Inflection point

Taking a magnifying glass to see what actually went wrong in the second half against Villa, with observations on lineups, distances, strikers, Zinchenko, and much more. Then, we Bayern.

“There's a fine line between fishing and just standing on the shore like an idiot.”

— Stephen Wright

Well, that was disappointing.

But now is not the time for long preambles. With Villa behind us and Bayern looming, it’s time to try and understand what happened — and see where we go from here.

Join me.

☝️ Arsenal in the first half

With fourth-place Aston Villa on the menu, the lineups offered a mild surprise.

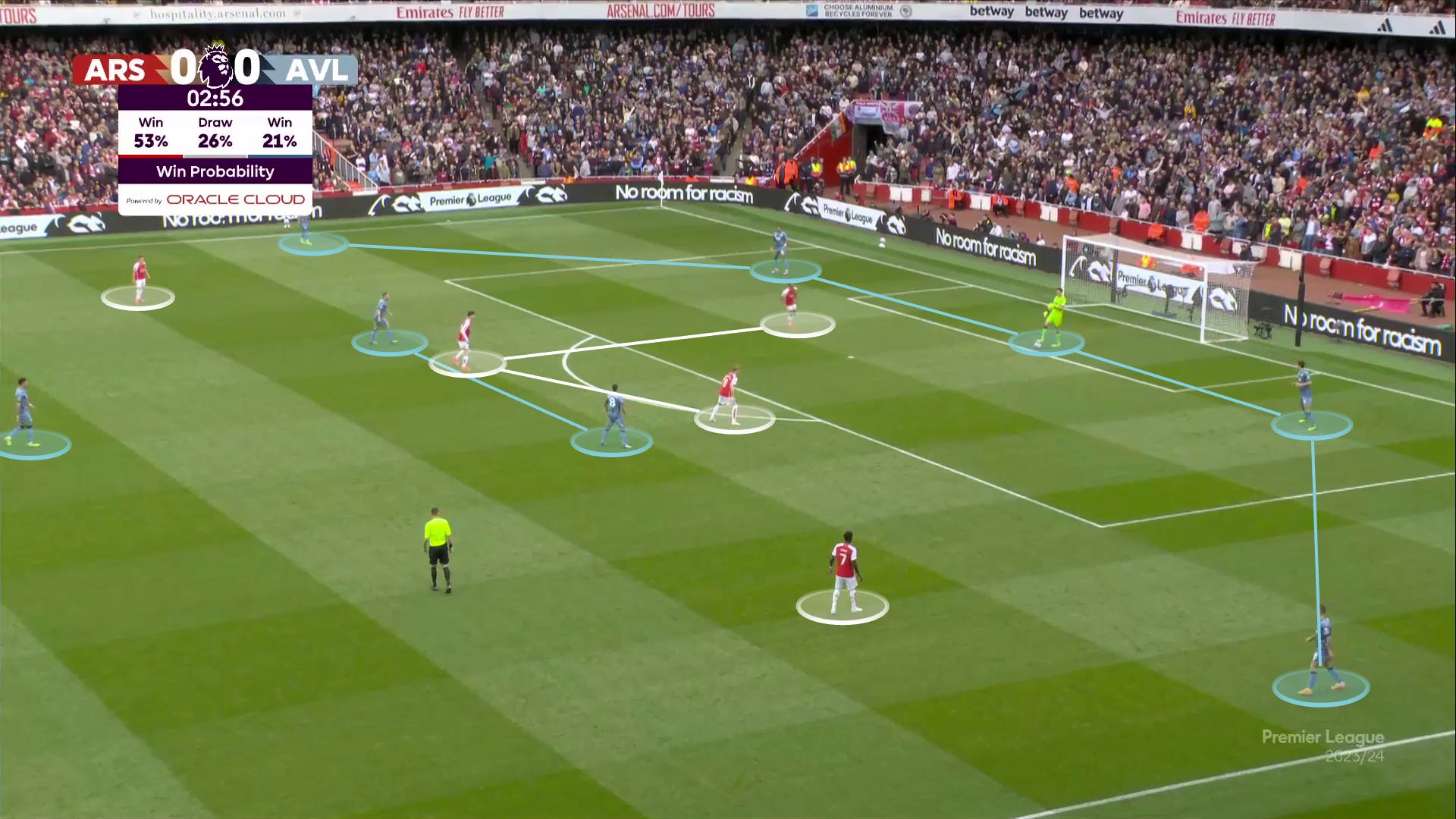

The majority of the game would look something like this.

