Block buster

An exploration of the build-up structure used to hammer West Ham, what the risks and trade-offs are, how it contributed to more vibrant attacking play, and what it all means for the rest of the season

After the win against Liverpool, Arsenal had reason to feel confident in their general approach against top sides, hard as those games will continue to be.

West Ham was to be a different beast.

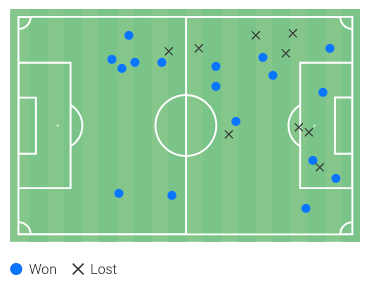

After a supremely frustrating loss the last time out, the team has continued to refine its strategies against lower defensive looks. The Hammers, meanwhile, hadn’t won since the last meeting. Arsenal sought revenge, and this shot chart had to be exorcised.

Many of the underpinnings of the Arsenal strategy were there in the last two months. With some fascinating tweaks — White in here, Kiwior out there, a flood of players joining the build-up — I was most curious to explore the “why” behind what we saw, and examine how it all may impact the closing months of the season.

West Ham will not be the last side who attempt to patiently stifle the Arsenal attack and then spring on the counter. Given the success of this particular operation, there is much to learn.

Let’s get into it.

🤨 What informed the approach

Against Liverpool, what we saw was a very clear, disciplined build-up structure against a top side. There wasn’t much fairy-dust complexity to it: the goalkeeper acted like a goalkeeper, the double-pivot midfield acted like a double-pivot midfield, the full-backs (generally) acted like full-backs, and the wingers acted like wingers.

The real point of intrigue was that Ødegaard and Havertz dropped into corresponding zones to form a box midfield. This was a way of overburdening the still-ambitious Liverpool press.

There are many benefits to a highly structured build-up. If your objective was simply to progress it across the half-line, then this is the right option. Because you have natural advantages — the ball (which moves faster than the man), skilled passers (one hopes), a huge pitch, a keeper as a plus-one, and the ability to drop players down to achieve easy overloads — a strictly positional build-up seems like an easy choice.

There are two other advantages to that steady build-up structure against a team like Liverpool. If you’re able to transition from build-up to attack immediately, you can catch their high-line in transition, and exploit it like this.

You can also pull the press down, commit 6-7 of their players forward, and then exploit that aggressiveness over the top.

That all took place against Liverpool. But these advantages aren’t as readily available against a team like West Ham in a neutral (or negative) game state.

So here’s what we said before this one.

West Ham, looming tomorrow, is a different beast — a beast who cares not for your “underlying performance,” looking to frustrate your attack and then punish mistakes mercilessly. It will require a different set of tools.

Different tools were required. The reasons are this:

An entrenched, deep 4-2 build-up like this can be overkill against a team that isn’t committing a lot of players forward in the press

A team facing a lower block needs dynamic arrivals into the frontline, and a player like Jorginho doesn’t provide that

The most practical factor was that Jorginho and Zinchenko were set to miss this game, and the team has struggled to generate threatening progression without them. It’s usually a one-or-the-other type of deal. Arteta had to work this problem, lest things look a bit like Fulham again (which in many ways, was a one-off, but one to keep in the memory bank nonetheless).

You may also remember how the team had some trouble finding a cutting edge in the early months. If progression is disciplined — though expected — you will usually have defensive solidity, especially with Rice in the middle. But if the opponent is just sitting back, an academic build-up will become an academic push forward, and the ball will arrive into the advanced areas in the expected ways.

With Nketiah parked in the middle and Ødegaard parked in the right half-space, for example, there isn’t a lot of opportunity for the other three (usually Saka, Havertz, and Martinelli) to arrive or rotate in interesting ways. Any rotations from there feel a little forced and artificial. You wind up with a lot of situations like this.

Which brings us to Sunday.

The central point of this article is this: a more dynamic build-up leads to a more dynamic front-line attack. But there are trade-offs, some of which were dulled or avoided in this one. They are nonetheless there.

