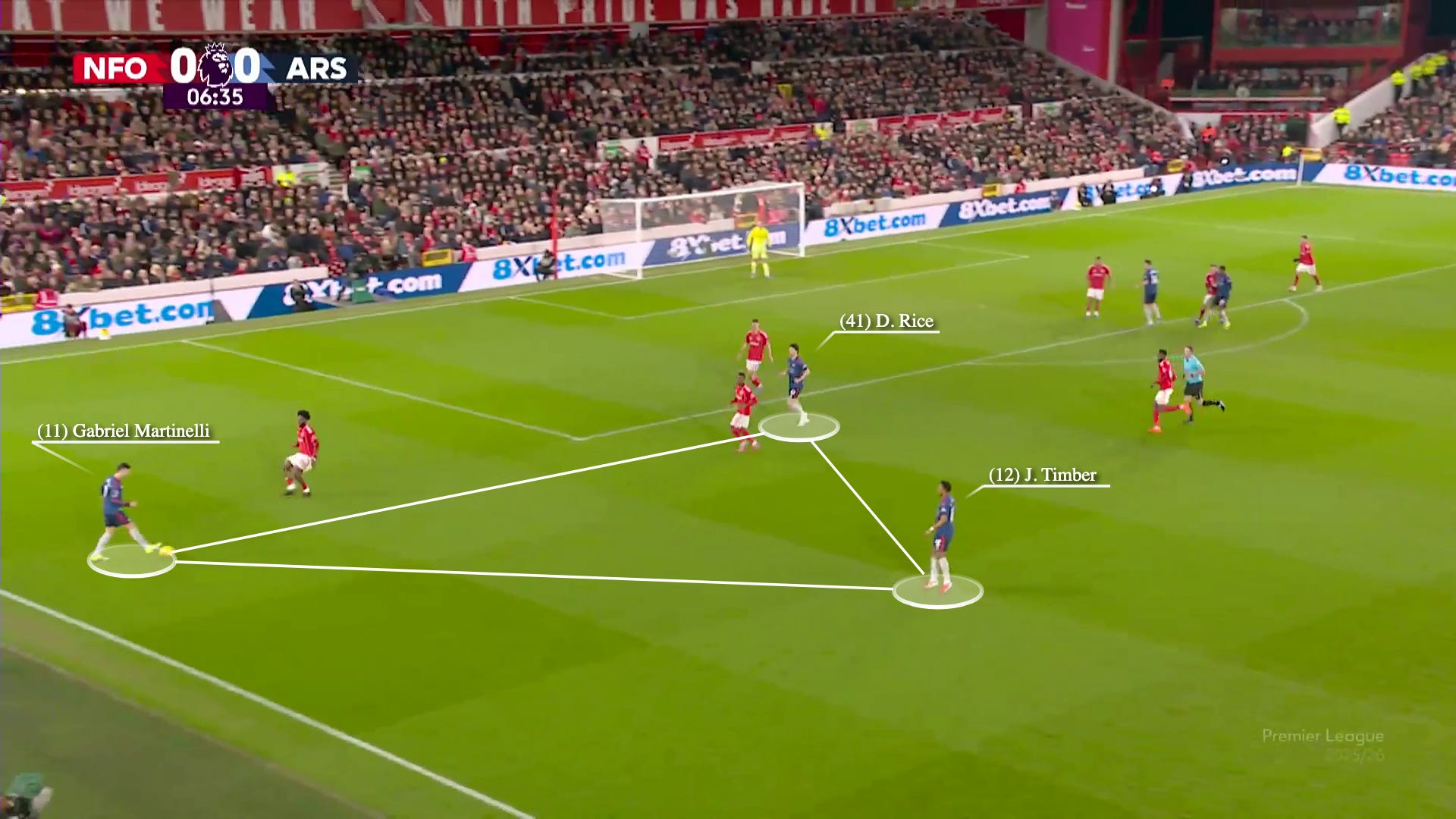

👉 In the middle

I have a simpleton’s mindset toward the question of central interplay. There’s a two-step process:

Use players who are good at combining in the middle.

Make sure there’s more than one of them actually standing there.

We’ll see situations like this, and wonder why the ball isn’t delivered centrally, and wonder why players float out of games.

If the central player gets it, who are they supposed to pass it to?

There are solutions. Against Leeds, the late Jesus goal can be easily explained. For one: Calafiori, Ødegaard, and Jesus can happily do this kind of thing; they have the requisite skill. For another, game-state.

The game had loosened up, so they were empowered to do this kind of thing.

At Inter, it was clear that the plan was to swarm them as much as possible. The pressing was turned up to the hilt, and players were driving and combining centrally from the first whistle.

Why did that work? The players and the positioning. Eze, Jesus, Merino, Lewis-Skelly, and others collapsed the middle, instead of the flanks, and showed the kind of rondo-like combinations they can make in the middle if given the chance. It was a critical mass of central combiners.

Takeaways?

Simple: we need numbers. Install better profiles in the middle places by default. Stack two or three players who can combine and rotate, not just one.

👉 On the right

The right, previously so settled, is also under a period of experimentation.

At times, the old dogs have been up to their old tricks.

But there has been a lot of rotation, too. That is, except Jurriën David Norman Timber. The right-back has played the second-most minutes of any outfield player for Arsenal this year, after Zubimendi. He’s made 36 appearances in total.

Timber and Madueke have done rather well as a duo, as Timber is likely to be driving to the half-space, while Madueke is so comfortable starting in wide areas.

But they both have a final-third chaos streak, which can sometimes compound.

