Before the storm

A sweeping look at Arsenal’s last few performances against Real Madrid, Ipswich, and Palace — and the subtle tactical lessons they'll carry into a monumental semi-final against PSG

“I remembered a psychiatrist once telling me that I gamble in order to escape the reality of life. And I told him that’s why everyone does everything.”

— Norm Macdonald

The last few weeks have summed up Arsenal’s season in miniature. A glittering display of control and incision knocked the mightiest of foes out of Europe, providing lifelong memories for the faithful. It’s hard to overstate the significance. This was shortly followed by a show of structure and movement to dismantle Ipswich, which contributed to a sneaking suspicion that the team may be peaking at exactly the right time. Then — like the whisper of memento mori in a returning general’s ear — came a draw against Crystal Palace, filled with availability questions, lethargy, a backline mistake, and a lapse on a defensive set piece.

There’s context, sure. The stakes weren’t especially high, several players were rotated or rested or injured, and the energy dispensation was … conservative. In a similar situation in France, PSG just posted their first loss of the league campaign despite rolling out their strongest eleven.

But it all felt a little familiar, and you’d still like to have won. Fucking Mateta.

The Real Madrid tie was a reminder of just how good this Arsenal team can be. The side attacked and defended as a lock-tight unit, populating both boxes with ample numbers, and without exception. Arsenal prevailed in all aspects — in-possession, out-of-possession, set pieces, transitions, effort, tactical clarity, moments of brilliance — often using the build-up phase as a long wick to light the attacking third aflame. David Raya brought tempo from deep as Arsenal stretched, teased, then punched through Real Madrid’s shape.

The Ipswich performance had altogether different characteristics but was similarly incisive. Against Palace, however, another three points became one. Arsenal completed 235 more passes, held 13% more of the ball, and had nine fewer turnovers than usual — and yet, that all amounted to 10 fewer touches in the penalty area. The lateral passing more than doubled when compared to season averages, and the defensive duel win rate plummeted to 40%. Arsenal won just 3 of 18 aerials.

As Arteta said post-match:

“I think we never found enough consistency in actions to win the right to completely dominate the game. We had periods of that. And then we started to give those sloppy balls away. We dropped the standards in certain defensive habits as well.”

Much of this was about saving legs. But the difference in how Arsenal players performed also had to do with personnel, opponent shape, and midfield coherence. Today, we’ll get into Ødegaard’s return to the pivot, what Rice looked like as a #6, and how the differences in lineups affected wide build-up. And yes, we’ll talk about Merino. Because he might just be proving himself indispensable for what lies ahead.

Let’s dive into what worked, what didn’t, and what it all might tell us about the upcoming semifinal against PSG: another opponent who’ll challenge Arsenal’s ability to impose our style, manage transitions, and achieve clarity in the final third.

First the good, then the ugly.

👉 Fluidity against Ipswich

At Portman Road, the most notable change was in midfield.

With Thomas Partey unavailable, Arteta rolled out a midfield three of Declan Rice (#6), Mikel Merino (LCM), and Martin Ødegaard (RCM). That trio was my preference heading into the season, and is the one we’d expect to see in the first leg against PSG, pending Merino’s health.

Ødegaard was preposterously active. In a performance that harkened back to his play down the stretch of 2024, he was involved early and often — not content to sit in that right pocket, but looking to get on the ball as much as possible. The Leif Davis red card played a factor, but it wasn’t the only one.

He had more touches than any game since a 6-0 romp of West Ham last February.

