How to attack Liverpool

It's Anfield Eve. Let's look at a few ways for Arsenal to score against the beleaguered yet dangerous side

Last the two met, Arsenal beat Liverpool 3-2 in a thrilling contest that is still one of my fondest memories of the season. Watching Arteta scream at his defenders to protect the lead in the closing minutes by playing further upfield against a tired opponent, all within earshot of Jürgen Klopp, felt less like a simple footballing moment and more like the passing of an invisible baton.

Back then, I shared a big preview which covered the hangover that Liverpool was experiencing (perhaps not dissimilar to the hangover I’m nursing as I type this), and what they were doing to get back on their feet (it’s eggs and electrolytes for me). The Reds looked plenty dangerous in that one, and afterwards, I wrote a piece entitled “How Tomiyasu and Xhaka joined forces to pocket Salah and disrupt Liverpool's attack,” a deep-dive on how Xhaka dropped low to negate Salah, particularly early.

Much has changed; much hasn’t. Klopp still faces many of the same problems. (Truth be told, he still creates a few of the same problems, as well.) Despite some flourishes of the old, dominant form — particularly at Anfield — the stubborn quandaries persist.

The season has been plagued by a fundamental design flaw. By initially looking to transition from a false-9 to a classic striker profile in Darwin Núñez, they essentially pulled one player out of the advanced midfield, which increased the portfolio size of the midfielders who remain. When that is combined with a midfield that is either injured, aging, or dropping off a cliff for much of the year (Fabinho) — and a strange decision to never reinforce what remains — that means Liverpool can simultaneously look too stretched or too compact, and struggle for control.

This impacts everything: the settled defending, the press-resistance, and their own famous capacity to press (they’re 13th at tackles in the attacking third, with 2.18/90). Salah has to play a little further from goal; Alexander-Arnold’s role has shifted; Mané is at Bayern; et al.

There have been changes. Klopp has moved to a more mid 4-4-2 block, Núñez is now shuffled to the wing, and Fabinho’s performances have alternated mid-highs and lows (instead of pure lows). Still, it can feel like trying to defy gravity, and Klopp seemingly can’t help but continue throwing huge numbers of players forward on set pieces and the like, despite the evidence.

The season has also called into focus the incredible burden that is placed on Virgil van Dijk when they are playing well, and how exposed they look when he looks more ordinary. Whereas he used to calmly snuff out dangerous moments as a solo act on Virgil Island, a lot more communication is needed these days, and it hasn’t gone well.

This all has had multiple knock-on effects, including an increased set of responsibilities for the full-backs, who are increasingly targeted and generally more restrained from being their vibrant, attacking selves.

Or it’s simpler than that. Maybe it’s this: their play-style requires superhuman stamina, and this year, they look a little tired.

Here are some ideas on how to attack them at Anfield. Since we’ve already gone in silly depth this week, consider this more of a side dish than a main course.

1. Force communication and hand-offs with wide triangles and diamonds

When looking to score against Liverpool, a good rule of thumb is that you want to force as much communication as possible, particularly as the game rolls on. This is for two reasons. First, they can be late at recognizing rotations. Next, their recovery speeds are not at previous levels.

On the Arsenal side, here’s what we wrote earlier this week, which I’ll re-share in full:

When firing on all cylinders, this Arsenal team can combine what you see from the most disciplined positional teams with what you may see from a Real Madrid in a Champions League game.

On one hand, the motive behind positional set-ups is to enable players to play with more flexibility and creativity, because they always have a sense of where their teammates will be. You’ll hear guidelines that make that possible (“no more than 3 players in a horizontal zone,” “no more than 2 players in a vertical zone”), but I see Arsenal breaking those rules pretty regularly.

That’s when they play like Madrid. At times, as you saw against Liverpool, it can feel like Ancelotti’s advanced tactics are to put three or four of the best players in the world around a half-space, and ask them to do whatever they think will score a goal; they can feel under-coached in the best possible way.

There’s a reason this has been so effective, so filled with moments of brilliance, but prone to occasional inconsistency in league. If you’re able to combine the relentless buzzsaw tactics of good positional play, with a little more combo-laden simple entrepreneurialism of tip-top players when things need a jolt, you have a mighty concoction. Jesus and Trossard naturally provide that. Increasingly, others are joining the party.

