What we saw at Craven Cottage

Dubious observations from the convincing win, including: why Arsenal circulates the ball so much; how Ø contributes in defensive transition; why the rotations worked; and “The Zinchenko Equation”

Man. It’d be hard to find a consensus on the single most convincing display of the Arsenal season, but this was certainly up there. It was equal parts beautiful, thrilling, and uncomplicated — and we’ve got plenty to talk about.

Around these parts, we (OK, it’s just me) crossed the 1,000 subscriber threshold this week. I want to thank you from the bottom of my heart for all your support in the past few months as I figure out what to do with this thing.

At the moment, my inclination is to continue rolling as-is. There are so many wonderful podcasts, videos, and the like these days. I figure I’ll just continue offering these weekly long-reads for those so inclined, if for no other reason than this: it’s what I love to do.

With that, let’s jump into some observations from Fulham. Many major things will go unmentioned, as this is not meant to be an exhaustive review of the contest, just some things that caught my eye. Let’s go:

Good circulation

Whether at a youth game or a pub, watching a team play out of the back can induce anxiety in a crowd. In either case, you’re likely to hear some dad, several beers in, break the silence with something like “juuuust fuckin’ hoof it!”

The nerves are understandable. Even the best teams can generate some harem scarem moments in build-up, like when Ramsdale underhit this ball to Pereira:

Moreover, a team is likely to generate groans when pulling back from a potential opportunity in transition, all so that they can recycle it towards their own goal. Arsenal also does this a few times a game.

I’ve perhaps never seen a team do it more radically than Roberto De Zerbi’s Brighton side, who are perfecting the principles he’s been honing for years. Players will actually throw up their hands to stop their teammate from playing in transition if the conditions aren’t right, all to hit it backwards and play to their preference: building out the back, baiting pressure, and playing through.

So why do teams do this? What’s true of a person is true of a football team: good circulation is vital to good health.

In football, there are a few reasons why. Let’s look at a before and after of the second goal to gain understanding.

Here’s the before. Leno blasts it to the midfield in hopes of winning a second ball. After a couple bouncing balls, here is the situation in which Arsenal truly secures possession:

With Fulham realizing who has the ball, they start flowing back into their out-of-possession shape. I didn’t study it too extensively, but from what I could see, Fulham generally settled into a mid-high modified 4-4-2, with Pereira and Mitrović running the press from the front. The modification to a typical zonal block was that I noticed Lukić (#28) man-marking Ødegaard — or, trying to — and shadowing all his movements for much of the game.

But if you look at the above situation, it’s not inherently exploitable from Arsenal’s perspective. Fulham has numbers, and they generally have their shape. That means it’s time to recycle.

I could show you the next 15 or so passes, but that’d be a lot of uninteresting screenshots. But we should know the intent. Because Fulham is not just playing negatively in a pure low-block, like an Everton, they have a semblance of a press. And a press will have “triggers,” that is, predetermined moments that cause them to run at the ball-carrier. This can be a loose touch, a pass to a certain area, or a pass to a certain player.

The goal, then, is to invite and provoke those triggers on your own terms, in an effort to manipulate the opponent into a shape of your choosing. If you see players dropping deep only to one-touch it back to a defender, that’s generally what’s happening: they are hoping to pull a defender out of shape, and induce a gap.