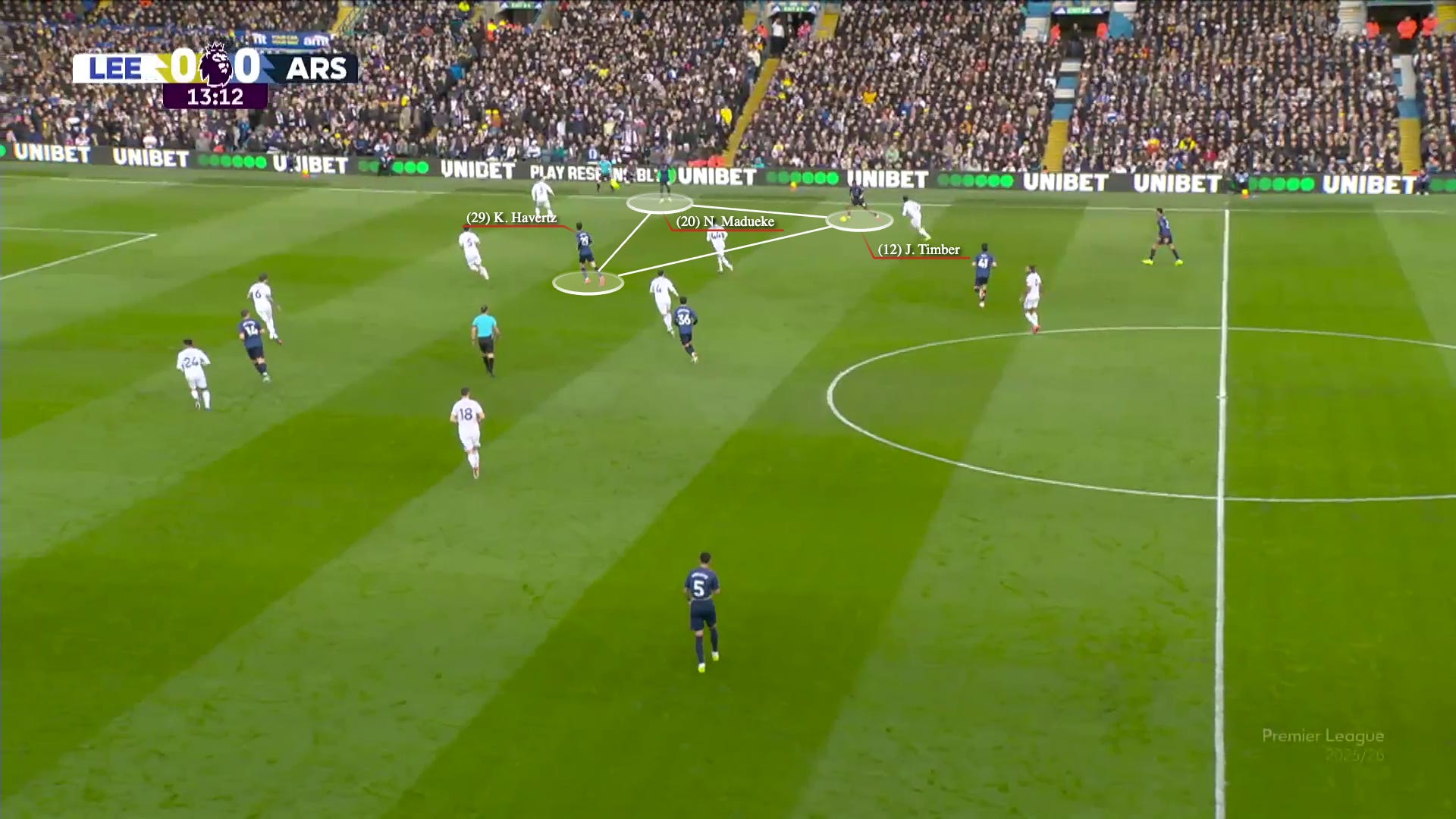

We’ve also seen Havertz join that triangle, though it doesn’t feel appropriate to call him the RCM, outside of his pressing responsibilities. He is, basically, a central combiner and an in-behind threat in this role. Against Leeds, for example, he provided one pass to Madueke and exactly zero (0) to Timber.

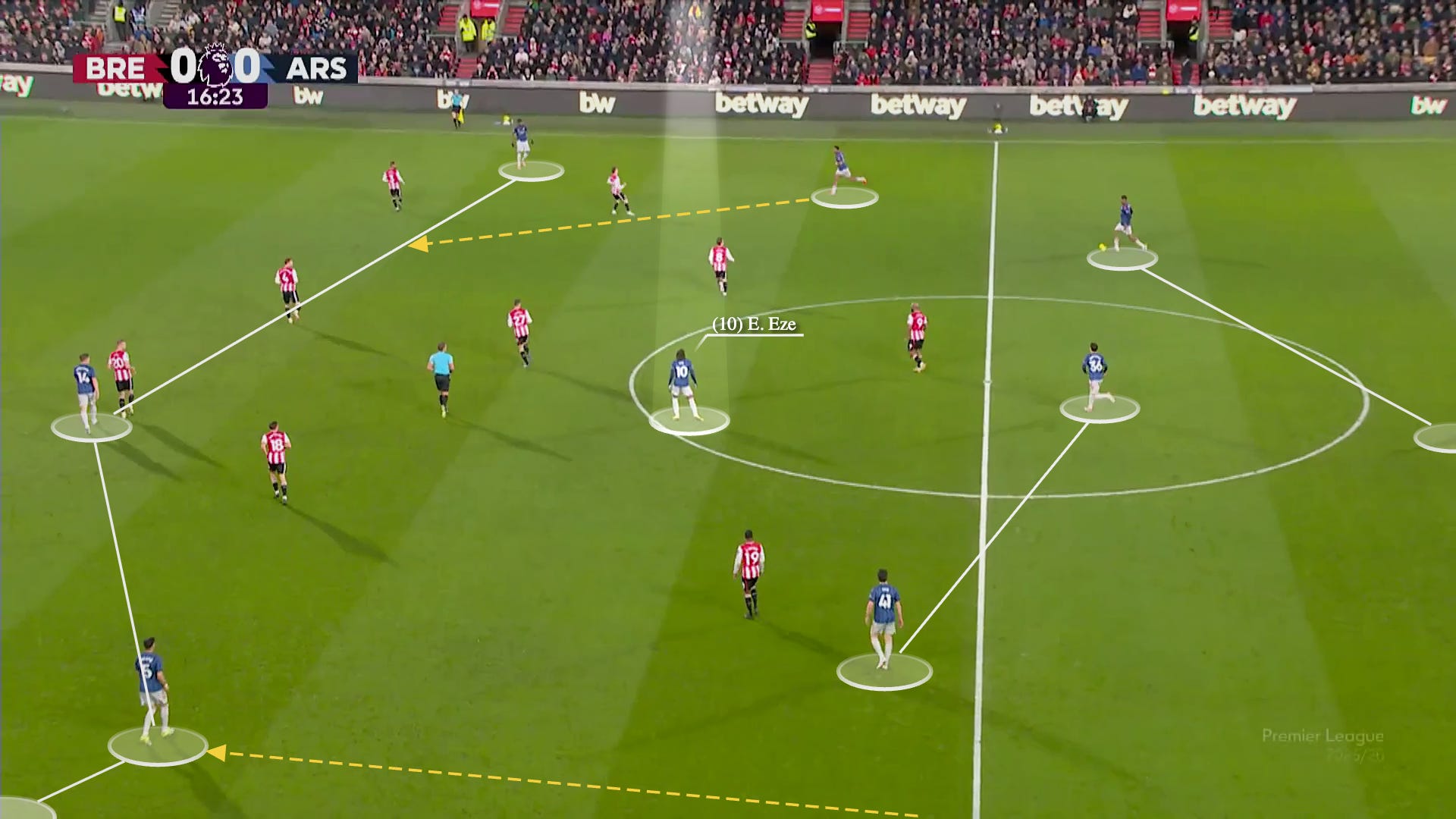

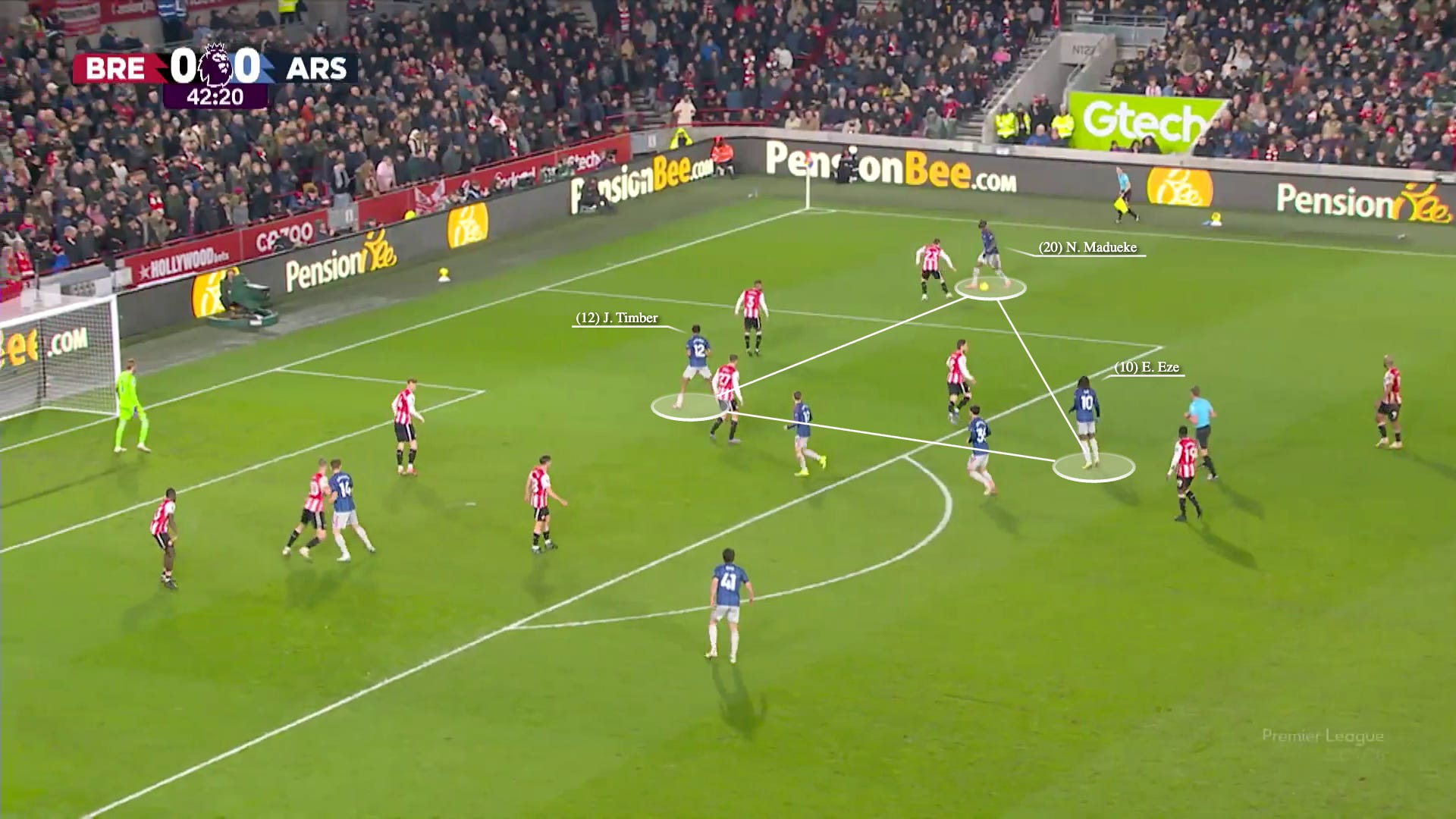

Eze’s role against Brentford was decidedly off-ball. In a half, Madueke passed to him once, and Timber passed to him once. Other than that, he was trying to float in the right-middle areas, pulling defenders around, but never really getting on the ball himself.