For Arsenal, there has been a bit of rotation in the squad of late. Headed into this one, the team had yet to lose (or even trail) in the Premier League in 2024, topping almost every conceivable metric.

Here’s a look at those 11 matches in which Arsenal outscored opponents 38-2. I’ve also included the starters in four of the more heavily-rotated positions for reference:

Palace (5-0): Zinchenko LB, Havertz LCM/SS, Rice #6, Jesus #9

Forest (2-0): Zinchenko LB, ESR LCM, Rice #6, Jesus #9

Liverpool (3-1): Zinchenko LB, Jorginho LCM, Rice #6, Havertz #9

West Ham (6-0): Kiwior LB, Havertz LCM/SS, Rice #6, Trossard #9

Burnley (5-0): Kiwior LB, Havertz LCM/SS, Rice #6, Trossard #9

Newcastle (4-1): Kiwior LB, Rice LCM, Jorginho #6, Havertz #9

Sheffield United (6-0): Kiwior LB, Rice LCM, Jorginho #6, Havertz #9

Brentford (2-0): Kiwior LB, Rice LCM, Jorginho #6, Havertz #9

Manchester City (0-0): Kiwior LB, Rice LCM, Jorginho #6, Havertz #9

Luton (2-0): Zinchenko LB, ESR LCM, Partey #6, Havertz #9

Brighton (3-0): Zinchenko LB, Rice LCM, Jorginho #6, Havertz #9

In between, Kiwior got the big starts against Porto and Bayern Munich.

Looking through that list was helpful for me. While it may be presumed that Arsenal had settled upon a specific means for domination since Dubai, and that’s probably true in the biggest-game lineup choice, the reality is that the improvement (and consistency) has extended across a series of lineups and game styles. While the Havertz exploits and goals at striker have been the rage lately, the team had also outscored opponents 16-0 when he started at LCM/SS this year. We may all have our preferred set-ups, but it requires a bit of nuance. For one, I’m not sure Jorginho should start every couple of days.

Just two weeks ago I’d angled for some more Havertz and Jesus in front:

I still hold stocks in these two as a partnership up top, depending on the matchup. They're just so complementary in their movements, pressing, and on-ball/off-ball impulses.

We’d only gotten fleeting views into this relationship, which was likely a primary plan for the year until injuries got involved. There were times when you could see some of their unique potential: they just have great brains for association.

Facing a team like Aston Villa, there is a specific toolbox you want available. The short version is that you want passers and runners. Starting Zinchenko, Havertz, and Jesus makes a lot of sense in this regard; omitting Martinelli probably doesn’t, but I just can’t speak with too much confidence about the opaque world of player fitness.

Why does this matchup require these profiles? You may remember How to Make a Mid-Block Mid, my piece on breaking down the kind of shape that has troubled Arsenal in entanglements against Lens, Chelsea, Fulham, and Porto.

Here was the little diagram I created to show an effective mid-block:

