One left

As a beautiful season reaches its coda, we look at some stories du jour: how Saliba’s portfolio has evolved; why progression has alternated between brilliant and bedraggled; box defending; and more

I’m sure everyone is feeling the full spectrum of human emotions right now. We rooted for Spurs, for God’s sake. What is happening?

This whirlwind will continue for the next few short days.

There are a lot of ways to describe it. At the moment, though, I feel like I’ve reached the final pages of a book I love. For whatever reason, I experience this differently than when the credits roll on a good movie (what the educated call a “film”). Books are more of a time investment. Bad books suck particularly hard; they turn into frustration, even resentment, toward the author. But a particularly great book is intimate and personal. As the pages dwindle, I read slowly-slowly-sloooowly, desperate for the story not to end.

That’s where I am right now.

I have heard there are other books in this series. I apparently have many others to look forward to.

But I love this one.

¡Saliba!

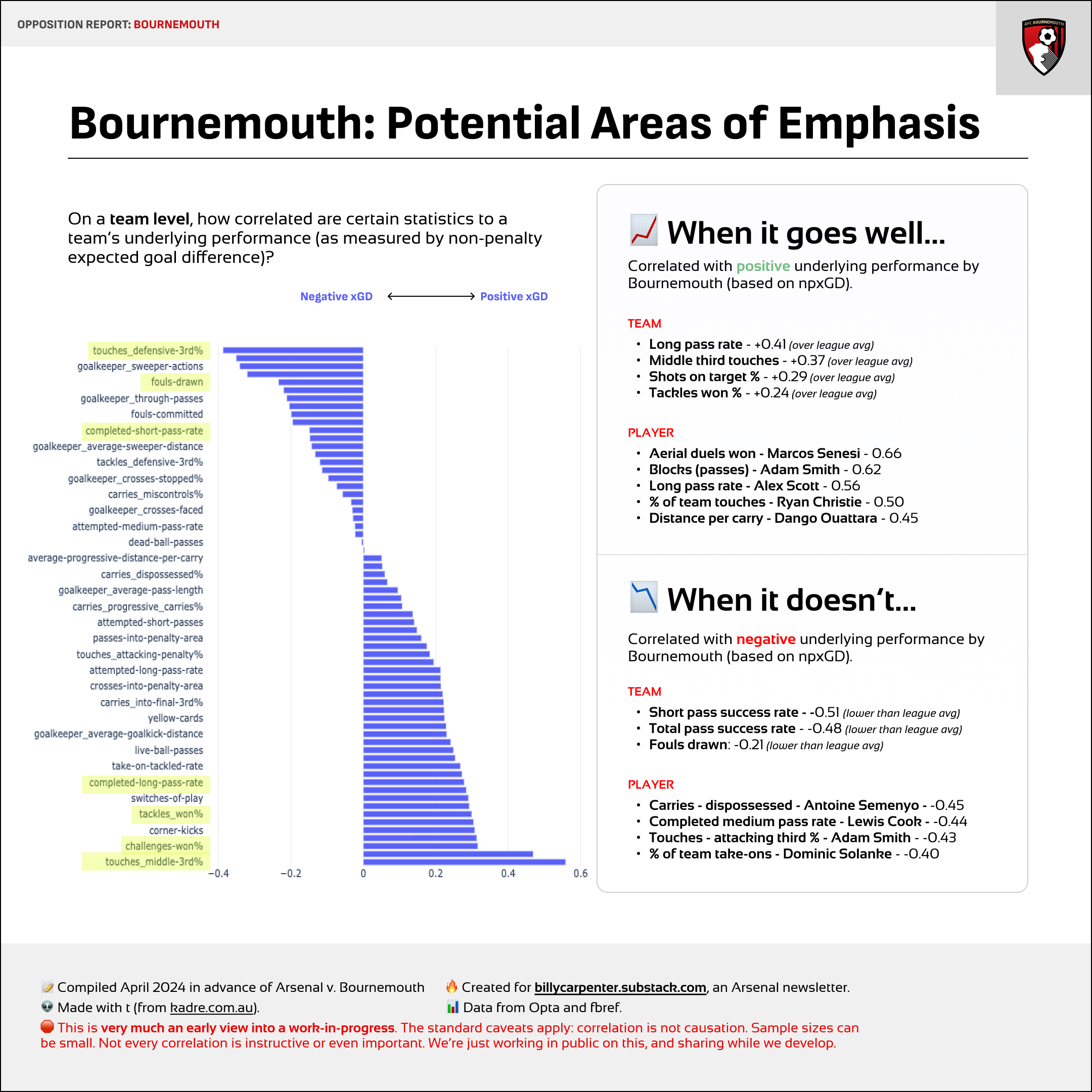

It feels many moons ago, but Bournemouth presented a tough challenge. They’ve been the fifth-best team or so since mid-November, when they went on a seven-game undefeated streak and never looked back. Here was our opposition report.

Andoni Iraola has been managing his tail off — never feel too confident against a Basque with a tactics board — and once the full detail of his press settled into the team, they have become a truly bothersome opponent.

Arteta was effusive in his praise of his own team’s performance after that one. He knew it wasn’t going to be easy.

“I never expected it to be. We started the game with probably the best first half we’ve played all season. I think we were unbelievable, we were super composed on the ball, really aggressive without the ball, we generated so many chances, we could have scored three, four or five easily.”

There were many candidates for Arsenal’s player of the match in that one, but I found myself the most gobsmacked with one William Saliba. As you saw above, that opponent has a potent attack; they are especially thoughtful about getting their attackers in good positions on long-balls and then attacking 1v1. Saliba was up to the challenge, showing the “unbothered” vibe of a Van Dijk, calmly deleting everything.