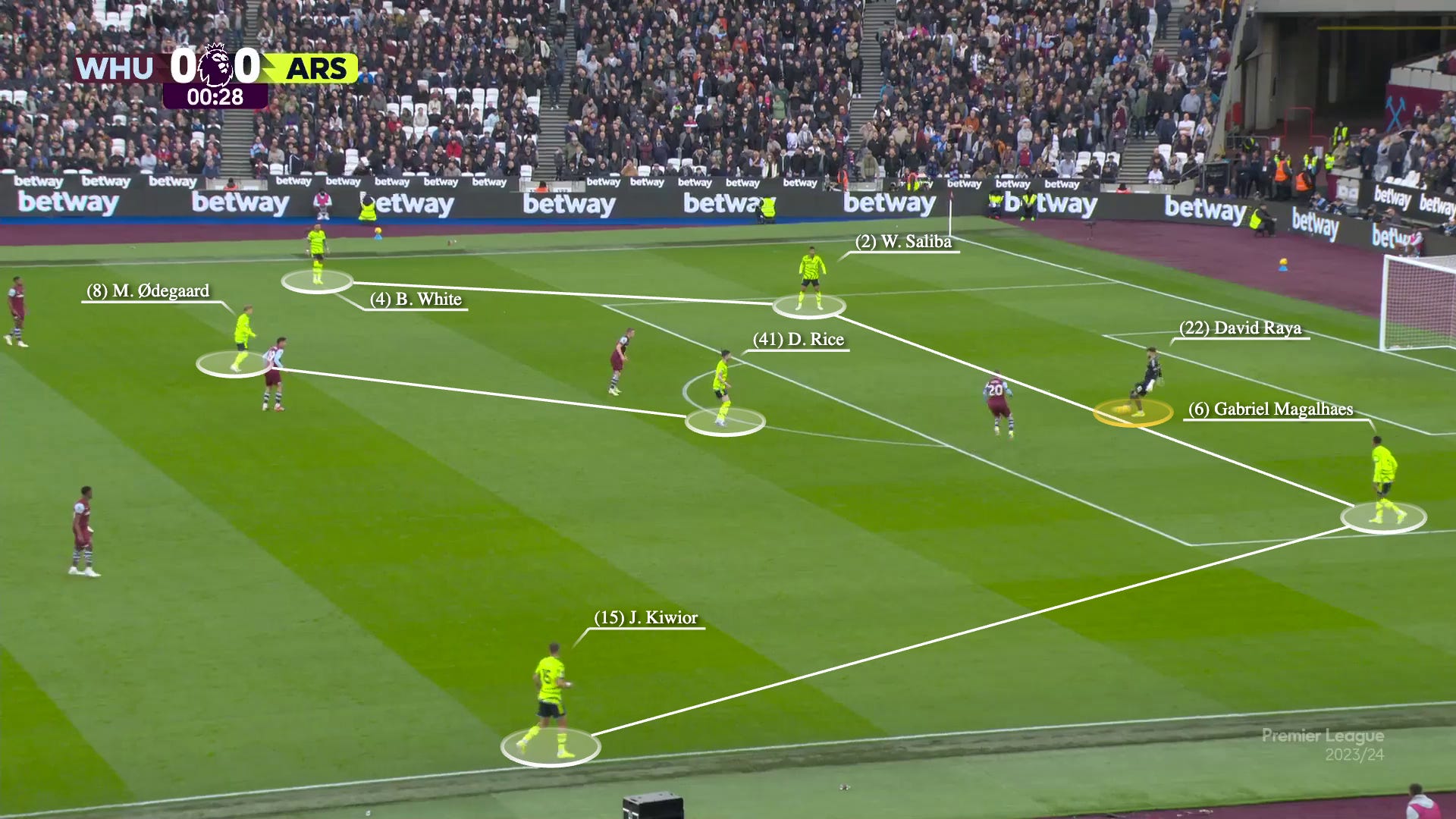

Within the first minute, we saw the below.

West Ham was (somewhat surprisingly, at least to me) committing players forward in the press. The numbers of a press don’t matter so much as the intent, but for ease of understanding, there were four defenders deep with one DM (Souček) sticking close to them; then, there were two narrow wingers with another DM (Álvarez) through the middle; then, Ward-Prowse and Bowen up top.

Based on those numbers, Arsenal sought to generate a 4-2 that could draw West Ham down and outnumber that press by two players (including the keeper). So in response, we saw a wide 4-2 look, but with Ødegaard (instead of Jorginho) joining the pivot.

🇳🇴 Ødegaard and the pivot

Outside of the new signings, Ødegaard’s more expansive role is the central thing to know about Arsenal’s season so far. This started in early-December, and the impacts have been enormous; there is a discernible before-and-after quality. Any good analysis must make it central to the story that is presented.