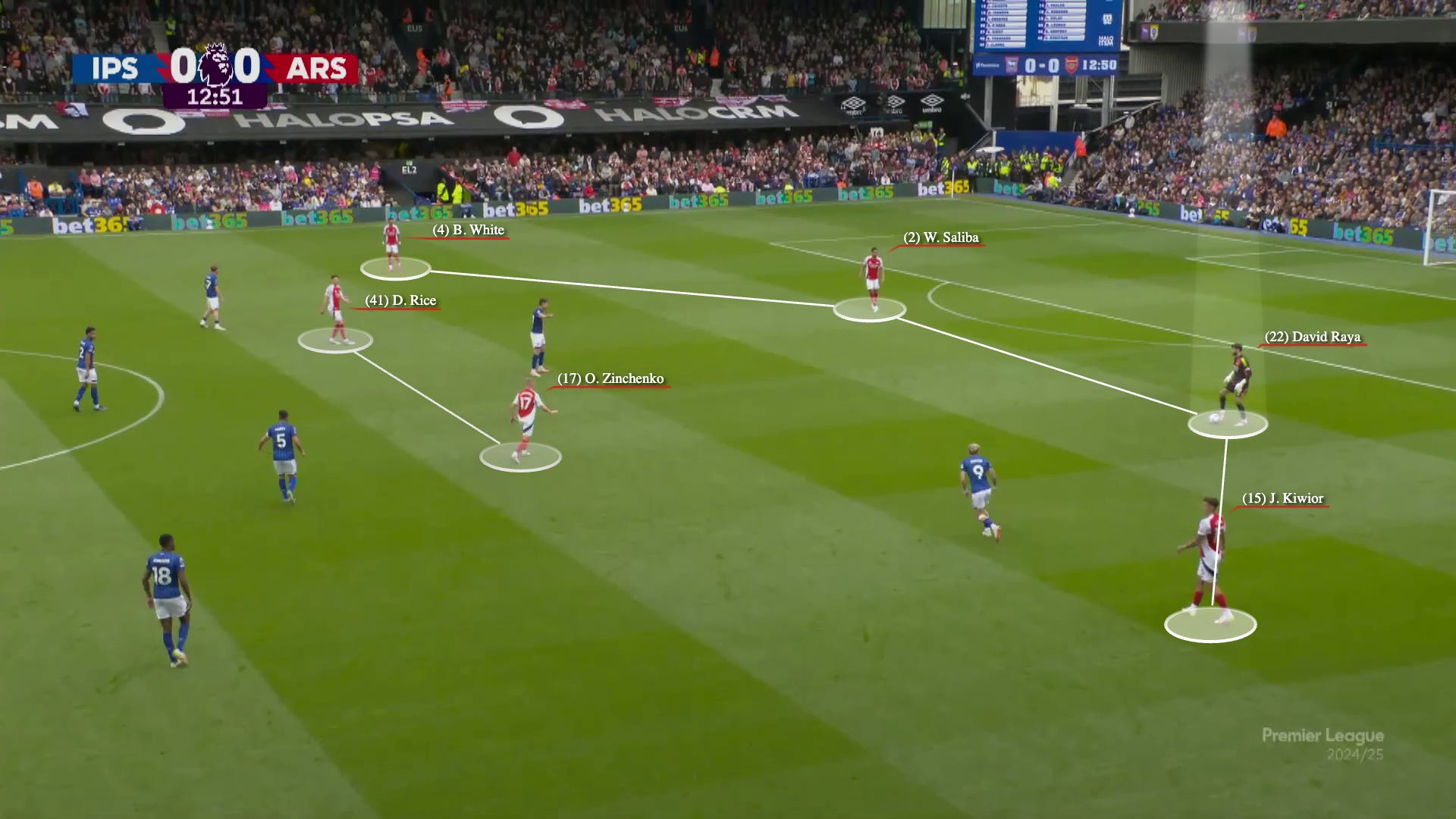

This strategy was not kept under wraps early. Within the first minute, with the opening chyron still on the screen, David Raya picked up the ball and the team unfurled out. We saw a typical “4-2” build-out shape, with Rice and Ødegaard in the pivot.

This “fill-in-the-blank” pairing, in which various partners rotated with Rice and Ødegaard joined in, contrasts with what we saw against Real Madrid. In that contest, there was a steadier pairing of Partey and Lewis-Skelly, designed to move around and manipulate the opposing front two.

Ipswich are generally well-coached, but some of their younger players are easier to exploit. Whereas the chief defensive problem of Real Madrid is the inconsistent effort of the front two (and Vázquez getting cooked at RB), Ipswich’s vulnerability is a little different: by rotating and doing unexpected things, you can probe their ability to communicate and cope. Often, you can push it to a breaking point.

Here, Ødegaard never received a pass. But by whipping behind Rice when the latter went to receive, Saliba was left free; Jack Clarke can’t close down because White is already galloping down the wing. Jens Cajuste throws his arms up in frustration.

White was moving things along in his typically subtle ways, and that triangle was humming again.

We also saw some more unexpected uses of the pivot, designed to confuse the young side. This moment started as a pretty typical look.

…but then Rice does something that you’d virtually never see Partey do from the #6 position: he backpedals high, all the way into the Ødegaard spot at high-RCM. Ødegaard then notices this and fills the gap, forming a pivot with Zinchenko.

Ødegaard drops, and the free man (Zinchenko) is easily found. Off to the races.

More than anything — more than pure quality on the ball or talent — this is about experienced players who know a system inside and out hammering home an advantage of pure technical know-how.

👉 What happens when you don’t track back?

There was a considerable advantage in terms of level of application, as well.

Arteta and I historically differ on one thing: I believe that fatigue has an outsize effect on final decision-making and ball-striking, and to offset that, I’d usually like to have nine outfield players sprint back for every single counter, and to have a slightly lighter ask of one attacker (generally, your best carrier/finisher). I’d never argue for a true passenger, just a slightly more opportunistic countering threat on the margins.

…and I wrote those two paragraphs last week, before seeing this.

“You can see the numbers,” said Mohamed Salah after securing the title. “Now I don't have to defend much. The tactics are quite different. I said 'as long as you rest me defensively I will provide offensively', so I am glad that I did. He listened a lot and you can see the numbers.”

“When you play in the Premier League you have to defend but I said that I can gamble and somehow I can make a difference. My number of assists shows that, you can create chances as well.”

But that’s Mo Fucking Salah is a fair retort, mind you.

One could also potentially argue that asking players like Havertz and Jesus to clatter into every duel and track all the way back could increase their injury risk; Jesus, after all, did go down at the edge of the defensive box. But that’s complicated.

Chelsea have problems on this front. Some of their core players just require too much from their teammates. The following frame was a full two seconds after Reece James was tackled. Madueke is still flat-footed, Enzo has his hands up, and Palmer is actually walking away from the play.

You can see that in the final moment, Enzo is probably a half second from closing down on Iwobi, who scores. If somebody made a slightly quicker reaction, that window probably closes.

The Premier League, getting more intense with every year, is increasingly ruthless about exploiting moments of inaction like this.

But it happens everywhere. Here’s Jude Bellingham (usually of relentless stamina and focus, and who I would have weighed for my #1 in the Ballon d'Or last year) reacting to a misplaced pass in the Copa del Rey final:

…and here’s Pedri hammering it home shortly after. Despite having a five-yard head start on him, Bellingham is still out of picture.

And this is why Arteta makes no such exceptions. He seemingly believes that offering players this leeway will seriously impact the team’s ability to contain defensive transitions. But he also likely believes that any walking can have a contagious effect to the team culture. “Everybody offers maximum effort, all the time” is a simpler message to convey than the alternative.

After getting put in the Arteta meat grinder last year, PSV coach Peter Bosz noticed the difference upon review.

“I learned a lot from Arsenal. Afterwards, I thought, ‘We played pretty well… but we lost 4-0?’ In the build-up, we did well and we had our position game, but as soon as we got to their box it was over. How is that possible?,” Bosz says.

“Me and my coaches studied them. What is it that they do differently to us? The answer is that they are outstanding in the opposition box but also their own. They get a lot of players behind the ball as soon as possible. They do it with 10 or 11 but we only did it with six or seven and then the distances are bigger. It’s the transition.

The more intense and transitional the highest levels get, the more evidence piles up in support of Arteta’s view.