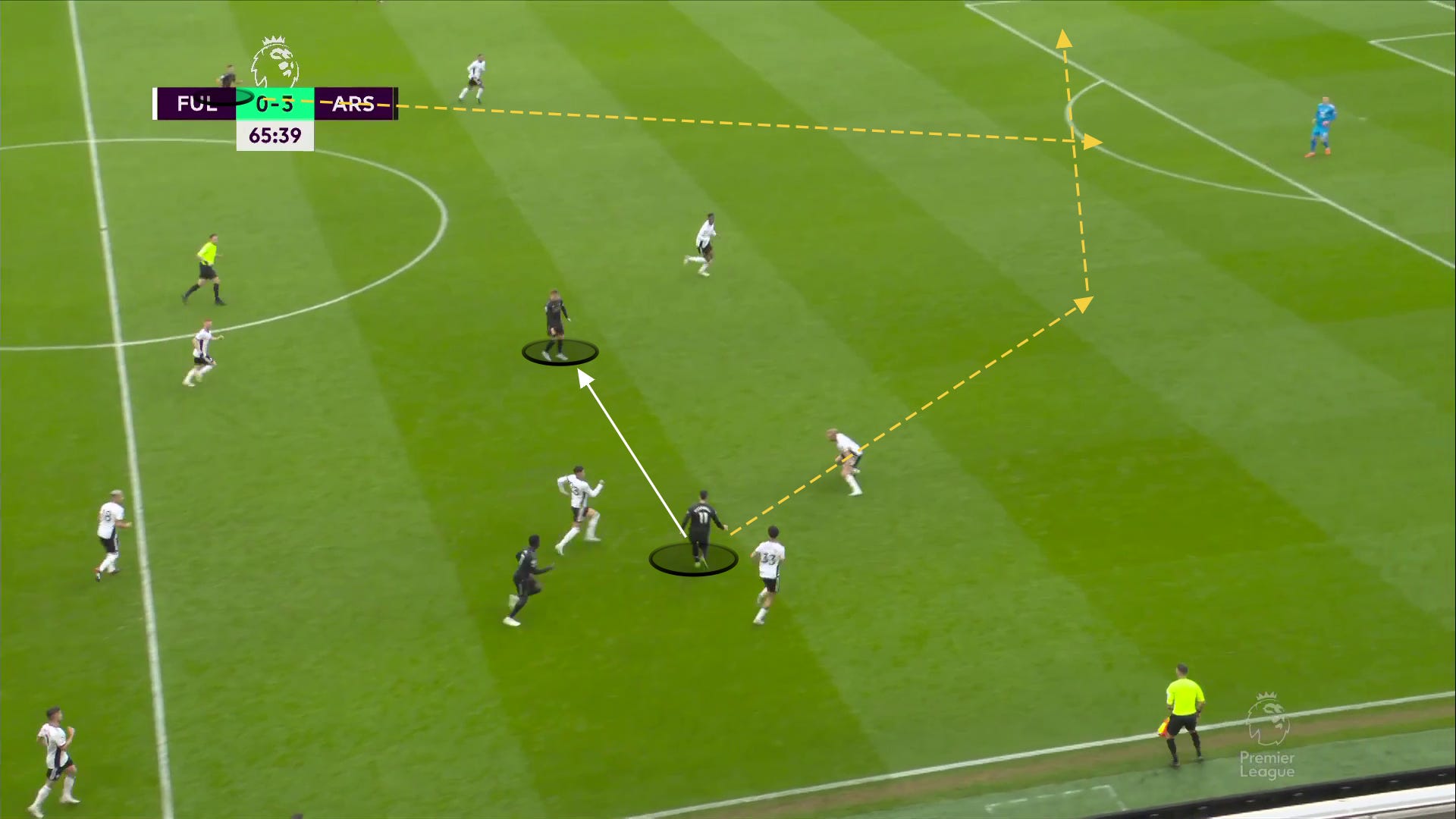

That also requires a patience for when those circumstances don’t occur, as you’ll see below. With the play on the right, White has a pretty obvious pass to Saka on the wing. But Saka is completely isolated — Ødegaard had dropped deep, so Saka would have essentially been on a 1-vs-3 with no help, all pushed against the Beefy Opponent known as the touchline. Arteta is on the record for not liking these kinds of passes. White cycles it back to Saliba instead:

Another 10 passes or so take place, with the ball going back-and-forth, right-to-left and back again. Eventually, Arsenal opts to create a little rondo drill in the corner, with the likes of Ødegaard, Thomas, White, Saliba, and Zinchenko doing one-touches to each other in a situation a lot of teams would like to avoid. Eventually, the ball makes it to Saliba.

