Beat United and it feels so good

Examining an uproarious win, including: the hidden benefits of bigness; the evolving defensive structures; the inevitable mistake; the Zinchenko/Rice pairing; and how to unlock the middle

Depending on how you use it, the word “fine” can mean any of the following:

(Noun) Money extracted, as a penalty

(Adverb) With a very narrow margin of time or space

(Adjective) Pleasant; free of impurities; superior to the average; characterized by elegance or refinement or accomplishment

At varying points on Sunday, all three felt apt. Thankfully, it ended on the final, most upbeat definition.

A fine game. Mighty fine. No notes.

We’ll dive into all the nerdy shit here in a minute. But even with the calming effect of time on my side, and all the complexities we have to discuss, please make no mistake — my final analysis is “fuck yes.”

🎢 The small benefits of bigness

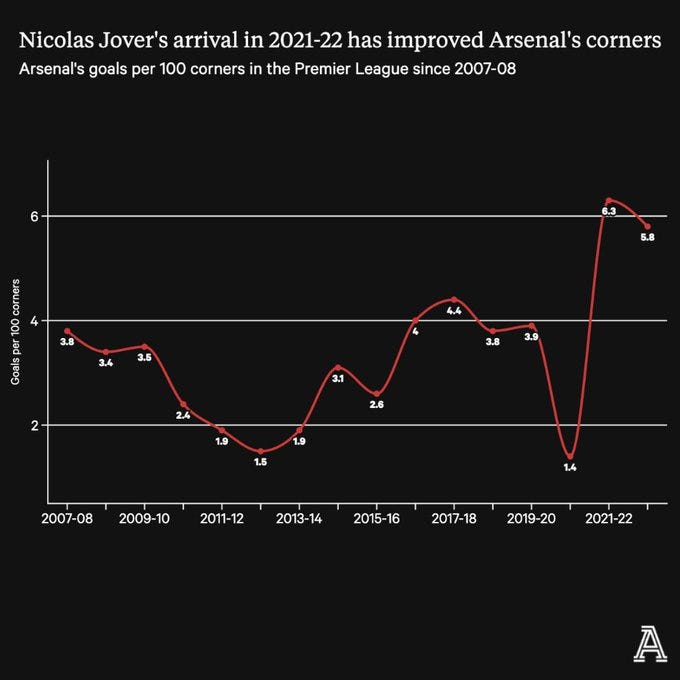

There has been some brilliant analysis of the Arsenal corner routines. I’d suggest you start with Ahmed Walid’s piece at the Athletic, diagnosing how Nicolas Jover engineered an approach to eventually set the Emirates ablaze.

There’s a clear delineation between the pre- and post-Jover eras:

Last week, in Frustrated after Fulham, we talked about how Arsenal’s “Big Guy Ratio” was off in the late dagger of a corner, as it often is when this team gets hit. Through a string of substitutions (or omissions) — there was no Gabriel, Vieira was in for Havertz, Thomas was out, etc — Fulham was allowed to isolate Palhinha on Saka through the middle and induce both a mistake and a disappointing draw.

This was against the grain of Arteta’s vision for the team. Through the additions of Declan Rice and Kai Havertz, the squad has signaled a desire to improve its physicality, enhance its ability to go long, and widen its window of tolerance in tight games against big opponents.

This evolving approach — in a lineup featuring Rice, Havertz, Gabriel, et al — paid dividends against Manchester United, including in ways which may not immediately meet the eye.

Arsenal were, quite visibly, the bigger side. The opponent, anchored by an undersized CB pairing of Lindelöf and Martínez, featured Casemiro as a plus aerial threat … and that’s about it. Otherwise, it was a mix of ordinary performers and liabilities in the air.

The first impact was on Onana’s long-balls. So deft at finding the free man, Arsenal dialed down the press and thus, the likelihood that there was a free man to find. This resulted in balls over the top to physical mismatches in Arsenal’s column. Onana will always be impressive with the ball, but all considered, you basically term this a win, go home, and pop on the episodic drama of your choice:

This size also showed up in the underlying stats. Arsenal won 63.6% of their defensive duels, 10 more duels overall (76 to 66), and recovered the ball 10 more times (70 to 60).

There were a lot of moments in the midfield like this. What you’ll also notice is just more Arsenal players around, because they weren’t baited as high:

But I want to zoom in on an aspect of the game that isn’t discussed as much: the importance of generating corners, and the impact of set piece mismatches throughout the game, not just on the set pieces themselves. Any opponent of Dyche, Frank, or Moyes is familiar with the crippling feeling one gets when a ball goes out of play behind your goal.