Against Wigan, we saw something fun and long-awaited: Saka as a roaming, pocket #10.

But it’s worthwhile to take a step back.

The orchestrator is your half-space rhythm guy who can take pressure and rip apart the shape with a pass. The dribbler is the one who actually bends the block and forces the fullback to commit. The runner is the third-man threat who can cause awkward leans and jumps, whether that’s via underlap, a channel sprint, or a box arrival. When you have three guys all wanting it to feet, or three guys all wanting to combine short, the triangle turns into a traffic jam.

In an attacking sense, the ideal world is probably still White/Ødegaard/Saka, for the obvious and amply-proven reasons. The current issue is related to physical levels and availability. All three are battling fitness concerns. Ødegaard is currently having trouble sustaining his physical levels for long. He’ll have bursts of looking like his old self, but then the energy level dips, then he’ll avoid contact. He’ll even stay off his usual pressing and build-up best, struggling to feel pressure.

As long as that’s the case, it’s where I’d make the case for Zubimendi to play more in the RCM “orchestrator” role. He can still generate tempo deep, but also do a simulacrum of Ødegaard’s work as a final-third player, while dropping back into the double-pivot. He’s so good at interpreting and finding little pockets of space.

This results in the balance of an Eze (LCM), Rice (6), Zubimendi (RCM) midfield.

If we need the RCM to be the runner instead, that’s Rice.

He is fully capable of being Steroid Jordan Henderson, giving you the third-man threat and box pressure. It’ll be best with White, who can play the deep provider role, but you can have Rice/Saka/Timber do all three points in a triangle; the actual deliveries into the box may lag a bit, and require assistance from Saliba and the #6.

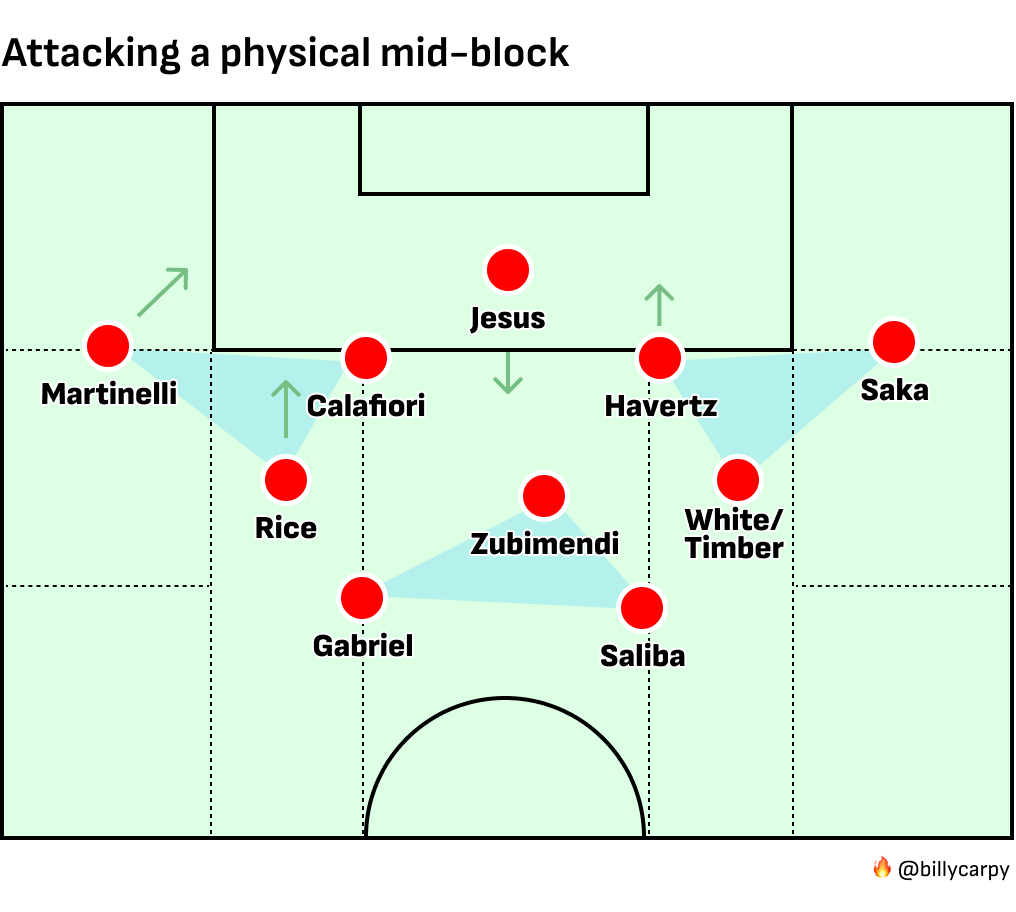

Havertz probably makes the most sense as an advanced midfielder when playing a vertically-compact midblock like Villa.

In those situations, it’s good to have a #9 to occupy centrally and do diagonal runs in-behind. It’s also good to stack big profiles to try and get a set-piece goal. The Havertz and Gyökeres combo can be used to destroy weaker opponents, or late in games, or perhaps against these higher mid-blocks, but I’m more measured otherwise. Havertz makes Gyökeres better because Havertz makes everybody better.

And I think Saka-at-RCM feels much more than a one-off.

While the Wigan lineup may feel like a vibes selection, there is nothing about a triangle of White/Madueke/Saka that feels naïve or matchup-dependent. It just works, and it works because Saka is good at everything. As Arteta said after the game:

“Well, he's more central, he's closer to the goal. It's a bit more difficult for the opponent to get his reference constantly. He can interchange positions with a wide player as well, and he’s so good at picking those spaces. When he’s there, he can really hurt you with the ball.”

The thing that was Wigan-specific was Eze playing as a low-8 who was double-pivoting in the defensive shape, which also helped the Havertz/Gyökeres duo against Kairat. That Eze job is going to be a tall ask against tougher sides.

Meanwhile, one thing we should really ramp up is the amount of Madueke give-and-goes. He requires such close marking in the widest of areas, and is really quick out of the block. This should be drawn up more.

And yeah: probably time to sunset Eze as a tethered RCM. He’s better used elsewhere.

He can still occasionally start there so long as he’s unhooked and free to move left, like he was against Chelsea, but otherwise, we just haven’t seen a lot of natural interchange from him on the right, and he struggles to get shots off unless he’s arriving left-to-right in zone-14. He’s played on the right a good amount, and none of his best moments of the year come from that pocket.

Some takeaways?

Get better, Martin Ødegaard and Benjamin White. If healthy, White should be playing more.

There’s no reason we shouldn’t see Saka in the RCM again, so long as Madueke is healthy and firing. That prospect has always been looming, but we finally have a right-winger who can take people on. Even better, Madueke looks best when starting super-wide, stretching the half-space. There’s a non-zero chance that this could be the preferred setup moving forward.

In the meantime: a Rice / Zubimendi / Eze midfield is also quite balanced. The issue is how we’ve been using them. We should seriously consider Rice and/or Zubimendi in the right midfield role. Zubimendi can replicate much of Ødegaard’s orchestration. As needed, Rice could play a more aggressive, Henderson-style advanced role, especially on underlaps.

Start Havertz every game he’s available, but predominantly at the #9. As an advanced midfielder, he’s most dangerous against physical mid-blocks, dropping centrally and then running in-behind. Diagonal runners are great to have in those games.