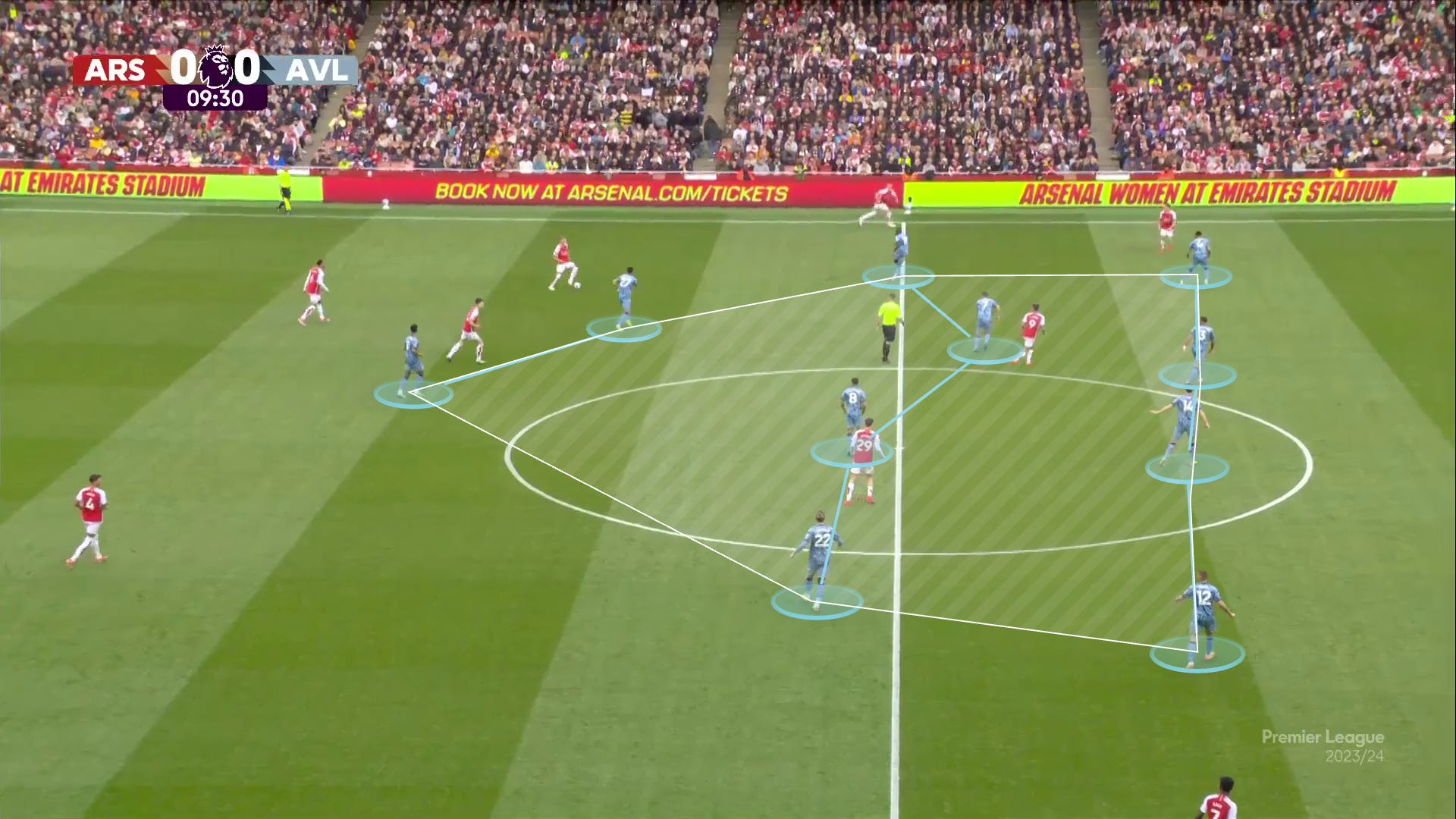

…and here’s what Villa looked like on Sunday. It was a platonic ideal, hues and all.

They are one of the most committed mid-high-blockiest teams around.

As I did my prep for the game, I essentially had two overriding thoughts about Villa:

Man, their absentee list is long: Luiz, Kamara, Buendia, Ramsey, Mings. Sporting underphysical CBs (who have been bullied in the box and on corners) and no DM, Arsenal had a real chance to overrun things.

Man, their expected “back-6” was going to be good on the ball. The press trigger was to be … Digne, I guess? And he’s a Barcelona full-back.

I may have overrated the impact of the first factor, and underrated the second.

👍 That good stuff

Arsenal would look to develop goals through the chance creation methods we outlined in the aforementioned piece.

Here’s the oversimplified TL;DR of what should be done against an out-of-possession side like this, at least according to the idiot you are now reading:

Attract a lean a switch quickly

Devise unexpected ways to exploit the space between the backline and keeper

Have the widest player drop deeper to receive, then exploit the space behind

Slip through the middle

Get bold with the CB’s

Arsenal basically checked every box in the first half. Arteta agreed:

“We’re really disappointed and frustrated because of the way we played the first half and the amount of chances and situations we created, how dominant we were and it should have obviously been a very, very different scoreline.”

The passing — difficult to execute and requiring high levels of timing, touch, and technicality — was largely executed by Ødegaard and Zinchenko.

The strategy was generally to have fewer players pin the backline — usually just three — with Havertz picking his moments to exploit their desire to hold steady by gathering steam on sprints in behind. This would give his front-marker (McGinn) a choice of whether to follow him (and risk opening space in the middle) or stay put (and risk letting him get in). For the CBs, it’s harder to keep up with a player already at pace than if they start from flat feet against the backline.