There were a lot of these.

And in the moment that was probably most noticeable, he carried up, cut through the half-space, and ripped a cutback shot on his left-foot. Somebody replied that they love it when Saliba “lets his intrinsic thoughts win.”

That carry is more than a fun moment. It’s a symbol of how some of his responsibilities have evolved during the year.

In the preseason, James McNicholas had a wonderful article about how Saliba would be given even more responsibility in build-up during the campaign ahead.

With the French centre-back restored to fitness, Arteta spent the weeks before his team’s opening Premier League game against Nottingham Forest meticulously recalibrating their build-up play to give him greater prominence.

The goal was to get Saliba on the ball more frequently and in more central areas. It has proved a subtler difference, but a difference nonetheless.

Last season, build-up responsibility was shared almost evenly between Saliba and his central defensive partner Gabriel Magalhaes — Saliba averaged 69 passes per game, Gabriel 63. That slight disparity has widened since the start of the new one.

This vision began with a fascinating flourish, as Arsenal debuted an interesting 3-4-3 look in the opener, with Timber at “LB” (left CB) and Gabriel on the bench. This is the “three diamond three” that may have been the planned low-block killer.

Saliba held a ridiculous amount of responsibility, going 121/123 passing on the day.

You could really get a sense of how central he was through his “received passes” map. He was the spine.

This has promise for several reasons. For one, Saliba is perhaps the preeminent “CCB” (centre-centre-back) in the world; if not, he’s in the running. For another, in a season bent on “dominance” and/or “control,” he is measured in possession, and unlikely to post many dangerous losses. And finally, the likes of White and Timber (and Tomiyasu, Kiwior, and Gabriel) are great at these “outside CB” roles where they push up to join the attack.

A few things have changed. The primary one was the simplest. Arsenal lost the personnel to do this in the way envisioned. Partey has been out for most of the year, Timber busted his knee, and others have been in and out.

The other thing that happened was that Gabriel took another big step up. He’s made himself indispensable to the XI, if there was ever even a question. While there may have been other factors in play back then (the transfer gossip mill was a-swirling, as it always is), Gabriel has since been one of the team’s most immense performers throughout the season. It’s hard to picture Arsenal playing without him.

And so they returned to their roles, often with Raya splitting them and funneling play out from there.

The difference from last year was that Saliba was more touch-dominant as play increasingly pushed right. This kept things safe and secure, and with Rice at the #6 role, Arsenal dominated possession, field-tilt, and any metric like that.

The issue, though, as teams continued sitting back, was a lack of vibrancy in the final third. Final actions are not just final actions — they are the product of earlier machinations — and Arsenal began to struggle in creating a sufficient amount of open-play chances, as we covered in-depth in What Ails Arsenal.

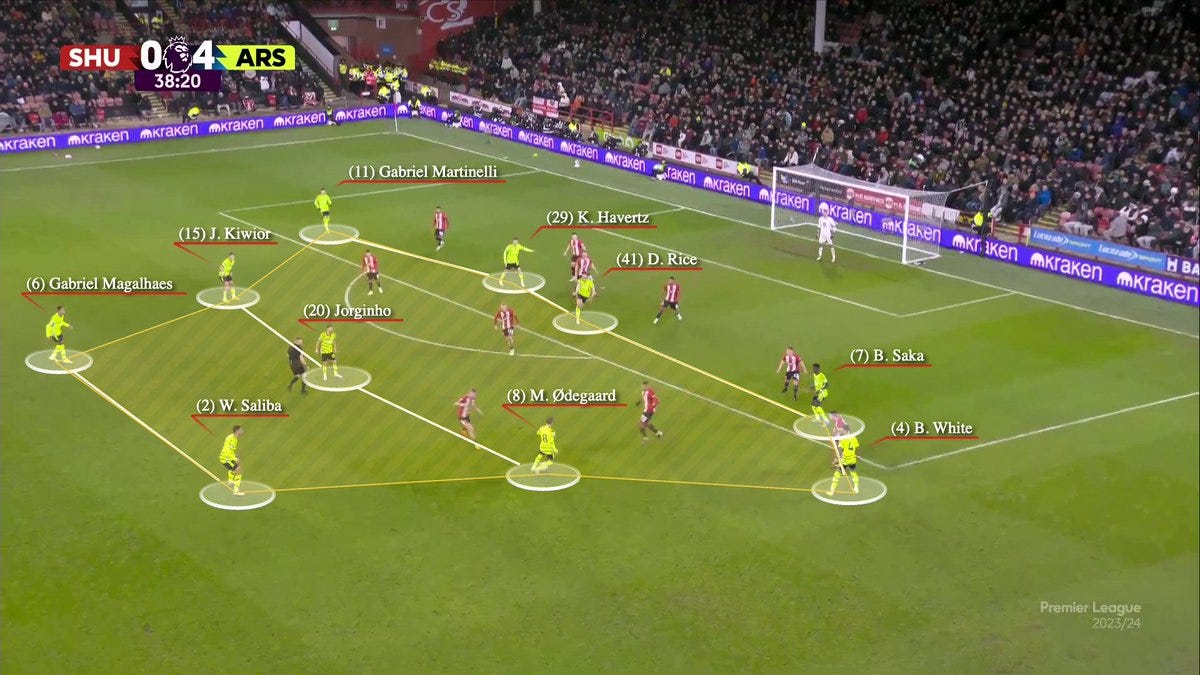

Multiple fixes were pushed to production, which we’ve talked about ad nauseam: Ødegaard dropping, Jorginho playing more, Havertz playing in the #9, and the team getting healthier. By and large, the squad has moved to a double-pivot system where the midfielders act like midfielders, the full-backs act like full-backs, and the striker drops a bit but is still a box presence. Sometimes, the best solutions are the most straightforward. We’ll cover that more in the next section.