This is for good reason. Say a good team has a 6% chance of scoring on a corner. If they are able to generate 12 corners for themselves, and I remember how to do this kind of problem, we can use some complementary probability to determine the chance they score at least once from them is 52.4%.

Arsenal did earn 12 corners in this one, which was the most since six months ago against Bournemouth — yes, that Bournemouth game, which ended with a set-piece delivery to Reiss Nelson you may recall.

Which brings us to Martinelli. Facing a brilliant 1v1 duel specialist in Aaron Wan-Bissaka, and with a set piece mismatch looming, Martinelli was able to call upon a wider range of moves. It’s often thought that the best dribblers are purely proactive, but that’s not true — if you watch Messi, Saka, Vinícius, etc, you’ll noice how reactive they are, driving at the defender and monitoring for lunges or heavy steps, then pouncing at the moment of maximum vulnerability. Despite all his exploits, Martinelli can still be guilty of predetermination.

On Sunday, he had all options available to him. Of course he’d like to cut inside and shoot, but if he was led to the line, that was success — because that was a corner, and another mismatch in the air:

One more corner, please:

I think I counted 6 in all from Martinelli, plus another wide free kick after a foul.

With each, the odds kept increasing: of the 12 corners Arsenal generated, they were able to get shots off on 7 of them.

Now, this is always a part of Martinelli’s game, and generating corners isn’t the only benefit. After a few near-misses on them, United may have become increasingly wary of his runs to the byline.

Here, assisted by a Tomiyasu underlap, three United defenders play it low as Martinelli decides to cut back and weave through traffic:

This kickstarted perhaps the most beautiful attacking sequence of the day, in which Martinelli worked it into Jesus, who worked it back out, and back in again. Perfect rotations meant that Saka was sprinting through the half-space:

In the below clip, if you so dare, try and find when Jesus looks to track Saka making the run through the middle (you won’t find it). He could feel him there, and backheeled it to his foot:

And it all started out wide left.

On the day, WyScout credited Martinelli with 11/13 (85%) dribbles won against an imposing 1v1 specialist; forcing him outside had a greater cost than usual. Raw percentages don’t always matter that much, of course, but I trust that you can treat that with the appropriate nuance. He helped generate corner after corner until the dam eventually broke after an Ødegaard deflection.

I talk about marginal gains reverberating throughout the pitch, and there’s one example that sounds too spurious to be true: by Arsenal having a huge size advantage on set pieces, Martinelli becomes a more dangerous 1v1 dribbler.

🤔 How are defensive structures evolving?

The last time we saw Manchester United, punches were flying in the stands of MetLife Stadium in New Jersey.

A bit of a boxing match took place on the pitch, too. Arsenal were pressing high, and ten Hag was happy to take the hits — pushing the ball over to Wan-Bissaka, rotating through the midfield to isolate Rice on a player, then having keeper Tom Heaton blast it over the top.

These long-balls can have different objectives. Sometimes, their aim is to beat the defensive midfielder 1v1. Sometimes, the objective is to pull that defensive midfielder out of the middle, so others can flood the vacancy. That was the case here:

From there, with White out wide, Bruno could attack the open space. This is where he scored from:

This is the exact kind of opportunity Arteta is working to counteract.

He’s been varying his approach since, as was evident on Sunday.

♦️ First, that friendly against United may have resulted in Arteta nixing a possible defensive set-up. With Timber inverting from right-back, Gabriel became the CCB in possession and in the “rest” shape (i.e., the shape that Arsenal are often in when they lose the ball). It led to some awkward moments, with Gabriel biffing a high ball for a Sancho goal, and Saliba having some weird defensive adventurousness up the right touchline that got exploited; they were essentially offering pale imitations of each other. Saliba may be the best CCB profile in world football, and Gabriel is probably top-5 as an aggressive, wide left-footed LCB, so Arteta understandably has played them back to their strengths, with Saliba looking like a matchup-proof CCB (whether that’s ultimately on the left or right in the block).