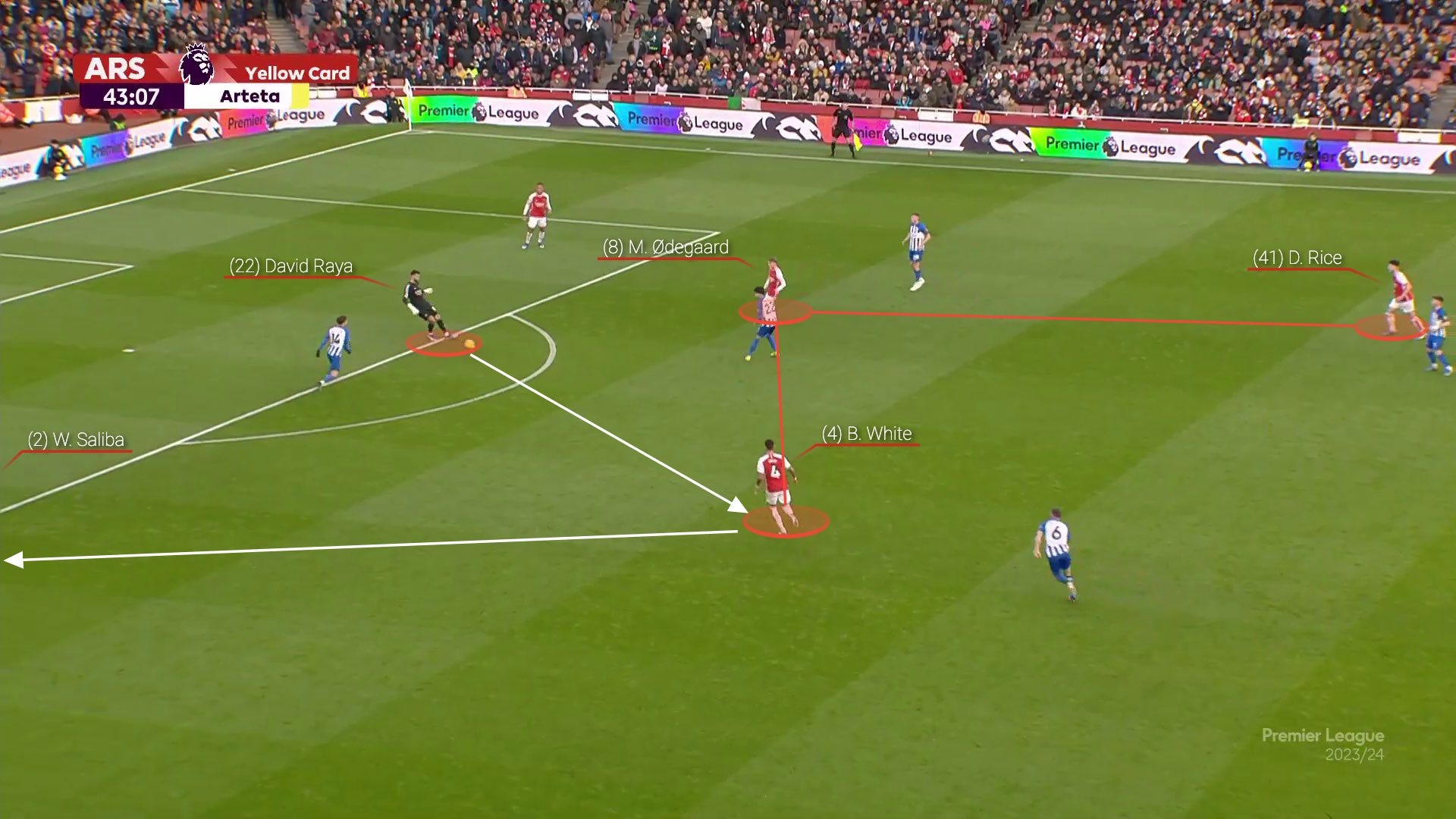

By comparing two games against comparative pressing structures, we can see how his mandate has shifted.

Since he got the keys to the castle against Wolves in December, Ødegaard has had the four highest-passing games of his club career — going back to his teenage days. West Ham was a new career-high for passing attempts, with 112.

Whereas he floats around on top of the double-pivot in a game like Liverpool, he becomes the pivot in a game like West Ham, settling alongside Rice. He usually shares some of that responsibility with another player to varying degrees. It’s often Zinchenko.

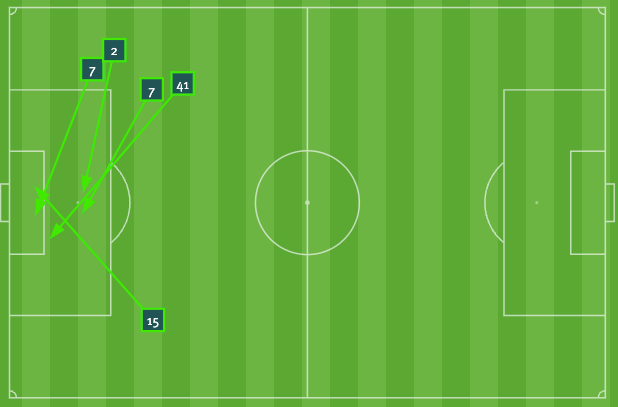

At West Ham, here was his passing map.