Look at the defensive shape now. You may notice a certain vice-captain showing you what’s going to happen next:

Saliba bangs a ball over the top with his off-foot — this is why you pay for ball-playing defenders, folks — and the break is on.

And here’s the after. Less than 45 seconds after the first screenshot of Zinchenko securing possession in almost the exact same spot, Arsenal had successfully moved six defenders out of the play:

And I’m sure you remember what unfolds from there. By my count, Xhaka played it out to Trossard with the 23rd pass of the sequence; Trossard crossed it to Martinelli for the 24th (and the goal).

There can be high-wire moments when playing like this, to be sure. We can remember some imprecision against Fulham the first go-round, or the second half against Leeds, or even some loose touches last week against Sporting CP. But we should be conscious of how memory can have trouble with proportion. It’s easier to recall a mistake that leads directly to an opponent shot, than it is to remember dozens of examples of build-up that ultimately (if windingly) result in a goal on the other end.

Playing like this enables everything Arsenal is trying to do. By Ramsdale joining the build-up, you are inherently playing with numbers (11v10 in an extreme case, with the other keeper obviously out of the play), and triggering rotations in the process. By maximizing touches and possession, you are increasing the likelihood that your talent differential will pay dividends. Perhaps the best reason to do it is what we saw above: it enables a team to manipulate their opponent into a shape of their choosing.

But there’s also the psychological impact. Hoofing it long, even when there are numbers, can convey a lack of confidence, both to your opponent and your own team (unless you have Toney 😬). Playing out of the back is a way of saying I believe I have better players, and I believe our players are better-drilled.

Back to De Zerbi, who framed up the advantages this way:

“In my opinion, playing the ball long and trying to win second balls is a bet. And since I don’t like betting, I’d rather train my team to play out the back when is possible. Because that’s not betting, that’s working. And since I believe more in working than in betting, I do this. Since my teams have always had quality players, I’d rather them receive the ball on their feet than their teeth.”

Ramsdale and others will still hit it long as circumstances (and numbers) dictate, as we’ll cover later. But against a press like Fulham’s, it’s better to work than bet.

A captain defending by example

When playing this way, there is a particular set of responsibilities once possession as lost, as it’s likely to be a dangerous situation. For the center-halves, particularly Gabriel on the left, they must be comfortable on their island, and composed when facing all manner of threats.

For the others — namely Partey, Zinchenko, and Ødegaard — the responsibility is not calm composure, but immediate disruption. Their job isn’t to run with people, but to decisively unsettle the counter with any tool at their disposal, including tackles, leans, or tactical fouls. Thomas is good at this in a way that anyone can understand, and I’m hoping that the fanbase is warming to what a good upfield defender Zinchenko can be.

With that, I’d like to pay particular tribute to just how pivotal Ødegaard can be in this Øde-regard. (I’ll see myself out.)

In the 43rd minute, Decordova-Reid intercepted a loose ball and was free to break. Ødegaard — who is slower than BDR, I’d presume — starts the play back here:

…and Big Gabi uses some good angles to slow Decordova-Reid down a bit, and Ødegaard catches up, disco-sliding the ball out of there with ease. Hello counter, goodbye counter:

A similar play happened in the second half. Pereira got the ball out with a transition option ahead and sought to break through the middle, but the skipper was on his case:

Ødegaard didn’t want to risk Fulham getting any life with a through-ball to Mitrović or otherwise, and climbed on Pereira to stop the play in a place where a free-kick isn’t particularly threatening:

He earned a yellow in the process, flashing a vibe of #noregrets.

Conclusion: he good.

Some of the best rotations yet

We can overcomplicate in these parts, so let us compensate with a dramatic oversimplification: Arsenal’s worst performances are when they stagnate in their zones; their best performances are when they rotate like mad.

Not only are rotations fun, but they also play to the current roster’s strengths. When Arsenal commits to a more static 2-3-5 in possession, and park in the assigned channel on the tactics board, they are counting on a style of play that relies on pinpoint crosses and clinical finishes, two areas of the game where the squad can still be a work in progress.