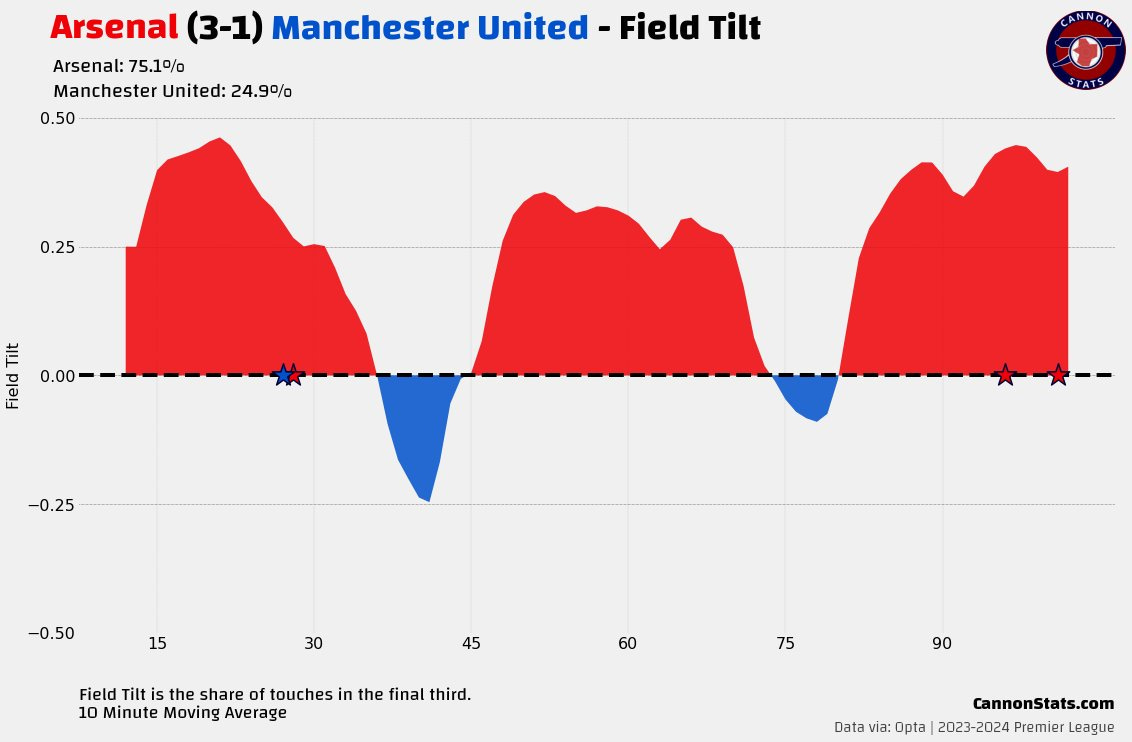

♦️ Second, the team now plays lower when necessary. To help understand how, passes per defensive action (PPDA) is a rough approximation of the intensity of a team’s high-press, giving a sense of how many passes a team allows in the opponent’s 60% of the pitch before intervening. In this game, they had a 16.14 PPDA, which was their lowest amount of intervention since the Community Shield, when they posted 21.37; both of those numbers are lower than any game last year, aside from that strange Bodø/Glimt frozen turf game that should be banished from the statistical record books. As Arsenal know all too well, you can’t play in transition against a team that doesn’t allow you to.

♦️ Third, Declan Rice’s role has evolved.

Here’s what I wrote after observing some defensive openness in the pre-season:

He likes to cover everyone — which means, either, he had to chill and sit a bit more — or, teammates have to dash and cover his vacated zones (usually Zone 14). Likely a combo of both. Right now when he covers low, specifically between LB and LCB, his spot is often left open.

He’s a player worthy of schematic adjustments, so my semi-megamind thought would be to get him to sit centrally in a 4-1-4-1, and have the ball-side 8 jump aggressively and Rice fill in, which keeps it a 4-4-2 in all but name.

He’d be more central, less draggable, and more unavoidable that way. I don’t know. Probably unlikely.

Folks, we did it:

Here, you can see it in action — with the ball out to the United left — which triggers Ødegaard to join Nketiah up high, Havertz to join the mid-block, and Rice to swing over:

I like this for a lot of reasons. The first is that it plays well into the abilities of Havertz and Ødegaard, who aren’t prototypical blockers like a Xhaka, but have so much energy and enjoy running directly at players, and still have the discipline to get back and clog lanes on the far side. The second is that it makes Rice more unavoidable, and less likely to get yanked to the touchline. This counteracts the opponent’s ability to just work on the other side of Rice: he’s always there.

And finally, I like this because it offers a simpler transition from the pressing shape, which is roughly a 4-1-4-1 anyway. Here is an overly-simplified view of what a press could look like on a day like this, when the plan was to challenge Onana less directly, drop back a bit, stay compact, and push play through the United right:

Whereas the team has previously been exploited when transitioning from their press to the block, this keeps everybody closer to their eventual positions. In theory, at least.

In practice, the opening stanza was a little confusing to watch. There was clearly a plan to have a less “interventionalist” pressing approach, and engage United’s build-up with much less ferocity than usual.

In practice, almost everybody was a little uncertain, or generally risk-averse. There was a complexity to the pressing “triggers” — i.e., what a player sees that causes them to jump — that I’m not certain I (or many of the players) fully followed. This caught the ire of Ødegaard, who could be found screaming at everybody for most of the first half.