In the comments section, u/facelesspk pointed us to a long-read called “What is Relationism?” Over the course of the season, you may have heard me drop references to Hamilton’s work, and particularly use “relationism” to describe some sequences of Arsenal’s play. But I hadn’t yet read that one from late-March. I’m now glad I have —it looks like a near-definitive guide to me, and I’d encourage you to read it.

Now, to speak to the Real Madrid example specifically, no team offers a better recent template after bouncing them from the Champions League 6-2 on aggregate, which concluded with six unanswered goals.

How did they do it? Through transitions. Through forcing mistakes. But most repeatably, through the toco y me voy and tabelas on the edge of the box.

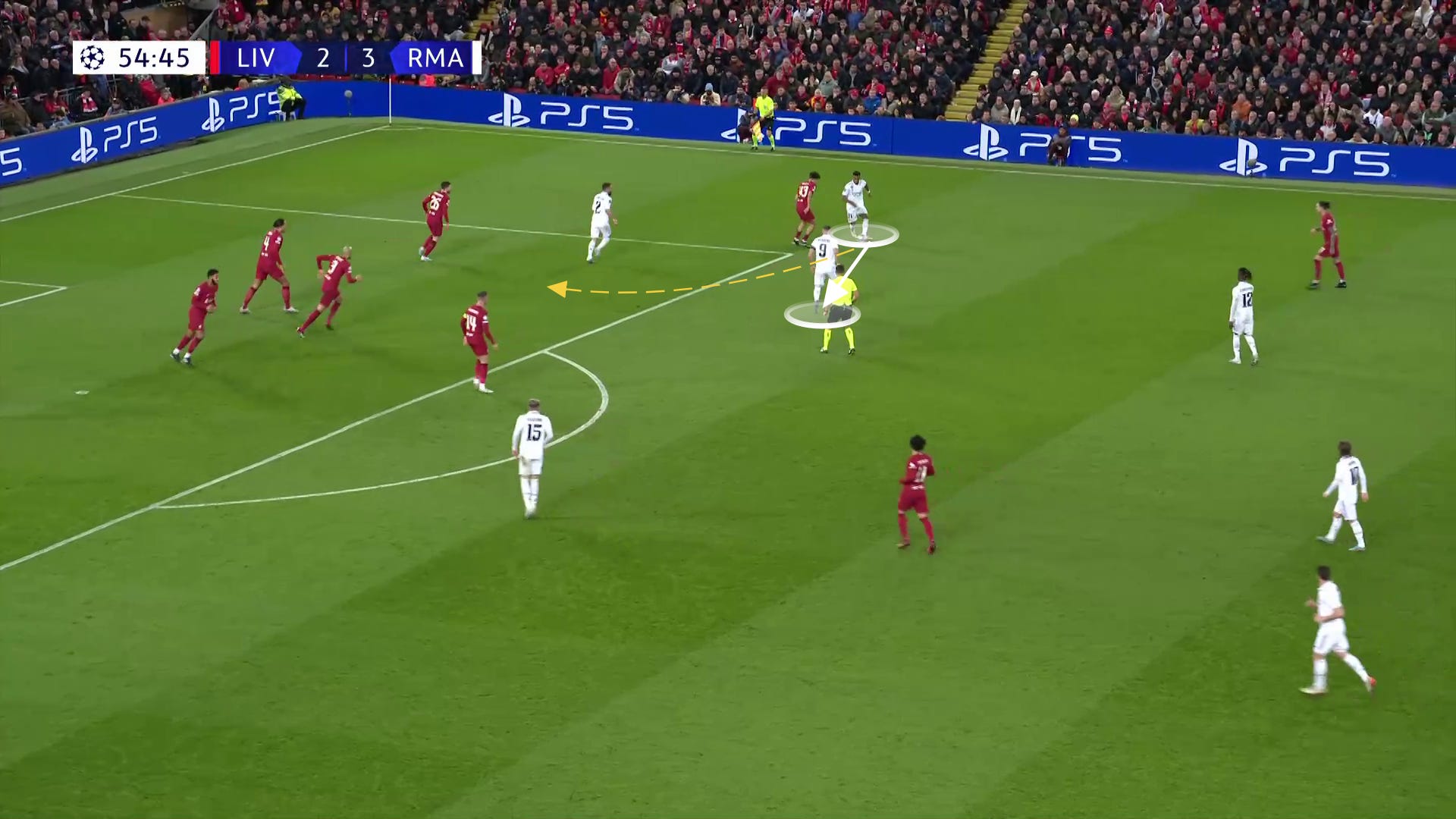

Down 2-0, Vinicius accepts it at the corner of the box. Benzema is behind him, and three others create a diamond. Henderson is doing his best to disrupt the play:

But Vinicius dribbles, cuts, and lays it off to Benzema. With Salah now down here helping out, Benzema flicks it to Vinicius and starts cutting around towards the goal. This will naturally put defenders like Henderson on guard:

So Henderson switches off Vinicius and goes to track Benzema as he cuts, thinking Vinicius is covered with the protection in the box. This gives Vinicius the little crease he needs to fire a shot into the corner of the net.