For a side that previously had issues with cutting progression, he had 40 forward passes. To give you a sense of proportion: against Chelsea and Tottenham earlier this year, he was shadow-marked out of play, and asked to create space for others (which wasn’t properly exploited). He had six forward passes in each of those.

Meanwhile, Declan Rice had two assists and a screamer, and has been giving those “angle bias” claims a nice long nap.

As this game progressed, there was less need for that sixth player in the build-up, so we started to see some evolutions. It largely turned into a situation where either White or Ødegaard would be low, but not necessarily both.

Here, Ødegaard dropped to help in build-up, so White floated up to the right-hand side to hold width as a winger. Remember what we were saying about wanting to get Saka his touches in this half-space? Here’s how you do that.

And that’s when we started to see a polar bear in Arlington, Texas.

🐻❄️ White in midfield

We’ve covered that White has been a little bit more expansive of late, and we may have gotten a little foreshadowing in a moment or two against Brighton.

But you know what’s also clear from watching him after the break? He’s got his legs back.

At the 7-minute mark, he was already floating through the middle whenever Ødegaard wasn’t dropping, helping Ødegaard push up and rotate.

From there, an extra player wasn’t always necessary. So next, with the ball played backward and West Ham only having a few players forward, we see an interesting look: Raya is the “LCB,” Gabriel is on the right, Saliba is filling the right-back zone, and White is within the pivot. This is that good “positional” stuff, in which rigid position titles matter less than the thoughtful occupation of zones, and the coherent manipulation of space.

I hereby dub this pivot “White Rice.”