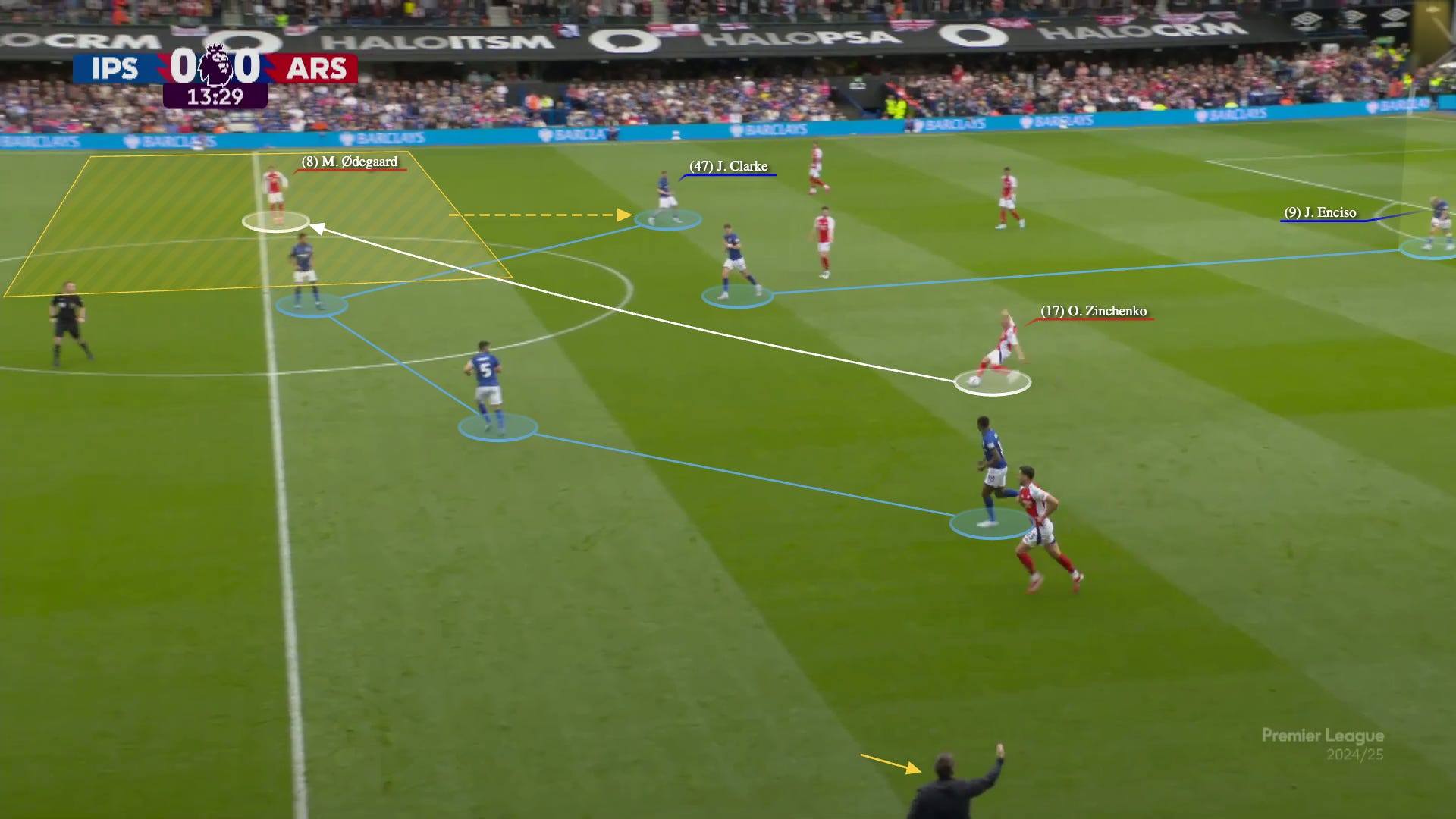

Right after that nice bit of Arsenal build-up, Zinchenko was over-ambitious and lost the ball, kicking off a transition the other way. Enciso even got around Rice, and a good opportunity presented itself.

Enciso, one of the more shot-happy players in the league (career: 4.38 shots per 90!), decided to play against type and lay it off to his striker. It was mistimed and Kiwior stepped in front of it. Normal stuff.

But the difference comes next. Enciso was frustrated and put his head in his hands.

Watch the bottom of the screen here, as a fiery Kieran McKenna spots the danger, and pleads with Enciso (who I like plenty) to make his way back into the play.

Ipswich should really just fall back at this point. But on the other side, Clarke doesn’t spot that the front pressure is a man light, and pushes up to his normal spot. McKenna, on the bottom of the screen, is still pleading with Enciso to rejoin the play. But Ødegaard has spotted the soft spot, and Zinchenko whips it over to him.

Ødegaard drives forward through the free zone, lays it off to Saka, and Trossard does Trossard things. Goal.

That’s also, by the way, a good example of why Saka and Ødegaard don’t rack up mutual goal contributions. That’s a prototypical run of play for them, and only Saka gets an assist there.

Ødegaard is generally miscast as a final-pass player. At his best, he is one of the most deadly pass-before-the-pass players around.

👉 It’s the physicality, dummy

Enciso himself experienced the difference this burst of initial application can make.

Here we see him trying to get away on the counter, before encountering a grown man.

Here, he received the ball off the top of the box after a regain. Before he’s done turning, he’s got Saka in front of him and two others collapsing on his sides.

That is prototypical counter-pressing. While it’s nothing groundbreaking, the whole thing is about reaction time: do players see a ball loss as a time to regroup and react, or as an automatic cue to initiate the press? As we saw in the Chelsea example, half a second makes a world of difference.

Here, Rice joined with one of his trademark hooks from the #6. Arsenal were simply winning the battles on the day.

As much as we’d like to chalk up the Ipswich performance to clever tactical tweaks, so much of it came down to two simple questions:

Who is playing?

How hard are they going?

Consider that your spoiler alert for the Crystal Palace section a little later.

👉 Trossard floating, Merino backfilling as #9

The rotation and manipulation kept paying dividends throughout the Ipswich game.

The central idea can be seen here. With Ødegaard dropping lower, and combining with his old batterymates Saka and White, Trossard also floated over as a bit of a seat-filling #10. In essence, this demonstrates the value of Arteta’s vision for the box-crashing LCM: when the striker vacates the middle, Merino is always there to invade behind.