As much as that’s just a great individual effort, this is a pattern: rotations and 1-2’s causing slow Liverpool feet, creating little openings for shots to come off.

Later in the same game, Real Madrid has already come all the way back, up 3-2. There’s a bouncing ball that leads to a duel between Curtis Jones and Carvajal. Carvajal regains it, passes it out to Rodrygo, who starts a new triangle with Benzema, this time on the right:

With Carvajal underlapping, Rodrygo drags the ball up and dishes it to Benzema — then sprints to create a give-and-go into the box. This pulls Fabinho out, but if you look, this is still a 3-on-6:

Rodrygo plays it back to Benzema, who finds another gap between the closing defenders, and hits a deflected ball into the net to make it 4-2:

Finally, here’s an example from the 4-1 Manchester City win, in which Julián Álvarez played a key role.

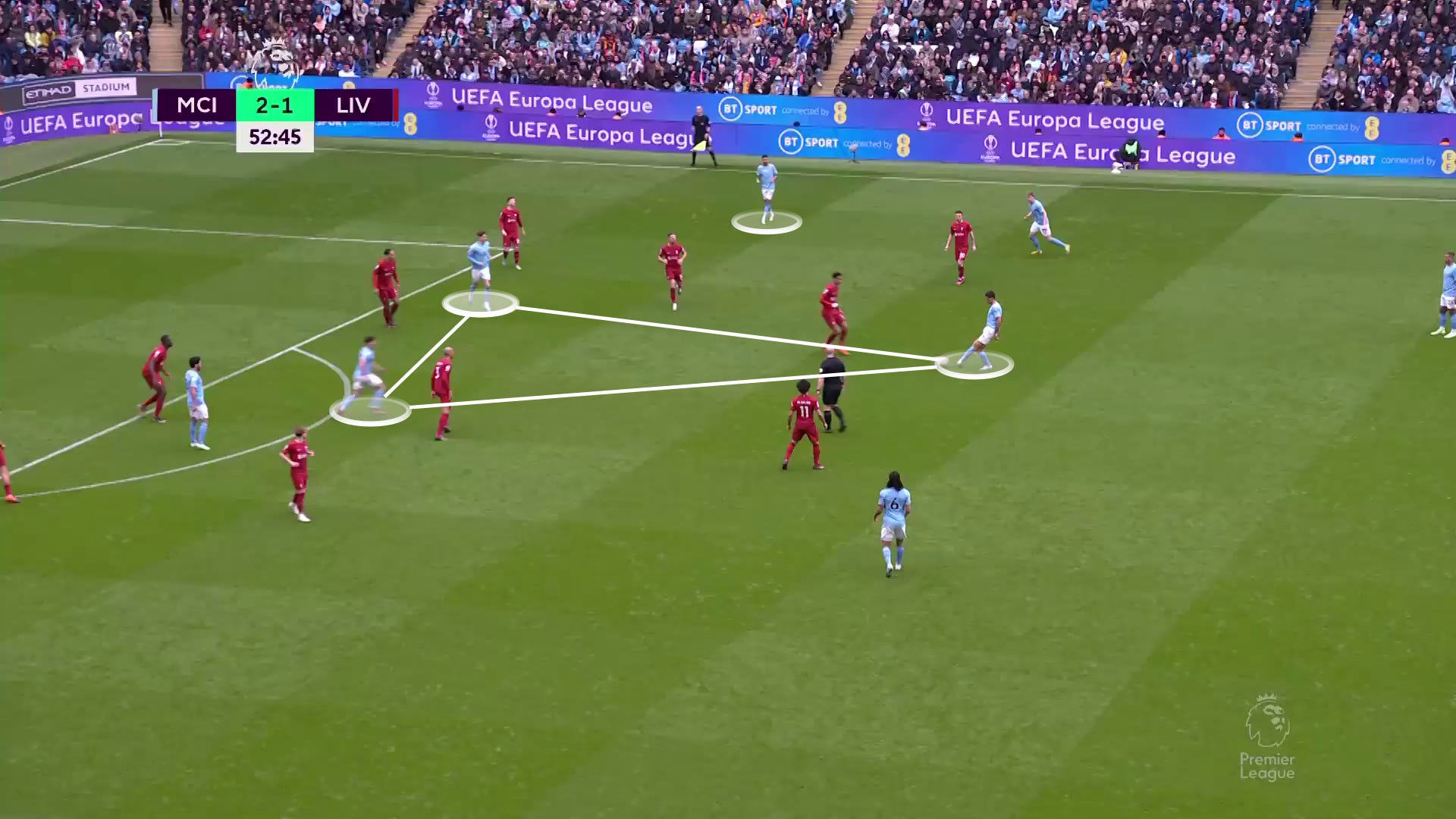

Rodri plays it to Álvarez, who is dropping from the front-line to form a triangle with Rodri and Stones (in the channel). Álvarez lays it off for Stones, who gives it right back:

Now, Álvarez has the ball much higher and plays it to Mahrez, who will find desirable attacking possibilities out here on the wing. Meanwhile, Álvarez sprints back to the box to maintain pressure:

As Mahrez dribbles towards the goal, Álvarez is never really picked back up by Fabinho. He winds up with an acre of space in front. Look how far part the centre-backs are, with no Fabinho filling the void:

Álvarez eventually rips a shot, which spills into Gundogan’s lap, who scores.

A particular strength of Arsenal’s — these quick, well-drilled movements on the corner of the box — is a particular weakness of Liverpool’s. They are often caught flat-footed, particularly as the minutes accrue.

2. The hold-up 9 ➡️ winger connection

Speaking of Álvarez, you’ll see another pattern here: Liverpool seem particularly vulnerable to false-9’s. This is because it further pressures the midfield, and in turn, makes the job even harder on the centre-halves: they have to decide whether to hold the line, push up against a winger in the wide areas, follow the false-9, stay back, etc. Álvarez was an expert at exploiting this.

With the game tied 1-1, Alexander-Arnold was drawn upfield like the old days, so Man City pushed the ball up quickly.