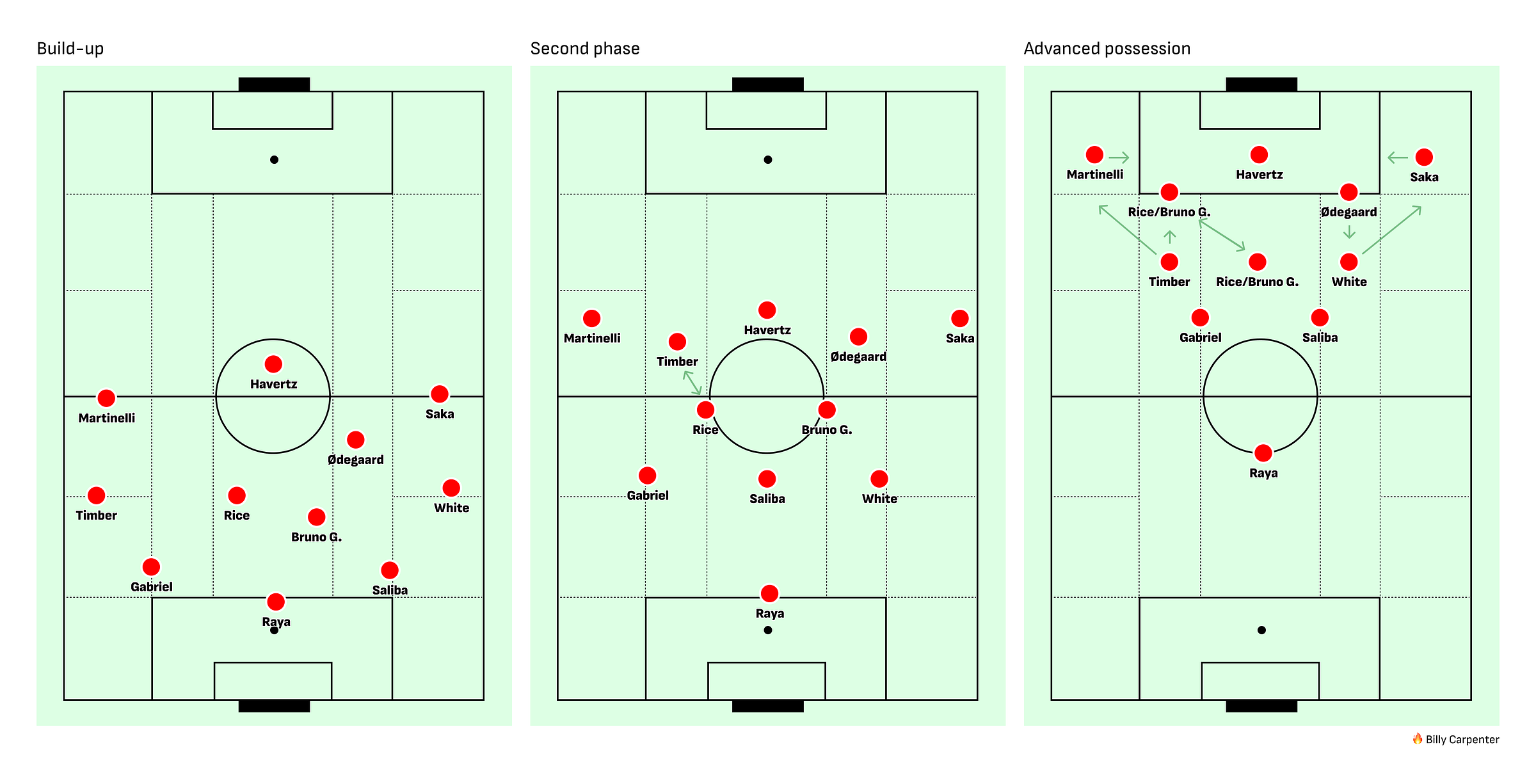

But what we’ve examined before, and will continue to examine, is the continued evolution of the usage of our centre-backs. Here is a diagram of the team in advanced possession, with a standard 2-3-5 look that we often see. That’s normal:

This, of course, is how we achieved this museum piece.

The diagram below is also normal. Gabriel often joins the left in advanced possession. Because of the security of Saliba in back, the team is able (at least in theory) to push up on the left to create overloads.

But the final image (below) is what we are seeing with a bit of increasing frequency, depending on the opponent: Saliba pushing up to join on the right.

There are a couple of reasons behind this. For one, the double-pivot midfield helps with security in the event of a ball loss. For another, Gabriel has (generally) been more measured and less error-prone this season, reaching another level. Saliba isn’t just a pure destroying CB, as I don’t have to tell you; he’s extremely agile in these spots, and showed a lot of strength as a carrier in France.

So, for instance, you can see Gabriel get the ball in the middle of the pitch here, then dish it to Saliba before regrouping back to CCB. This now allows Saliba to stay up and try to push the envelope further on the right.

When play recycles and the team regroups, either full-back can join the back-three build-up shape that Arsenal employ in the middle-third, and either CB has been playing centrally. This increases the modularity of it all, and you can easily see how Timber (or Hato) could fit into this. (Not to mention Kiwior, who did that very thing.)

Here, you can see Gabriel joining his left side — then, how quickly things swing to allow Saliba to push up on the right and keep “good height.” Gabriel drops back.

This all continued against Manchester United, where Saliba didn’t just win my Man of the Match, he won the official one, too. He was every kind of CB: the calm sweeper, the touch-dominant orchestrator (who was often let down by the next touches 😬), the progressive carrier, the aggressive wide defender.