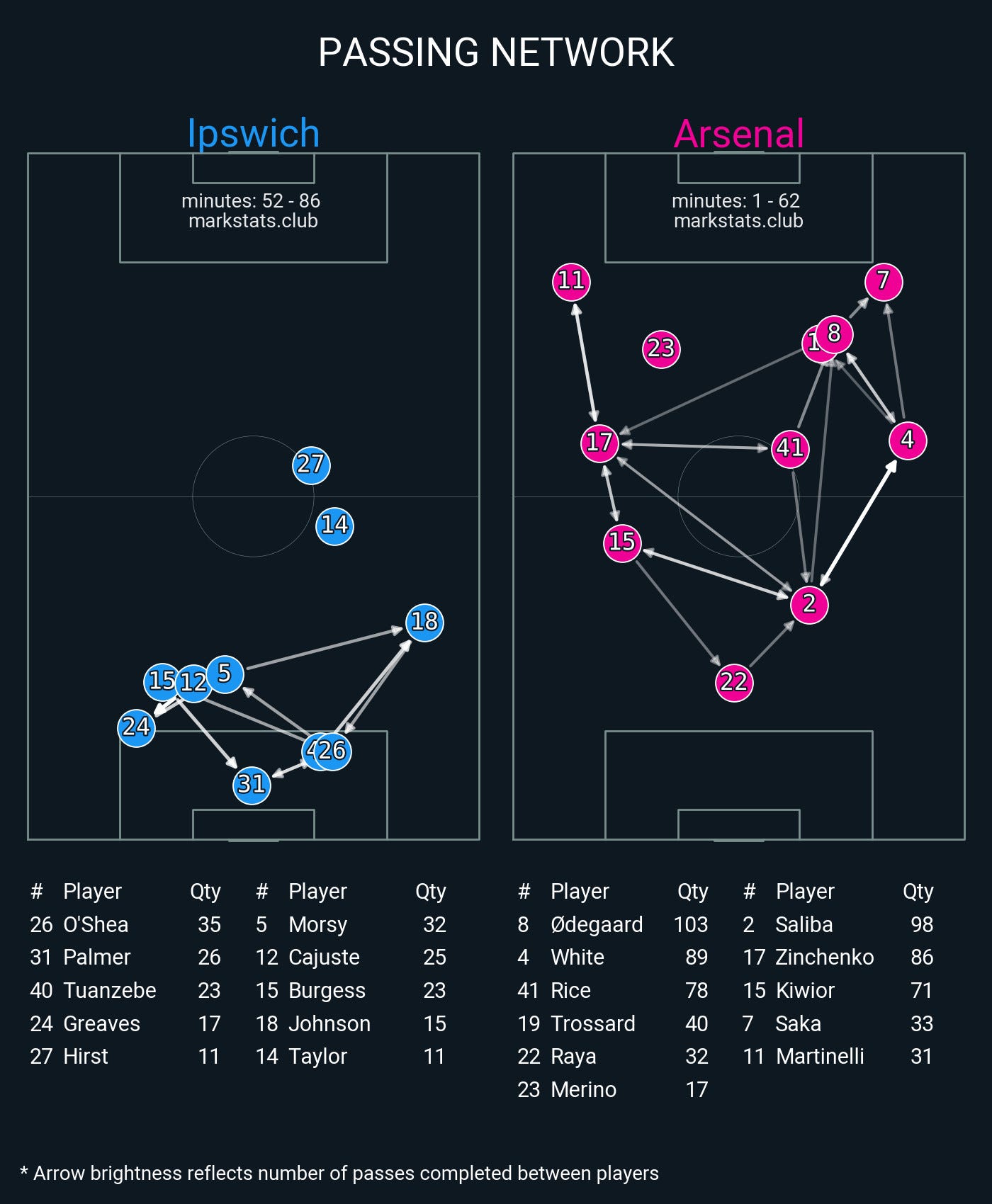

This is shown in the passmaps, where Trossard and Ødegaard’s average positions wound up right on top of each other. (Remember that’s just an average position over 62 minutes; it doesn’t mean they were actually in each other’s way, as you’ll often see suggested on maps like these.)

We saw this play out in the lead-up to the second goal. With Clarke overburdened on his left, Trossard drops down to receive in a spot usually associated with Ødegaard.

With Clarke discarded from the picture, Leif Davis is presented with a difficult choice: track Saka, or leave him behind and pressure Trossard. He eventually goes up to Trossard.

This causes the domino effect. The LCB (Greaves) has to rotate out, Saka beats him easily on pace, and crucially: there are numbers in the box, even though the striker isn’t there. Merino drives to the penalty spot and Cruyffs an assist.

It wasn’t long before Davis earned his red card on the wing.

Clarke was subbed off then. Enciso was subbed at half.

Some of these same advantages played out against Real Madrid.

👉 High advantages start low

Frustrations with the frontline are often misdirected. When it feels like a team is banging its head against the wall in the final third, it’s often because there simply isn’t space, and scoring without space is quite difficult, and space is often manufactured in earlier phases. The whole point of building from the back is the ability to arrive in the final third with advantages.

Against Real Madrid, there was a tangible advantage. The front two of Vini and Mbappé — who have a credible (if debatable) claim to being the two best players in the world — can be exploited in the press. Their shortcomings are often covered by pure effort from players like Bellingham, Valverde, Camavinga, and Modrić.

The Arsenal job was to put those “coverers” in untenable positions. Early on, Arsenal lined up in a simple version of the build-up shape. Whereas a parade of options would drop into the pivot against the likes of Ipswich, this was much more locked in: it was mostly a Partey/Lewis-Skelly tandem.

As Partey and Lewis-Skelly see-sawed around, Bellingham and Rodrgyo would pinch in to support them. Arsenal had a countermeasure ready from the whistle: whenever Bellingham and Rodrygo would wander too central, they’d swing out wide and get hit as the free man.

These free carries allowed Arsenal to arrive in the final third with advantages.

The swirling movements of Ødegaard, Partey, and Lewis-Skelly would disorient that midfield. Below, we see one of the arguments for Rice playing in this high-8 role: he can be found as the free man and given opportunities to power-carry, a situation a #6 is usually deprived of.

After that, Bellingham and Rodrygo got a little more spooked about Rice and Ødegaard, so they kept a closer watch on their movements in those 8 spots. This drew them further away from the midfield pivot, which gave Partey and Lewis-Skelly a little more space to operate.

…and Raya didn’t find it too difficult to find them between the pressers.

This happened for most of the tie. In one of the best recent displays of build-up prowess, Arsenal had gone up, back, down, and side-to-side before settling it onto Raya’s right foot. He set up his body-shape to fully sell a pass to Saliba and get Vini to cover that angle.

…and as soon as Vini is far enough along in his journey, Raya twists his plant foot and drills it up to Partey. Disguise:

And again Rice is found as the extra man, with green grass in front of him. This driving carry led to the third and final goal in the first leg.

All of those advantages started with successes in the build-up.

👉 Exploiting Real Madrid’s short blanket problem

In the preview, we noted how much hinged on the usage of Valverde:

Ancelotti has a classic “short blanket” problem, primarily based on how he uses Valverde. If he plays Valverde in midfield, it helps protect against the middle being overrun — but it leaves the flanks exposed.