Martinelli, as a late-game right winger, is a lovely option. If chasing a goal, I’ll still also make my dumb case to throw him as an RWB, pushing Saka into the right-10, in addition to a Havertz or Ødegaard type at RCM.

While uniting all these factors, and while Ødegaard gets back to his best, this is the kind of all-purpose lineup that has a lot of balance, in-behind threat, playmaking, dribbling, and aerial threat.

Against a more Villa-style block, it can look like this.

And, of course, when the time is right, we can get back to some of the settled science.

These looks aren’t all-encompassing, and I have some others to show shortly.

But there are even more factors playing into selection.

👉 Creativity at the source

When thinking about balance on the right versus the left, one aspect goes underdiscussed: the source.

At left CB, we have someone who is quite good on the ball. He communicates and builds angles well, and can hit over-the-top passes with nice weight, but his first touch can sometimes be lively, and he isn’t a full “quarterback” style passer.

On the right, we have an alien.

This shit ain’t normal.

He can rotate into midfield, effectively play right-back, and carry the ball the length of the pitch like this, manufacturing an attack and delivering it centrally.

He can also log 100 touches comfortably, using feints to manipulate the opponent’s shape before blasting weighted long balls in behind.

He’s also effective when joining in high areas.

On the left, we see decidedly above-average play, but also a few too many long balls that are essentially clearances. It is fair to say that Saliba would try to muscle his way out of a situation like this to keep it on the ground.

Compared to Gabriel, Saliba attempts about 15 more passes per 90. He loses the ball less, is more accurate on long passes, and is roughly 10% more accurate on passes into the final third, while passing forward more often and more accurately.

This is not to critique Gabriel, whom I love. This is to acknowledge that, because the block is less likely to be unsettled from deep on the left, a quiet pressure is added to stack more creative forces on that side, but if anything, it’s usually been the opposite for Arsenal. The more creative CB typically gets more creative players in front of him. It’s time to look at tilting it the other way. I would also like to see a healthy Calafiori get a few more minutes at LCB.

When Mosquera slides in, and people say it helps them forget Saliba is out, I say: I still miss Saliba very much. I saw a recent thread of commenters ranking Arsenal’s best players, and must admit I was perplexed by some of it. I see no world in which Saliba could ever fall out of the top three. Everyone is entitled to their own opinions, and here’s mine: I’ve long held that Saka is Arsenal’s best player, but until he returns to his most productive form, it is a coin flip between Rice and Saliba. Rice gets the edge because of how the modern game is played, but Saliba is also a one-of-one, all-world talent, especially in his age bracket. We’re 15-4-1 when he plays at least 45 minutes. If anything, he is a victim of making things look too easy.

I think he has taken the belt from Van Dijk as the best centre-back in the world.

👉 Low blocks

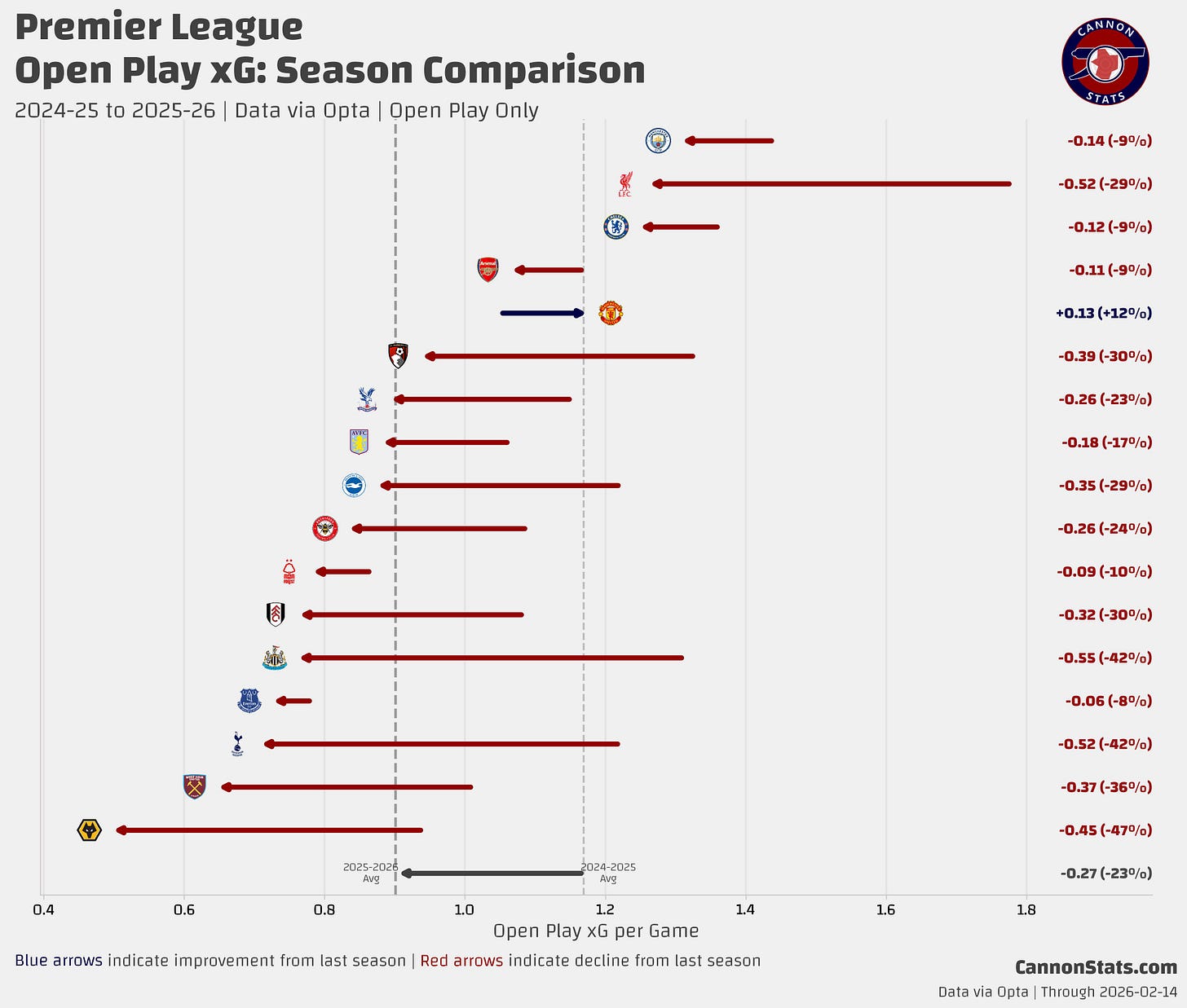

In this brilliant graphic from Scott Willis (go! subscribe!), we see that open play xG is down leaguewide.

This graphic, produced by PremierLeague.com after Matchweek 24, shows how goals are down, ball-in-play time is down, and late goals are up.

Anthony Gordon opined on the physicality of the Premier League.

“I think in the Champions League, teams are much more open. They all try and play. It’s less transitional. I think in the Premier League, it’s become more physical than I ever known it to be. It’s like a basketball game sometimes. It’s so relentless physically. There’s not much control. It’s just a running game. It’s sometimes about duels. Who wins duels, wins the game. Or moments. The Champions League is a bit more of an older style of game, a bit more football-based. Teams try and play proper football. In the Premier League, you see a lot more long throw-ins, set pieces, it’s become a lot slower and set-piece based, I would say.”

This steady climb is backed up by the data. As one study shows:

Running load demands (TD, HID, HSR, SprD, HID/min, HSR/min and SprD/min), total match minutes and congested minutes have increased over the last decade. The top six teams are exposed to more total and congested minutes than other teams.

In the Champions League group phase, five of the top eight teams were from the Premier League.

Arsenal both experience and create as much of this new “meta” as anybody.