The offside trap is Villa’s largest defender, and they’re well-drilled in maintaining its integrity. Havertz himself can be known to go a step early.

Still, there was ample threat created on both the left and right in this period, which isn’t something you can say about every Arsenal performance.

In moments like the below, Havertz flashed the clearest example of what Arteta likely envisioned for him when signing him to play him in this role.

On the right — and, honestly, just about everywhere else — it was an Ødegaard clinic. Not only did he draw defenders together with his little dips and feints, he made several bigger-space line-breakers like this.

…and here’s an even “bigger” one: an expertly laid ball that used the same strategy as we saw before with Havertz. By this point, McGinn is sagging out of the middle to keep an eye on Havertz, which opens up space in the middle for Ødegaard and others to sink into.

The captain also threw some of these in for good effect. This looks like a scene from the spy movies where the hapless henchmen take each other out.

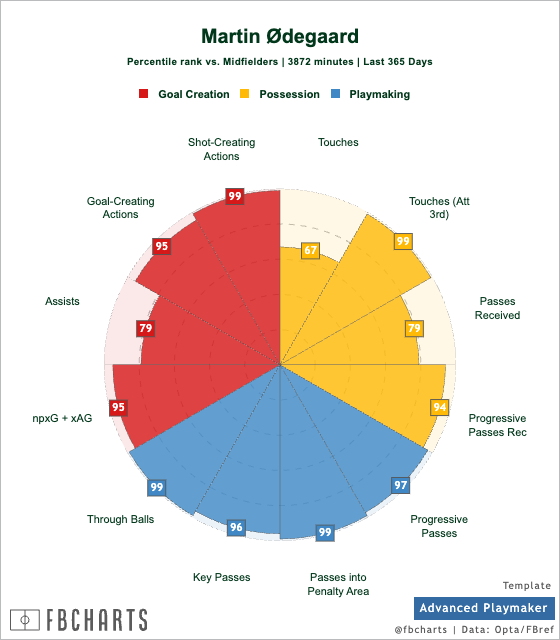

Ødegaard’s evolution as a passer continues, and some of that bigger stuff continues to get refined. The idea that he’s just about dips and tricks is an outdated one. He now leads all of Europe’s “top-5” leagues in through-balls, passes into the penalty area, and live-ball shot-creating actions. He’s third in progressive passes, behind Xhaka and Rodri, which is especially impressive given the locations he occupies compared to those two. Here’s what it all looks like in the last year.

That little triangle (high RB, Saka tucked into the half-space, and Ødegaard below them) continues to be incredibly hard to defend. The team wound up sustaining 57% possession and 14 shots in the first half.

But it was not perfect, and the goals never came. Despite the bristling pace and forward thrust, a few tangible opportunities were simply missed. The most notable one was a Trossard tap-in that we’ve seen him hit several times already: Jesus did a great job of driving this forward, getting Ødegaard’s rebound, and laying this on a plate.

But it was more than that.

🧮 The striker equation

Beneath the surface, a couple of subtle warning signs started to build.

The first was the “bonus striker” equation. This is easy to understand: by turning a full-back (Zinchenko) into a midfielder, you can turn a midfielder (Havertz) into an extra forward. The resulting dynamic wasn’t bad, but it didn’t necessarily capture the real complementary power of a potent duo, as we saw at Luton in December.

In the fifth minute, Saka goes for a cut-back and overhits it — but Jesus and Havertz were making the same run anyway, so it was unlikely to get hit in any case.

That happened a couple of times, and I wouldn’t expect it to be a recurring issue with them — it felt like two players reacquainting themselves with the other’s tendencies.

But there were other questions about their spacing and distance. At 15’, Jesus was dropping a little to help with build-up. Havertz was completely on his own when he received the ball in behind. To some extent, that’s expected: Havertz is now the striker. But what if there’s a deflection, rebound, or delay in the attack?

The same happened below, which is the expectation when you run a single striker. But this may not be capturing the benefits of running with two. If you watch Inter, for example, you may see Lautaro Martínez making a marauding run to the right here while Thuram holds it up like this.

It’s probably more readily captured here. Ødegaard does some nice work deep, Havertz runs through the middle and delivers a ball to Jesus, who surveys his options.

Jesus waits for the play to develop and delivers it out to Saka.