In the first leg, Valverde was shuffled over to right-back to contain Martinelli, who looked electric in the previous contest.

It is no surprise, then, that Arsenal found joy through the middle. Both of those Declan Rice free-kicks were started by central dribbles against a tiring midfield with a 39-year-old in it.

Here was the setup to goal #1. Thank you, Bukayo.

And here was the setup to the second goal.

You have to get into dangerous areas to do dangerous things.

The second leg saw Valverde flip into the midfield, which meant that the primary advantage would be found at the full-back level.

In our preview, the top two keys to scoring against Real Madrid were as follows:

1. Pull the CBs into the midfield, time a run behind

2. Force backline communication

They are related, to be sure. Combing through successful attacks against Los Blancos, there were just so many situations like this that found joy for the opponent:

We saw both of those keys in the first goal of the second leg.

It all started with Raya going long and Merino getting contested by two Real Madrid players. This is your perfect flick-on situation, the kind of thing Brentford often engineered with Mbeumo running off Toney.

Saka sprinted out to retrieve the ball, and Rudiger went wide to cover him, forcing a backline switch and communication.

Crucially, then, Saka went to ghost through the line and Ødegaard pushed the advantage, hitting Rice through the middle — where space would be at a premium but where, like a bishop in the middle of the board, he has many moves available.

That’s where we saw both keys happen at the same time. Tchouaméni steps up to mark Merino, Raúl Asencio takes a step up, and Saka darts behind. Because of the rotations and unexpected movements, the Real Madrid backline isn’t in lockstep and Valverde kept Saka onside.

The final goal was because of physical application (and also a bit of ambition). This showcases two things to like about Merino: an ability to weight these perfectly, and a propensity to actually go for them. It would have been understandable to regroup and pass it around. But no:

Free from Valverde, Martinelli had a physical advantage on every other full-back that Real Madrid could offer.

👉 Three other keys

Aside from the obvious, there were a few other keys we identified as especially important for beating Real Madrid:

Forcing Bellingham to defend deeper so he couldn’t float and receive high, unlocking advantages through power-carries.

Nullifying Rodrygo’s ability to receive the ball in space. When he makes an impact, it shifts Madrid from a hero-ball team to a balanced attack.

Winning Zone 14 — which becomes a real concern if Rice is too high.

The first objective was largely satisfied by Bukayo Saka. This is why superstars are so important. Simply by being on the pitch, Saka pulled Bellingham down to help double him. It didn’t just improve Arsenal’s attack — it hurt Madrid’s. This is because phases aren’t separate. Bellingham had trouble getting free, carrying forward, and affecting play when tied down in this way. We’ve seen something similar before: when Arsenal’s wingers force players like Phil Foden to defend, it cuts off City’s rhythm at the source.

The second objective (stopping Rodrygo) was largely satisfied by Lewis-Skelly.

He still goes to ground too much, and will be put to a tall task against PSG. But it’s genuinely bewildering that an 18-year-old midfielder can now be trusted as a top wide 1v1 stopper in the final stages of the Champions League.

Two skills in particular stand out. First — and we shouldn’t underestimate this — he’s a lot faster than I thought he was in his youth days. He can simply keep up with the world’s top wingers.

Second is his reading of diagonals. These are notoriously tricky to defend, and while he made a mistake (on what shouldn’t have been a penalty) against Everton, this has generally looked like a strength — which is no small thing.

He is yet to be dribbled by in a Premier League game.

For all the opponents he’s faced at the senior level across competitions, he’s been dribbled by exactly one time: against Shakhtar.

The final thing to observe was the coverage of “Zone-14,” that spot on top of the box where so many promising attacks originate. There have been moments when this zone has been a little soft when Partey drops into the backline (think the Neto goal by Chelsea). This shows why I like Rice so much more as a “big-game #8” than an #8 against teams like Crystal Palace; because the opponent is more likely to sustain possession, Rice is more likely to be back here helping and doing what he’s best, instead of waiting in a high pocket like Merino may.

He was the best player on the pitch.

…and here was a little moment I liked. Look how quick his reaction is to a one-touch free-kick to get it around the wall.

The tactics, and the application, worked against Real Madrid.

They worked against Ipswich.

Why didn’t they work against Palace?

🤨 What failed against Palace

Against Palace, there were early, false signs that another romp was on.

Kiwior went to hand-check himself free into space on a set piece, but there was one problem: nobody was marking him in the first place.

But, alas, the lead was short-lived. The warning signs were early; struggling Ødegaard was back. He misplaced approximately zero (0) of these last year.

Eze had a great strike off a corner. Trossard and Sterling closed out a touch late, and in a pet peeve of mine, they spun and turned their backs on the ball. This was the exact kind of situation that we saw Rice closing out at the Bernabéu.

In the end, the formulas that cut through Real Madrid and dismantled Ipswich didn't apply against Crystal Palace.

Most importantly, Arsenal either faced knocks or rotated players:

Sterling was in for Saka

Merino was out, confirming a Partey/Rice/Ødegaard midfield

White was out again

There was no Havertz, Gabriel, Calafiori, Jesus, Tomiyasu, Jorginho, obvs

This has visible effects.

But the primary issue wasn’t tactical. It was a lack of intensity.

Of note:

Arsenal won just 16 of 40 defensive duels (40%) on the day. This was well below the season average of 61%; the overall duel count was lost 80 to 45. Without Merino, Havertz, or Jesus, we were particularly poor in the air, winning just 3 of 18 aerials (16.7%). Second balls were lost.

Arsenal had 235 more passes and 13% more possession than the season averages, but most of it went sideways. The team completed 386 lateral passes (more than double the season norm of 179), and created ten fewer penalty box touches than usual. Possession was “dominated,” but in a highly sterile way.

No aerial target, no pinning, no crossing threat. It’s not always a bad thing, but only two crosses were completed on the day.

There was little press to speak of. The drop-off in duel intensity allowed Palace to escape pressure and mount calculated counters.

😬

But they also met a well-coached stylistic mismatch.

For my money, Palace’s 5-4-1 (5-2-3?) setup offers the highest chance of defanging Arsenal’s attack. Arsenal are most comfortable out wide, and are less dominant centrally. This kind of shape clogs those wide areas by default. Full-backs are so key to Arsenal’s unlocking of teams, and back-fours usually mean that Arsenal can isolate them on wingers. A back-five can limit their ability to consistently impact the game.