Here’s him yelling at Saka to jump up:

Here’s him disappointed in Martinelli for going high instead of covering wide:

Here’s him screaming at Havertz and Martinelli to press the wide men instead of maintaining compactness:

…and here’s him telling Havertz to jump on Lindelöf:

He was clearly stressing for more direct action from his teammates, who all seemed focused on not getting pulled out of position and leaving lanes.

Regardless, much of this discipline — if you want to call it that — showed up in the United build-up play, which certainly had its moments, but was generally sleepy, and got pushed to the side of Arsenal’s choosing:

The teams potentially shared early objectives, as well. Whereas United wanted to calmly keep possession and suck the energy out of the Emirates, Arsenal may have been gun-shy from recent mistakes, and content for the initial period to pass without a mistake.

🤬 The inevitable early mistake

The mistake(s) came, however. As you’ll see, it came as a direct result of Arsenal starting to dial up the press to the highest levels of the game so far:

With things looking a little iffy in back, Casemiro dropped to provide assistance. With the tempo of the game spinning up a bit, Rice wanted to make a determination on whether to run with him or not. He looked back, likely to see if White was high and wide as a full-back or providing coverage, and saw that Arsenal still had a 4v3 in the backline. He concluded he could indeed sprint up and try to win the ball:

His running had the desired effect — he deflected a pass from Wan-Bissaka, which went to Nketiah, and created a potential loose ball situation in the box. This is the exact kind of chaotic situation you are hoping to create with a press:

The ball went out to Havertz — who made a bad decision to try and wand the ball to a central Ødegaard, without any pace on it. This allowed Eriksen to step in and steal it, and kick off a counter the other way.

Still, the numbers were on Arsenal’s side. Arteta is fully unsurprised about giving up an opportunity or two like this in exchange for the team’s forward lean. It’s up to the players to snuff it out:

And Rashford has it in the box for a 1v2. White’s initial read is perfect — to aggressively cut out his ability to cut back to his right, and allow Saliba to fill in below. But unfortunately, he loses his mettle and steps in too far, allowing Rashford to get back inside. White and Saliba do a coordinated riverdance to no avail:

I think Rice essentially made the right call to jump up and generate an opportunity, knowing there was support behind. Havertz should have either pushed the advantage with more assertiveness, or played it safer; a loopy roller through the middle was basically the worst of available options while the team was stretched and high. And still, there were enough numbers to stop the opportunity the other way. This one is basically on Havertz and White — not to mention Rashford’s individual brilliance. How can a nice person be so cruel?

From that point forward, Arsenal were a little less likely to jump up and get pulled out of their block again, and United were more defensive in their lean.

Later in the game, Gabriel and Tomiyasu actually found themselves in a worse situation — a 3v2 for all intents and purposes — and performed better:

Højlund probably angled his run the wrong way, but Tomiyasu nonetheless managed to cover two players at once, and perform the first role of a defender in transition: to delay.

Gabriel — enormous all day — looked fairly unbothered, and just sucked the wind out of the attack until reinforcements came.

⚡️ How progression and control is changing

To help understand how Arsenal have changed, and how the build-up dynamics feel a little different, I pulled a few different sets of numbers.

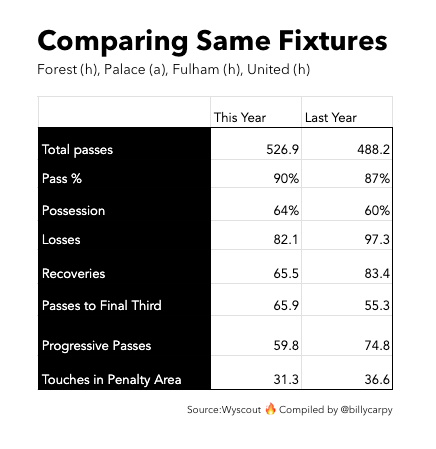

Grabbing the same four fixtures from last year — most of which were also early in the year — here is how things stack up:

The numbers paint a fairly clear picture: more passes, more “control,” but less chaos (both welcome and unwelcome). Arsenal are attempting ~50 more passes a game at a higher completion percentage, losing the ball much less but picking it up much less as well. As a result, they find the opposition more settled, and find it more difficult to string the incisive pass as a result.

On the other side, we can see how opponents are treating this Arsenal differently:

At the beginning of last year, Arsenal only got, let’s say, 80% of the Man City treatment — now they’re getting the whole thing. Opponents are sitting back much more, engaging less, losing the ball fewer times, and passing less.