In a day when there were a few dangerous (and sometimes uncharacteristic) losses by the squad writ large, he calmly swept things up.

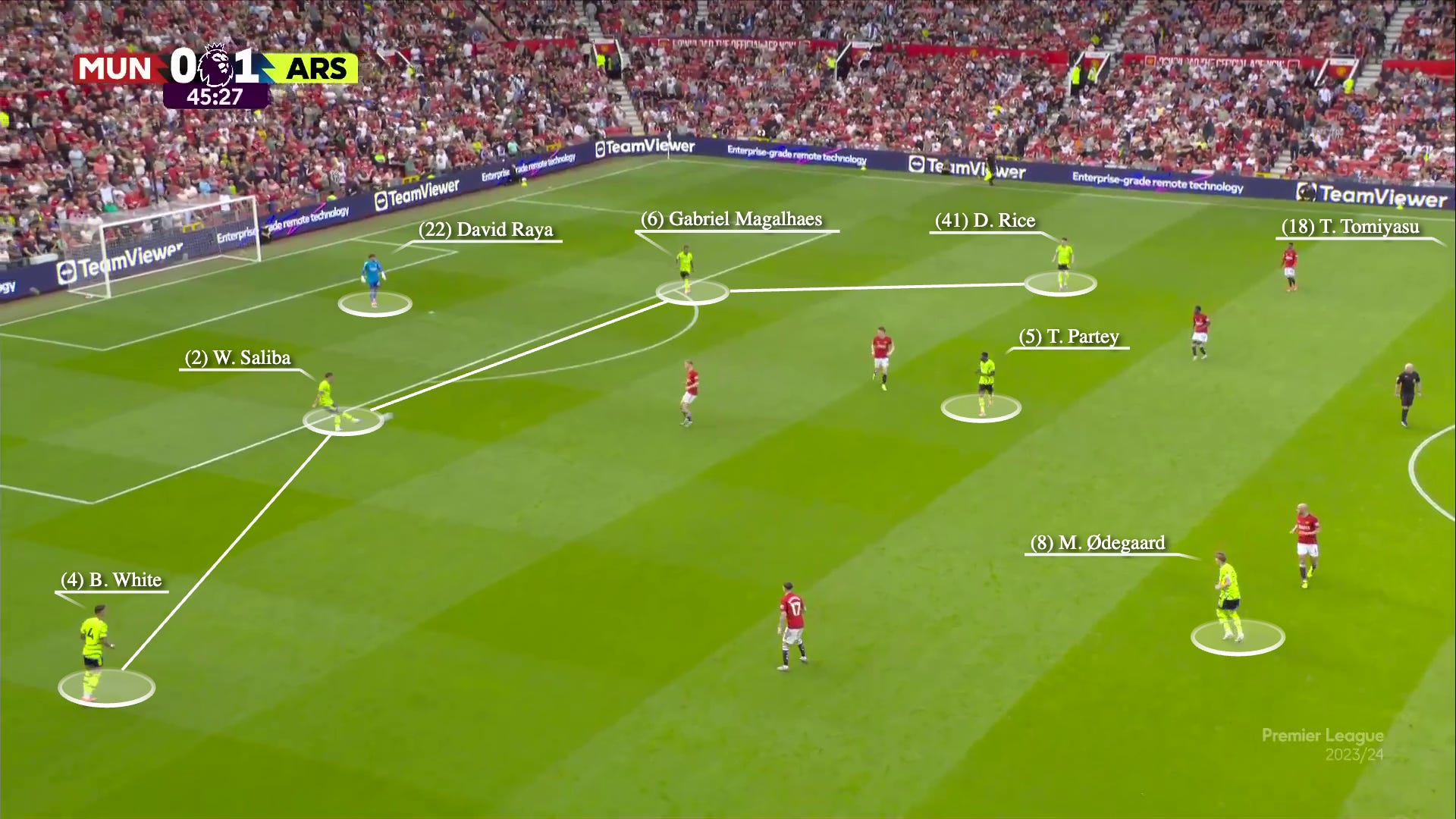

In the below moment, you’ll see how playing with four CBs — and trusting both Gabriel and Saliba to be “CCB” — enables the team to seesaw both in-possession and out-of-possession. White is pushing up to man-mark, so Tomiyasu swings back on the other side, which means the “back-three” is Saliba, Gabriel, Tomiyasu — with Gabriel in the middle.

When White gets beat behind, it’s up to Saliba to stop the opportunity. I don’t need to tell you that this is ridiculous. He’s side-on. He’s patient. He waits for the right touch to jump in. He’s conscious of angles. It’s just so hard to attack this.

Saliba also felt the security behind to carry forward as he saw fit. Arteta generally dissuades his CBs from trying dribbles to get out of situations. At the same time, it’s a Saliba Sword that shouldn’t be fully sheathed. Gabriel is shading over to cover a bit in the event of a loss:

Twenty seconds later, Saliba gets it as the RCB and carries it forward again to try and discombobulate the Man United shape. Relentless.

When we investigate tactical permutations, we can often look up the pitch. How are the midfielders working together? What are the dynamics of the attackers? Are the full-backs inverting or overlapping?

Especially when a CB duo is as stable as the Gabriel-Saliba partnership, we can miss some of the smaller updates that impact their roles on a week-to-week basis. For Saliba, here’s a quick look at how it has played out at different stages in the season.

This is not to say that Saliba does an entirely new thing now. But it does mean more options are at the team’s disposal. This has manifested in some interesting ways, statistically. For instance:

Last year, Saliba had 5+ touches in the attacking third on two occasions. Both times, it was when Arsenal were chasing games late. He has now done that fourteen times this season across comps.