There have been general frustrations against teams like Fulham, but to me, Arsenal have looked most toothless in games like this one at Newcastle.

…and this one at Old Trafford.

Against Ipswich, the reasons for success were unsurprising and layered. Ipswich tried to play. Their back four held shape but pushed up, with full-backs who stepped out and midfielders who chased shadows. It opened lanes for Arsenal to play through, especially with smart third-man movement between Ødegaard, Timber, and White.

Before he was signed, our Merino scouting report noted how important he was to cover certain qualities.

Merino is a really good off-ball presence, which has a lot of overlap with his brains and his work-rate. Like Havertz, he offers those selfless dragging runs, and is happy to sprint when there’s a switch to pull defenders away from his left-winger.

His false-9ing is weirdly good; here’s him serving as a backboard for a Spanish attack.

He’s also adept and active at feeling for pockets of space in the box, especially in bouncing ball situations.

[…]

I think it’s helpful to take a more expansive look at squad lists, and look less at “positional cover,” and more at “profile cover.” A player doesn’t need to slot in at the exact same position to effectively cover a starter; their qualities need to be covered, however. For instance, Jorginho and Zinchenko were essentially spelling each other last year … at different positions. If Saka misses time, Arsenal will be light on 1v1 gravity, dribbling, and playmaking — that needs to be offset somewhere, but it doesn’t necessarily have to be at RW. As such, Merino is great Rice cover, even if he never plays in the #6. With Jorginho and Partey in the squad, Arsenal are perilously light on midfield space-eaters. Without Rice, you feel bad about the physicality of a Jorginho/Ødegaard/Vieira midfield, for example. Merino basically fixes that. Jorginho/Ødegaard/Merino is all good, and so are some other permutations.

He is also, in his own way, Havertz cover. Especially down the line, it got hard to picture lineups without Havertz in them — especially when you’d like to go long or take advantage of set plays. Merino covers that, too. In many ways he’s the more practical version of what Arteta sought with Havertz last year.

We saw that against Ipswich. Trossard could vacate the #9 space, safe in the knowledge that someone would arrive to occupy the next zone.

There was superiority in athleticism, tempo, and tactical execution.

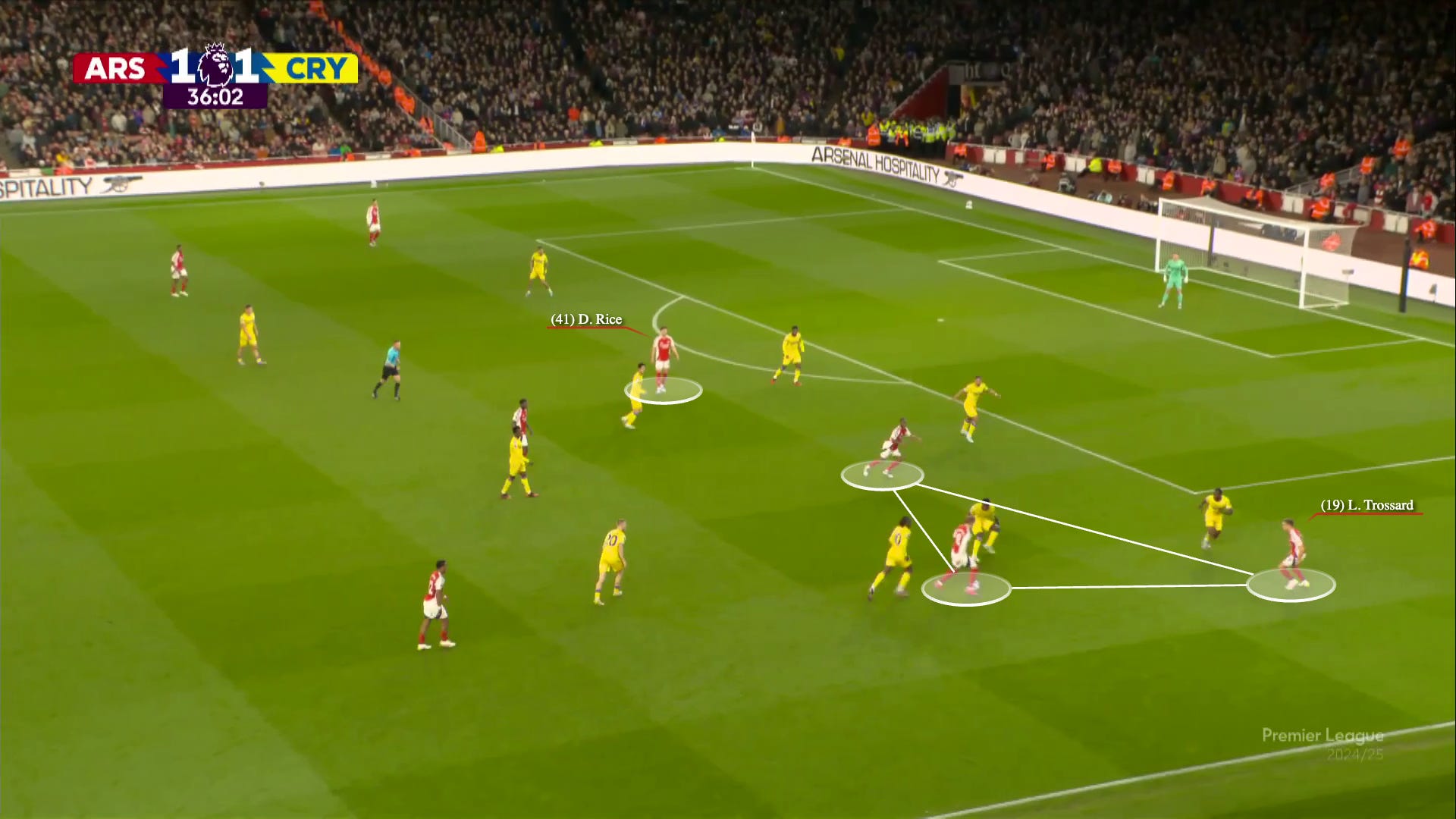

Palace was a different matchup — more athletic, more disciplined about staying put. And when Trossard saw fit to leave his spot, it was Rice (or no one) behind. Rice is just not as strikery as Merino in these situations, and less likely to gain advantage in the blind spot. He feels a little too high and off-ball for a game like this.