This is the moment of maximum danger. Saka is 1v1 and White is overlapping. But Ødegaard — that 15-goal cleanup crew of a year ago — was helping deep, so he is far away from the play. Havertz was only a level on top of him. Jesus held up the play.

The result? No one is left to attack the box. The progression just involved too many players.

This is not on any one player. It’s more on the underlying structure to require fewer players deep an more players forward.

Messi walks a lot; all of football involves trade-offs. My frustration with earlier iterations of the “Havertz at LCM/SS” thing is that the trade-off (he can’t pass like Xhaka) was not balanced with the reward (he wasn’t treated enough like a bonus target man, or peppered with far-post crosses, or used in twin-striker runs in transition).

Here, Havertz was treated more like a striker than my previous critiques would indicate. That said, Jesus was caught in the middle, structurally: he wasn’t quite enough of a midfielder (he was low-touch, only completing 13 passes) or a striker (he wasn’t always forward on these attacks, though he often was). With a goal-scorer now deep (Ødegaard), and Trossard at left-wing not being a pure outlet presence, it was too hard for this XI to generate its luck.

In sum, the final equation for this should result in 1.5-2 strikers. Against Villa, it often resulted in 0 (both players dropping deep) or 1 (Havertz lonely in transition). When it was two — which, to be fair, it often was — their runs weren’t always complementary enough to turn into goals (which would come with time).

A lot of this, I feel, is short-term. Jesus is clearly managing his sprints — he is toughing it through an injury — and the associative play of two top associators has a nice peak. I will always be a Jesus Stan.

If Arsenal play similarly against Bayern (but with a more negative setup, and a defensive full-back at LB), there should be less running overall, and some long-ball opportunities (especially from Raya). When the moment arrives, it’ll be key for both to bomb forward and capture the real advantages of starting an extra attacker in midfield — or, shall I say, “midfield.”

🤬 Villa have their say

The wheels came off in the second half. We will lurch for tactical explanations for why this was, but I found the loss to be intensely human. The energy levels dropped, and those margins were exploited by talented, disciplined, stubborn players.

Right after the game, I rewatched a 20-minute spell in the second half where things were especially listless, with an eye toward what Unai Emery changed in his setup to make it so. I found very little. I was happy to see this tweet from James Benge which confirmed that I wasn’t losing my mind (or, at least, not for this reason).

“Emery says he didn't change anything at HT, he puts Villa's success down to Arsenal not being as effective as they were in the 1st half (though he does praise Zaniolo for his work on long balls).”

The simplest way to look at the loss was in the inability to sustain possession.

You can also see it in the stark contrast of the overall passing numbers.