Since Dubai, his touches have been more evenly split with Gabriel, and he has been a little more free to move forward. Of note:

Pre-Dubai: Saliba had 86 touches per 90, Gabriel had 71

Post-Dubai: Saliba has 75 touches per 90, Gabriel has 73

Gabriel’s lower-third touches have raised a bit while Saliba’s have gone down; despite 11 fewer touches per 90 overall, Saliba’s advanced input is a bit higher

Saliba has doubled his attempted direct take-ons after the break, though we’re talking about low numbers (0.25 per 90 to 0.53 per 90)

The result is a pairing that is a little more balanced. As Gabriel splits some responsibilities, and the midfield is more likely to contain a double-pivot of confident passers, Saliba has been a little bit more low-touch. Gabriel has shown increased solidity at CCB, but if you’ve seen a couple more mistakes in the second half of the season (compared to his imperious, “I have no notes” first half), it’s probably not unrelated to the fact that his responsibilities have risen. So too has Saliba’s forward threat.

Saliba is not one thing. He is the uber-calm orchestrator and sweeper that we saw last year and for much of this one; in fact, we saw it again in a 177-touch game against Sheffield United, and the 98-touch performance against Manchester United. But he can also push and unsettle things up high, while acting like a wide-CB as needed; he showed this against Bournemouth, when his touches were lower (58) but his advanced involvement was higher (5 touches), all while destroying the Bournemouth attacking nexus.

Instead of limiting him to one set of responsibilities, it can be tailor-made to what is most damaging to the opposition. What a treat.

What’s happening in build-up

The past few weeks have seen many updates to Arsenal’s build-up. This is best typified by the additions of Thomas Partey and Takehiro Tomiyasu to the XI, which have had major impacts throughout.

Structurally, the team has generally looked at its most swirling and rotational. Do you remember how wild shit got at The Kenny?

Yeah, it’s been a bit like that at times.

Against Chelsea, Partey was over-direct for a half, which got contagious and led to a basketball game; once the team settled down and got into the right rhythm, the Blues’ midfield had sensory overload and things were devastatingly effective.

Tomiyasu is, well, just going wherever he pleases.

Facing Bournemouth, things were generally impressive from a structural point of view. With this lineup, Arsenal boasts nine outfield players who can comfortably join a midfield pivot, and I really like the feel of this 3-3 shape once Raya is out of the mix.

Most of all, the double-pivot of Rice and Partey (with Tomiyasu joining in) offers a really nice stage for Ødegaard to shine. There is a difference between Ødegaard floating to fix problems (i.e., progression won’t happen without him) and Ødegaard floating around to create problems (i.e., finding little overloads and weaknesses). The latter feels like the best use of his abilities.