Sam Dean tells us:

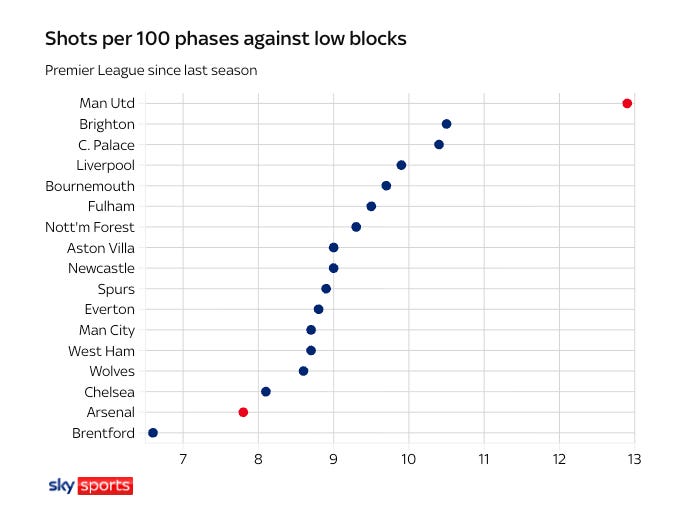

Over the last three seasons, Arsenal have statistically faced more “low blocks” than any other Premier League side. Their opponents simply do not dare to challenge them at their own game.

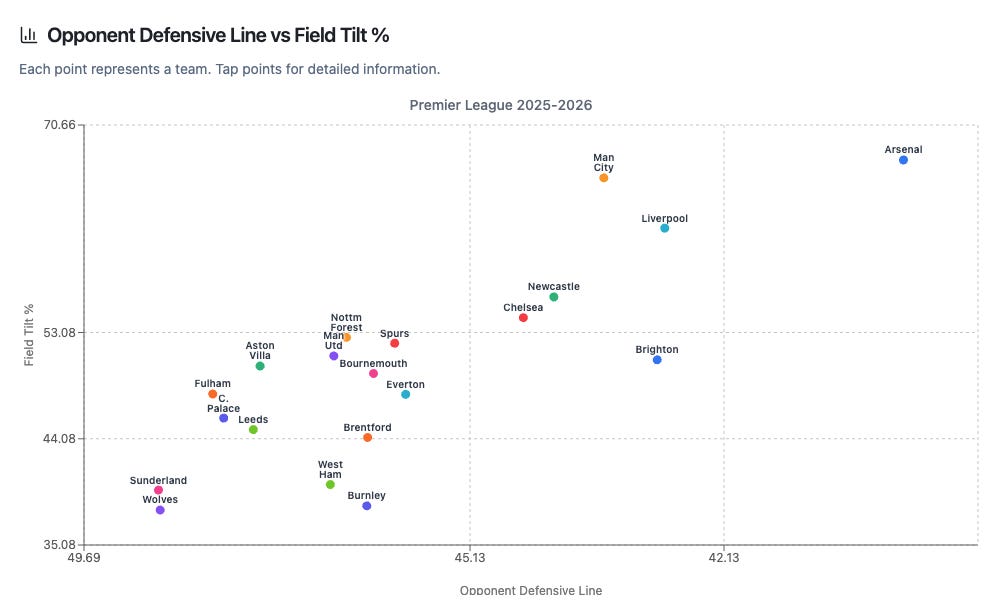

According to markstats.club, opponents make their defensive actions deeper against Arsenal than against any other side. Arsenal also lead the league in field tilt, which measures the percentage of ball possession in the respective final thirds.

Arsenal face the “highest” opponent PPDA, which stands for passes per defensive action. That metric quantifies how many passes an opponent allows before committing a defensive action in the opposing 60% of the pitch. A higher number means a more “relaxed” intensity.

In one of the more telling games in recent memory, Pep Guardiola brought out a full-strength squad to face Arsenal, scored quickly, and then parked the bus.

As Man City manager, it was Pep’s lowest possession ever, his highest long pass % ever, and his lowest passes per possession ever.

Pep’s no fool. There is good reason to defend Arsenal in this way.

For one, teams that try to go toe-to-toe in a man-marking, pressing-style game often come out second best.

We’ve seen this play out against Bayern, Inter, Chelsea, Leeds, and others this year.

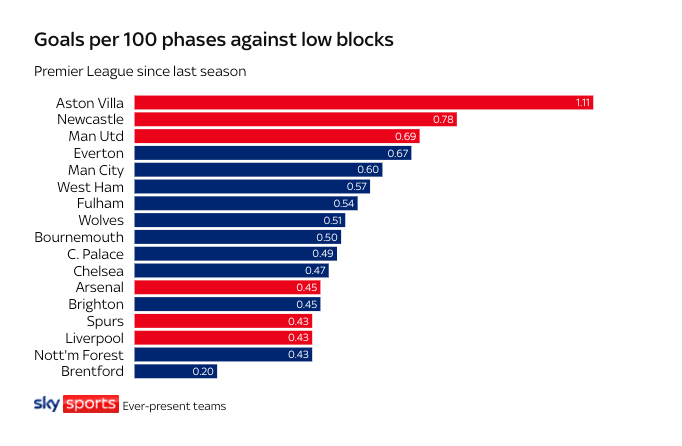

Now, there’s another reason they do this. Arsenal haven’t been very good at generating shots against low blocks.

We’re also down in 12th for goals in these situations.

One reason is the success rate of our full-back crossing to date:

Jurriën Timber: 5 for 41 (12.2%)

Riccardo Calafiori: 3 for 21 (14.3%)

Piero Hincapié: 3 for 18 (16.7%)

Ben White: 2 for 13 (15.4%)

Moving forward, starting against Wolves, I hope we never see a Forest-style setup again.

This is the kind of grouping that can be picked for these low-block games. Again, I’m looking at easing Ødegaard back so he can return to his physical levels. So here’s a tight-space triangle on the left, the Wigan triangle on the right, and Havertz floating and heading.

(With the caveat that Havertz is likely to be out for Wolves.)

In all, the effects of this marriage (Arsenal hope to push teams back, and teams are happy to oblige) should affect how we understand almost every aspect of the game. And it is a marriage: it’s easy to say Arsenal should attack more like Villa, and I think they should. But that strategy is not without its own risks. Remember who is still atop the table.

👉 Pressing as playmaker

From an analysis standpoint, any assessment of the attack also has to account for Arsenal’s pressing level at the time. When opponents sit deep and hoof, Arsenal lose the chance to press. And when Arteta tones the press down, whether due to personnel necessity or his penchant toward a conservative approach in first halves away from home, we stop winning the ball in advanced areas. Many of Arsenal’s best attacking moments start with the press, so if you ignore that context, it distorts how you may judge the open-play attack.

Arsenal’s eruption against Inter had much to do with suffocating their play high and creating chances as a result. Voilà, space.

Interestingly, Sunderland also opted to get out of their block and challenge Arsenal, both pressing in spurts and showing a willingness to play out from the back. They were so crisp and good, but yeah, they eventually paid for their ambition. Madueke showed his stellar closing speed and balance to win the ball before the Zubimendi blast that broke the seal.

But Arteta often dials things down in away games in the league. Perhaps in part because of the “new” front two in Gyökeres and Eze, the triggers were relaxed early against Brentford, resulting in rather unbothered build-up play from the Bees.

This is unlikely to result in those dangerous recoveries that turn into free-flowing attack.

It is no coincidence that the team looked most vibrant once the intent changed, Ødegaard came on, and the pressing was turned up.

At 7-4-2, Arsenal remain atop the “away” table with 25 points, so this strategy needn’t be binned. But it should probably be modulated.

👉 Pressure on build-up

It is, in other words, more difficult for Arsenal to create chaos via the press. But the opponent must still be moved around, and Arsenal has chosen to do this with frequent rotations, preferably in midfield.