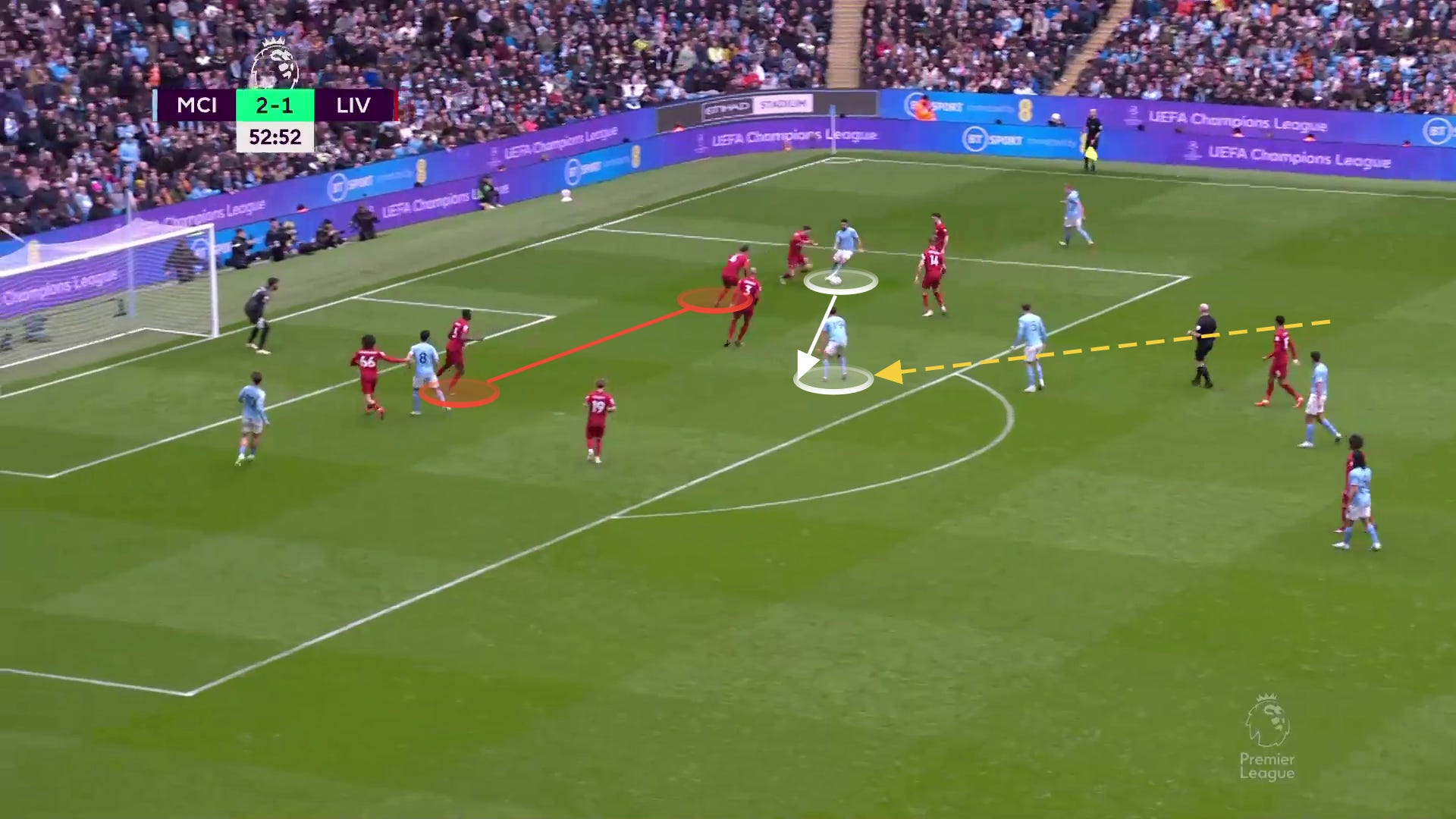

As soon as Álvarez got it, he banged a perfect curling through-ball to Mahrez. Man City wingers were extremely disciplined about holding width throughout, to maximize the amount of space that the Liverpool CB’s had to cover. Look where they’re caught here, as TAA struggles to get back into frame:

Mahrez had pretty easy work from there to make it 2-1.