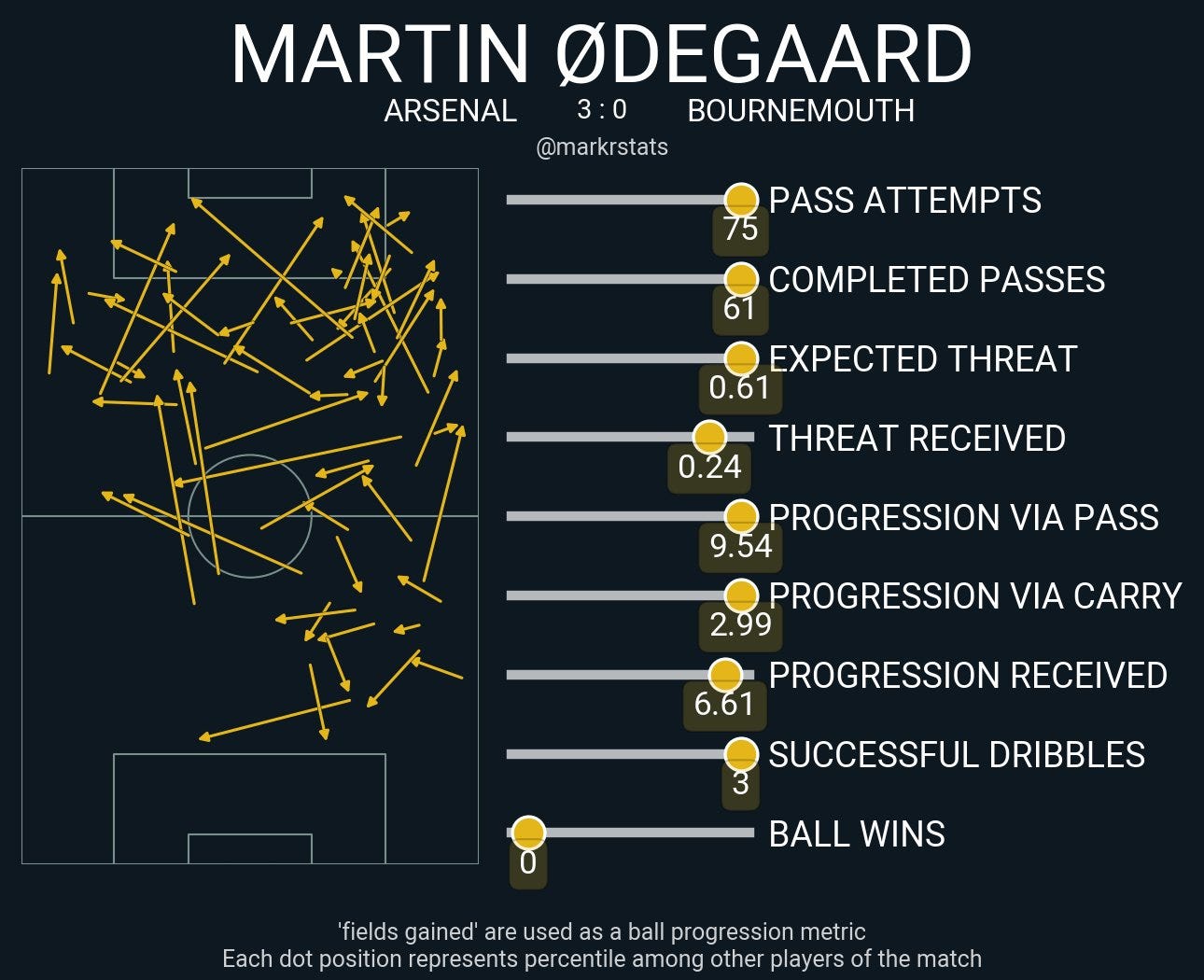

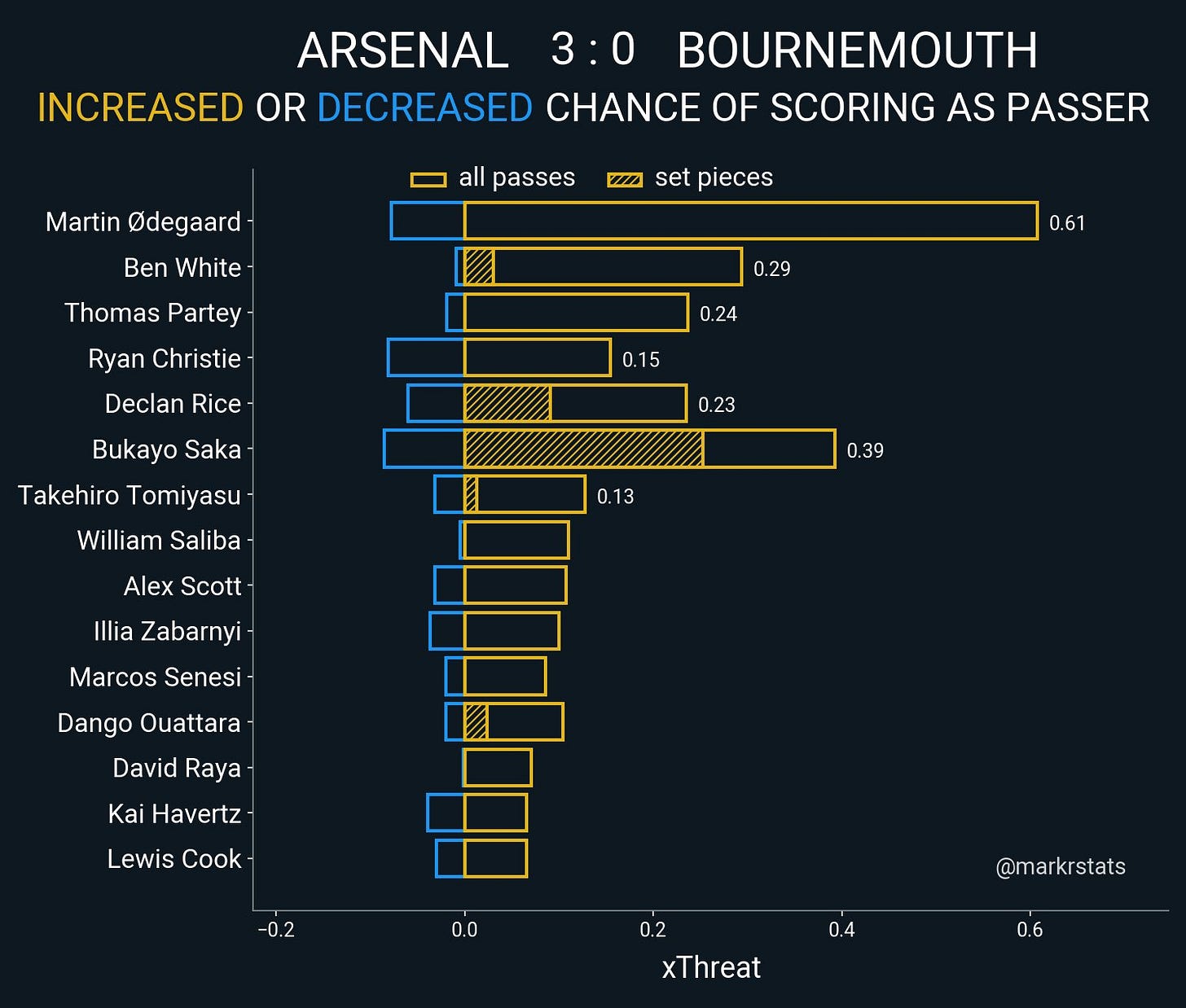

The Bournemouth game felt like a near-perfect portfolio of responsibilities for him. When he wanted another player to push up, he’d drop and join the pivot. When he saw a weakness on the left, he joined that side and hit some great balls. When there was interplay to be done on the right, that happened too. There were no artificial constraints.

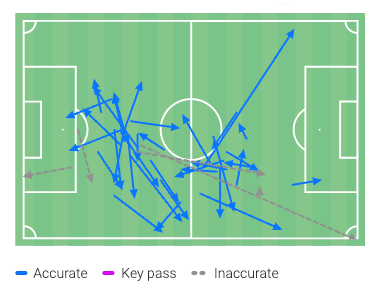

It led to an overwhelmingly successful passing day.

In that one, he managed twenty-two line-breaking passes.

And his floating was reciprocated by Havertz. It seems clear that Ødegaard is well-served by a galloping striker making aggressive runs. Here are those passes.