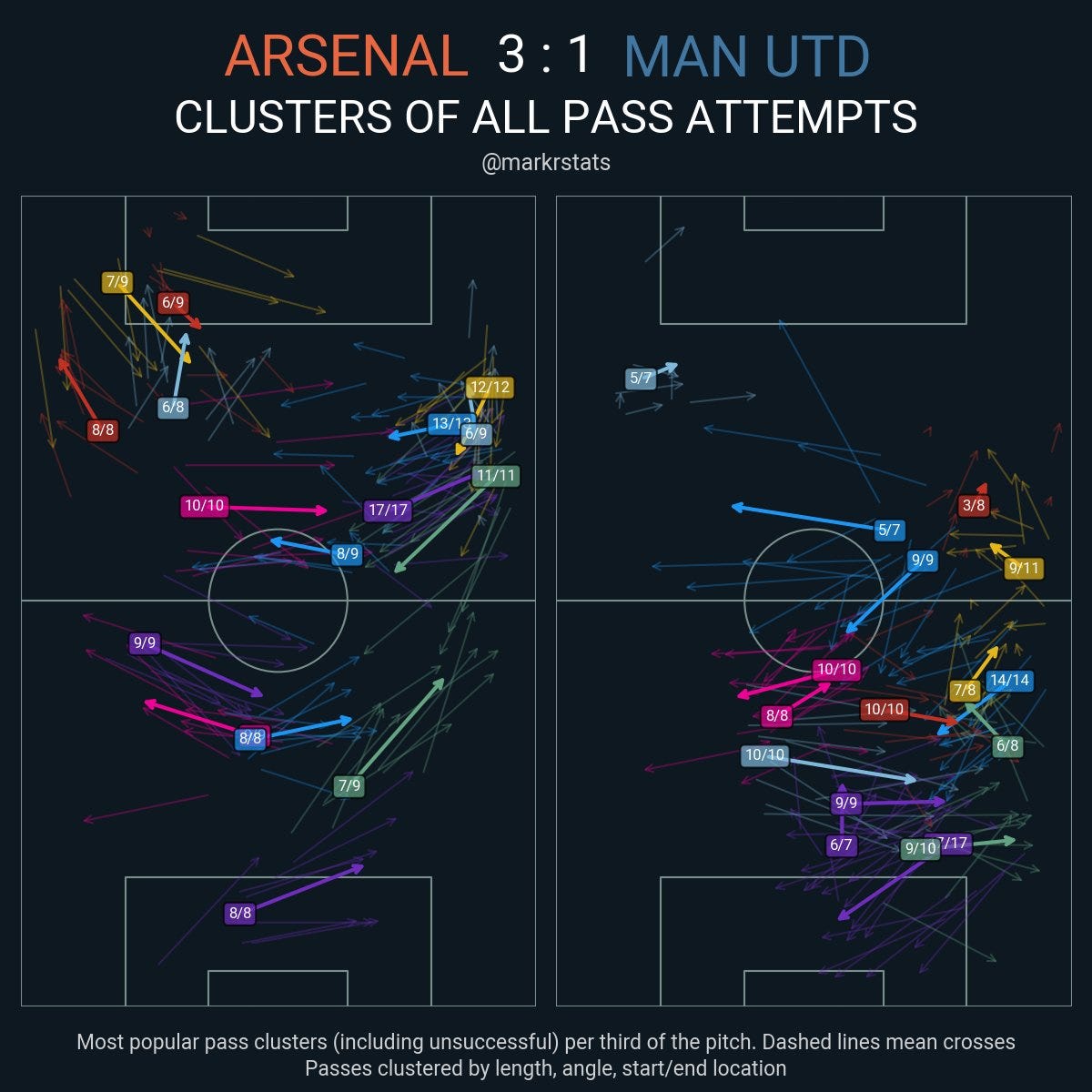

Next, let’s compare the passmaps from this year’s game to last year’s.

You’ll notice a few things:

Both the 6 and Zinchenko are a little more laterally free than last year, and less constrained to a side. This is not necessarily because of any bias on Rice’s side; for one, he can cover more ground, and for two, Jorginho’s maps also look a bit like this.