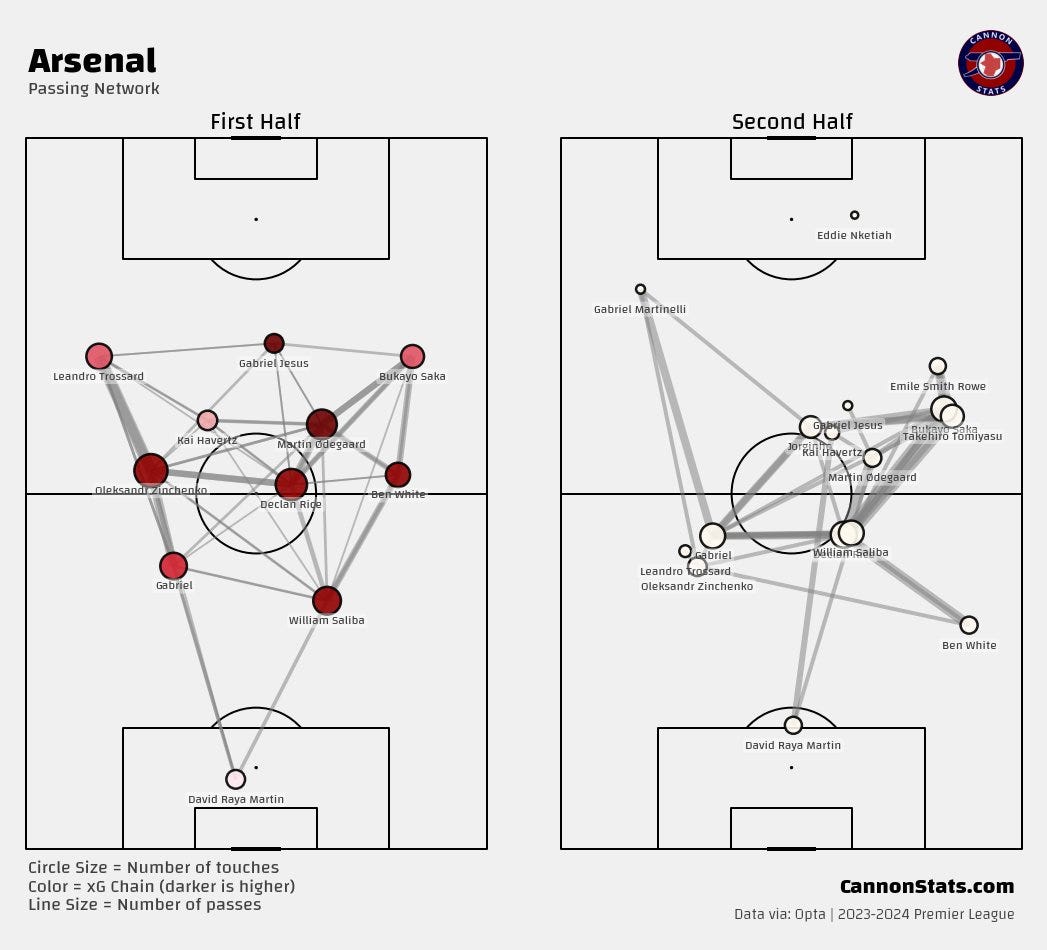

Probably most stark is this passing map from Scott over at Cannon Stats (have you subscribed yet?).

So what happened?

I’ve seen it posited that Emery offered something new or novel in the build-up structure. I don’t really see it. This is no knock on him.

This look is what so many teams are doing every week — not only against Arsenal, but writ large — and it is designed to bring the pressing distances to a maximum. What was unique about Villa was their high-level commitment to play with confidence back here. Otherwise, it was really just about quality. They have seven mature, composed, skilled passers in back, and there are no obvious triggers. Emery has drilled them well.

Arsenal still fared well in the first half. There were a few high dispossessions, but more often, Villa would be rushed into an unstrategic long-ball. Arsenal would then regroup and form another barrage of possession.

So, what went wrong in the second half?

It was, again, about distances.

At 54’, the ball was regained by Arsenal after a bad Villa shot. Before the cameras even switched back to the action, Arsenal had rushed up the pitch and quickly lost it again. Konsa goes back to regroup.

What is worth looking at there is the Arsenal midfield. Because Ødegaard has dropped deep to form a pivot with Rice, they are far away from where they’d like to be as a pressing side. The distances are just long.

So now, where Villa regroups into their build-up shape, Arsenal have not yet recreated their press. Havertz has an eye on McGinn (who is his usual responsibility) and points out that Tielemans is free. Saka is pinching in to help augment Ødegaard’s responsibilities. Ødegaard and Rice are trying to get back.

And they are unable to get there in time. Both Rice and Ødegaard try to get to Tielemans, but he delivers a quick pass out, and it’s off to the races.

Havertz fought that one back, as he does, but it was indicative of something larger.

We learned afterward that Ødegaard was subbed off because he “felt something,” and this was another reminder of the physical pressure of playing this role, despite its obvious benefits: there is just a lot of space to cover when you are the first to receive in build-up and the first to lead the highest press.

Here’s what we flagged in What Ails Arsenal after the disappointing stretch in December.

It is not without drawbacks, however. For one, having an over-fluid build-up has risks with defensive solidity, as players are often transitioning between zones. With the full-back more likely to be found out wide, the “rest” defending carries a little more risk of being played through. I personally think it’s a worthy risk to take.

But the big drawback is that this shift increases the intensity and burden of two players, at a time when planning and circumstance have left the midfield thin: Ødegaard and Rice. This is in addition to the understandable exhaustion felt by the wingers and the right-back (White).

The above clip shows just how much ground Ødegaard and Rice have to cover. This was exacerbated by Villa looking a bit like Arsenal in back: when Arsenal committed players forward, they’d go long to Zaniolo; when Arsenal hung back, they’d build out the back. Emiliano Martínez would do a simple backline counting exercise. Wherever there were numbers, they pounced.

But the cheap giveaways continued. Here’s another clip from an Arsenal regain. Once again, before the cameras even switch back to Arsenal possession, it’s already been lost, and Villa can start a new attack.