It even showed up in the type of pass that I seemingly call for every single week: the back-post cross from the right half-space. Ødegaard’s crosses have been too far and few between to my liking, and this is one of my absolute choice methods of chance creation: the line gets sucked down; the keeper has to mark the near-post and the whole goal; a pocket almost always appears. Rice narrowly missed.

In all, this gives Ødegaard the freedom to move around — which also gives Saka more access to the right half-space. This little triangle has been one of the more productive units in world football.

Art de Roché had a typically great article about the league’s most creative partnership.

In the Premier League, Odegaard ranks first for chances created from open play (81), shot-creating actions (205), through balls (39) and passes into the penalty area (120), and second for total chances created (94), progressive passes (324) and expected assists (10.5). Saka ranks first for expected assists (10.7), third for chances created from open play (68), shot-creating actions (183) and passes into the penalty area (70), and fourth for total chances created (88).

This comes through when perusing the stats.

Ødegaard leads Europe in passes to the penalty area (123) / Saka leads Europe in *touches* in the penalty area (271)

Ødegaard is third in Europe in progressive passes, despite attempting 1595 fewer passes than #2 (Rodri) and 1325 fewer passes than #1 (Xhaka) / Saka leads Europe in progressive passes received; he has 132 more than the next highest player

They are #3 and #4 in shot-creating actions in all of Europe

Saka has 34 fackin’ G+A across comps despite being double-marked every second of his life

We had a nice little Saka propaganda section in the last edition. He’s our most important and influential player, to these eyes. Because of his skill, completeness, and the attention he is paid, I find him almost incapable of having a bad game; if his shot isn’t finding the net, he’s still dragging two defenders away from everybody else, winning the ball back, getting fouled, creating, delivering on set pieces, and more.

As I’ve written elsewhere, firmly in my Bias Era: “The objective of every Arsenal gameplan is to move heaven and earth to manufacture 30 seconds per game where Bukayo Saka is defended like Phil Foden.” He is my Arsenal Player of the Season, for what it’s worth.

Below, I pulled all of the team’s goal contributions, and highlighted those by Saka and Ødegaard. It offers a clear picture of how ever-present this duo has been.

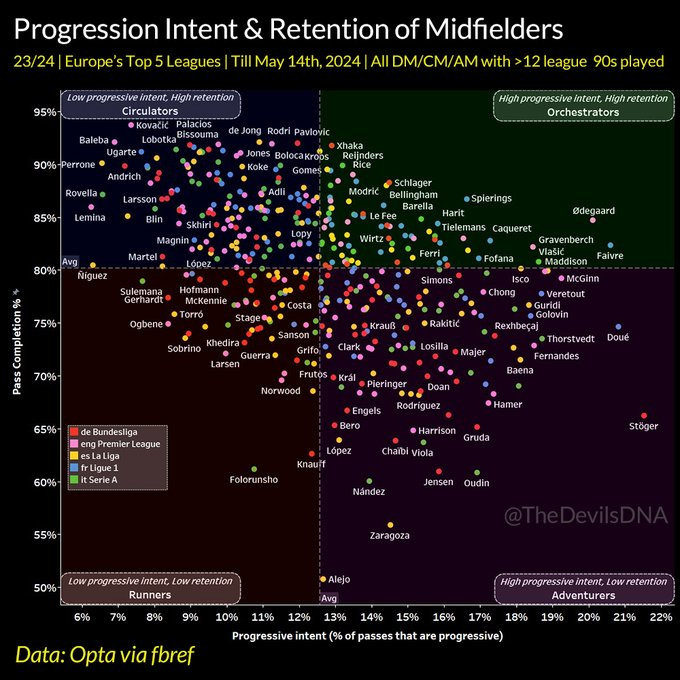

In the following graph from my friend The Devil’s DNA, you’ll see that Ødegaard may be the single player in Europe you may choose when considering the balance of security and possession.

What may be most promising is that Ødegaard didn’t have the opportunity to show what he could do all year. Until early-December, his role was more constrained, and he was reportedly nursing an injury.

Even with that factored in, he leads Europe’s Top-5 in passes that break the last line.

Floating atop a clearer double-pivot — one that is able to balance tempo and directness in more nuanced ways — the possibilities look exciting. While I’m trying to live in the glorious now, I’m human, and drew up what it could all look like with a player like Bruno Guimarães.

With Ødegaard getting some of his lower responsibilities covered, he’s able to move lefter-and-lower naturally, and Saka is able to access the half-space with a lot more frequency.

We’ve seen plenty of examples of the benefits of fluidity. On Sunday, we also saw some of the downside.

Why progression largely failed against Man United

Since the lineup with Partey and Tomiyasu was unveiled, we saw two 3.3 xG performances against Chelsea and Bournemouth, which is good for the joint-fifth-highest tally of the year. But in those four games, Arsenal have also had all three of their lowest-possession games of the league season against opponents not named Man City or Liverpool. Bournemouth was the only game where Arsenal had more of the ball.

The game at Old Trafford was in line with this trend. One commentator likened it to a Phony War in which Arsenal were happy to get out of Old Trafford with a win, and Manchester United were happy to not be embarrassed.

It started dominant then sloppy. Partey lost the ball by attempting to let it run, and Højlund slipped while getting a dangerous shot away. Things got cagier from there, and Partey became more ancillary and conservative with the ball. The team didn’t have a tempo dictator out side of Saliba.

Still, I saw plenty of structure that I liked. As I’ve said, I really like this “3-3” look that offers plenty of support low, wide, and high. It’s hard to defend and the distances are good.