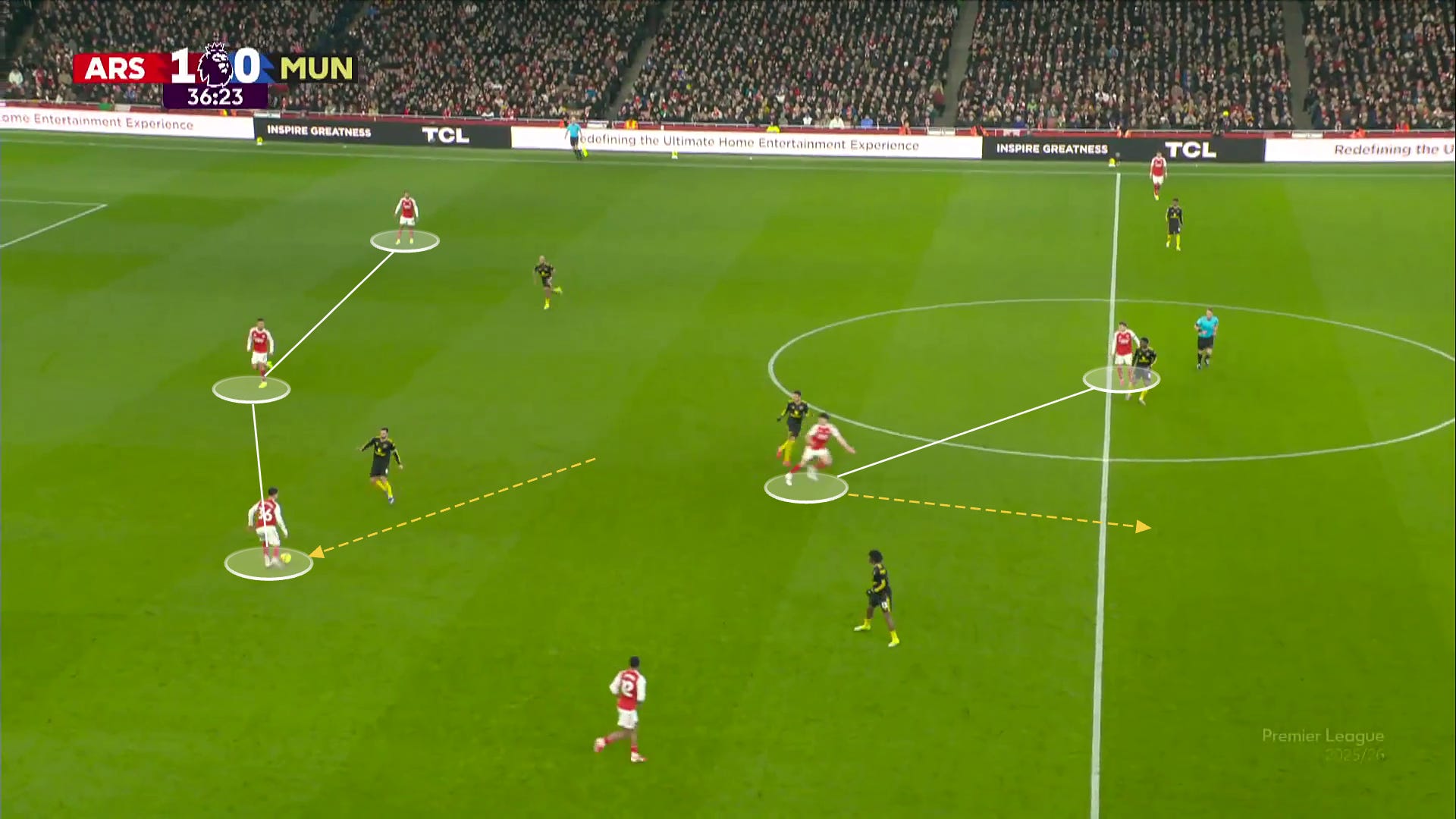

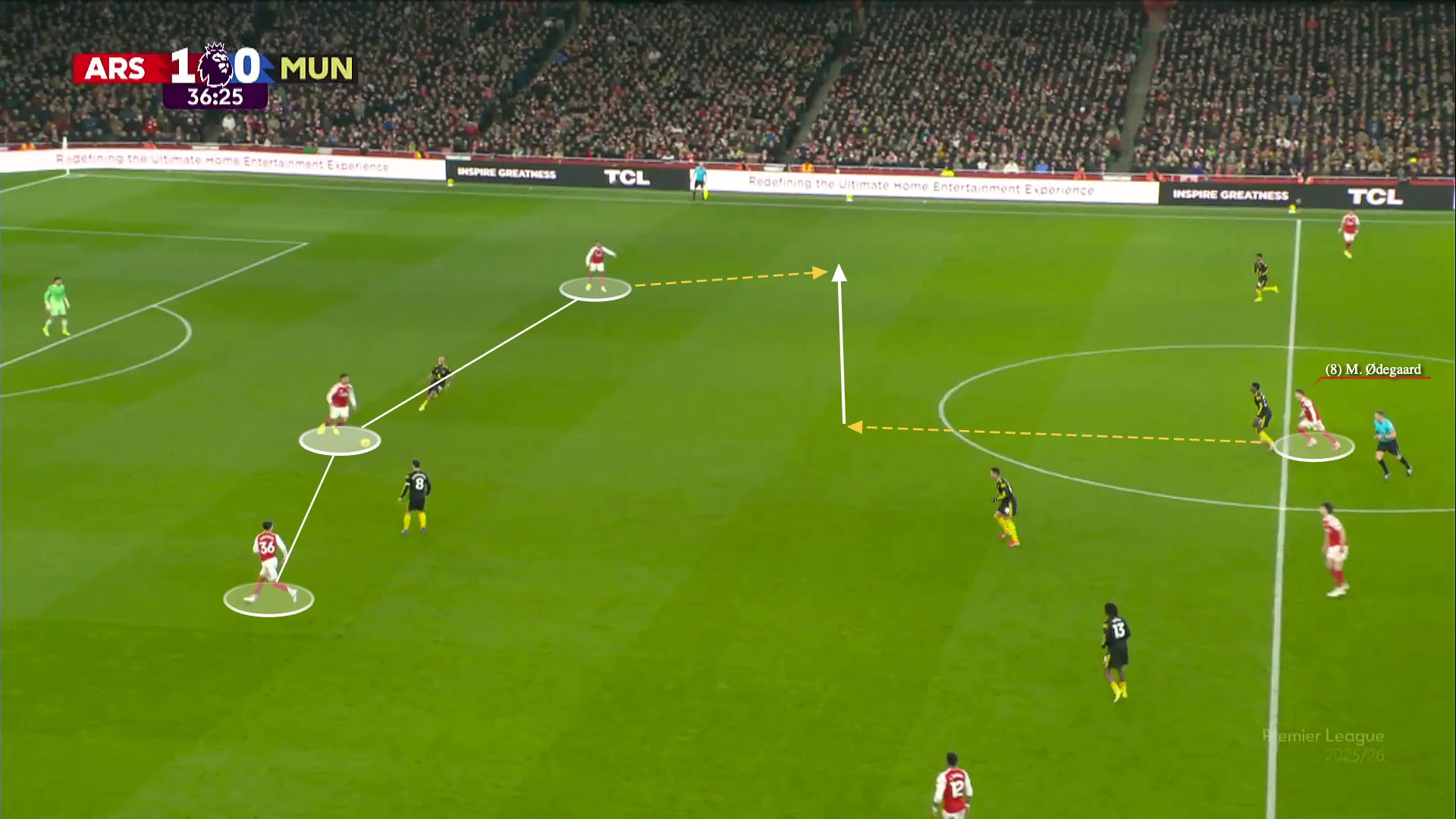

Against Man United, Ødegaard caught ire for carrying across the shape and then recycling it back to Gabriel.

But it’s clear that part of the plan was to exploit Mbeumo’s dual responsibilities. By baiting a jump, Hincapié can get free, then Maguire will have a difficult choice about whether to step out or not, disjointing the box.

Only 30 seconds later, in the same possession spell, Jesus dropped into the space, and they were able to trigger that Mbeumo jump. This freed up Hincapié, who delivered a cross across the box. Saka hit it to Ødegaard, who deflected a shot off Timber for the goal.

If you look back up, you’ll see Zubimendi as an RCB, Rice as a lone-6, and Ødegaard back up in his RCM spot. These fluid midfield rotations have been a hallmark of the team this season.

This model is not without its drawbacks. Just eight minutes later, in a position of little bother, Zubimendi dropped down to the RCB as Rice made a darting run forward, vacating the midfield. Zubimendi determined it wasn’t on and gave the ball back to Saliba.

In this fluid system, Saliba would rightfully assume that Ødegaard was going to drop into the space left by Rice and Zubimendi. But in the clearest sign that Ødegaard’s game is just a bit off, he’s late to do so.

Without an option, Saliba has to shield and recycle, and then Zubimendi just mishits it for the goal.

It’s easy to say we want the most fluid midfield imaginable, but with some rotations in that right-10 spot, there has been a feeling-out period as well.

Consider the lone #6 setup of the last few years, and then watch Zubimendi making a sprint down the left wing to generate a fourth goal against Villa. Jorginho, he is not.