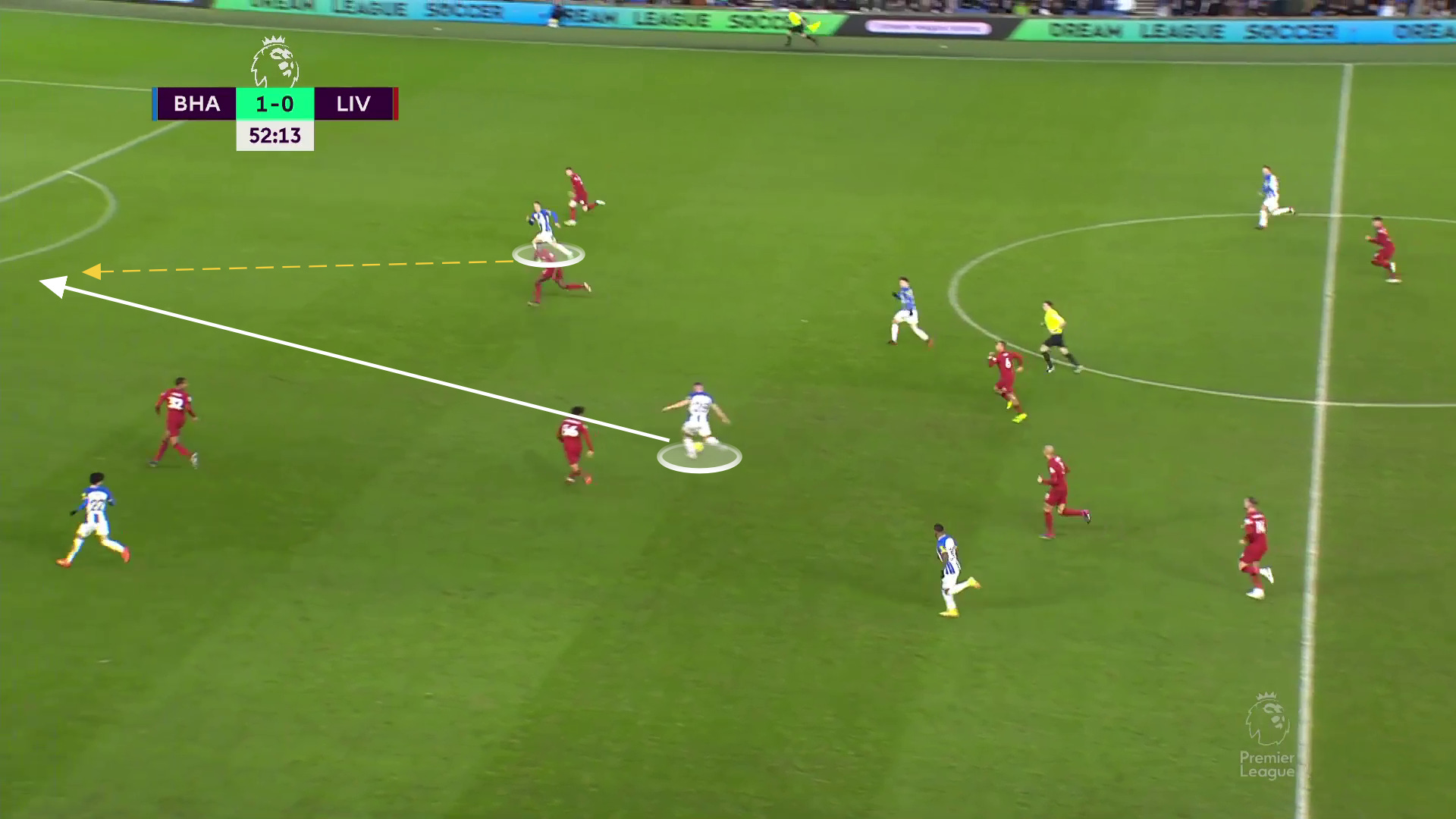

Similarly, in the Brighton game, Estupiñán won a second ball — another good time to keep the pressure up on Liverpool — and shoveled it to Evan Ferguson, who is downright silly for his age. He hits a diagonal-cutting March, who exploits the space and scores from the box:

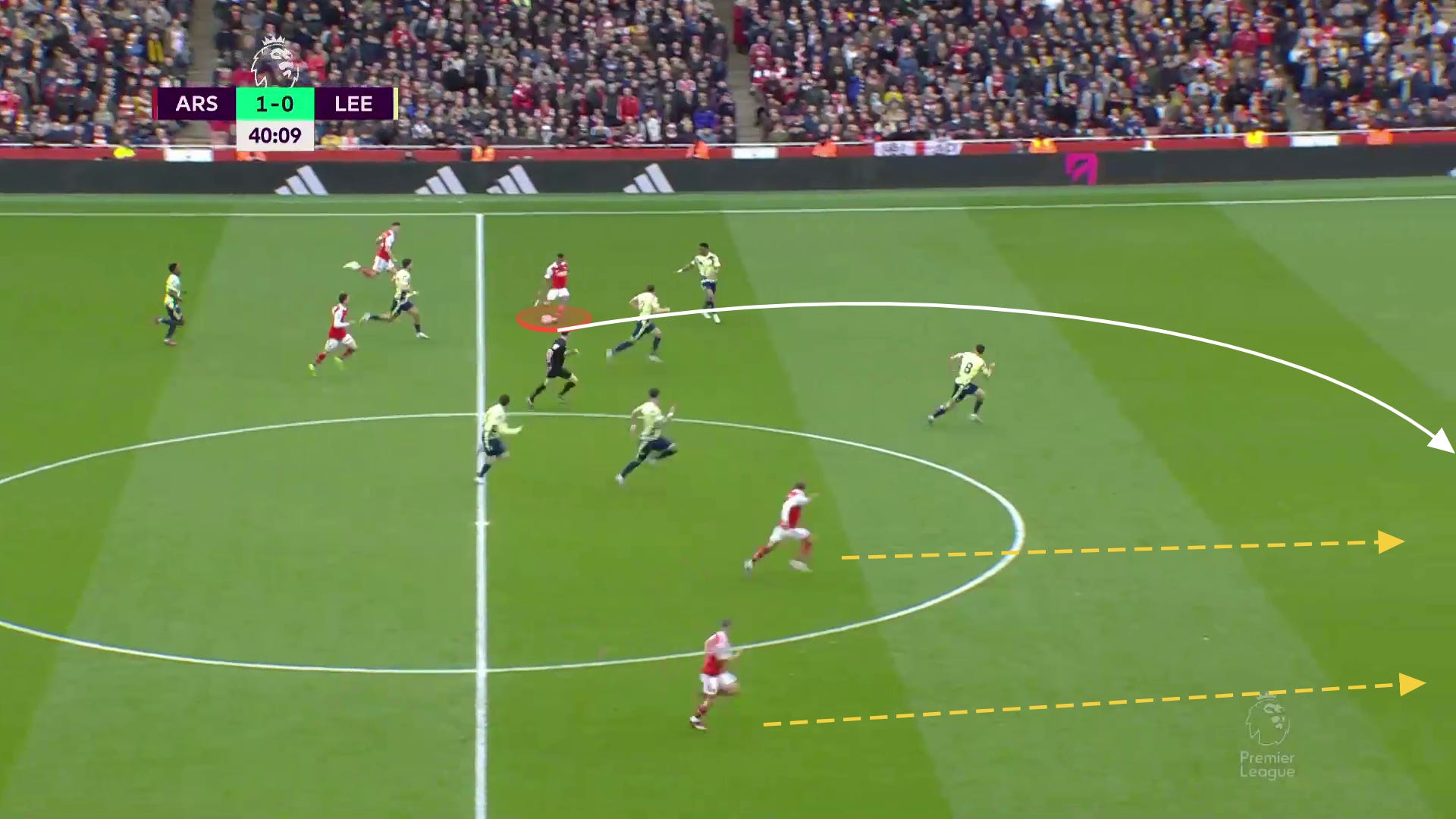

Jesus had a near-miss on one of these in a post-corner moment against Leeds:

Regardless of the Liverpool gameplan, there should be more opportunities in transition than Arsenal tends to get. Real Madrid attacked them with ruthless efficiency, and I’ll continue my quest to figure out how to get Martinelli in a Vini-like defensive position in the block (Vini is often just standing at the half-line, waiting for a transition opportunity to strike. That’s not in line with the overarching Arsenal philosophy, but I’d love to see more of those Ødegaard-to-Martinelli balls like we saw against Brighton).

When these opportunities present themselves — particularly after a counter-press, or set piece (when Liverpool pushes a lot of players up) — the objective is first to spread them out as much as possible, then to maximize the interactions between Liverpool defenders, either by diagonal, cross-zonal runs, by dragging defenders around, or by maintaining width until the last moment, as Grealish did several times:

Looks a lot like that Martinelli opener at the Emirates, no?

Speaking of holding width…

3. Ødegaard and company dragging defenders into place

In many ways, the Arsenal build-up shape looks purpose-built to exploit a midfield like Liverpool’s. Not only are the credited midfielders a strong trio (Ødegaard, Partey, Xhaka), Arsenal also has three other players who add to those numbers: Zinchenko, White, and, crucially for this fixture, a dropping 9 (likely Jesus, potentially Trossard).

Broadly speaking, as Man City showed, Arsenal should make sure to have attackers holding width on both touchlines throughout. Against a jumpy, aggressive opponent, often with with light numbers and recovery speed in the midfield, you want to maximize the opportunity for lanes to open. That means there should be rotational coverage for Martinelli when he freelances inward, and it also means that Saka should stay pinned and not be too involved in build-up.