This showed up in some of the Europa clashes, and was part of the reason why the Newcastle block was never truly un…blocked. The most memorable example, however, was at Goodison Park — perhaps the only time the team has been conclusively outplayed this season, without a counterargument (however half-hearted) to be made. Each player’s touchmap was overly clean, and the team was never particularly threatening as a result.

Since, that has all largely changed for two related reasons: the introduction of Leandro Trossard as a false-9/winger, and the untethering of one Gabriel Martinelli.

We’ve been harping on Martinelli and rotations for a couple weeks now. We’ll continue for a moment, because having him consistently join rotational “alphas” like Jesus and Zinchenko (and, now, Trossard) is a bit of a skeleton key. Last week, we outlined an ideal scenario:

Ideally, that means others taking on the true false 9 responsibilities of dropping deep — whether Jesus, Nketiah, or Trossard — while Martinelli holds height and makes probing runs left-to-middle on the back-line. Then, when possession settles in the attacking third, the delineation between “9” and Martinelli becomes immaterial. They’re just playing football.

Trossard’s game was so good that he generated chances from every spot he took up: false 9, wide winger, corner-taker, and true striker (how about that foot-change strike that narrowly sailed wide?).

Early in the second half, we saw something interesting that’ll add a really nice dynamic to the team. Trossard dropped deep and brought defenders with him; from there, Martinelli sprinted into the vacated space and Trossard saw a chance worth taking, looking to hit him with a through-ball that was narrowly cut off by Leno. The pass had some stank on it, and as a result, the screengrab looks like something from an Oliver Stone conspiracy film:

This rotation — the central forward dropping deep, Martinelli cutting into the void from left-to-middle like a Ronaldo-esque wingstriker, and the forward then drifting out wide left — feels like a top use of everyone’s abilities, whether the pass happens or not.

Martinelli is fast becoming his ideal self. As a last step, I’d still like to find a higher default position for Martinelli in the 4-4-2 mid-block, so he can cheat up as the highest “pinning” attacker as soon as possession is won.

Similarly, I’ve also remained intrigued by post-corner rotations. Arsenal has been generating a lot of corners of late, and have been using every option imaginable: standard lifted balls, short corner routines, grounded balls to set up long strikes, and more.

As they keep possession on second and third chances, it’s interesting to see how quickly they get back to their core positions. Many teams will look to “reset” after a second chance, as they’re worried about being exposed on a counter with players out of position.