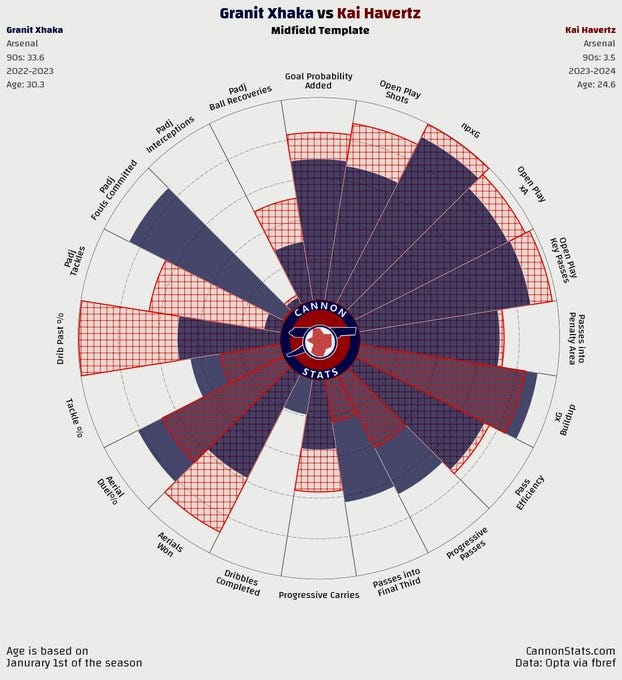

Xhaka had particularly-involved game against United last year, and had a few killer passes on wide overloads with Martinelli. This wasn’t necessarily an indicative game, but shows what he could offer when this was needed. Havertz is not here to be high-touch.

As far as Zinchenko goes, you may have noticed him receiving between the CB’s and then moving forward, and also occasionally flipping with Rice, including early:

I wouldn’t overindex this. It was mostly just the product of where some bouncing balls wound up. It is true that these two may be less eager to flip back in those situations, as they’re both happy as passers on either side, but I don’t think it points to some major schematic change.

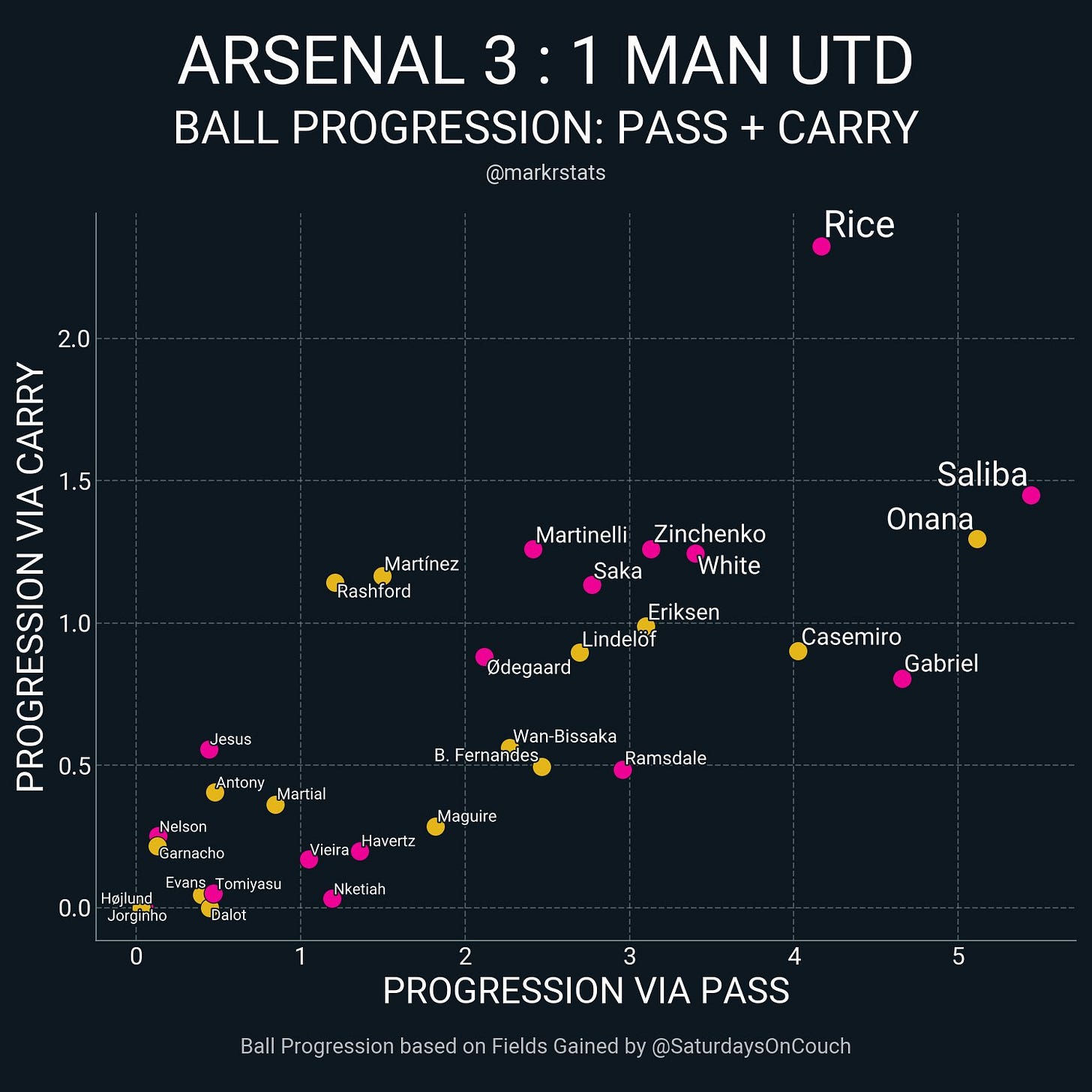

🍚 The Rice difference

Which brings us to Rice, who had a dream of a day, shielding the backline to a one-of-one standard, and ending as the game’s hero.