Looking through the tape, there’s a particular rotation in build-up that may pay dividends. If Liverpool continues pushing forward in a mid-block 4-4-2, a lot will depend on White working in a back 3-2-5. If he’s able to induce pressure from the left-winger, Ødegaard can then run out to the touchline, and Jesus can drop deep to back-fill the position and maintain the “box midfield.” From there you have “double width” with Ødegaard, and a lot of exciting opportunities to play it forward:

This also has the likelihood of isolating Jesus (or Trossard) on Fabinho (if he plays), which is a rough one for Liverpool — Fabinho’s “game lag” challenges are likely to result in fouls against some of the more unpredictable tight dribblers around.

A situation like this took place early in the Manchester City game.

Guardiola’s side is building up in a 3-“box”-3, with Liverpool in a compact 4-4-2 mid-block, looking to pack in the midfield to disrupt straightforward play there. There are currently 6 Liverpool players “in the play” here:

Once Akanji receives it, that’s a trigger for the winger (Jota) to move up and pressure him, looking more like the high 4-3-3 of old. KDB swings down to give Akanji an angle in addition to Stones:

…and KDB, who is followed by both Henderson and Robertson, splits it up to Mahrez, who was holding width up at the wing. Because the ball travels faster than the man, all six of the Liverpool players we highlighted above are essentially taken out of the play. It’s off to the races here, 4v3 already:

Mahrez dribbled it through the middle, generated confusion, and as we covered above, Grealish stayed wide until the last moment to make the decisive pass for the goal.