This defensive shape directly impacted Arsenal’s core attacking rhythm: spacing became tight, underlaps and wide rotations were smothered by sheer numbers, and individual duels were fought in traffic. The Ødegaard-White-Saka triangle that normally manipulates the right side became Ødegaard-Timber-Sterling, a clear downgrade.

And without Saka, there was no gravity. Sterling, needless to say, doesn’t pin defenders the same way, doesn’t force the same reactive movements, and isn’t consistently combining. The natural progression that pulls a back-four or even a 5-4-1 into asymmetry was absent.

My preferred way to attack a back-five is to use the 10s to drag around the wide CBs, then attack the space behind. We saw that in the last matchup against Palace, in which Merino was able to magnet players away from the middle, and Jesus was able to do a prototypical striker run in behind.

This resulted in one of five goals.

On Wednesday night, the lack of movement allowed Palace to hold a static line without overcommitting. The rotations still happened, but they were mostly in front of the block. Timber would make efforts, Ødegaard would drift, but there were no real consistent breakthroughs. In the absence of Saka’s gravity and Merino’s box presence, there was a hole where dynamic forward play should have been.

The result was a passing network full of horizontal recycling: Kiwior to Saliba, back to Kiwior, maybe out to Timber, then back again. See.

Some wild stats came out of that:

Against Real Madrid, Kiwior and Saliba exchanged two passes

Against Crystal Palace, they exchanged 96

Against Crystal Palace, Saliba attempted 136 lateral passes alone

In reality, the game looked like this.

Passes between CBs are not inherently bad. But there is virtually nothing happening here. Saliba and Kiwior are not actually probing the line or moving anyone around; they’re just dinking it back and forth. Nobody else is actively looking to get on the ball.

In the end, Palace also took advantage of Arsenal’s risky rest-defending setup, and pounced on a Saliba mistake. From my end, that one doesn’t require too much analysis. I think Saliba just screwed up, and Mateta had a genius moment.

Structurally, though, Rice played too high for my liking.

I still have some concerns about the load placed on Ødegaard as a low receiver in the build-up and a high-engager in the press. Those two responsibilities are far away, and not only will it lead to a lot of running this year, it can lead to situations where the press can’t reset after a ball loss. As effective as a dropper as he is, I hope there are some different options there.

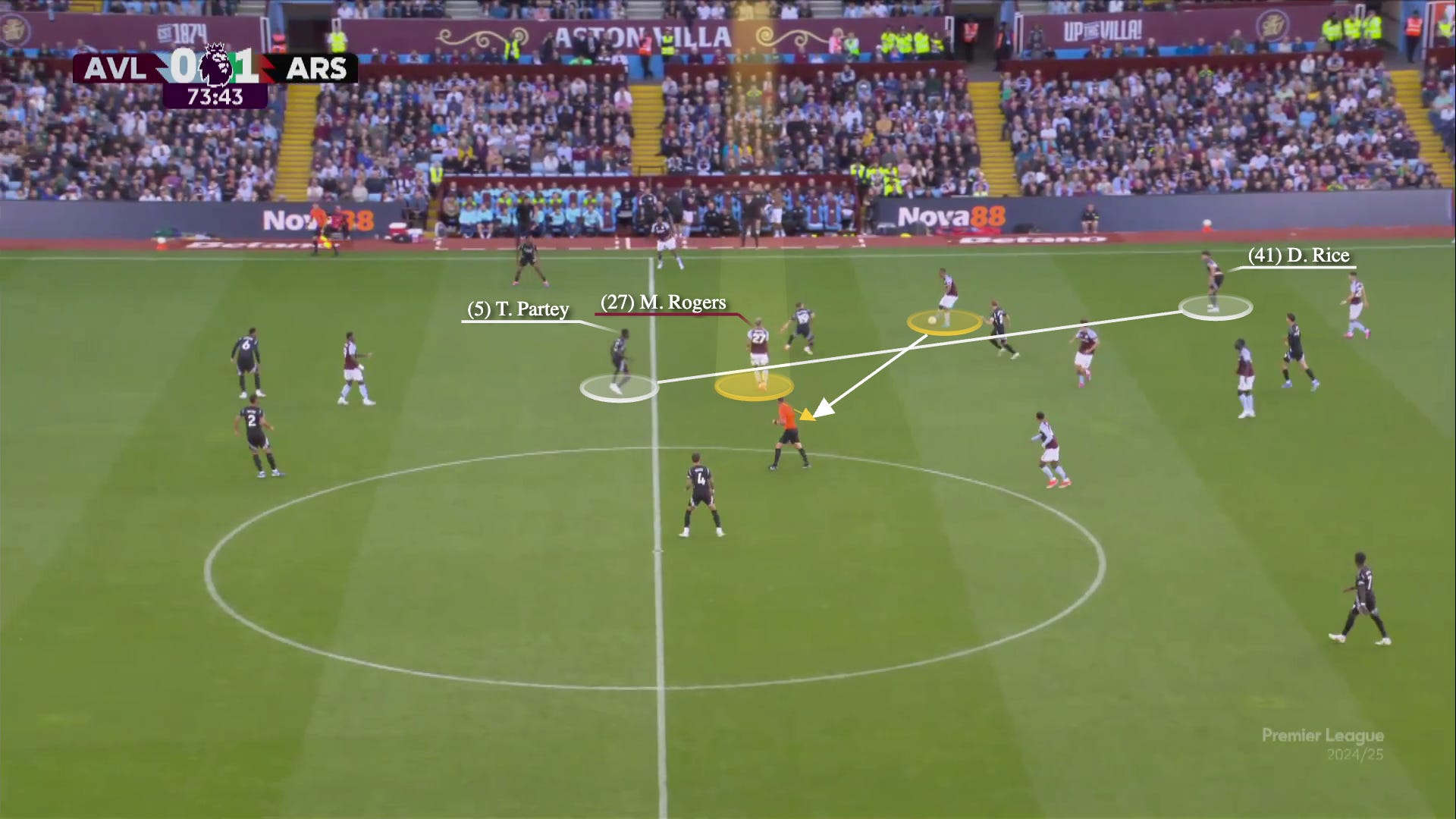

In the first match against Villa, we complained about how those Morgan Rogers counters all originated with Rice out of the frame.