Most intriguingly for the future, he is starting to do stuff like this already — forgoing the obvious pass in his own box to manipulate flow, pull Bruno around, and break the lines to Zinchenko. This is the equivalent of when the velociraptors learned to open doors:

I thought I couldn’t be a bigger fan of his before the season, and he’s still surprising me with how quickly he’s picking some of this shit up.

But I’ve done enough of the (much-deserved) hagiography. Let’s add some nuance.

Rice is outperforming his West Ham self by a huge margin in terms of passing, control, and touches. But even with the increases in Arsenal’s possession, he’s still touching the ball less and pushing it forward at lower rates than Partey last year:

With games a little less open, there are fewer lanes to attack. But it also has a bit to do with the location of touches.

Positionally, Rice interprets the role a bit more like Jorginho than Partey, who can look to stick in certain pockets on the right instead of roaming more on both sides. That said, I pulled the first full Jorginho game that came to mind — at Villa, so be wary of my selection bias — and you can see the difference in pass receptions in central areas:

There are understandable reasons for this. Rice is even more intent on supporting the backline, can still opportunistically jump forward for off-ball runs or dribbles, and is likely facing more compact blocks. He also likes laying back and hitting switches.

Regardless, he can probably serve to receive the ball from the CB’s within these zones more to help move defenders around, instead of always looking to play around the block.

🔓 Unlocking the middle

There’s another, likely obvious, thing that can help unsettle central areas: more Gabriel Jesus. As we’ve covered, Nketiah has been marvelous — his game is increasingly full of detail, control, savvy, and endless effort. Whatever Balogun’s potential, it’s clear to see why Arteta would have leaned his way.

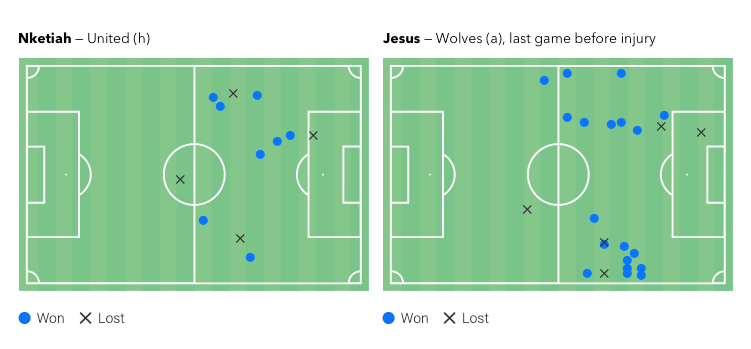

Jesus is still Jesus, though. Whereas Eddie can drop to provide support, then be anxious to get back in front of the goal for, you know, goals — it’s hard to imagine a better helper than Jesus. Here’s Nketiah’s received passes compared to that of Jesus in his last game before he picked up the knee injury:

It’s been reported that the Havertz and Rice acquisitions were interlinked, with Rice providing the platform for a more strikery midfielder in that role. Arteta also has shared about the importance of relationships on the pitch. I have high hopes for the Jesus/Havertz complementary relationship.

With a deep, interlocking squad list, it’s understandable to conclude that Havertz should be most locked-in as an attacking midfielder alongside Jesus, or as a target man striker, and should perhaps rotate more when Nketiah is in (and we’re not opting for the 3-4-3 diamond we saw against Forest).

Their stylistic overlaps, among many other factors, helped explain why deep passes were a lower-percentage affair, with the team completing 26-of-58 attempts:

Instead of talking about why it didn’t work, let’s talk about when it did.

For much of the proceedings, Havertz was essentially man-marked by Casemiro, who would drop all the way into the half-space and make it a back-five, which made it crowded for the surrounding attackers:

For whatever Casemiro’s current issues with defending in big spaces, he’s still absolutely elite in these situations. So, like Rice, you’d want to move him around.