Meanwhile, I never actually got time to post this, but here’s a look at an excerpt from our opposition report on Aston Villa.

When diving through the underlying numbers, I saw how much their performances were impacted by steady middle-third possession, resulting in medium-length passes, especially when it was dictated by Pau Torres and Ezri Konsa. That, unfortunately, is what we kept seeing in the second half — and it was accompanied by some little gaps you never see in the Arsenal block.

Here, Diego Carlos plays it out to Torres. Both teams are in their expected shapes: the compact 4-4-2 for Arsenal, and the swirling 3-2-5 for Villa.

Things speed up here as Saka rushes from the side, cutting Torres’ angle to the wide man. With Jesus up high, Ødegaard is left with dual responsibilities (Tielemans and behind). In truth, the energy just isn’t quite as suffocating as it usually is.

Ødegaard shades towards Tielemans, and this opens up a lane. Most CBs wouldn’t be able to hit this, but Torres definitely can.

And Villa can play through the middle of the settled Arsenal mid-block. I can’t tell you how rare of an occasion this is on the year.

💭 Final thoughts on Villa

All of this compounds. The hasty losses turned into more possession for Aston Villa, which played into the strengths of their back-three defenders (i.e., dictating tempo and possession from the middle third).

When Arsenal have lower possession, they lose two of their key advantages: the counter-press and the set play. These might be the team’s two biggest strengths, period. Aston Villa are pitiful at defending corners in their box, and were able to generate six of their own in the second half — while Arsenal generated two. It is hard to manufacture bailout goals like that.

Here’s what Arteta had to say.

“We were struggling to bring the ball and do what we did in the first half. We lacked a lot of composure, we rushed things with the ball, we never had enough sequences in areas that we wanted like we did in the first half.”

I wasn’t feeling too charitable after the game. I thought that mistakes and losses can happen, but what can’t happen is a team-wide dip in energy across the XI that leads to a dulled threat on one end and consistent possession on the other. Especially when the opponent is awash in injuries, playing on shorter rest, and playing away from home.

Arsenal’s “fully fit squad,” celebrated in these parts, has been a bit of a mirage of late, as there is a difference between “available for selection” and “fit and sharp enough to be trusted to start the most important games of the season.” Partey, Tomiyasu, and Vieira have not yet factored into at the level desired. While Villa had the shorter rest and the thinner squad on paper, they may have been sharper in a broader sense: Arsenal’s starters have accumulated 3,032 minutes on average (or 34 full-90s); Villa’s had racked up 2,527 (or 28).

Meanwhile, here’s what I wrote during the height of the Havertz Wars.

If society loves a scapegoat, the footballing world especially does.

There are understandable reasons for this. These fuzzy, unrestrained passions are why we’re here, and nobody should suggest that players, managers, or executives are immune to critique: they’re millionaires who signed a deed on a house in funkytown. And though most of these critiques are rooted in some truth, we also know that things can get, shall we say, disproportionate.

There is a reliable tidiness to the operations. Last year at Arsenal, it seemed some invisible baton — previously held by Granit Xhaka or Nuno Tavares or whoever comes to mind for you — was cleanly passed from Sambi, to Vieira, to Nketiah, to Holding, and so on. There may be many, but there must always be one.

I’d suggest there is another, more innocent, factor in play: the very human desire for straightforward explanations in a sport that often deprives us of them. Hundreds of millions play worldwide; the best athletes on Earth go through thousands of hours of training, competing and moving and climbing the ranks until the best ones are funneled into a few select squads; they perform in jam-packed stadiums over a hundred or so minutes, having thousands of tiny opportunities to prove their superiority. And yet, entire games, trophies, and careers are regularly decided because of one slip, one bouncing ball, one referee protecting his mate from stress. Everything is hostage to random strokes of bullshit, luck, or variance. Football, as always, is a metaphor for life.

Even when the performance is to blame, the reality is complex. Any number of factors can contribute: a small but cascading tactical issue, a learning curve, a beloved player making a mistake, a phasing-in period, a wet pitch, a genuine recurring problem, an opportunity missed by a blade of grass, a simple bad day, our own expectations.

It can feel bewildering to navigate all that. It’s much easier to yell HEY MAGUIRE, YOU’RE FUCKING SHIT!!!

We are all subject to these forces, and I guess all we can do is try to be aware of it when apportioning blame. Part of the objective of this little writing project is to dive into that complexity with full force and see what we can learn.