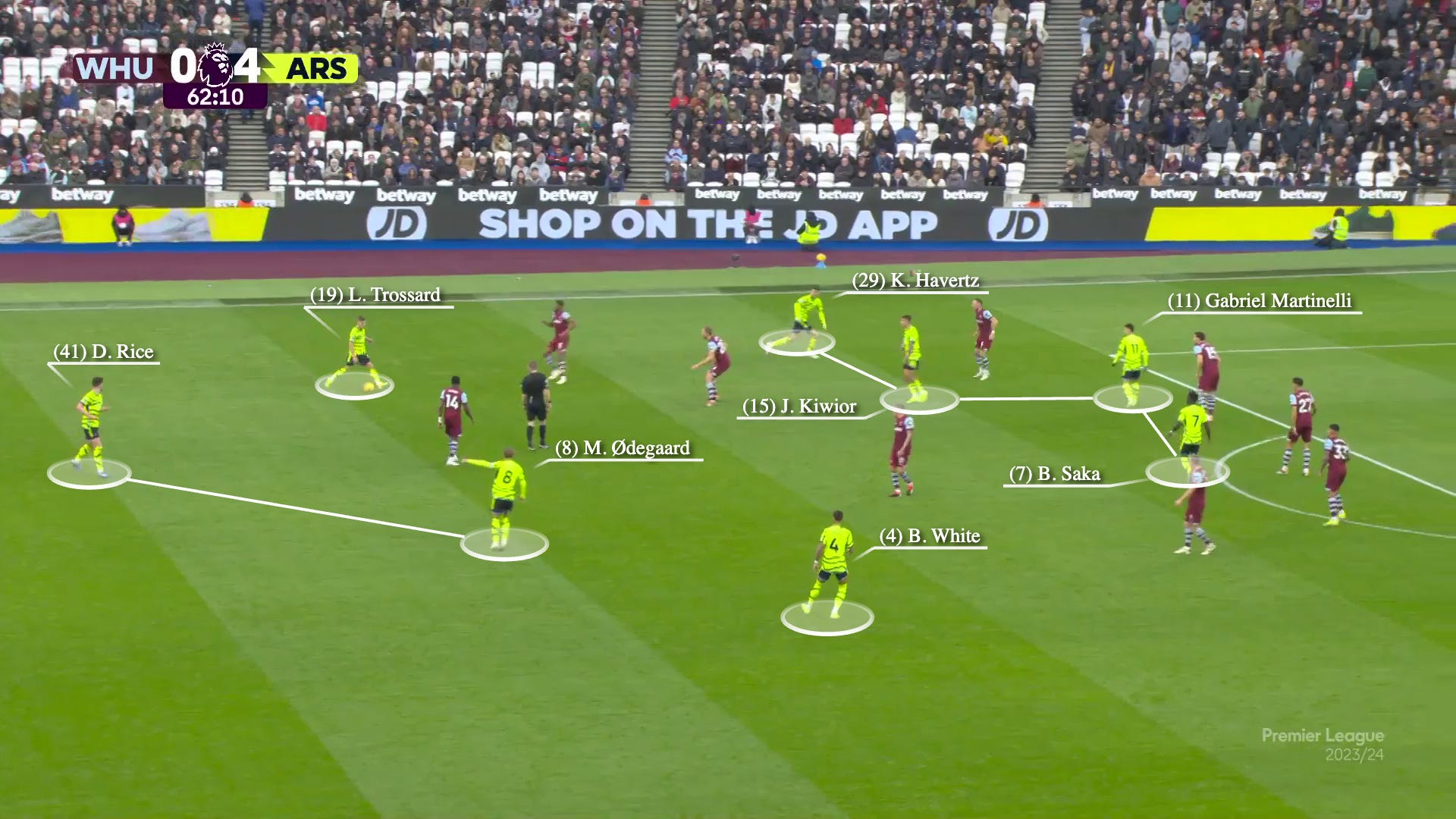

Especially after the goals were put on the board, things started getting more freewheeling.

There wasn’t adequate pressure on this next moment, so neither Ødegaard nor White dropped into the pivot with Rice. Havertz saw that and dropped to provide a fall-back option, but Rice was able to drill it down the touchline to White and kick off an interesting attack — again, with Saka in the half-space.

And crucially, when White did help out in the midfield, it didn’t automatically mean that Ødegaard would park in the right half-space like the old, static days.

Below, you can see that. White goes inside, so Ødegaard swings to that zone where White may usually be. Ødegaard does the “White roller” to get Saka into the central areas. Ødegaard is the one passing it, so he isn’t up there to potentially crowd things up. Things feel more threatening.

All of this combined into some of the most domineering attacking play from Arsenal you’ve seen this year.

💣 Devil’s advocate

Just as we didn’t want to be too results-driven when things were good, we don’t want a big win to stop us from looking at things critically.

This isn’t a structure for every opponent, nor should it be. There are a few things to watch out for in a set-up like this.

1. The sustainability of the “ask.”

Not only has Ødegaard been stacking some of the highest-passing games of his career, he’s been doing it low — dropping to receive directly from the centre-backs. From there, he goes up top to direct one of the highest-intensity presses in the world, running the most on the team. It’s worth considering whether this is a reasonable ask game after game. This is one of the reasons it’s important to have multiple looks. The Rice/Jorginho pivot is less of a burden for Ødegaard.

2. Whether certain yappy pressers can hassle White in the midfield.

It wasn’t too long ago that the only cover for Thomas Partey was Albert Sambi Lokonga and Mohamed Elneny. During those times, I went back and watched the midfield tape on all of our players to gauge the emergency options. I was most impressed with that of Ben White.

Here’s him playing midfield, intercepting KDB, and hitting it out to Trossard on the wing. For your records.

That said, he can feel a little “blocky” in some of those positions. Twisting and turning may be an overrated attribute in a midfielder — simple judgment, positioning, and passing ability go a long way — but I’d still have questions about whether somebody like Conor Gallagher could poke at him in these spots. I wouldn’t expect him to lose the ball much because he’s great at using his body, but it may turn him more conservative.

Once the play is in front of him, though, we’d be able to see some of his more expansive passing bag.

3. Growing pains and “over-fluidity.”

When you are using incredibly modular pivots and have players floating all over the pitch, there are a lot of relationships being built on the fly, and a lot for them to keep track of.

In many ways, the gameplan that this reminded me of most was Luton, which had the most fluid play of the year. Exhibit A:

Exhibit B:

Here’s what we said after that one about Kiwior:

Because of all of these complex and never-ending rotations, he was a little hesitant when his teammates had the ball, trying to understand his place in the washing machine. This means that once he actually got it, he had less space. He was also a press trigger.

That showed up again early.

But it didn’t really show up much after that. Kiwior was generally good, and a lot of this was due to a simplified portfolio of responsibilities. He wasn’t floating inside in the first phase.

Before the Rice blast that made it 6:0, I saw him snooping up top, looking for a back-post ball. It’s nice to see his confidence growing.

From there, there is a reason that these “over-fluid” build-ups aren’t the default, despite how fun they are and how much vibrant attacking play they can lead to.

For one, there can be a lot of redundant runs: players arriving into spots at the same time and giving the defenders an easier mark. I thought things were a little herky-jerky for a while, and that may have persisted if some set piece goals didn’t flow in. Game-state Rules Everything Around Me.

Moreover, because players are often transitioning between zones, or picking up the ball in places they don’t always do it in, there is a higher risk of a dangerous ball loss. We saw that when Martinelli dropped into the midfield to receive here.

Gabriel and Saliba swept it up, of course. Which brings us to the next part.

4. Changes to a tried-and-true backline setup.

Centre-back pairings are a lot like midfield pairings. You want complementary profiles. Saliba and Gabriel have worked so well not just because they’re big and good and general, but because of the subtleties of the roles they take up.