Can we blame Lewis-Skelly, then, for thinking Zubimendi was going on another adventure?

Such is life with new players, new relationships forming, plenty of positional rotations, and injuries causing chopping-and-changing (particularly at RCM). The most comfortable thing to say is that the little miscommunications will go away as the team continues to build comfort. But I do often wonder if one of the double-pivot players should move more predictably, serving as a reference point for all others to rotate around. Zubimendi is yet to tally more than 79 passes in an Arsenal shirt.

But this shit is hard to turn down.

👉 Outlets

There is another element putting some pressure on build-up, empowering opponents to press more than they otherwise might: a lack of aerial outlets.

In an ideal world, you’re great at deep build-up, and you have a top outlet at #9, so your job is to simply… count. If the opponent has kept numbers back, you build out. If the opponent has pushed numbers forward, you hit it long.

With Merino out, Jesus understandably not quite as fighty in his aerials, and Havertz out for most of the season thus far, Arsenal have been much more resource-constrained on this front, and I think it’s a big reason you’ve seen some of the top-six results ebb when they’ve been so good in recent years.

This is partially why Inter (with Merino) looked like such a breezy build-up performance, and why there suddenly stopped being too many deep issues once Havertz returned to the lineup.

When you’re caught deep without somebody who can bring the ball down, your choice is to either take some real risks in a low position or clear it.

Gyökeres has greatly improved his pre-duel positioning, but his touch is still in the same place.

So, when Brentford come out to play at the Gtech, and we show some wobbliness deep…

…it turns to unstrategic hoofball, hitting it up to a starting front-four of Trossard, Eze, Madueke, and Gyökeres.

A target man is a warm blanket. You can build up with confidence knowing that if things get hairy, you’ve got a great option ahead. On the flipside, if you know a long-ball is likely to become a turnover, it can cause you to overthink and take unnecessary risks when deep.

This, again, underlines the importance of Kai. I’d also like to be more deliberate about balls delivered to Gyökeres. In the channel, instead of at his head, please. Martinelli offers some intriguing aerial potential, and I also wonder if it’d be worth training up a player like Madueke to bring the ball down as Semenyo can.

👉 Game-state

Game state shapes almost everything (G.S.S.A.E.). Mostly, it decides who has space and when. And it often makes the proceedings feel like a different sport depending on the situation.

That is a large part of the story of Arsenal this season:

In first halves, we are 12-10-4, eight points off Man City’s pace. We have only scored 18 goals in 26 first halves.

In second halves, we have been the best team in the league, tallying the most goals (32) and fewest conceded (12). Man City are seventh-best after the break.

You can see it in the recent away starts, which are often cagey, slower, and intentionally tuned down. Among those last five away first halves:

Brentford: 1 shot (0 on target)

Leeds: 2 shots (2 on target)

Forest: 7 shots (0 on target)

Bournemouth: 5 shots (1 on target)

Everton: 6 shots (1 on target)

That is fewer than one shot on target on average. Even Leeds, where we eventually blew it open, followed that pattern. Two first-half set pieces changed the game state, and then the reinforcements came on. The overall contours were not that different from Forest or Brentford, but our feeling from that game was, because we pulled the early lever.

Many will rue some recent lost leads, and that’s certainly been true in frustrating pockets. But it’s also worthwhile context that Arsenal are still managing game state better than last year: we dropped 21 points from winning positions then, and this year it is seven.

The attritional nature of matches looms above all; we see thinner squads like Newcastle and Crystal Palace falling by the wayside, exhausted and broken. For us, Sunderland was an extreme A/B test. At the Stadium of Light, we had no attacking subs to throw on (no Martinelli, Gyökeres, Ødegaard, Kai, Jesus, Madueke). We lost our legs late and coughed up the lead.

At home, we were the ones who knocked. Arteta had an embarrassment of riches to choose from, and the result was a Gyökeres brace, with Martinelli helping tilt the game.

And then you get the whiplash that comes with game-state. Right after that brace, Gyökeres gets held without a shot against Brentford. Martinelli, for his part, now has 11 goals on the season … but only one in the league.

Arteta has acknowledged these realities, but not necessarily gone all-in, also choosing lineups based on form and fitness. I would argue that it’s time to commit more forcefully to game-state: small-space players (Trossard, Calafiori, Jesus) when space is tight, and big-space players (Martinelli, Gyökeres, Hincapié) when the game opens up, a mixture when things are projected to be end-to-end. That feels like a repeatable method to win matches in this league, as it is right now.

👉 Long shots

In my 23/24 post-mortem, I outlined the things I hoped would improve for the Arsenal, which still feel too familiar:

Improve Plan B through the left

Increase risk tolerance in the middle

Boost team speed

Add ball-striking

A few more big passes

On a squad level, we’ve made upgrades across the board, but on a tactics, fitness, and selection level, we’re still a work in progress.