4. Switches to the wing in general

Lastly, and perhaps most obviously after reading this, is the switch to the winger. Liverpool has a tendency to lean heavily to the ball-side, particularly after throw-ins or when there are recoveries to be had. Teams have been able to switch the balls into space, which get the full-backs isolated in bad situations.

Take a look at how far the CB’s lean here against Man City:

From there, Alexander-Arnold is all by himself in a 2v1, the type of situation that puts him under the microscope. While it’s true he’s not a lockdown defender, it’s also true that he’s regularly thrown into scenarios where you think I dunno, whattayawant a guy to do here?. Konaté is still struggling to get back into the play, despite his pace. KDB cuts under:

…and because of how far he was away, Konaté never catches up to fully challenge KDB, who lays it off to Grealish for the fourth goal:

Those positions (a winger starting as wide as possible at the half-line before eventually working in) are a recurring theme.

🔥 In conclusion

Liverpool is a high-variance side. You know this, but let’s review: in the last month, they’ve lost to Wolves 3-0, beat Newcastle 2-0, got knocked out of the Champions League 6-2 on aggregate, beat United 7-0, lost to Bournemouth 1-0, and looked like they’d given up at the Etihad. You know, as teams do.

The variance is baked into this season’s cake. They give up high-percentage opportunities to their opponents, but have the best keeper in the league (world?) to clean things up — his PSxG+/- of +11.1 is best in the league ... by ~6 goals. They can be devastatingly clinical: against United, their seven goals were on 2.8 xG, which you can attribute to variance or a proclivity to Bangers. I choose the latter in this case. Despite the issues of their press, they still lead the league in recoveries per 90 (with 58). With so much of their play dictated by the last few percentage points of effort, the crowd at Anfield can often give them the final push they need.

Moreover, they have two potential targets for disruption in Zinchenko and Holding. In Zinchenko’s case, his contributions as a midfield controller can usually dwarf any issues in tracking through-balls; I expect Xhaka to drop back and help him, as he did with Tomiyasu, perhaps all the way back to the line, with Martinelli also in the picture. You simply trade a couple dozen dangerous moments in attack for a couple dangerous moments (total) the other way.

If Saliba is still ailing, Holding has four things on his side, and they each have names: Gabriel, Partey, White, and Ramsdale. I don’t think White has an obligation to plant himself too far forward here; as we saw in the tape, you don’t always need numbers in the box to score against Liverpool; some quick 1-2 work with Saka, Jesus, and Ødegaard can be plenty dangerous. He can still pin attackers and pick his spots for overlaps like usual, and if that means he manages his energy, and Holding doesn’t have to swing all the way over to the touchline to track wingers, all the better.

(Perhaps this qualifies as a #hottake, but there is an “in case of emergency, break open glass” option if Holding’s play is physical and looking “orange,” which is White at CB, Partey at RB, and Jorginho at 6. They all know everywhere to be on a football pitch, and match up well here. Arteta wrapped up the Palace game with the final two in those slots, without particular pressure to do so. It’s not as FIFA-y armchair radical as it first sounds.)

That’s all expectation management, however, as almost everything else is in Arsenal’s column. Make no mistake: at the moment, this is a mismatch, and Arteta’s boys have every reason to roll in confident.

We didn’t cover every possible way to score. The clearest is a simple midfield overrun. Other than that, set pieces will loom large, as well as Arsenal’s ability to counter-press the counter-pressers, particularly Fabinho.

But we did go over a few possibilities, including:

Forming tight, “relationist” 1-2 combinations on the edge of the box

Using the dropping 9 to play it out to the wingers in space

Dragging the defenders with Ødegaard and Jesus in standard build-up

Switching to wingers in general

I think Zinchenko’s role will hover over events, and add an altogether different element than last time. If you haven’t guessed by now, I’d lean towards starting Jesus here — there is a bigger opportunity than usual for a dropping 9 in build-up play, and he ranks among the world’s best at that. Trossard can slot in anywhere across the line ASAP in the second half after Jesus runs ‘em ragged.

I wouldn’t be surprised by some lineup surprises from Liverpool, who look desperate to change things up. Fabinho, in particular, looks like he’ll be in for a tough go.

For the life of me, I can’t keep these short, even when hungover. I’m gonna just stop typing now.

These are the stakes we were hoping for.

Did someone say steaks?

Happy grilling.

🔥