Saliba is one of the game’s best “central” centre-backs, and Gabriel is one of the game’s best “wide” centre-backs. They come in all shapes and sizes.

In a central profile, you generally want somebody calm, unbothered, strong, who can run to both sides, and who can dictate play with 100+ touches if needed.

In a wide profile, you’d like a 1v1 dominator — somebody who steps up and stops attacks before they begin, who is aggressive, and who leans into a challenge.

There are overlaps between the two, but the main delineation is temperament.

Gabriel puts on a weekly clinic in wide 1v1 defending as a centre-back. Below is him doing everything right against Mbeumo: stepping up to crowd space, delaying first, going “side-on” and getting a good angle, staying on the balls of his feet, taking quick steps, gradually crowding space, and only stepping in when there is a long touch. I get cranky when “technicality” is equated with “cool flick passes” — I think this shit is highly, highly technical. The body doesn’t naturally do this all. It’s learned.

When inversion comes to the right, though, this would place the LCB (Gabriel) into the middle of a three while the right-back ventures up the pitch. This was demoed a bit last year, in the preseason, and in some more throwaway games this year (like late against PSV), and the results have been mixed. Gabriel has looked a little sensitive to angles back there, and has had a few outright whiffs on high balls, which would be uncharacteristic in his normal spot.

It’s not only because of Gabriel. Saliba is good as a wide-CB, but it may not showcase his truly special abilities. He may also share a specific issue with White: tracking and disrupting 1-2 through-balls, and that tends to happen more when he’s out wide.

There may have been some behind-the-scenes stuff at play, who knows, but I think this offered an explanation as to why Gabriel didn’t make the starting XI in the early weeks when inversion was coming from the right-back. With Partey inverting, White started at RCB and Saliba started at LCB so that the latter could remain the “CCB” in a back-three.

Like so:

Alas, we saw the return of Gabriel at CCB against West Ham.

I watched back, and he was taking up these spots from the start. In typical games, the below screenshot may show Zinchenko floating up and a back-three of White, Saliba, and Gabriel — but here you get a different look, with Gabriel in the middle, holding the line against Bowen.

Those issues I was talking about with them switching roles? They didn’t really show up on Sunday. There were two of those 1-2 through-balls against White and Saliba, but Gabriel looked steady, calm, and imposing.

Part of this was due to the loneliness of the Moyes attack. Jarrod Bowen was sent up by himself, and the poor guy had to deal with the Bash Brothers.

But part of it is this: Gabriel is playing older, steadier, more mature. Maybe I shouldn’t write off this back-three configuration so quickly after all.

📈 The benefits to this all

So those are the trade-offs. Let’s get the benefits.

The value of this all was best encapsulated in the fifth (fifth!) goal, which we’ll walk through step-by-step. After a ‘crunch’ on the left side, Martinelli carried down as the team unfurled into position. These cross-zonal Martinelli dribbles usually foreshadow something good. He plays it to Rice as the team spreads out.

Rice and Ødegaard become the pivot as the play switches, and Martinelli floats above them. This position was used to great effect in this game.

Now that play has switched, Saka receives low and on the move. He started doing this a lot more in the Palace game, and it’s a great way of dragging left-backs around, and then arriving in interesting ways. Salah does this — he gets fewer high touches than our tandem, but more touches down the pitch. You’ll also see some of the slight clumsiness in this kind of build-up, with players running into similar zones and duplicating runs.

Now, with the play in the advanced area, you are not seeing the totally standard Arsenal look. Trossard has dropped low to receive, Kiwior is in the half-space, Havertz is doing a run in behind, and Saka is in the striker role. It’s a lot more for the opponent to understand and track.

Once the ball makes it back over to Ødegaard, Saka floats from the #9 into the half-space, isolates himself on Aguerd, and it’s 5-0.

So there you saw it all working in unison: flexible movement from Martinelli; lower positioning by Ødegaard; lower reception by Saka; interesting arrivals into the attacking third; then, Saka alone in the half-space for a goal.

Especially in the second half, the build-up could turn into a three-box-three, similar to what we saw against Liverpool — but with White pushing higher, somebody in the central area as a striker (it was Trossard here), and everybody arriving forward. When we saw too few players within the block in the early months, it was packed here. This “feels” like a good, durable way of beating up a mid-block to me.

There’s another advantage to the particular setup we saw on Sunday.

⚽️ Billy on the ball

If you watched Saliba at all in France, you’ll know that there is a part of his game that is currently holstered: carrying and bursting forward.

The numbers back this up. Look, I pulled them!

For Marseille, this wasn’t always complicated. With Peres (I think?) being the deep-CB in this clip, you can see how Saliba can just power-carry forward and obtain free progression for his side.

Against West Ham, you’ll see a similar thing here, with Gabriel fanning backward to support depth and Saliba pushing forward.