For Arsenal’s first goal, Zinchenko swung out wide and Havertz dropped deep to offer himself for the ball — dragging Casemiro out of the edge of the box in the process:

Once the play is progressed, Casemiro is now playing catch-up instead of being parked in the danger area. This causes both United CB’s to go out all the way to that zone as Nketiah playmakes, vacating the spot where Ødegaard scores from:

Later, Rice pushed forward with a carry, and Nketiah dropped into the central area — this pulled Lindelöf out, and gave room for Havertz to cut for the penalty-that-wasn’t:

If ever there was a clear example of the promise of this role — vacating, playmaking 9’s, filled by a bombing, off-ball left-8, this was it.

Whatever the situation, Havertz had a rough first half with the ball, and I won’t claim otherwise. This is a period of mutual adjustment, and his teammates are still learning when to pick out his runs, but he is here for a highly variable outcome (goals) and is not providing it at the moment. In the second half, the desired energy was more present.

Still — it’s a very, very small sample size, but if this is his floor, the ceiling must be pretty high:

His presence hasn’t had the detrimental impact to the defensive structure that many assumed; in fact, it may be the opposite. Even more, his shortcomings as a standard midfielder haven’t caused a lack of “control,” as it would commonly be defined:

In fact, Arsenal may be too precious with the ball at present.

That said, the team has been over-reliant on a mechanism of attack (wide area overloads), and hasn’t been quite as open, direct, and progressive with immediate passing, especially after winning the ball. He’s contributed to that, and isn’t offering the bailout deeper playmaking that Xhaka could.

But it’s not complicated: contribute some goals, and we’re good here.

🔥 Final thoughts

With a team so young and talented, new looks being honed, and emergent relationships being discovered and formed, my conclusion is similar to a much more disappointing result last week:

Continue to build upon tactical and technical superiority, fuck up less, and score more. Whether you find that analysis satisfying and/or encouraging is up to you. It’s natural to be impatient for the next step.

The tactical scaffolding has all the makings of a dominant side, but there are still some final adjustments to make it hum. The updated defensive looks are promising. The reintroduction of Gabriel Jesus is likely to have cascading impacts. Rice is a fucking monster. Havertz, hopefully, gets more comfortable and confident, but is still excelling in a few key aspects. And I, like you, am anxious to see 5 goals go in the net once we’re back.

I have so many other thoughts. Here’s a speed round:

Only Saka can get awarded a free kick and then get booked for it.

(It was the right call.)

You may have thought the team left depth a little tight in the transfer window, especially with the Partey injury. I’d generally agree. While I see the importance of discipline here — Reuell Walters is better than a long-term impulsive signing, the squad is packed as it is, and somebody like Kiwior should offer more depth this year — there’s still a lot of dependency on Saliba and White. That withstanding, United is riddled with injuries, and our depth probably won the game on Sunday.

I’m good with Ødegaard floating a bit more, or switching a bit when things get stuck, but no: I’m not all that interested in him moving to the left. He has an automatic shot mechanism from the spot and he can keep doing it for 15 years as far as I’m concerned.

Dummies love Vieira because he kicks the ball real good. Coffee shop intellectuals have concerns about his size, physicality, and eventual position. Geniuses love Vieira because he kicks the ball real good.

To credit United for a minute: whatever his last-minute slide — some say he’s still sliding — so much of their game hinged on Dalot’s ability to stick with Saka; he put in quite the shift … Rashford is one of the only wingers in the world who can give White problems like that … Speaking of problems, Bruno-to-Højlund looks like it could one down the line.

I generally think that Saliba and Rice are taking the right kind of measured risks when dribbling through the middle; they are usually supported by two CB’s behind, at least. Letting a block get overly comfortable carries risk of its own. Their current execution just hasn’t been fully up to their own standards yet.

Tomiyasu full-backing through the middle was interesting. If he’s free of a certain kind of yappy presser (think Gallagher), he can usually make this work. He looked pretty confident and bursty, and is getting more adventurous up top by the week.

I try to stay out of the #TakeZone, and it hurts to say, but I personally believe Raya is a bit better than Ramsdale at this stage in their respective careers — which is no knock on Ramsdale — and expect him to grab the starting job pretty soon, as some reports have recently suggested. I hope this decision doesn’t come as the direct result of a specific mistake. I don’t like players being punished for singular, high-variance moments; for keepers, especially so. It should be about a “macro” vision for the team.

When Reiss Nelson carries a ball directly at a full-back, he induces a feeling that is only reserved for the true star tier. He’s been a bit forgotten after his preseason injuries, but that 1v1 quality is so needed as practical Saka depth, wherever it comes from. It’s thought that Arsenal are short on right-wingers, which isn’t all that true. They just need that.

I think that’s all I got.

To conclude, I will repeat my initial analysis: fuck yes.

Happy grilling everybody. ❤️

Really good feel for the game 👏🏾

I too am a touch worried about a lack of central progression but Jesus is coming 😀

Simply put - the best source of Arsenal content out there