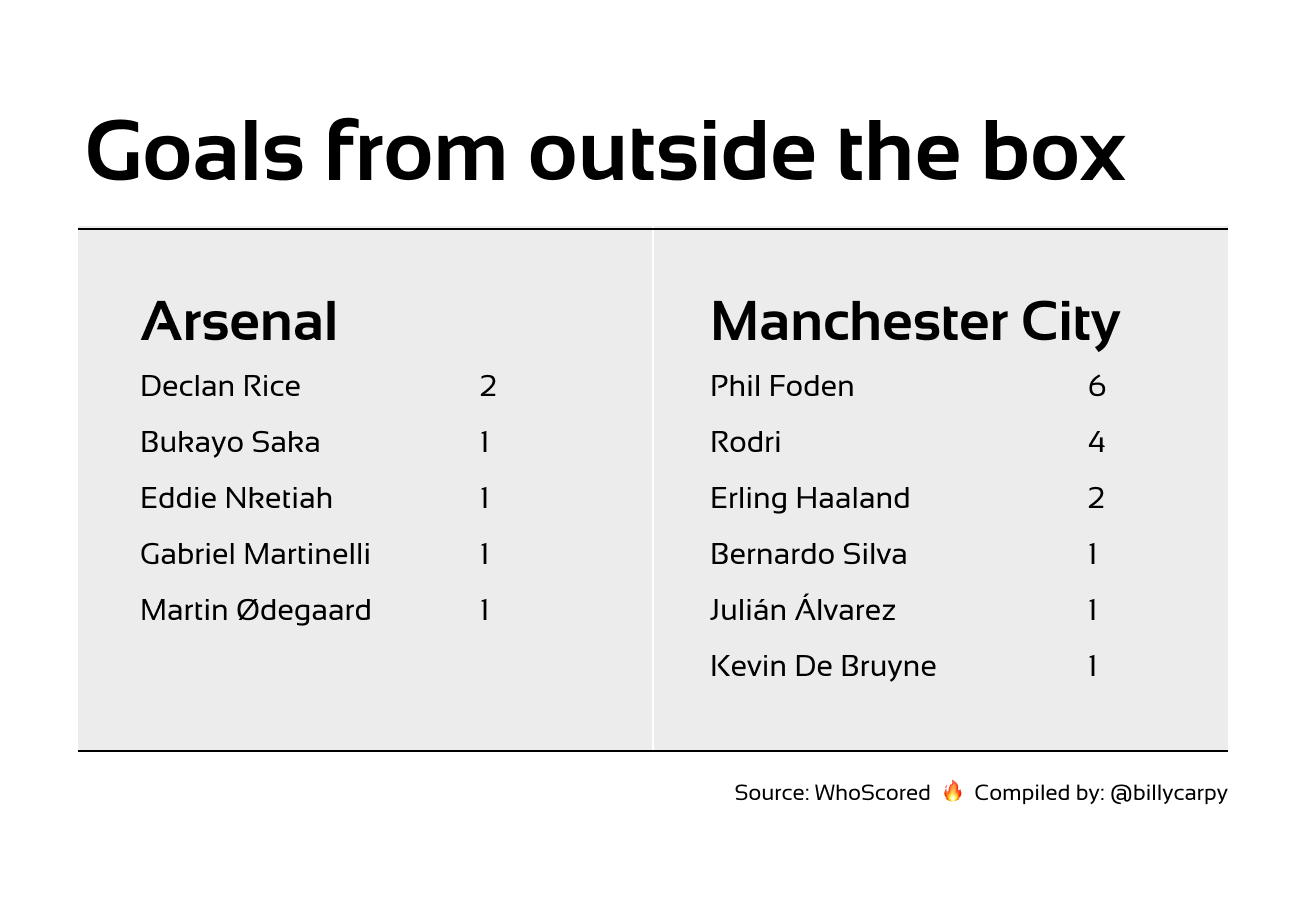

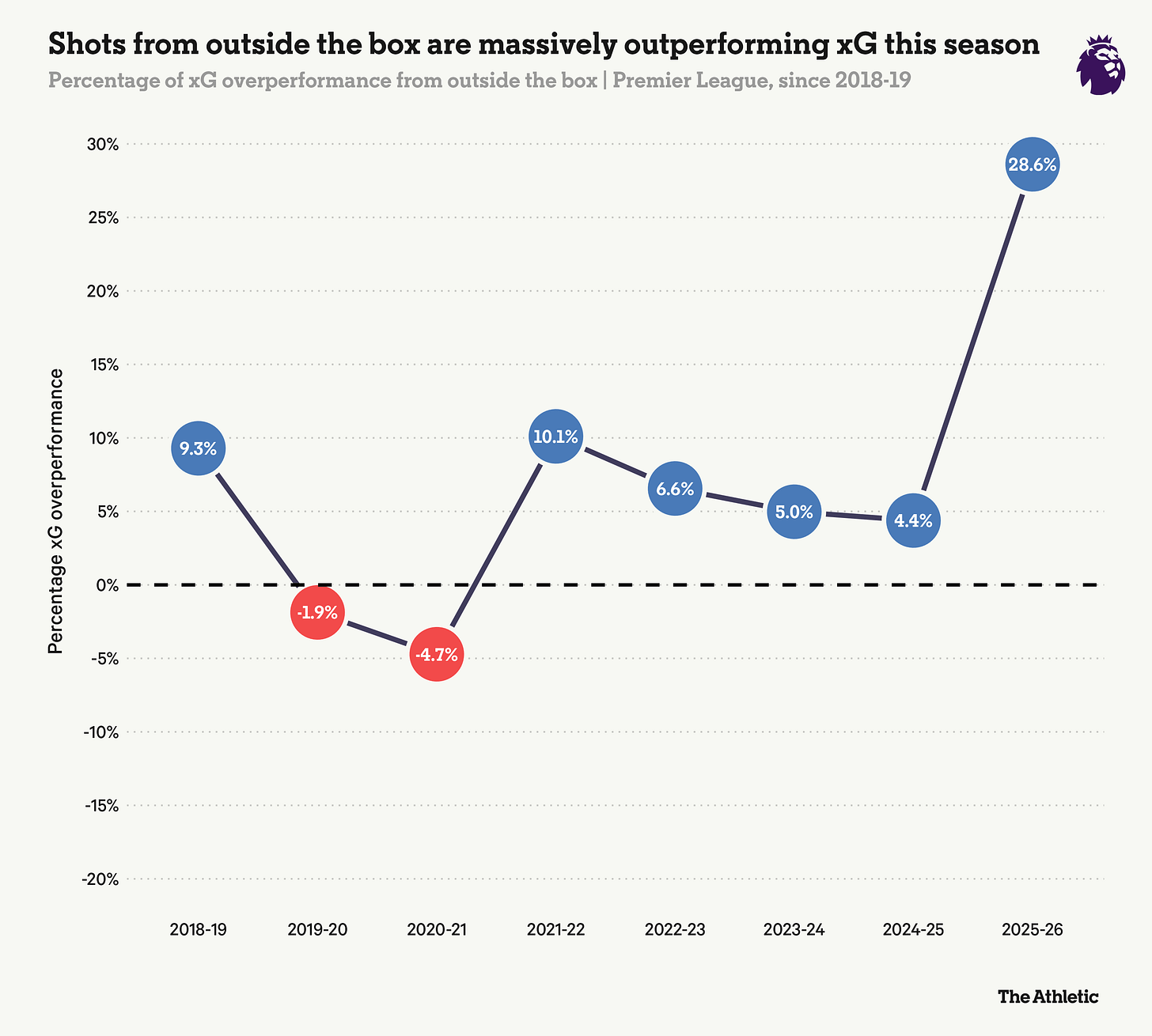

That said, one of the starkest lessons from that late-season City run was that they bested us 15-6 on goals from outside the box, which bailed them out of so many games they may have dropped points in. It was the difference.

So far, we’ve already bested our total from that year. Arsenal have scored 8 out-of-box goals in the league, and 12 total.

In league: Trossard (2), Zubimendi (2), Rice (1), Jesus (1), Ødegaard (1), Madueke (1).

As I wrote that down, I tried to recall Madueke’s out-of-box blast, but then remembered that it was against Brugge in the Champions League. Then it hit me: scoring from a corner kick is, indeed, scoring from outside the box.

These long blasts were clearly scripted against Sunderland. Rice gave a warning shot at 30’.

Before Zubimendi sounded an echo ten minutes later.

I drew that one out to call attention to the occupation of the box. Arsenal put maximum bodies forward to flatten the Sunderland shape, which opened up the desired space. As Arteta said:

“Again, it’s a situation that you get with time and space. If the space is not in one place, it will be somewhere else. But yeah, as well, there were three really good shots, and Zubi’s is a special one as well. He’s contributing now to the team in a way that probably we didn’t expect that much, but he really has an intuition and quality to deliver those moments in and around the box.”

The first step is acknowledging that not all long shots are created equal. This is one of the most fascinating charts of the year, from Conor O’Neill at the Athletic:

I’d argue that the degree to which teams are overperforming feels unsustainable, but there are two other big factors here. One, some players are exceptional in these zones. And two, modern blocks can open up in these spots, because they’ve been so well-trained to pack the box and deny high-xG chances.

Knowing what we know about Kroupi, does this really feel like a 3% chance at goal?

Does this really feel like a 4% chance at goal for Cunha?

There are two players who I think can reliably outperform xG from these areas: Declan Rice and Eberechi Eze. But in 9 out of the 10 league appearances following his hat-trick, Eze had zero shots. Part of the story is that he was often at RCM, part of the story was him just having trouble getting into the game, and part of the story was that he didn’t have players who were dragging attention away from him.

I’d put a target of ~3 shots a game for him.

🔥 Final thoughts

Arteta often talks about wanting to be the best at everything. To my eyes, that begins with selection. The left, the right, and the middle should all have currents buzzing through them, all carrying compelling stories to the goal, filled with good players, sure, but complementary ones that are suited for the task of the day.

It’s hard not to get excited at the idea of Havertz back, and Saka rotating into the #10, and Madueke at right-wing, and White playing more, and Eze in better positions, and Ødegaard taking his time, and Calafiori back, and, and…

Of course, there will be setbacks, too, but it’s on Arteta to commit to some dynamic groupings in the weeks ahead. Committed players are basically stable performers. Their individual form ebbs and flows less than one may think; if there are peaks and valleys to their performance level, it’s usually because of fitness or the surrounding dynamics. Many Arsenal players still have levels to unlock, and the dynamics can help achieve them.

I’d also step up some of the first-half pressure with more pressing and more chances at a crooked scoreline, which will dial down second-half stress and help key legs get rested at critical moments. Sunderland was a good blueprint. You can hit them in the first half, make the game uncomfortable, then swarm them with runners late.

The good news is that these solutions exist internally. The other good news is the league, and the game, are shifting fast, and we seem a bit ahead of the curve. The very best news is where we currently stand.

Above all, this is about how you widen your outcomes and loosen the evil grip of variance. When you stop living and dying on one route, one bounce, one finish, one set piece, shit will stop falling from the sky.

Life intervened over these last few weeks. All good stuff, thank you. But it’s good to be back. ❤️

“Hey, what can you say? We were overdue.”

— Bo Burnham

Brilliant. Great comments on Saliba, you put into words things I've sort of felt, but couldn't really label. Big Gaby is the emotional heart and soul and in terms of pure defending perhaps the best in the division, but Saliba is a wizard that can do things no other CB can. Also salivating at the kai-Saka-noni combo playing together. We really have so many looks, just gotta find the right niches for each. I'm liking the slight trend towards more directness too. We're built for that.

WE WERE OVERDUE

- a league title

- Billy Carpenter content

- a mention of the word "complementarity" in internet media