What was more unique was to see this in an even, early game-state: carrying, dribbling, pushing forward like a midfielder.

Because he’s good at this, it offers the same benefit we’ve been discussing earlier: the opportunity for players to arrive in the attacking third in interesting, unexpected ways that will unsettle a block.

Do the benefits outweigh the risks? You decide.

🥅 Passing, the frontline, and Trossard

Another evolution seems to be happening in this area.

Arsenal were previously more likely to keep two options on this line of build-up, with more players pushing and testing the back-line, or playing deep. Now more players are squeezing in here to provide options for central line-cutters and give opposing midfielders more to think about. This space was especially available to Trossard, Havertz, and Martinelli to exploit. Let’s see how it turned out.

Here’s Ødegaard dropping deep and looking every bit the lone-6 😜. With Martinelli, Havertz, and Trossard all overloading this zone, a lane opens up and Ødegaard hits it.

Here’s Havertz dropping in to do the same. Again, it’s Ødegaard.

This area proved to be a fruitful place for Trossard to drop. He is proof that talents are nuanced; he can have trouble with pressers back here if he’s asked to deliver more straightforward back passes with the appropriate weight. But if he’s able to drop and face the play, he’s sublime.

Here’s one of those. Look how Trossard drops, Havertz sees that Martinelli is isolated, so he bends his run to drag the CB and get Martinelli some more space. Especially on rewatch, you’ll notice how many interlocking motions Arsenal run.

And here’s the one we all remember. Arsenal weren’t pinning with a lot of players, so West Ham pushed up a bit and Saka responded with a darting run, and Trossard made them pay.

Crucially, this all enabled Martinelli to dribble across zones, rotate into striker, poke the back-line, and play his expressive best. If I had to draw up a “received passes” map for him, it would look a lot like this.

All of this winding and freelancing led to opportunities like this, where Martinelli did a byline cut on the right side, and Havertz and Trossard were both free.

You can also see this in the passmap of Havertz — which doesn’t look like a poacher hanging out in the left channel.

My last compliment to the passing was that the crosses were more immediate and purposeful. The team notched the highest number of crosses into the penalty area since the last time against West Ham.

One of those crosses was this one by Kiwior.

If you’ve been reading for long, you’ll know one of my personal conquests: if you’re going to play a lanky shadow striker at left-8, then you should kick balls to him like he’s a lanky shadow striker at left-8. That largely happened here; the specific opportunities were just well-defended.

OK, let’s wrap ‘er up.

🔥 Final thoughts on build-up

Before the break, there was a truly disappointing (and awfully frustrating) run of results, culminating in a 2-1 loss at Craven Cottage. At that point, I wrote What Ails Arsenal, a piece I took a long time to formulate, and that I’m proud of.

At the end of that one, I offered a few thoughts on how to improve in the coming months. Among them:

xG and luck should naturally improve, says the hopeful idiot.

Saka must take advantage of the semi-vacated half-space. He needs to learn from Salah in respect: the sheer immediacy of some of his actions. More first-touch shots and snap crosses, please.

With Martinelli, I’d look to have him get fewer touches, drive in a few less crosses, and get a lot more shots off. Ødegaard’s freedom helps here too; he can hit Martinelli himself. In the final third, I like him freelancing around, becoming ungovernable, and especially attacking the soft spot in the middle of the box on a cutback cross.

Getting the wingers the ball a little bit quicker, and having them act a little more decisively, is an obvious key to things. A less-obvious thing is increasing the amount of times they’re interplaying with one another directly.

In the next piece — Back in Action — I went a step further and wrote a “tactical wishlist” for the games after the restart. Here was what I hoped to see:

1. Bid farewell to noble experiments

Generally speaking, there are two tactical setups that I’d probably say farewell to for the rest of the season: Kiwior as a full midfield pivot, and Havertz as a full midfield pivot.

2. More complementary pods

Facing Lowest Blocks: Rice (lone 6) / Havertz and others (left-8) / Ødegaard (dropping) / Jesus or Trossard (False-9)

Default + Facing More Evenly-Matched Teams We Seek to Press: Rice (6/8) / Jorginho/Partey (6/8) / Ødegaard (floating #10) / Whoever (9)

In Highest-Difficulty Away Games (i.e. Man City, UCL): Jorginho/Partey (6) / Rice (left-8) / Ødegaard (#10) in a compact, mid-block / Havertz (9)

3. Real chances for real talents

Particularly ESR and Vieira.

4. Platform the biggest strengths of the players

Martinelli: With some of the dynamics elsewhere improved, a lot more hopeful transition balls should get hit to Martinelli (and he should cheat more), and he should crash that central area of the box with more regularity for cut-backs and crosses.