There are a few factors in play here:

Ødegaard dropping next to Rice at #6, like we saw against Ipswich, still makes sense to me. Ødegaard is devastating when he has the chance to pick apart overmatched teams who press a bit; there aren’t even that many chances to uncork our own press, so the distances aren’t too big of a trade-off. The only real reason not to do it is to manage his fatigue.

Rice playing “high” against teams like Real Madrid is much more acceptable (and preferable) because Madrid are more likely to have sustained stretches of possession, meaning Rice naturally ends up deeper anyway as Arsenal shift into a block. His instincts and range are so valuable when he's screening passes and cutting out carries at the top of the box.

I keep feeling like a “4-1-4-1” blocking structure should be used more in certain situations, so the highest level of pressing can be more readily done by Rice or Ødegaard, depending on where they fall.

I’d expect Ødegaard to drop a fair amount against PSG, but ultimately, he will be roaming in that high-right pocket like he did against Real Madrid.

👉 MLS in the #6

As we wrap up, I’d be remiss not to mention that Lewis-Skelly made his senior debut in the deepest midfield position. I would have assumed that he’d roll into the #8, so that was interesting.

I wanted to check in on two things. The arguments against MLS playing in this spot would be that a) he’d have to sit too much, and b) he may be too aggressive about intervening defensively (instead of blocking lanes and holding space as required).

We got one little glimpse here where he clamped an attack, squeezing it down before diving in. He had ample coverage, but the instincts looked good.

Arteta talks about “good height” and you can see how high Lewis-Skelly was willing to go immediately. He wasn’t playing like a pure coverage #6; he was playing against ten men, and wanted goals, whatever his position.

Our other sixes are more likely to be a few steps back. Lewis-Skelly combines through the middle and gets a shot off.

Fascinating player, that.

🔥 Final thoughts ahead of PSG

Arsenal have engineered a squad to take down the best. The club has signed bullies, pressers, space-eaters, and cross-claimers: Rice, Havertz, Timber, Merino, Raya, Calafiori. And it works, but there are limitations when:

a) those players are unavailable

b) they’re not able to play at their highest levels of intensity, or

c) mid-table opponents formulate a game plan where those advantages are dulled

The last three matches carried some interesting context for what’s ahead against PSG. Against Real Madrid, Arsenal showed how clarity and discipline could frustrate a team of attacking outliers. Against Ipswich, it was about overwhelming a physically (and tactically) overmatched opponent with speed and movement; those rotations could be useful on Tuesday. And against Palace, Arsenal got a reminder about the costs of under-intensity. PSG will blend some pieces of all three.

Here’s an annoying screenshot, that also speaks to the job that Arteta and the remaining players have done:

My general feeling is that the pressing and midfield battle is where this tie will be decided (though there is still an opportunity to hit the ball behind their full-backs upon a regain). PSG will look to have a lot of the ball, but will also look to turn every loose touch into a transition moment.

Last time, Arsenal went all-out in the press — in Paris, and throughout the 90’. With a likely midfield of Rice/Merino/Ødegaard, that should happen again. Dial it up to the maximum.

Donnarumma can be “got” and others, who are press-resistant, could still be susceptible to some shoulder-to-shoulder contact.

The question becomes whether to go fully man-to-man and risk Kiwior getting left alone on Dembélé (or others) if and when Saliba pushes up. There is risk there, but my feeling is “fuck it, we ride,” especially in the first leg. If you don’t do that, the forward press doesn’t have quite enough edge.

Having Merino available becomes critical — not just for his size and set-piece threat, but for his ability to match the running, manipulate the space, and win the duels. Without him, the midfield loses some bite and resilience, and Arsenal would be betting on technical quality alone to get through the press. With him, Arsenal can match (and hopefully better) PSG’s volume and intensity, which keeps the game on Arsenal’s terms. We can also properly backfill the #9 area when Trossard floats.

I don’t expect many tactical surprises; both teams have clear identities. PSG will also press high, try to dominate and rotate on the wings, switch to isolate, gobble up as much possession as they can, and use quick strikes when the ball turns over; they might be the most devastating attack-force in Europe. They will likely try to create goals like the last one Salah scored at the Emirates: bursting quickly into the area vacated behind Lewis-Skelly, isolating Kiwior in space.

Their rotations mean they may be vulnerable on the counter, and they can definitely be guilty of playing basketball. Arsenal withstanding the inevitable attack, then countering quickly, has a high chance for joy.

Arsenal will have to be clean and inventive when playing out. This team generally performs well against back-four, pressing teams, because it’s what the squad was built to do; the full-backs swirling around as free men can catch the press out. I wouldn’t necessarily go with Lewis-Skelly as a default pivot from left-back, but a more rotational cast (including Merino and, yes, Ødegaard, but within reason). Because PSG don’t have a prototypical “sitting” defensive midfielder, you want to play into those impulses and move them around as much as possible.

Rice can be expected to be awfully secure in that pivot, but we’ll see if he needs support to make it more incisive. The build-up needs to feel like sensory overload to PSG (long, short, rotations, safety, line-cutters). There should be opportunities for bursting full-back carries; we saw John McGinn drive all the way up the pitch and score in a similar situation.

It’s obvious that we’ll have to be careful with turnovers, and ruthless when chances appear. Martinelli should get a few chances with Hakimi up the pitch. It’s also obvious that it’s about executing better — more intense off-ball work, smarter movement in possession, sharper decision-making when the moments come. The margins will be smaller than against Ipswich, Palace, and even this iteration of Real Madrid, and PSG will punish mistakes others can’t.

Perhaps the biggest advantages for Arsenal are on set pieces and aerials. Those should be exploited to a maximum. My gameplan is thus: take the nerds, and bash them.

PSG don’t offer some of the “under-detailedness” (or the out-of-possession passengers) of Real Madrid. It’ll be about who applies their plan better for longer, and who imposes themselves in the battles that matter most — midfield duels, second balls, lack of mistakes, and the transitions that define matchups at this level.

Arsenal were built for the big ones. PSG are in top form in 2025, and are built to score against anyone. The difference will come from intensity, sharpness, and a few inches of space either won or lost.

Three matches left to make history.

Another great one, Billy. Extraordinarily clean writing too. This team deserves all the good in the world, just hope they are good enough on the day to grab it.

Manifesting a Saka hattrick as hard as I can but shitting bricks for the next 23 hours so see you on the other side :)

Dunno why this made me more nervous for the PSG game but we move