Needless to say, Zinchenko found himself the overwhelming target of supporter ire, and I totally understand it. While he provided a great source of tempo against Bayern, not to mention the required passes in the first half of this one, the second half was punctuated by some rough, memorable moments.

Here’s what I’ve said in the past on his work out-of-possession:

I don't want to overstate things, but Zinchenko's defending is more nuanced than black-and-white. He's usually a plus defender around here (the middle third). He still leads the team in dribblers tackled. Not just a volume thing: high success rate (68%) means he's down in sixth in challenges lost.

But continuing:

[It’s a] reminder of how incomplete a picture certain stats offer. Zinchenko has his frailties — the wide 1v1 stuff is what it is, and should be dealt with tactically; I'm grumpier about his high-line integrity — but also: he has his value as a defender, too.

I also said this:

[Longer term]: One reason to work toward Rice as deeper midfielder is psychological. If you’re facing Jorginho #6 + Zina inverting, you may not actually succeed, but you have an idea; you have hope. If it’s Rice, athletic-ish 8, defensive/athletic LB, and you’re pinned — abandon your dreams.

I think that may be the ultimate incarnation of this team.

The high-line stuff was pretty bad for Zina on Sunday. It’s a particular source of soreness for me because it doesn’t only impact his side, but provides space across the pitch to the attackers marked by Gabriel, Saliba, and White. Other than that, when you’re on the pitch for a superpower (deep passing), smaller mistakes may happen, but big glitches are less forgivable, because there aren’t enough ways to compensate otherwise.

Still, without clamoring for a long run of starts or saying let’s not sign another defender or hot-taking, I can’t help but want to keep things in proportion, even though I know it’s so fucking annoying to hear. Of the 50 losses in the second half, Zinchenko had three of them. He went 13-of-14 passing, and it wouldn’t be hard to argue that he needed more of the ball, not less. While he was definitely part of the team’s inability to regain the ball and sustain possession, I can list ~7 players who are more to blame for the actual two goals that were ultimately conceded.

As you’ll see, the defensive duels were more concentrated down the Villa left.

There was a team-wide outage in the second half, and Zinchenko contributed. This isn’t a rosier explanation.

⏩ Looking ahead

In the first half, the team went fishing. In the second, they stood on the shore.

Taking a day or two to write these things can help with perspective. As I watched highlights, I heard a commentator announce the Bailey goal by saying it “was the first time Arsenal have trailed in the Premier League in 2024,” which should offer context in itself. There were a few specific factors in play here, though probably the biggest one is just that Aston Villa are a top-four side in the Premier League, and they played really well.

Arsenal may not be the best squad in the world yet, but they are somewhere in that general discussion. When considering their rivals for that moniker, they have some advantages, but they are also a little less experienced, thinner in end-to-end squad quality, and don’t have quite the overwhelming inertia of superstardom that helps others more readily compensate for their off-days. That should all come in future phases, but it also doesn’t mean glory must be delayed in the meantime.

The Bayern match offers a worthy chance of a reset, and a worthier test of mettle. I believe the gameplan to be fairly clear: mid-block, double-pivot, Havertz up top, Tomiyasu at left-back. That should help with the “clarity” part of the “passion, clarity, energy.” The team generally played really well in the home leg, and also showed some resilience. But that stadium is a boneyard. Nothing is a given.

I’m really looking forward to it. Trossard had a good quote today.

"Just because of one game there is a lot of talk. We have been really good. Especially this year, we were unbeaten until the last game. We just need to keep the right mindset."

If you haven’t read our opposition analysis on Bayern, here it is.

Opposition analysis: Bayern Munich

“We have achieved nothing at all as yet; we have not made up our minds how we stand with the past; we only philosophise, complain of boredom, or drink vodka. It is so plain that, before we can live i…

Happy grilling everybody. ❤️

> This looks like a scene from the spy movies where the hapless henchmen take each other out.

Delightful

The long / channel balls to Zaniolo was a big factor for me. Spotted the usually super-aggressive Benny White holding back on the contests way before he ducked that 50:50 and got hooked. Lost quite a few contests in a row. Maybe Arteta gave him the old don't get sent off message at HT, or perhaps just low on energy levels, because I've not really seen him do that before. Maybe should have hooked him earlier.

It gave them a nice easy outlet, but also something to build from, gain some confidence and quieten the crowd early on in the half.