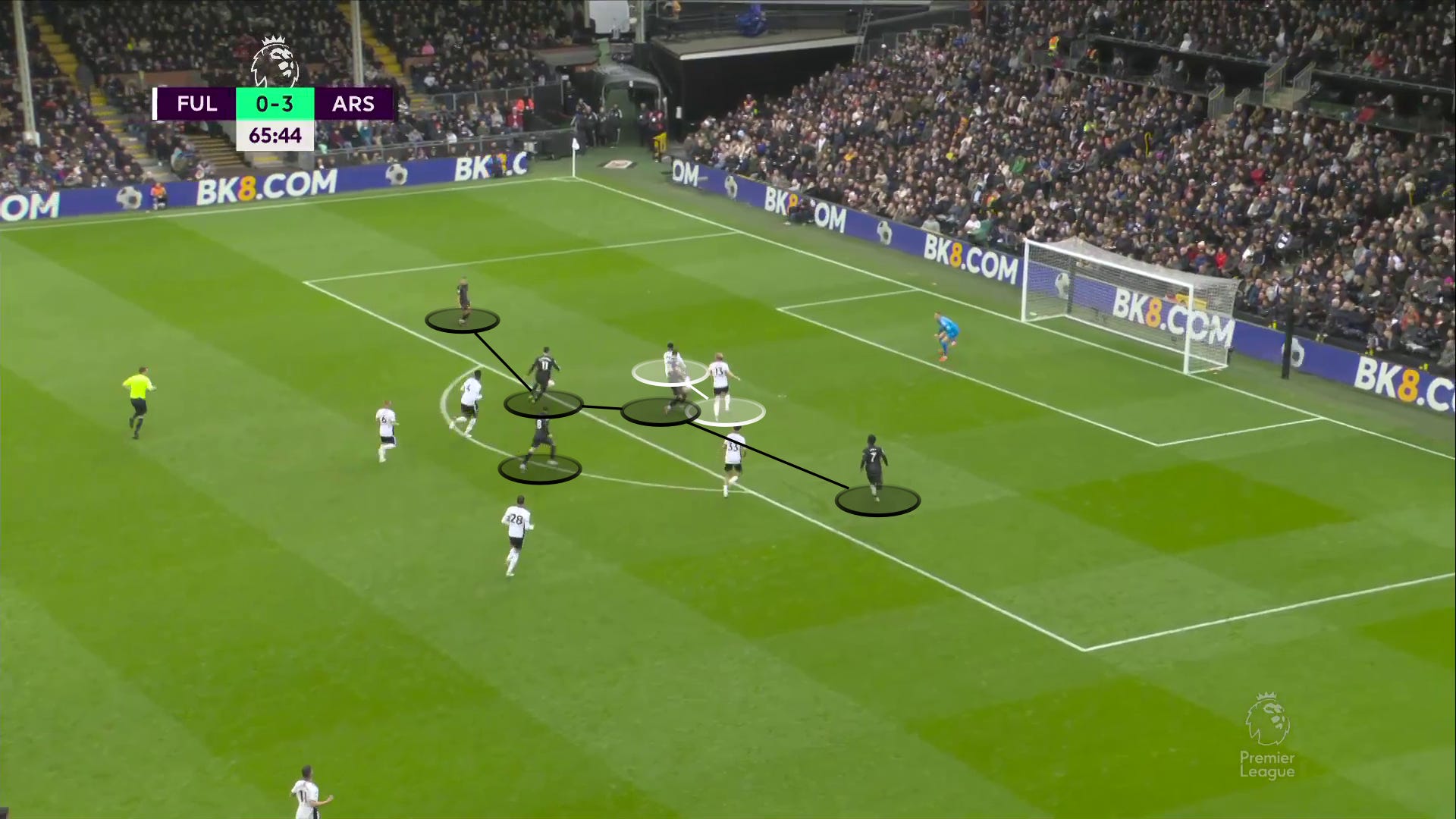

Arsenal plays bolder than that. In the below instance, there had been so many chances to reset: including a corner, a blocked shot, a recovery, a lost ball, a counter-press, and a cross. Still, only Gabriel and Saliba really felt the need to get back to their spots, and looked a little begrudging in doing it.

That meant Arsenal was attacking in their 2-3-5, except it was Partey at striker, and a midfield of Trossard, Zinchenko, and Ødegaard. Partey trusted the positional awareness of his colleagues enough that he stayed in the box looking for crosses to keep up the pressure:

…and that trust was then put to the test, when Fulham cleared a ball over the top to Pereira. Trossard — our striker Trossard — then did his best Partey impression, broke it up, and dispossessed the attacker:

Here’s the final rotational moment we’ll highlight, and one that is the exact thing you hope to see when things get a little stuck.

Fulham came out swinging in the first half, and as a result, things weren’t quite as aggressive or dynamic as they’d been in the first (which was a high bar to clear, to be fair).

As a result, Martinelli saw the left was a little crowded after a throw-in, so he decided it was time to spice things up a little — and he cut all the way across the pitch to become a right-winger, just because:

As he took up the spot on the touchline that Saka usually would, the rest of the team shifted. Saka became Ødegaard, and Ødegaard became Xhaka, forming a box midfield.