Havertz: Way more far-post crosses to him, please.

Rice: Especially in this “double-6” formation where he’s more likely to be covered by a midfield partner, he should unsettle blocks through central carries with a lot more frequency.

White: Should have a more expansive passing range.

5. Faster switches

Self explanatory.

Looking pretty good.

In actuality, I believe Arsenal have been headed in the right direction since December, results be damned. While it’s easy to overstate the most recent tactical permutations, I think the team has been on a journey of finding the set-ups that really have teeth. When they did, they fell prey to some bad finishing and bad luck. Now, they’ve got a little rest, some kinder variance, and some finishing boots.

Throughout, the role of Ødegaard can’t be overstated.

Here are some final thoughts on the build-up structure we saw against West Ham:

The deepest interplay was a little clunky in the early stages, and may have remained so if not for some goals being put on the board.

However, it was interesting and promising, particularly the idea of overloading the zones above the double-pivot. From there, the attackers were able to arrive in interesting ways, which helped unsettle defenders and create lanes in the block.

For that reason, I think this fluid build-up against low-blocks is generally worth the risk.

Inverting Ben White may just be a fallback in case Zinchenko is unavailable again, but it looks preferable to inverting Kiwior in my eyes. Now that White’s legs are back, we may see this take some interesting turns.

I’ve had plenty of issues with the “complementary dynamics” of the frontline attackers, and whether the lineup selections help them all shine. On both counts, I think this was a 10/10.

The preferable set-up in games like this is probably still Zinchenko and Ødegaard “splitting the pivot,” which should help the left side get the ball with more urgency as well.

Now, for some nonsense.

✌️Spare, closing thoughts

Before free-kicks, you may notice Gabriel strolling over to the taker to convey the battle plan. Here he is delivering a message to Declan Rice.

And here was the result.

Recently, the team site did an interview with Rice where they asked who he was closest to on the team. His first response was Gabriel, saying they “get along so, so well.” I was thinking about that during this clip.

Next, you’ll get a brief rant from me on “average positioning” and pass maps. Here was the average positioning against West Ham:

As you’ll see in the above, Saka is “isolated.” This is also how Martinelli looks in the Champions League average positioning. What’s the common denominator? Saka fucking ate in this one, and Martinelli has been used perfectly in the UCL.

This is a long way of saying that these charts show something, but it’s not always what people expect — it’s not necessarily indicative of functional spacing or relationships on the pitch. If a player is switching between left-wing and striker, for example, they may be seen as “crowding the space” of another player on the front-line.

In reality, it’s just one point of data, and should be discussed as such.

Finally:

I was going to try and fit in a brief Nwaneri profile into this but that feels like a full post. He is a fascinating player and I’ll keep preaching the gospel of patience and reasonable expectation with everybody else, but likely fail on my end.

The bench options were rough in this one: no ESR, Jesus, Tomiyasu, Partey, Timber, Vieira, or Zinchenko. Arsenal can do some real things this year but the biggest looming counterargument is probably functional depth.

I didn’t talk much about out-of-possession stuff in this one, but Arsenal now have 48 high turnovers resulting in a shot, leading the league. They have 16 more than Man City, for example. They are generating these opportunities but not necessarily finishing them; Bournemouth has 14 fewer turnovers resulting in a shot, for example, but four more goals.

Havertz vs Souček is one of those low-key, seemingly low-stakes matchups that managers watch intently — because it becomes a question of second balls, physicality, and duels. Havertz won. For the record, Havertz can play as both a high midfielder and as a striker. He's just been best at the former with a 9 who drops/rotates and with Ødegaard helping in build-up. Every player is dependent on surrounding dynamics like that to some degree. Players don't have to be One Thing.

On that note, the big guy ratio is so important against a team like West Ham. If you have too few, a short king is getting isolated by the opponent on corners. If it’s good, it’s much easier to find an advantage: with Kiwior at left-back, Havertz at left-8, and all the normal biggies behind that, there was a “cumulative” push that resulted in set piece goals. Which reminds me that I’ve under-discussed set pieces here. Go read Jake Fox.

And here’s a final ode to Saka. When told he had crossed the 50-goal marker, he said this: “To be honest, I’m really happy to achieve that, but I’m not sure I can be happy today. I missed some chances that I thought I could have scored, you know, but obviously it’s a great achievement, so I’m proud of that.” He scored two goals. Something, something, mentality monster. I saw some conversations going around about who Arsenal’s best player is. My opinion? It’s him.

Back at it tomorrow.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this.

In conclusion:

Be good, and do forward this email. ❤️

Billy you need to be monetising this gold you’re spinning

Brilliant post, so clearly articulated with in-game clips to support, totally psyches me up for upcoming games. I learn so much from you 🙏