Here, still in the first half, we saw Tomiyasu joining the pivot and Rice swinging wide. This forms a 4-box-2 that we saw against Liverpool. While Tomiyasu is a bit of a decoy in the middle, Rice is nice and dangerous when he swings to the wide position.

So a lot of the issues were simple and human. The brilliance of Havertz in delivering the goal helped mask some of his struggles in hold-up; I had simply forgotten that he had some rough giveaways like this in the middle third.

Here’s another one. The structure looks just fine to me. Havertz could have played this one-touch to Ødegaard (difficulty level: fairly high) or just hit it back to Saliba-to-White to get around the Man United press.

Going into the second half, I was interested to see if any changes would be made to reinforce the build-up and increase possession. I didn’t love what I saw right away. Rice drops to form a sort of auxiliary LB, and then Partey is alone in the midfield. Raya’s abilities as a fake-CB are not exploited here, and the distances just don’t feel right.

When the play funnels right, the lack of options bites. Everything is pretty easily closed off and White just has to hoof it.

I’d split the CBs wider and make sure the double-pivot is always a double-pivot; Rice can stay within the block or, if not, Ødegaard should drop.

…and, how convenient, that’s what we saw more of next.

This is the en vogue deep build-up shape of the day. It’s popular in Brighton but seen all over the place: a GK dictating play, wide CBs, a tight double-pivot, and players far up the pitch from there. You have the option to go short or long.

But it didn’t really pay off. Again, most of it just came to regular human imperfections on the day. I do think that Tomiyasu is a little unpredictable for both friend and foe; he’s missed a lot of time, played in multiple positions, and immediately goes back to doing all kinds of wild, expansive stuff all over the pitch. As fun as it is, I don’t get the sense that his teammates know exactly when and how he’d like to receive it.

There were other simple missed passes like this (Ødegaard had a couple, too). Saka apparently passed a late fitness test to play.

These little imperfections combined to ensure that Arsenal couldn’t consistently string together enough passes to dominate possession. It increasingly became hoofball.

This is a tricky balance to strike. Arsenal are at their most pleasing to watch when they are rotating like mad, “total footballing” it across the pitch. But this showed some of the dangers of this fluidity, and sometimes, there is nothing better than a couple of midfielders playing close together and picking apart the opponent shape.

Instead of fighting these issues too hard, Arsenal settled down in their block and dared Man United to make an impression.

The gameplan at Old Trafford

Here was our opposition report that we published before the game.

Interestingly, the #1 negative correlation highlighted there was André Onana getting touches. This may seem quizzical because he’s brilliant with his feet, but it has a lot to do with how Manchester United set up for him in possession, and also the type of players he gets to pass to in build-up. The more deep touches they have, the worse they do.

In fact, Arsenal scored directly off an Onana touch. This has been covered in-depth by now, but Casemiro was slow to rejoin his teammates, which left an acre of space onside for Havertz. As Havertz was headed back, he clocked where Casemiro was. That’s what we call effective scanning, my beauties.

From there, he raised his hand and White hit him with a ball over the top.

…and Trossard delivered another clutch one.

Out-of-possession, you can see the focus areas as well. Manchester United can be benign when they aren’t in transition, so by laying back, you dull their primary means of chance creation. Still, the United midfield seemed a little more balanced and functional than usual, and there was a nice dribbling threat from the wings.

The Arsenal 4-4-2 block usually looks incredibly linear. The players are mindful of their distances and move together as a unit. Virtually no team has actually broken it down this year; Villa perhaps came closest in that second half.

Against Manchester United, however, things looked a little different. I’ve been plenty cranky with Partey over the past few weeks for his tendency to drop back instead of backing up the press; this has been exceedingly rare this season, and leads to more open space in the middle of the pitch for opponents to dribble through.

In this one, it was so extreme and consistent that I think it was instructed. For most of the game, it almost looked like the “Stones Role” as much as a defensive midfielder — he found himself in the backline more than not. He often filled this space, which would help Manchester United keep possession, but would also clog up the box and make it hard to actually generate a threat. It reminds me of the kind of shift put in by somebody like Edson Álvarez.

This game wound up being a prime example of what PSV coach Peter Bosz identified as a special characteristic of the team.

“Me and my coaches studied them. What is it that they do differently to us? The answer is they are outstanding in the opposition box but also their own. They get a lot of players behind the ball as soon as possible. They do it with 10 or 11 but we only did it with six or seven and then the distances are bigger. It’s the transition.

“We showed the players and, in the games after, we started doing it with 10 or 11 like Arsenal, staying compact in attack and defence.”

Here, the team was pressuring ball-side in a bit of a messy moment. Dalot did a great job of picking a pass directly to Højlund. He seemingly has space and time.

But here is what it looked like by his second touch. Under three seconds.

That, ultimately, is what has raised the floor so much for Arsenal this season. They were nowhere near their best, and there are plenty of exciting chances for improvement in the future. But when you see a left-winger like Trossard in that picture, defending the penalty spot with his life, you see how Arsenal have the defensive record they do.

As tricky as it felt, the opponent was only able to muster 0.5 xG with all that possession. David Raya has averaged 1.4 saves per match since Dubai. He had to make all of two on Sunday.

It’s been a joy to watch this team this season. Next steps are not guaranteed, but the future is awfully bright. I’ve been so grateful to be on this journey with you.

In the present, we’re coming up on the last page of this volume. Anything can happen.

❤️

Have loved your articles this season, Billy. Helped me so much to get through an arduous title charge where it seemed everyone wants us to lose to City.

As you said, one more, then it’s back to Arsenal fans’ day job; yelling at each other about transfers.

If you don’t enjoy the journey in football, your life will mostly be miserable.