In his second Premier League start, you can see Manor Solomon trying to figure out WTF Martinelli is doing out there:

…and then, there’s some one-touch play. White plays it to Martinelli, who plays it back to White, who plays it to Partey, who plays it back to Martinelli. Saka shades back, and Martinelli delivers it to him and starts sprinting:

Saka delivers it to Martinelli, who rolls it over to Ødegaard and hits the afterburners towards the penalty circle:

…and after Xhaka lays it off for Martinelli, here’s how the chance winds up: with a 4 on 2. Martinelli probably could have laid it off to Trossard for an easier chance, but I’ll never decry the striker’s instinct that makes him shoot. It’s ultimately blocked, ending a great chance:

In a time of highly structured football, when clubs worldwide are following Pep’s example of positional play, the two teams who are lighting the world on fire are Arsenal and Napoli. Both share some characteristics — playing out the back, adaptations of a 4-3-3, excellent wing play, dominant CB’s, secure midfielders, high press/counter-press — but this positional freedom is perhaps what sets them apart.

Here’s what Napoli manager Luciano Spalletti had to say earlier this year:

“Systems no longer exist in football, it’s all about the spaces left by the opposition. You must be quick to spot them and know the right moment to strike, have the courage to start the move even when pressed.”

Arteta has a system, alright. But there’s an old quote about the word grace: “Grace is the beauty of form under the influence of freedom.” That feels like an accurate way to describe Arsenal at its best.

On Napoli: it’s a shame we won’t get to see the two sides battle it out this year.

The Zinchenko Equation

We’ve talked about build-up; we’ve talked about high counter-presses; we’ve talked about rotations. It’d be a shame if we left Zinchenko out of the discussion.

Zinchenko can alternate between solid games and world-beater games, and when the performance falls in the former category, it can be tempting (for some) to single out his lowest moments, and ask the relative cost of his style of play — wondering, in turn, if more rotation should take place at the position.

I am not among their ranks. I believe doing so dramatically underestimates the sheer scale of Zinchenko’s contributions.

Bournemouth is a recent example. In the come-from-behind victory, Zinchenko committed a total of 119 “actions,” and that included 94 pass attempts. According to Wyscout, he lost the ball 0 times in the Arsenal half, but recovered it 11 times in the Bournemouth half. This all helped pin the attack forward and continue with the urgency needed to win, including several moments that proved decisive.

Broadening the timeframe, here’s a brief comparison between the Zinchenko of this year and the Tierney of last, with caveats abound:

As you’ll see, I threw in a couple made-up stats: such as “losses per successful pass” and “ZINA,” a truly bullshit stat that weighs how much a player wins it in the opponent’s half compared to how much they lose it in their own. Tierney’s numbers even out; Zinchenko wins it +1.52 more times than he loses it.

More than the raw numbers, though, is the scale. Zinchenko is passing 23 times more per 90 than the Tierney of last year. If you were to scale up his numbers, and extrapolate Tierney’s efficiency to 23 more passes, he’d lose the ball 15 times per 90 (~5.5 more than Zinchenko), and have 4.4 losses in the Arsenal half (compared to 3.05 for Zinchenko). We can’t say with a lot of confidence how it’d look given a long run in the new system with the updated personnel, but this gives us some context.

This is no knock on Tierney, a wonderful player. There just will always be a shaky moment or two when a player is tasked with such volume, and one can’t safely assume it’d be made up elsewhere, whether we’re talking about passing or aggression. It is also true that Zinchenko can batter weaker sides but lose the ball a bit more against top sides, and that’s something that can be improved.

But we musn’t nitpick too hard. This shit is not normal:

Finally, I’ll call out something that doesn’t show up in the stat sheet. Whenever Arsenal scores, the team naturally sprints to the scorer. I’ve noticed Zinchenko almost always makes a run for the player who made the decisive action beforehand, wherever it was: Trossard for the assist, Thomas for an upfield line-breaking pass, etc, etc.

(Unless he gets hooked-and-held by a defender on a corner. Then his attention is drawn there.)

This shows how locked-in he is, of course. But what a teammate he seems to be.

…and finally:

Gabriel Fucking Jesus

That’s it. That’s the section.

OK, that’s it for now. Hope you enjoyed this week’s edition.

May your week be joyful, and if you happen to trip en route to an open goal, may the ref award you a free kick for your troubles.

And happy grilling.

🔥

great easter grill out!